Abstract

Background:

Peroxidation of PUFAs by a variety of endogenous and xenobiotic electrophiles is a recognized pathophysiological process that can lead to adverse health effects. Although secondary products generated from peroxidized PUFAs have been relatively well studied, the role of primary lipid hydroperoxides in mediating early intracellular oxidative events is not well understood.

Methods:

Live cell imaging was used to monitor changes in glutathione (GSH) oxidation in HAEC expressing the fluorogenic sensor roGFP during exposure to 9-hydroperoxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HpODE), a biologically important long chain lipid hydroperoxide, and its secondary product 9-hydroxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE). The role of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was examined by direct measurement and through catalase interventions. shRNA-mediated knockdown of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4) was utilized to determine its involvement in the relay through which 9-HpODE initiates the oxidation of GSH.

Results:

Exposure to 9-HpODE caused a dose-dependent increase in GSH oxidation in HAEC that was independent of intracellular or extracellular H2O2 production and was exacerbated by NADPH depletion. GPx4 was involved in the initiation of GSH oxidation in HAEC by 9-HpODE, but not that induced by exposure to H2O2 or the low molecular weight alkyl tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBH).

Conclusions:

Long chain lipid hydroperoxides can directly alter cytosolic EGSH independent of secondary lipid oxidation products or H2O2 production. NADPH has a protective role against 9-HpODE induced EGSH changes. GPx4 is involved specifically in the reduction of long-chain lipid hydroperoxides, leading to GSH oxidation.

Significance:

These results reveal a previously unrecognized consequence of lipid peroxidation, which may provide insight into disease states involving lipid peroxidation in their pathogenesis.

Keywords: lipid peroxidation, glutathione, hydroperoxide, glutathione peroxidase 4

Introduction

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have essential roles in cellular homeostasis and the inflammatory response. Peroxidation of PUFAs has the potential to both disrupt membrane structure and generate bioactive lipid oxidation products that have adverse downstream effects (1–4). For instance, lipid peroxidation is believed to contribute to normal aging (5, 6) and the effects of exposure to certain xenobiotics (7) and environmental contaminants (8). It is also associated with various neurological disorders (9, 10), and the oxidation of PUFAs on low density lipoproteins (LDL) has been linked to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (11–13).

The chemistry of lipid peroxidation has been relatively well characterized (14, 15). The peroxidation of an unsaturated carbon-carbon bond can occur enzymatically, as in the reactions catalyzed by cyclooxygenase (COX) or lipoxygenase (LOX) (16, 17), or be initiated by a free radical, such as hydroxyl or alkoxyl radicals, or by singlet oxygen or ozone (15). The stereo specificity of the resulting hydroperoxides can help identify the process that generated them. For example, different isomers of the hydroperoxide hydroperoxy-octadecadienoic acid (HpODE) are formed depending on whether linoleic acid is subjected to enzymatic, free radical, or non-radical attack (14). Furthermore, the products formed from the peroxidation of a carbon-carbon double bond are dependent on the chain length and degree of unsaturation of the parent PUFA.

Once formed, lipid hydroperoxides can undergo transition metal-mediated decomposition (18, 19), or can be reduced enzymatically (3). Through these mechanisms lipid hydroperoxides, the primary products of peroxidation, can form secondary products such as alcohols, aldehydes, endoperoxides, and cyclopentenones (15). A number of secondary lipid oxidation products, such as 4-hydroxy-nonenal (HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA), have been well studied and linked to a variety of downstream effects including alteration of signaling pathways (4), protein and DNA adduction (20), and both the promotion and resolution of inflammation (2, 21). Secondary products of lipid peroxidation have also been utilized as biomarkers of oxidative stress in vivo, including the hydroxy derivatives of linoleic acid (HODEs) and the F2-isoprostanes (IsoPs) formed from arachidonic acid (22). While the mechanisms of lipid peroxidation and the bioactivity of these secondary products have been relatively well characterized, the biological effects of the primary products of peroxidation, the hydroperoxides, remain less understood. This is in part due to their relative instability in aqueous environments and short half-life in biological systems. Live-cell confocal microscopy using fluorogenic sensors is well suited for the observation of early oxidative events induced by short-lived intermediates.

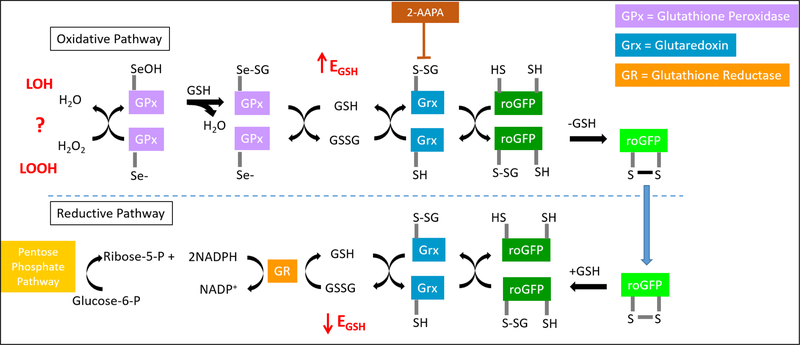

Glutathione (GSH) is the most abundant intracellular antioxidant, with millimolar concentrations present in the cytosol of most cell types. The ratio of oxidized (GSSG) to reduced glutathione, which defines the glutathione redox potential (EGSH) in the Nernst equation, is an important indicator of overall cellular oxidative state (23). Under homeostatic conditions, the EGSH reflects a ratio of GSH:GSSG of 100:1. roGFP is a genetically encoded fluorogenic sensor that has been used in a variety of cell types for real-time assessments of the EGSH (24). roGFP has been shown to equilibrate with EGSH through a redox relay that is initiated by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and involves the participation of the enzymes GPx, glutaredoxin (Grx), and glutathione reductase (GR) (Figure 1). Whether lipid hydroperoxides can alter EGSH through this relay is not currently known.

Figure 1. The redox relay by which roGFP equilibrates with the glutathione redox potential (EGSH).

Glutathione peroxidases (GPx) reduce peroxides while oxidizing glutathione (GSH) to form glutathione disulfide (GSSG), thus increasing EGSH. The oxidized and reduced forms of the fluorogenic sensor, roGFPox/roGFPred, equilibrate with the GSH/GSSG redox couple via linkage with glutaredoxin (Grx), which can be inhibited by the small molecule 2-AAPA. In the reductive pathway, Grx catalyzes the reduction of roGFPox through deglutathionylation as normal levels of GSH are reestablished by glutathione reductase (GR) at the expense of NADPH. NADPH is formed during the metabolism of glucose in the pentose phosphate pathway.

Linoleic acid (octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid, 18:2) is a prevalent fatty acid esterified to membrane phospholipids, and is the most abundant PUFA attached to human LDL (25). Additionally, linoleic acid is present in the surfactant lining the airway epithelium (26), where it is a target of lipid peroxidation by oxidizing air pollutants such as ozone (27). 9-hydroperoxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HpODE) is a product of linoleic acid peroxidation that can be generated enzymatically or via radical or non-radical mediated oxidation. Increased levels of 9-hydroxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE), the reduced form of 9-HpODE, have been reported in the blood of patients with atherosclerotic plaques as well as in older, otherwise healthy individuals (25). We hypothesized that exposure of human airway epithelial cells (HAEC) to 9-HpODE would result in an alteration of intracellular EGSH. In the present study, we characterized the effect of exposure to 9-HpODE on HAEC expressing roGFP. We show that 9-HpODE induces a dose-dependent increase in GSH oxidation that is independent of intracellular H2O2 production and is mediated by glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4).

Methods

Materials and Reagents

All media and supplements for tissue culture were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA). Wilco Wells glass-bottomed culture dishes for microscope analysis were obtained from Ted Pella Inc. (Redding, CA, USA). Laboratory reagents and chemicals including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBH), dithiothreitol (DTT), 2-acetylamino-3-[4-(2-acetylamino-2-carboxyethylsulfanylthiocarbonylamino)phenylthiocarbamoylsulfanyl]propionic acid (2-AAPA), hexadimethrine bromide (polybrene), D-(+)-glucose, catalase from bovine liver, and sodium selenite were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Basic laboratory supplies were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Raleigh, NC, USA). 9-hydroperoxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HpODE) and 9-hydroxy-10E,12Z -octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Pittsfield Charter Township, MI, USA). The antibodies for glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4), catalase, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA), and Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), respectively.

Cell Culture

SV40 large T antigen-transformed human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B, subclone s6) (28) were cultured in serum-free keratinocyte growth medium (KGM). BEAS-2B cells have been used extensively as a model of airway epithelium for in vitro testing of inhaled toxicants (29–32). BEAS-2B cell cultures, either wild type or transduced to stably express a fluorescent reporter, were renewed from stocks frozen in liquid nitrogen every 1–2 months for the duration of the study. Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37° C in 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). For live-cell exposures, cells were plated in 35 mm Wilco Well glass-bottomed dishes with a 12 mm #1.5 glass aperture.

Genetically Encoded Constructs

The plasmid for roGFP2 was the generous gift of S.J. Remington (University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA). The plasmid for the H2O2 sensor, HyPer, was purchased from Evrogen (Axxora, Farmingdale, NY, USA). An adenoviral vector encoding the over-expression of catalase (“AdCAT”) was purchased from the University of Iowa Viral Vector Core (Iowa City, IA, USA).

shRNA Design

shRNA hairpin oligonucleotides shown below were designed by selecting an 18-nt site from the human GPx4 complete mRNA (NCBI Accession: BC046163.1) optimized for siRNA targeting of GPx4 mRNA (S080) or a random 18-nt sequence (scramble) with no predicted homology to human genomic or transcript sequences.:

S080: 5’- CCGAAGTAAACTACACTC-3’

Scramble: 5’-ACTCTCGCCCAAGCGAGA-3’

Single stranded synthetic 97-nt oligonucleotides (Invitrogen Corp., Valcencia, CA) incorporating sense/antisense sequences in a stem-loop motif were PCR amplified using the primers forward: 5’-AGTCACTCGAGTGCTGTTGACAGTGAG-3’ and reverse: 5’-AAGTCAGGATCCTCCGAGGCAGTAGG-3.’ The resulting PCR products were subcloned into a modified lentiviral transfer vector, pRIPZ (Dharmacon, Birmingham, AL) between XhoI and BamHI restriction sites. The resulting shRNA expression constructs were verified by fluorescent DNA capillary sequencing. This cloning strategy nests the shRNA fragments between 5’ and 3’ miRNA30 adaptors within the 3’ untranslated region of a polycistronic red fluorescent protein reporter gene under the control of a CMV promoter.

Lentiviral Vector Production and Titering

HEK293T cells were co-transfected in 10 cm dishes with purified transfer vector plasmids and lentiviral packing mix (Dharmacon; Birmingham, AL) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 16 hr post-transfection, cell culture medium was replaced with fresh media and cells were incubated for an additional 48 hr at 37°C. Medium was then harvested and detached cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 5,000 x g. The resulting supernatants from the individual transfections were concentrated once by low-speed centrifugation through an Amicon Ultra 100kD centrifuge filter unit (Millipore; Billerica, MA), and the retentates were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. To determine viral titers, 2 × 104 HEK293T cells were transduced with 50 μL of lentiviral stock dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:781,250. Viral titers (expressed as transducing units per mL viral stock) were determined 96 hr post-transduction by counting fluorescent cell colonies by fluorescent microscopy and multiplying the colony count by the dilution and volume factors.

Viral Transduction

Stable expression of genetically encoded fluorescent reporters was attained via lentiviral transduction of BEAS-2B cells. Lentivirus encoding roGFP2 or HyPer was incubated for 4 hr with wild type BEAS-2B cells in keratinocyte basal media (KBM) using a multiplicity of infection of 2–5. The transduction was performed in a single well of a 6-well dish when cells were 40 – 60 % confluent. Hexadimethrine bromide (polybrene) was added to the well at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL. Dishes were gently rocked every 30–45 min to redistribute viral particles. After 4 hr, 1 mL of KGM was added to the well for a second incubation of 4 hr. The media was then replaced with fresh KGM, and the cells grown until confluence. Transduced cells were then expanded to a T75 culture flask and passaged for use in experiments. Stocks of BEAS-2B cells expressing each reporter (roGFP-BEAS and HyPer-BEAS) were stored in liquid nitrogen. Cells were used in experiments for approximately 20 passages, after which a new stock of lower passage was thawed.

Stable expression of the GPx4 knockdown followed the same protocol with the following exceptions: transduction was performed on roGFP-BEAS, no polybrene was added to the well, and cells were only utilized in experiments for a maximum of 2 weeks following transduction. Transient overexpression of catalase was achieved using an adenoviral vector. All AdCat experiments were conducted under glucose sufficient conditions (33). The transduction protocol was the same as those for roGFP2 and HyPer with the following exceptions; a multiplicity of infection of 200 was used, transduction was performed when cells were approximately 80% confluent, and transduction occurred in glass bottomed dishes for immediate imaging analysis the following day.

Exposure Conditions

Transduced BEAS-2B cells were cultured in glass bottomed dishes for imaging analysis. Cells were cultured in KGM until approximately 75% confluent. Prior to exposures, cells were equilibrated in 0.5 mL minimal salt solution, Locke buffer (34), supplemented with 10 mM D-(+)-glucose for 15 min. For glucose deprivation experiments, cells were equilibrated in Locke buffer without glucose for 2 hr prior to analysis. Dishes were then placed in a custom-built stage-top exposure system maintained at 37°C with 1.5 L/min 5% CO2/balance air at a relative humidity of ≥ 95%. In some experiments cells were pretreated with 100 μM 2-AAPA, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in KBM, for 2 hr prior to equilibration in Locke buffer. Pre-treatment of cells with 1 μM sodium selenite, dissolved in water and diluted in KBM, occurred for 36 hr prior to exposures to induce over-expression of GPx. Exogenous catalase was added in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 100 units/mL (stock was provided at 2,000 – 5,000 units/mg protein). Heat inactivated catalase treatments were conducted for 10 min at 95°C.

Each experiment consisted of three component intervals. They included a) an untreated baseline period of 5 min b) an exposure period of 15 – 25 min to a lipid hydroperoxide, hydroxide, or vehicle control, and c) a 10 min control period during which cells were oxidized by 0.1 – 1.0 mM H2O2 for 5 min and then reduced by 5 mM DTT for an additional 5 min (Figure S1). All experiments involving treatments with paired controls were analyzed within one hour of each other.

Preparation of Lipid Hydroperoxides

Lipid hydroperoxides or hydroxides were supplied in ethanol in gas-tight vials with a septum and the headspace purged with nitrogen. Immediately prior to each experiment the appropriate volume of ethanol was drawn into a gas-tight glass syringe. The solution was transferred to a 300 μL glass conical vial and dried under a steady stream of nitrogen gas. Dried stocks were re-suspended in the appropriate volume of PBS, vortexed vigorously for 2 min, and used immediately. Concentrations of lipid hydroperoxides in all working solutions were below the aqueous solubility of 1 mg/mL for both 9-HpODE and 9-HODE.

Imaging Analysis

All live-cell imaging experiments were conducted using a Nikon Eclipse C1si spectral confocal imaging system equipped with an Eclipse Ti microscope, Perfect Focus System, and 404 nm, 488 nm, and 561 nm primary laser lines (Nikon Instruments Corporation, Melville, NY, USA). Images were acquired using a 1.4 NA 60X violet-corrected, oil-immersed objective lens. For experiments involving roGFP and HyPer, green fluorescence was observed through sequential excitations with 488 nm and 404 nm light, and emitted light was collected for each using a 525/30 nm band-pass filter (Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). For experiments with the GPx4 KD, red fluorescence was observed using excitation at 561 nm light and emitted light collected with a 605/75 nm band-pass filter. Acquisition parameters of laser power and pixel dwell time were kept constant between experiments, and the gain was optimized for each experiment. Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn around entire, individual cells in the field view. Each independent experiment monitored the same 5–10 ROI for the duration of the experiment. Results were calculated as the ratios of the emissions excited by the 488 and 404 nm lasers for each sensor. Ratios were calculated individually for each cell observed and normalized to individual cell baselines. In some experiments, normalized ratios were then expressed as a percentage of the maximum response achieved by that cell during oxidation with 1 mM H2O2 at the end of the experiment.

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was assessed by measuring the activity of released lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using the CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Catalog #G1780, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The assay was performed per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, roGFP-BEAS were exposed in a 96 well plate to various doses of 9-HpODE, 9-HODE, or vehicle control under conditions mimicking those of imaging exposures. Media from each well was incubated with LDH reagent for 30 min and absorbance was read at 490 nm using a CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Percent cytotoxicity was calculated for each condition as compared to lysed controls.

Statistical Analysis

All imaging data were quantified using NIS-Elements AR software (Nikon). All statistical analysis and graphs were prepared using PRISM (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

The lipid hydroperoxide 9-HpODE induces oxidation of intracellular GSH

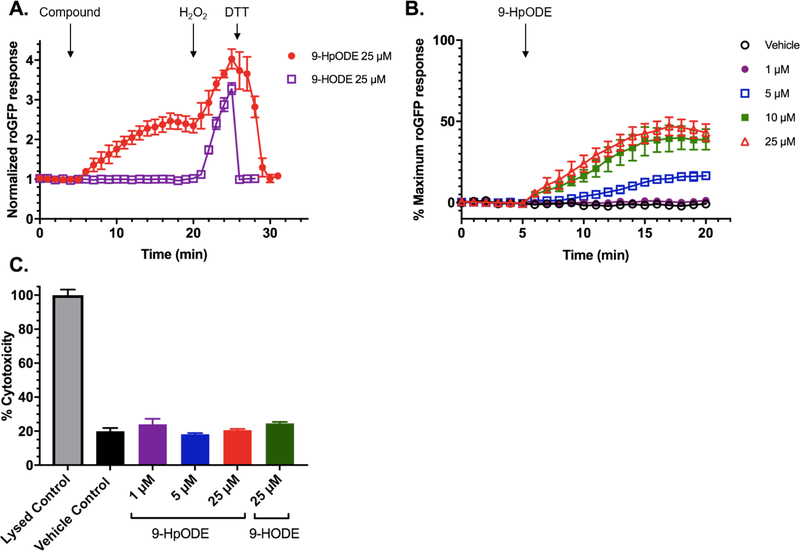

In order to determine whether exposure to the long chain lipid hydroperoxide 9-HpODE induces changes in the indicator of intracellular redox status EGSH, BEAS-2B cells expressing the EGSH sensor roGFP (“roGFP-BEAS”) were exposed to 9-HpODE. As shown in Figure 2B, there was a rapid and sustained increase in GSH oxidation in response to the addition of 5–25 μM 9-HpODE, with cells remaining responsive to further oxidation by 1 mM H2O2 and subsequent reduction with 5 mM DTT. In contrast, exposure to the same concentration of 9-HODE, the reduced product of 9-HpODE, did not result in GSH oxidation, as reported by roGFP, over the same period (Figure 2A). The doses of 9-HpODE and 9-HODE used in these experiments were not cytotoxic to cells within the time interval tested (Figure 2C). Exposure to 25 μM isomeric 13-HpODE and 13-HODE, also formed from the peroxidation and subsequent reduction of linoleic acid, resulted in roGFP responses of similar magnitudes (data not shown).

Figure 2. The lipid hydroperoxide 9-HpODE, but not its hydroxy derivative 9-HODE, induces a rapid and dose-dependent change in GSH oxidation.

A) Comparison of the response of roGFP-BEAS to exogenous addition of 25 μM 9-HpODE or the corresponding hydroxide, 9-HODE. Compounds were dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) immediately prior to the experiment. Addition of each compound occurred after the collection of a 5 min baseline period, followed by addition of 1 mM H2O2 (maximal sensor response) and 5 mM DTT at 20 and 25 min, respectively. Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to the baseline. B) Response of roGFP-BEAS to exogenous addition of 0–25 μM concentrations of 9-HpODE. Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to the baseline and maximal sensor responses. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, where each n represents an individual dish in which 5–10 distinct cells were monitored. C) Cytotoxicity of doses of 9-HpODE and 9-HODE used in this study on BEAS-2B cells. Cytotoxicity was assessed using release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from cells exposed to 9-HpODE, 9-HODE, or vehicle control for 25 min. LDH activity was measured using a commercial colorimetric kit, performed per manufacturer’s directions. Values are presented as mean ± SEM, n=3.

The oxidation of GSH induced by 9-HpODE is not mediated by H2O2

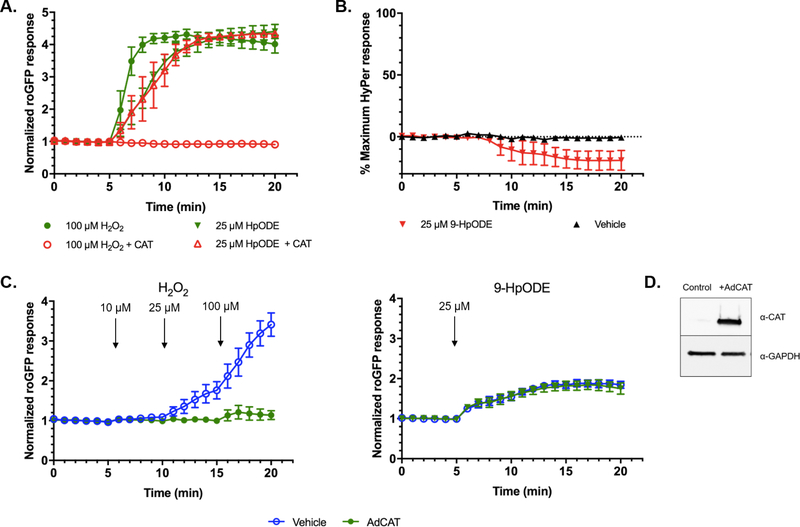

H2O2 produced by secondary reactions of lipid hydroperoxides in aqueous solutions or in the cytosol have been proposed to contribute to their biological effects (35–37). We therefore examined whether the oxidative effect of 9-HpODE on GSH is mediated by H2O2. We first exposed roGFP-BEAS to 9-HpODE in the presence of a concentration of extracellular catalase sufficient to completely ablate the roGFP response to 100 μM H2O2 (Figure 3A). We observed no change in the roGFP response of cells exposed to 9-HpODE in the presence of the same concentration of extracellular catalase (Figure 3A). As expected, heat inactivated catalase failed to ablate the roGFP response to either H2O2 or 9-HpODE (data not shown).

Figure 3. The GSH oxidation induced by 9-HpODE is independent of H2O2.

Exogenous and intracellular catalase interventions were utilized to determine the role of H2O2 in 9-HpODE-induced GSH oxidation. A) Glucose-deprived roGFP-BEAS were treated with of 25 μM H2O2 or 9-HpODE in the presence of 100 U/mL of extracellular catalase. B) BEAS-2B cells expressing the fluorogenic sensor of H2O2, HyPer, were exposed to 25 μM 9-HpODE. C) Catalase was overexpressed in roGFP-BEAS using an adenoviral vector (“AdCAT”). The roGFP response in AdCAT transduced, glucose sufficient roGFP-BEAS following the sequential addition of 10, 25, and 100 μM H2O2 at 5, 10, 15 min respectively (left panel). AdCAT transduced roGFP-BEAS were stimulated with 25 μM 9-HpODE at 5 min (right panel). Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to the baseline in panels A and C, and further normalized to maximal sensor response in panel B. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, where each n represents an individual dish in which 5–10 distinct cells were monitored. D) Catalase overexpression in transduced cells detected by western blotting.

We then addressed the possibility that 9-HpODE activates the redox relay that leads to GSH oxidation (increased EGSH), sensed by roGFP, through the production of intracellular H2O2. An adenoviral vector (“AdCAT”) was used to induce catalase over-expression in roGFP-BEAS. Preliminary experiments established that an MOI of 200 was optimal for expression of catalase and blocked GSH oxidation reported by roGFP responses induced by up to 1 mM H2O2 (Figure 3C, S2) without inducing changes in cell morphology (data not shown). In contrast, GSH oxidation induced by 25 μM 9-HpODE in cells overexpressing catalase was virtually identical to that of control roGFP-BEAS over the entire period tested (Figure 3C).

Additionally, we measured intracellular levels of H2O2 in BEAS-2B cells expressing the genetically encoded fluorogenic sensor of H2O2, HyPer (HyPer-BEAS). As shown in Figure 3B, no increase in intracellular concentrations of cytosolic H2O2 was observed in HyPer-BEAS following exposure to 25 μM 9-HpODE. Taken together, these findings showed that H2O2 is not involved in the oxidation of GSH induced by 9-HpODE.

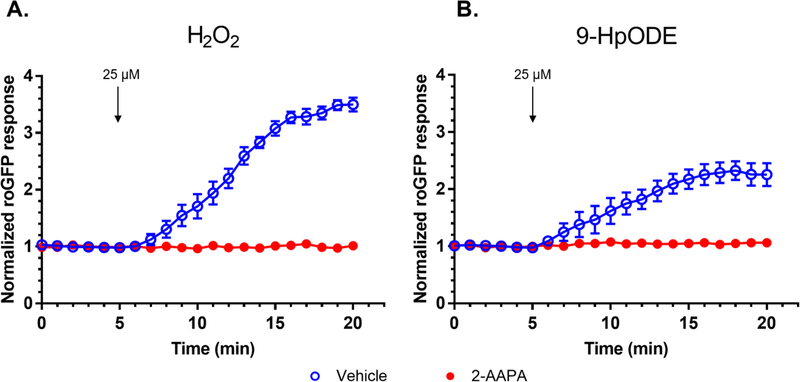

We next set out to determine whether the same intermediates of the roGFP redox relay activated by H2O2 (Figure 1) are involved in the observed 9-HpODE-induced increase in oxidized GSH. Pretreatment of roGFP-BEAS for 2 hr with 100 μM 2-AAPA, an inhibitor of Grx, completely ablated the roGFP response to 25 μM 9-HpODE (Figure 4B). As expected, inhibition of Grx with 2-AAPA also inhibited GSSG increases induced by H2O2 (Figure 4A). 2-AAPA has also been reported to inhibit the activity of GR, an enzyme involved in the reductive pathway of roGFP (Figure 1). However, we observed no differences between the roGFP baseline fluorescence intensities for cells treated with 2-AAPA or vehicle, indicating that the levels of GSSG were unaffected following pre-treatment with 2-AAPA. Overall, these results indicated that the effect of 9-HpODE reported by roGFP is not the result of a direct interaction of 9-HpODE with the sensor and, further, suggested that the GSH oxidation induced by exposure to 9-HpODE is sensed by roGFP through Grx, as previously reported for H2O2 (24).

Figure 4. The 9-HpODE-induced oxidation of glutathione, detected by roGFP, is mediated by glutaredoxin (Grx).

roGFP-BEAS were stimulated with 25 μM of (A) H2O2 or (B) 9-HpODE at the indicated times following treatment with the Grx inhibitor 2-AAPA or a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle. Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, where each n represents an individual dish in which 5–10 distinct cells were monitored.

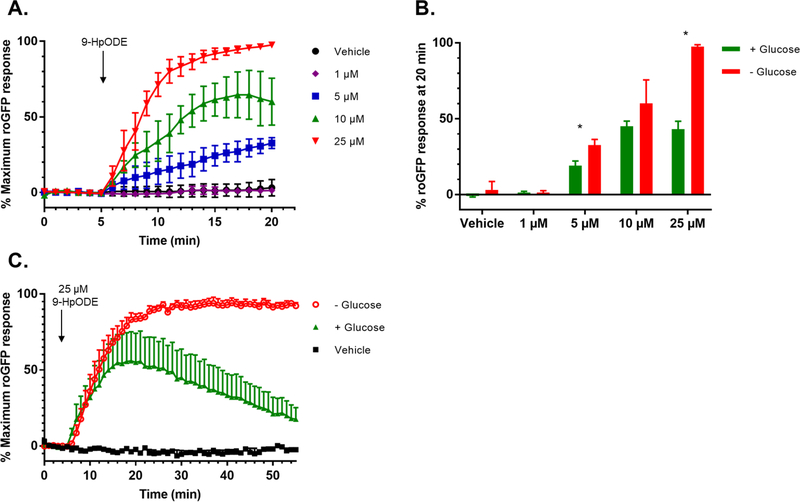

Glucose deprivation potentiates the oxidative effect of 9-HpODE on GSH and inhibits its recovery

NADPH is the major reducing equivalent used by intracellular antioxidant systems, including the reduction of GSSG to two molecules of GSH catalyzed by GR (Figure 1). Therefore, we deprived cells of glucose to impair NADPH production through the pentose phosphate pathway (38) to test its involvement in the 9-HpODE-induced GSH oxidation. roGFP-BEAS were equilibrated for 2 hr in Locke buffer without glucose as previously described by Gibbs-Flournoy et al. (39). As shown in Figure 5, glucose deprivation potentiated the formation of the oxidized form of GSH, GSSG induced by exposure of roGFP-BEAS to 5–25 μM 9-HpODE for 15 min. In addition, glucose deprivation impaired the ability of cells to adapt to an extended challenge with 9-HpODE (20–60 min), during which glucose sufficient cells showed a recovery in EGSH as reported by roGFP fluorescence (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Glucose deprivation potentiates the effects of 9-HpODE on glutathione oxidation.

A) roGFP-BEAS were deprived of glucose in Locke buffer, a minimal salt medium, for 2 hr prior to exposure to 0 – 25 μM 9-HpODE. B) Maximal roGFP response for glucose competent and glucose starved roGFP-BEAS, as measured after 15 min of exposure, in response to various doses of 9-HpODE. Bars represent the average of ≥ 2 separate dishes, where each dish is the average of 5–10 individual cells, with ± SEM. * denotes p ≤ 0.05 as determined by an unpaired t-test. C) roGFP-BEAS were deprived of glucose for 2 hr in Locke buffer prior to exposure to 25 μM 9-HpODE. All fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, where each n represents an individual dish in which 5–10 distinct cells were monitored. One sided error bars are shown for clarity.

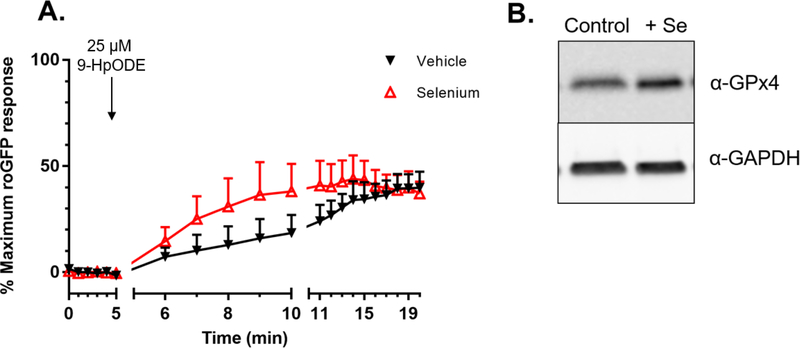

Glutathione peroxidase 4 mediates GSH oxidation specifically induced by 9-HpODE

The involvement of selenocysteine-containing GPx (40) in the GSH-dependent reduction of 9-HpODE was examined next. Figure 6A shows that a 36-hour supplementation of roGFP-BEAS with 1 μM sodium selenite accelerated the rate of the increase in GSH oxidation induced by exposure to 25 μM 9-HpODE, compared to the vehicle control. However, this change was not statistically significant (p = 0.13 for the slopes between 5 and 10 minutes, as determined by a paired t-test). Although there is some substrate overlap among the GPx family, the isoform GPx4 is mainly responsible for the reduction of long chain lipid hydroperoxides (40–42). We have previously shown that supplementation with sodium selenite increased GPx1 expression in BEAS-2B cells (39). Western blotting confirmed that roGFP-BEAS supplemented with sodium selenite also had elevated levels of GPx4 (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Selenium supplementation accelerates 9-HpODE induced glutathione oxidation.

A) roGFP-BEAS were supplemented with 1 μM sodium selenite for 36 hr to induce over-expression of glutathione peroxidases, as confirmed by western blot (B). Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to baseline and maximal sensor response. All values are presented as mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3, where each n represents an individual dish in which 5–10 distinct cells were monitored. One sided error bars are shown for clarity.

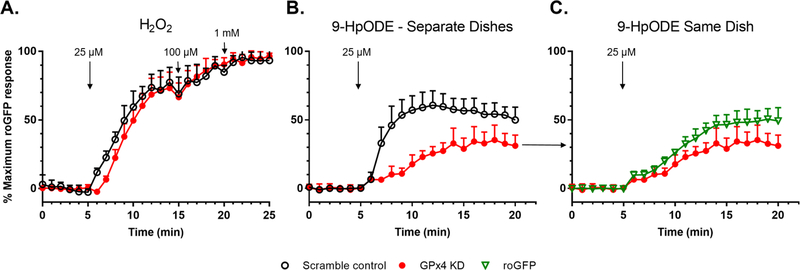

The relationship between 9-HpODE and GPx4 was further investigated utilizing an shRNA mediated knockdown of GPx4 (“GPx4 KD”). Decreased expression of GPx4 in KD cells, as compared to control cells transduced with a vector encoding a scrambled sequence, was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy and western blotting (Figure S3). Notably, the increase in GSH oxidation induced by 25 μM H2O2 in GPx4 KD cells was not different from that observed in scramble control cells (Figure 7A). In contrast, there were marked differences in the roGFP response induced by exposure to 25 μM 9-HpODE, with the GPx4 KD cells showing a slower rate of response (p= 5.59 × 10−7 for the slope between 5 and 10 minutes, as determined by unpaired t-test) and reaching a lower maximum than that observed in the scramble control cells (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4) mediates GSH oxidation specifically induced by 9-HpODE.

roGFP-BEAS transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding an shRNA to knock down expression of GPx4 (“GPx4 KD”), or a scramble control, were exposed to A) 25, 100 μM, and 1 mM H2O2 or B) 25 μM 9-HpODE. p= 5.59 × 10−7 for the slope between 5 and 10 minutes, as determined by unpaired t-test. C) GPx4 KD cells shown in panel B were compared to adjacent cells with normal GPx4 expression, identified visually by the lack of the red fluorophore that identifies the GPx4 KD cells (Figure S5). Fluorescence intensity values were normalized to the baseline and maximal sensor response. Shown are representative experiments, mean ± SD of 5–10 individual cells in each dish. Data is representative of 5–6 independent experiments. One sided error bars are shown for clarity.

The inclusion of red fluorescent protein encoded in the GPx4 vector permitted visual identification of individual GPx4 KD cells during live cell microscopic assessments of EGSH, which is reported by the green roGFP sensor (Figure S3). It was therefore possible to compare GPx4 KD cells with normal GPx4-expressing cells in the same imaging field. As shown in Figure 7C, GPx4 KD cells showed delayed and diminished GSH oxidation in response to exposure to 25 μM 9-HpODE relative to neighboring cells with normal GPx4 expression. However, this difference did not prove to be statistically significant (p = 0.14 for the slope between 5 and 10 minutes, as determined by unpaired t-test). In contrast, there were no differences between the roGFP response in GPx4 KD cells and that of the scramble controls following exposure to an equivalent dose of the low molecular weight alkyl hydroperoxide TBH (Figure S4).

Discussion

Environmental stressors such as zinc (31), 1,2-naphthoquinone (29), and ozone (39) have previously been shown to induce increases in EGSH in HAEC. While H2O2 has been demonstrated to initiate the sensing of EGSH by roGFP (24), to our knowledge, the possibility that other peroxides can also initiate the roGFP redox relay has not been addressed experimentally. We present here the first report of a long chain lipid hydroperoxide (9-HpODE) initiating intracellular GSH oxidation in intact human cells.

Although the secondary products of lipid peroxidation, such as the aldehydes HNE and MDA, have been characterized as indices of oxidative damage, lipid hydroperoxides themselves have not been well studied as mediators of cellular oxidative stress. In this study, we observed that the change in GSH oxidation is dependent on the peroxide functional group in 9-HpODE, as it did not occur with exposure to the hydroxide 9-HODE. Furthermore, a comparable increase in GSH oxidation was observed following exposure to 13-HpODE, indicating that the oxidation of GSH is not unique to the 9-HpODE isomer. This suggests that the increase in GSSG formation induced by 9-HpODE reported here can be generalized to other long chain lipid hydroperoxides. Contrary to previous reports implicating H2O2 as a mediator of HpODE bioactivity (37), our observations from direct measurement of H2O2 and catalase interventions ruled out the possibility that the oxidative effect of 9-HpODE on GSH is secondary to H2O2 production. We show here that 9-HODE, the reduced product of 9-HpODE, does not induce GSH oxidation. Further experiments in our lab have found that the aldehyde 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal also fails to induce GSH oxidation as sensed by roGFP (Corteselli unpublished). While these represent just two of many possible secondary products that might be formed from lipid peroxidation, this evidence, in combination with the involvement of GPx4, shows that lipid peroxides initiate the oxidation of GSH.

Further experiments confirmed the involvement of key enzymes in the redox relay by which the 9-HpODE-induced oxidation of GSH is reported by roGFP. Dependence on Grx, as revealed by the Grx inhibitor 2-AAPA, established that 9-HpODE does not directly oxidize the roGFP sensor, while selenium supplementation implicated the family of selenocysteine-containing GPx in the initial reduction of 9-HpODE. Due to the ability of GPx4 to reduce long chain lipid hydroperoxides, we specifically investigated the involvement of GPx4 in HAEC in the reduction of 9-HpODE at the expense of GSH. shRNA-mediated knockdown of GPx4 revealed that this enzyme is, in fact, involved in the roGFP response induced by exposure to 9-HpODE, but not by equivalent doses of H2O2 or the low molecular weight alkyl hydroperoxide TBH. This may be explained by the ability of GPx1 to reduce H2O2 and TBH, but not more complex and less soluble peroxides such as 9-HpODE (40, 42). Together, these data demonstrate that long chain lipid hydroperoxides oxidize GSH largely through the peroxidatic activity of GPx4.

Experiments conducted in acellular systems have previously shown that incubation of various cysteine-containing enzymes with linoleic acid resulted in their inactivation (43–45). More recent studies by Poole and colleagues have observed that a cysteine-containing thiol peroxidase (Tpx) from E. coli is sulfenylated as part of its catalytic cycle by both the aromatic hydroperoxide cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) and the long chain hydroperoxide 15-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (46). Further experiments utilizing a genetically encoded probe for detection of cysteine sulfenic acid protein modifications revealed that global sulfenylation is induced by both CHP and TBH in E. coli cells (47). Furthermore, preliminary data from our lab has confirmed that TBH induces sulfenylation of recombinant human GAPDH in vitro independently of H2O2 (Corteselli, unpublished). GAPDH has been shown to be susceptible to thiol modifications at its catalytic cysteine (48), and previous studies have hypothesized that during exposure to high levels of ROS, the sulfenylation and resulting inactivation of GAPDH functions to divert glucose metabolism to the pentose phosphate pathway in order to increase the production of NADPH to sustain antioxidant systems (49). The oxidant inactivation of GAPDH may also explain the EGSH recovery observed following treatment with 9-HpODE in glucose sufficient cells, which, in agreement with our data, would not be possible in the glucose deprived cells. In addition to functioning as a sensor of EGSH, roGFP may be considered a stand-in for cellular thiol-containing proteins that may be oxidized by exposure to 9-HpODE. However, the sulfenylation of other protein cysteines by lipid hydroperoxides, such as those in GAPDH, in intact human cells requires further investigation. In support of this line of research, we recently observed that another thiol-containing antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), ablates the effect of 9-HpODE on GSH oxidation when co-administered, presumably by sparing thiol-containing cellular targets. On the other hand, overnight supplementation with NAC, which has been demonstrated to increase intracellular GSH stores (50, 51) did not change the EGSH increase induced by 9-HpODE (Corteselli, unpublished). This is consistent with the notion that the sensing of Egsh by roGFP is primarily driven by the formation of GSSG (24).

Previous reports have also implicated lipid hydroperoxides in the activation of receptors and alteration of signaling cascades. Metabolites of arachidonic acid, the hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) (52), as well as 9- and 13-HODE present on oxidized LDL (53) have been shown to activate peroxisome proliferation activated receptors (PPARs). 13-HpODE was also found to activate PPAR-α in rat, though not human, hepatoma cells (54). Additionally, 13-HpODE has been shown to alter epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling (55) in vitro. These findings raise the possibility that the oxidation of GSH by 9-HpODE observed in this study occurs secondary to receptor binding and/or activation of signaling pathways. H2O2 is the most plausible effector that might be generated from either of these mechanisms capable of mediating an alteration of EGSH, reported by roGFP. However, the catalase-based interventions designed to scrub excess H2O2 from both the extracellular and intracellular spaces resulted in no change in GSH oxidation induced by 9-HpODE. Additionally, direct monitoring utilizing HyPer found no increase in the concentration of H2O2 in BEAS-2B cells following exposure to 9-HpODE. These data demonstrate that the oxidation of GSH by 9-HpODE is independent of H2O2, and therefore most likely independent of receptor-mediated effects of 9-HpODE.

It is also possible that, due to the self-propagating nature of lipid peroxidation, exposure to 9-HpODE in this study resulted in de novo production of lipid hydroperoxides that might contribute to the oxidation of GSH. Lipid hydroperoxides can be reduced by transition metals such as Fe2+ to form alkoxyl (LO·) or peroxyl (LOO·) radicals, which can propagate lipid peroxidation via hydrogen abstraction or rearrange to form epoxides, endoperoxides, or carbonyls (35, 56). The possibility that the degradation of exogenously introduced 9-HpODE induced by transition metals present in the culture medium and cells contributed to oxidizing products cannot be excluded. In the end, however, any such products would be required to be substrates of GPx4 in order to cause the GSH oxidation observed in this study.

A similar potential mechanism for the indirect oxidation of GSH initiated by 9-HpODE is the activation of enzymes associated with eicosanoid production, such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (57), or LOX (58). Several eicosanoid intermediates of LOX catalysis of arachidonic acid oxidation are in fact lipid hydroperoxides (59). It is therefore plausible that an eicosanoid hydroperoxide species is responsible for the observed increase in GSH oxidation. We point out that in this case as well, the effector molecule that oxidizes GSH would be a lipid hydroperoxide substrate of GPx4. Further study is necessary in order to distinguish between an exogenous or endogenous source of lipid hydroperoxide, or some combination thereof, in the GSH oxidation induced by 9-HpODE.

In this study, lentiviral-mediated expression of an shRNA directed at GPx4 in BEAS-2B cells resulted in a significant reduction in GPx4 protein that was correlated with a substantial reduction of the 9-HpODE-induced increase in GSH oxidation. Broadly, the involvement of a selenium-containing GPx in 9-HpODE-induced GSH oxidation is further supported by the observed increase in the rate of the roGFP response following overnight supplementation with selenium. However, it is possible that other lipid hydroperoxide scavenging enzymes such as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) (60) and peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6) (61) contribute to GSH oxidation in 9-HpODE-exposed BEAS-2B cells. Reduction of 9-HpODE by GST would be expected to generate GSSG and thus increase Egsh. However, GSSG formation secondary to the reduction of 9-HpODE by Prdx6, a 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin, is dependent first on gluthathionylation by πGST (61). The potential involvement of Prdx6 or GST in the sensing of GSH oxidation by roGFP has not been previously investigated. However, the increased rate of GSH oxidation in selenium supplemented cells observed in our study supports the primary involvement of a glutathione peroxidase rather than Prdx6 or GST, which do not contain selenocysteines. Any future assessment of the relative contributions of GPx4, GST, and Prdx6 in mediating GSH oxidation initiated by 9-HpODE would require consideration of the potential compensatory effects and adaptive responses to modulated expression of one or more of these enzymes.

In the present study we investigated the effect of a biologically relevant long chain lipid hydroperoxide on cytosolic GSH oxidation in HAEC using the fluorogenic sensor roGFP. Our findings highlight the role of primary lipid peroxidation products as effectors, rather than transient intermediates, in cellular oxidative reactions. Our finding that lipid hydroperoxides have a direct effect on the major intracellular mechanism of redox homeostasis sheds light on a previously unrecognized effect of lipid peroxidation. The disruption of cellular oxidative state by lipid hydroperoxides may provide insight into the variety of disease states that involve lipid peroxidation in their pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Fatty acid peroxidation is an important process in normal and pathophysiology

Lipid hydroperoxide 9-HpODE induces GSH oxidation sensed by roGFP

9-HpODE-induced GSH oxidation is independent of secondary products or H2O2

GPx4 mediates 9-HpODE but not H2O2 or shorter hydroperoxide induced GSH oxidation

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Katelyn Lavrich for assistance with experimental design.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by EPA-UNC Toxicology Training Agreement [Grant CR-83591401-0] and the NIEHS [NRSA F31 ES029020].

Abbreviations

- EGSH

Glutathione redox potential

- 9-HpODE

9-hydroperoxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid

- 9-HODE

9-hydroxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- HAEC

Human airway epithelial cells

- GPx4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- TBH

tert-butyl hydroperoxide

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The research described in this article has been reviewed by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. The contents of this article should not be construed to represent agency policy nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Catalá A. 2009. Lipid peroxidation of membrane phospholipids generates hydroxy-alkenals and oxidized phospholipids active in physiological and/or pathological conditions. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 157 (1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freigang S. 2016. The regulation of inflammation by oxidized phospholipids. European Journal of Immunology. 46 (8):1818–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girotti AW. 1998. Lipid hydroperoxide generation, turnover, and effector action in biological systems. Journal of Lipid Research. 39 (8):1529–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zmijewski J, Landar A, Watanabe N, Dickinson D, Noguchi N, Darley-Usmar V. 2005. Cell signalling by oxidized lipids and the role of reactive oxygen species in the endothelium. Biochemical Society Transactions. 33 (6):1385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu S. 2008. F2-isoprostanes in Human Health and Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 10 (8):1405–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Forman HJ. 2017. 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated signaling and aging. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 111:219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel RB, Kotha SR, Sherwani SI, Sliman SM, Gurney TO, Loar B, et al. 2011. Pulmonary Fibrosis Inducer, Bleomycin, Causes Redox-Sensitive Activation of Phospholipase D and Cytotoxicity Through Formation of Bioactive Lipid Signal Mediator, Phosphatidic Acid, in Lung Microvascular Endothelial Cells. International Journal of Toxicology. 30 (1):69–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Xia Q, Yin J-J, Yu H, Fu PP. 2011. Photoirradiation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon diones by UVA light leading to lipid peroxidation. Chemosphere. 85 (1):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butterfield DA, Lauderback CM. 2002. Lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease brain: Potential causes and consequences involving amyloid β-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 32 (11):1050–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CM, Wu YR, Cheng ML, Liu JL, Lee YM, Lee PW, et al. 2007. Increased oxidative damage and mitochondrial abnormalities in the peripheral blood of Huntington’s disease patients. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 359 (2):335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esterbauer H, Gebicki J, Puhl H, Jürgens G. 1992. The role of lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in oxidative modification of LDL. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 13 (4):341–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulthe J, Fagerberg B. 2002. Circulating oxidized LDL is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis development and inflammatory cytokines (AIR Study). Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 22 (7):1162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg D. 2009. The LDL modification hypothesis of atherogenesis: an update. Journal of Lipid Research. 50 (Supplement):S376–S81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niki E, Yoshida Y, Saito Y, Noguchi N. 2005. Lipid peroxidation: Mechanisms, inhibition, and biological effects. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 338 (1):668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter NA, Caldwell SE, Mills KA. 1995. Mechanisms of free radical oxidation of unsaturated lipids. Lipids. 30 (4):277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider C, Pratt DA, Porter NA, Brash AR. 2007. Control of Oxygenation in Lipoxygenase and Cyclooxygenase Catalysis. Chemistry & Biology. 14 (5):473–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. 2000. Cyclooxygenases: Structural, Cellular, and Molecular Biology. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 69 (1):145–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SH, Blair IA. 2000. Characterization of 4-oxo-2-nonenal as a novel product of lipid peroxidation. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 13 (8):698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pryor WA, Porter NA. 1990. Suggested mechanisms for the production of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal from the autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 8 (6):541–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uchida K. 2003. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Progress in Lipid Research. 42 (4):318–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedli O, Freigang S. 2017. Cyclopentenone-containing oxidized phospholipids and their isoprostanes as pro-resolving mediators of inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1862 (4):382–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida Y, Umeno A, Shichiri M. 2013. Lipid peroxidation biomarkers for evaluating oxidative stress and assessing antioxidant capacity in vivo. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 52 (1):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sies H. 1999. Glutathione and its role in cellular functions. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 27 (9–10):916–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer AJ, Dick TP. 2010. Fluorescent protein-based redox probes. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 13 (5):621–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jira W, Spiteller G, Carson W, Schramm A. 1998. Strong increase in hydroxy fatty acids derived from linoleic acid in human low density lipoproteins of atherosclerotic patients. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 91 (1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadana T, Dhall K, Sanyal S, Wali A, Minocha R, Majumdar S. 1988. Isolation and chemical composition of surface-active material from human lung lavage. Lipids. 23 (6):551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly FJ. 2003. Oxidative stress: its role in air pollution and adverse health effects. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (8):612–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddel RR, Ke Y, Gerwin BI, McMenamin MG, Lechner JF, Su RT, et al. 1988. Transformation of Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells by Infection with SV40 or Adenovirus-12 SV40 Hybrid Virus, or Transfection via Strontium Phosphate Coprecipitation with a Plasmid Containing SV40 Early Region Genes. Cancer Research. 48 (7):1904–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng WY, Currier J, Bromberg PA, Silbajoris R, Simmons SO, Samet JM. 2012. Linking Oxidative Events to Inflammatory and Adaptive Gene Expression Induced by Exposure to an Organic Particulate Matter Component. Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (2):267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavrich KS, Corteselli EM, Wages PA, Bromberg PA, Simmons SO, Gibbs-Flournoy EA, et al. 2018. Investigating mitochondrial dysfunction in human lung cells exposed to redox-active PM components. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 342:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wages PA, Silbajoris R, Speen A, Brighton L, Henriquez A, Tong H, et al. 2014. Role of H2O2 in the oxidative effects of zinc exposure in human airway epithelial cells. Redox Biology. 3:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devlin R, McKinnon K, Noah T, Becker S, Koren H. 1994. Ozone-induced release of cytokines and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 266 (6):L612–L9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkman HN, Gaetani GF. 1984. Catalase: a tetrameric enzyme with four tightly bound molecules of NADPH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 81 (14):4343–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor‐Clark TE, Undem BJ. 2010. Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. The Journal of Physiology. 588 (3):423–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng Z, Li Y. 2007. What is Responsible for the Initiating Chemistry of Iron-Mediated Lipid Peroxidation: An Update. Chemical Reviews. 107 (3):748–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meilhac O, Zhou M, Santanam N, Parthasarathy S. 2000. Lipid peroxides induce expression of catalase in cultured vascular cells. Journal of Lipid Research. 41 (8):1205–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santanam N, Augé N, Zhou M, Keshava C, Parthasarathy S. 1999. Overexpression of Human Catalase Gene Decreases Oxidized Lipid-Induced Cytotoxicity in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 19 (8):1912–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stincone A, Prigione A, Cramer T, Wamelink M, Campbell K, Cheung E, et al. 2015. The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biological Reviews. 90 (3):927–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibbs-Flournoy EA, Simmons SO, Bromberg PA, Dick TP, Samet JM. 2013. Monitoring Intracellular Redox Changes in Ozone-Exposed Airway Epithelial Cells. Environmental Health Perspectives 121 (3):312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brigelius-Flohé R, Maiorino M. 2013. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects. 1830 (5):3289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imai H, Nakagawa Y. 2003. Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 34 (2):145–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toppo S, Flohé L, Ursini F, Vanin S, Maiorino M. 2009. Catalytic mechanisms and specificities of glutathione peroxidases: Variations of a basic scheme. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects. 1790 (11):1486–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis SE, Wills E. 1962. The destruction of—SH groups of proteins and amino acids by peroxides of unsaturated fatty acids. Biochemical Pharmacology. 11 (10):901–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little C, O’Brien P. 1968. The effectiveness of a lipid peroxide in oxidizing protein and non-protein thiols. Biochemical Journal. 106 (2):419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wills E. 1961. Effect of unsaturated fatty acids and their peroxides on enzymes. Biochemical Pharmacology. 7 (1):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker LM, Poole LB. 2003. Catalytic Mechanism of Thiol Peroxidase from Escherichia coli SULFENIC ACID FORMATION AND OVEROXIDATION OF ESSENTIAL CYS61. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (11):9203–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takanishi CL, Ma L-H, Wood MJ. 2007. A Genetically Encoded Probe for Cysteine Sulfenic Acid Protein Modification in Vivo. Biochemistry. 46 (50):14725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hancock JT, Henson D, Nyirenda M, Desikan R, Harrison J, Lewis M, et al. 2005. Proteomic identification of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase as an inhibitory target of hydrogen peroxide in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 43 (9):828–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hildebrandt T, Knuesting J, Berndt C, Morgan B, Scheibe R. 2015. Cytosolic thiol switches regulating basic cellular functions: GAPDH as an information hub? Biological Chemistry. 396 (5):523–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrari G, Yan C, Greene L. 1995. N-acetylcysteine (D-and L-stereoisomers) prevents apoptotic death of neuronal cells. J Neurosci. 15 (4):2857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang J, Jahraus B, Balta E, Huebner K, Blank N, Niesler B, et al. 2018. Sulforaphane Inhibits Inflammatory Responses of Primary Human T-Cells by Increasing ROS and Depleting Glutathione. Front Immunol. 9:2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu K, Bayona W, Kallen CB, Harding HP, Ravera CP, McMahon G, et al. 1995. Differential Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors by Eicosanoids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (41):23975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. 1998. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ. Cell. 93 (2):229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.König B, Eder K. 2006. Differential action of 13-HPODE on PPARα downstream genes in rat Fao and human HepG2 hepatoma cell lines. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 17 (6):410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hui R, Kameda H, Risinger J, Angerman-Stewart J, Han B, Barrett JC, et al. 1999. The linoleic acid metabolite, 13-HpODE augments the phosphorylation of EGF receptor and SHP-2 leading to their increased association. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 61 (2):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davies SS, Guo L. 2014. Lipid peroxidation generates biologically active phospholipids including oxidatively N-modified phospholipids. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 181:1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burke JE, Dennis EA. 2009. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling. Journal of Lipid Research. 50 (Supplement):S237–S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hemler ME, Cook HW, Lands WE. 1979. Prostaglandin biosynthesis can be triggered by lipid peroxides. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 193 (2):340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Leary V, Darley-Usmar V, Russell L, Stone D. 1992. Pro-oxidant effects of lipoxygenase-derived peroxides on the copper-initiated oxidation of low-density lipoprotein. Biochemical Journal. 282 (3):631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine: Oxford University Press, USA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher AB. 2017. Peroxiredoxin 6 in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes and cell signaling. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 617:68–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.