Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence and mortality have shown an unfavorable upward trend over the last two decades, especially in developed countries. More than one-sixth of the patients have advanced HCC at presentation. Systemic therapy remains the treatment of choice for these patients. Current options include tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immunotherapy. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on the rapidly evolving field of systemic therapy with several newly approved medications over the last year. Sorafenib remains one of the first-line treatment choices for patients with hepatitis C etiology, intermediate to advanced HCC stage, and Child-Pugh class A. Lenvatinib is the other first-line drug that might have better efficacy in non–hepatitis C etiologies and advanced HCC without portal vein thrombosis. Patients intolerant to first-line therapy might benefit from immunotherapy with nivolumab or pembrolizumab. In those who fail first-line therapy, the choice should be based on the side effects related to previous treatment, performance status, and underlying liver dysfunction. Ongoing studies are investigating immunotherapy alone or immunotherapy in combination with TKIs as first-line therapy. Several second-line options for combination systemic therapy and systemic plus local-regional treatment are under investigation. Future studies should focus on identifying reliable biomarkers to predict response to therapy and to better stratify patients at high risk for progression. Multidisciplinary approach is pivotal for successful outcomes in patients with advanced HCC.

Keywords: systemic therapy, HCC, immunotherapy, combination therapy

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CI, confidence interval; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; irAE, immune-related adverse events; LRT, local-regional therapy; LT, liver transplantation; OS, overall survival; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PD-1, programmed cell death-1; PFS, progression-free survival; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse effect; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TTP, time to progression; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Over the last 25 years, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence has shown continuous rise worldwide and is more pronounced in developed countries.1 HCC remains a leading causes of cancer-related mortality in the USA.2 The estimated 1- and 2-year survival of untreated HCC is 17.5% and 7.3%, respectively.3 Although there has been an increase in early-diagnosed HCC, 16% have distant metastases at the time of presentation and 85% have lymphovascular invasion on final pathology.4 Systemic chemotherapy remains the treatment of choice for patients with advanced HCC who are not suitable for resection, liver transplantation (LT), or local-regional therapy (LRT). The aim of this review is to update and summarize knowledge on currently approved systemic therapies for advanced HCC in the light of several recent medication approvals and to provide guidance on treatment selection.

Current systemic therapy of HCC consists of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and checkpoint inhibitors. Kinases are a class of enzymes that catalyze the transfer of phosphate groups from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) onto amino acid residues (tyrosine, serine, and threonine) of key proteins, which results in signal transduction associated with cell differentiation, proliferation, or death.5 Overexpression of their receptors, in particular of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in various cancers, has led to the development of more than 20 TKI drugs. RTKs act as receptors for growth factors, cytokines, hormones, and other extracellular signaling molecules that activate them after binding to their extracellular domain.6 Some of the most important RTK subfamilies are vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (c-KIT), and hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET). Alterations of RTKs could result in deregulation of signaling pathways, thus triggering cell proliferation and tumor formation.7 TKIs compete with ATP for ATP-binding sites and decrease tyrosine kinase phosphorylation that leads to inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and stimulation of tumor cell apoptosis.

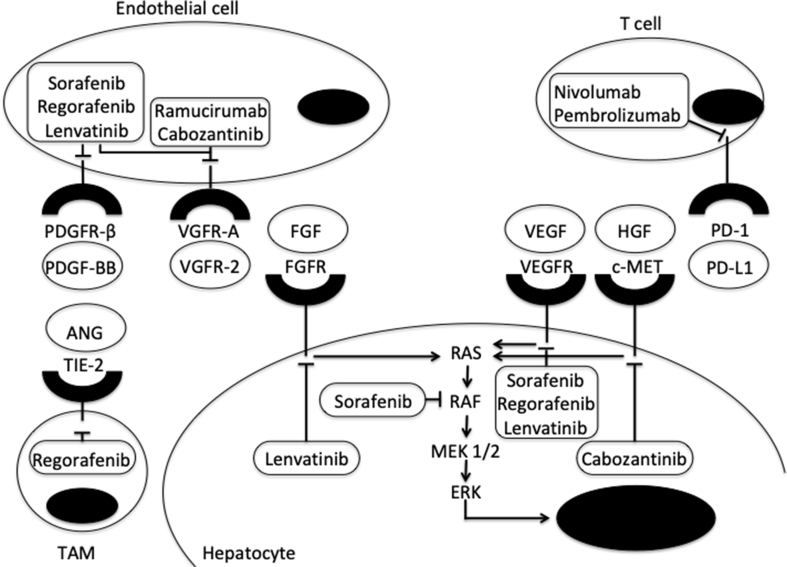

Over the last decade, immune checkpoint inhibitors have emerged as a promising treatment in cancer therapy. Their effect is based on targeting immune checkpoint receptors that are negative regulators of antitumor immunity and are upregulated in tumor tissues.8 The result is activation of preexisting cytotoxic T lymphocytes. These agents may result in long-lasting tumor regression even in diffusely metastatic cancers. The antibodies identified to date that trigger antitumor immune response target the cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) or programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) pathways. CTLA-4 affects T-cell activity and proliferation, mainly in the priming phase of the immune response in lymph nodes, whereas PD-1 acts during the effector phase, predominantly in peripheral tissues.9 A major concern with this therapy remains immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that could affect the colon, liver, lungs, thyroid gland, pituitary, heart, nervous system, and skin.10 Although irAEs can be usually managed with discontinuation of chemotherapy and corticosteroids therapy, a recent meta-analysis reported that fatal toxic events can occur in 0.3%–1.3% of treated patients, mainly in the early phases of treatment.11 The most common targets and mechanism of action of currently approved medications for treatment of advanced HCC are showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of currently approved drugs of HCC and their cell signaling pathways. Tyrosine kinases receptors have an extracellular domain that binds to specific homologous ligands (represented in ovals), transmembrane part, and an intracellular domain that binds to and phosphorylates tyrosine residues of target proteins, thus activating signaling pathways. The activated RAF/MEK/ERK serine/threonine kinase cascade plays a key role in cell proliferation and differentiation and controls survival-related genes. ANG, angiopoietin; c-MET, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HGF; hepatocyte growth factor; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PD-1, programmed cell death-1; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

First-line therapies

Sorafenib

Sorafenib (Nexavar®; Bayer, Germany) was discovered in the late 1990s and approved for first-line treatment of advanced HCC in the USA in 2007 and later worldwide. It has remained the standard of care and the only available option for treatment of advanced HCC for more than 10 years. Sorafenib is an oral multitargeted TKI with antiangiogenic, apoptotic, and antiproliferative activity.12 It inhibits serine-threonine kinases: wild-type and mutant B-Raf as well as Raf1 (or C-Raf) and directly blocks autophosphorylation of RTKs for VEGFRs 1, 2, and 3 and PDGFR-β, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT-3), c-KIT, and rearranged during transfection (RET).13 Sorafenib approval was based on a multicenter, phase 3, randomized controlled trial (RCT) Sorafenib HCC Assessment Randomized Protocol (SHARP)14 that showed benefit on median overall survival (OS) and delay in radiologic progression (Table 1). A phase 3 study based on Asian population confirmed its beneficial effect in this cohort as well.15

Table 1.

Main Trials Results of Currently Approved Medications for Advanced HCC.

| Clinical trial | Overall survival (months) | Objective responsea | Drug-related adverse events (grade 3/4) | Permanent discontinuation due to adverse events | Dose reduction due to adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib vs. placebo SHARP14 Phase 3 |

10.7 vs. 7.9; HR, 0.69 (CI, 0.55–0.87) P < 0.001 |

2% vs 1% | Diarrhea, HFSR, hypertension, abdominal pain | 11% vs 5% | 26% vs 7% |

| Sorafenib vs. placebo Asian-Pacific15 Phase 3 |

6.5 vs. 4.2; HR, 0.68 (CI, 0.50–0.93) P = 0.014 |

3.3% vs 1.3% | HFSR, diarrhea, fatigue, hypertension | 20% vs 13% | 31% vs 3% |

| Lenvatinib vs. sorafenib REFLECT28 Phase 3 |

13.6 vs. 12.3; HR, 0.92 (CI, 0.79–1.06) |

24% vs 9% | 57% lenvatinib vs 49% sorafenib | 9% vs 7% | 37% vs 38% |

| Regorafenib vs. placebo RESORCE30 Phase 3 |

10.6 vs. 7.8; HR, 0.63 (CI, 0.50–0.79) P < 0.0001 |

11% vs 4% | Hypertension, HFSR, fatigue, diarrhea | 10% vs 4% | 54% vs 10% |

| Cabozantinib vs. placebo CELESTIAL37 Phase 3 |

10.2 vs. 8.0; HR, 0.76 (CI, 0.63–0.92) P = 0.005 |

4% vs <1% | HFSR, hypertension, AST increase, diarrhea | 16% vs 3% | 62% vs 13% |

| Nivolumab CheckMate 04041 Phase 1/2 |

– | 15% in dose escalation 20% in dose-expansion phase |

AST and ALT increase, lipase and amylase increase, pruritus | 11% | – |

| Pembrolizumab KEYNOTE-22442 Phase 2 |

– | 17% | Fatigue, AST and ALT increase, hyperbilirubinemia, adrenal insufficiency | 5% | – |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, 95% confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HFSR, hand-foot skin reaction; HR, hazard ratio.

The percentage of patients with complete or partial response.

Two real-life observational studies assessed the use of sorafenib in different populations of patients with HCC.16, 17 Global Investigation of therapeutic Decisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and Of its treatment with sorafeNib (GIDEON)16 demonstrated better OS of Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class A patients (13.6 months) than that of CTP class B (5.2 months) and CTP class C (2.6 months) patients. The safety profile was similar between groups. SOraFenib Italian Assessment (SOFIA)17 showed greater benefit in patients with less advanced tumors based on Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system: Those with BCLC-B responded better than BCLC-C group. Overall, 40% of patients in this study discontinued sorafenib because of side effects. Advanced Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, macrovascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, early radiologic progression at 2 months, and sorafenib dose were independent predictors of mortality.

An analysis based on pooled data from the SHARP and Asian-Pacific trials noted that patients with HCC without extrahepatic spread, with hepatitis C virus (HCV) etiology, and low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio had the greatest benefit of sorafenib therapy.18 Another prognostic factor was development of hand-foot skin reaction of grade 2 or more within 60 days of sorafenib initiation which was associated with significant decrease in mortality.19 Meta-analysis based on more than 2000 patients confirmed that dermatological adverse events due to sorafenib were associated with longer survival.20

The rationale for combining LRT with sorafenib is based on previous evidence that transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) could cause hypoxia, enhanced microvessel density, and increased VEGF expression in HCC cells.21 However, clinical trials to date have shown conflicting results. A recent meta-analysis based on 27 studies published over the last eight years demonstrated that the combination of sorafenib with TACE vs. TACE alone was superior in terms of time to progression (TTP), but not for OS.22 An open-label phase 2 trial that investigated the benefit of TACE plus sorafenib (started 2–3 weeks before the procedure) vs. TACE alone (TACTICS trial)23 in patients with good performance status, CTP score ≤7, and intermediate-stage HCC (BCLC-B) showed promising results with improved progression-free survival (PFS) in combination group vs. TACE alone (25.2 vs 13.5 months) and TTP (26.7 vs 16.4 months; HR 0.54), but the results of OS are pending. A different design was used in a phase 3 trial that compared sorafenib vs. TACE plus sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC who failed LRT (sorafenib with or without cTACE in patients with advanced HCC (STAH) trial).24 There was no improvement in OS, although all secondary outcomes such as PFS, TTP, and tumor response rate were significantly longer in the sorafenib + TACE group.

The effect of selective internal radiation therapy vs. sorafenib was assessed in a phase 2 RCT SORAfenib in combination with local MICrotherapy guided by gadolinium-EOB-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (SORAMIC), which did not show benefit in OS between the two groups, but in a subgroup analysis, yttrium-90 + sorafenib improved OS in patients younger than 65 years, in those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease etiology, and in those without cirrhosis.25

Overall, sorafenib has shown to be more efficacious in patients with HCV, intermediate to advanced HCC stage, and CTP class A. Patients who experience hand-foot reaction seem to respond better to therapy, but this remains to be proven. Although no significant difference in safety was found in most studies, patients with more advanced liver disease showed a greater number of adverse events, requiring dose reduction or drug discontinuation.

Lenvatinib

Lenvatinib (Lenvima®; Eisai Inc., Japan) is a multitargeted TKI that inhibits VEGFR1-3, PDGFR-α, RET, and KIT. The distinctive feature of this molecule is the additional inhibition of FGFRs 1–4 of HCC tumor cells.26 A recent study that used an animal model of HCC noted that lenvatinib had immunomodulatory activity that enhanced its antitumor effect, especially when combined with anti–PD-1 antibody.27 In 2018, lenvatinib was approved for first-line therapy of HCC initially in Japan and later in the USA, Europe, and China. The approval was based on the results of a randomized, open-label, phase 3 noninferiority trial comparing lenvatinib 12 mg for body weight ≥60 kg and 8 mg for body weight <60 kg and sorafenib 400 mg twice daily (REFLECT trial).28 Patients with unresectable HCC, BCLC-B and C, CTP class A, and no prior systemic treatment were included. The study did not enroll patients with >50% liver involvement and/or main portal vein or biliary invasion. Lenvatinib showed noninferiority regarding mean OS but did not reach superiority. There was statistically significant improvement with lenvatinib in all secondary efficacy endpoints: longer median PFS and TTP as well as greater objective response. Lenvatinib demonstrated greater benefit in OS in those with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) ≥ 200 ng/ml, although patients were not stratified by AFP level at enrollment. Subgroup analyses showed it was less effective in patients from Western countries, without extrahepatic spread, and with HCV etiology. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effect (TEAE) was hypertension. After correction for treatment duration, TEAEs were comparable between arms. However, there was delayed deterioration in the quality of life of patients taking lenvatinib. More than one-third of the patients in this trial received poststudy treatment after failure of the studied medications. Among those, median OS was 21 and 17 months and objective response rate was 27.6% and 8.7% in lenvatinib vs. sorafenib arms, respectively.

Currently, a large phase 3 trial is assessing the efficacy of a combination of lenvatinib with pembrolizumab as first-line therapy (NCT03713593) and a phase 1 trial is assessing the efficacy of a combination of lenvatinib with nivolumab (NCT03418922).

Second-line therapies

Regorafenib

Regorafenib (Stivarga® Bayer, Germany) is a multitargeted TKI with very similar structure as sorafenib, but it is considered a second-generation drug because of its improved target affinity and higher potency. It blocks the activity of angiogenic (VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, and tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor (TIE-2)), stromal (PDGFR-β and FGFR), and oncogenic (Raf, RET, and c-KIT) RTKs.29 Regorafenib was approved in the USA and Europe in 2017 for patients who failed sorafenib therapy. The approval was based on the positive results of a phase 3 RCT that compared regorafenib 160 mg daily with placebo administered 3 weeks per month with one week off in patients who progressed on sorafenib (Regorafenib after sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (RESORCE) trial).30 The studied population consisted of patients with a good performance status (ECOG 0 and 1); most had advanced HCC (BCLC-C) and preserved liver function (CTP class A). In comparison with prior trials, patients were stratified by AFP level, vascular invasion, and extrahepatic spread. This was prompted by an analysis that demonstrated the endpoint for discontinuing first-line therapy should be radiological and not symptomatic progression and that there was an association between patterns of progression and postprogression survival, with new extrahepatic nodule being the strongest predictor of radiologic tumor progression.31 Only patients who tolerated sorafenib were included in the trial, and the reason for discontinuation had to be radiological progression.30 Regorafenib met the primary endpoint with a median OS of 10.6 months in the regorafenib arm vs. 7.8 months in the placebo arm. The OS favored regorafenib in all subgroups, especially in patients <65 years and/or with extrahepatic spread, CTP class A score 5, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) etiology. The TEAEs of regorafenib were similar to those of sorafenib.

A secondary analysis of the RESORCE trial demonstrated that regorafenib provided benefit on OS irrespective of the last sorafenib dose or TTP on sorafenib with no significant differences in safety.32 The median OS was 26 months in the sorafenib-regorafenib group compared with 19 months in the sorafenib-placebo group. This beneficial effect suggests patients with progressive HCC, despite LRT, should be started on systemic therapy early, while liver function is preserved, and should be considered for second-line therapy, despite disease progression. On the other hand, cost-effective analyses showed only modest incremental benefit at a relatively high incremental cost, suggesting regorafenib treatment is not cost-effective and patients should be carefully selected before being considered for therapy.33

A recent analysis of plasma and tissue samples of participants of RESORCE trial suggested five proteins known to play a role in inflammation and in HCC pathogenesis, and nine microRNAs could be potentially used as prognostic markers for increased OS after regorafenib therapy.34 Interestingly, neither AFP nor c-MET was predictive of treatment benefit.

Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib (Cabometyx®; Exelixis Inc., USA) is a TKI that inhibits VEGFR2, c-MET, and AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK implicated in metastases development).35 High level of phosphorylated c-MET has been associated with resistance to sorafenib, and blockade of c-MET by cabozantinib was shown to overcome this in tissue models.36 Cabozantinib was approved as a second-line treatment for advanced HCC in January 2019. The approval was based on a phase 3 RCT that assessed the effect of cabozantinib 60 mg vs. placebo in patients previously treated with sorafenib (cabozantinib (XL184) vs placebo in subjects with hepatocellular carcinoma who have received prior sorafenib (CELESTIAL) trial).37 Compared with patients included in the RESORCE trial, the CELESTIAL trial enrolled patients who failed up to two previous systemic treatments including prior immunotherapy, with >50% liver involvement, biliary or portal vein invasion. Of note, more patients with macrovascular invasion were included in the placebo group than in the cabozantinib group (34% vs 27%, respectively). Cabozantinib met the primary outcome at the second interim analysis, and the trial was stopped prematurely. Median OS for cabozantinib was 10.2 months vs 8.0 months in the placebo arm. Median PFS and objective response also showed statistically significant improvement. In subgroup analyses, cabozantinib demonstrated favorable effects in patients ≥65 years, males, those with ECOG 0, those with AFP ≥400 ng/ml, those with extrahepatic spread, non-Asian population, and those with HBV etiology. The discordance of a lack of benefit among Asians who are known to have higher prevalence of HBV-related HCC while showing benefit in HCC due to HBV in the registration trial highlights the need for future studies in different cohorts of patients. Cabozantinib did not show benefit on OS in those who failed two prior systemic regimens (hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–1.29) and likely will not be useful as a third-line therapy. The most common TEAEs leading to dose reduction were hand-foot syndrome, diarrhea, fatigue, and hypertension.

Ramucirumab

Ramucirumab (Cyramza®; Eli Lilly, USA) is a recombinant IgG1 monoclonal antibody that inhibits VEGFR2. A phase 3 RCT compared intravenous ramucirumab 8 mg/kg vs placebo every 2 weeks in addition to best supportive care in patients who failed or were intolerant to sorafenib (REACH).38 The study was negative in terms of OS, but subgroup analyses showed benefit in patients with baseline AFP ≥400 ng/ml. An exploratory analysis of this trial suggested this effect could be observed only in CTP class A patients.39 Based on these results, a phase 3 RCT assessed the effect of ramucirumab vs. placebo in well-compensated patients with advanced HCC and AFP ≥400 ng/ml (REACH-2).40 Ramucirumab achieved survival benefit over placebo although the difference in median OS was only 1.2 months (8.5 vs 7.3 months, respectively). The most common adverse effects were hypertension, fatigue, peripheral edema, and ascites. Of note, 3% of patients in both studies had adverse events leading to death. Ramucirumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a second-line agent in patients with AFP ≥400 ng/ml in May this year.

Immunotherapy

Nivolumab

Nivolumab (Opdivo®; Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., USA) is a fully human IgG4 PD-1 antibody. It is the first approved immunotherapy for HCC that received an accelerated approval for a second-line therapy in the USA in 2017. Nivolumab was tested in an open-label, noncomparative, phase 1/2 dose study (CheckMate 040) that assessed the safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with HCC with or without HCV or HBV who failed sorafenib or other systemic therapy and those who were intolerant to or refused sorafenib.41 The objective response rate was 20% in patients who received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks with a total of six patients achieving complete response. Most of the responses occurred early, within the first 3 months of treatment. Stable disease was noted in 45% that lasted at least 6 months. There was no difference in the objective response among different etiologies and regardless of the percentage of PD-1 expression on tumor cells. The most common TEAEs were rash, elevated transaminases, amylase and lipase increase, and pruritus. There were no treatment-related deaths, and 11% discontinued therapy because of adverse events. Currently, a phase 3 study is comparing nivolumab vs. sorafenib as first-line therapy in advanced HCC and compensated liver disease (NCT02576509). Another phase 3 study is testing the efficacy of nivolumab vs. placebo in patients with HCC who are at high risk for recurrence after curative resection or ablation (NCT03383458).

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®; Merck & Co., Inc., USA) is another PD-1 antibody that was granted accelerated approval for second-line therapy of advanced HCC at the end of 2018 based on a phase 2, nonrandomized, open-label trial (KEYNOTE-224).42 This trial noted an objective response in 18 (17%) of the 104 enrolled patients with one complete response. TEAEs were similar to those of nivolumab. Immune-mediated events occurred in 14%, and 3% had immune-mediated hepatitis. In February 2019, the developer of pembrolizumab announced that pembrolizumab vs. placebo as second-line therapy did not meet the primary endpoints of improving OS and PFS in a large, multicenter, phase 3 trail (KEYNOTE-240) (NCT02702401). A similar phase 3 trial in the Asia-Pacific region is still enrolling patients (NCT3062358).

Practical recommendations based on current evidence

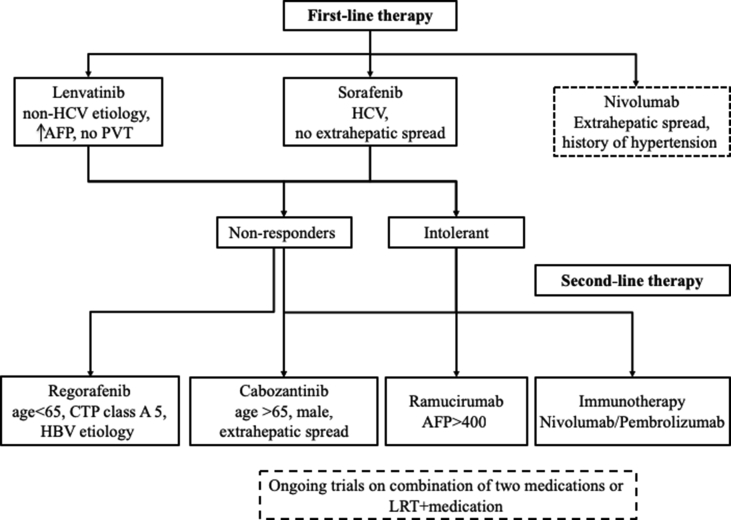

Sorafenib and lenvatinib are the current approved first-line therapies for advanced HCC. Sorafenib should be preferred in patients with HCV etiology and in those with preserved liver function with no extrahepatic spread. Lenvatinib might be beneficial as first-line treatment in patients with non-HCV etiologies, advanced HCC with no portal vein or biliary involvement, and elevated AFP. Rate of adverse events leading to discontinuation or dose reduction appears similar for both medications. An ongoing phase 3 clinical trial is comparing the efficacy of nivolumab vs. sorafenib (NCT02576509) as a first-line therapy. Another trial is comparing a combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab with lenvatinib (with placebo) as a first-line therapy (NCT03713593). Patients intolerant to sorafenib might benefit from immunotherapy or cabozantinib depending on the adverse event spectrum. In patients who fail first-line therapy, the options are regorafenib, cabozantinib, or immunotherapy. Ramucirumab could be an option for patients with elevated AFP. Ongoing trials of combination between TKI and immune checkpoint inhibitor and/or LRT have the potential to improve the armamentarium for the management of advanced HCC (Table 2). A possible treatment algorithm is summarized in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Ongoing Phase 3 Clinical Trials on Systemic Therapy of Advanced/Unresectable HCC.

| Study drug(s) | Control arm | Design and eligibility | Clinical trials identifier | Mechanisma | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab + best supportive care | Placebo + best supportive care | Second-line; Asian population; BCLC-B not eligible for LRT; BCLC-C; CTP A; ECOG ≤ 1 |

NCT03062358 | Anti–PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor | Recruiting |

| Lenvatinib + pembrolizumab | Lenvatinib + placebo | First-line; BCLC-B not eligible for LRT; BCLC-C; CTP A; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03713593 | Lenvatinib: TKI inhibits VEGFR and FGFR | Recruiting |

| Cabozantinib + atezolizumab | Sorafenib | First-line; not eligible for LRT; BCLC-B or C; CTP A; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03755791 | Cabozantinib: TKI inhibits VEGFR Atezolizumab: Anti–PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor |

Recruiting |

| Atezolizumab + bevacizumab | Sorafenib | First-line; locally advanced or metastatic HCC; CTP A; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03434379 | Bevacizumab: blocks angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGF-A | Recruiting |

| Durvalumab + tremelimumab or durvalumab alone | Sorafenib | First-line; BCLC-B not eligible for LRT; BCLC-C; CTP A; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03298451 | Durvalumab: Anti–PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor Tremelimumab: Anti–CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitor |

Recruiting |

| Durvalumab + bevacizumab Durvalumab + placebo |

Placebo + placebo | Successful resection or ablation of high-risk HCC; CTP 5 or 6; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03847428 | Recruiting | |

| TACE + durvalumab TACE + durvalumab + bevacizumab |

TACE + placebo | No extrahepatic disease; CTP A to B7; ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03778957 | Recruiting | |

| SHR-1210 + apatinib mesylate | Sorafenib | First-line; BCLC-B or C, not amenable or progressing after LRT; CTP A, ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03764293 | SHR-1210: anti–PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor Apatinib: VEGFR2 TKI |

Not yet recruiting |

| BGB-A317 | Sorafenib | First-line; BCLC-B or C, not amenable or progressing after LRT; CTP A, ECOG ≤ 1 | NCT03412773 | Anti–PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor | Recruiting |

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LRT, local-regional therapy; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PD-1, programmed cell death-1; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Mechanism of action of the study drugs that are part of different trials is explained only once in the first mentioned trial.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm based on currently approved medications for treatment of advanced HCC. Each box contains the subgroup of patients that would benefit the most from the medication. Boxes wrapped in dash lines represent medication or treatment options that have not been approved by the FDA yet, but there are ongoing clinical trials. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; LRT, local-regional therapy; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

Despite the advances in our understanding of the molecular alterations in HCC, there is lack of reliable biomarkers to predict the response to currently available medications. A timely consideration of systemic therapy is an important part of advanced HCC management. Stratification of patients at high risk for progression who would benefit from combination therapies is highly needed to improve cost-effectiveness and decrease treatment-related toxicities. A multidisciplinary management and close collaboration between hepatology, oncology, and interventional radiology centered over patients' goals for therapy is essential for optimal outcomes.

Authors' contributions

I.D. drafted the manuscript and approved the final submission. P.J.T. critically revised the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Liu Z., Jiang Y., Yuan H. The trends in incidence of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and implications for liver cancer prevention. J Hepatol. 2019;70:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertuccio P., Turati F., Carioli G. Global trends and predictions in hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. J Hepatol. 2017;67:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabibbo G., Enea M., Attanasio M. A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51:1274–1283. doi: 10.1002/hep.23485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Njei B., Rotman Y., Ditah I. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology. 2015;61:191–199. doi: 10.1002/hep.27388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z., Cole P.A. Catalytic mechanisms and regulation of protein kinases. Methods Enzymol. 2014;548:1–21. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397918-6.00001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regad T. Targeting RTK signaling pathways in cancer. Cancers. 2015;7:1758–1784. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiao Q., Bi L., Ren Y. Advances in studies of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and their acquired resistance. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0801-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribas A., Wolchok J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder E.I., Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postow M.A., Sidlow R., Hellmann M.D. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D.Y., Salem J.E., Cohen J.V. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1721–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L., Cao Y., Chen C. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11851–11858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilhelm S.M., Carter C., Tang L. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llovet J.M., Ricci S., Mazzaferro V. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng A.L., Kang Y.K., Chen Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrero J.A., Kudo M., Venook A.P. Observational registry of sorafenib use in clinical practice across Child-Pugh subgroups: the GIDEON study. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1140–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iavarone M., Cabibbo G., Piscaglia F. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology. 2011;54:2055–2063. doi: 10.1002/hep.24644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruix J., Cheng A.L., Meinhardt G. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang E., Xia D., Bai W. Hand-foot-skin reaction of grade >/= 2 within sixty days as the optimal clinical marker best help predict survival in sorafenib therapy for HCC. Investig New Drugs. 2019 Jun;37:401–414. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz-Gonzalez A., Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M., Sapena V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the critical role of dermatological events in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:482–491. doi: 10.1111/apt.15088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao E.H., Guo D., Bian D.J. Effect of preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization on angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4582–4586. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L., Zhao W., Wang M. Transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib for the management of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:138. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kudo M., Ueshima K., Torimura T. Randomized, open label, multicenter, phase II trial of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) therapy in combination with sorafenib as compared to TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(l) Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J.W., Kim Y.J., Kim D.Y. Sorafenib with or without concurrent transarterial chemoembolization in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the phase III STAH trial. J Hepatol. 2019;70:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricke J., Sangro B., Amthauer H. The impact of combining Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (SIRT) with Sorafenib on overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the Soramic trial palliative cohort. [Abstract] J Hepatol. 2018;68:S102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto Y., Matsui J., Matsushima T. Lenvatinib, an angiogenesis inhibitor targeting VEGFR/FGFR, shows broad antitumor activity in human tumor xenograft models associated with microvessel density and pericyte coverage. Vasc Cell. 2014;6:18. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura T., Kato Y., Ozawa Y. Immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib contributes to antitumor activity in the Hepa1-6 hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3993–4002. doi: 10.1111/cas.13806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo M., Finn R.S., Qin S. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilhelm S.M., Dumas J., Adnane L. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506): a new oral multikinase inhibitor of angiogenic, stromal and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases with potent preclinical antitumor activity. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:245–255. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruix J., Qin S., Merle P. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reig M., Rimola J., Torres F. Postprogression survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for second-line trial design. Hepatology. 2013;58:2023–2031. doi: 10.1002/hep.26586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finn R.S., Merle P., Granito A. Outcomes of sequential treatment with sorafenib followed by regorafenib for HCC: additional analyses from the phase III RESORCE trial. J Hepatol. 2018;69:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlomai A., Leshno M., Goldstein D.A. Regorafenib treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib-A cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207132. e0207132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teufel M., Seidel H., Kochert K. Biomarkers associated with response to regorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019 May;156:1731–1741. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yakes F.M., Chen J., Tan J. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2298–2308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang Q., Chen W., Ren M. Cabozantinib suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma by a dual blockade of VEGFR2 and MET. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2959–2970. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abou-Alfa G.K., Meyer T., Cheng A.L. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu A.X., Park J.O., Ryoo B.Y. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:859–870. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu A.X., Baron A.D., Malfertheiner P. Ramucirumab as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of REACH trial results by child-pugh score. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:235–243. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu A.X., Kang Y.K., Yen C.J. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Khoueiry A.B., Sangro B., Yau T. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu A.X., Finn R.S., Edeline J. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]