Abstract

The 1,2-diamine motif is widely present in natural products, pharmaceutical compounds, and catalysts used in asymmetric synthesis. The simultaneous introduction of two amino groups across an alkene feedstock is an appealing yet challenging approach for the synthesis of 1,2-diamines, primarily due to the inhibitory effect of the diamine products to transition metal catalysts and the difficulty in controlling reaction diastereoselectivity and regioselectivity. Herein we report a scalable electrocatalytic 1,2-diamination reaction that can be used to convert stable, easily available aryl alkenes and sulfamides to 1,2-diamines with excellent diastereoselectivity. Monosubstituted sulfamides react in a regioselective manner to afford 1,2-diamines bearing different substituents on the two amino groups. The combination of an organic redox catalyst and electricity not only obviates the use of any transition metal catalyst and oxidizing reagent, but also ensures broad reaction compatibility with a variety of electronically and sterically diverse substrates.

Subject terms: Chemical synthesis, Electrocatalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Methods to prepare 1,2-diamines are desirable due the importance of these compounds as drug scaffolds and organic ligands for metals. Here, the authors report an electrochemical metal-free 1,2- diamination of aryl alkenes with sulfamides to 1,2-diamines with excellent diastereoselectivity.

Introduction

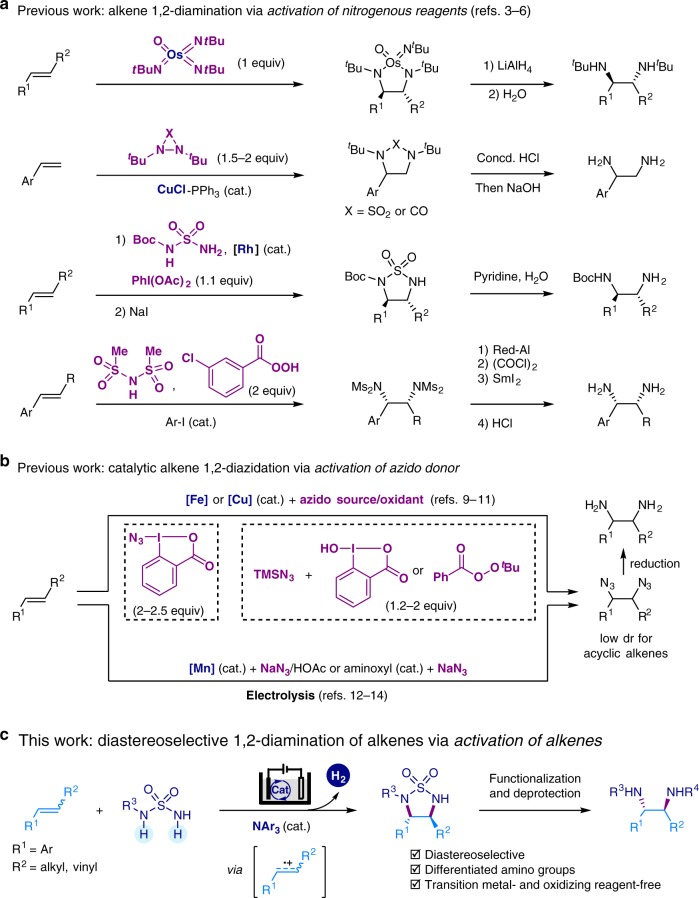

1,2-Diamine is a prevalent structural motif in natural products, pharmaceutical compounds, and molecular catalysts1. Alkene 1,2-diamination and 1,2-diazidation reactions are among the most straightforward and attractive strategies for 1,2-diamine synthesis, especially considering the easy accessibility and handling of alkene substrates2. Significant progress has been achieved over the past decades in alkene 1,2-diamination and 1,2-diazidation reactions, mainly through transition metal catalysis (Fig. 1a, b)3–18. Unfortunately, these methods are not without drawbacks. First, the use of stoichiometric amounts of transition metal reagents (e.g., osmium or cobalt)3,7, chemical oxidants (e.g., iodine (III) reagents or organic peroxides)5,6,10,11, or azide reagents8–14 raises cost, environmental, and safety issues, especially for large-scale applications19,20. Second, they are often limited in substrate scope, sometimes requiring special amination reagents (e.g., diaziridinone and its analogs4,15,16, or azido-iodine compounds9). Other challenges that need to be addressed include unsatisfactory diastereoselectivity for internal alkenes and poor differentiation of the two amino groups in the diamine products.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of 1,2-diamines. a, b Representative examples of established 1,2-diamine synthesis via vicinal difunctionalization of alkenes. c Proposed electrochemical 1,2-diamination of alkenes with sulfamides via dehydrogenative annulation and removal of the sulfonyl group. Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; Ms, methanesulfonyl; TMS, trimethylsilyl

Organic electrochemistry, which drives redox processes with electric current, is increasingly considered as a highly sustainable and efficient synthetic method21–34. One key advantage of using electrochemical methods is that the reaction efficiency and selectivity can often be boosted by manipulating the electric current or potential, allowing one to achieve transformations that are otherwise synthetically inaccessible. In this context, Yoshida35 reported isolated examples of alkene diamination through intramolecular trapping of alkene radical cations. Shäfer36 reported an early example of electrochemical 1,2-diazidation of simple alkenes with NaN3 in acetic acid. Lin and co-workers recently developed a NaN3-based electrocatalytic olefin 1,2-diazidiation reaction that showed an exceptional substrate scope and broad functional group compatibility (Fig. 1b, bottom)12–14.

Building on our experience with electrochemical alkene difunctionalization37,38, herein we report a diastereoselective electrocatalytic 1,2-diamination reaction of di- and tri-substituted alkenes using easily available and stable sulfamides as amino donors. A wide variety of 1,2-diamines, where the two amino groups are functionalized with different substituents, can be prepared via regio- and diastereoselective diamination using monosubstituted sulfamides. The electrosynthetic method employs an organic redox catalyst and proceeds through H2 evolution, while obviating the need for transition metal catalysts and external chemical oxidants.

Results

Design plan

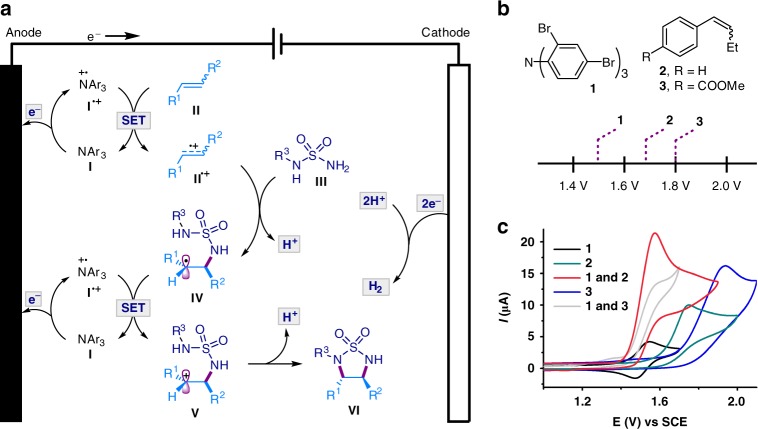

Inspired by our previously work on electrochemical alkene dioxygenation reactions38, we envisioned the trapping of an electrocatalytically generated alkene radical cation II•+ with a sulfamide III to generate a carbon radical IV (Fig. 2a).39–43 Single-electron transfer oxidation of IV by I•+ would produce a carbocation V, which could then undergo cyclization to afford the cyclic sulfamide VI. Cyclization of V has a key role in governing the stereoselectivity of the 1,2-diamination, in which the alkene-originated substituents R1 and R2 are positioned on opposite sides of the nascent five-membered ring to minimize steric repulsion. The electrons that the alkene loses to the anode would eventually combine with the protons at the cathode to form H2, thereby obviating the need for external electron and proton acceptors. The controlled formation of alkene radical cations at low concentrations is essential to overcome their strong propensity toward self-dimerization or reaction with the alkene precursors, especially on electrode surface44–46. This could be accomplished by conducting electrolysis indirectly in the presence of a redox catalyst rather than direct electrolysis. Measuring catalytic current through cyclic voltammetry33,47, with tris(2,4-dibromophenyl)amine (1, Ep/2 = 1.48 V vs saturated calomel electrode (SCE)) as the redox catalyst, confirmed the facile electrocatalytic oxidation of the alkenes 2 (Ep/2 = 1.66 V vs SCE) and 3 (Ep/2 = 1.80 V vs SCE) that bears an electron-withdrawing ester group (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Proposed reaction design. a The proposed reaction mechanism. The process combines anodic oxidation and cathodic proton reduction to achieve the alkene 1,2-diamination via H2 evolution. The electrocatalytic activation of the alkene through single-electron transfer (SET) oxidation generates the alkene radical cation II•+, which is trapped by the sulfamide III to give radical IV. Further SET oxidation and diastereoselective cyclization of V afford diamination product VI. The cathode reduces protons to generate H2. b Oxidation potentials [Ep/2 vs Saturated calomel electrode (SCE)] of triarylamine 1 and alkenes 2 and 3. c Cyclic voltammetry. The studies show that triarylamine 1 can catalyze the oxidation of aryl alkenes 2 and 3

Reaction optimization

The 1,2-diamination of aryl alkene 2 with sulfamide 4 was chosen as a model reaction for optimizing the electrochemical conditions. The electrolysis was conducted at RT and at a constant current in a three-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with a reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) anode and a platinum plate cathode. The optimal reaction system consisted of triarylamine 1 (10 mol %) as redox catalyst, iPrCO2H (2 equiv) and BF3•Et2O (0.5 equiv) as additives, Et4NPF6 as supporting electrolyte to increase conductivity, and MeCN/CH2Cl2 (1:2) as solvent. Under these conditions, the diamination product 5 was obtained in 72% yield with excellent diastereoselectivty ( > 20:1 dr) even though a starting mixture of Z/E isomers of 2 was used (in a ratio of 5.6:1) (Table 1, entry 1). Independent reaction using a pure E- or Z-isomer of 2 afforded the same trans diastereomer 5 in 65% and 69% yield, respectively. Similar results could also be obtained when the reaction was performed in ElectraSyn 2.0, a commercial apparatus (Table 1, entry 2). The use of MeCN as solvent instead of MeCN/CH2Cl2 resulted in a lower yield of 50% (Table 1, entry 3). Other triarylamine derivatives such as 6 (Ep/2 = 1.06 V vs SCE), 7 (Ep/2 = 1.26 V vs SCE), and 8 (Ep/2 = 1.33 V vs SCE) were found to be less effective in promoting the formation of 5 probably because of their lower oxidation potentials (Table 1, entries 4–6). Control experiments showed that the triarylamine catalyst (Table 1, entry 7), iPrCO2H (Table 1, entry 8) and BF3•Et2O (Table 1, entry 9) were all indispensable for achieving optimal reaction efficiency. Replacing iPrCO2H with AcOH (Table 1, entry 10) or CF3CO2H (Table 1, entry 11) led to a slight yield reduction. The yield of 5 dropped to 20% in the absence of iPrCO2H and BF3•Et2O (Table 1, entry 12). On the other hand, substituting HBF4 (0.5 equiv) for both iPrCO2H and BF3•Et2O rescued the formation of 5 to a significant extent (Table 1, entry 13). We speculated that iPrCO2H and BF3•Et2O could complex to form a stronger protic acid, which is helpful for cathodic proton reduction and thus avoiding unwanted reduction of the substrates or products48.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditionsa

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Deviation from standard conditions | Yield of 5 (%)b |

| 1 | None | 72c |

| 2 | Reaction conducted using ElectraSyn 2.0 | 74 |

| 3 | MeCN as solvent | 50 |

| 4 | (4-BrC6H4)3N (6) as the catalyst | 16 |

| 5 | (4-MeO2CC6H4)3N (7) as the catalyst | 51 |

| 6 | (2,4-Br2-C6H3)2N(4-Br-C6H4) (8) as the catalyst | 52 |

| 7 | No 1 | 23 |

| 8 | No iPrCO2H | 58 |

| 9 | No BF3•Et2O | 46 |

| 10 | AcOH instead of iPrCO2H | 65 |

| 11 | CF3CO2H instead of iPrCO2H | 67 |

| 12 | No iPrCO2H and BF3•Et2O | 20 |

| 13 | HBF4 (0.5 equiv) instead of iPrCO2H and BF3•Et2O | 66 |

aReaction conditions: RVC (100 PPI, 1 cm × 1 cm × 1.2 cm), Pt plate cathode (1 cm × 1 cm), 2 (0.2 mmol), 4 (0.4 mmol), MeCN (2 mL), CH2Cl2 (4 mL), Et4NPF6 (0.2 mmol), 12.5 mA (janode = 0.16 mA cm−2), 0.9 h (2.2 F mol–1)

bDetermined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard

cIsolated yield

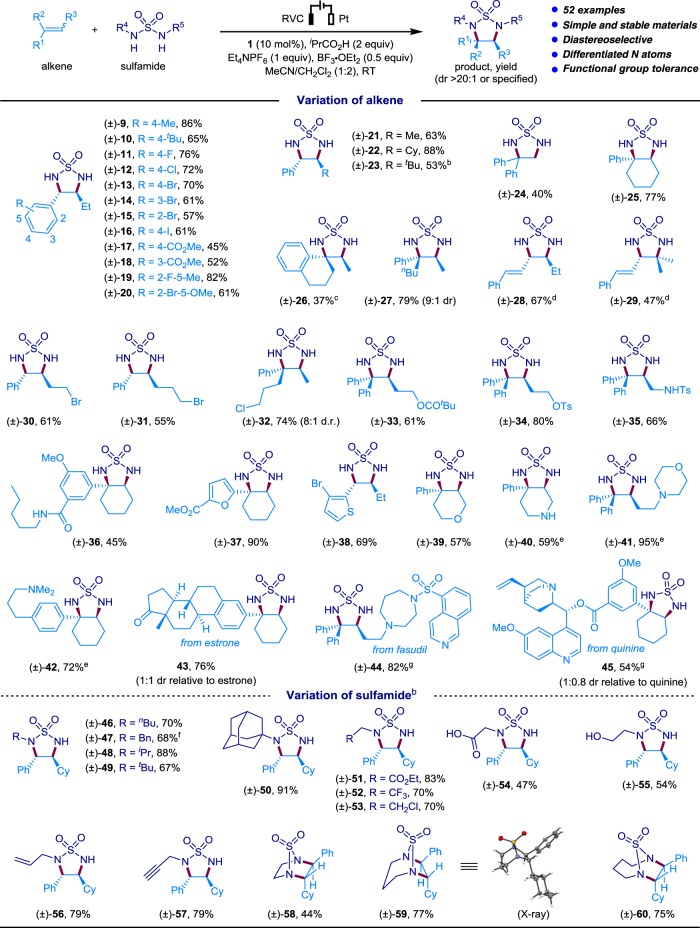

Evaluation of substrate scope

We next explored the scope of alkenes by using sulfamide 4 as the coupling partner (Table 2). The aryl ring in the 1,2-disubstituted alkene could be functionalized with an electronically diverse set of substituents, including Me (9), tBu (10), halogens (F, Cl, Br, I; 11–16), and ester (17 and 18), at various positions of the phenyl ring. Alkenes carrying a 2,5-disubstituted phenyl ring were also found to be suitable substrates (19 and 20). The β-position of the styrenyl alkene showed broad tolerance for alkyl substituents of different sizes, such as Me (21), cyclohexyl (Cy; 22), and tBu (23). Terminal alkenes were less-efficient substrates probably owing to the facile dimerization/oligomerization of these alkenes44,49. As an example, the reaction of 1,1-diphenylethylene with 4 afforded the desired product 24 in 40% yield. One the other hand, tri-substituted cyclic (25) and acyclic (26 and 27) alkenes reacted smoothly to afford the corresponding cyclic sulfamides in good to excellent diastereoselectivity. Meanwhile, 1,2-diamination of 1,3-dienes showed satisfactory regioselectivity in favor of the alkenyl moiety distal to the phenyl group (28 and 29). Note that triarylamine 6 was employed as redox catalyst to overcome the relatively low oxidation potentials of 1,3-dienes (Ep/2 = 1.29 V vs SCE) and avoid oxidizing the remaining alkene moiety in the products. Furthermore, the electrochemical alkene 1,2-diamination reaction was compatible with alkylbromide (30 and 31), alkylchloride (32), ester (17, 18, 33), sulfonic ester (34), sulfonamide (35), amide (36), heterocycles such as furan (37) and thiophene (38), cyclic ether (39), and even oxidation-labile secondary and tertiary amines (40–42). Alkenes derived from estrone (43), fasudil (44), and quinine (45) reacted with similar success. The electron-rich amino groups in the cases of 40–42, 44, and 45 were masked as ammonium salts by the addition of HBF4 to prevent oxidative decomposition.

Table 2.

Substrate scopea

aReaction conditions: alkene (0.2 mmol), sulfamide (0.4 mmol), 0.9–3.7 h (2.0–8.7 F mol−1). All yields are isolated yields

bReaction with sulfamide (1.2 mmol) and BF3•OEt2 (0.2 mmol)

cReaction without BF3•OEt2

dReaction with 6 (10 mol %) as the catalyst

eReaction with HBF4 (0.3 mmol) instead of BF3•OEt2

fReaction with sulfamide (0.8 mmol) and BF3•OEt2 (0.2 mmol)

gReaction with HBF4 (0.4 mmol) instead of BF3•OEt2. Cy, cyclohexyl; Ts, tosyl

The electrochemical method also proved capable of generating 1,2-diamine products that carry two differently decorated amino groups, or cyclic 1,2-diamines (Table 2). For example, we succeeded in the 1,2-diamination with a wide array of asymmetric sulfamides bearing a single alkyl group on one of its nitrogen atoms. In these cases, the alkyl substituent could be primary (46, 47), secondary (48), tertiary (49, 50), or functionalized with ester (51), CF3 (52), alkylchloride (53), carboxylic acid (54), free alcohol (55), alkene (56), or alkyne (57). These asymmetric sulfamides reacted in a strictly regioselective manner. Notably, bridged bicyclic products (58–60) could be obtained by 1,2-diamination of cyclic sulfamide substrates. The structure of 59 was further confirmed by single crystal X-ray analysis.

Gram scale synthesis and product transformations

To further demonstrate the synthetic utility of our electrochemical method, we reacted alkene 61 or 62 with sulfamide 4, 63, or 64 on gram or even decagram scale and obtained the corresponding products (21, 22, 48, and 59) in good yields (Fig. 3). Deprotection of theses cyclic sulfamides with HBr or hydrazine furnished diamines 65–67, 69, and 70. Protection of the free amino group in 67 with Boc2O resulted in the formation of 68, whose two amino groups carries different substituents and therefore is amenable to further chemoselective derivatization. On the other hand, 48 could be converted to diamine 69, also with differently decorated amino groups, through methylation and subsequent sulfonyl removal.

Fig. 3.

Gram scale synthesis and further product transformations. Gram scale synthesis of compounds 21, 22, 48, and 59, and their conversion to amines

Methods

Representative procedure for the synthesis of 5

To a 10-mL three-necked round-bottomed flask were added sulfamide 4 (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv), triarylamine 1 (0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv) and Et4NPF6 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv). The flask was equipped with an RVC anode (100 PPI, 1 cm × 1 cm × 1.2 cm) and a platinum plate (1 cm × 1 cm) cathode. After flushing the flask with argon, MeCN (2 mL), CH2Cl2 (4 mL), alkene 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), iPrCO2H (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv) and BF3˙Et2O (0.1 mmol, 0.5 equiv) were added sequentially. The constant current (12.5 mA) electrolysis was carried out at room temperature until complete consumption of 2 (monitored by TLC or 1H NMR). Saturated NaHCO3 solution was added. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic solution was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was separated by silica gel chromatography and the product 5 obtained in 72% yield by eluting with ethyl acetate/hexanes. All new compounds were fully characterized (See the Supplementary Methods).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support of this research from MOST (2016YFA0204100), NSFC (No. 21672178), Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author contributions

C.Y.C. and X.M.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. H.C.X. designed and directed the project and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1938821 (59). The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre [http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif]. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary information files. Any further relevant data are available from the authors on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-13024-5.

References

- 1.Lucet D, Le Gall T, Mioskowski C. The chemistry of vicinal diamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2580–2627. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2580::AID-ANIE2580>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardona F, Goti A. Metal-catalysed 1,2-diamination reactions. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:269–275. doi: 10.1038/nchem.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong AO, Oshima K, Sharpless KB. Synthesis of dioxobis(tert-alkylimido)osmium(VIII) and oxotris(tert-alkylimido)osmium(VIII) complexes. Stereospecific vicinal diamination of olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:3420–3426. doi: 10.1021/ja00452a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Cornwall RG, Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. Catalytic diamination of olefins via N–N bond activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3665–3678. doi: 10.1021/ar500344t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson DE, Su JY, Roberts DA, Du Bois J. Vicinal diamination of alkenes under Rh-catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13506–13509. doi: 10.1021/ja506532h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muñiz K, Barreiro L, Romero RM, Martínez C. Catalytic asymmetric diamination of styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4354–4357. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker PN, White MA, Bergman RG. A new method for 1,2-diamination of alkenes using cyclopentadienylnitrosylcobalt dimer/NO/LiAlH4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5676–5677. doi: 10.1021/ja00537a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang B, Studer A. Copper-catalyzed intermolecular aminoazidation of alkenes. Org. Lett. 2014;16:1790–1793. doi: 10.1021/ol500513b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fumagalli G, Rabet PTG, Boyd S, Greaney MF. Three-component azidation of styrene-type double bonds: light-switchable behavior of a copper photoredox catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11481–11484. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Y-A, Lu D-F, Chen Y-R, Xu H. Iron-catalyzed direct diazidation for a broad range of olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:534–538. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen S-J, Zhu C-L, Lu D-F, Xu H. Iron-catalyzed direct olefin diazidation via peroxyester activation promoted by nitrogen-based ligands. ACS Catal. 2018;8:4473–4482. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu N, Sauer GS, Saha A, Loo A, Lin S. Metal-catalyzed electrochemical diazidation of alkenes. Science. 2017;357:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu N, Sauer GS, Lin S. A general, electrocatalytic approach to the synthesis of vicinal diamines. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:1725–1743. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siu JC, Parry JB, Lin S. Aminoxyl-catalyzed electrochemical diazidation of alkenes mediated by a metastable charge-transfer complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:2825–2831. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao B, Yuan W, Du H, Shi Y. Cu(I)-catalyzed intermolecular diamination of activated terminal olefins. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4943–4945. doi: 10.1021/ol702061s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen Y, Zhao B, Shi Y. Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of disubstituted terminal olefins: an approach to potent NK1 antagonist. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2365–2368. doi: 10.1021/ol900808z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrams R, Lefebvre Q, Clayden J. Transition metal free cycloamination of prenyl carbamates and ureas promoted by aryldiazonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:13587–13591. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies J, Sheikh NS, Leonori D. Photoredox imino functionalizations of olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:13361–13365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caron S, Dugger RW, Ruggeri SG, Ragan JA, Ripin DH. Large-scale oxidations in the pharmaceutical industry. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2943–2989. doi: 10.1021/cr040679f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu H-T, Arosio L, Villa R, Nebuloni M, Xu H. Process safety assessment of the iron-catalyzed direct olefin diazidation for the expedient synthesis of vicinal primary diamines. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2017;21:2068–2072. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horn EJ, Rosen BR, Baran PS. Synthetic organic electrochemistry: an enabling and innately sustainable method. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016;2:302–308. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan M, Kawamata Y, Baran PS. Synthetic organic electrochemical methods since 2000: on the verge of a renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:13230–13319. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y, Xu K, Zeng C. Use of electrochemistry in the synthesis of heterocyclic structures. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4485–4540. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohle S, et al. Modern electrochemical aspects for the synthesis of value-added organic products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:6018–6041. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anton W, et al. Electrifying organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5594–5619. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang S, Liu Y, Lei A. Electrochemical oxidative cross-coupling with hydrogen evolution: a green and sustainable way for bond formation. Chem. 2018;4:27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida J-i, Shimizu A, Hayashi R. Electrogenerated cationic reactive intermediates: the pool method and further advances. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4702–4730. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moeller KD. Using physical organic chemistry to shape the course of electrochemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4817–4833. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauermann N, Meyer TH, Qiu Y, Ackermann L. Electrocatalytic C–H Activation. activation. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7086–7103. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma C, Fang P, Mei T-S. Recent advances in C–H functionalization using electrochemical transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7179–7189. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kärkäs MD. Electrochemical strategies for C–H functionalization and C–N bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:5786–5865. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00619E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nutting JE, Rafiee M, Stahl SS. Tetramethylpiperidine N-oxyl (TEMPO), phthalimide N-oxyl (PINO), and related N-oxyl species: electrochemical properties and their use in electrocatalytic reactions. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4834–4885. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francke R, Little RD. Redox catalysis in organic electrosynthesis: basic principles and recent developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:2492–2521. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60464k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye Z, Zhang F. Recent advances in constructing nitrogen-containing heterocycles via electrochemical dehydrogenation. Chin. J. Chem. 2019;37:513–528. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201900049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morofuji T, Shimizu A, Yoshida J. Direct C-N coupling of imidazoles with aromatic and benzylic compounds via Electrooxidative C-H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4496–4499. doi: 10.1021/ja501093m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shäfer H. Oxidative addition of the azide ion to olefine, a simple route to diamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1970;9:158–159. doi: 10.1002/anie.197001582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong P, et al. Electrochemically enabled carbohydroxylation of alkenes with H2O and organotrifluoroborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:16387–16391. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai C-Y, Xu H-C. Dehydrogenative reagent-free annulation of alkenes with diols for the synthesis of saturated O-heterocycles. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3551. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monos TM, McAtee RC, Stephenson CRJ. Arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents for alkene aminoarylation. Science. 2018;361:1369. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margrey KA, Nicewicz DA. A general approach to catalytic alkene anti-markovnikov hydrofunctionalization reactions via acridinium photoredox catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:1997–2006. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng R, Smith JA, Moeller KD. Anodic cyclization reactions and the mechanistic strategies that enable optimization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:2346–2352. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, et al. Electrochemical aziridination by alkene activation using a sulfamate as the nitrogen source. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5695–5698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi H, et al. Photocatalytic Dehydrogenative cross-coupling of alkenes with alcohols or azoles without external oxidant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:1120–1124. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnston LJ, Schepp NP. Reactivities of radical cations: characterization of styrene radical cations and measurements of their reactivity toward nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6564–6571. doi: 10.1021/ja00068a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgbacher G, Schaefer HJ, Roe DC. Kinetics of the anodic dimerization of 4,4’-dimethoxystilbene by the rotating ring-disk electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:7590–7593. doi: 10.1021/ja00519a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imada Y, Okada Y, Noguchi K, Chiba K. Selective functionalization of styrenes with oxygen using different electrode materials: olefin cleavage and synthesis of tetrahydrofuran derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:125–129. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steckhan E. Indirect electroorganic syntheses - a modern chapter of organic electrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1986;25:683–701. doi: 10.1002/anie.198606831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heaney, H. Boron trifluoride–acetic acid. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (2001), 10.1002/047084289X.rb246.

- 49.Wilger DJ, Grandjean J-MM, Lammert TR, Nicewicz DA. The direct anti-Markovnikov addition of mineral acids to styrenes. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:720. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1938821 (59). The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre [http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif]. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary information files. Any further relevant data are available from the authors on request.