Abstract

Background

Traction has been used to treat low‐back pain (LBP), often in combination with other treatments. We included both manual and machine‐delivered traction in this review. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 1995, and previously updated in 2006.

Objectives

To assess the effects of traction compared to placebo, sham traction, reference treatments and no treatment in people with LBP.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Back Review Group Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2012, Issue 8), MEDLINE (January 2006 to August 2012), EMBASE (January 2006 to August 2012), CINAHL (January 2006 to August 2012), and reference lists of articles and personal files. The review authors are not aware of any important new randomized controlled trial (RCTs) on this topic since the date of the last search.

Selection criteria

RCTs involving traction to treat acute (less than four weeks' duration), subacute (four to 12 weeks' duration) or chronic (more than 12 weeks' duration) non‐specific LBP with or without sciatica.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed study selection, risk of bias assessment and data extraction. As there were insufficient data for statistical pooling, we performed a descriptive analysis. We did not find any case series that identified adverse effects, therefore we evaluated adverse effects that were reported in the included studies.

Main results

We included 32 RCTs involving 2762 participants in this review. We considered 16 trials, representing 57% of all participants, to have a low risk of bias based on the Cochrane Back Review Group's 'Risk of bias' tool.

For people with mixed symptom patterns (acute, subacute and chronic LBP with and without sciatica), there was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that traction may make little or no difference in pain intensity, functional status, global improvement or return to work when compared to placebo, sham traction or no treatment. Similarly, when comparing the combination of physiotherapy plus traction with physiotherapy alone or when comparing traction with other treatments, there was very‐low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that traction may make little or no difference in pain intensity, functional status or global improvement.

For people with LBP with sciatica and acute, subacute or chronic pain, there was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that traction probably has no impact on pain intensity, functional status or global improvement. This was true when traction was compared with controls and other treatments, as well as when the combination of traction plus physiotherapy was compared with physiotherapy alone. No studies reported the effect of traction on return to work.

For chronic LBP without sciatica, there was moderate‐quality evidence that traction probably makes little or no difference in pain intensity when compared with sham treatment. No studies reported on the effect of traction on functional status, global improvement or return to work.

Adverse effects were reported in seven of the 32 studies. These included increased pain, aggravation of neurological signs and subsequent surgery. Four studies reported that there were no adverse effects. The remaining studies did not mention adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

These findings indicate that traction, either alone or in combination with other treatments, has little or no impact on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work among people with LBP. There is only limited‐quality evidence from studies with small sample sizes and moderate to high risk of bias. The effects shown by these studies are small and are not clinically relevant.

Implications for practice To date, the use of traction as treatment for non‐specific LBP cannot be motivated by the best available evidence. These conclusions are applicable to both manual and mechanical traction.

Implications for research Only new, large, high‐quality studies may change the point estimate and its accuracy, but it should be noted that such change may not necessarily favour traction. Therefore, little priority should be given to new studies on the effect of traction treatment alone or as part of a package.

Keywords: Humans, Traction, Traction/adverse effects, Acute Pain, Acute Pain/therapy, Chronic Pain, Chronic Pain/therapy, Low Back Pain, Low Back Pain/complications, Low Back Pain/therapy, Pain Measurement, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Sciatica, Sciatica/complications, Sciatica/therapy

Plain language summary

Traction for low‐back pain

We reviewed the evidence on the effect of traction on pain intensity, ability to perform normal daily activities, overall improvement and return to work among people with low back pain (LBP) in the acute (less than four weeks' duration), subacute (from four to 12 weeks' duration) or chronic (more than 12 weeks' duration) phase. Some patients also had sciatica. We examined the effects of traction immediately after the traction session, in the short‐term (up to three months after traction) and in the long‐term (around one year after traction).

LBP is a major health problem around the world and is a major cause of medical expenses, absenteeism and disability. One treatment option for LBP that has been used for thousands of years is traction, the application of a force that draws two adjacent bones apart from each other in order to increase their shared joint space. Various types of traction are used, often in combination with other treatments. The most commonly used traction techniques are mechanical or motorized traction (where the traction is exerted by a motorized pulley) and manual traction (in which the traction is exerted by the therapist, using his or her body weight to alter the force and direction of the pull).

The evidence is current to August 2012. The review included 32 studies and 2762 people with LBP. Most studies included a similar population of people with LBP with and without sciatica. The majority of studies included people with acute, subacute and chronic LBP. Most studies reported follow‐up of one to 16 weeks, and a limited number of studies reported long‐term follow‐up of six months to one year.

The included studies show that traction as a single treatment or in combination with physiotherapy is no more effective in treating LBP than sham (pretend) treatment, physiotherapy without traction or other treatment methods including exercise, laser, ultrasound and corsets. These conclusions are valid for people with and without sciatica. There was no difference regarding the type of traction (manual or mechanical).

Side effects were reported in seven of the 32 studies and included increased pain, aggravation of neurological signs and subsequent surgery. Four studies reported that there were no side effects. The remaining studies did not mention side effects.

The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate. There was a scarcity of high‐quality studies, especially those that distinguished between people with different symptom patterns (with and without sciatica, with pain of different duration).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Traction compared with placebo, sham or no treatment for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica.

| Traction compared with placebo, sham or no treatment for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica | |||

|

Patient or population: people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica Settings: diverse Intervention: traction Comparison: placebo, sham or no treatment | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain intensity VAS (0‐100 mm). Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

1 trial showed that there was no difference in pain intensity between the 2 groups (MD ‐4, 95% CI ‐17.7 to 9.7). | 60 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝

moderate Imprecision (< 400 participants) |

|

Functional status Oswestry Disability Index or Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

|

Global improvement Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

1 trial showed that there was no difference in global improvement between the 2 groups (RD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.28). | 81 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝

moderate Imprecision (< 300 participants) |

|

Return to work Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

| Adverse effects | 1 trial reported aggravation of neurological signs in 28% of the traction group, 20% of the light traction group and 20% of the placebo group. | ||

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RD: risk difference; VAS: visual analogue scale. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Note. Each 'Summary of findings' table presents evidence for a specific comparison and a set of prespecified outcomes. Therefore, the information presented in the tables is limited by the comparisons and outcomes reported in the included studies.

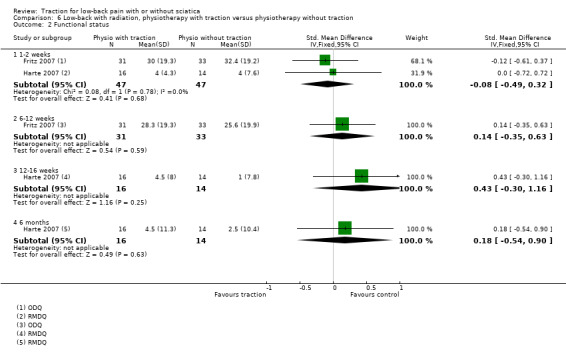

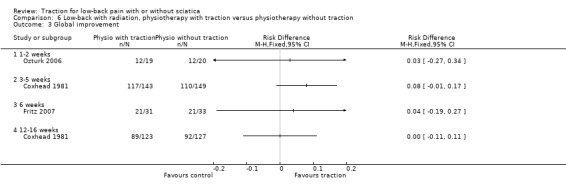

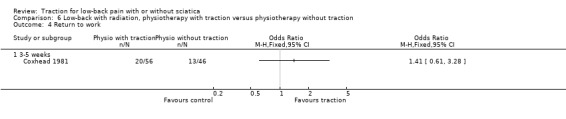

Summary of findings 2. Physiotherapy with traction compared with physiotherapy without traction for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica.

| Physiotherapy with traction compared with physiotherapy without traction for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica | |||

|

Patient or population: people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica Settings: physical medicine and rehabilitation outpatient clinic of a larger hospital Intervention: physiotherapy with traction Comparison: physiotherapy without traction | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain intensity VAS (0‐100 mm). Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

1 trial showed that there was no difference in pain intensity between the 2 groups (MD 5, 95% CI ‐5.7 to 15.7) in favour of the control group. | 39 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Study design (high risk of bias) Imprecision (< 400 participants) |

|

Functional status Oswestry Disability Index or Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

2 trials showed that there was no difference in functional status between the 2 groups (SMD from 0.36 (95% CI ‐0.27 to 1.00) to 0.43 (95% CI ‐0.30 to 1.16)). | 69 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Study design (high risk of bias) Imprecision (< 400 participants) |

|

Global improvement Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

1 trial showed no difference in global improvement, another trial did show a clinically significant difference in global improvement (RD 0.53, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.79). | 220 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Study design (high risk of bias) Imprecision (< 300 participants) |

|

Return to work Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

| Adverse effects | 1 study reported that 25% of the physiotherapy with traction group and 37% of the physiotherapy without traction group felt worse at 3 months' follow‐up. | ||

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RD: risk difference. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Summary of findings 3. Traction compared with another type of traction for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica.

| Traction compared with another type of traction for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica | |||

|

Patient or population: people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica Settings: diverse Intervention: traction Comparison: another type of traction | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain intensity VAS (0‐100 mm). Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

|

Functional status Oswestry Disability Index or Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

|

Global improvement Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

|

Return to work Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

| Adverse effects | 1 trial reported increased pain in 31% of the static traction group and 15% of the intermittent traction group. | ||

| VAS: visual analogue scale. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Summary of findings 4. Traction compared with any other treatment for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica.

| Traction compared with any other treatment for people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica | |||

|

Patient or population: people with low‐back pain with and without sciatica Settings: diverse Intervention: traction Comparison: other treatment | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain intensity VAS (0‐100 mm). Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

3 trials, of which 1 compared traction with 2 other types of treatment, showed no difference greater than 5 points on the VAS scale between the 2 groups (MD ‐2.90 (95% CI ‐8.53 to 2.93) to 4.50 (95% CI ‐0.45 to 9.45). | 304 (3) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝

moderate Imprecision (< 400 participants) |

|

Functional status Oswestry Disability Index or Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

3 trials, of which 1 compared traction to 2 other types of treatment and used 2 types of questionnaires to assess functional status, showed no difference between the 2 groups (SMD ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.23) to 0.51 (95% CI ‐0.12 to 1.14)). | 350 (3) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝

moderate Imprecision (< 400 participants) |

|

Global improvement Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

1 trial showed no difference in global improvement (RD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.1 to 0.2). | 42 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝

low Study design (high risk of bias) Imprecision (< 300 participants) |

|

Return to work Follow‐up 12‐16 weeks. |

Not measured. | ||

| Adverse effects | 1 trial reported temporary deterioration of low‐back pain in 17% of the traction group and 15% of the exercise group. | ||

| MD: mean difference; RD: risk difference; SMD: standardized mean difference. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Background

Description of the condition

Low‐back pain (LBP) is a major health problem around the world and a major cause of medical expenses, absenteeism and disability (Dagenais 2008; Lambeek 2011; Vos 2012). Although LBP is usually a self limiting and benign condition that tends to improve spontaneously over time, a large variety of therapeutic interventions is available for treatment (Chou 2007). Sciatica can result when the nerve roots in the lower spine are irritated or compressed. Most often, sciatica is caused when the L5 or S1 nerve root in the lower spine is irritated by a herniated disc. Degenerative disc disease may irritate the nerve root and cause sciatica, as can mechanical compression of the sciatic nerve, such as from spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis or arthritis in the spine. For the purposes of this review, we define sciatica as pain radiating down the leg(s) along the distribution of the sciatic nerve (which is usually related to mechanical pressure, inflammation of lumbosacral nerve roots or both) (Bigos 1994).

Description of the intervention

One treatment for LBP and sciatica is traction, which has been used for thousands of years. It is used relatively frequently in North America (e.g. up to 30% of people with acute LBP and sciatica in Ontario, Canada) (Li 2001), and to a lesser extent in the UK, Ireland and the Netherlands (Harte 2005). Traction is often provided in combination with other treatment modalities (Harte 2005). The most commonly used traction techniques are mechanical or motorized traction (where the traction is exerted by a motorized pulley), manual traction (in which the traction is exerted by the therapist, using his or her body weight to alter the force and direction of the pull), and auto‐traction (where the person controls the traction forces by grasping and pulling bars at the head of the traction table). There are also less common forms, such as underwater (where the person is fixed perpendicularly in a deep pool, a bar is grasped under the arms and traction is applied), and gravitational traction (e.g. bed rest traction, in which the person is fixed to a tilted table or bed, and inverted traction, where the participant is held in an inverted position by the ankles and another part of the lower extremities and gravity provides the force).

Lumbar traction uses a harness (with Velcro strapping) that is fitted around the lower rib cage and around the iliac crest. Duration and level of force exerted through this harness can be varied in a continuous or intermittent mode. The force can be standardized only in motorized traction or in methods using computer technology. With other techniques, total body weight and the strength of the person or therapist determine the forces exerted. In the application of traction force, consideration must be given to counter forces such as lumbar muscle tension, lumbar skin stretch and abdominal pressure, which depend on the participant's physical constitution. If the person is lying on the traction table, the friction of the body on the table or bed provides the main counter force during traction.

How the intervention might work

The exact mechanism through which traction might be effective is unclear. It has been suggested that spinal elongation, by decreasing lordosis and increasing intervertebral space, inhibits nociceptive impulses, improves mobility, decreases mechanical stress, reduces muscle spasm or spinal nerve root compression (due to osteophytes), releases luxation of a disc or capsule from the zygo‐apophysial joint, and releases adhesions around the zygo‐apophysial joint and the annulus fibrosus.

A more recent rationale, adapted to available neurophysiological research, suggests that stimulation of proprioceptive receptors in the vertebral ligaments and in the mono segmental muscles may modify and halt what is being conceptualized as a 'dysfunction'. Dysfunction is a relatively generalized disturbance involving higher cerebral centres as well as peripheral structures for postural control. The dysfunction involves self maintaining pain‐provoking neuromuscular reflex patterns. In relation to benefits of traction, this rationale involves the 'shocking' of dysfunctional higher centres by means of relaying 'unphysiological' proprioceptive information centrally, and thus 'resetting' the dysfunction (Blomberg 2005). So far, none of the proposed mechanisms has been supported by sufficient empirical information.

Little is known about the adverse effects of traction. Only a few case reports are available, which suggest that there is some danger for nerve impingement in heavy traction (i.e. lumbar traction forces exceeding 50% of the total body weight). Other risks described for lumbar traction are respiratory constraints due to the traction harness or increased blood pressure during inverted positional traction. There is some debate about the effect of low traction forces. Beurskens 1997 says that a certain amount of force is required to achieve separation of the vertebra and widening of the intervertebral foramina. Forces below 20% of the participants' body weight do not achieve this goal and, therefore, can be considered to constitute a placebo or sham traction. Other reports say that these forces can still be expected to produce positive results, as even low traction forces can produce intervertebral separation due to flattening of lumbar lordosis, and relaxation of spinal muscles (Harte 2003; Krause 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review updates our previous Cochrane review (Clarke 2006a). The 2006 review included 25 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and was an update of a previous review of the effectiveness of traction for back and neck pain (Van der Heijden 1995). The previous review stated that traction was not likely to be effective for people with and without sciatica, due to inconsistent results and methodological problems in most studies. This update integrated new literature on the subject and was performed using the latest methods.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to determine if traction was more effective than reference treatments, placebo, sham traction or no treatment for LBP with or without sciatica, with a focus on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only RCTs.

Types of participants

We included RCTs involving the following types of participants: male or female; aged 18 years or older; treated for LBP; in the acute, subacute or chronic phases, with or without sciatica. We excluded studies involving people with LBP due to specific causes (e.g. tumour, metastasis, fracture, inflammation, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis).

Types of interventions

We included RCTs using any type of traction, such as mechanical traction, manual traction (unspecific or segmental traction), computerized traction, auto‐traction, underwater traction, bed rest traction, inverted traction, continuous traction and intermittent traction. Additional treatment was allowed, provided that traction was the main contrast between the intervention and control groups. We included studies with any type of control group (i.e. those that used placebo, sham, no treatment or other treatments).

Types of outcome measures

The four primary outcome measures that we considered to be the most important were pain intensity (e.g. measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS) or a numerical rating scale (NRS)), back‐pain‐specific functional status (e.g. measured by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)), a global measure of improvement (e.g. overall improvement, proportion of participants recovered, subjective improvement of symptoms) and return to work (e.g. measured by return to work status or days off work). We also considered reported adverse effects.

These outcomes could be measured immediately after the end of one traction session, immediately after a course of traction sessions, in the short‐term after the end of the traction sessions (up to three months), or in the long‐term (around one year).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used the results of the literature search listed in Appendix 1, updating the three previous versions of this review (Clarke 2006a; Clarke 2006b; Van der Heijden 1995a). This included a computer‐aided search the Cochrane Back Review Group Specialized Register (August 2012), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2012 Issue 8), MEDLINE (January 2006 to August 2012), EMBASE (January 2006 to August 2012) and CINAHL (January 2006 to August 2012).

Searching other resources

Furthermore, we screened reference lists of relevant reviews and identified RCTs, as well as references in personal files of the review authors.

Data collection and analysis

In this review, we followed the guidelines of the Cochrane Back Review Group (Furlan 2009), and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently selected the trials to be included in the systematic review using title, abstract and keywords. The same two review authors independently applied the selection criteria to the studies that were retrieved by our literature search. We used consensus to resolve disagreements concerning selection and inclusion of RCTs. There was the option to consult a third review author if disagreement had persisted, although this was not necessary. We only evaluated full papers and excluded papers written in languages other than English, Dutch, German, French and Swedish.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (IW and ISW) independently extracted the data (using a standardized form) considering the study population (e.g. number of participants, age, gender, type and duration of back pain), the interventions (type, intensity, and frequency of index and reference interventions) and the primary outcomes (type and duration of follow‐up). We used consensus to resolve disagreements and we would have consulted a third review author (GH) if disagreement persisted, although this was not necessary. We summarized key findings in a narrative format. We did not blind data extraction.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane Back Review Group's 'Risk of bias' tool to assess the risk of bias of the included RCTs (Furlan 2009). The 12 criteria are listed in Appendix 2. Studies included in the previous version of the review had not been assessed using this tool. Therefore, we re‐assessed these studies according to the updated methods. We could not obtain two articles (Lind 1974; Reust 1988) and two articles were written in a language that the review authors did not master (Bihaug 1978; Walker 1982). We transformed the previous risk of bias assessments of these four trials to the new format without re‐assessing them. As a result, supporting statements for the risk of bias assessments are missing for these studies. Two review authors (IW and ISW) independently assessed the methodological quality. Review authors resolved their initial discrepancies during discussion; the presented results are based on their full consensus. We did not blind quality assessment with regard to the authors, institution and journal. We did not contact study authors for additional information, because half the trials were published in the late 1990s. If the article did not contain the required information for the scoring of a specific item, we scored the item as 'unclear'.

We scored the criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk', and reported them in the 'Risk of bias' table. We defined a study with a low risk of bias as one fulfilling six or more of the criteria and having no fatal flaws. In the previous review, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which six was considered the cut‐off point for low risk of bias. A second sensitivity analysis was performed in which half of items that had been scored 'unclear' in each trial were included as 'positive'. The same cut‐off point of six for low risk of bias is supported by empirical evidence (Van Tulder 2009).

Blinding of participants and care providers to treatment allocation is nearly impossible in trials of traction therapy. Given that some of the primary outcomes assessed in this review are subjective measures (i.e. pain and functional status), any attempt to blind the outcome assessor regarding these outcomes can be considered irrelevant. However, most studies also assessed objective outcome measures. If the care provider assessing those outcomes was blinded, the item was scored as 'low risk'.

Measures of treatment effect

We analyzed dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk difference. We analyzed continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD) when the same instrument was used to measure outcomes, or the standardized mean difference (SMD) when different instruments were used to measure the outcomes. We converted VAS or NRS scales to a 100‐point scale. We expressed uncertainty using with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

We grouped outcomes by timing when they were measured: immediately after, short term and long term.

Unit of analysis issues

In several studies, we compared more than two intervention groups. We included these studies by making pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups with traction being one of the intervention groups. The same group of participants was included more than once in these examples (e.g. underwater traction versus underwater massage and underwater traction versus balneotherapy in the study performed by Konrad 1992). These participants were not counted twice in the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

In cases where data were reported as a median with an interquartile range (IQR), we assumed that the median was equivalent to the mean and the width of the IQR equivalent to 1.35 times the standard deviation in accordance with Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 7.7.3.5 (Higgins 2011). If standard deviations were not given, we calculated them from the 95% CIs, P values based on a two‐sided t‐test or standard errors. We did not include data reported in graphs in this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic; however, the decision regarding heterogeneity was dependent upon the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011). We defined substantial heterogeneity as an I2 greater than 50%, and where necessary, the effect of the interventions were synthesised narratively when the I2 statistic was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We searched ClinicalTrials.org and ISRCTN.org for the protocols of included studies. When protocols were available, we checked studies for selective outcome reporting.

Data synthesis

A quantitative analysis had been planned, but most of the studies did not provide sufficient data to enable statistical pooling (e.g. some trials reported the mean score but not the standard deviation, other trials reported median and IQR; some trials reported only post‐intervention means and other trials reported mean change scores; some trials did not report any numerical data. Therefore, we used a descriptive analysis to summarize the data. In this analysis, we used a rating system of levels of evidence to summarize the results of the studies in terms of the strength of the scientific evidence. To accomplish this, we used the GRADE approach, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and adapted in the updated Cochrane Back Review Group method guidelines (Furlan 2009). The system consists of five levels of evidence, based on performance against five principal domains or factors:

high‐quality evidence ‐ consistent findings among at least 75% of RCTs with low risk of bias, consistent, direct and precise data and no known or suspected publication biases. Further research is unlikely to change either the estimate or our confidence of the results;

moderate‐quality evidence ‐ one of the domains is not met. Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

low‐quality evidence ‐ two of the domains are not met. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate;

very‐low‐quality evidence ‐ three of the domains are not met. We are very uncertain about the results;

no evidence ‐ no RCTs were identified that addressed this outcome.

Factors that may decrease the quality of the evidence are: study design and risk of bias (downgraded when > 25% of the participants were from studies with a high risk of bias), inconsistency of results, indirectness (downgraded when > 50% of the participants were outside the target group), imprecision (downgraded when the total number of participants was less than 400 for continuous outcomes and 300 for dichotomous outcomes) and other factors (e.g. reporting bias).

Because the majority of studies contained a mix of participants with acute, subacute and chronic LBP, we did not separate out these groups in our analyses, other than in several trials involving only people with chronic LBP. We categorized studies as including people 'with sciatica' if more than66% of the participants were described as having sciatica (this may or may not have included those with nerve root symptoms) or if there was a separate analysis of outcomes in those with sciatica.

Clinical relevance

Two review authors independently carried out an analysis of the clinical relevance of each study. Without using an arbitrary predefined threshold, studies were judged as to whether: participants were described in enough detail to allow practitioners to decide whether they were similar to those in their practices; interventions and treatment settings were described well enough to allow practitioners to provide the same treatment for their participants; clinically relevant outcomes were measured and reported; the size of the effect; and the treatment benefits were worth the potential harms (see Table 5).

1. Clinical relevance.

| Author | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Effect size | Benefits/harms |

| Beurskens 1997 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bihaug 1978 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Borman 2003 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Coxhead 1981 | + | ‐ | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fritz 2007 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gudavalli 2006 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Güvenol 2000 | + | + | + | ? | ‐ |

| Harte 2007 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Konrad 1992 | + | ? | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Larsson 1980 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Letchuman 1993 | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Lidström 1970 | + | + | + | ? | ‐ |

| Lind 1974 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ljunggren 1984 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ljunggren 1992 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mathews 1975 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mathews 1988 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ozturk 2006 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Pal 1986 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Reust 1988 | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Schimmel 2009 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sherry 2001 | + | + | + | + | ? |

| Simmerman 2011 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sweetman 1993 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tesio 1993 | + | + | + | ? | ‐ |

| Unlu 2008 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Van der Heijden 1995 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Walker 1982 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 1973 | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 1984 (1) | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Weber 1984 (2) | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

| Werners 1999 | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ |

+: yes; ‐: no; ?: unknown.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Predefined subgroup analyses included:

different types of comparison (traction versus placebo, sham or no treatment; physiotherapy with traction versus physiotherapy without traction; different types of traction and traction versus other treatments);

different symptom patterns in subjects (mixed population of people with LBP with and without sciatica; people with LBP with sciatica and people with LBP without sciatica).

However, we were not able to conduct these analyses, because of reasons stated above. Instead, the results were synthesized narratively. 'Summary of findings' tables were generated for all analyses of different types of comparison. Primary outcome measures at a follow‐up duration of 12 to 16 weeks were included in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Sensitivity analysis

In the previous review, sensitivity analyses were carried out to determine the cut‐off for high‐quality studies. The cut‐off point was set at six criteria for risk of bias, which is supported by empirical evidence (Van Tulder 2009). We considered that studies that met six or more of the criteria for risk of bias carried low risk of bias, whereas studies that met fewer than six of the criteria carried high risk of bias. We did not plan or carry out any new sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

We identified 32 trials that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Seven new trials were published since the publication of the previous review (Fritz 2007; Gudavalli 2006; Harte 2007; Ozturk 2006; Schimmel 2009; Simmerman 2011; Unlu 2008). We included all 25 trials discussed in the previous review in this review. The total number of studies retrieved by all search methods over time was not available. In this review, we included 32 studies, involving 2762 participants. Two of these studies were reported in one publication (Weber 1984); in four of the studies, there was more than one pertinent publication (Beurskens 1997; Gudavalli 2006; Mathews 1988; Van der Heijden 1995).

Presence of sciatica

Twenty‐three of the studies included a relatively homogeneous population of people with LBP and sciatica (Bihaug 1978; Coxhead 1981; Fritz 2007; Güvenol 2000; Harte 2007; Larsson 1980; Lidström 1970; Lind 1974; Ljunggren 1984; Ljunggren 1992; Mathews 1975; Mathews 1988; Ozturk 2006; Pal 1986; Reust 1988; Sherry 2001; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Unlu 2008; Walker 1982; Weber 1973; two trials in Weber 1984). Eight studies included a greater mix of participants with and without sciatica (Beurskens 1997; Borman 2003; Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Letchuman 1993; Tesio 1993; Van der Heijden 1995; Werners 1999). There was only one study that exclusively involved people who did not have sciatica (Schimmel 2009).

Duration of low‐back pain

Ten studies included solely or primarily people with chronic LBP of more than 12 weeks (Borman 2003; Gudavalli 2006; Güvenol 2000; Ljunggren 1984; Schimmel 2009; Sherry 2001; Tesio 1993; Van der Heijden 1995; two in Weber 1984); in one study, participants were all in the subacute range (four to 12 weeks) (Konrad 1992); in 17 studies, the duration of LBP was a mixture of acute, subacute and chronic (Beurskens 1997; Bihaug 1978; Coxhead 1981; Fritz 2007; Harte 2007; Larsson 1980; Lidström 1970; Lind 1974; Ljunggren 1992; Mathews 1975; Mathews 1988; Ozturk 2006; Pal 1986; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Unlu 2008; Walker 1982); in five studies duration was not specified (Letchuman 1993; Reust 1988; Weber 1973; and two in Weber 1984).

Comparisons

Thirteen studies compared traction with sham traction (Beurskens 1997; Letchuman 1993; Mathews 1975; Pal 1986; Reust 1988; Schimmel 2009; Van der Heijden 1995; Walker 1982; Weber 1973; and two in Weber 1984), with some kind of placebo (sham shortwave diathermy, Sweetman 1993; sham shortwave Lind 1974); or with no treatment (Konrad 1992). Fifteen studies compared traction with other treatments (Bihaug 1978; Coxhead 1981; Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Larsson 1980; Lidström 1970; Lind 1974; Ljunggren 1992; Mathews 1988; Sherry 2001; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Unlu 2008; Werners 1999; Weber 1984). In one of these (Lind 1974), auto‐traction was compared with physiotherapy, in which Tru‐Trac traction was one of the range of treatments included. Five studies compared different types of traction (e.g. auto‐traction versus manual traction or passive traction, continuous versus intermittent traction, inversion traction versus conventional traction) (Güvenol 2000; Letchuman 1993; Ljunggren 1984; Reust 1988; Tesio 1993). Four studies compared a standard physiotherapy programme (not including traction) with the same treatment with traction (Borman 2003; Fritz 2007; Harte 2007; Ozturk 2006). One study compared different types of underwater therapy, underwater traction being one of them (Konrad 1992).

Length of follow‐up

Fourteen studies reported short‐term follow‐up (one week) (Fritz 2007; Gudavalli 2006; Harte 2007; Larsson 1980; Ljunggren 1984; Ljunggren 1992; Ozturk 2006; Pal 1986; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Unlu 2008; Weber 1973; two in Weber 1984). Fifteen studies reported follow‐up at three to five weeks (Beurskens 1997; Bihaug 1978; Coxhead 1981; Fritz 2007; Konrad 1992; Lidström 1970; Lind 1974; Ljunggren 1984; Mathews 1975; Mathews 1988; Pal 1986, Reust 1988; Sherry 2001; Unlu 2008; Van der Heijden 1995). Fourteen studies reported follow‐up at nine to 16 weeks (Beurskens 1997; Bihaug 1978; Borman 2003; Coxhead 1981; Gudavalli 2006; Güvenol 2000; Harte 2007; Larsson 1980; Ljunggren 1984; Schimmel 2009; Tesio 1993; Unlu 2008; Van der Heijden 1995; Werners 1999). Five studies reported follow‐up at six months (Beurskens 1997; Gudavalli 2006; Harte 2007; Mathews 1988), or one year (Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Mathews 1988). One study did not report the timing at which the outcomes were measured (Walker 1982).

Risk of bias in included studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

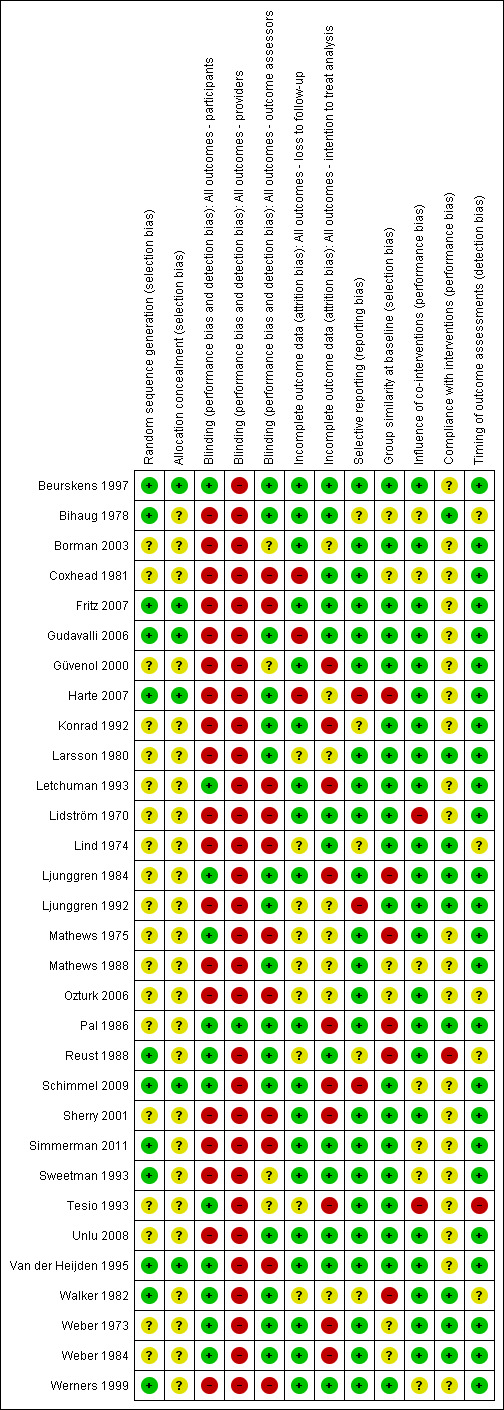

The results of the risk of bias analysis for the individual studies are summarized in Figure 1. Sixteen studies were considered to have a low risk of bias (Beurskens 1997; Fritz 2007; Gudavalli 2006; Larsson 1980; Letchuman 1993; Ljunggren 1984; Pal 1986; Schimmel 2009; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Unlu 2008; Van der Heijden 1995; Weber 1973; both trials in Weber 1984; Werners 1999), representing 1568 (57%) participants. Overall, risk of bias scores ranged from two to 10 (maximum possible risk of bias score was 12). Some of the studies that were considered to have a low risk of bias based on the The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool were considered to have a high risk of bias in the previous review (Larsson 1980; Letchuman 1993; Ljunggren 1984; Pal 1986; Sweetman 1993; Weber 1973; Weber 1984). Overall completeness of data was assessed in this review, whereas previously, dropout during intervention and dropout during follow‐up were scored. Selective reporting and timing of outcome assessments were not assessed previously.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The majority of the included studies did not properly report on their random and concealed allocation of treatment. In 20 of the included articles, there was no mention of the randomization procedure used and, in 26 of the included studies, it was unclear how concealment of treatment allocation was achieved. In six studies, both sequence generation and allocation procedure were conducted properly (Beurskens 1997; Fritz 2007; Gudavalli 2006; Harte 2007; Schimmel 2009; Van der Heijden 1991). In an additional six studies, the sequence generation was conducted properly, but the concealment of allocation was inadequately described (Bihaug 1978; Reust 1988; Simmerman 2011; Sweetman 1993; Walker 1982; Werners 1999). In the remaining studies, both randomization and allocation procedure were inadequately described or not mentioned at all. The authors claimed these studies were RCTs in the description of their methods and, therefore, these studies were included nevertheless.

Blinding

Blinding of outcomes was not achieved in the majority of the included studies. Blinding of the outcome assessor was achieved in 17 studies (Beurskens 1997; Bihaug 1978; Gudavalli 2006; Harte 2007; Konrad 1992; Larsson 1980; Ljunggren 1984; Ljunggren 1992; Mathews 1988; Pal 1986; Reust 1988; Schimmel 2009; Unlu 2008; Walker 1982; Weber 1973; both trials in Weber 1984), blinding of participants in 12 studies (Beurskens 1997; Letchuman 1993; Ljunggren 1984; Mathews 1975; Pal 1986; Reust 1988; Schimmel 2009; Tesio 1993; Van der Heijden 1995; Walker 1982; Weber 1973; Weber 1984), and blinding of care providers only in one study (Pal 1986). All of the studies that attempted to blind the participants to the assigned intervention did so by providing a sham treatment, with the exception of Tesio 1993. None of the studies evaluated the success of blinding post‐treatment. It should be noted that blinding of care providers of traction is impossible in most cases. It is disputable whether the outcome is likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding of care providers when it comes to assessing subjective measures such as pain intensity and functional status, as mentioned earlier. However, in the case of objective outcome measures, blinding is of importance.

Incomplete outcome data

In three studies, loss to follow‐up exceeded 20% of the study population (Coxhead 1981; Harte 2007), or significantly more subjects were lost to follow‐up in one treatment group compared the number of subjects that were lost to follow‐up in the other group (Gudavalli 2006). Loss to follow‐up never exceeded 23%. In nine of the included trials, it was not clear how many subjects were lost to follow‐up (Larsson 1980; Lind 1974; Ljunggren 1992; Mathews 1975; Mathews 1988; Ozturk 2006; Reust 1988; Tesio 1993; Walker 1982).

Selective reporting

None of the included RCTs had a published protocol in any of the protocol databases that were searched. The study's prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes as reported in the article itself were compared with the reported outcomes. One study indicated that VAS scores, overall improvement and improvement in the straight leg raising test had been recorded at three and six months but did not report this (Harte 2007), while in another study, improvement in mobility, activities of daily living and the straight leg raising test were measured but not reported (Ljunggren 1992), and similarly for all outcome assessments at two and six weeks in another study (Schimmel 2009).

Other potential sources of bias

We identified no other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Section (1) of the results describes those studies in which a mixed group of people with LBP is involved, i.e., some with and some without sciatica. In section (2), the participant populations include only people with LBP with sciatica. Section (3) describes the studies that included only people with LBP without sciatica. Studies that included more than 66% of participants with sciatica were categorized as studies that included people with sciatica.

(1) Traction for a mixed group of people with low‐back pain, some with and some without sciatica

(1a) Traction versus placebo, sham or no treatment

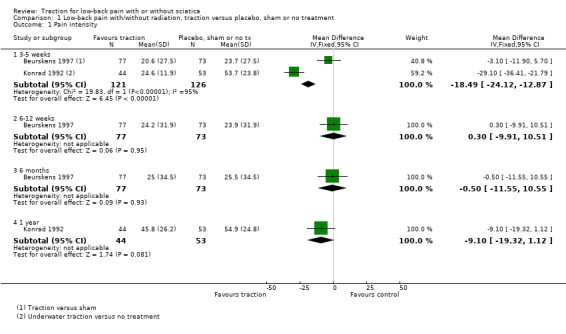

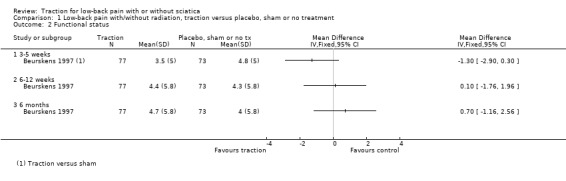

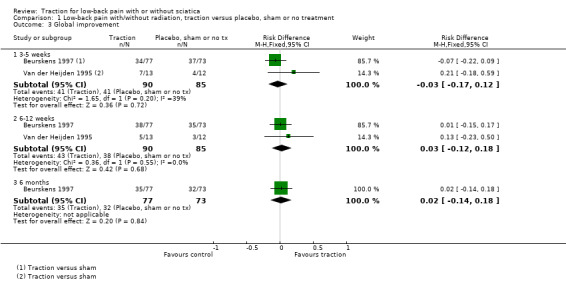

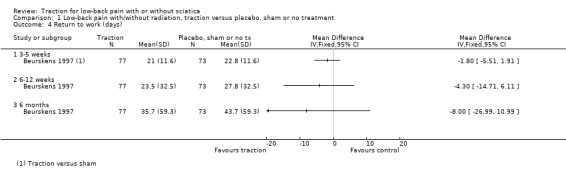

There was low‐quality evidence that decrease in pain intensity was greater in participants treated with traction at three to five weeks' follow‐up (MD 18.49 points on the VAS, 95% CI ‐24.12 to ‐12.87) (Beurskens 1997; Konrad 1992). However, the difference in pain intensity at one year' follow‐up had an MD of only 9 points on the VAS (95% CI ‐19.32 to 1.12), favouring traction (Konrad 1992). Moderate‐quality evidence indicated there was a small positive effect on functional status favouring the sham group at three to five weeks' follow‐up (1.3 points on the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), 95% CI ‐2.90 to 0.30) (Beurskens 1997). There was no difference in global improvement at three to five weeks (RD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.12) (Beurskens 1997; Van der Heijden 1995), or at six to 12 weeks (RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.18) (Beurskens 1997; Van der Heijden 1995). Moderate‐quality evidence showed mean time to return to work in the traction group was two days earlier (Beurskens 1997).

(1b) Physiotherapy with traction versus physiotherapy without traction

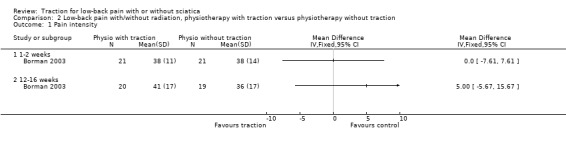

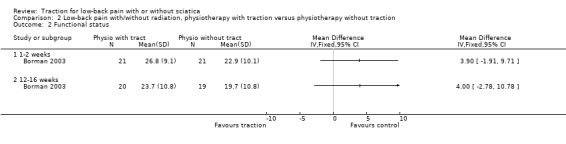

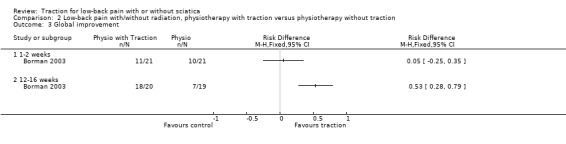

There was low‐quality evidence that there was no difference in pain intensity at one to two weeks' follow‐up between the two groups (Borman 2003). There was a small mean difference of 5 points on the VAS (95% CI ‐5.67 to 15.67) in favour of physiotherapy at 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up (Borman 2003). Short‐term and long‐term functional status as measured by the ODI was better in the traction group than the physiotherapy group (short term mean points: 4, 95% CI ‐1.91 to 9.71; long term: 95% CI ‐2.78 to 10.78) (Borman 2003). There was low‐quality evidence that global improvement at one to two weeks' follow‐up was the same for both groups, whereas at 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up, global improvement was higher in the traction group (RD 0.53, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.79) (Borman 2003).

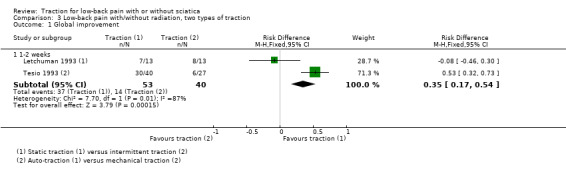

(1c) Different types of traction

One study with very‐low‐quality evidence showed that there was no difference in global improvement between participants undergoing static traction and participants undergoing intermittent traction (Letchuman 1993). Global improvement was higher in participants undergoing auto‐traction than in participants undergoing mechanical traction (RD 0.53, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.73) (Tesio 1993). Outcomes on pain intensity and functional status were reported only for those participants responding to treatment.

(1d) Traction versus other treatments

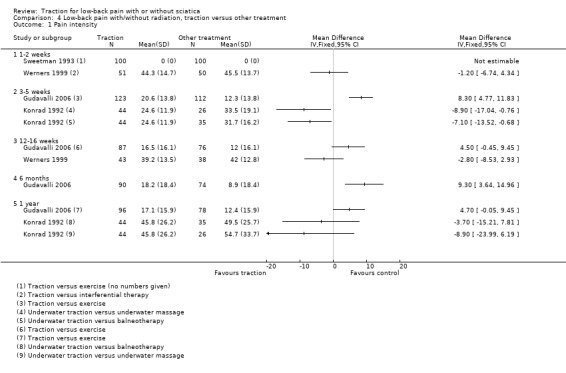

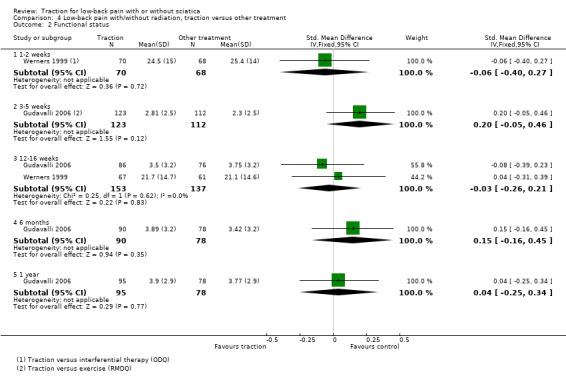

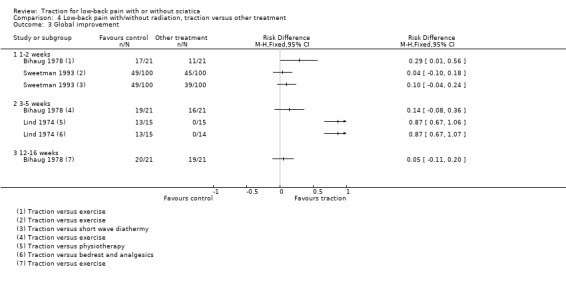

Six studies compared traction with another treatment (Bihaug 1978; Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Lind 1974; Sweetman 1993; Werners 1999). Traction was compared with varying other treatments: physiotherapy, exercise, short‐wave diathermy, interferential therapy, bed rest and analgesics.

There was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that pain intensity was slightly lower in participants treated with traction in the short‐term and the long‐term (Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Sweetman 1993; Werners 1999). MDs varied from 1 to 8 points on the VAS with a follow‐up duration varying from one week to one year. Moderate‐quality evidence showed that functional status as measured by the ODI or RMDQ was the same for both groups at one to two weeks, 12 to 16 weeks and one year' follow‐up (Gudavalli 2006; Werners 1999). There was a small difference in favour of the control group at three to five weeks (MD 0.2, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.46) and at six months (0.15 points, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.45) (Gudavalli 2006). There was a very small difference in global improvement favouring traction at 12 to 16 weeks (Bihaug 1978) (RD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.20), for which there was high‐quality evidence. The difference in global improvement at three to five weeks was much higher with an RD of 0.14 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.36) (Bihaug 1978) and 0.87 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.07) favouring traction (Lind 1974). However, the quality of evidence supporting this difference was very low.

(2) Traction for people with low‐back pain and sciatica

(2a) Traction versus placebo, sham or no treatment for people with a mix of acute, subacute and chronic low back pain with sciatica

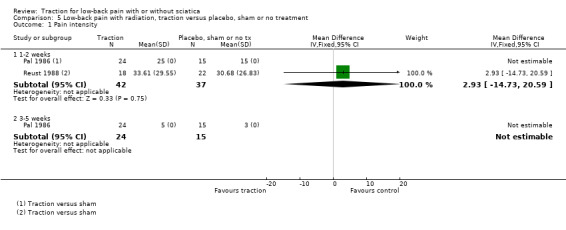

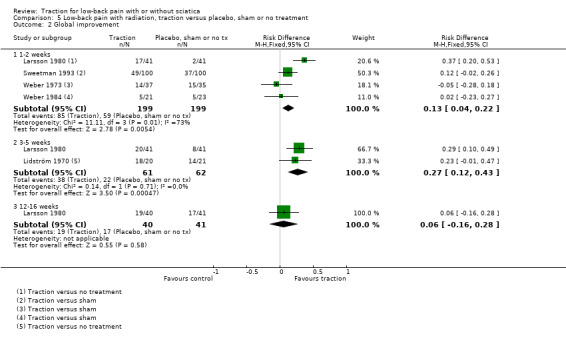

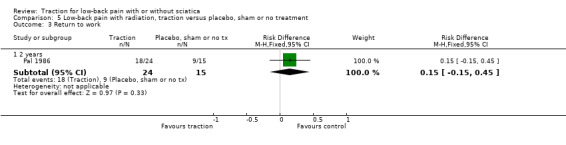

Low‐quality evidence suggested that there was a small effect on pain intensity in favour of the sham group (MD 2.93 points on the VAS scale, 95% CI ‐14.73 to 20.59) at one to two weeks' follow‐up (Pal 1986; Reust 1988), and at three to five weeks' follow‐up (Pal 1986). There was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that global improvement rates were higher in participants receiving traction at one to two weeks' follow‐up (RD 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.22) (Larsson 1980; Sweetman 1993; Weber 1973; Weber 1984), and three to five weeks' follow‐up (RD 0.27, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.43) (Larsson 1980; Lidström 1970). However, at 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up, there was no significant difference in global improvement between the two groups (RD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.28) (Larsson 1980). Moderate‐quality evidence suggested that more participants receiving traction returned to work compared with participants receiving sham treatment (RD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.45) (Pal 1986).

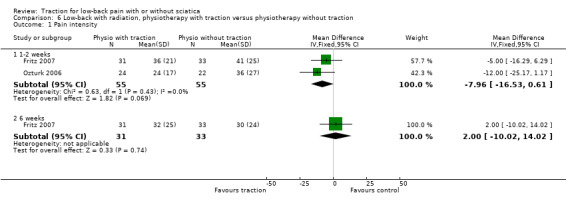

(2b) Physiotherapy with traction versus physiotherapy without traction

Although moderate‐quality evidence showed a lower mean pain intensity in the traction group (a difference of 7.96 points on the VAS, 95% CI ‐16.53 to 0.61) at one to two weeks' follow‐up (Fritz 2007; Ozturk 2006), the difference in mean pain intensity between the two groups was 2.00 points (95% CI ‐10.02 to 14.02) in favour of the physiotherapy group at six weeks' follow‐up (Fritz 2007). Functional status was measured by both the ODI and the RMDI. There was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that there was no difference in functional outcome at one to two weeks', six to 12 weeks', 12 to 16 weeks and six months' follow‐up (Fritz 2007; Harte 2007). Low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence showed no difference in global improvement at one to two weeks' (Ozturk 2006), three to five weeks' (Coxhead 1981), six weeks' (Fritz 2007) and 12 to 16 weeks' (Coxhead 1981) follow‐up.

(2c) Different types of traction

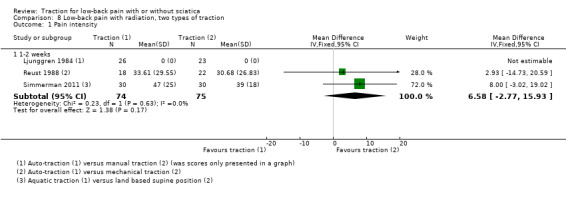

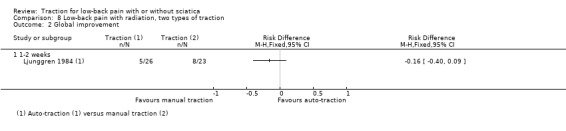

We found three RCTs that compared two types of traction and reported on pain intensity (Ljunggren 1984; Reust 1988; Simmerman 2011). Reust 1988 compared auto‐traction with mechanical traction. There was a small effect in favour of auto‐traction (2.9 points on the VAS, 95% CI ‐14.73 to 20.59). Simmerman 2011 compared aquatic traction to a land‐based supine position at one to two weeks' follow‐up. There was a small effect in favour of auto‐traction at one to two weeks' follow‐up (8 points on the VAS, 95% CI ‐3.02 to 19.02). One RCT was identified that compared two types of traction, auto‐traction versus manual traction, and reported on global improvement (Ljunggren 1984). There was a small effect in favour of manual traction at one to two weeks' follow‐up (RD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.09).

Although one more RCT compared two types of traction (Güvenol 2000), this study only reported P values.

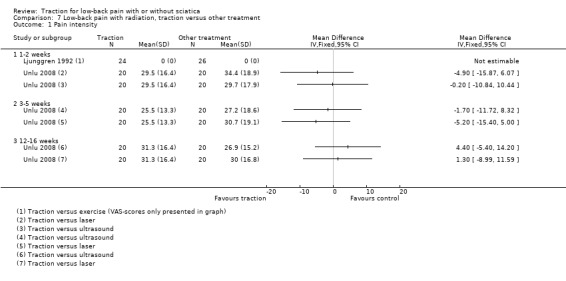

(2d) Traction versus other treatments

Three RCTs compared traction with other treatments and reported varying outcome measures (Lidström 1970; Ljunggren 1992; Unlu 2008). Traction was compared with physiotherapy, exercise, laser, ultrasound, manipulation and corset treatment.

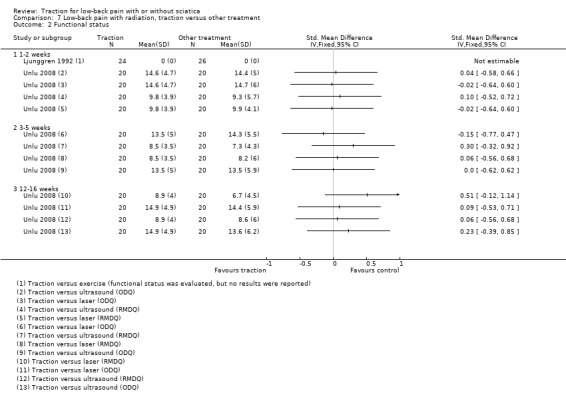

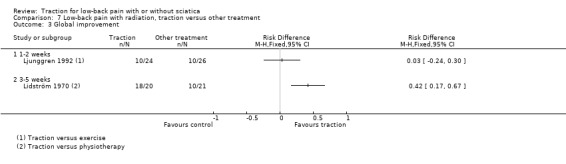

There was moderate‐quality evidence that mean pain intensity in the traction group was slightly lower at one to two weeks' follow‐up (Ljunggren 1992; Unlu 2008), and three to five weeks' follow‐up (Unlu 2008). The maximum MD in pain intensity was 4.9 points (95% CI ‐15.87 to 6.07) (Unlu 2008). However, at 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up the mean pain intensity in the traction group was higher (maximum MD 4.4 points, 95% CI ‐5.40 to 14.20) (Unlu 2008). There was no difference in functional status measured by the ODI or RMDI between the two groups at one to two weeks', three to five weeks' and 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up (Ljunggren 1992; Unlu 2008). There was low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that there is only a very small difference in global improvement between the two groups at one to two weeks' follow‐up (RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.30) (Ljunggren 1992), and three to five weeks' follow‐up (RD 0.42, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.67) (Lidström 1970).

(3) Traction for people with low‐back pain and without sciatica

(3a) Traction versus sham treatment

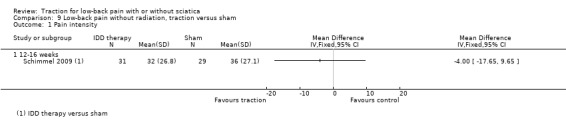

There was moderate‐quality evidence that there is a very small difference in pain intensity between the two groups, favouring the traction group by 4 points on the VAS (95% CI ‐17.65 to 9.65) (Schimmel 2009).

Adverse effects

Of the 32 studies, four stated that there were no adverse effects (Gudavalli 2006; Konrad 1992; Schimmel 2009; Walker 1982); seven studies reported some adverse effects, for example, increased pain in 11 of 14 inversion traction participants versus 2 of 13 conventional traction participants, and anxiety during treatment with "almost all of the inversion traction patients" (Güvenol 2000); increased pain in 31% of static traction group and 15% of intermittent traction group (Letchuman 1993); temporary deterioration in 4 of 24 of traction and 4 of 26 of exercise group (Ljunggren 1992); subsequent surgery in 7 of 83 in lumbar traction group versus none in control group (Mathews 1988); aggravation of neurological signs in 5 of 18 of traction group, 4 of 20 of light traction group and 4 of 20 of placebo group (Reust 1988); aggravation of symptoms in 5 of 43 of traction and 1 of 43 of sham (Weber 1973). Borman 2003 reported that 25% of the group receiving traction as part of standard physiotherapy and 37% of the physiotherapy without traction group felt "probably or definitely worse" at three‐month' follow‐up. The remaining 21 studies did not report adverse effects.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Many studies were identified on the effect of traction on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work in people with LBP. However, most evidence was imprecise and inconsistent and numerous studies carried substantial risk of bias. Many of the studies seemed to have sample sizes that were too small to detect a clinically significant difference. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in comparisons, outcomes and follow‐up durations prohibited us, among other reasons, from pooling the data and, therefore, we used a descriptive analysis in this review. The sample sizes per comparison mostly did not reach the threshold of 400 for continuous outcomes and 300 for dichotomous outcomes (Furlan 2009; Higgins 2011). Therefore, we put little trust in positive effects that emerged.

The included studies largely differed in their population, outcome measures, and scales and duration of follow‐up. Some studies included hospitalized participants with demonstrated herniated discs, neurological findings and sciatica, while other studies included people recruited from primary care or workers recruited through internal company newspapers. Some studies used the ODI, while others used the RMDI. Some studies reported on all four primary outcomes (pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work), whereas others only reported on one or two, which might suggest publication bias.

The studies showed small differences in effects between traction and other treatment options on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement and return to work at short term. The effect was even smaller at longer‐term follow‐up. Mostly the MD between the two groups favours the traction group, but not always. For most of the outcomes, no effects of traction were shown and when they were, the effects were too small to be clinically relevant. The minimum important difference (between groups) in changes (within groups) for pain intensity and functional status established by Ostelo 2008 were used to judge clinical relevancy. A clinically relevant effect was achieved in pain intensity at three to five weeks' follow‐up in people with and without sciatica undergoing traction when compared with sham treatment (Konrad 1992). A clinically relevant difference in changes in global improvement was seen in people with and without sciatica undergoing physiotherapy with traction at 12 to 16 weeks' follow‐up (RD 0.53) (Borman 2003), and in global improvement in people with and without sciatica undergoing traction when compared to other treatments at 12 to 16 weeks (RD 0.57) (Bihaug 1978; Lind 1974). However, in all of these cases, the effects did not reach statistical significance and they were based on low‐ to very‐low‐quality evidence, which means that we are very uncertain about the findings. Studies with a high risk of bias typically overestimate the effect compared to studies with a low risk of bias (Van Tulder 2009).

Two articles examined the level of physical force applied in the treatment and concluded that even a low level of force may be effective (Harte 2003; Krause 2000). Beurskens 1997 maintained that traction at levels below 25% of body weight and using a split table can be regarded as sham (or low‐dose) traction, and the sham traction group in their trial received treatment involving a force of 10% to 20% of the participant's body weight. In the other trials that classified their control groups as 'sham traction', the force applied varied (e.g. less than 25% of body weight in Van der Heijden 1995; 10 lb (4.5 kg) in Letchuman 1993; 1.8 kg in Pal 1986; 5 kg in Reust 1988; and a maximum of 20 lb (9 kg) in Mathews 1975). No differences between traction and sham traction were demonstrated in any of these trials.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We minimized review bias by performing an extensive database search. Publication bias could be an issue. The many small RCTs are more likely to be published when positive. Authors possibly may refrain from publishing when results are negative. However, the review authors consider that it is unlikely that large trials on the subject were not published. Many of the published studies did not have a published protocol and, therefore, it is difficult to ascertain to what extent studies did not publish their findings because the results did not prove to be favourable.

Quality of the evidence

Sixteen of the 32 included studies demonstrated a low risk of bias. Items that were scored predominantly negatively or unclear were randomization, concealment and blinding. The majority of the included studies did not properly report on their random and concealed allocation of treatment. In 20 of the included articles, there was no mention of the randomization procedure used and, in 26 of the included studies, it was unclear how concealment of treatment allocation was achieved. Blinding of outcomes was not achieved in the majority of the included studies. Blinding of the outcome assessor was achieved in 17 studies and blinding of participants in 12 studies. The latter reflects the number of trials in which sham or simulated traction was used. Blinding of the care provider is virtually impossible given the nature of the intervention. As a result, only one study achieved blinding of the care provider.

Furthermore, relatively few participants were identified for any of the principal outcome measurements and, as a result, none of the findings should be considered robust.

Potential biases in the review process

Although content area experts may have inside knowledge, may be familiar with current interests in their field and may be aware of pressing questions in their field, they may also have personal prejudices and idiosyncrasies. Experts with strong opinions may make it difficult to prevent bias (Gotzsche 2012). To harness bias in this review, two non‐experts (IW and ISW) in this area, trained in reviewing literature, were involved in writing this review. Data from previous reviews were verified, checked and changed where necessary by these two review authors.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In general, the results and conclusions of this updated review are consistent with the previous version of the review, namely that traction is no better than standard interventions for (acute, subacute and chronic) LBP. In this review, we discussed one high‐quality study that included only people without sciatica that was not included in the previous review (Schimmel 2009). This study showed that traction in people without sciatica is no better than sham treatment. There was no significant difference between the traction and sham group in pain intensity or functional status.

Our findings were consistent with those reported in other systematic reviews on the subject (Chou 2007; Gay 2008). One review concluded there was insufficient data to draw firm conclusions on the clinical effect of traction (Van Middelkoop 2011). Only one RCT discussing the effect of traction was included in this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Effects of traction alone or as part of a package for people with low‐back pain (LBP) with and without sciatica have not been shown. There are some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing benefit of traction, but the limited quality evidence from these small moderate to high risk of bias studies show very small effects that are not clinically relevant. In summary, to date the use of traction as treatment for non‐specific LBP is not supported by the best available evidence.

Implications for research.

New, large, high‐quality studies may change the point estimate and its accuracy, but it should be noted that such change may not necessarily favour traction. Therefore, little priority should be given to new studies on the effect of traction treatment alone or as part of a package.

Feedback

Personal experience with traction, 2 January 2010

Summary

Individual shared personal experience with traction as a positive alternative to surgery for his back pain.

Personal correspondence between Managing Editor and contributor. Not appropriate to include.

Reply

Contributor responded appreciatively to correspondence.

Contributors

Victoria Pennick, Managing Editor, Cochrane Back Review Group

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 May 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions not changed. |

| 13 May 2013 | New search has been performed | Review updated. Seven new RCTs were incorporated. The review was performed using the latest methods concerning risk of bias assessment and reporting as stated in the Handbook. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 4, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 January 2010 | Amended | Feedback added |

| 27 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 January 2007 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions were not changed by the addition of the newly identified trial. Author by‐line changed. |

| 31 October 2006 | New search has been performed | There was only one additional trial identified for this update. It did not change the conclusions. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank Dr. J Clarke for her contribution to the previous review (Clarke 2006a), of which this is an update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1966 to August 2013)

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab,ti.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab,ti.

trial.ab,ti.

groups.ab,ti.

or/1‐8

(animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

9 not 10

dorsalgia.ti,ab.

exp Back Pain/

backache.ti,ab.

exp Low Back Pain/

(lumbar adj pain).ti,ab.

coccyx.ti,ab.

coccydynia.ti,ab.

sciatica.ti,ab.

sciatic neuropathy/

spondylosis.ti,ab.

lumbago.ti,ab.

or/12‐22

exp Spine/

discitis.ti,ab.

exp Spinal Diseases/

(disc adj degeneration).ti,ab.

(disc adj prolapse).ti,ab.

(disc adj herniation).ti,ab.

spinal fusion.sh.

spinal neoplasms.sh.

(facet adj joints).ti,ab.

intervertebral disk.sh.

intervertebral disc.sh.

Intervertebral Disc Displacement.sh.

postlaminectomy.ti,ab.

arachnoiditis.ti,ab.

(failed adj back).ti,ab.

or/24‐38

23 or 39

11 and 40

exp Traction/

exp "Physical Therapy (Specialty)"/

42 or 43

exp Fractures, Bone/

44 not 45

11 and 41 and 46

EMBASE Ovid (1980 to August 2013)

Clinical Article/

exp Clinical Study/

Clinical Trial/

Controlled Study/

Randomized Controlled Trial/

Major Clinical Study/

Double Blind Procedure/

Multicenter Study/

Single Blind Procedure/

Phase 3 Clinical Trial/

Phase 4 Clinical Trial/

crossover procedure/

placebo/

or/1‐13

allocat$.mp.

assign$.mp.

blind$.mp.

(clinic$ adj25 (study or trial)).mp.

compar$.mp.

control$.mp.

cross?over.mp.

factorial$.mp.

follow?up.mp.

placebo$.mp.

prospectiv$.mp.

random$.mp.

((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).mp.

trial.mp.

(versus or vs).mp.

or/15‐29

14 and 30

human/

Nonhuman/

exp ANIMAL/

Animal Experiment/

33 or 34 or 35

32 not 36

31 not 36

37 and 38

38 or 39

dorsalgia.mp.

back pain.mp.

exp LOW BACK PAIN/

exp BACKACHE/

(lumbar adj pain).mp.

coccyx.mp.

coccydynia.mp.

sciatica.mp.

exp ISCHIALGIA/

spondylosis.mp.

lumbago.mp.

or/41‐50

exp SPINE/

discitis.mp.

exp Spine Disease/

(disc adj degeneration).mp.

(disc adj prolapse).mp.

(disc adj herniation).mp.

spinal fusion.mp.

spinal neoplasms.mp.

(facet adj joints).mp.

intervertebral disk.mp.

postlaminectomy.mp.

arachnoiditis.mp.

(failed adj back).mp.

or/53‐65

52 or 66

40 and 67

exp traction therapy/

exp fracture/

69 not 70

68 and 71

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library, 2012 Issue 8)

MeSH descriptor Back Pain explode all trees

dorsalgia

backache

MeSH descriptor Low Back Pain explode all trees

(lumbar next pain) or (coccyx) or (coccydynia) or (sciatica) or (spondylosis)

MeSH descriptor Sciatica explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Spine explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Spinal Diseases explode all trees

(lumbago) or (discitis) or (disc near degeneration) or (disc near prolapse) or (disc near herniation)

spinal fusion

facet near joints

MeSH descriptor Intervertebral Disk explode all trees

postlaminectomy

arachnoiditis

failed near back

MeSH descriptor Cauda Equina explode all trees

lumbar near vertebra*

spinal near stenosis

slipped near (disc* or disk*)

degenerat* near (disc* or disk*)

stenosis near (spine or root or spinal)

displace* near (disc* or disk*)

prolap* near (disc* or disk*)

(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23)

MeSH descriptor Traction explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Physical Therapy (Specialty) explode all trees

(#25 OR #26)

MeSH descriptor Fractures, Bone explode all trees

(#27 AND NOT #28)

(#24 AND #29)

CINAHL (Ebsco) (January 2006 to August 2013)

S53 S49 and S52 S52 S50 NOT S51 S51 (MH "Fractures+") S50 (MH "Traction") OR "traction" S49 S47 or S48 S48 S35 or S43 or S47 S47 S44 or S45 or S46 S46 "lumbago" S45 (MH "Spondylolisthesis") OR (MH "Spondylolysis") S44 (MH "Thoracic Vertebrae") S43 S36 or S37 or S38 or S39 or S40 or S41 or S42 S42 lumbar N2 vertebra S41 (MH "Lumbar Vertebrae") S40 "coccydynia" S39 "coccyx" S38 "sciatica" S37 (MH "Sciatica") S36 (MH "Coccyx") S35 S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 or S34 S34 lumbar N5 pain S33 lumbar W1 pain S32 "backache" S31 (MH "Low Back Pain") S30 (MH "Back Pain+") S29 "dorsalgia" S28 S26 NOT S27 S27 (MH "Animals") S26 S7 or S12 or S19 or S25 S25 S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 S24 volunteer* S23 prospectiv* S22 control* S21 followup stud* S20 follow‐up stud* S19 S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 S18 (MH "Prospective Studies+") S17 (MH "Evaluation Research+") S16 (MH "Comparative Studies") S15 latin square S14 (MH "Study Design+") S13 (MH "Random Sample") S12 S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 S11 random* S10 placebo* S9 (MH "Placebos") S8 (MH "Placebo Effect") S7 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 S6 triple‐blind S5 single‐blind S4 double‐blind S3 clinical W3 trial S2 "randomi?ed controlled trial*" S1 (MH "Clinical Trials+")

Appendix 2. Criteria for assessing risk of bias for internal validity

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomized sequence

There is a low risk of selection bias if the investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table, using a computer random number generator, coin tossing, shuffling cards or envelopes, throwing dice, drawing of lots, minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random).

There is a high risk of selection bias if the investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process, such as: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth, date (or day) of admission, hospital or clinic record number; or allocation by judgement of the clinician, preference of the participant, results of a laboratory test or a series of tests, or availability of the intervention.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment

There is a low risk of selection bias if the participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomization); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

There is a high risk of bias if participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; or other explicitly unconcealed procedures.

Blinding of participants

Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants during the study

There is a low risk of performance bias if blinding of participants was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of personnel/care providers (performance bias)

Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by personnel/care providers during the study

There is a low risk of performance bias if blinding of personnel was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias)

Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors

There is low risk of detection bias if the blinding of the outcome assessment was ensured and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding, or:

for participant‐reported outcomes in which the participant was the outcome assessor (e.g. pain, disability): there is a low risk of bias for outcome assessors if there is a low risk of bias for participant blinding (Boutron 2005);

for outcome criteria that are clinical or therapeutic events that will be determined by the interaction between participants and care providers (e.g. co‐interventions, length of hospitalization, treatment failure), in which the care provider is the outcome assessor: there is a low risk of bias for outcome assessors if there is a low risk of bias for care providers (Boutron 2005);

for outcome criteria that are assessed from data from medical forms: there is a low risk of bias if the treatment or adverse effects of the treatment could not be noticed in the extracted data (Boutron 2005).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data

There is a low risk of attrition bias if there were no missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data were unlikely to be related to the true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data were balanced in numbers, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with the observed event risk was not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, the plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes was not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size, or missing data were imputed using appropriate methods (if dropouts are very large, imputation using even 'acceptable' methods may still suggest a high risk of bias) (Van Tulder 2003). The percentage of withdrawals and dropouts should not exceed 20% for short‐term follow‐up and 30% for long‐term follow‐up and should not lead to substantial bias (these percentages are commonly used but arbitrary, not supported by literature) (Van Tulder 2003).

Selective Reporting (reporting bias)

Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting

There is low risk of reporting bias if the study protocol is available and all of the study's prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the prespecified way, or if the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon).