Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate whether ICSI offers any benefit compared with IVF in different ovarian response categories in case of non-male factor infertility.

Methods

This is a retrospective multicenter analysis using individual patient data, conducted in 15 tertiary referral hospitals in Europe (1 center in Belgium and 14 in Spain). The study included the first cycle of all patients undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF or ICSI in a GnRH antagonist protocol. Only patients having either IVF or ICSI for non-male factor infertility were included. Patients were divided into 4 groups based on their ovarian response as follows: group A, poor responders (1–3 oocytes); group B, suboptimal responders (4–9 oocytes); group C, normal responders (10–15 oocytes); group D, high responders (> 15 oocytes).

Results

In total, 4891 patients were analyzed, of whom 4227 underwent ICSI and 664 IVF. There was no significant difference for the insemination method (ICSI vs. IVF) used among the different ovarian response categories: 87% vs. 13%, 87% vs. 13%, 86% vs. 14%, 84% vs. 16%, for groups A, B, C, and D, respectively, p value = 0.35. Mean fertilization rates and embryo utilization rates were comparable between IVF and ICSI in the whole cohort. Fresh and cumulative LBR did not differ significantly for IVF and ICSI in poor, suboptimal, normal, and high responders.

Conclusion

There is no advantage of ICSI over IVF as insemination method for non-male factor infertility, irrespective of the ovarian response. The number of oocytes retrieved has no value for the selection of the insemination procedure in case of non-male infertility.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-019-01563-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fertilization rates, Ovarian response, Oocytes, IVF, ICSI

Introduction

Conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) were developed as assisted reproductive technologies (ART) used in order inseminate oocytes in vitro. Although ICSI was originally developed for male factor infertility [1], there has been a substantial increase in the use of ICSI for all causes of infertility. In particular, based on the latest results generated from recent European registries by ESHRE including more than 500,000 fresh treatments, it seems that 71.3% of cycles were performed with ICSI in 2014, showing a rise of + 1.66% compared with 2013 [2]. Similarly, among fresh cycles in the USA, ICSI use increased from 36.4% in 1996 to 76.2% in 2012, with the largest relative increase including cycles without male factor infertility [3]. These findings are in line with a recent report showing that in some parts of the world, ICSI is performed in even 100% of conventional ovarian stimulation (COS) cycles [4].

The rationale for the use of ICSI is that it may be associated with a higher likelihood of fertilization and a potentially increased number of available embryos [3]. Thus, ICSI is still considered the first choice in many ART centers and has been suggested as a treatment for couples with unexplained infertility [5], poor responders [6], and women of advanced age [7]. These patients are assumed to have diminished fertility potential and ICSI is chosen in such cases, in order to “ensure” maximal fertilization. Nevertheless, despite its increasing use, a clear benefit of ICSI over IVF has yet to be established; with some studies even showing a detrimental effect [7, 8].

The number of oocytes retrieved is an important surrogate marker of success in reproductive medicine and an independent predictor of fresh and cumulative live birth rates (LBR) [9, 10]. There is currently no patient-based data on the effectiveness of ICSI compared with IVF according to the number of oocytes retrieved in patients with non-male factor infertility.

The aim of our study was to evaluate whether the ovarian response should affect the decision of the insemination method used in COS. The findings of this study could have implications for routine clinical practice.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective multicenter cohort study using individual patient data, conducted in 15 tertiary referral hospitals in Europe.

The study included all consecutive women attending the Centre for Reproductive Medicine (CRG) of the University Hospital of Brussels in Belgium and the 14 centers from the IVI group in Spain from January 2009 to December 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review boards.

Patients’ eligibility criteria

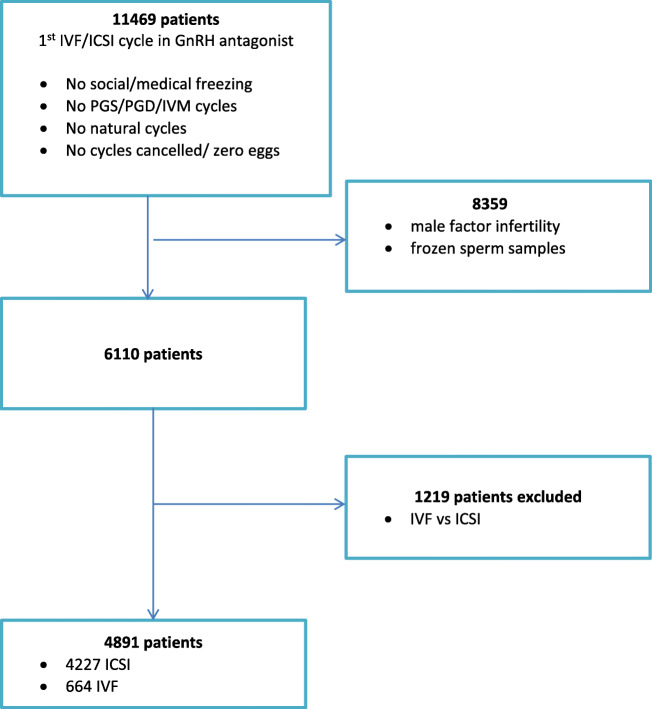

Eligible patients were considered all consecutive women between 18 and 45 years old with non-male factor infertility according to the World Health Organization (WHO) fifth edition semen analysis [11] undergoing their first ovarian stimulation cycle, in a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist protocol. Only patients having either IVF or ICSI for non-male factor infertility were included. Each patient was included only once in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the included population

Patients were excluded from the study if they had split insemination of sibling oocytes (IVF vs. ICSI) or had used frozen sperm samples. Furthermore, patients who had planned to undergo ovarian stimulation for preimplantation genetic diagnosis or screening, oocyte donation, and social or medical freezing of oocytes. In addition, we excluded women who were planned to undergo natural cycle IVF/ICSI, given that in such cases, no ovarian stimulation was used, as well as women with cycle cancelation or zero oocytes retrieved. Finally, all patients included in the study had a known fresh cycle outcome (live birth or not) and in the case that it did not deliver a live born in the fresh cycle, they were followed for at least 2 years (irrespective of the date of study entry), in order to assess the frozen-thawed cycles outcome (including exclusively those having used all the supplementary frozen embryos during this time interval).

Treatment protocol

IVF and fresh embryo transfer

Patients received daily injections of gonadotropins starting on day 2/3 of their menstrual cycle or 5 days after discontinuation of the oral contraceptive pill. From day 6 of stimulation, gonadotropin doses could be adjusted according to serum estradiol (E2) levels and ovarian response, which was assessed by vaginal ultrasound, every 2 days. The GnRH antagonist was introduced in day 6 of stimulation or when the leading follicle reached 13 mm in mean diameter. Cycle monitoring was performed through serum E2, progesterone (P) and luteinizing hormone (LH) assessments, and serial transvaginal ultrasound examinations. Ovulation triggering was performed with the administration of human or recombinant chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) as soon as three follicles of 17-mm diameter were observed. Oocyte retrieval took place 36 h later. In cases of increased risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (based on ≥ 18 follicles > 11-mm diameter on the day of final oocyte maturation triggering) triggering of ovulation was performed either by administration of GnRH agonist followed by a “freeze all” policy [12] or by GnRH agonist combined with modified luteal support [13]. In particular, in case of modified luteal support, triggering of final oocyte maturation was performed by GnRH agonist followed by a single bolus of 1.500 IU hCG IU on the day of oocyte retrieval.

Collected oocytes were inseminated either via conventional IVF or ICSI. The treating physician made the decision regarding the insemination method. Embryos were cultured up to day 3 or day 5/6 following oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer was performed under ultrasound guidance. Vaginal progesterone tablets were administered for luteal phase support from the day after oocyte retrieval until 7 weeks of pregnancy.

Cryopreservation and thawing–warming procedure

Supernumerary embryos (or all embryos in case of a “freeze all” policy) were vitrified on day 3 or day 5/6 by closed or open vitrification system. Frozen-thawed embryos were transferred following either the patients’ natural cycle or artificial preparation with or without GnRH downregulation.

Ovarian response categories

Patients were categorized into four groups according to the number of oocytes retrieved: 1–3 (group A), 4–9 (group B), 10–15 (group C), or > 15 oocytes (group D). The specific categorization was based on previous consensus papers [14] and more recent evidence suggesting that ovarian response categories should be considered as poor, suboptimal, normal, and high responders [9, 15].

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was the fertilization rate defined as the ratio of 2PN oocytes and number of oocyte–cumulus complexes in the different ovarian response categories [16, 17]. Secondary outcomes were embryo utilization rate defined as the total number of transferred and cryopreserved embryos per number of fertilized oocytes [16], fresh LBR and cumulative LBR defined as the delivery of a live born (> 24 weeks of gestation) in the fresh or in the subsequent frozen-thawed cycles in relation to the insemination method used. A live birth was defined as any birth event in which at least one baby was born alive either in the transfer of the fresh or the frozen-thawed embryos [18]. Only the first delivery was considered in the analysis.

Statistical methods

Patients’ baseline characteristics and ovarian stimulation characteristics treatment are reported according to the primary outcome (insemination method) for each ovarian response category. Continuous variables were analyzed using the independent t test or Mann–Whitney U test depending on the normality of the distribution. Normality was examined by the use of the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Furthermore, in order to assess the association between the insemination method and fertilization rate after adjustment for relevant confounders, univariate and multivariable regression models with estimation by generalized estimating equations (GEE) (using Poisson as a distribution for the main dependent variable and log as link function) were used. These models allowed also clustering for center. The potential predictors considered for the analysis were ovarian response category, female age, BMI, and cause of infertility.

Results

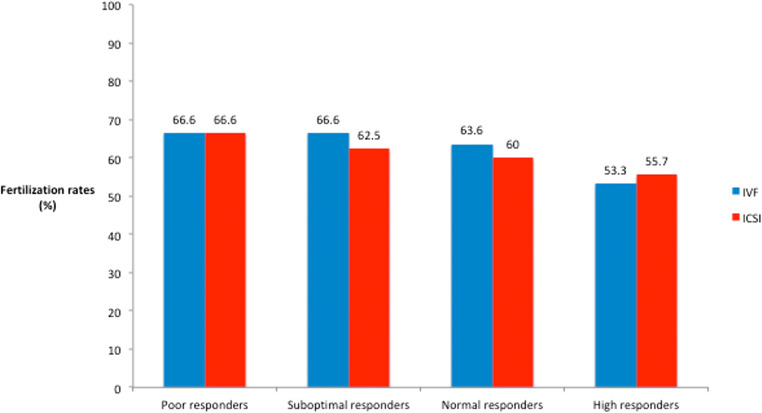

In total, 4891 patients were analyzed, of whom 4227 (86.4%) underwent ICSI and 664 (13.6%) IVF. There was no significant difference for the insemination method (IVF vs. ICSI) used among the different ovarian response categories: 13% vs. 87%, 13% vs. 87%, 14% vs. 86%, 16% vs. 84%, for groups A, B, C, and D, respectively, p value = 0.35. Fertilization rates and embryo utilization rates were comparable between IVF and ICSI in the whole cohort: (median (IQR)) (63.6% (42.9–80%) vs. 62% (47.7–77.7%) and 60% (40–100%) vs. 66.6% (40–100%), p value = 0.9 and 0.06, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fertilization rates in different ovarian response groups

Poor responders

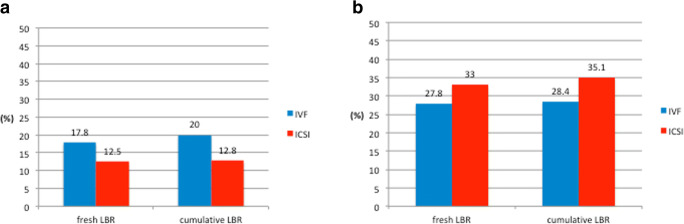

In total, 690 poor responders were included. Among them, 600 (87%) had ICSI and 90 (13%) had IVF. Age, BMI, and AFC were similar between the two groups (Table 1). However, the cause of infertility differed significantly (p = 0.03). Ovarian stimulation characteristics and embryological data are presented in Table 2. Patients who underwent ICSI had a significantly higher initial dose of stimulation compared with IVF patients (median (IQR)) (225 (200–300 vs. 225 (150–300), p value = 0.01). The duration of COS, the number of oocytes retrieved, the fertilization and embryo utilization rates, and the number and stage of embryo transfer (ET) in the fresh cycle was comparable between the two groups. For the ICSI group: metaphase II (MII) oocytes (median (IQR)) = 2 (2–3) and maturation rates (MR%) (median (IQR)) = 100% (66.6–100). Furthermore, fresh and cumulative LBR did not differ significantly for IVF and ICSI (6/90 (17.8%) vs. 75/600 (12.5%) and 18/90 (20%) vs. 77/600 (12.8%), p value = 0.16 and 0.06, respectively)) (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the poor responders (group A)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 90 (13%) | n = 600 (87%) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 38 (35–40) | 38 (34–40) | 0.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 23 (21–27) | 23 (21–26) | 0.6 |

| Infertility cause, n (%) | |||

| Endometriosis | 13 (4.4) | 65 (10.8) | 0.03 |

| PCOS | 7 (7.8) | 30 (5) | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 44 (49) | 304 (50.7) | |

| Tubal | 14 (14.4) | 47 (7.8) | |

| Unexplained | 13 (4.4) | 154 (25.7) | |

| AFC | 5 (4–7.5) | 6 (4–8) | 0.66 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Fisher’s test exact (unadjusted)

Table 2.

Ovarian stimulation characteristics in poor responders (group A)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 90 (%) | n = 600 (%) | ||

| Initial dose (IU) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 225 (150–300) | 225 (200–300) | 0.01 |

| Stimulation days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (9–12) | 10 (9–12) | 0.6 |

| Number of oocytes | |||

| Median IQR | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.15 |

| Fertilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 66.6 (33.3–100) | 66.6 (50–100) | 0.08 |

| Embryo utilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 100 (50–100) | 100 (66.6–100) | 0.6 |

| Day of embryo transfer in the fresh cycle, n (%)~ | |||

| Day 2 | 15 (20.8) | 59 (12.3) | 0.06 |

| Days 3 and 4 | 54 (75) | 375 (78) | |

| Days 5 and 6 | 4 (4.2) | 47 (9.8) | |

| Number of embryos transferred in the fresh cycle~ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.99 |

| Fresh LBR | |||

| n (%) | 16 (17.8) | 75 (12.5) | 0.16 |

| Cumulative LBR | |||

| n (%) | 18 (20) | 77 (12.8) | 0.06 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Person χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (unadjusted)

~For patients having an embryo transfer(n = 553)

Fig. 3.

Fresh and cumulative LBR according to the insemination method in poor (a) and suboptimal responders (b)

Suboptimal responders

In total, 2514 suboptimal responders were included. Among them, 2187 (87%) had ICSI and 327 (13%) had IVF. Age, BMI, and AFC were similar between the two groups (Table 3). However, the cause of infertility differed significantly (< 0.001). Patients who underwent ICSI had a significantly higher initial dose of stimulation compared with IVF patients (median (IQR)) (225 (200–300 vs. 225 (150–300), p value < 0.001) (Table 4). The duration of COS, the number of oocytes retrieved, and the fertilization and embryo utilization rates were similar between the two groups. For the ICSI group: MII oocytes (median (IQR)) = 4 (3–5) and MR% (median (IQR)) = 83% (71–100). However, more embryos were transferred in the ICSI group and the stage of ET differed significantly. Fresh and cumulative LBR did not differ significantly for IVF and ICSI (91/327 (27.8%) vs. 622/2187 (28.4%) and 108/327 (33%) vs. 768/2187 (35.1%), p value = 0.16 and 0.4, respectively)) (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of suboptimal responders (group B)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 327 (13%) | n = 2187 (87%) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 36 (33–39) | 36 (33–39) | 0.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 22.4 (20.5–25.4) | 22.5 (20.7–25) | 0.5 |

| Infertility cause, n (%) | |||

| Endometriosis | 55 (16.8) | 232 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

| PCOS | 14 (4.3) | 115 (5.3) | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 100 (30.6) | 817 (37.4) | |

| Tubal | 63 (19.3) | 225 (10.3) | |

| Unexplained | 95 (29) | 798 (36.4) | |

| AFC | 8 (5–11) | 8 (6–12) | 0.2 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Pearson’s chi-squared test (unadjusted)

Table 4.

Ovarian stimulation characteristics in suboptimal responders (group B)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 327 (13%) | n = 2187 (87%) | ||

| Initial dose (IU) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 225 (150–300) | 225 (200–300) | < 0.001 |

| Stimulation days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 0.06 |

| Number of oocytes | |||

| Median IQR | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 0.4 |

| Fertilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 66.6 (50–80) | 62.5 (50–77) | 0.4 |

| Embryo utilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 66.6 (50–100) | 66.6 (40–100) | 0.13 |

| Day of embryo transfer in the fresh cycle, n (%)~ | |||

| Day 2 | 22 (7.6) | 87 (4.5) | 0.04 |

| Days 3 and 4 | 225 (77.6) | 1499 (77.3) | |

| Days 5 and 6 | 43 (14.8) | 353(18.2) | |

| Number of embryos transferred in the fresh cycle~ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | < 0.001 |

| Fresh LBR | |||

| n (%) | 91 (27.8) | 622 (28.4) | 0.16 |

| Cumulative LBR | |||

| n (%) | 108 (33) | 768 (35.1) | 0.4 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Person χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (unadjusted)

~For patients having an embryo transfer (n = 2229)

Normal responders

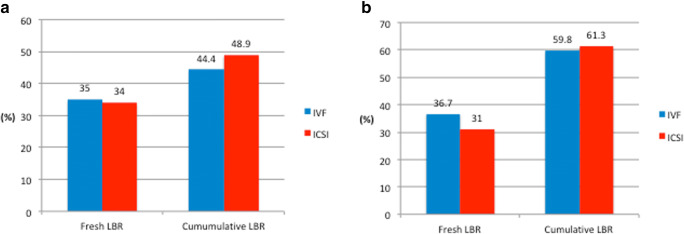

In total, 1132 normal responders were included. Among them, 972 (86%) had ICSI and 160 (14%) had IVF. BMI and AFC were similar between the two groups (Table 5). However, the age and the cause of infertility differed significantly (p = 0.04 and p < 0.001, respectively). Patients who underwent ICSI had a significantly higher starting dose of stimulation compared with IVF patients (median (IQR)) (225 (150–300) IU/day vs. 200 (150–225) IU/day, p value < 0.001) (Table 6). The duration of COS, the number of oocytes retrieved, the fertilization and embryo utilization rates, and the stage of ET in the fresh cycle was similar between the two groups. For the ICSI group: MII oocytes (median (IQR)) = 9 (8–11) and MR% (median (IQR)) = 80% (66–90). However, significantly more embryos were transferred in the ICSI group (p value < 0.001). Fresh and cumulative LBR did not differ significantly for IVF and ICSI (56/160 (35%) vs. 331/972 (34%) and 71/160 (44.4%) vs. 475/972 (48.9%), p value = 0.8 and 0.3, respectively)) (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of normal responders (group C)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 160 (14%) | n = 468 (86%) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 34.5 (31–37) | 35 (32–38) | 0.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 22 (20.6–24.4) | 22.5 (20.6–25.1) | 0.5 |

| Infertility cause, n (%) | |||

| Endometriosis | 27 (16.9) | 78 (8) | < 0.001 |

| PCOS | 16 (10) | 96 (9.9) | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 28 (17.5) | 265 (27.3) | |

| Tubal | 39 (24.4) | 111 (11.4) | |

| Unexplained | 50 (31.2) | 422 (43.4) | |

| AFC | 12 (7–15) | 12 (9–16) | 0.5 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Pearson’s chi-squared test (unadjusted)

Table 6.

Ovarian stimulation characteristics in normal responders (group C)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 160 (14%) | n = 972 (86%) | ||

| Initial dose (IU) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 200 (150–225) | 225 (150–300) | < 0.001 |

| Stimulation days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 0.8 |

| Number of oocytes | |||

| Median IQR | 11 (10–14) | 12 (11–13) | 0.3 |

| Fertilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 63.6 (48–78.6) | 60 (45.5–72.7) | 0.13 |

| Embryo utilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 50 (33.3–72.7) | 50 (33.3–66.6) | 0.4 |

| Day of embryo transfer in the fresh cycle, n (%)~ | |||

| Day 2 | 6 (4) | 9 (1) | 0.06 |

| Days 3 and 4 | 87 (58) | 543 (63.7) | |

| Days 5 and 6 | 57 (38) | 301 (35.3) | |

| Number of embryos transferred in the fresh cycle~ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1.5 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | < 0.001 |

| Fresh LBR | |||

| n (%) | 56 (35) | 331 (34) | 0.8 |

| Cumulative LBR | |||

| n (%) | 71 (44.4) | 475 (48.9) | 0.3 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Person χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (unadjusted)

~For patients having an embryo transfer (n = 1003)

Fig. 4.

Fresh and cumulative LBR according to the insemination method in normal (a) and high responders (b)

High responders

In total, 555 high responders were included. Among them, 468 (84%) had ICSI and 87 (16%) had IVF. Age, BMI, and AFC were similar between the two groups, while the cause of infertility differed significantly (Table 7). Patients who underwent ICSI had a significantly higher starting dose of stimulation compared with IVF patients (median (IQR)) (200 IU/day (150–225 vs. 150 IU/day (150–225), p value < 0.001) (Table 8). The duration of COS, the number of oocytes retrieved, the fertilization and embryo utilization rates, and the stage of ET in the fresh cycle was similar between the two groups. For the ICSI group: MII oocytes (median (IQR)) = 15 (12–18) and MR% (median (IQR)) = 78% (61–88). However, significantly, more embryos were transferred in the ICSI group (p value = 0.002). Fresh and cumulative LBR did not differ significantly for IVF and ICSI patients (145/468 (31%) vs. 32/87 (36.7%) and 287/468 (61.3%) vs. 52/87 (59.8%), p value = 0.3 and 0.8, respectively)) (Fig. 4).

Table 7.

Baseline characteristics of high responders (group D)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 87 (16%) | n = 468 (84%) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 34 (30–37) | 33 (30–37) | 0.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 22.4 (20.3–24.8) | 22.2 (20.4–24.7) | 0.9 |

| Infertility cause, n (%) | |||

| Endometriosis | 10 (11.5) | 36 (7.8) | 0.003 |

| PCOS | 23 (26.4) | 80 (17) | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 13 (15) | 81 (17.3) | |

| Tubal | 19 (21.8) | 59 (12.6) | |

| Unexplained | 22 (25.3) | 212 (45.3) | |

| AFC | 14 (17–18) | 15 (11–19) | 0.12 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Pearson’s chi-squared test (unadjusted)

Table 8.

Ovarian stimulation characteristics in high responders (group D)

| IVF | ICSI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 87 (15.7%) | n = 468 (84.3%) | ||

| Initial dose (IU) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 150 (150–225) | 200 (150–225) | 0.001 |

| Stimulation days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 0.45 |

| Number of oocytes | |||

| Median IQR | 19 (17–24) | 19 (17–22) | 0.9 |

| Fertilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 53.3 (35.3–69.6) | 55.7 (43.8–68.8) | 0.2 |

| Embryo utilization rates (%) | |||

| Median IQR | 50 (33.3–69.2) | 45.5 (29.4–66.6) | 0.64 |

| Day of embryo transfer in the fresh cycle, n (%)~ | |||

| Day 2 | 15 (20.8) | 59 (12.3) | 0.06 |

| Days 3 and 4 | 54 (75) | 375 (78) | |

| Days 5 and 6 | 3 (4.2) | 47 (9.7) | |

| Number of embryos transferred in the fresh cycle~ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 0.002 |

| Fresh LBR | |||

| n (%) | 32 (36.7) | 145 (31) | 0.3 |

| Cumulative LBR | |||

| n (%) | 52 (59.8) | 287 (61.3) | 0.8 |

Two-sample Mann–Whitney test or Person χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (unadjusted)

~For patients having an embryo transfer (n = 553)

Multivariable GEE regression analysis for fertilization rate

Results of the univariate GEE regression analyses are presented in Supplementary Table 1. After conducting GEE multivariate regression, the insemination method was not significantly associated with fertilization rate (coefficient = 0.02, p value = 0.45) (Table 9). The ovarian response group was the only predictor of fertilization rate (coefficient = − 0.12 ± 0.05, − 0.2 ± 0.06, − 0.024 ± 0.08 for groups B, C, and D, respectively, p value = 0.006).

Table 9.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression analysis for fertilization rates, taking into account the clustering for canters (adjusted)

| Coefficient ± SE* | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Insemination method | ||

| IVF | – | |

| ICSI | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.45 |

| Ovarian response | ||

| Group A | – | 0.006 |

| Group B | − 0.12 ± 0.05 | |

| Group C | − 0.2 ± 0.06 | |

| Group D | − 0.024 ± 0.08 | |

| Female age | − 0.004 ± 0.005 | 0.47 |

| BMI | − 0.003 ± 0.005 | 0.6 |

| Infertility cause | ||

| Endometriosis | – | 0.92 |

| PCOS | − 0.05 ± 0.09 | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 0.003 ± 0.07 | |

| Tubal | 0.03 ± 0.08 | |

| Unexplained | 0.01 ± 0.07 | |

*SE, standard error

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first and largest multinational analysis, specifically evaluating the effect of the insemination method for ART, based on the number of oocytes retrieved in women without male factor infertility. Based on our results, the oocyte yield should not play any role in the decision to choose either IVF or ICSI in COS cycles. Fertilization rates were comparable between groups. Furthermore, fresh and cumulative LBR were similar in different ovarian response categories, irrespective of the insemination method used.

Very few studies have addressed the issue of the optimal insemination technique used in ART [19]. Our results are in line with a large registry analysis from Latin America, suggesting that there is no advantage of ICSI over IVF in non-male factor infertility [8]. However, one of the main limitations of the aforementioned study is that several cycles performed by the same patient were included, implying a higher risk of selection bias, i.e., couples with the worst prognosis or patients with a history of fertilization failures may have undergone ICSI. In contrast, our study included exclusively the first cycle of all infertile women in order to eliminate, as much as possible, the risk of bias and accurately assess the effect of the insemination method on relevant reproductive outcomes. Furthermore, contrary to the previous study, we did not find any negative effect of ICSI in the odds of delivery, given that the fresh and cumulative LBR between the two insemination methods were comparable in all ovarian response categories. Again, selection biases may have played a crucial role in the findings of the previous study. Similarly, in another retrospective analysis evaluating the effect of ICSI in women 40–43 years old [7], the ICSI group had a higher number of patients with previous failed IVF attempts, which could justify the better outcomes in terms of number of mature oocytes, fertilization rates, and number of zygotes formed, observed in the IVF group. We failed to replicate these results, given that fertilization and embryo utilization rates were similar between IVF and ICSI, in each ovarian response group. An explanation could be that although ICSI may be related to a potential mechanical damage to the oocyte membrane and cytoplasm during the procedure [20], it is well established that ICSI requires a highly experienced laboratory.

The only study which evaluated cumulative LBR in patients undergoing IVF or ICSI reported similar outcomes between the two groups irrespective of female/male age and parity [21]. Nonetheless, the cause of infertility was not available for several patients included and the reported causes were based on clinician’s classification. Furthermore, residual bias may have occurred, given the absence of data on relevant confounders.

The strength of our study relies on its design. A very large sample size of infertile patients across 15 European ART centers was selected. Furthermore, we decided to include only the first cycle of these patients, in order to be able to precisely evaluate whether the association between the number of oocytes and the insemination method could affect the reproductive outcome. All women included in our analysis were treated with an antagonist protocol, contrary to the previous studies [7, 8, 21]. The rationale was to include a homogenous population and also be able to evaluate the impact of the insemination technique in patients with high ovarian response.

Despite the robust design of our study, limitations do exist and should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. The retrospective nature of our study is inherent to the risk of bias. Therefore, although a significant effort has been made to eliminate all known sources of systematic error through multivariable analysis, there might still exist non-apparent sources of bias. Firstly, patients were allocated to the two insemination techniques based on the physician’s discretion; hence, the ICSI group may have included women of poorer prognosis (as documented by the higher starting dose and number of embryos transferred in some of the ovarian response groups). Secondly, one may argue that our study included “good prognosis” women undergoing their first COS cycle. Therefore, firm conclusions cannot be drawn for patients with several previous failed IVF attempts, although there is no evidence supporting that ICSI could improve the results in these cases. Thirdly, the primary endpoint was fertilization rate and not fresh or cumulative LBR. However, the rationale for setting fertilization rate as the primary endpoint (and not fresh or cumulative LBR) was that several variables (confounders) might affect the relationship between the insemination method and fresh/cumulative LBR, impairing the validity of the comparisons. Finally, our population-based study lacks information on specific clinic protocols and processes for IVF and ICSI between the different centers.

In conclusion, for women undergoing their first COS cycle, the number of oocytes retrieved has no value for the selection of the insemination procedure in case of non-male infertility. The choice of the insemination method should be based exclusively on semen parameters. The added cost of ICSI should also be taken into account in the absence of male factor infertility. Further prospective and randomized studies are needed in order to validate our findings.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 53 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Walter Meul and Alfredo Navarro for their contribution to the data management of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/14/2019

The original article unfortunately contained 2 mistakes.

References

- 1.Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem AC. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet. 1992;340(8810):17–18. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, Wyns C, Mocanu E, Motrenko T, et al. ART in Europe, 2014: results generated from European registries by ESHRE: the European IVF-monitoring consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Hum Reprod. 2018;33(9):1586–1601. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulet SL, Mehta A, Kissin DM, Warner L, Kawwass JF, Jamieson DJ. Trends in use of and reproductive outcomes associated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. JAMA. 2015;313(3):255–263. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Chambers GM, Zegers-Hochschild F, Mansour R, Ishihara O, Banker M, Dyer S. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(6):1067–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Check JH, Yuan W, Garberi-Levito MC, Swenson K, McMonagle K. Effect of method of oocyte fertilization on fertilization, pregnancy and implantation rates in women with unexplained infertility. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(3):203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luna M, Bigelow C, Duke M, Ruman J, Sandler B, Grunfeld L, Copperman AB. Should ICSI be recommended routinely in patients with four or fewer oocytes retrieved? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28(10):911–915. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9614-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tannus S, Son WY, Gilman A, Younes G, Shavit T, Dahan MH. The role of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non-male factor infertility in advanced maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(1):119–124. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarze J, Jeria R, Crosby J, Villa S, Ortega O, Pommer R. Is there a reason to perform ICSI in the absence of male factor? Lessons from the Latin American Registry of ART. Human Reprod Open. 2017;2(2):1–5. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hox013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drakopoulos P, Blockeel C, Stoop D, Camus M, de Vos M, Tournaye H, Polyzos NP. Conventional ovarian stimulation and single embryo transfer for IVF/ICSI. How many oocytes do we need to maximize cumulative live birth rates after utilization of all fresh and frozen embryos? Hum Reprod. 2016;31(2):370–376. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polyzos NP, Drakopoulos P, Parra J, Pellicer A, Santos-Ribeiro S, Tournaye H, Bosch E, Garcia-Velasco J. Cumulative live birth rates according to the number of oocytes retrieved after the first ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multicenter multinational analysis including approximately 15,000 women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(4):661–70 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM, et al. World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(3):231–245. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp048.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papanikolaou EG, Pozzobon C, Kolibianakis EM, Camus M, Tournaye H, Fatemi HM, van Steirteghem A, Devroey P. Incidence and prediction of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in women undergoing gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humaidan P, Polyzos NP, Alsbjerg B, Erb K, Mikkelsen AL, Elbaek HO, Papanikolaou EG, Andersen CY. GnRHa trigger and individualized luteal phase hCG support according to ovarian response to stimulation: two prospective randomized controlled multi-centre studies in IVF patients. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(9):2511–2521. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L, et al. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polyzos NP, Sunkara SK. Sub-optimal responders following controlled ovarian stimulation: an overlooked group? Hum Reprod. 2015;30(9):2005–2008. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Embryology ESIGo, Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine Electronic address cbgi. The Vienna consensus: report of an expert meeting on the development of ART laboratory performance indicators. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35(5):494–510. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dang VQ, Vuong LN, Ho TM, Ha AN, Nguyen QN, Truong BT, Pham QT, Wang R, Norman RJ, Mol BW. The effectiveness of ICSI versus conventional IVF in couples with non-male factor infertility: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Hum Reprod Open. 2019;2019(2):hoz006. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoz006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, Rienzi L, Sunde A, Schmidt L, Cooke ID, Simpson JL, van der Poel S. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1786–1801. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rumste MM, Evers JL, Farquhar CM. Intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection versus conventional techniques for oocyte insemination during in vitro fertilisation in patients with non-male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD001301. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen MP, Shen S, Dobson AT, Fujimoto VY, McCulloch CE, Cedars MI. Oocyte degeneration after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multivariate analysis to assess its importance as a laboratory or clinical marker. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(6):1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Wang AY, Bowman M, Hammarberg K, Farquhar C, Johnson L, Safi N, Sullivan EA. ICSI does not increase the cumulative live birth rate in non-male factor infertility. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(7):1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 53 kb)