Abstract

Background

Prolonged labour can lead to increased maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity due to increased risks of maternal exhaustion, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis, fetal distress and asphyxia and requires early detection and appropriate clinical response. The risks for complications of prolonged labour are much greater in poor resource settings. Active management of labour versus physiological, expectant management, has shown to decrease the occurrence of prolonged labour. Administering antispasmodics during labour could also lead to faster and more effective dilatation of the cervix. Interventions to shorten labour, such as antispasmodics, can be used as a preventative or a treatment strategy in order to decrease the incidence of prolonged labour. As the evidence to support this is still largely anecdotal around the world, there is a need to systematically review the available evidence to obtain a valid answer.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antispasmodics on labour in term pregnancies.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (28 February 2013), the ProQuest dissertation and thesis database, the dissertation database of the University of Stellenbosch and Google Scholar (28 February 2013) and reference lists of articles. We also contacted pharmaceutical companies and experts in the field. We did not apply language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing antispasmodics with placebo or no medication in women with term pregnancies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened abstracts and selected studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and extracted data. Data were checked for accuracy. We contacted trial authors when data were missing.

Main results

Twenty‐one trials (n = 3286) were included in the review. Seventeen trials (n = 2617) were included in the meta‐analysis. Antispasmodics used included valethamate bromide, hyoscine butyl‐bromide, drotaverine hydrochloride, rociverine and camylofin dihydrochloride. Most studies included antispasmodics as part of their package of active management of labour. Overall, the quality of studies was poor, as only four trials were assessed as low risk of bias. Thirteen trials (n = 1995) reported on the duration of first stage of labour, which was significantly reduced by an average of 74.34 minutes when antispasmodics were administered (mean difference (MD) ‐74.34 minutes; 95% confidence Interval (CI) ‐98.76 to ‐49.93). Seven studies (n = 797) reported on the total duration of labour, which was significantly reduced by an average of 85.51 minutes (MD ‐85.51 minutes; 95% CI ‐121.81 to ‐49.20). Six studies (n = 820) had data for the outcome: rate of cervical dilatation. Administration of antispasmodics significantly increased the rate of cervical dilatation by an average of 0.61 cm/hour (MD 0.61 cm/hour; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.88). Antispasmodics did not affect the duration of second and third stage of labour. The rate of normal vertex deliveries was not affected either. Only one study explored pain relief following administration of antispasmodics and no conclusions can be drawn on this outcome. There was significant heterogeneity for most outcomes and therefore, we undertook random‐effects meta‐analysis. Subgroup analysis was undertaken to explore heterogeneity, but remained largely unexplained. Maternal and neonatal adverse events were reported inconsistently. The main maternal adverse event reported was tachycardia. No serious neonatal adverse events were reported.

Authors' conclusions

There is low quality evidence that antispasmodics reduce the duration of first stage of labour and increase the cervical dilatation rate. There is very low quality evidence that antispasmodics reduce the total duration of labour. There is moderate quality evidence that antispasmodics do not affect the rate of normal vertex deliveries. There is insufficient evidence to make any conclusions regarding the safety of these drugs for both mother and baby. Large, rigorous randomised controlled trials are needed to evaluate the effect of antispasmodics on prolonged labour and to evaluate their effect on labour in a context of expectant management of labour.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Labor Stage, First; Labor Stage, First/drug effects; Obstetric Labor Complications; Obstetric Labor Complications/drug therapy; Parasympatholytics; Parasympatholytics/adverse effects; Parasympatholytics/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tachycardia; Tachycardia/chemically induced

Plain language summary

Antispasmodics for labour

A woman who is in active labour for too long (usually set at more than 12 hours) is at risk of becoming exhausted and developing complications such as infection and excessive bleeding. The unborn baby can also be harmed, showing distress and low oxygenation (asphyxia). It is common practice to intervene in the labouring process to avoid this by rupturing membranes (breaking the waters), giving medications to speed up contractions and providing ongoing support. Antispasmodics are drugs that are usually taken to relieve cramps. They work either by direct relaxation of muscle or by interfering with the message sent by the nerves to the muscle to contract. It is thought that these drugs may help with opening the womb (dilatation of the cervix), when given during labour as a preventative or a treatment strategy. This would shorten the time spent in labour. Evidence was sought to support this idea. Twenty‐one randomised controlled studies with a total of 3286 participants were included. The data were combined in an analysis to get an overall result. All types of antispasmodics were given at the beginning of established labour. They decreased the first stage of labour, the time from beginning of labour until the baby is about to be born, by 49 to 98 minutes, as well as the total duration of labour, from the beginning of labour until the delivery of the afterbirth, by 49 to 121 minutes. The drugs did not affect the number of women requiring emergency caesarean sections and did not have serious side effects for either mother or her baby. The most commonly reported adverse events for the mothers were fast heart rates and mouth dryness, but since both maternal and neonatal adverse events were poorly reported, more information is needed to make conclusions about the safety of these drugs during labour. The included studies were mostly of poor quality and good studies are needed to assess what happens when these drugs are given to women whose labour is already prolonged.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antispasmodics versus control.

| Antispasmodics versus control | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women in labour Settings: Hospital setting Intervention: Antispasmodics Comparison: Control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Antispasmodics | |||||

| Duration of first stage of labour minutes | 173 to 346.31 | The mean duration of first stage of labour in the intervention groups was 74.34 lower (98.76 to 49.93 lower) | 1995 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| Duration of second stage of labour minutes | 16.5 to 58 | The mean duration of second stage of labour in the intervention groups was 2.68 lower (5.98 lower to 0.63 higher) | 1297 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| Duration of third stage of labour minutes | 5.52 to8.3 | The mean duration of third stage of labour in the intervention groups was 0.06 lower (0.52 lower to 0.4 higher) | 765 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

|

Total duration of labour minutes |

192.2 to 413.9 | The mean total duration of labour (min) in the intervention groups was 85.51 lower (121.81 to 49.2 lower) | 797 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| Rate of cervical dilatation cm/h | 1.01 to 2.5 | The mean rate of cervical dilatation in the intervention groups was 0.61 higher (0.34 to 0.88 higher) | 820 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| Rate of normal vertex deliveries | Study population | RR 1.02 (1 to 1.05) | 2319 (16 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 905 per 1000 | 923 per 1000 (905 to 950) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 925 per 1000 | 943 per 1000 (925 to 971) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 High risk for selection and incomplete reporting of outcomes in most studies 2 Significant, unexplained heterogeneity present 3 Wide 95% confidence interval

Background

Description of the condition

Improving maternal health (the fifth Millennium Development Goal) and decreasing maternal mortality remains one of the main health concerns worldwide. Some progress has been made towards achieving the target of reducing maternal mortality by three‐quarters between 1990 and 2015, as the global maternity mortality ratio (MMR) in 2008 was 260 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to 430/100,000 live births in 1990 (WHO 2010). However, in Sub‐Saharan Africa, the burden is significant, with an MMR of 640/100,000 live births in 2008 (WHO 2010).

According to an analysis conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Khan 2006), 4.1% of maternal deaths in Africa were due to obstructed labour. The percentage for Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, was 9.4% and 13.4% respectively. The leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide is haemorrhage (developed countries 13.4%; Africa 33.9%; Asia 30.8%; Latin America and the Caribbean 20.8%). This includes postpartum haemorrhage, although the proportion was not specified (Khan 2006).

Prolonged labour can lead to increased maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity due to increased risks of maternal exhaustion, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis, fetal distress and asphyxia and requires early detection and appropriate clinical response. The causes of prolonged labour relate to maternal age, induction of labour, prelabour rupture of membranes, early admission to the labour ward, epidural analgesia and high levels of maternal stress hormones, but are unknown in most cases (Dencker 2009). The risks for complications of prolonged labour are much greater in poor resource settings (Neilson 2003). It is difficult to give a clear definition for prolonged labour. In practice, as recommended by the WHO maternal health and safe motherhood programme (WHO 1994), a woman should be transferred to a higher level of care if her rate of cervical dilatation (according to the partogram) becomes less than 1 cm/hour, and requires prompt, appropriate management if it is less than 1 cm in four hours (Lavender 2009). In addition, a recent review to determine the “slowest‐yet‐normal” dilatation rate amongst primigravid women (Neal 2010), determined that this dilatation rate approximates 0.5 cm/hour and that expectations of a faster dilatation rate (1 cm/hour) can lead to unnecessary interventions aiming to accelerate labour.

The concept of “active management of labour” (O'Driscoll 1973) was developed to assure a woman that her labour would not exceed 12 hours. Anything beyond that constituted prolonged labour. This package of care includes accurate and early diagnosis of the first stage of labour, early artificial rupture of membranes, ongoing support of the woman in labour by a professional caregiver and augmentation of labour with oxytocin (O'Driscoll 1994). Active management of labour versus physiological, expectant management, has shown to decrease the occurrence of prolonged labour (more than 12 hours). A Cochrane review found that active management significantly shortened the duration of labour by 1.27 hours, while the first stage of labour was significantly reduced by 1.56 hours. It also showed a small reduction in the rate of caesarean sections. There was no significant difference in maternal and neonatal morbidity (Brown 2008). Wei 2009 showed that early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin augmentation, as a preventative strategy with mild delays in progress, leads to a reduction of 1.16 hours in the duration of labour.

Description of the intervention

Administering antispasmodics during labour could lead to faster and more effective dilatation of the cervix (Samuels 2009).

Antispasmodics are drugs that relieve spasms of smooth muscle tissue and have either musculotropic or neurotropic effects. The cervix is composed of connective tissue and smooth muscle, innervated by parasympathetic nerve fibres. Smooth muscle constitutes about 15% of the cervix (Leppert 1995), which is mainly found just below the internal os (Buhimschi 2003).

Musculotropic antispasmodics directly relax smooth muscles. They are phosphodiesterase type IV inhibitors, structurally related to papaverine, have mild Calcium (Ca)‐channel blocking effects, no anticholinergic effects and act directly on smooth muscle cells, inhibiting spasm (Sommers 2002).

Neurotropic antispasmodics break the connection between the parasympathetic nerve and the smooth muscle.They are parasympatholytics acting as antagonists of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors, thus inhibiting muscle spasm (Samuels 2009; Sommers 2002).

Antispasmodics are commonly administered during labour in both developing and developed countries, although there is a paucity of scientific reports validating this. In India, drotaverine hydrochloride, an antispasmodic drug, forms part of their “Programmed Labour Protocol” to decrease the pain and the duration of labour (Yuel 2008). It is used in conjunction with amniotomy, oxytocin augmentation and administration of tramadol for pain relief.

There are a number of case‐reports, prospective studies and clinical trials describing the effects of antispasmodics during labour. A prospective study by Sirohiwal 2005 found that administration of hyoscine‐butyl bromide suppositories during labour significantly shortened the duration of the first stage of labour.

Adverse effects of these drugs are rare at therapeutic dosages and include dryness of the mouth, visual disturbances, tachycardia, drowsiness and fatigue. Some patients may experience paradoxical stimulation and excitation (Gibbon 2005).

How the intervention might work

As shown in studies conducted in India and elsewhere (Sirohiwal 2005; Yuel 2008), antispasmodics could be used as accelerators of labour. Although the exact mechanism of action of cervical dilatation and the influence of antispasmodics thereon is still somewhat unclear, more effective dilatation could lead to an accelerated labour.

Antispasmodics can be used in conjunction with the package of active management of labour, as has been done in India and across the world, or on its own. In the latter case, the general use of oxytocin would be reduced. Oxytocin, although widely used, has been described as the drug most commonly related to preventable adverse events during labour and has a very unpredictable therapeutic index (Clark 2009).

Furthermore, active management of labour as a whole package, or parts thereof, and other interventions to shorten labour, such as antispasmodics, can be used as a preventative strategy or a treatment strategy in order to decrease the incidence of prolonged labour. This depends on the setting, availability of resources and maternal preferences.

Why it is important to do this review

The use of antispasmodics as accelerators of labour is largely anecdotal around the world. The results of the first version of the review showed that there was low quality evidence that antispasmodics reduced the duration of the first stage of labour and very low quality evidence that they reduced the total duration of labour. The WHO is updating their augmentation of labour guidelines in 2013 and as this review was identified as one of the reviews to feed into the guideline, it is important to include all recent studies in this updated version of the review. Considering all studies addressing this question and interpreting the results in light of the quality of the studies will help policy makers and clinicians to make well‐informed decisions about the use of antispasmodics during labour.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the effects of antispasmodics on labour in term pregnancies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials for inclusion in this review and did not include quasi‐randomised controlled trials, cluster‐randomised trials or trials using a cross‐over design. We included studies available only as an abstract, if they reported on all the necessary information.

Types of participants

Primi‐ and multigravid women with term pregnancies (equal to or greater than 37 weeks' gestation) at the time of delivery; with spontaneous onset and induction of labour; low‐ and high‐risk pregnancies; active and expectant management of labour.

Types of interventions

We considered studies where any antispasmodic agent was administered during any stage of labour by means of oral, rectal, intramuscular or intravenous route compared with a control group (placebo or no medication) for inclusion in the review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes were the direct effect of antispasmodic drugs on labour.

Duration of labour.

Rate of cervical dilatation.

Pain relief.

Type of delivery (rate of normal vertex deliveries).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal adverse events: these included any maternal adverse event, defined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions Reviews (Higgins 2011) as any "unfavourable outcome that occurs during or after the use of a drug or other intervention but not necessarily caused by it".

Neonatal adverse events: this included any fetal or neonatal adverse event, defined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions Reviews (Higgins 2011), as any "unfavourable outcome that occurs during or after the use of a drug or other intervention but not necessarily caused by it".

Maternal satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (28 Febuary 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched the ProQuest dissertation and thesis database, the dissertation database of the University of Stellenbosch and Google Scholar (28 February 2013) (seeAppendix 1 for search terms used).

Searching other resources

We contacted experts in the field and relevant pharmaceutical companies that manufacture antispasmodics, but did not receive any additional study reports.

We also scanned reference lists of included papers for additional studies.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (either Anke Rohwer (AR) and Taryn Young (TY) or AR and Oswell Khondowe (OK)) independently reviewed the search output. We screened titles and abstracts of search results to exclude irrelevant studies. We then retrieved full text articles of seemingly relevant studies and examined them to see whether they met the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form. For eligible studies, two review authors (either AR and TY or AR and OK) extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked it for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (either AR and TY or AR and OK) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions Reviews (Higgins 2011). We contacted authors for missing information and resolved any disagreement by discussion.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions Reviews (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it as likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals, and for continuous data, we used the mean difference. All outcomes were measured in the same way between trials.

Unit of analysis issues

We dealt with studies with multiple treatment groups as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions Reviews (Higgins 2011). If studies had two intervention groups with different antispasmodics and one control group, we included the two different intervention groups in the meta‐analysis as separate intervention groups, but divided the control group in two (Ramsay 2003).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and analysed all participants in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots when outcomes included more than 10 studies. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually, and used formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we used the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we used the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If we detected asymmetry in any of these tests or by a visual assessment, we performed exploratory analyses to investigate it

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or when we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. We treated the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials.

When using random‐effects analyses, we presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated substantial heterogeneity using subgroup analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following pre‐specified subgroup analyses.

Type of antispasmodic (musculotropic drugs versus neurotropic drugs).

Route of administration (intravenous administration versus intramuscular administration).

Gravidity of women (primigravidas versus multigravidas).

Type of labour (spontaneous labour versus induced labour.

We also added three more non pre‐specified subgroups:

Type of management of labour (active management versus expectant management).

Type of pregnancy (high risk versus low risk).

Studies excluding versus studies including caesarean sections in their analysis.

We used the following outcomes in subgroup analysis.

Duration of labour.

Rate of cervical dilatation.

Pain relief.

Type of delivery.

For fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analyses, we assessed differences between subgroups by interaction tests. For random‐effects and fixed‐effect meta‐analyses using methods other than inverse variance, we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicated a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis on primary outcomes, to see what effect the exclusion of studies with high risk of bias (for allocation concealment, and incomplete outcome data) had on the overall result of the meta‐analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

September 2011 search

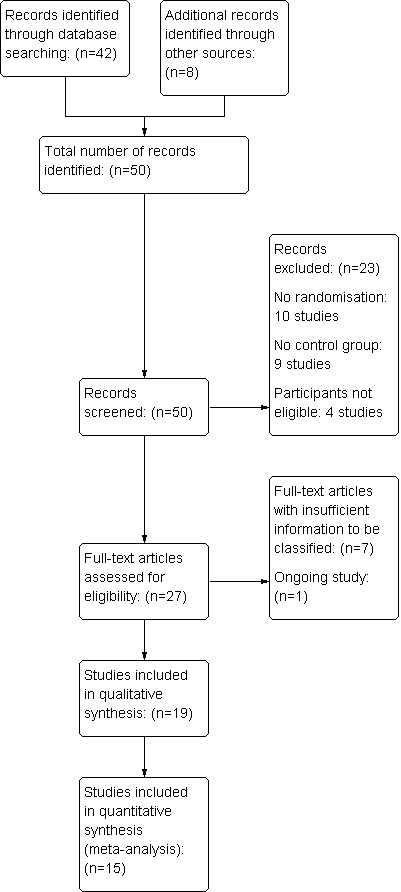

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Register retrieved 42 trial reports. The search of the dissertation databases did not retrieve additional studies and a search on Google Scholar retrieved two extra studies. Screening reference lists yielded four extra studies, while contact with experts yielded another, unpublished study. An additional study was identified through the peer‐review process. After screening abstracts for eligibility, 23 studies were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Full text articles of seemingly relevant studies were obtained. Seven studies had insufficient information to be classified (Accinelli 1978; Ahmed 1982; Georges 2007; Rajani 2011; Ranka 2002; Recto 1997; Roy 2007), for more details, see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. We contacted the study authors if a contact address was available to obtain additional information but none of the authors responded. One study was listed in the IRCT register and has not been published (Movahed 2010, see Characteristics of ongoing studies). We included one unpublished study (Mukaindo 2010) and 18 published studies (14 full texts, three conference abstracts and one letter to the editor), including 2798 participants, in the review (Table 1). Fifteen studies were included in the meta‐analysis. For a summary of the search results, see Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram ‐ September 2011 search

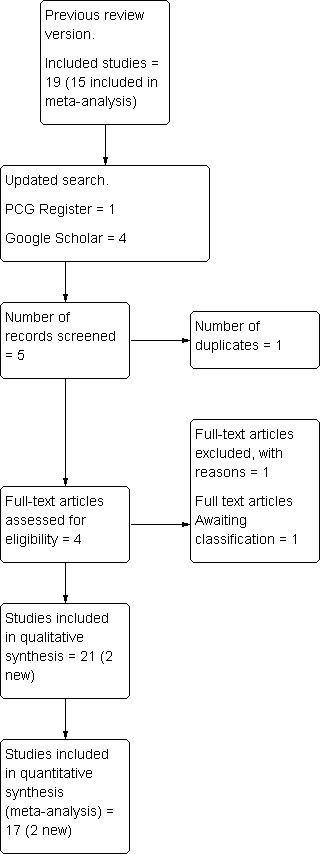

February 2013 search

This updated search retrieved one report from the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Register and four from Google Scholar. After removing one duplicate study, we assessed full text of four. We excluded Fouedjio 2012 and included Dahal 2013 and Sekhavat 2012. Zagami 2012 is awaiting translation (see Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram ‐ February 2013 search

Included studies

Twenty‐one studies were included in this updated review of which 17 were included in the meta‐analysis. See Characteristics of included studies.

Study location

Nine of the studies were conducted in India (Ajmera 2006; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003); three in Iran (Azari 2010; Sekhavat 2012, Makvandi 2010); two in Turkey (Batukan 2006; Yilmaz 2009); two in Saudi Arabia (Al Matari 2007; Al Qahtani 2011); and one each in Jamaica (Samuels 2007); the USA (Taskin 1993); Kenya (Mukaindo 2010), Italy (Cromi 2011) and Nepal (Dahal 2013). All the studies took place in a hospital setting, mostly a tertiary or teaching hospital.

Types of antispasmodics/interventions

The antispasmodics used in the intervention groups were valethamate bromide (Ajmera 2006; Batukan 2006; Dahal 2013; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001; Taskin 1993; Yilmaz 2009), drotaverine hydrochloride (Ajmera 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004), hyoscine butyl bromide ( Al Matari 2007; Al Qahtani 2011; Gupta 2008; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Raghavan 2008; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Taskin 1993), rociverine (Cromi 2011) and camylofin dihydrochloride (Warke 2003). One study used a combination of hyoscine and atropine (Azari 2010).

Drotaverine hydrochloride, rociverine and camylofin dihydrochloride are musculotropic agents ‐ phosphodiesterase type IV inhibitors, structurally related to papaverine. They have mild Ca‐channel blocking effects, no anticholinergic effects and act directly on smooth muscle cells, inhibiting spasm (Romics 2003; Sommers 2002). Valethamate bromide and hyoscine butyl bromide (Buscopan) are anticholinergic agents, which act as antagonists of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors, inhibiting muscle spasm of smooth muscles innervated by the parasympathetic nerves (Samuels 2009; Sommers 2002).

NIne of the studies were multi‐intervention studies (Ajmera 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001; Taskin 1993; Yilmaz 2009), all with two or more intervention groups and one control group. Two multi‐intervention studies (Taskin 1993; Yilmaz 2009) had one intervention arm of meperidine, which is not classified as an antispasmodic and was therefore not included in the meta‐analysis. The other intervention arms of these two studies, valethamate bromide and hyoscine butyl bromide, were used for analysis. The other seven multi‐intervention studies (Ajmera 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001) included two different antispasmodic agents in the intervention groups and a control group. All three groups were included in the meta‐analyses.

Antispasmodic drugs were administered intravenously (IV), intramuscularly (IM) or per rectum (PR). Hyoscine butyl bromide was administered IV or PR, while drotaverine hydrochloride was only administered IM. Valethamate bromide was administered either IV or IM. Rociverine as well as camylofin dihydrochloride were administered IM.

Fourteen studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004; Taskin 1993; Yilmaz 2009) followed a protocol for active management of labour, which included artificial rupture of membranes (aROM), augmentation with oxytocin, or both. Two studies ( Sharma 2001; Warke 2003) avoided aROM and did not augment labour with oxytocin. Five studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Khosla 2003; Raghavan 2008) did not mention aROM or oxytocin.

Participants

Ten studies included only primigravid women (Al Qahtani 2011; Azari 2010; Cromi 2011; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009). Nine studies included both primi‐ and multigravid women (Ajmera 2006; Batukan 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Samuels 2007; Taskin 1993), the ratio of both not being statistically different in all the studies. Sekhavat 2012 only included multigravid women and Al Matari 2007 did not specify the gravidity of participants. Yilmaz 2009 included only women with induction of labour. Batukan 2006 and Dahal 2013 included women with induction of labour and women in spontaneous labour. Thirteen studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Qahtani 2011; Cromi 2011; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Raghavan 2008; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003) only included participants in spontaneous labour. Five studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Gupta 2008; Kuruvila 1992; Taskin 1993) did not specify whether participants were in spontaneous or induced labour.

Gupta 2008 included women with high‐risk pregnancies as well as women with low‐risk pregnancies. The rest of the studies only included women with low‐risk pregnancies.

Outcomes

For 17 studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Matari 2007; Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Raghavan 2008; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009), the primary outcome was the duration of labour. This included duration of first stage of labour (active stage of labour, from 3 cm to 4 cm to full cervical dilatation), second stage of labour (from full cervical dilatation to expulsion of baby), third stage of labour (from delivery of baby to delivery of placenta) and total duration of labour.

Ten studies (Ajmera 2006; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Yilmaz 2009), excluded participants delivering via caesarean section from their calculation of the mean duration of labour, while seven studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Dahal 2013; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Warke 2003) included participants undergoing caesarean section in the calculation of the mean duration of labour.

For three studies (Azari 2010; Cromi 2011; Kuruvila 1992), the primary outcome was rate of cervical dilatation. Singh 2004 reported on pain relief during labour. Taskin 1993 was only reported as an abstract and contains minimal information about methods, outcomes and results.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐four studies (Aggarwal 2008; Akleh 2010; Baracho 1982; Bhattacharaya 1984; Chan 1963; De Nobrega‐Correa 2010; Demory 1990; Fouedjio 2012; Guerresi 1981; Hamann 1972; Hao 2004; Kauppila 1970; Kaur 2003; Kaur 2006; Malensek 1985; Manpreet 2008; Maritati 1986; Mishra 2002; Mortazavi 2004; Rajkumar 2006; Sirohiwal 2005; Tabassum 2005; Tripti 2009; Von Hagen 1965) were excluded from the review. Reasons for exclusion were lack of randomisation, absence of a control group and inclusion of non‐eligible participants. These are summarised in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

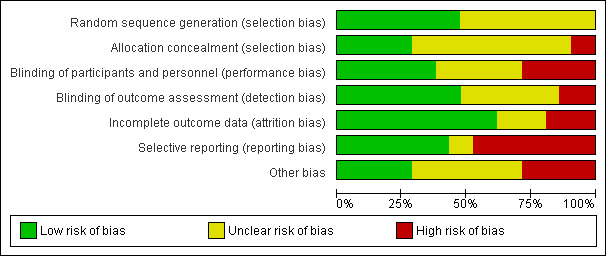

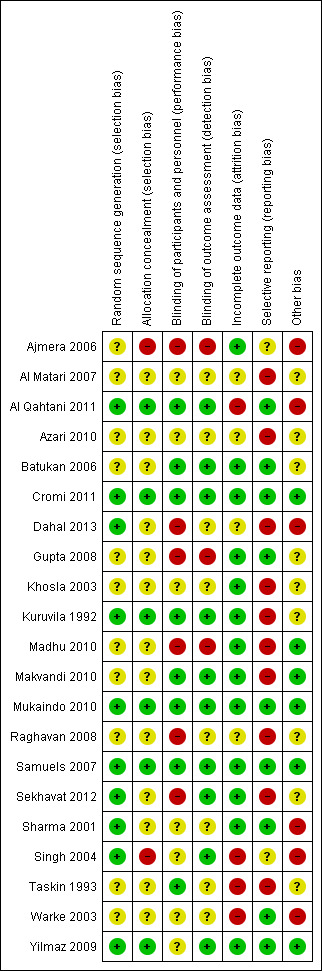

The risk of bias for each study is presented in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies table. Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the summary of risk of bias in all the studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Allocation sequence generation was assessed as adequate in 10 studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Cromi 2011; Dahal 2013; Kuruvila 1992; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Yilmaz 2009). Of these, seven (Cromi 2011; Dahal 2013; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Yilmaz 2009), used computer‐generated tables of random numbers; Kuruvila 1992 used a table of random numbers and two studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Singh 2004) drew paper slips from a box. Sequence generation was unclear in the remaining 11 studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Batukan 2006; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Raghavan 2008; Taskin 1993; Warke 2003).

Only six studies reported adequate allocation concealment (Al Qahtani 2011; Cromi 2011; Kuruvila 1992; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009). Samuels 2007 and Mukaindo 2010 used sequentially numbered, pre‐filled syringes, Kuruvila 1992 used identical, sequentially numbered ampoules and Yilmaz 2009 used sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes to conceal allocation. Cromi 2011 used an independent resident physician who managed the randomisation process and drew up the injectable in a separate pharmacy room in the labour ward, while Al Qahtani 2011 used the nurse in charge to draw an envelope from a box and prepare the injectable accordingly. In Batukan 2006, it was unclear whether sealed envelopes were opaque and sequentially numbered, in Makvandi 2010 it was unclear whether suppositories were in identical packages and sequentially numbered, while in Ajmera 2006 and Singh 2004, allocation concealment was evidently absent. Allocation concealment was not reported in the rest of the studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Taskin 1993; Warke 2003).

Blinding

Eight studies had low risk of performance bias and adequately reported on blinding of participants and personnel (Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Kuruvila 1992; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Taskin 1993). In Yilmaz 2009, participants were blinded, but nurses were not blinded. In six studies (Ajmera 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sekhavat 2012), blinding of participants and personnel was absent. In the remaining seven studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Khosla 2003; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003), it was unclear whether blinding of participants and personnel occurred due to poor reporting.

Ten studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Kuruvila 1992; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004; Yilmaz 2009) had low risk of detection bias and adequately reported on blinding of outcome assessors. Three studies (Ajmera 2006; Gupta 2008; Madhu 2010) did not blind outcome assessors and were considered to have a high risk of detection bias. The remaining studies ( Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Dahal 2013; Khosla 2003; Raghavan 2008; Sharma 2001; Taskin 1993; Warke 2003) were judged as unclear risk of detection bias, due to poor reporting of blinding of outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies (Al Qahtani 2011; Singh 2004; Taskin 1993; Warke 2003) failed to adequately report on the outcomes of all the participants and were considered to have a high risk for attrition bias. Two studies (Singh 2004; Taskin 1993) did not report separate loss to follow‐up figures for control and intervention groups, while Warke 2003 did not report on the details of participant outcomes and the percentages did not add up. Al Qahtani 2011 did not report outcomes for 13 participants who were randomised to intervention and control groups, had received the corresponding treatment but were excluded from the analysis due to various reasons. Four studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Dahal 2013; Raghavan 2008) could not be classified as high or low risk of attrition bias. Azari 2010 and Raghavan 2008 only reported the number of participants enrolled in the study; while in Al Matari 2007 it was unclear whether or not women who did not deliver after four hours were included in the analysis. Dahal 2013 did not report the number of participants with the results. The remaining studies (Ajmera 2006; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Yilmaz 2009) reported adequately on all participants.

Selective reporting

Nine studies reported adequately on outcomes (Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Gupta 2008; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sharma 2001; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009). Ten studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Dahal 2013; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Raghavan 2008; Sekhavat 2012; Taskin 1993) were considered as having a high risk of reporting bias. Three of these studies (Azari 2010; Madhu 2010; Raghavan 2008), did not report on all the outcomes pre‐specified in the study report, Makvandi 2010 did not report on the primary outcomes as specified in the study protocol; while the rest (Al Matari 2007; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Taskin 1993), did not pre‐specify which outcomes were being assessed in the methodology. In three studies (Ajmera 2006; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004), secondary outcomes were not clearly reported and Dahal 2013 omitted results of the control group for certain outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

Six studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Qahtani 2011; Dahal 2013; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003) had a high potential for other bias. Sharma 2001 reported a 100% rate of normal vertex deliveries (NVDs) although the hospital's normal rate of caesarean section is 12%, raising doubt about the validity of the study. Singh 2004 started the intervention at 3 cm to 6 cm cervical dilatation, but had more participants in the intervention group with 6 cm cervical dilatation than in the control group (18 versus three). In Al Qahtani 2011 , there was a significant baseline imbalance between groups regarding rupture of membranes at enrolment and Dahal 2013 failed to report on baseline characteristics of participants and had different results for the outcomes "duration of active phase of labour" and "duration of labour until the end of first stage of labour", although these are essentially the same. In nine studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Batukan 2006; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Raghavan 2008; Sekhavat 2012; Taskin 1993) it was unclear if any other bias was introduced. Three studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Taskin 1993) were only reported as conference abstracts and lack detail and contact information, while Raghavan 2008 was reported as a letter to the editor and also lacks details and contact information. Data extraction of Batukan 2006 was carried out by a translator and judgement about other biases was therefore difficult. Gupta 2008 did not have the same starting point for all participants, but reported that this was not significantly different between treatment and intervention groups and Sekhavat 2012 did not specify which outcome was used to calculate the sample size and included only multigravid women in their study. Six studies (Cromi 2011; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009) were assessed as being free of other bias.

Bias introduced by drug company sponsorship was evidently absent in eight studies ( Al Qahtani 2011; Cromi 2011; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009). In the remaining 13 studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Batukan 2006; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Raghavan 2008; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Taskin 1993), it was unclear whether drug company sponsorship was present, since conflict of interest was not explicitly mentioned.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

A summary of the effects of the interventions is presented in Table 2.

1. Summary of included studies.

| Study | Country | Number of participants | Low‐/high‐risk pregnancy | Gravidity of participants | Time of intervention | Intervention (dose and route of administration) | Control | Non‐study interventions | Induced/spontaneous labour |

| Ajmera 2006 | India | 225 | Low risk | Primi‐and multigravidas | Active phase, 3 cm dilatation | Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI¹) Valethamate bromide (8 mg IVI²) |

No medication | None specified | Spontaneous |

| Al Matari 2007 | Saudi Arabia | 199 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Hyoscine‐N‐butyl bromide (not mentioned) | Placebo (not specified) | None specified | Not mentioned |

| Al Qahtani 2011 | Saudi Arabia | 110 | Low risk | Primigravidas | Established labour, 3‐4 cm dilatation | Hyoscine butyl bromide (40 mg IMI) | NaCl³ 0.9% (2 mL IMI) | Amniotomy, opioid analgesia | Spontaneous |

| Azari 2010 | Iran | 200 | Not mentioned | Primigravidas | 4 cm dilatation and ruptured membranes | Hyoscine and atropine (20 mg IVI) | Dextrose water (2 cc IVI) | Not specified | Not mentioned |

| Batukan 2006 | Turkey | 100 | Low risk | Primi‐and multigravida | 4‐5 cm dilatation | Valethamate bromide (8 mg IMI) | NaCl 0.9% (1 mL IVI) | Oxytocin if necessary, amniotomy if no spontaneous ROM⁴ at 8‐10 cm | Spontaneous and induced |

| Cromi 2011 | Italy | 120 | Low risk | Primigravida | 3‐5 cm dilatation | Rociverine (20 mg IMI) | NaCl 0.9% (2 mL IMI) | Amniotomy, augmentation with oxytocin, epidural analgesia | Spontaneous |

| Dahal 2013 | Nepal | 300 | Low risk | Primi‐ and multigravidas | Unclear | Valethamate bromide (8mg IMI) Drotaverine hydrochloride (40mg IMI) |

No medication | Amniotomy once cervical dilatation > 4cm, or if Bishop's score was favourable, oxytocin augmentation | Spontaneous and induced |

| Gupta 2008 | India | 150 | Low and high risk | Primi‐and multigravidas | 3 cm dilatation | Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI) Hyoscine butyl bromide (20 mg IVI) |

No medication | Oxytocin if necessary, amniotomy | Not specified |

| Khosla 2003 | India | 300 | Low risk | Primi‐and multigravidas | 4 cm dilatation | Valethamate bromide (8 mg IMI) Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI) |

No medication | Not specified | Spontaneous |

| Kuruvila 1992 | India | 120 | Low risk | Primi‐ and multigravidas | 2‐4 cm | Valethamate bromide (8 mg IMI) | NaCl 0.9% (1 mL IMI) | Oxytocin if necessary, amniotomy, pethidine 75 mg for primigravidas) | Not specified |

| Madhu 2010 | India | 150 | Low risk | Primi‐and multigravida | 4 cm dilatation | Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI) Valethamate bromide (8 mg IMI) |

NaCl 0.9% (2 mL IMI) | Amniotomy, oxytocin if required, paracetamol and pethidine for labour analgesia | Spontaneous |

| Makvandi 2010 | Iran | 130 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 3‐4 cm dilatation | Hyoscine butyl bromide (20 mg PR⁵) | Placebo suppository | Amniotomy when presenting part was fixed | Spontaneous |

| Mukaindo 2010 | Kenia | 85 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 3‐6 cm dilatation | Hyoscine butyl bromide (40 mg IVI) | Sterile water (2 mL IVI) | Amniotomy and augmentation with oxytocin as per protocol | Spontaneous |

| Raghavan 2008 | India | 150 | Not mentioned | Primigravidas | Not mentioned | Hyoscine butyl bromide (PR) Valethamate bromide (IVI) |

No medication | Not specified | Spontaneous |

| Samuels 2007 | Jamaica | 129 | Low risk | Primi‐ and multigravidas | 4‐5 cm dilatation | Hyoscine butyl bromide (20 mg IVI) | NaCl 0.9% (1 mL IVI) | Routine amniotomy, opioid analgesia, oxytocin | Spontaneous |

| Sekhavat 2012 | Iran | 188 | Low risk | Multigravidas | 3‐4 cm dilatation | Hyoscine butyl bromide (20 mg IVI) | NaCl 0.9% (1 mL IVI) | Amniotomy, oxytocin | Spontaneous |

| Sharma 2001 | India | 150 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 4 cm dilatation | Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI) Valethamate bromide (8 mg IMI) |

No medication | None | Spontaneous |

| Singh 2004 | India | 100 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 3‐6 cm dilatation | Drotaverine hydrochloride (40 mg IMI) | Distilled water 2 mL (IMI) | Amniotomy, oxytocin, pentazocine and promethazine, episiotomy | Spontaneous |

| Taskin 1993 | USA | 120 | Low risk | Primi‐and multigravidas | 4‐5 cm dilatation | Valethamate bromide (8 mg IVI) Hyoscine bromide (20 mg IVI) Meperidine (50 mg IVI) |

Placebo (not specified, IVI) | Not specified | Not mentioned |

| Warke 2003 | India | 100 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 3 cm dilatation | Camylofin dihydrochloride (50 mg IMI) | Placebo (not specified (IMI) | None | Spontaneous |

| Yilmaz 2009 | Turkey | 160 | Low risk | Primigravidas | 4‐6 cm dilatation | Valethamate bromide (16 mg IVI) Meperidine (50 mg IVI) |

NaCl 0.9% (10 mL) | Amniotomy, oxytocin, episiotomy | Induced only |

¹IVI: intravenous injection

²IMI: intramuscular injection

³NaCl: sodium chloride/saline

⁴ROM: rupture of membranes

⁵PR: per rectum

Although this review included 21 studies (3286 participants), only 17 studies (2617 participants) were included in the meta‐analysis. Four studies (Al Matari 2007; Azari 2010; Raghavan 2008; Taskin 1993) were not included in the meta‐analysis because they were only reported as abstracts and contained insufficient information on relevant data. In addition, they did not contain contact information of authors to obtain missing data.

Primary outcomes

1. Duration of labour

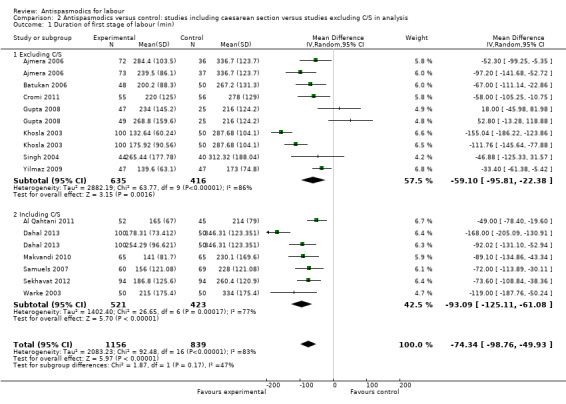

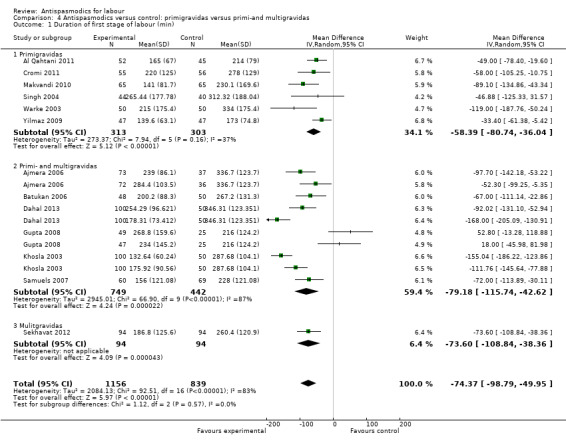

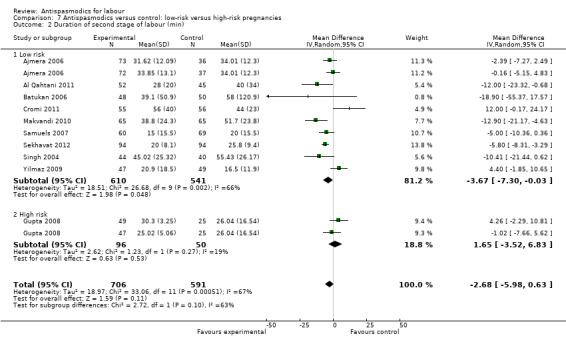

Duration of first stage of labour

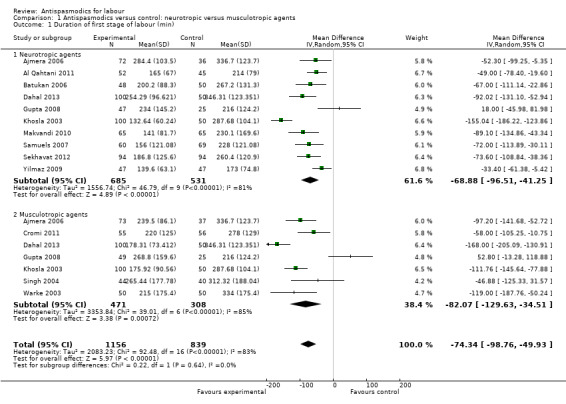

Thirteen studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Makvandi 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) involving 1995 women were included in the random‐effects meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.1). Antispasmodics reduced the duration of first stage of labour by an average of 74.34 minutes (mean difference (MD) ‐74.34 minutes; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐98.76 to ‐49.93; T² = 2083.23; I² = 83%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 1 Duration of first stage of labour (min).

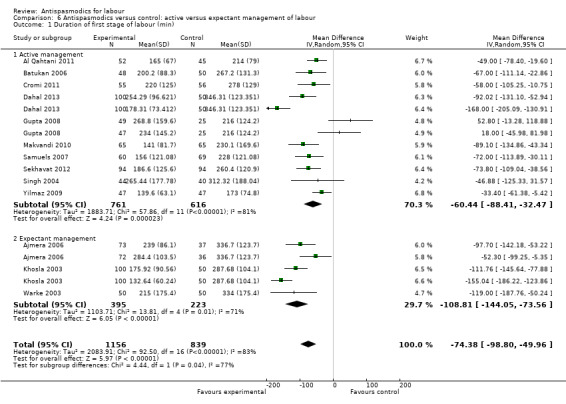

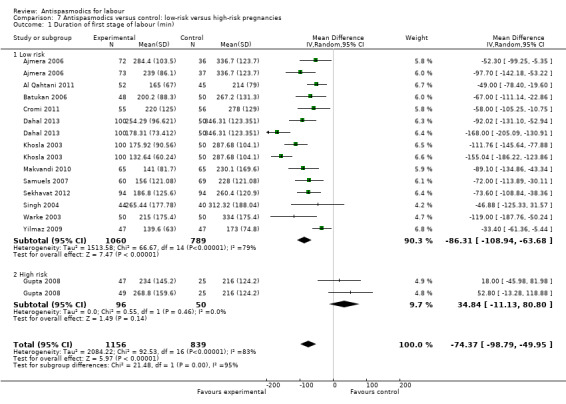

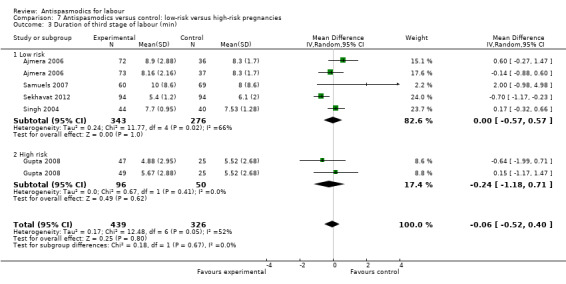

Subgroup analysis showed significant differences between subgroups for management of labour (active versus expectant management of labour) (Chi² = 4.44, P = 0.04, I² = 77.5%) (Analysis 6.1) and type of pregnancy (low‐ versus high‐risk pregnancy) (Chi² = 21.48, P < 0.00001, I² = 95.3%) (Analysis 7.1). There were no significant differences between the other subgroups.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Antispasmodics versus control: active versus expectant management of labour, Outcome 1 Duration of first stage of labour (min).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antispasmodics versus control: low‐risk versus high‐risk pregnancies, Outcome 1 Duration of first stage of labour (min).

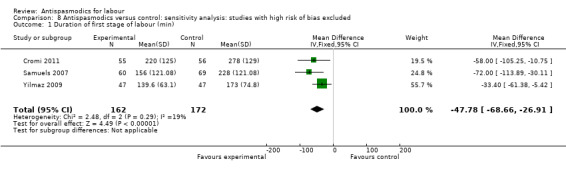

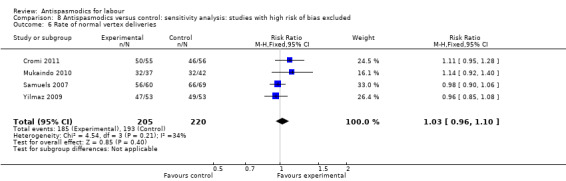

Sensitivity analysis, excluding studies with high risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data), included only three studies (Cromi 2011; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009; n = 334) and showed a smaller, yet still significant reduction in duration of first stage of labour (MD ‐47.78 minutes; 95% CI ‐68.66 to ‐26.91, fixed‐effect) with an absence of significant heterogeneity (Chi² = 2.48; P = 0.29; I² = 19%) (Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 1 Duration of first stage of labour (min).

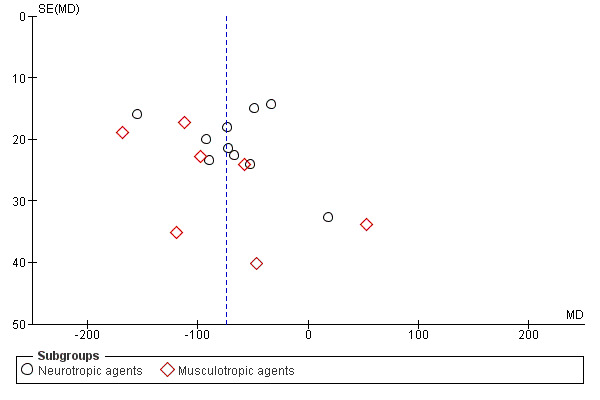

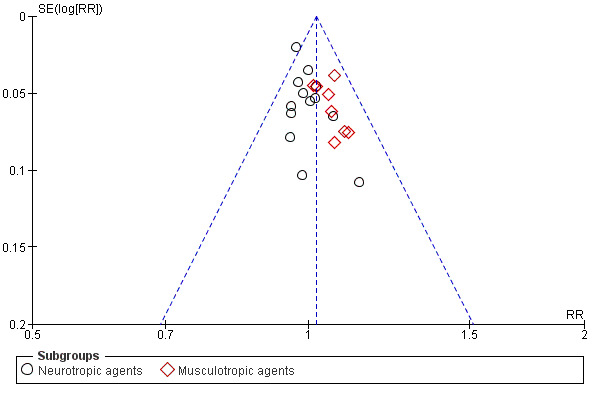

The funnel plot for this outcome was asymmetrical (Figure 5).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antispasmodics versus control, outcome: 1.1 Duration of first stage of labour (min).

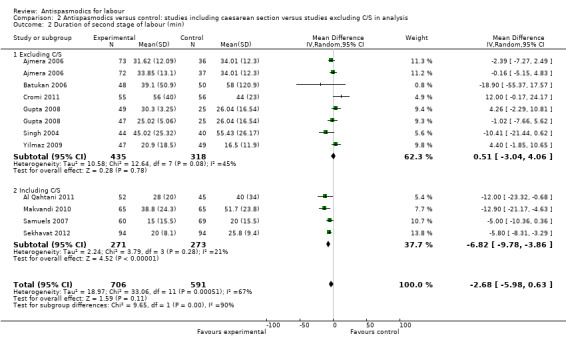

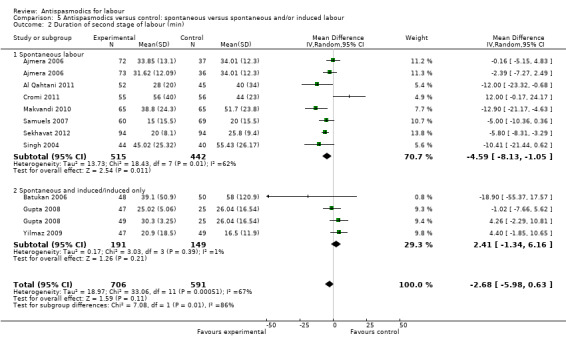

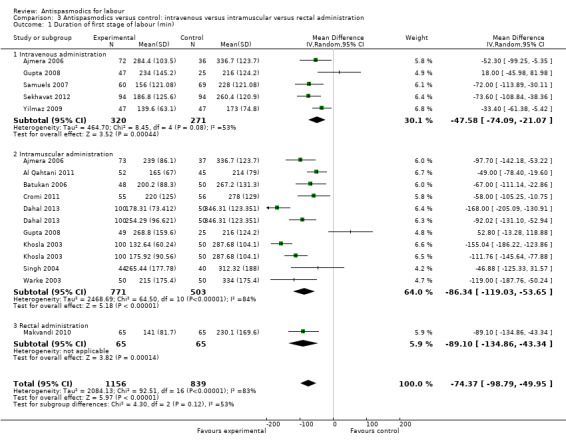

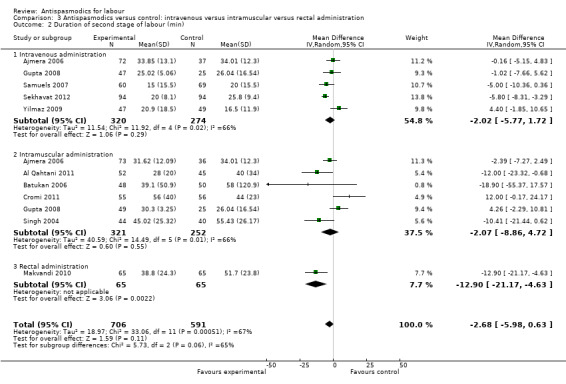

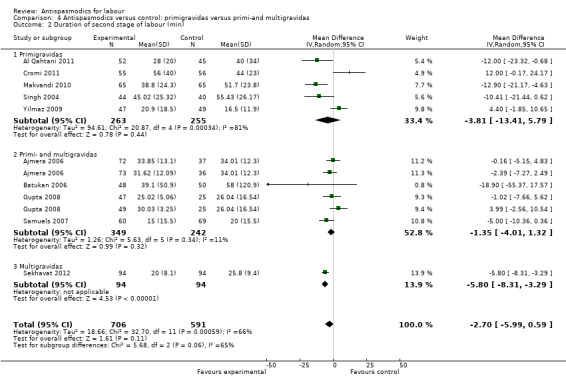

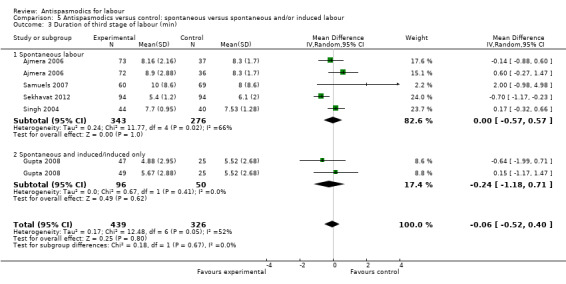

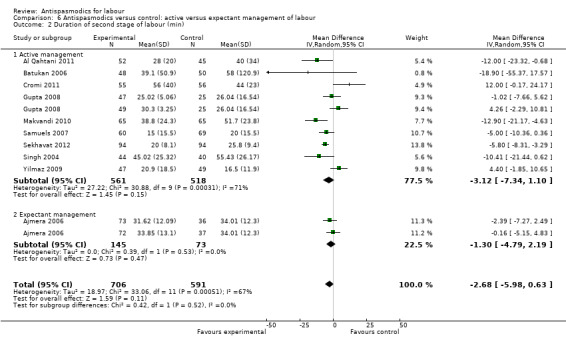

Duration of second stage of labour

Ten studies (involving 1297 women) (Ajmera 2006; Al Qahtani 2011; Batukan 2006; Cromi 2011; Gupta 2008; Makvandi 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004; Yilmaz 2009) were included in the random‐effects meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.2). There was no significant reduction in the duration of the second stage of labour, with an average intervention effect of ‐2.68 minutes (95% CI ‐5.98 to 0.63, T² = 18.97; I² = 67%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 2 Duration of second stage of labour (min).

Subgroup analysis showed significant differences between subgroups for studies excluding versus studies including caesarean sections in the analysis (Chi² = 9.65, P = 0.002, I² = 89.6%) (Analysis 2.2) and type of labour (spontaneous versus induced labour) (Chi² = 7.08, P = 0.008, I² = 85.9%) (Analysis 5.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antispasmodics versus control: studies including caesarean section versus studies excluding C/S in analysis, Outcome 2 Duration of second stage of labour (min).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antispasmodics versus control: spontaneous versus spontaneous and/or induced labour, Outcome 2 Duration of second stage of labour (min).

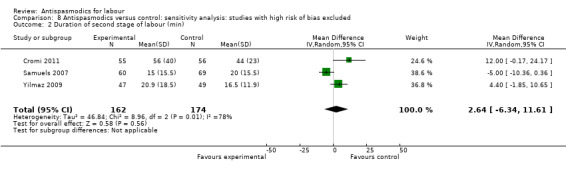

Sensitivity analysis included three studies (Cromi 2011; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009) (involving 336 women) and did not show a significantly different effect (MD 2.64 minutes; 95% CI ‐6.34 to 11.61; I² = 78%) (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 2 Duration of second stage of labour (min).

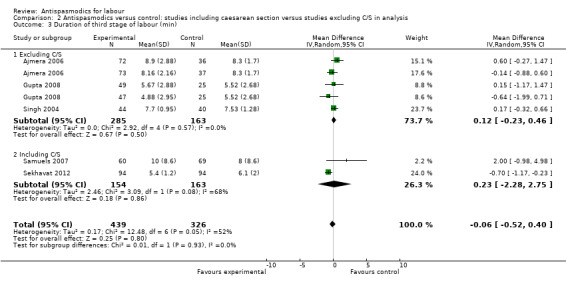

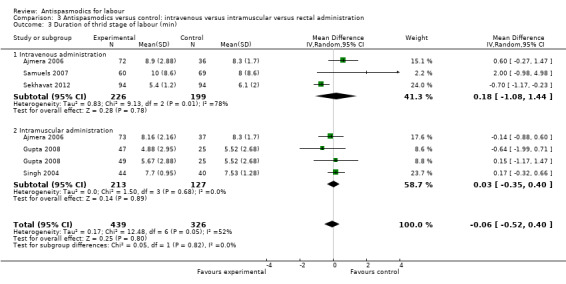

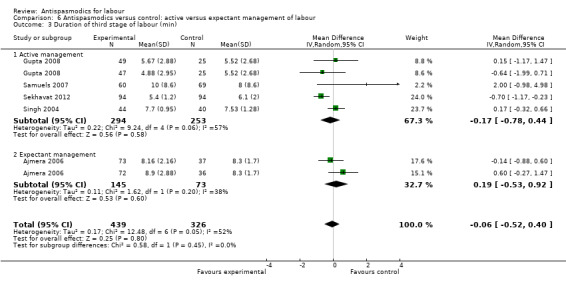

Duration of third stage of labour

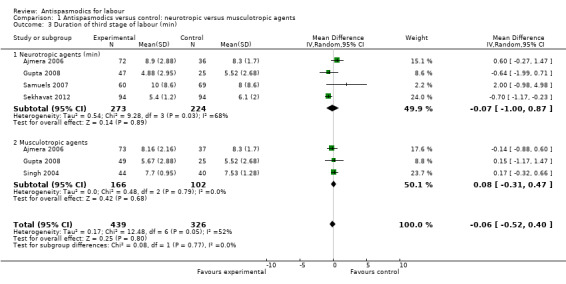

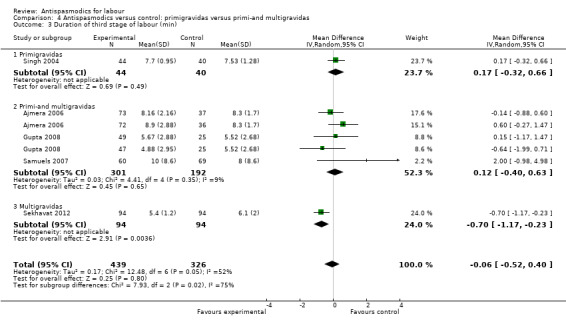

Five studies (involving 765 women) (Ajmera 2006; Gupta 2008; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Singh 2004) were included in the random‐effects meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.3). Overall, there was no significant effect of antispasmodics on the third stage of labour (MD ‐0.06 minutes; 95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.40; T² = 0.17; I² = 52%). Subgroup analysis showed a significant difference between groups for gravidity of women (primigravidas versus primi‐and multigravidas versus multigravidas) (Chi² = 7.93, P = 0.02, I² = 74.8%) (Analysis 4.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 3 Duration of third stage of labour (min).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Antispasmodics versus control: primigravidas versus primi‐and multigravidas, Outcome 3 Duration of third stage of labour (min).

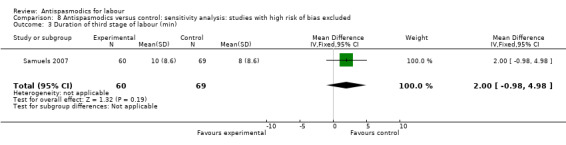

Sensitivity analysis only included the Samuels 2007 study and did not show a significant effect on the duration of third stage of labour (MD 2.00 minutes; 95% CI ‐0.98 to 4.98; one study, 129 women) (Analysis 8.3).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 3 Duration of third stage of labour (min).

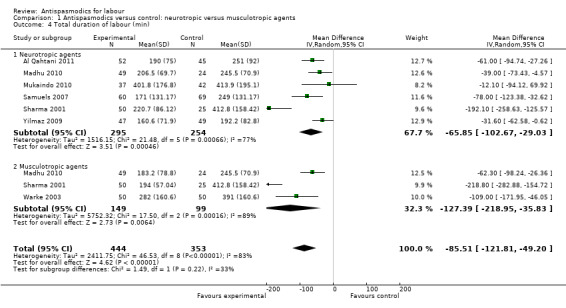

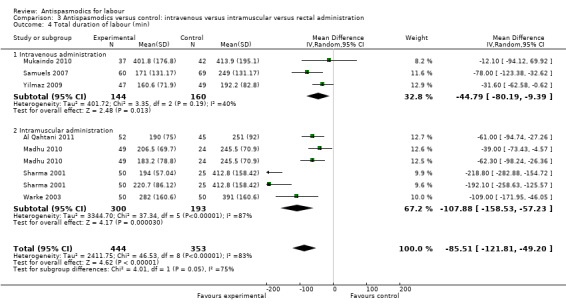

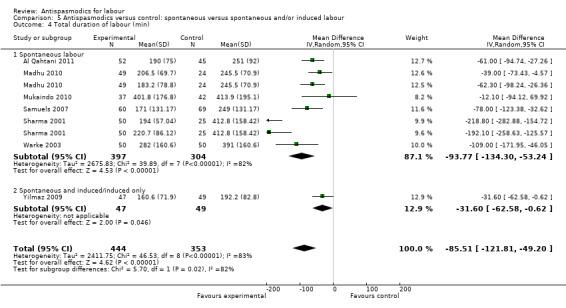

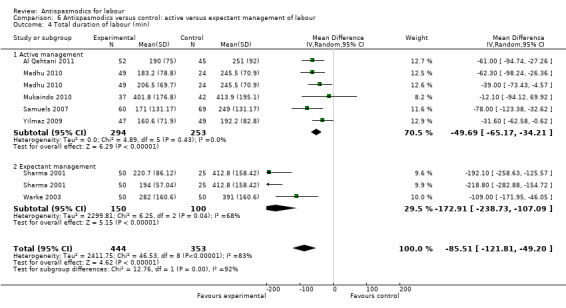

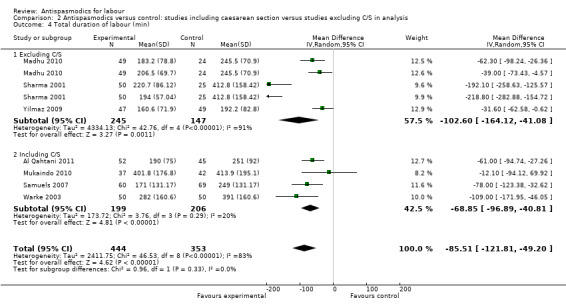

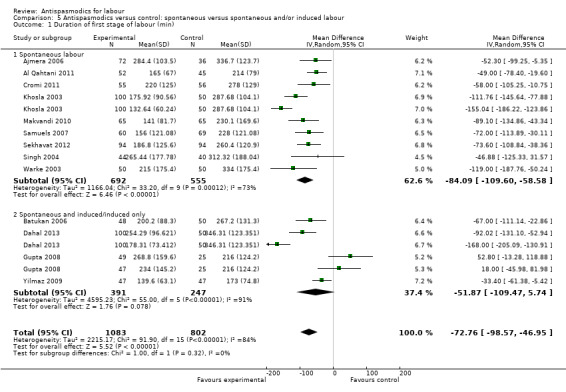

Total duration of labour

Seven studies (involving 797 women) (Al Qahtani 2011; Madhu 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sharma 2001; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) assessed this outcome. Random‐effects meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.4) showed an average reduction of 85 minutes in the total duration of labour, but significant heterogeneity was also present (MD ‐85.51; 95% CI ‐121.81 to ‐49.20; T² = 2411.75; I² = 83%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 4 Total duration of labour (min).

Subgroup analysis showed a significant difference between groups for route of administration (intravenous versus intramuscular administration) (Chi² = 4.01, P = 0.05, I² = 75.0%) (Analysis 3.4), type of labour (spontaneous versus induced labour) (Chi² = 5.70, P = 0.02, I² = 82.5%) (Analysis 5.4) and management of labour (active versus expectant management of labour) (Chi² = 12.76, P = 0.0004, I² = 92.2%) (Analysis 6.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antispasmodics versus control: intravenous versus intramuscular versus rectal administration, Outcome 4 Total duration of labour (min).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antispasmodics versus control: spontaneous versus spontaneous and/or induced labour, Outcome 4 Total duration of labour (min).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Antispasmodics versus control: active versus expectant management of labour, Outcome 4 Total duration of labour (min).

Sensitivity analysis included three studies (involving 304 women) (Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009) with adequate allocation concealment and without incomplete reporting of data. The results showed a smaller, but significant reduction in the total duration of labour (MD ‐44.79 minutes; 95% CI ‐80.19 to ‐9.39; random‐effects, T² = 401.72, I² = 40%) (Analysis 8.4). Heterogeneity was reduced considerably.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 4 Total duration of labour (min).

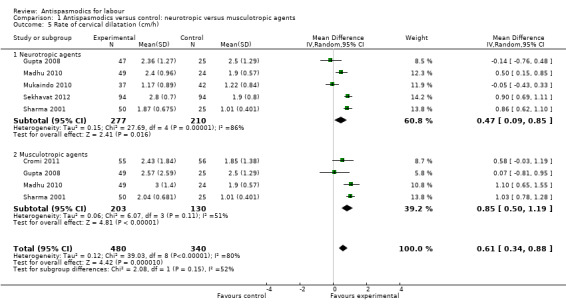

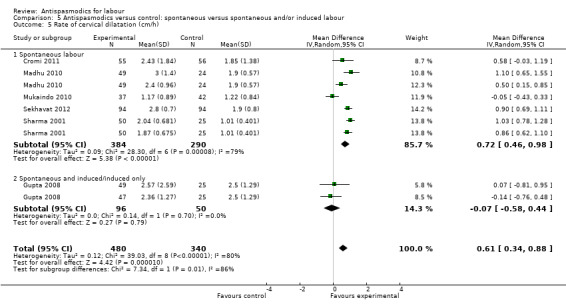

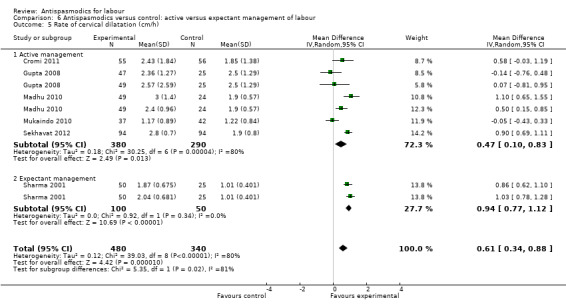

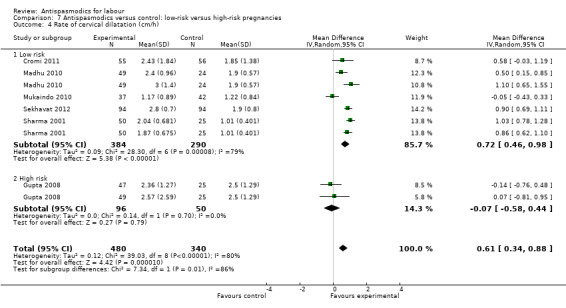

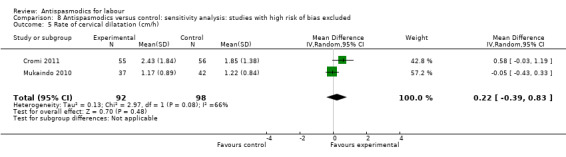

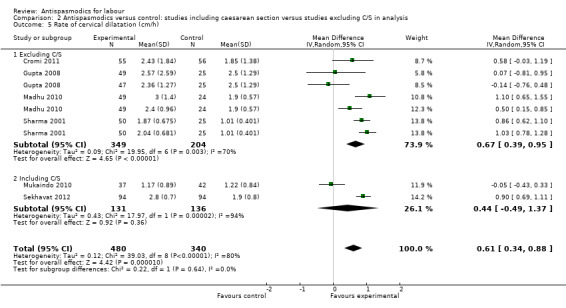

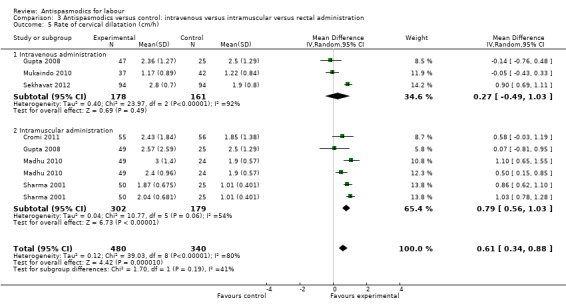

2. Rate of cervical dilatation

Seven studies (Cromi 2011; Gupta 2008; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001) reported on the cervical dilatation rate and six of these (involving 820 women) were included in the meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.5). Kuruvila 1992 reported data in four different subgroups and was not included. Random‐effects meta‐analysis showed a significant average increase in the rate of cervical dilatation of 0.61 cm/hour. Significant heterogeneity was observed (MD 0.61cm/hour; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.88; random‐effects, T² = 0.12; I² = 80%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 5 Rate of cervical dilatation (cm/h).

Subgroup analysis showed a significant difference for type of labour (spontaneous versus induced labour) (Chi² = 7.34, P = 0.007, I² = 86.4%) (Analysis 5.5), management of labour (active versus expectant management of labour) (Chi² = 5.35, P = 0.02, I² = 81.3%) (Analysis 6.5) and type of pregnancy (low‐ versus high‐risk pregnancy) (Chi² = 7.34, P = 0.007, I² = 86.4%) (Analysis 7.4).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Antispasmodics versus control: spontaneous versus spontaneous and/or induced labour, Outcome 5 Rate of cervical dilatation (cm/h).

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Antispasmodics versus control: active versus expectant management of labour, Outcome 5 Rate of cervical dilatation (cm/h).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antispasmodics versus control: low‐risk versus high‐risk pregnancies, Outcome 4 Rate of cervical dilatation (cm/h).

Sensitivity analysis only included two studies (involving 190 women) (Cromi 2011; Mukaindo 2010) and showed a non‐significant effect of antispasmodics on the rate of cervical dilatation (MD 0.22 cm/hour; 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.83; I² = 66%) (Analysis 8.5).

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 5 Rate of cervical dilatation (cm/h).

3. Pain relief

Only one study (Singh 2004) assessed the effect of antispasmodics on pain relief (n = 100), by using both a visual analogue scale (VAS) with a zero to 100 score, and a verbal rating scale from zero to four. Pain was assessed hourly. There was a similar trend in the experience of pain in both groups. During the second stage, the intervention group had more pain than the placebo group, but in the fourth stage, the intervention group had less pain. Three participants asked for pain relief in the intervention group, compared with two in the control group. The effect of the intervention was thus not significant.

4. Rate of normal vertex deliveries (NVDs)

Sixteen studies (Ajmera 2006; Al Qahtani 2011; Cromi 2011; Dahal 2013; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Kuruvila 1992; Madhu 2010; Makvandi 2010; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Sekhavat 2012; Sharma 2001; Singh 2004; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) (involving 2319 women) were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis on rate of normal vertex deliveries (Analysis 1.6). Antispasmodics had no overall significant effect on the rate of normal vertex deliveries (risk ratio (RR) 1.02, 95% CI 1.00, 1.05). Subgroup analysis, however, showed a significant difference between groups for type of antispasmodic (neurotropic versus musculotropic) (Chi² = 4.97, P = 0.03, I² = 79.9%) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antispasmodics versus control: neurotropic versus musculotropic agents, Outcome 6 Rate of normal vertex deliveries.

Sensitivity analysis included four studies (involving 425 women) (Cromi 2011; Mukaindo 2010; Samuels 2007; Yilmaz 2009) with low risk of bias and did not show a difference in effect (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.10; I² = 34%) (Analysis 8.6).

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antispasmodics versus control: sensitivity analysis: studies with high risk of bias excluded, Outcome 6 Rate of normal vertex deliveries.

The funnel plot for this outcome was symmetrical (Figure 6).

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antispasmodics versus control, outcome: 1.6 Rate of NVDs.

Secondary outcomes

1. Maternal adverse events

Maternal adverse events were reported using different approaches and are summarised in Table 3. Adverse events that were reported across studies were tachycardia, mouth dryness, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, giddiness, cervical laceration, flushing of face and postpartum haemorrhage. Meta‐analysis was conducted for outcomes reported quantitatively.

2. Maternal adverse events.

| Study | Tachycardia | Mouth dryness | Nausea | Vomiting | Dizziness | Cervical laceration | Giddiness | Blood loss | Flushing of face | Headache |

|

Ajmera 2006 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

2.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3% | 1.3% | Not reported | 0 | 4% |

|

Ajmera 2006 (Valethamtate bromide) |

14.6% | 2.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported | 5.3% | 2.7% |

|

Ajmera 2006 (Placebo) |

5.3% | 1.3% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4% | 4% | Not reported | 0 | 2.7% |

| Al Matari 2007 | Did not report on maternal adverse events | |||||||||

|

Al Qahtani 2011 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

PPH¹: 0/52; Tear: 2/50 | |||||||||

|

Al Qahtani 2011 (Placebo) |

PPH: 0/45; Tear: 0/45 | |||||||||

| Azari 2010 | Did not report on maternal adverse events | |||||||||

| Batukan 2006 | Women receiving Valethamate bromide experienced more dizziness and mouth dryness than women receiving placebo | |||||||||

|

Cromi 2011 (Rociverine) |

No maternal side effects reported | 300 mL (100‐1400) | ||||||||

|

Cromi 2011 (Placebo) |

No maternal side effects reported | 350 mL (50‐2000) | ||||||||

| Dahal 2013 | Dryness of mouth, vomiting, tachycardia and retention of urine were more pronounced in the valethamate bromide group than in the drotaverine hydrochloride and control groups | |||||||||

|

Gupta 2008 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

20% of participants experienced adverse events, the main ones being nausea and vomiting | |||||||||

|

Gupta 2008 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

10% | 0 | Main complaint | Main complaint | 24% of participants experienced adverse effects | |||||

|

Gupta 2008 (Placebo) |

No reported maternal adverse events | |||||||||

|

Khosla 2003 (Valethamate bromide) |

16% | 4% | Not reported | 4% | Not reported | |||||

|

Khosla 2003 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

No maternal adverse events reported | |||||||||

|

Khosla 2003 (Control) |

No maternal adverse events reported | |||||||||

| Kuruvila 1992 | Maternal pulse rate > 110/min observed in significantly more women receiving Valethamate bromide. Flushing of face and dryness of mouth not statistically significant between groups. | |||||||||

|

Madhu 2010 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10% |

|

Madhu 2010 (Valethamate bromide) |

81.6% | 20% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10% | 2% |

|

Madhu 2010 (Control) |

6.30% | 4.2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Makvandi 2010 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

Mean heart rate:83.34 beats/min, SD:10.56 Mean systolic BP: 108.78 mmHg, SD: 12.34 |

|||||||||

|

Makvandi 2010 (Placebo) |

Mean heart rate:86.65 beats/min, SD:12.87 Mean systolic BP: 110.09 mmHg, SD:13.67 |

|||||||||

|

Mukaindo 2010 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

1 patient reported transient palpitations PPH in 5.7% participants |

|||||||||

|

Mukaindo 2010 (Placebo) |

No adverse events reported PPH in 7.3% of participants |

|||||||||

|

Raghavan 2008 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

Mild tachycardia, dryness of mouth and vomiting | |||||||||

|

Raghavan 2008 (Valethamate bromide) |

Mild tachycardia, dryness of mouth and vomiting | |||||||||

|

Raghavan 2008 (No medication) |

No adverse events reported | |||||||||

|

Samuels 2007 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 150 mL (50‐1800 mL) | 0 | 0 |

|

Samuels 2007 (Placebo) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 150 mL (50‐550 mL) | 0 | 0 |

| Sekhavat 2012 | No adverse events reported | |||||||||

|

Sharma 2001 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4% |

|

Sharma 2001 (Valethamate bromide) |

20% | 10% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4% | 0 |

|

Sharma 2001 (Control) |

4% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6% | 0 | 0 | 4% |

|

Singh 2004 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

18% had atonic PPH | |||||||||

|

Singh 2004 (Control) |

2.5% had atonic PPH | |||||||||

|

Warke 2003 (Camylofin dihydrochloride) |

1% | 5% | 5% | 6% | 0 | 2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Warke 2003 (Control) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Yilmaz 2009 (Valethamte bromide) |

21.3% | 14.9% | 14.9% | 8.5% | 12.8% | 2.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Yilmaz 2009 (Control) |

4.1% | 0 | 10.2% | 6.1% | 4.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

¹PPH: postpartum haemorrhage

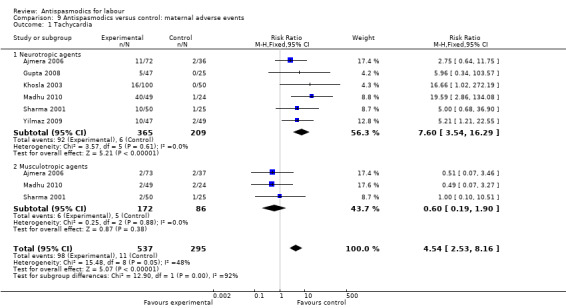

Tachycardia (Analysis 9.1)

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 1 Tachycardia.

Six studies (Ajmera 2006; Gupta 2008; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001; Yilmaz 2009) involving 832 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. There was an increased risk for tachycardia for participants receiving antispasmodics (RR 4.54; 95% CI 2.53 to 8.16). Subgroup analysis showed a significant difference between groups for type of antispasmodic (neurotropic versus musculotropic agents), with a greater risk with neurotropic agents (Chi² = 12.90,(P = 0.0003), I² = 92.3%).

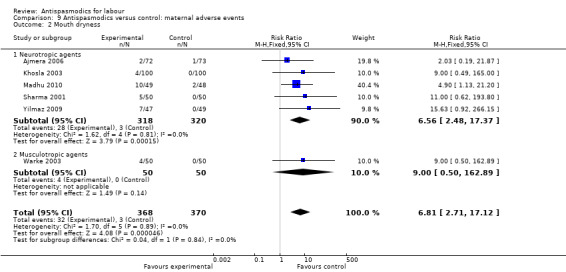

Mouth dryness (Analysis 9.2)

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 2 Mouth dryness.

Six studies (Ajmera 2006; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) involving 738 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. There was an increased risk for mouth dryness for participants receiving antispasmodics (RR 6.81; 95% CI 2.71 to 17.12).

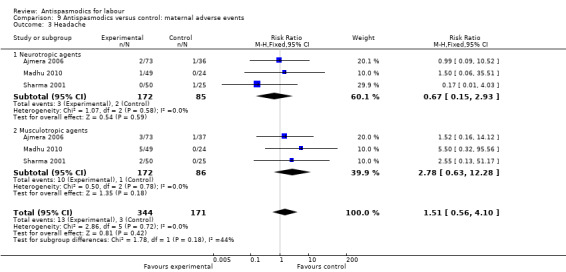

Headache (Analysis 9.3)

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 3 Headache.

Three studies (Ajmera 2006; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001) involving 515 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis.There was no significant difference in the risk for headaches between intervention and control groups (RR 1.51; 95% CI 0.56 to 4.10).

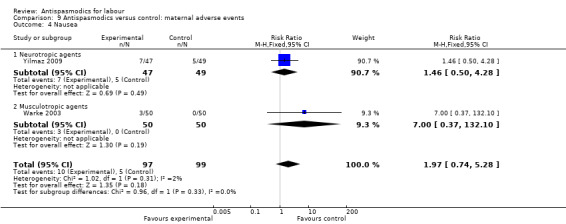

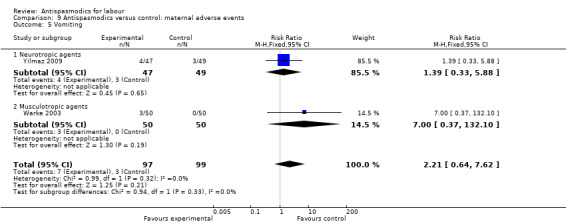

Nausea and vomiting (Analysis 9.4; Analysis 9.5)

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 4 Nausea.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

Two studies (Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) involving 196 women had quantitative data on nausea and on vomiting and were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, showing no significant difference in risk between intervention and control groups for either nausea (RR 1.97; 95% CI 0.74, 5.28) or vomiting (RR 2.21; 95% CI 0.64 to 7.62).

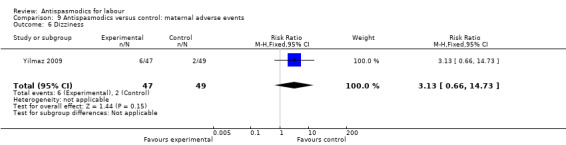

Dizziness (Analysis 9.6)

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 6 Dizziness.

Only one study (Yilmaz 2009) involving 96 women reported quantitative data on dizziness, showing no significant difference in risk for dizziness between intervention and control groups (RR 3.13; 95% CI 0.66 to 14.73).

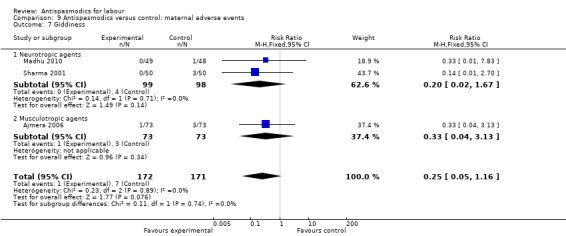

Giddiness (Analysis 9.7)

9.7. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 7 Giddiness.

Three studies (Ajmera 2006; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001) involving 343 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, showing no significant difference in risk for giddiness between intervention and control groups (RR 0.25; 95% CI 0.05 to 1.16).

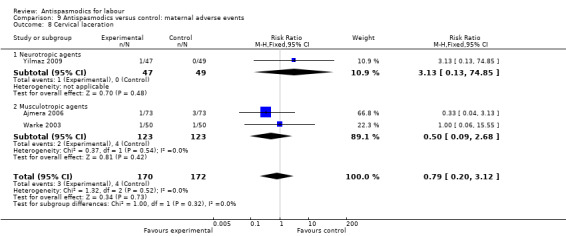

Cervical lacerations (Analysis 9.8)

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 8 Cervical laceration.

Three studies (Ajmera 2006; Warke 2003; Yilmaz 2009) including 342 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, showing no significant difference in risk for cervical lacerations between intervention and control groups (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.20 to 3.12).

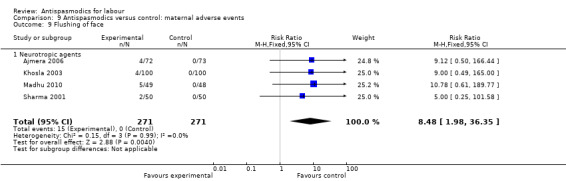

Flushing of face (Analysis 9.9)

9.9. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 9 Flushing of face.

Four studies (Ajmera 2006; Khosla 2003; Madhu 2010; Sharma 2001) involving 542 women were included in the fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, showing a significant increased risk for flushing of the face in the intervention group (RR 8.48; 95% CI 1.98 to 36.35).

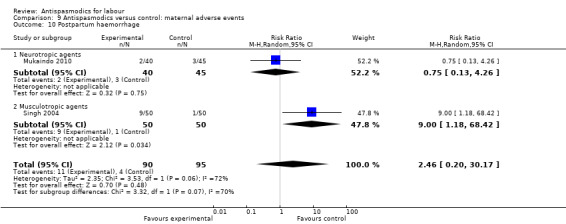

Postpartum haemorrhage (Analysis 9.10)

9.10. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antispasmodics versus control: maternal adverse events, Outcome 10 Postpartum haemorrhage.

Two studies (Mukaindo 2010; Singh 2004) involving 185 women, were included in the random‐effects meta‐analysis, showing no significant difference in risk for postpartum haemorrhage between intervention and control groups (RR 2.46; 95% CI 0.20 to 30.17;T² = 2.35; I² = 72%)

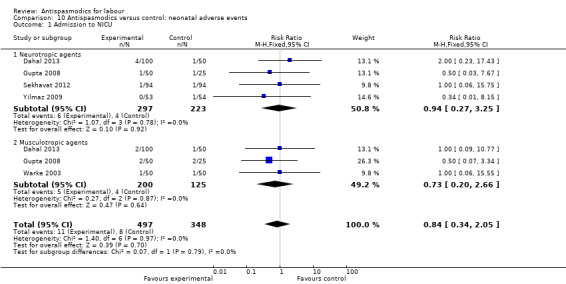

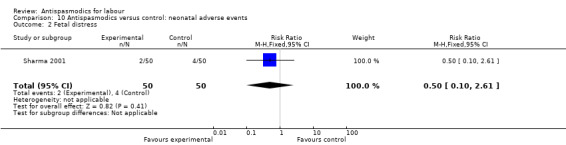

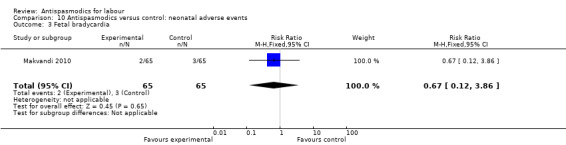

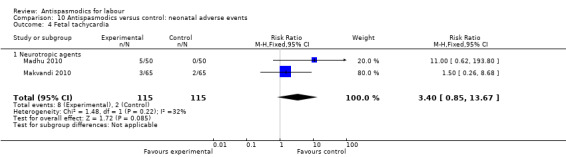

2. Neonatal adverse events

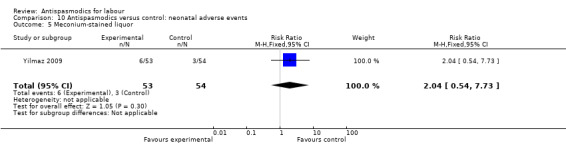

As with maternal adverse events, neonatal adverse events were reported using different approaches and are summarised in Table 4. Adverse events reported admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), fetal distress, fetal bradycardia, fetal tachycardia and presence of meconium‐stained liquor. Apgar scores at one and five minutes after delivery were also reported. A low Apgar score (less than seven at both one and five minutes) was also seen as an adverse event. Meta‐analysis was conducted for quantitatively reported outcomes.

3. Neonatal adverse events.

| Study | Apgar 1 min | Apgar 5 min | Meconium‐stained liquor | Fetal tachycardia | Fetal distress | Admission to NICU¹ | Need for resuscitation |

|

Ajmera 2006 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

No report on neonatal adverse events or Apgar scores | ||||||

|

Ajmera 2006 (Valethamate bromide) |

No report on neonatal adverse events or Apgar scores | ||||||

|

Ajmera 2006 (Control) |

No report on neonatal adverse events or Apgar scores | ||||||

|

Al Matari 2007 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

Mean score: 8.7 | Mean score: 9.4 | No other adverse events reported | ||||

|

Al Matari 2007 (Control) |

Mean score: 8.7 | Mean score: 9.3 | No other adverse events reported | ||||

|

Al Qahtani 2011 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

5/52 babies: score of 7‐8 |

Score: 8‐10 for all babies | No adverse events noted | ||||

|

Al Qahtani 2011 (Placebo) |

8/45 babies: score of 7‐8 |

Score: 8‐10 for all babies | No adverse events noted | ||||

| Azari 2010 | No reports of any neonatal adverse events | ||||||

| Batukan 2006 | No reported neonatal adverse events | ||||||

|

Cromi 2011 (Rociverine) |

Not reported | Score < 7: 0% | Arterial cord blood pH: 7.28 SD 0.11 | not reported | |||

|

Cromi 2011 (Placebo) |

Not reported | Score < 7: 1.8% | Arterial cord blood pH: 7.27 SD 0.08 | not reported | |||

|

Dahal 2013 (Valethamate bromide) |

Not reported | 4 | not reported | ||||

|

Dahal 2013 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

Not reported | 2 | not reported | ||||

|

Dahal 2013 (Control) |

Not reported | 2 | not reported | ||||

|

Gupta 2008 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

Mean score: 8 (7‐9) | Mean score: 9 (8‐9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | not reported |

|

Gupta 2008 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

Mean score: 8 (1‐9) | Mean score: 9 (3‐9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | not reported |

|

Gupta 2008 (Control) |

Mean score: 8 (4‐9) | Mean score: 9 (8‐9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | not reported |

| Khosla 2003 | "All babies had good Apgar scores and were discharged in good condition" | ||||||

| Kuruvila 1992 | No neonatal adverse events reported | ||||||

|

Madhu 2010 (Drotaverine hydrochloride) |

No report on neonatal adverse effects or Apgar scores | ||||||

|

Madhu 2010 (Valethamte bromide) |

Not reported | 10% | 0 | 0 | not reported | ||

|

Madhu 2010 (Control) |

No report on neonatal adverse effects or Apgar scores | ||||||

|

Makvandi 2010 (Hyoscine butyl bromide) |

Score < 7: 2 | Score < 7: 0 | Bradycardia: 3.10%; Tachycardia: 4.60% | not reported | |||

|

Makvandi 2010 (Control) |

Score < 7: 0 | Score < 7: 0 | Bradycardia: 4.60%; Tachycardia: 3.10% | not reported | |||

|