Abstract

Flavin-dependent halogenases (FHals) catalyse the halogenation of electron-rich substrates, mainly aromatics. Halogenated compounds have many applications, as pharmaceutical, agrochemicals or as starting materials for the synthesis of complex molecules. By exploring the sequenced bacterial diversity, we discovered and characterized XszenFHal, a novel FHal from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii, a symbiotic bacterium of entomopathogenic nematode. The substrate scope of XszenFHal was examined and revealed activities towards tryptophan, indole and indole derivatives, leading to the formation of the corresponding 5-chloro products. XszenFHal makes a valuable addition to the panel of flavin-dependent halogenases already discovered and enriches the potential for biotechnology applications by allowing access to 5-halogenated indole derivatives.

Keywords: Flavin-dependent halogenases, Biocatalysis, Electrophilic halogenation, Regioselectivity, Indole derivatives

Introduction

Halogenated compounds are a major category of molecules in organic chemistry as finished products with applications in pharmacy and agrochemistry, but also as intermediates in metal-catalyzed coupling reactions. Halogenations of aromatic cycles are still an issue in conventional synthesis, due to low reactivity and medium selectivity, which makes this route a real challenge on industrial scale. As a possible answer, the use of enzyme catalysed halogenation reaction is particularly interesting in a greener context (Fraley and Sherman 2018; Gkotsi et al. 2018; Latham et al. 2018; Schnepel and Sewald 2017; Weichold et al. 2016). Flavin-dependent halogenases (FHals) are halogenating enzymes catalyzing electrophilic halogenation of electron-rich aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds. They use harmless alkali halides and are highly regioselective; therefore they represent a promising alternative to conventional halogenation methods (Maddox et al. 2015; Mitchell et al. 1979; Prakash et al. 2004; Samanta and Yamamoto 2015; Schröder et al. 2012; van Pee 2012).

Flavin-dependent halogenases constitute a small enzyme family belonging to the superfamily of flavin-dependent monooxygenases and only few enzymes are described which restricts their application in synthesis (Gkotsi et al. 2018; Latham et al. 2018; Mascotti et al. 2016). The halogenase PrnA was the first FHal to be identified. It catalyses the C7-regioselective halogenation of tryptophan in the biosynthetic pathway of pyrrolnitrin, an antifungal metabolite produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. The purification and characterization of this enzyme reveal that its activity was Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) dependent and requires a NAD(P)H flavin reductase for FADH2 supply (Hohaus et al. 1997; Keller et al. 2000). Structural elucidation of PrnA by X-ray crystallography allowed to propose a mechanism for the electrophilic regioselective halogenation (Dong et al. 2005; Keller et al. 2000). FHals are active towards electron-rich substrates such as indole and phenol derivatives, but also β-keto carbonyl moieties (Jungmann et al. 2015; Podzelinska et al. 2010; van Pee and Patallo 2006).

Many of these enzymes are incorporated in the enzymatic machinery of polyketide or non-ribosomal peptide synthases and are, therefore, not readily available for biocatalytic purposes (Buedenbender et al. 2009; Chiu et al. 2001; Dorrestein et al. 2005; Heide et al. 2008; Hornung et al. 2007; Jungmann et al. 2015; Lin et al. 2007; Podzelinska et al. 2010; Rachid et al. 2006; Son et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2002). To access new FHals and thus broaden the range of possibilities, one option is to explore the extraordinary amount of available genomic resources (Zaparucha et al. 2018). As halogenated secondary metabolites are widespread compounds, halogenases can be found in various organisms and there are still a lot to discover (Neubauer et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2013; Son et al. 2017). In this study, we explored the sequenced bacterial diversity in search of novel flavin-dependent halogenases in order to find enzymes active towards aromatic electron-rich substrates.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without additional purification. d,l-tryptophan, d-tryptophan, l-tryptophan, d,l-tyrosine, 2-amino benzoic acid, 4-amino benzoic acid, 2-amino-5-chloro benzoic acid, 2-amino-3-chloro benzoic acid, 5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan, tryptamine, 3-indoleacetonitrile, 3-(2-hydroxyethyl)indole, indole, 6-chloro indole, indole-3-pyruvic acid, indole-3-acrylic acid, indole-3-butyric acid, glucose, NADH and FAD were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (MilliporeSigma, StLouis, USA). Indole-3-acetic acid was purchased from Acros Organics (Fisher Scientific SAS, Illkirch, France). Indole-3-propionic acid was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Thermo Fisher (Kandel) GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). 5-Chloro-tryptophan and 5-chloro tryptamine were purchased from Chem Impex International Inc. (Wood Dale, USA). 5-Chloro-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)indole and 5-chloro-indole-3-acetamide were purchased from Oxchem Corporation (Wood Dale, USA). 5-Bromo-tryptophan, 5-chloro-indole-3-acetonitrile and 5-chloroindole were purchased from Enamine (LLC Monmouth Jct, USA). Indole-3-acetamide was purchased from TCI Europe (Zwijndrecht, Belgium). 7-Chloro tryptophan was a generous gift from Dr. Eugenio P. Patallo (Institut für Biochemie, TU Dresden, 01062 Dresden, Germany) (Zhu et al. 2009). Regeneration enzyme glucose dehydrogenase 105 (GDH-105) was given by Codexis (Redwood City, USA). For the screening, filter plates were used (Acroprep Advance 96 Filter Plate, 0.2 μm GHP, Pall). For reactions in Eppendorf tubes, simple filters were used (0.2 μm, PTFE, Merck Millipore). Oligonucleotides were from Sigma-Aldrich (MilliporeSigma, StLouis, USA). E. coli strains BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL were from Agilent technologies (Santa Clara, USA). Enzymatic spectrophotometric screenings in microplates were performed on a SpectraMax Plus384 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA). Cell-free extracts in 96-microwell plates were heated using a tested thermocycler GeneAmpTM PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, USA). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker (Bruker, Billerica, USA) 600 MHz spectrometer (Evry University, France) for 1H and 13C experiments. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm and referenced with residual solvent signals. Coupling constant values (J) are given in hertz. UHPLC-UV analyses were performed on a UHPLC U3000 RS 1034 bar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with a thermostated Column Compartment Rapid Separation (TCC-3000RS) and a diode array detector DAD3000. UHPLC-HRMS analyses were performed on a UHPLC U3000 RS 1034 bar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with a Thermostated Column Compartment Rapid Separation (TCC-3000RS) coupled to ultra-high resolution Orbitrap Elite hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI) source.

Selection of candidate enzymes

A three-step process was conducted for searching new FHals (Vergne-Vaxelaire et al. 2013). First of all, a reference set was created by collecting known proteins from the literature (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Figure S1). Second, this set was used for protein-versus protein alignments, using the BL2 option (BLAST allowing gaps) and a BLOSUM62 score matrix against UniprotKB and the metagenome from Genoscope using low stringency parameters (> 30% of identity, on 80% of the length) resulting in the selection of 6574 candidate enzymes. Third, to minimize number of candidates, protein sequences were clusterized (80% of similarities) to create putative isofunctional groups using traditional all-against-all normalized BLASTP scores calculated by the LASSAP suite and a single-linkage algorithm. A representative candidate was then chosen, one by cluster, if its corresponding bacterial strain was available in the Genoscope genomic collection. All the sequences too divergent to be included in the clustering were chosen if the corresponding genome was available in the Genoscope genomic collection. Missing strains were purchased from DSMZ when available. Representatives of each cluster were cloned and engaged in screening processes.

Cloning, expression and purification

Primers were chosen and genes were cloned with a histidine tag in N-terminal part in a pET22b(+) (Novagen) modified for ligation independent cloning as already described (Bastard et al. 2014). All primers and strains of the selected FHals are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 and named from FHal1 to FHal148. All the strains along with their identifiers were purchased from DSMZ, CIP or ATCC collections. When DNA samples corresponding to the gene encoding the selected enzyme was not available, PCR was performed on the DNA of another strain from the same species as noted in Additional file 1: Table S2. All sequences were verified. Each expression plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL. Cell culture, induction of protein production and cell lysis were conducted as previously published (Bastard et al. 2014). Selected enzymes from the screening (FHal13, FHal16, FHal35, FHal46, FHal57, FHal106) were then purified by loading the clear crude cell extract from 100 mL of culture onto a Ni–NTA column (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The elution buffer was 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole and 10% glycerol. The flavin reductase from E. coli strain K12 (K12Fre) (UniProtKB ID: P0AEN1) was chosen as universal reductase for all FHAls. K12Fre was cloned, overexpressed and purified following the same protocol. Large scale protein purification was conducted from a 2 × 500 mL culture and was performed using a preparative chromatography system (Äkta Pure; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). A fully automated two-step method was set up in which a His Trap FF 5-mL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) column was used in the first purification step. The eluted peak was redirected on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200-pg size exclusion column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and collected in 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol. Purified enzymes were stored at − 80 °C. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using the NuPAGE system. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method, with bovine serum albumin as the standard (Bio-Rad).

Enzymatic screening assay on aromatic electron-rich substrates

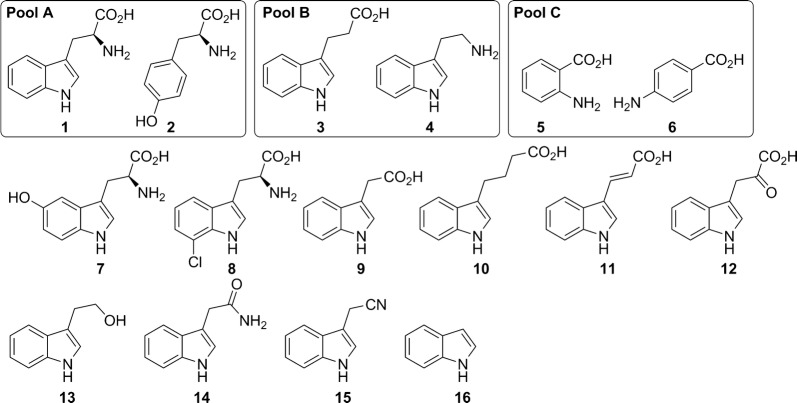

The candidate FHals were screened as cell-free extracts in 96-microwell plates. Cell-free extracts were stored at − 80 °C, and thawed out on ice before use. The enzymatic reactions were carried out on three pools, A–B–C, composed of two substrates (vide infra) (final concentration 0.5 mM each), NaCl (20 mM), NADH (0.5 mM), FAD (1 μM), cell-free extract (10 μL), isopropanol (5 μL), phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH = 7.4) in a final volume of 100 μL at RT for 24 h. TFA (1 μL) was then added in each well, followed by 100 μL of water (Fig. 1). The microplates were centrifuged at 6000g for 10 min and the supernatants were filtrated in new microplates using filter plates (Acroprep Advance 96 Filter Plate, 0.2 µm GHP, Pall). A volume of 2 μL was then injected on UHPLC according to the conditions described below. Hits were determined by comparison with the reaction with cell-free extract without overexpressed protein. UHPLC analyses were conducted on an Accucore PFP (Thermo Scientific) column (50 * 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm) with eluents A (H2O + 0.1% formic acid) and B (CH3CN). Halogenated products were identified by UHPLC by comparison on their retention time with the ones of halogenated standards when available, and by mass spectroscopy. Pool A, tryptophan (1) and tyrosine (2): linear gradient (ratio A/B 99/1 during 1 min, then 99/1 to 85/15 in 2.5 min, then 85/15 during 2 min, then 85/15 to 50/50 in 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 276 nm. Pool B, tryptamine (3) and indol-3-acetic acid (4): linear gradient (ratio A/B 80/20 to 40/60 in 3 min, then 40/60 during 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 290 nm. Pool C, 2-aminobenzoic acid (5) and 4-aminobenzoic acid (6): linear gradient (ratio A/B 95/5 during 0.5 min, then 95/5 to 70/30 during 1 min, then 70/30 to 50/50 during 1.5 min, then 50/50 during 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 290 nm and λ = 330 nm.

Fig. 1.

Substrate structures

Characterization of XszenFHal (FHal16) from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii DSM 16338

All specific activities and kinetic parameters were determined from duplicate experiments. All reactions were performed on purified XszenFHal (Uniprot ID: W1J423) at 25 °C in 100 μL scale and monitored by UHPLC-UV (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

-

i.

Standard conditions. The assay mixture comprised 1 mM substrate, 1 mg/mL XszenFHal, 0.22 mg/mL K12Fre, 20 mM NaCl, 3 mM glucose, 3 U/mL GDH-105, 0.05 mM NADH, 1 μM FAD in phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.4. The reaction was stirred at 500 rpm for 24 h then 1 μM TFA and 70 μL isopropanol were added. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered over PVDF membrane filter 0.2 μm and analyzed by UHPLC-UV (see below, UHPLC conditions for microscale reactions).

-

ii.

Halide tolerance. The assay mixture comprised 1 mM l-tryptophan, 0.25 mg/mL XszenFHal, 0.055 mg/mL K12Fre, 20 mM NaX, 3 mM glucose, 1 U/mL GDH, 0.025 mM NADH, 1 μM FAD in phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.4. The reaction was stirred at 500 rpm for 24 h then 1 μM TFA and 70 μL isopropanol were added. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered over PVDF membrane filter 0.2 μM and analyzed by UHPLC-UV using conditions A.

-

iii.

Specific activity towards l-tryptophan (1). The assay mixture comprised 1 mM substrate, 0.2 mg/mL XszenFHal, 0.022 mg/mL K12Fre, 20 mM NaX, 3 mM glucose, 1 U/mL GDH, 0.025 mM NADH, 1 μM FAD in phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.4. The reaction was stirred at 500 rpm then 1 μM TFA and 70 μL isopropanol were added. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered over PVDF membrane filter 0.2 μm and analyzed by UHPLC-UV using conditions A.

-

iv.

Specific activities toward various substrates (Fig. 1). The typical assay mixture comprised 1 mM substrate, 0.0.25 mg/mL K12Fre, 20 mM NaCl, 3 mM glucose, 3 U/mL GDH, 0.05 mM NADH, 1 μM FAD in phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.4 and XszenFHal at the indicated concentration. Tested substrates were: 7-Cl-tryptophan (8); indole-3-ethanol (13); indole-3-acetamide (14); indole-3-acetonitrile (15). The reaction was stirred at 500 rpm then 1 μM TFA and 70 μL isopropanol were added. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered over PVDF membrane filter 0.2 μm and analyzed by UHPLC-UV. Enzyme concentration and monitoring time have been optimized to fall within the linear range of enzyme activity. The specific activities were calculated based on the quantity of product formed over the defined time period, determined by calibration curves with commercial standards.

-

v.

Determination of kinetic parameters. The assay mixture comprised 1 μM XszenFHal, 0.1 μM K12Fre, 20 mM NaCl, 0.05 mM NADH, 0.01 mM FAD in phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.5. The following tryptophan concentrations were used: 5 μM; 20 μM; 100 μM; 250 μM; 500 μM; 1000 μM; 1500 μM. The reaction was stirred at 500 rpm then 1 μM TFA and 70 μL isopropanol were added. After centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered over PVDF membrane filter 0.2 μm and analyzed by UHPLC-UV. Enzyme concentration and monitoring time have been optimized to fall within the linear range of enzyme activity. Kinetic parameters were determined by fitting initial rate data to the Michaelis–Menten equation (Additional file 1: Figure S6).

UHPLC conditions for microscale reactions

UHPLC-UV conditions for substrates (1)-(3–4)-(7–16): UPLC analyses were conducted on an Accucore PFP (Thermo Scientific) column (50 * 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm), eluents A (H2O + 0.1% formic acid) and B (CH3CN) with the following conditions:

Conditions A for substrate (1): linear gradient (ratio A/B 99/1 during 1 min, then 99/1 to 85/15 in 2.5 min, 85/15 for 2.5 min then 85/15 to 50/50 in 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 276 nm.

Conditions B for substrate (4): linear gradient (ratio A/B 80/20 to 40/60 in 3 min, 40/60 for 2.5 min then 40/60 to 20/80 in 1.5 min, 20/80 for 0.5 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 220, 245, 280 and 330 nm.

Conditions C for substrate (7): linear gradient (ratio A/B 95/5 for 0.5 min, 95/5 to 70/30 in 1 min, 70/30 to 30/70 in 2 min, 30/70 for 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 230, 275, 280 and 330 nm.

Conditions D for substrates (8–9)-(13–14)-(16): linear gradient (ratio A/B 80/20 to 10/90 in 3.5 min, then 10/90 for 1 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 220 and 280 nm.

Conditions E for substrates (3)-(10–12)-(15): linear gradient (ratio A/B 60/40 to 10/90 in 2.5 min, then 10/90 for 2 min), flow 0.4 mL/min, λ = 220, 230, 280 and 330 nm.

Synthesis of 5,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan (17)

The synthesis of 5,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan (17) was accomplished following a procedure described by Heemstra and coworkers for the synthesis of 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan (Heemstra and Walsh 2008) (Additional file 1: Scheme S1).

5,7-Dichloro l-tryptophan. RMN 1H (CD3OD, 600 mHz): δ 7.68 (s, 1H, H-4); 7.39 (s, 1H, H-2); 7.26 (s, 1H, H-6); 3.45 (m, 1H, H-11); 3.24 to 3.07 (m, 2H, H-10). RMN 13C (CD3OD, 125 mHz): δ 176.0 (C-12); 132.7 (C8); 130.8 (C-9); 128.3 (C-2); 123.9 (C-7); 120.8 (C-6); 118.3 (C-4); 117.3 (C-5); 112.0 (C-3); 55.5 (C-11); 27.6 (C-10). HRMS (ESI+): [M+H]+ m/z calcd for C11H10Cl2N2O2, 273.01921; found 273.01940.

Results

Halogenase screening

The protein sequences of 22 known FHals were used in a sequence-driven approach to build a collection of halogenase similar enzymes (Vergne-Vaxelaire et al. 2013). 6574 proteins sharing at least 30% identity over at least 80% of the length with the enzymes from reference set were collected. Proteins have been clustered based on sequence identity (≥ 80%) and one representative per cluster, for which genomic DNA was available in the Genoscope strain collection, was chosen. From the 417 candidates selected to represent sequence diversity, 148 genes were successfully cloned in an expression vector (Additional file 1: Table S2). After overexpression of recombinant genes in Escherichia coli strain BL21, cells were lyzed and the proteins were quantified. No extra flavin reductase (Fre) was added as E. coli contains naturally occurring flavin reductases. The candidate enzymes were screened as cell-free extracts against six aromatic electron-rich substrates grouped in three pools of two compounds (Fig. 1). Halogenase activity was assayed by UHPLC-UV. Only four enzymes were found to be very weakly or moderately active compared to a blank reaction, FHal13 (UniProtKB ID: Q4J6K2), FHal35 (UniProtKB ID: B7J6K4) and FHal46 (UniProtKB ID: C7PAY7) towards substrates from pool C, and FHal16 (UniProtKB ID: W1J423) towards substrates from pools A and C. The four enzymes cloned with a polyhistidine tag were purified by nickel affinity chromatography for further studies and their activities were verified on single substrate. In our reaction conditions, only FHal16 confirmed to have a halogenase activity and was found to be active towards tryptophan. FHal16, from X. szentirmaii DSM16338, has been named XszenFHal.

Characterization of XszenFHal

XszenFHal, from X. szentirmaii DSM16338, shares ~ 60% sequence identity with PyrH (Uniprot ID: A4D0H5), its closest homolog in the reference set (Gualtieri et al. 2014). PyrH is involved in the pyrroindomycin B biosynthesis, an antibiotic compound produced by Streptomyces rugosporus LL-42D005, where it catalyzes the C5 chlorination of tryptophan (Zehner et al. 2005) (Additional file 1: Figures S3 and S4). X. szentirmaii is a symbiotic bacterium of entomopathogenic nematode (Lengyel et al. 2005). It is known to produce various secondary metabolites, xenofuranones A and B, two phenylpyruvate dimers, szentiamide, a depsipeptide and fabclavines, PK-NRP-polyamine hybrids (Brachmann et al. 2006; Ohlendorf et al. 2011; Wenski et al. 2019) (Additional file 1: Figure S4). From all these metabolites, only szentiamide has a tryptophan moiety but it is non chlorinated. The analysis of the genomic context of gene encoding XszenFHal did not reveal any clear metabolic role. Its native substrate is so difficult to hypothesize.

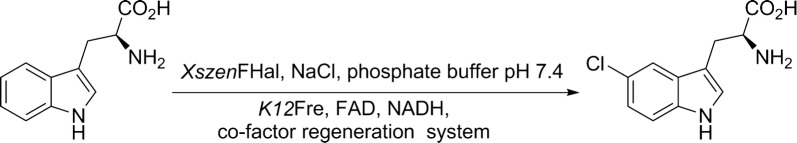

Purified XszenFHal was obtained on large scale using fully automated two-step method combining nickel affinity and size exclusion chromatography. To evaluate the substrate range of XszenFHal, we screened it against various substrates. Because the preliminary screening showed that XszenFHal was only active towards tryptophan and had no activity towards tyrosine and aniline derivatives, we focused our study on indole derivatives (Fig. 1). Purified XszenFHal and K12Fre were used to optimize the reaction conditions of tryptophan chlorination on small scale including glucose dehydrogenase as cofactor regeneration system (Payne et al. 2013; van der Donk and Zhao 2003; Yeh et al. 2005) (Scheme 1). Standard conditions were then used since no variation in parameters (NADH, FAD, NaCl) has allowed any improvement.

-

i.

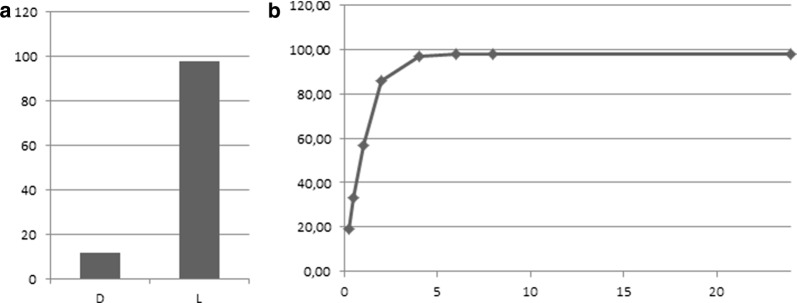

Stereospecificity

XszenFHal showed a clear stereopreference for the l-enantiomer with a 98% conversion into the chloro derivative within 6 h, while the conversion only reached 12% for the d-enantiomer over 24 h (Fig. 2).

-

ii.

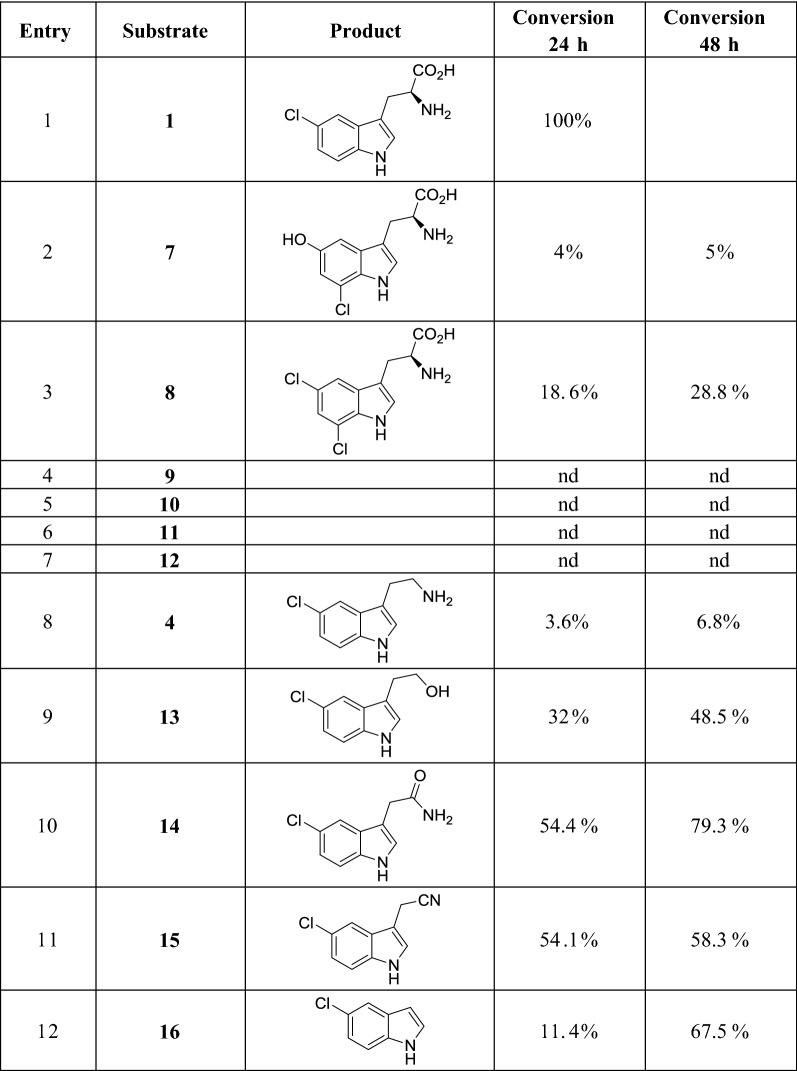

Substrate activity profile

XszenFHal was screened against various indole derivatives (7–16) (Fig. 1). The enzyme exhibited broad scope, seven of the 11 substrates being halogenated with low (entries 2 and 8) to medium (entries 10 and 11) conversions over 24 h and up to good (entries 10 and 12) conversions over 48 h (Table 1). None of the indole derivatives substituted with carboxylic acid functions was found to be substrate (entries 4–7). It is worthy to note that XszenFHal was active towards all the simple indole derivatives with moderate to good conversions (entries 9–11) except in the case of the tryptamine for which a low conversion was obtained (entry 8).

-

iii.

Regioselectivity

Chlorination by XszenFHal is C5 regioselective as demonstrated by comparison on UHPLC-UV analysis of the products with the UHPLC chromatograms of halogenated standards (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

-

iv.

Halide tolerance

We tested XszenFHal for its ability to catalyze bromination and iodination of l-tryptophan, in addition to chlorination. Under standard conditions, XszenFHal fully converted l-tryptophan to the 5-chloro derivative while bromination under the same conditions led to a 64% conversion (Additional file 1: Figure S5). No conversion was observed with NaI.

Scheme 1.

Chlorination of l-tryptophan catalyzed by XszenFHal

Fig. 2.

a d- and l-tryptophan conversions by XszenFHal with NaCl over 24 h. b Time course of l-tryptophan conversion by XszenFHal with NaCl over 24 h

Table 1.

Conversion of various substrates by XszenFHal with NaCl

Kinetic constants

-

i.

Specific activities

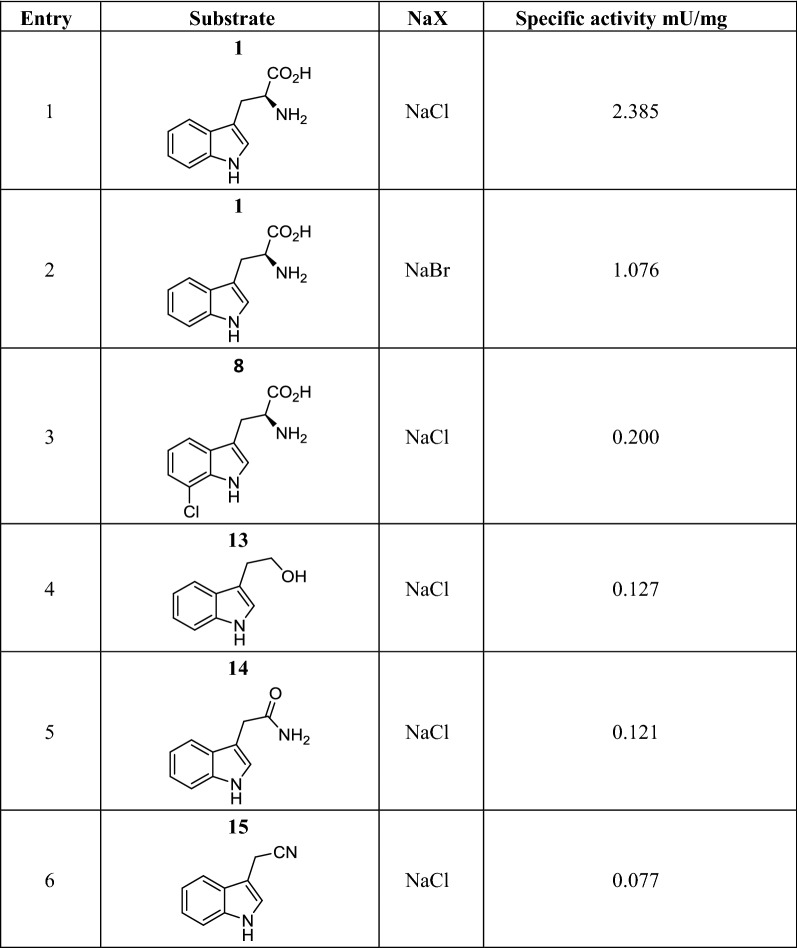

Specific activities were determined with l-tryptophan under NaCl and NaBr conditions and under NaCl conditions for the other substrates (Table 2). Specific activities were found moderate with l-tryptophan (entries 1–2) with ca. 2 times lower activity with NaBr (1.076 mU/mg) compared to NaCl (2.385 mU/mg). For indole derivatives, the specific activities were significantly lower, with values at least 10 times lower (entries 3–6).

-

ii.

Kinetic constants with l-tryptophan

Under NaCl conditions, the kinetic parameters were measured with respective values of Vm 4.44 μM min−1 (88.8 U/mg enzyme); Km 58.22 μM; kcat 4.44 min−1 which results in a catalytic efficiency of kcat/Km 0.076 min−1.M−1 (Additional file 1: Figure S6).

Table 2.

Specific activities of XszenFHal on various substrates

One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the conversion of 1 µM of substrate per minute

Discussion

In this work, we present the discovery and characterization of XszenFHal, a novel 5-regioselective tryptophan halogenase belonging to the flavin-dependent halogenase family. Only one tryptophan 5-halogenase active towards isolated amino acid has been characterized so far, PyrH (UniProtKB ID A4D0H5) from Streptomyces rugosporus, but without study of its substrate range (Zehner et al. 2005). Recently, two other 5-regioselective tryptophan halogenases have been identified in biosynthetic pathways but they are implied in tailoring modifications of metabolites and are active towards tethered peptides. MibH (UniProtKB ID: W2EQU4) is responsible of the 5-chlorination of tryptophan in lantibiotic NAI-107, a ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP) produced by the actinomycete Microbispora sp. 107891, and Ulm24 (UniProtKB ID: A0A2D3E318) was identified in the genome of Streptomyces sp. KCB13F003 which produced ulleungmycins A and B, two chlorinated non-ribosomal peptides (NRP) (Ortega et al. 2017; Son et al. 2017). XszenFHal shares nearly 60% identity with PyrH and Ulm24, and only 30% identity with MibH (Additional file 1: Figure S7).

Similar to tryptophan 5-, 6- and 7-halogenases, XszenFHal exhibits residual activity towards substrates in addition to tryptophan (Andorfer et al. 2017; Frese et al. 2014; Menon et al. 2016; Neubauer et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2017). Nevertheless, as the examination of the metabolic context of the gene encoding for XszenFHal did not provide any indication, there is no formal evidence that tryptophan is the metabolic substrate of XszenFHal. However, XszenFHal kinetic data are consistent to the ones of halogenases for which tryptophan is the metabolic substrate (Additional file 1: Table S3) (Dong et al. 2005; Heemstra and Walsh 2008; Luhavaya et al. 2019; Yeh et al. 2005; Zeng and Zhan 2011; Zhu et al. 2009). When compared to PyrH, the other 5-regioselective tryptophan halogenase, XszenFHal exhibits kinetic values fairly similar with kcat of 4.44 min−1 for XszenFHal and 3.56 min−1 for PyrH, and substrate binding value, Km 58.22 μM for XszenFHal and 109 for PyrH, resulting in a higher catalytic efficiency for XszenFHal, kcat/Km 0.076 min−1 M−1 for XszenFHal compared to 0.033 min−1 for PyrH (Zhu et al. 2009). The specific activity values of XszenFHal on the different substrates show significant differences, with value at least 10 times higher for tryptophan, indicating that it is the best substrate within the tested ones. Tryptophan (1) and 7-chloro tryptophan (8) were halogenated with a 5-regioselectivity, while the 5-hydroxy tryptophan (7) was halogenated with a 7-regioselectivity, which corresponds to the other activated position. In our conditions, the conversion was total for tryptophan in 24 h, and much lower for substrates (7) and (8) (Table 1). Very interestingly, XszenFHal exhibited activity towards indole (16) and 3-substituted derivatives (4; 13-15) (Tables 1, 2). These results are promising for synthetic applications. Indeed, under conventional chemistry conditions, no 5-regioselective chlorination of simple indole derivatives is possible except in the case of tryptamine (4) (Somei et al. 1995; Hasegawa et al. 1999); for substrates (13–15) the 5-regioselective chlorination can occur only when the indole moiety is part of a more complex molecule (Bell and Stump Craig; Chatterjee et al.; Clerin et al.; Laronze et al. 2005); regarding simple indole (16), the direct chlorination by conventional synthetic methods undergoes to the formation of 5,7-dichloro indole (2000; Vennemann et al.). In addition, halogenated-5 indole and derivatives could be easily modified by metal-catalyzed coupling reactions to produce various compounds (Batail et al. 2011). It is worthy to note that combination of biocatalysis and palladium catalysis gave access to new C–H activation transformations than cannot be achieved by single catalysis (Durak et al. 2016; Latham et al. 2016; Roy et al. 2010).

Our studies led to the identification of XszenFHal, a novel tryptophan 5-halogenase from X. szentirmaii. Study of XszenFHal substrate scope revealed that, in addition to tryptophan, XszenFHal is also active towards substituted tryptophan, indole and indole derivatives. It thus completes the range of regioselectivities achievable in biocatalysis by allowing the synthesis of 5-halogenated tryptophan, indole and indole derivatives. These results show the potential of XszenFHal for synthetic applications.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Scheme S1. Synthesis of 5,7-dichloro-L-tryptophan (17). Table S1. Enzymes used for the reference set. Table S2. Primers used for cloning of the 148 candidate FHals and the corresponding strains used for PCR gene amplification. Table S3. Kinetic parameters of FHals for which tryptophan is the metabolic substrate; comparison with the kinetic parameters of XszenFHal. Figure S1. Matrice of the reference set. Figure S2. UHPLC traces of substrates and their corresponding chlorinated derivatives. Figure S3. MS spectra of 5-chlorotryptophan. Figure S4. Secondary metabolites from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii. Figure S5. A. UHPLC trace of the tryptophan bromination reaction by XszenFHal. B. Time course of the conversion of tryptophan by XszenFHal with NaBr over time. Figure S6. Plots for determination of kinetic parameters of XszenFHal. A. Determination of the initial velocity. B. Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Figure S7. Percent identity matrix of the sequences of the 5-tryptophan halogenases.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eugenio P. Patallo (Institut für Biochemie, TU Dresden, 01062 Dresden, Germany) for sending a sample of 7-chloro tryptophan. They would like to thank Olek Maciejak and Marie-Jeanne Clément (SABNP, INSERM U 1204—Université d’Evry Val-d’Essonne, Université Paris-Saclay, France) for assistance in 1H and 13C NMR experiments, the Region Ile de France for financial support of the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer, Dr. Alain Perret, Christine Pelle and Peggy Sirvain for protein supply, Virginie Pellouin for technical support.

Authors’ contributions

AZ conceived the project and directed it with CVV, VdB and J-LP performed the candidate enzyme selection. AD carried out the gene cloning, the protein expression and purification on a small scale with input from J-LP, JD, DE and AFJ conducted the experiments. AZ wrote the manuscript with input from CVV and VdB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jérémy Domergue and Diane Erdmann contributed equally to this work

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13568-019-0898-y.

References

- Andorfer MC, Grob JE, Hajdin CE, Chael JR, Siuti P, Lilly J, Tan KL, Lewis JC. Understanding flavin-dependent halogenase reactivity via substrate activity profiling. ACS Catal. 2017;7(3):1897–1904. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b02707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard K, Thil Smith AA, Vergne-Vaxelaire C, Perret A, Zaparucha A, De Melo-Minardi R, Mariage A, Boutard M, Debard A, Lechaplais C, Pelle C, Pellouin V, Perchat N, Petit JL, Kreimeyer A, Medigque C, Weissenbach J, Artiguenave F, de Berardinis V, Vallenet D, Salanoubat M. Revealing the hidden finctional diversity of an enzyme family. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(1):42–49. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batail N, Genelot M, Dufaud V, Joucla L, Djakovitch L. Palladium-based innovative catalytic procedures: designing new homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts for the synthesis and functionalisation of N-containing heteroaromatic compounds. Catal Today. 2011;173(1):2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2011.03.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell IAN, Stump CA. Tricyclic anilide heterocyclic cgrp receptor antagonists. WO2008153852 A1 2008-12-18 [WO2008153852]

- Brachmann AO, Forst S, Furgani GM, Fodor A, Bode HB. Xenofuranones A and B: phenylpyruvate dimers from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii. J Nat Prod. 2006;69(12):1830–1832. doi: 10.1021/np060409n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buedenbender S, Rachid S, Müller R, Schulz GE. Structure and action of the myxobacterial chondrochloren halogenase CndH: a new variant of FAD-dependent halogenases. J Mol Biol. 2009;385(2):520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Diebold James L, Dunn D, Hudkins Robert L, Dandu R, Wells Gregory J, Zulli Allison L. Cycloalkanopyrolocarbazole derivatives and the use thereof as parp, vegfr2 and mlk3 inhibitors. WO200185686 A2 2001-11-15 [WO200185686]

- Chiu HT, Hubbard BK, Shah AN, Eide J, Fredenburg RA, Walsh CT, Khosla C. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the complestatin biosynthetic gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(15):8548–8553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151246498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerin V, Lee K, Smith Thomas M. Use of inhibitors of cytosolic phospholipase a2 in the treatment of thrombosis. WO2007140317 A2 2007-12-06 [WO2007140317]

- Dong C, Flecks S, Unversucht S, Haupt C, van Pée K-H, Naismith JH. Tryptophan 7-halogenase (PrnA) structure suggests a mechanism for regioselective chlorination. Science. 2005;309(5744):2216–2219. doi: 10.1126/science.1116510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrestein PC, Yeh E, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Dichlorination of a pyrrolyl-S-carrier protein by FADH2-dependent halogenase PltA during pyoluteorin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(39):13843–13848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506964102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durak LJ, Payne JT, Lewis JC. Late-stage diversification of biologically active molecules via chemoenzymatic C–H functionalization. ACS Catal. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b02558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley AE, Sherman DH. Halogenase engineering and its utility in medicinal chemistry. Bioor Med Chem Lett. 2018;28(11):1992–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese M, Guzowska PH, Voß H, Sewald N. Regioselective enzymatic halogenation of substituted tryptophan derivatives using the FAD-dependent halogenase RebH. ChemCatChem. 2014;6(5):1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201301090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gkotsi DS, Dhaliwal J, McLachlan MMW, Mulholand KR, Goss RJM. Halogenases: powerful tools for biocatalysis (mechanisms applications and scope) Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2018;43:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri M, Ogier J-C, Pagès S, Givaudan A, Gaudriault S. Draft genome sequence and annotation of the entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus szentirmai strain DSM16338. Genome Announc. 2014;2(2):e00190-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00190-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Yamada K, Nagahama Y, Somei M. The chemistry of indoles Part 94 - A novel methodology for preparing 5-chloro- and 5-bromotryptamines and tryptophans, and its application to the synthesis of (+/-)-bromochelonin B. Heterocycles. 1999;51(12):2815–2821. doi: 10.3987/COM-99-8721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heemstra JR, Walsh CT. Tandem action of the O2- and FADH2-dependent halogenases KtzQ and KtzR produce 6,7-dichlorotryptophan for kutzneride assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(43):14024–14025. doi: 10.1021/ja806467a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heide L, Westrich L, Anderle C, Gust B, Kammerer B, Piel J. Use of a halogenase of hormaomycin biosynthesis for formation of new clorobiocin analogues with 5-chloropyrrole moieties. ChemBioChem. 2008;9(12):1992–1999. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohaus K, Altmann A, Burd W, Fischer I, Hammer PE, Hill DS, Ligon JM, van Pée K-H. NADH-dependent halogenases are more likely to be involved in halometaolite biosynthesis than haloperoxidases. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1997;36(18):2012–2013. doi: 10.1002/anie.199720121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung A, Bertazzo M, Dziarnowski A, Schneider K, Welzel K, Wohlert SE, Holzenkampfer M, Nicholson GJ, Bechthold A, Sussmuth RD, Vente A, Pelzer S. A genomic screening approach to the structure-guided identification of drug candidates from natural sources. ChemBioChem. 2007;8(7):757–766. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann K, Jansen R, Gerth K, Huch V, Krug D, Fenical W, Müller R. Two of a kind—the biosynthetic pathways of chlorotonil and anthracimycin. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(11):2480–2490. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Wage T, Hohaus K, Hölzer M, Eichhorn E, van Pée K-H. Purification and partial characterization of tryptophan 7-halogenase (PrnA) from Pseudomonas fluorescens. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39(13):2300–2302. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000703)39:13<2300::aid-anie2300>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laronze M, Boisbrun M, Léonce S, Pfeiffer B, Renard P, Lozach O, Meijer L, Lansiaux A, Bailly C, Sapi J, Laronze JY. Synthesis and anticancer activity of new pyrrolocarbazoles and pyrrolo-β-carbolines. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(6):2263–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham J, Henry J-M, Sharif HH, Menon BRK, Shepherd SA, Greaney MF, Micklefield J. Integrated catalysis opens new arylation pathways via regiodivergent enzymatic C–H activation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11873. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham J, Brandenburger E, Shepherd SA, Menon BRK, Micklefield J. Development of halogenase enzymes for use in synthesis. Chem Rev. 2018;118(1):232–269. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel K, Lang E, Fodor A, Szállás E, Schumann P, Stackebrandt E. Description of four novel species of Xenorhabdus, family Enterobacteriaceae: Xenorhabdus budapestensis sp. nov., Xenorhabdus ehlersii sp. nov., Xenorhabdus innexi sp. nov., and Xenorhabdus szentirmaii sp. nov. Sys Appl Microbiol. 2005;28(2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Van Lanen SG, Shen B. Regiospecific chlorination of (S)-β-tyrosyl-S-carrier protein catalyzed by SgcC3 in the biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(41):12432–12438. doi: 10.1021/ja072311g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhavaya H, Sigrist R, Chekan JR, McKinnie SMK, Moore BS. Biosynthesis of l-4-chlorokynurenine, an antidepressant prodrug and a non-proteinogenic amino acid found in lipopeptide antibiotics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(25):8394–8399. doi: 10.1002/anie.201901571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox SM, Nalbandian CJ, Smith DE, Gustafson JL. A practical lewis base catalyzed electrophilic chlorination of arenes and heterocycles. Org Lett. 2015;17(4):1042–1045. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascotti ML, Juri Ayub M, Furnham N, Thornton JM, Laskowski RA. Chopping and changing: the evolution of the flavin-dependent monooxygenases. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(15):3131–3146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon BRK, Latham J, Dunstan MS, Brandenburger E, Klemstein U, Leys D, Karthikeyan C, Greaney MF, Shepherd SA, Micklefield J. Structure and biocatalytic scope of thermophilic flavin-dependent halogenase and flavin reductase enzymes. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14(39):9354–9361. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RH, Lai Y-H, Williams RV. N-Bromosuccinimide-dimethylformamide: a mild, selective nuclear monobromination reagent for reactive aromatic compounds. J Org Chem. 1979;44(25):4733–4735. doi: 10.1021/jo00393a066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer PR, Widmann C, Wibberg D, Schröder L, Frese M, Kottke T, Kalinowski J, Niemann HH, Sewald N. A flavin-dependent halogenase from metagenomic analysis prefers bromination over chlorination. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0196797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlendorf B, Simon S, Wiese J, Imhoff JF. Szentiamide, an N-formylated cyclic depsipeptide from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii DSM 16338T. Nat Prod Commun. 2011;6(9):1247–1250. doi: 10.1177/1934578x1100600909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega MA, Cogan DP, Mukherjee S, Garg N, Li B, Thibodeaux GN, Maffioli SI, Donadio S, Sosio M, Escano J, Smith L, Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Two flavoenzymes catalyze the post-translational generation of 5-chlorotryptophan and 2-aminovinyl-cysteine during NAI-107 biosynthesis. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12(2):548–557. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JT, Andorfer MC, Lewis JC. Regioselective arene halogenation using the FAD-dependent halogenase RebH. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(20):5271–5274. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podzelinska K, Latimer R, Bhattacharya A, Vining LC, Zechel DL, Jia Z. Chloramphenicol biosynthesis: the structure of CmlS, a flavin-dependent halogenase showing a covalent flavin–aspartate bond. J Mol Biol. 2010;397(1):316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash GKS, Mathew T, Hoole D, Esteves PM, Wang Q, Rasul G, Olah GA. N-Halosuccinimide/BF3–H2O, efficient electrophilic halogenating systems for aromatics. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(48):15770–15776. doi: 10.1021/ja0465247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid S, Krug D, Kunze B, Kochems I, Scharfe M, Zabriskie TM, Blocker H, Muller R. Molecular and biochemical studies of chondramide formation-highly cytotoxic natural products from Chondromyces crocatus Cm c5. Chem Biol. 2006;13(6):667–681. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AD, Grüschow S, Cairns N, Goss RJM. Gene expression enabling synthetic diversification of natural products: chemogenetic generation of pacidamycin analogs. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(35):12243–12245. doi: 10.1021/ja1060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta RC, Yamamoto H. Selective halogenation using an aniline catalyst. Chem Eur J. 2015;21(34):11976–11979. doi: 10.1002/chem.201502234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepel C, Sewald N. Enzymatic halogenation: a timely strategy for regioselective C–H activation. Chem Eur J. 2017;23(50):12064–12086. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder N, Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. High-yielding, versatile, and practical [Rh(III)Cp*]-catalyzed ortho bromination and iodination of arenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(20):8298–8301. doi: 10.1021/ja302631j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Gruschow S, Goss RJ. Scope and potential of halogenases in biosynthetic applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17(2):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DRM, Uria AR, Helfrich EJN, Milbredt D, van Pée K-H, Piel J, Goss RJM. An unusual flavin-dependent halogenase from the metagenome of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei WA. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12(5):1281–1287. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somei M, Fukui Y, Hasegawa M. The chemistry of indoles Part 75 Preparations of tryptamine-4,5-dinones, and their diels-alder and nucleophilic addition reactions. Heterocycles. 1995;41(10):2157–2160. doi: 10.3987/COM-95-7189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Son S, Hong Y-S, Jang M, Heo KT, Lee B, Jang J-P, Kim J-W, Ryoo I-J, Kim W-G, Ko S-K, Kim BY, Jang J-H, Ahn JS. Genomics-driven discovery of chlorinated cyclic hexapeptides ulleungmycins A and B from a Streptomyces species. J Nat Prod. 2017;80(11):3025–3031. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Donk WA, Zhao H. Recent developments in pyridine nucleotide regeneration. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pee KH. Enzymatic chlorination and bromination. Methods Enzymol. 2012;516:237–257. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394291-3.00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pee KH, Patallo EP. Flavin-dependent halogenases involved in secondary metabolism in bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70(6):631–641. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennemann M, Braunger J, Gimmnich P, Baer T. Indolopyridines as inhibitors of the kinesin spindle protein (eg5). WO2009024190 A1 2009-02-26 [WO200924190]

- Vergne-Vaxelaire C, Bordier F, Fossey A, Besnard-Gonnet M, Debard A, Mariage A, Pellouin V, Perret A, Petit J-L, Stam M, Salanoubat M, Weissenbach J, De Berardinis V, Zaparucha A. Nitrilase activity screening on structurally diverse substrates: providing biocatalytic tools for organic synthesis. Adv Synth Catal. 2013;355(9):1763–1779. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201201098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weichold V, Milbredt D, van Pée K-H. Specific enzymatic halogenation—from the discovery of halogenated enzymes to their applications in vitro and in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55(22):6374–6389. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenski SL, Kolbert D, Grammbitter GLC, Bode HB. Fabclavine biosynthesis in X. szentirmaii: shortened derivatives and characterization of the thioester reductase FclG and the condensation domain-like protein FclL. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;46(3):565–572. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-02124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E, Garneau S, Walsh CT. Robust in vitro activity of RebF and RebH, a two-component reductase/halogenase, generating 7-chlorotryptophan during rebeccamycin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(11):3960–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500755102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu TW, Bai L, Clade D, Hoffmann D, Toelzer S, Trinh KQ, Xu J, Moss SJ, Leistner E, Floss HG. The biosynthetic gene cluster of the maytansinoid antitumor agent ansamitocin from Actinosynnema pretiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(12):7968–7973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092697199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaparucha A, de Berardinis V, Vaxelaire-Vergne C. Chapter 1. Genome mining for enzyme discovery. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2018. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zehner S, Kotzsch A, Bister B, Sussmuth RD, Mendez C, Salas JA, van Pee KH. A regioselective tryptophan 5-halogenase is involved in pyrroindomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces rugosporus LL-42D005. Chem Biol. 2005;12(4):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Zhan J. Characterization of a tryptophan 6-halogenase from Streptomyces toxytricini. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33(8):1607–1613. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, De Laurentis W, Leang K, Herrmann J, Ihlefeld K, van Pée K-H, Naismith JH. Structural insights into regioselectivity in the enzymatic chlorination of tryptophan. J Mol Biol. 2009;391(1):74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Scheme S1. Synthesis of 5,7-dichloro-L-tryptophan (17). Table S1. Enzymes used for the reference set. Table S2. Primers used for cloning of the 148 candidate FHals and the corresponding strains used for PCR gene amplification. Table S3. Kinetic parameters of FHals for which tryptophan is the metabolic substrate; comparison with the kinetic parameters of XszenFHal. Figure S1. Matrice of the reference set. Figure S2. UHPLC traces of substrates and their corresponding chlorinated derivatives. Figure S3. MS spectra of 5-chlorotryptophan. Figure S4. Secondary metabolites from Xenorhabdus szentirmaii. Figure S5. A. UHPLC trace of the tryptophan bromination reaction by XszenFHal. B. Time course of the conversion of tryptophan by XszenFHal with NaBr over time. Figure S6. Plots for determination of kinetic parameters of XszenFHal. A. Determination of the initial velocity. B. Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Figure S7. Percent identity matrix of the sequences of the 5-tryptophan halogenases.