Abstract

Objective:

Prior research has revealed a link between peer victimization and somatic complaints in healthy youth; however, the peer victimization experiences of youth with clinically significant chronic pain have not been examined. This study aims to determine rates of peer victimization among youth seeking treatment for chronic pain and to compare these rates to a community control group. Relationships between peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and functional disability are also examined.

Method:

One hundred forty-three adolescents (70 with chronic pain) completed measures assessing their experience of traditional (physical, relational, reputational) and cyber-based peer victimization, as well as measures assessing their depressive symptoms and pain-related functional disability.

Results:

Peer victimization experiences were common among youth with and without chronic pain. Within the chronic pain group, there were differences in rates of peer victimization as a function of the adolescent’s school setting. Adolescents with chronic pain attending traditional schools reported more frequent peer victimization experiences than adolescents with pain not enrolled in school or attending online/home school. Within the chronic pain sample, peer victimization was moderately associated with depressive symptoms and functional disability. Tests of a simple mediation model revealed a significant indirect effect of peer victimization on functional disability, through depression.

Conclusions:

These results are the first to systematically document the peer victimization experiences of adolescents with chronic pain. Peer victimization is commonly experienced, particularly for those enrolled in traditional school settings. Associations with depressive symptoms and functional disability suggest that peer victimization may be a useful target for intervention.

Keywords: adolescents, chronic pain, depression, disability, peer victimization

Chronic pain is a common experience throughout childhood and adolescence, with up to 40% of youth reporting persistent or recurrent pain of at least three months duration (King et al., 2011). Prevalence rates increase during mid-to-late adolescence, with a notable proportion of youth experiencing pain that is both intense and disabling (Huguet & Miró, 2008; von Baeyer, 2011). Such chronic pain is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including impairment in emotional, academic, and social domains (see Dick & Pillai Riddell, 2010; Forgeron et al., 2010; Palermo, 2000 for reviews).

To date, much of the research on the social functioning of youth with chronic pain has focused on pain’s impact within the family; however, a growing body of research has begun to examine other important relationships within adolescents’ social networks, including their peer relationships (Fales & Forgeron, 2014). In a seminal review, Forgeron and colleagues (2010) found preliminary evidence that children and adolescents with chronic pain have fewer reciprocated friendships, are more isolated, and may be subject to greater peer victimization compared with otherwise healthy youth. For example, in one early study, Greco, Freeman, and Dufton (2007) found that schoolchildren with recurrent abdominal pain were more likely to be rated by their classmates as victims of peer aggression compared to their peers without pain. In that study, peer victimization also uniquely contributed to negative academic and social outcomes, especially for children experiencing the highest levels of pain and peer victimization. These findings provide preliminary evidence that youth with pain may be at especial risk for peer victimization, and that victimization can have a significant impact on their general functioning.

Traditionally, peer victimization has been defined as being the target of harmful and aggressive acts perpetrated by a peer or peers (Finkelhor, 2008), and includes direct acts of physical aggression and threats of violence, as well as more indirect forms of relational and reputational aggression (i.e., social exclusion and rumor spreading; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Recently, there has been growing interest in cyber-victimization, or acts of peer-based aggression (threats, insults, harassment, and exclusion) that take place via information and communication technologies, including texts, emails, and social media postings (Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, 2014). Research investigating peer victimization has consistently shown that it is commonly experienced by youth and can have long-lasting and damaging effects on mental health and well-being (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). In addition, several large-scale community studies have linked cyber and traditional forms of peer victimization, prospectively and concurrently, to a wide range of somatic complaints, including headache, nausea, abdominal, and back pain (Fekkes, Pijpers, Fredriks, Vogels, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 2006; Gini & Pozzoli, 2013; Herge, La Greca, & Chan, 2016; Kowalski & Limber, 2013).

Research examining peer victimization in clinical samples of youth with chronic pain is extremely limited. In a notable exception, Simons, Logan, Chastain, and Stein (2010) found no association between peer victimization and pain-related outcomes among adolescents seeking treatment for chronic pain. Importantly, the brief measure used to assess peer victimization in that study emphasized direct acts of physical aggression, with relatively minimal assessment of the indirect forms of aggression most commonly experienced during adolescence. This is an important distinction because rates of physical aggression tend to decline with age, as children become more cognitively sophisticated and physical aggression becomes less socially acceptable (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006). In contrast, relational, reputational, and cyber forms of victimization increase through early adolescence, peaking during the transition from middle to high school, but remaining elevated during the high school years (Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel, 2009; Young, Boye, & Nelson, 2006). Thus, it is possible that the failure to find a link between peer victimization and impairment in Simons et al.’s (2010) study may have been the result of a misspecification or measurement issue, rather than a true lack of association (Cornell, Sheras, & Cole, 2006; Hymel & Swearer, 2015). To date, no study has comprehensively investigated indirect forms of peer victimization in youth seeking treatment for chronic pain, nor has any study systematically examined cyber-victimization experiences in this population. A broader assessment of these more subtle, yet equally pernicious, forms of victimization will provide a clearer picture of their links to functioning within this clinical population.

The primary aim of this study is to establish rates of self-reported peer victimization in youth seeking treatment for chronic pain, and to determine whether rates of perceived victimization are higher in this group compared to a community sample without chronic pain. Youth with chronic pain may experience a complex set of risk factors that increase their likelihood for peer victimization both on and offline. For example, depression and social isolation are associated with increased risk of peer victimization in general youth samples (e.g., Kochel, Ladd, & Rudolph, 2012; Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall, & Duku, 2013) and are elevated in youth with chronic pain (Kashikar-Zuck, Goldschneider, Powers, Vaught, & Hershey, 2001; Tegethoff, Belardi, Stalujanis, & Meinlschmidt, 2015). Thus, it was expected that youth with chronic pain may endorse (or perceive) more frequent peer victimization than their peers without pain.

Previous studies have not considered whether the type of school environment is associated with peer relationship problems for youth with chronic pain. Many youth with chronic pain do not regularly attend traditional school (Logan, Simons, Stein, & Chastain, 2008; Roth-Isigkeit, Thyen, Stoven, Schwarzenberger, & Schmucker, 2005), which is the primary setting for peer victimization experiences (Turner, Finkelhor, Hamby, Shattuck, & Ormrod, 2011). Consideration of school setting may yield important information about the experience of peer victimization within clinical samples. Further, though school is the primary setting for all forms of victimization, a unique feature of cyber-victimization is that it commonly occurs outside of that setting. As such, youth with chronic pain may be at greater risk for experiencing this form of victimization relative to the more traditional forms. An exploratory aim of this study is to evaluate whether there are differences in peer victimization rates as a function of school setting, including whether there are differences in rates of traditional compared with cyber forms of victimization. Because of limited contact with peers, it was expected that rates of victimization would be lowest among adolescents with pain who are not enrolled in traditional school settings (i.e., who are attending online or home-based schools or have withdrawn) and that youth with chronic pain attending traditional schools would be most at risk for each type of victimization.

The secondary aim is to determine whether perceived peer victimization experiences contribute to functional disability among youth with chronic pain, and whether depression mediates this relationship. In general samples, peer victimization is associated with increased rates of depression; thus, it was hypothesized the same would be true for youth with chronic pain. Because of the robust association between depression and disability in chronic pain samples (Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2001), it was hypothesized that depressive symptoms and pain-related disability would be positively correlated. It was further expected that peer victimization would be associated with disability, and that relationship would be explained by depression. Strategies for managing peer relationship problems are generally not included in standard interventions for pediatric chronic pain; should peer victimization emerge as a factor contributing to depression or functional disability, it suggests a new and meaningful target for interventions.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Seattle Children’s Research Institute served as the central IRB, with primary responsibility for reviewing and approving this study. Data were collected as part of a broader study that includes prospective diary monitoring of peer-based stressors; only the baseline data are reported in this study. Participants and their parents provided informed consent and/or assent prior to participating in any research activity. Enrolled participants included 74 adolescent pain patients recruited through two pediatric specialty pain clinics in the Pacific Northwest and 83 adolescents recruited from the community. Participants were recruited during four academic semesters (Spring 2014 through Fall 2015). Adolescents with chronic pain were contacted via phone or mail by study staff following their appointment with the pain clinic. Adolescents without chronic pain were recruited through Internet postings and flyers distributed throughout local communities. Adolescents and their parents who expressed interest in the study were screened for eligibility via telephone. Study eligibility criteria for the chronic pain group included (a) age between 14 and 18, (b) English-speaking, (c) reliable Internet access, (d) living at home with parent or legal guardian, (e) not enrolled in college, (f) weekly pain ≥3 months duration that interferes with daily activities, (g) no history of or current major comorbid medical illness (e.g., cancer, diabetes, sickle cell anemia), and (h) no serious mental health concern or recent psychiatric hospitalization. Study eligibility criteria for the adolescents without chronic pain were identical, with the exception that adolescents in this group were excluded if they had a history of chronic pain or were currently experiencing weekly pain ≥3 months duration.

Following initial screening, eligible participants and their parents were provided with a copy of the informed consent document and approximately one week later participated in a consent conference via telephone. Survey measures were completed online via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Harris et al., 2009) hosted at the University of Washington. Adolescents received compensation in the form of a $20 electronic gift card for completion of the baseline assessment. All data collection occurred during the academic year.

Ten adolescents enrolled from the community were excluded from the final analysis because they endorsed pain of moderate or higher intensity (a 4 on a 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale; NRS) at least once a week for the past three months with associated disability (endorsing pain-related impairment 50 on a visual analog scale of 0 to 100). Four adolescents seeking treatment for chronic pain were similarly excluded from the final analysis for not meeting the research definition of chronic pain (i.e., reported pain less than 1x/week for the past 3 months and pain did not significantly interfere with functioning).

Measures

Demographics and academic history.

Adolescents completed a demographic questionnaire assessing their gender, age, race/ethnicity, and parental education level. They also provided information regarding the type of school setting in which they were currently enrolled from a drop-down menu with seven options (public school, private day school, boarding school, alternative school, online school, home-school, or not enrolled). Individuals who endorsed attending school online or at home (n = 12) or who indicated that they were not enrolled (n = 8) were categorized as ‘nontraditional’ students (n = 20). All other responses were categorized as ‘traditional’ students (n = 49, chronic pain; n = 72, community). One participant in each group had missing data on this variable and thus were not included in exploratory subgroup analyses.

Pain history.

A pain history questionnaire was used to assess pain experiences over the past three months. Participants provided information regarding their primary pain location, its frequency, duration, and their pain-related distress (1–5 NRS, with anchors of 1 not at all and 5 very much). Participants also reported their usual pain intensity on an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS-11) with anchors of 0 (no pain) and 10 (worst pain imaginable; von Baeyer et al., 2009).

Functional disability.

The Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI) self-report version (Palermo, Lewandowski, Long, & Burant, 2008) was used to assess pain-related functional disability. This is a 21-item questionnaire, on which participants report their difficulty engaging in certain activities due to pain, with response options ranging from 0 (not very difficult) to 4 (extremely difficult). A “not applicable” option is also available. A total score is calculated by summing all of the valid item values. The CALI is a well-established measure with strong psychometric properties (Palermo et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was excellent (α = .94).

Traditional peer victimization.

The Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (R-PEQ; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001) was used to assess traditional peer victimization in the form of relational (i.e., social exclusion, “a peer did not invite me to a party or social event even though they knew that I wanted to go,”), reputational (i.e., rumor spreading, “another peer gossiped about me so others would not like me), and overt (i.e., physical, “a peer hit, kicked, or pushed me in a mean way”) aggression toward the participants (3 items/ subscale). Participants were instructed to report how often they were victimized within the past year, with options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (a few times a week).

Peer victimization can be conceptualized as a categorical or a continuous variable, in part depending upon the goals of the study (Underwood & Card, 2013). Researchers determining prevalence estimates tend to utilize a relatively straightforward categorical approach (e.g., Selkie, Fales, & Moreno, 2016), whereas those interested in identification of risk and protective factors tend to utilize a continuous approach (e.g., Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010). As the study aims to establish prevalence rates and evaluate associations between peer victimization and adjustment, scoring on the peer victimization measures is performed in two ways. First, within each subscale, individuals endorsing any item as having occurred “a few times or more” in the past year were categorized as victims. Experiencing repeated instances of peerbased aggression (i.e., more than once or twice) is thought to meaningfully distinguish between victims and nonvictims (see Solberg & Olweus, 2003). Although this is a generally accepted standard in the traditional peer victimization literature, a more conservative approach to identifying victims may offer more clinical value. Thus, a category for frequent victims was also created to categorize those endorsing any item as having occurred “weekly or more frequently” (see also Borowsky, Taliaferro, & McMorris, 2013). Finally, consistent with the standard scoring of this measure, items within each of the subscales were averaged to compute continuous relational, reputational, and overt peer victimization scores (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004). The R-PEQ was designed to be a developmentally appropriate measure of peer victimization for adolescents; it has good reliability, a stable factor structure, and has shown convergent validity with other established measures of peer victimization (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004; La Greca & Harrison, 2005). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was good for the relational (α = .89), reputational (α = .90), and overt victimization scales (α = .84).

Cyber-victimization.

Cyber-victimization experiences were assessed using two measures. The Social Networking Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Landoll, La Greca, & Lai, 2013) is a 10-item questionnaire developed to be used in conjunction with the R-PEQ. It assesses the frequency of peer victimization that occurs via social networking sites and electronic text messaging (i.e., “I found out that I was excluded from a party or event over a social networking site. . .,” “a peer sent me a mean message by text messaging”). Participants were instructed to report on their victimization experiences within the past year, with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (a few times a week). As described above, both categorical and continuous scoring approaches were used. Individuals endorsing any item as having occurred “a few times or more” in the past year were categorized as victims, and those endorsing any item as having occurred “weekly or more frequently” were categorized as frequent victims. Although it is common in the cyber-victimization literature to identify victims on the basis of endorsing any single item at least once (see Selkie et al., 2016), we use the same dichotomization scheme for the traditional and cybervictimization measures to allow for meaningful comparisons across the different forms of victimization (Wang et al., 2009). Finally, consistent with the standard scoring of this measure, items were averaged to create a continuous cybervictimization score. The SN-PEQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including a single-factor structure, evidence of measure invariance, and good convergent validity (Landoll et al., 2013). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was adequate (α = .78).

The victimization subscale of the Cyber Experiences Questionnaire (Huang & Chou, 2010) assesses the frequency of experiencing emotional distress as a result of peer aggression perpetrated via electronic media, including texting and social media sites. Four items assess cybervictimization distress more generally (i.e., “have you ever been harassed, hurt emotionally, or threatened online?”), whereas the remaining items assess cybervictimization distress experienced via distinct platforms (e.g., “Have you ever been hurt emotionally through cell phone text messages?”). Participants were instructed to report on their electronic victimization experiences within the past year, with response options ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (several times a week). Individuals endorsing any item as having occurred “several times a month” or more in the past year were categorized as victims, and those endorsing any item as having occurred “once a week” or more frequently were categorized as frequent victims. In addition, continuous scores were calculated by averaging the 10 items assessing cybervictimization distress. The measure has demonstrated strong reliability and face validity (Huang & Chou, 2010); Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was good (α = .88).

Depressive symptoms.

The 10-item depression subscale of the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita, Yim, Moffitt, Umemoto, & Francis, 2000) was used to measure symptoms of depression. This scale is a well-established screening tool for depression with strong evidence of reliability and convergent validity (Chorpita et al., 2000). Participants were asked to report on the frequency with which they experience common biological, cognitive, and affective symptoms of depression, with response options ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Scores were averaged to obtain a mean depression score. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was excellent (α = .92).

Data Analysis

All data were evaluated for normality, outliers, and accuracy in entry prior to performing analyses. Because of positive skew and evidence of kurtosis within the peer victimization variables, a square root transformation was applied (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007); following the transformation, skewness and kurtosis were within acceptable limits (all skew 3, kurtosis, 10; Kline, 2011). Subsequent analyses utilizing the continuous approach were conducted using the transformed variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.

First, traditional and cyber peer victimizations status was estimated for the total sample and by group status following the procedures outlined in the previous section. Chi-square analyses were used to test for difference in prevalence rates between the two groups. These analyses were repeated for the exploratory subgroup analyses to determine differences in peer victimization experiences by group status (chronic pain vs. community) and school setting (traditional vs. nontraditional). Only three groups were formed for the subgroup analyses, as all youth in the community group were enrolled in traditional school settings.

Because peer relationships researchers commonly examine victimization using a continuous approach, mean differences in peer victimization scores between the groups (chronic pain vs. community; group status by school setting) were also evaluated. Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance was significant for each of the peer victimization variables; thus, Welch’s ANOVA was used as a more rigorous test for both the main group and subgroup analyses. This technique does not allow for testing of covariates; thus age was not included in the models.1 In the subgroup analyses, statistically significant differences were evaluated using the Games-Howell post hoc test, which is recommended for use when variances differ and sample sizes are unequal (Field, 2009).

Pearson product–moment correlations were conducted for the total sample and separately for each group to determine associations among primary study variables (online supplement). Because of high correlations between the various forms of peer victimization, a composite variable was created by z-standardizing each of the five transformed victimization scores and summing them to create a total peer victimization composite for use in the mediation analyses. Mean differences between groups on this variable were also evaluated in the Welch’s ANOVA models.

A simple mediation analysis was conducted to examine the indirect effect of peer victimization on functional disability, through depression, assessed with multiple regression and bootstrapping using Hayes’s PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2012, 2013). Hayes’s (2015) index of moderated mediation was used to evaluate the moderating effect of school type on the mediating effect of depression between peer victimization and functional disability. Significance is determined by calculating 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the bias corrected method with 1000 bootstrapped samples. Tests are significant when the CI does not include zero.

Results

Participant Demographics

The final sample consisted of 73 adolescents from the community and 70 adolescents with chronic pain. Age ranged from 14 to 18 years, and the sample was predominantly female and White non-Hispanic. The chronic pain group was slightly older than the community sample. There were no other differences between groups on any demographic variable (see Table 1). Within the total sample, age was modestly associated with cybervictimization distress, r = .18, p = .028, functional disability, r = .22, p = .007 and depressive symptoms, r = .19, p = .034.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Chronic pain TS (n = 49) |

Chronic pain NTS (n = 20) |

Community (n = 73) |

Group differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% female) | 81.6% | 75% | 68.5% | χ2(2) = 2.64, p = .267 |

| Age | 16.22 (1.36)a | 16.55 (1.32)a | 15.51 (1.14)b | F(2, 139) = 8.02, p < .001 |

| Race | χ2(14) = 12.92, p = .533 | |||

| White | 81.6% | 90.0% | 73.2% | |

| Black or African American | 0% | 0% | 7% | |

| Asian American | 4.1% | 5% | 7% | |

| American Indian/AK Native | 2.0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Native HI/Other Pacific Islander | 0% | 0% | 1.4% | |

| Bi- or multi-racial | 8.2% | 5% | 2.8% | |

| Unknown/Other | 4% | 0% | 5.6% | |

| Ethnicity | χ2(8) = 2.64, p = .463 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 73.5% | 90% | 67.1% | |

| Hispanic | 14.3% | 0% | 9.6% | |

| Unknown/Decline/Missing | 12.2% | 10% | 23.3% | |

| Primary caregiver education | χ2(8) = 13.70, p = .09 | |||

| Less than high school | 4.2% | 0% | 4.2% | |

| High school graduate/GED | 12.5% | 5% | 5.6% | |

| Some college | 22.9% | 25% | 6.9% | |

| College degree | 35.4% | 25% | 36.1% | |

| Graduate/Professional degree | 25% | 45% | 47.2% | |

Note. Means with different subscripts differ significantly, p < .01. TS = traditional school; NTS = nontraditional school.

Within the chronic pain group, the majority of the sample (87%) reported daily pain of moderate intensity (m = 6.00, SD = 1.83). Most (91.4%) reported their pain lasting half the day or more, and described being moderately distressed by their pain (M = 3.55, SD = .85). Primary pain locations were predominantly musculoskeletal (60%) followed by head (32.9%) and stomach/abdominal (7.1%) pain.

Rates of Peer Victimization by Group Status

Categorical analysis.

When comparing the total chronic pain group to the community sample, no significant differences in victim status were observed (see Table 2). In the total sample, rates of victimization ranged from 9.8% (overt victimization) to 50.3% (relational victimization), with more than half (57.9%) reporting at least one type of peer victimization had occurred a few times or more in the past year; a full quarter of the total sample was categorized as experiencing peer victimization on a weekly or more frequent basis.

Table 2.

Peer Victimization Status by Group

| Peer victimization status | Chronic pain (n = 70) |

Community (n = 73) |

Total (n = 143) |

Group differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cybervictimization | ||||

| Victims | 28.6% | 29.6% | 28.7% | χ2(1) = .017, p = .895 |

| Frequent victims | 10% | 7% | 8.4% | χ 2(1) = .396, p = .529 |

| Cyberdistress | ||||

| Victims | 26.5% | 14.1% | 19.6% | χ 2(1) = 3.313, p = .067 |

| Frequent victims | 4.5% | 0% | 2.9% | χ 2(1) = 1.154, p = .355a |

| Relational victimization | ||||

| Victims | 51.4% | 49.3% | 50.3% | χ 2(1) = .064, p = .801 |

| Frequent victims | 24.3% | 18.1% | 21.3% | χ 2(1) = .911, p = .340 |

| Reputational victimization | ||||

| Victims | 32.9% | 27.4% | 30.1% | χ 2(1) = .507, p = .477 |

| Frequent victims | 10.0% | 5.5% | 7.7% | χ 2(1) = 1.028, p = .311 |

| Overt victimization | ||||

| Victims | 10.0% | 9.6% | 9.8% | χ 2(1) = .012, p = .912 |

| Frequent victims | 5.7% | 2.7% | 4.2% | χ 2(1) = .819, p = .365 |

| Any victimizationb | ||||

| Victims | 56.5% | 59.2% | 57.9% | χ 2(1) = .100, p = .752 |

| Frequent victims | 27.9% | 22.5% | 25.2% | χ 2(1) = .544, p = .461 |

Fisher’s exact test used to evaluate significance attributable to failure to meet chi square assumptions (cells had expected count less than five).

Does not include cyber-distress for ease of interpretation of anchors.

Continuous analysis.

Between group differences were observed in terms of distress associated with cybervictimization [Welch’s F(1, 99.88) = 6.52, p = .011; est ω2 .04], with youth in the chronic pain group reporting greater distress related to cyber-victimization than youth in the community group. No other differences in frequency of peer victimization emerged (all ps > .05).

Rates of Peer Victimization by Group and School Status

Categorical subgroup analysis.

There were omnibus group differences in reputational victimization status [χ2(2) = 6.818, p = .033; φ = .22] and total peer victimization status [χ2(2) = 7.922, p < .019; φ = .24]. Post hoc evaluation of adjusted standardized residuals following the procedures outlined by Beasley and Schumacker (1995) was not significant for reputational victimization (using Bonferonni corrected p values of .008; p > .03); however, post hoc tests were significant for total peer victimization status. Adolescents with chronic pain in nontraditional school settings were less likely to be classified as victims of total peer aggression compared with adolescents in the other two groups (p = .007; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Peer Victimization Status by Group and School Setting

| Peer victimization status | Chronic pain (TS) (n = 49) |

Chronic pain (NTS) (n = 20) |

Community (TS) (n = 71) |

Total (n = 140) |

Group differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cybervictimization | |||||

| Victim | 30.6% | 20% | 29.6% | 28.6% | χ2(2) = .855, p = .652 |

| Frequent victim | 14.3% | 0% | 7% | 8.6% | χ2(2) = 4.129, p = .127 |

| Cyberdistress | |||||

| Victim | 29.2% | 21.1% | 14.1% | 20.3% | χ 2(2) = 4.036, p = .133 |

| Frequent victim | 6.4% | 0% | 1.4% | 2.9% | χ 2(2) = 3.132, p = .209 |

| Relational victimization | |||||

| Victim | 59.2% | 30.0% | 49.3% | 50.0% | χ 2(2) = 4.867, p = .088 |

| Frequent victim | 28.6% | 10.5% | 18.1% | 20.7% | χ 2(2) = 3.353, p = .187 |

| Reputational victimization | |||||

| Victim | 40.8% | 10% | 27.4% | 29.6% | χ 2(2) = 6.818, p = .033 |

| Frequent victim | 12.2% | 0 | 5.5% | 7.0% | χ 2(2) = 3.814, p = .149 |

| Overt victimization | |||||

| Victim | 10.4% | 5% | 9.6% | 9.2% | χ 2(2) = .520, p = .771 |

| Frequent victim | 6.3% | 0% | 2.7% | 3.5% | χ2(2) = 1.90, p = .387 |

| Any victimizationa | |||||

| Victim | 66.7%b | 30.0%a | 59.2%b | 57.6% | χ 2(2) = 7.922, p = .019 |

| Frequent victim | 33.3% | 10.5% | 22.5% | 25.2% | χ 2(2) = 4.161, p = .125 |

Note. Percentages with different subscripts differ significantly, p < .007. TS = traditional school; NTS = nontraditional school.

Does not include cyber-distress for ease of interpretation of anchors.

Continuous subgroup analysis.

Statistically significant group differences were observed for cybervictimization, [Welch’s F(2, 64.01) = 4.65, p = .013; est ω2 = .05], cybervictimization distress [Welch ‘s F(2, 47.25), = 3.23, p = .048; est ω2 .04), relational victimization [Welch’s F(2, 53.45) = 3.73, p = .030; est ω2 = .04], reputational victimization [Welch’s F(2, 59.9) = 4.66, p = .013; est ω2 .05), and overt victimization [Welch’s F(2, 72.09) = 4.02, p = .022; est ω2 .04). Games-Howell post hoc tests revealed youth with chronic pain enrolled in traditional school settings reported more frequent cybervictimization (p = .014), relational victimization (p = .023), reputational victimization (p = .009), and overt victimization (p = .034) experiences compared to youth with chronic pain not enrolled in traditional schools. In addition, youth with chronic pain attending traditional school reported more distress associated with cybervictimization compared to healthy youth (p = .034); there were no differences between the pain groups on this variable. No additional differences were observed between healthy youth or either chronic pain group.

Welch’s ANOVA was also used to evaluate group differences on total victimization exposure, using the z-standardized composite variable comprised of the traditional and cybervictimization scores. This test was significant [Welch’s F(2, 71.94) = 6.22, p = .003; est ω2 .07]. Games-Howell post hoc tests revealed that youth with chronic pain attending traditional school settings reported significantly more victimization experiences compared to youth with chronic pain not enrolled in traditional school settings (p = .007). Healthy youth also reported significantly more victimization experiences than youth with chronic pain not enrolled (p = .028). No significant difference was observed between healthy youth and youth with chronic pain attending traditional schools.

Mediation Analyses

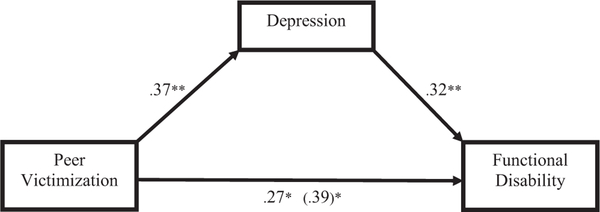

Within the chronic pain group, significant direct and indirect effects were observed in the simple mediation analysis (see Figure 1). Peer victimization significantly predicted depression, β .37, t(68) = 2.82, p = .006, depression significantly predicted functional disability, β .32, t(68) = 2.74, p = .008, and peer victimization significantly predicted functional disability,β = .39, t(68) = 3.02, p = .003. The bootstrapped unstandardized indirect effect was .12, BCa 95% CI [.01, .30], suggesting a significant mediating effect of depression on the relationship between victimization and disability. After accounting for this indirect effect, there was a remaining direct effect of peer victimization on functional disability, β .27, t(68) 2.11, p = .038 (CI [.01, .53]).

Figure 1.

Mediation. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between peer victimization and functional disability, as mediated by depression. The standardized total effect between victimization and disability, controlling for depression, is in parentheses.**p < .01. *p < .05.

In the preliminary analyses, school type (traditional or nontraditional) was significantly related to overall peer victimization, r = .27, p = .025, showing that adolescents with chronic pain in traditional school reported higher levels of victimization than their peers in nontraditional school. Within this chronic pain subgroup, the peer victimization composite was significantly associated with depression, r = .40, p = .004 and functional disability, r = .47, p = .001. When considering only individuals with chronic pain in nontraditional schools, the relationship between peer victimization and depression, r = .08, p = .755 and depression and functional disability, r = .41, p = .071 were nonsignificant. Consequently, an exploratory moderated mediation analysis was conducted with PROCESS to determine whether school setting moderated the strength of the mediated relationship between peer victimization and functional disability through depression (online supplement). The index of moderated mediation suggested a nonsignificant conditional effect of school type on the mediating effect of depression on the relationship between victimization and functional disability (index = .09; 95% CI [ 0.24, 0.69]. Thus, there was no evidence of moderated mediation.

Discussion

Peer victimization is a major public health concern and has been associated with a wide range of negative physical and mental health outcomes in otherwise healthy youth (e.g., Herge et al., 2016; McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). Biopsychosocial models of pain emphasize the important role of social factors as contributors to physical pain and its correlates; however, systematic research investigating peer relationship problems in youth with chronic pain conditions is limited (Forgeron et al., 2011). As peers are prominent figures in the adolescent social network and make important contributions to normative, healthy development (Viner et al., 2012), experiencing peer relationship problems during this developmental period may place vulnerable youth on a negative health trajectory. Ideally, identification of the nature and extent of peer relationship problems, including peer victimization experiences, can inform more effective and developmentally appropriate pediatric pain prevention and intervention efforts. Thus, the major aims of this study were to establish rates of self-reported peer victimization experienced by adolescents with chronic pain compared to their otherwise healthy peers, and to evaluate the relationships between peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and pain-related functional disability. This study is the first to comprehensively assess perceived peer victimization in a clinical sample of adolescents with chronic pain compared to a community peer group.

Findings reveal that peer victimization is commonly experienced by youth with chronic pain, particularly those enrolled in traditional school settings, though at rates similar to their otherwise healthy peers. Overall, indirect forms of victimization, including relational, reputational, and cyber-victimization were more common than direct, physical forms of victimization. Relational victimization (i.e., social exclusion) was most commonly experienced, with fully half the sample reporting experiencing this form of victimization a few times or more in the past year, and a fifth reporting relational victimization experiences on a weekly or more frequent basis. Overall, a quarter of the sample reported experiencing some form of peer victimization at least weekly in the past year. Victimization rates reported in the present study are commensurate with rates that have been reported in the extant literature for this age group (Modecki et al., 2014; Selkie et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2009).

When considering peer victimization from a continuous perspective, overall mean levels of victimization were similar for youth with chronic pain compared to the community sample; however, a significant difference did emerge with respect to distress reported as a function of peer-based cyber aggression. Of note, two measures of cyber-victimization were used in this study. On one measure adolescents report how frequently they were the target of peer-based acts of aggression online, whereas the other measure assesses how frequently the adolescents were emotionally bothered by their online peer victimization experiences. In this sample, there were no differences in frequency of perceived cybervictimization; however, youth with chronic pain were more likely to report feeling humiliated, hurt, threatened, or harassed by their online peer victimization experiences compared with youth without chronic pain. Thus, despite reporting equivalent exposure to cyber-victimization, youth with chronic pain were more emotionally bothered by the victimization when it did occur. These findings are consistent with prior research that has revealed social information processing differences among youth with chronic pain, namely that youth with chronic pain may have a heightened emotional sensitivity to negative social interactions compared to their healthy peers (Forgeron et al., 2011). At present, there is no parallel measure that assesses emotional distress as a function of the more traditional forms of victimization; however, this is an important avenue for future research. Although there are well-established links between merely being the perceived target of peer aggression and negative outcomes (La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Landoll et al., 2013; Prinstein et al., 2001), it is possible that actually being distressed by the aggressive acts would be a more clinically relevant indicator, and may vary as a function of chronic pain status. To the extent that this distress is driven by social information processing differences—in interpretation of intent or biased expectations regarding others’ behaviors—targeted social– cognitive interventions can be utilized.

An exploratory aim of the study was to determine whether type of school setting is associated with peer victimization experiences for youth with chronic pain. This variable has not been addressed in prior research. Despite being underpowered to detect significant differences in the subgroup analyses, statistically significant differences were observed with respect to reputational victimization status and overall peer victimization status. Relative to their counterparts enrolled in traditional school contexts, youth with chronic pain not enrolled in school or attending home or online schools were less likely to be classified as victims of peer victimization overall, and specifically reputational victimization. When considering peer victimization as a continuous variable, youth with chronic pain in nontraditional school reported fewer instances of all forms of peer victimization compared to their peers with chronic pain enrolled in traditional school. These lower rates of peer victimization may be a function of limited contact with peers. Although not attending traditional schools may offer some protection from acts of peer aggression in the short-term, limited involvement with peers in normative contexts could have devastating consequences for future social functioning and quality of life. It is also possible that youth not enrolled in traditional schools may have a more distal history of peer victimization than would have been captured by the reporting time frame of the current study; it may be valuable for future researchers to evaluate lifetime history of peer victimization. The findings, while preliminary, underscore the importance of considering school setting when evaluating peer victimization clinically and in research contexts.

The final aim was to explore the relationship between peer victimization, depression, and pain-related functional disability within the group of adolescents with chronic pain. Peer victimization was associated with depressive symptoms and functional disability, and results of simple mediation showed that peer victimization had a significant indirect effect on functional disability, with depression as a mediator. Though depressive symptoms partially accounted for the relationship between victimization and functional disability, peer victimization also maintained its direct effect on functional disability. School type did not moderate the indirect pathway. These correlational findings highlight peer victimization as a possible risk variable that, in conjunction with depression, could be targeted in interventions designed to improve functional disability in adolescents with chronic pain.

It is important to consider these results in the context of some limitations. First, this study is limited by its relatively small sample size. This study was originally powered to detect medium effects between two groups on continuous variables; consequently, the ability to detect statistically significant differences in the subgroup analyses was limited, particularly when variables were dichotomized. Nevertheless, there does appear to be value in presenting these subgroup analyses as there may be meaningful differences in peer victimization status as a function of school setting for youth with chronic pain. Future research examining peer relationship factors within this population should carefully consider school context and other indicators of adolescents’ exposure to and engagement with same-age peers, and should be adequately powered to control for such differences.

Second, this study employed a cross-sectional design, meaning that the causal relationships between the variables of interest cannot be determined. Though the mediation analysis proposes that peer victimization leads to depression and functional disability, the study design precludes making such causal inferences and alternative models and other temporal ordering of these variables cannot be ruled out. Future studies are needed using longitudinal designs to clarify the impact of peer victimization on depression and pain-related outcomes.

Finally, measurement issues have been described as the “Achilles’ heel” of peer victimization research (Cornell, Sheras, & Cole, 2006; Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Self-report of peer victimization status is commonly used in adolescent samples and may be the best option for youth with chronic pain, as more rigorous methods like peer nominations are not practicable, especially when youth are not enrolled or regularly attending school. Though there is good evidence for the validity and reliability of the measures used in this study, measurement issues remain a challenge for peer victimization research (Berne et al., 2013; Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Though self-report of peer victimization may limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this study, it remains an important assessment tool in a clinical context, as subjective experience is essential for informing effective treatment. Future research could use controlled social exclusion laboratory paradigms as a novel experimental strategy for examining the impact of peer victimization on youth with chronic pain.

The results of this study suggest that peer victimization may be an important domain to consider in evaluation and treatment of youth with chronic pain. Those attending traditional schools may be at the greatest risk for peer victimization, and there is preliminary evidence that they may be more bothered by some of these experiences than their otherwise healthy peers. Given the observed associations between peer victimization, depression, and functional disability in the present study, future research should continue to evaluate peer victimization as a risk factor for adjustment difficulties within adolescents with chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Traditional one-way ANCOVAs/ANOVAs with and without age included as a covariate were also conducted and essentially replicated all results reported, with the sole exception that subgroup differences for overt victimization were no longer significant when age was included in the model. All other significant findings remained.

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hea0000569.supp

Contributor Information

Jessica L. Fales, Washington State University and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington

Sean Rice, Washington State University.

Rachel V. Aaron, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, and University of Washington

Tonya M. Palermo, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, and University of Washington

References

- Beasley TM, & Schumacker RE (1995). Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. Journal of Experimental Education, 64, 79–93. 10.1080/00220973.1995.9943797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berne S, Frisén A, Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H, Naruskov K, Luik P, … Zukauskiene R (2013). Cyberbullying assessment instruments: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 320–334. 10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Taliaferro LA, & McMorris BJ (2013). Suicidal thinking and behavior among youth involved in verbal and social bullying: Risk and protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, S4–S12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, & Francis SE (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM–IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 835–855. 10.1016/S00057967(99)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell DG, Sheras PL, & Cole JC (2006). Assessment of bullying In Jimerson S. & Furlong M. (Eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety: From research to practice (pp. 191–210). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Grotpeter JK (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722. 10.2307/1131945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Prinstein MJ (2004). Applying depressiondistortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 325–335. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick BD, & Pillai Riddell R. (2010). Cognitive and school functioning in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A critical review. Pain Research & Management, 15, 238–244. 10.1155/2010/354812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, & Lynam D. (2006). Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth In Damon W. & Eisenberg N. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 719–788). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Fales JL, & Forgeron P. (2014). The importance of friendships in youth with chronic pain: The next critical wave of research. Pediatric Pain Letter, 16, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes M, Pijpers FI, Fredriks AM, Vogels T, & Verloove-Vanhorick SP (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117, 1568–1574. 10.1542/peds.2005-0187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. (2008). Childhood victimization: Violence, crime, and abuse in the lives of young people. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195342857.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgeron PA, King S, Stinson JN, McGrath PJ, MacDonald AJ, & Chambers CT (2010). Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Research & Management, 15, 27–41. 10.1155/2010/820407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgeron PA, McGrath P, Stevens B, Evans J, Dick B, Finley GA, & Carlson T. (2011). Social information processing in adolescents with chronic pain: My friends don’t really understand me. Pain, 152, 2773–2780. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gini G, & Pozzoli T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132, 720–729. 10.1542/peds.2013-0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco LA, Freeman KE, & Dufton L. (2007). Overt and relational victimization among children with frequent abdominal pain: Links to social skills, academic functioning, and health service use. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 319–329. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadatadriven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42, 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White Paper]. Retrieved from http://afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herge WM, La Greca AM, & Chan SF (2016). Adolescent peer victimization and physical health problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 15–27. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, & Chou C. (2010). An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1581–1590. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huguet A, & Miró J. (2008). The severity of chronic pediatric pain: An epidemiological study. The Journal of Pain, 9, 226–236. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, & Swearer SM (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70, 293–299. 10.1037/a0038928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Powers SW, Vaught MH, & Hershey AD (2001). Depression and functional disability in chronic pediatric pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 17, 341–349. 10.1097/00002508-200112000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, & MacDonald AJ (2011). The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: A systematic review. Pain, 152, 2729–2738. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kochel KP, Ladd GW, & Rudolph KD (2012). Longitudinal associations among youth depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and low peer acceptance: An interpersonal process perspective. Child Development, 83, 637–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, & Limber SP (2013). Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, S13–S20. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Harrison HM (2005). Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 49–61. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoll RR, La Greca AM, & Lai BS (2013). Aversive peer experiences on social networking sites: Development of the Social Networking-Peer Experiences Questionnaire (SN-PEQ). Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 695–705. 10.1111/jora.12022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DE, Simons LE, Stein MJ, & Chastain L. (2008). School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. The Journal of Pain, 9, 407–416. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall P, & Vaillancourt T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70, 300–310. 10.1037/a0039174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, & Runions KC (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 602–611. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM (2000). Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 21, 58–69. 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM, Lewandowski AS, Long AC, & Burant CJ (2008). Validation of a self-report questionnaire version of the Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI): The CALI-21. Pain, 139, 644–652. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, & Vernberg EM (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 479–491. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, & Telch MJ (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 244–252. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stöven H, Schwarzenberger J, & Schmucker P. (2005). Pain among children and adolescents: Restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics, 115, e152–e162. 10.1542/peds.2004-0682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkie EM, Fales JL, & Moreno MA (2016). Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high school–aged adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 125–133. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LE, Logan DE, Chastain L, & Stein M. (2010). The relation of social functioning to school impairment among adolescents with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 26, 16–22. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b511c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg ME, & Olweus D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239–268. 10.1002/ab.10047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Needham Height, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Tegethoff M, Belardi A, Stalujanis E, & Meinlschmidt G. (2015). Comorbidity of mental disorders and chronic pain: Chronology of onset in adolescents of a national representative cohort. The Journal of Pain, 16, 1054–1064. 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Hamby SL, Shattuck A, & Ormrod RK (2011). Specifying type and location of peer victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1052–1067. 10.1007/s10964-011-9639-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK, & Card NA (2013). Moving beyond tradition and convenience: Suggestions for useful methods of cyberbullying research In Bauman S, Cross D, & Walker J. (Eds.), Principles of cyberbullying research: Definition, measures, and methodology (pp. 125–140). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, Brittain HL, McDougall P, & Duku E. (2013). Longitudinal links between childhood peer victimization, internalizing and externalizing problems, and academic functioning: Developmental cascades. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 1203–1215. 10.1007/s10802-013-9781-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, & Currie C. (2012). Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 379, 1641–1652. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer CL (2011). Interpreting the high prevalence of pediatric chronic pain revealed in community surveys. Pain, 152, 2683–2684. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer CL, Spagrud LJ, McCormick JC, Choo E, Neville K, & Connelly MA (2009). Three new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children’s self-reports of pain intensity. Pain, 143, 223–227. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, & Nansel TR (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 368–375. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EL, Boye AE, & Nelson DA (2006). Relational aggression: Understanding, identifying, and responding in schools. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 297–312. 10.1002/pits.20148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.