Abstract

Background/aim

: Portal hypertension and variceal hemorrhage (VH) are significant complications in biliary atresia (BA). The study aims to evaluate risk factors and noninvasive markers that predict actual VH for the first time in children with BA without prior endoscopic surveillance or treatment.

Methods

Retrospective review was performed of patients diagnosed with BA from 1989 to 2016 at a single center. Primary outcome was the first episode of VH. Patients were stratified into VH and non-VH groups according to the development of VH, and laboratory and ultrasonographic data were analyzed at 2 time points: pre-VH and the last follow-up. Existing indices, varices prediction rule (VPR), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)–platelet ratio index (APRI) were also applied retrospectively to evaluate their performance in prediction of VH in our cohort.

Results

Seventy-two patients were included; 16 patients developed the first VH at median age of 5.5 years. On univariate analysis, serum albumin (P = 0.034), AST (P = 0.017), hemoglobin (P = 0.019), platelet count (P = <0.001), spleen size Z-score (P = <0.001), and rate of splenic enlargement (P = 0.006) were associated with VH. On multivariable regression analysis, only platelet count was independently predictive (P = 0.041). The optimal cutoff values for prediction of the first VH were platelet count ≤100 × 109/L (sensitivity 75.0%, specificity 80.4%, positive predictive value [PPV] 52.2%, negative predictive value [NPV] 91.8%), VPR ≤3.0 (sensitivity 81.3%, specificity 85.7%, PPV 61.9%, NPV 94.1%), and APRI ≥3.0 (sensitivity 81.3%, specificity 76.8%, PPV 50.0%, NPV 93.5%).

Conclusions

Platelet count <100 × 109/L and VPR <3.0 are simple, reproducible and effective noninvasive markers in predicting the first episode of acute VH in children with BA and may be used in pediatrics for the selection of patients to undergo primary prophylactic endoscopic therapy.

Keywords: esophageal varices, portal hypertension, liver cirrhosis, hypersplenism, pediatrics

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase-platelet ratio index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AUROC, area under receiver operating characteristic curve; BA, biliary atresia; EV, esophageal varices; KP, Kasai portoenterostomy; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; VH, variceal hemorrhage; VPR, varices prediction rule

Biliary atresia (BA) is a fibro-obliterative disorder affecting extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts with onset in early infancy. Although a timely Kasai portoenterostomy (KP) may reestablish bile flow and alleviate biliary obstruction, with the main aim of preserving the function of the native liver, progressive biliary fibrosis and eventual cirrhosis still occur in the majority of patients.1 Portal hypertension has been reported to develop early in life in BA,2, 3 and variceal hemorrhage occurs in 17–29% in children with BA.4, 5 Moreover, the age of onset of VH in children with BA tends to be younger than that of other conditions.6, 7, 8 Mortality associated with VH has been reported between 15% and 50%, depending on other comorbidities.4, 5 As such, there is a need for effective surveillance strategies to monitor this group of young patients to identify the ones who are most at risk of VH. Endoscopic variceal ligation is an effective treatment for bleeding esophageal varices (EVs); however, unlike in the adult population, primary endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic treatment in pediatrics remain controversial and not universally adopted by all centers.9 Predictive scores and indices using noninvasive markers have been shown to correlate with the presence of significant EV on endoscopy in patients with portal hypertension from various etiologies including BA.10, 11, 12 However, some of these indices require specialized radiologic measurements and complex, multistep mathematical calculations that can limit usability and generalizability in the clinical setting.

The aim of this study is to evaluate early risk factors and examine laboratory markers and radiologic features that may predict actual VH for the first time in children with BA without prior endoscopic surveillance at a single tertiary center.

Methods

A retrospective review of medical and endoscopic records of patients diagnosed with BA from 1989 to 2016 was performed at KK Women's and Children's Hospital, which is the largest pediatric and neonatal facility in Singapore. Patients with splenic malformations and those who did not undergo KP were excluded from the study. Cases were identified from the department database. The diagnosis of BA was suspected based on findings of acholic stools and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in a young infant and confirmed by liver histology and operative cholangiogram at the time of KP. Patients were followed up at the unit's outpatient liver clinic every 1–6 months depending on the clinical condition, and each assessment would comprise clinical examination and blood investigations. Ultrasonographic scan of the hepatobiliary system, including measurement of spleen size, was performed once a year, or more frequently as indicated. VH was confirmed on endoscopy with the findings of significant EV after an episode of upper gastrointestinal bleed. During the study period, none of the BA patients had undergone primary endoscopic surveillance or prophylactic therapy.

Primary outcome measure was the first episode of acute VH, and patients were stratified into those who developed VH (VH group) and those who did not develop VH (non-VH group). Data collection included patient demographics, age at KP, jaundice clearance at 6 and 12 months, and cholangitis episodes within the first year after KP. Liver biochemistry, hematologic indices, and ultrasonographic data were collected and analyzed at 2 time points: ‘pre-VH’, which is defined as within 6 months before the first episode of acute VH, where median values were obtained if more than one result of the test were available, and at the last follow-up review. The purpose of obtaining median values over the 6-month time period was to minimize the influence of spurious or transient readings or effects on the results from treatment such as albumin infusion or blood product transfusion. Univariate analysis of the following markers at pre-VH for the VH group and at the last follow-up for the non-VH group was performed to examine for associations with the first episode of acute VH: serum albumin, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyltransferase, platelet count, hemoglobin, spleen size Z-score, and rate of splenic enlargement per year (cm/year). Spleen size was taken from the maximal dimension from inferolateral tip to the superior-medial border of the spleen on ultrasonography performed by a trained ultrasonographer and verified by a specialist pediatric radiologist, and the Z-score was based on reference values for normal spleen size based on age.13 Variables with significant association were then included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine independent predictive markers.

We have also chosen 2 indices that were previously published to be retrospectively tested on our cohort: the AST–platelet ratio index (APRI = [AST/upper limit of normal]/platelet count (× 109/L))14 and the varices prediction rule (VPR = [albumin (g/dL) × platelet count (× 109/L)]/1000).12 These prediction indices were chosen on the basis of ease of calculation and reproducibility.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Continuous variables were expressed as median (range or 25–75% interquartile range), whereas categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage). Comparisons between groups were performed using Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) analysis was used for the parameter(s) that significantly correlated with the risk of developing the first episode of VH, and the cutoff values were determined based on optimal sensitivity and specificity. Statistical significance was set at P value < 0.05.

Ethics approval for the study has been obtained from SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB reference number: 2008/932/E).

Results

Seventy-two of 76 patients diagnosed with BA during the study period were included in the study; 2 patients who did not undergo KP but proceeded to have primary liver transplantation and 2 patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded. Median follow-up period was 7 years (range: 0.5–29). None of our patients had congenital splenic malformations. Patient demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Disease Characteristics of 72 Patients With Biliary Atresia.

| Characteristics | Data (N = 72) |

|---|---|

| Male gender | 35 (48.6%) |

| Median age at KP (days) | 54 (29–119) |

| Jaundice clearance at 6 months | 40 (55.6%) |

| Median follow-up period (years) | 7 (0.5–29) |

| Patients who developed VH | 16 (22.2%) |

| Patients with recurrent (≥2 episodes) VH | 4 (5.6%) |

| Median age at first episode of acute VH (years) | 5.5 (0.3–19) |

Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage) and continuous variables as median (range).

KP, Kasai portoenterostomy; VH, variceal hemorrhage.

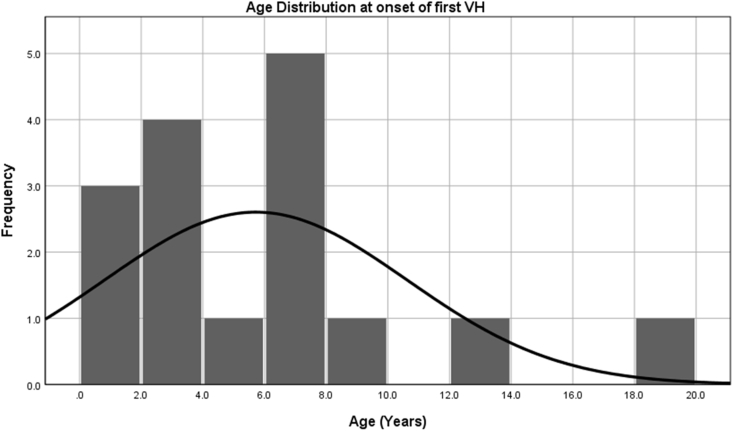

A total of 26 episodes of VH occurred in 16 patients, with overall incidence of 22% in our cohort and incidence rate of 3.5/100 patients per year of native liver survival. Median age at the first episode of acute VH was 5.5 years (range: 0.3–19). Age distribution is depicted in Figure 1. No significant association was found between early post-KP factors and future development of VH in our cohort. Although lower jaundice clearance rates post-KP at 6 months (37.5% vs 60.7%) and 12 months (40.0% vs 64.3%) were observed in the VH group as compared with the non-VH group, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of patients with biliary atresia at the onset of their first episode of acute variceal hemorrhage.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis Comparing Early Risk Factors and Noninvasive Markers Between Variceal Hemorrhage (VH) and Non-VH Groups.

| Early risk factors | VH (N = 16) | No VH (N = 56) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KP after 60 days | 7 (43.8%) | 18 (32.1%) | 0.741 |

| Jaundice clearance at 6 months | 6 (37.5%) | 34 (60.7%) | 0.102 |

| Jaundice clearance at 12 monthsa, | 6 (40.0%) | 36 (64.3%) | 0.091 |

| History of cholangitis (before VH) | 10 (62.5%) | 38 (69.1%) | 0.620 |

| Noninvasive markers | |||

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 28.0 (20–40) | 35.5 (16–45) | 0.034 |

| Serum bilirubin (umol/L) | 57.5 (9–825) | 25.0 (3–572) | 0.065 |

| Serum ALT (U/L) | 103.0 (40–269) | 62.5 (14–334) | 0.134 |

| Serum AST (U/L) | 148.0 (41–461) | 71.5 (22–492) | 0.017 |

| Serum GGT (U/L) | 216.0 (33–507) | 100.0 (16–2117) | 0.156 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.1 (8.2–12.9) | 11.9 (8.2–16.0) | 0.019 |

| Platelet count, x109/L | 83.5 (30–265) | 188.0 (21–467) | <0.001 |

| Spleen size Z score | 8.44 (0.13–19.89) | 2.27 (−2.05–12.13) | <0.001 |

| Increase in spleen size per year (cm) | 1.5 (0–5.1) | 0.6 (0–4.7) | 0.006 |

Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage), and continuous variables as median (range).

KP, Kasai portoenterostomy; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase.

Data available in 71 patients.

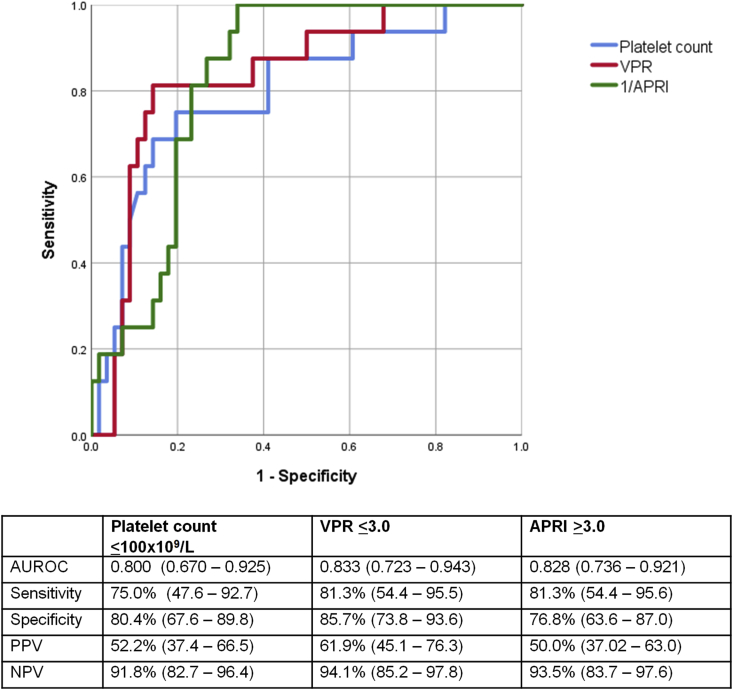

Univariate analysis of biochemical and ultrasonographic parameters showed significant association between serum albumin, AST, hemoglobin, platelet count, spleen length Z-score, and rate of splenic enlargement per year with the development of VH (Table 2). With the inclusion of these variables in a multivariable logistic regression model, serum platelet count was the only independent variable which retained statistical significance in predicting the first episode of VH after adjustment for confounders (P = 0.041). ROC curves were generated for serum platelets and the other existing indices, APRI and VPR, in the prediction of acute VH, and these are illustrated in Figure 2. AUROC for serum platelet count in predicting the first episode of VH was 0.80 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.67–0.93, P = <0.001). In comparison, retrospective application of APRI and VPR in our cohort yielded AUROC of 0.83 (95 CI: 0.74–0.92, P = <0.001) and 0.83 (95 CI: 0.72–0.94, P = <0.001), respectively. Cutoff values of ≤100 × 109/L for serum platelet count, ≤3.0 for VPR, and ≥3.0 for APRI were determined based on optimal sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs), and negative predictive values (NPVs), which are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for platelet count (blue); varices prediction rule (VPR) (red); AST–platelet ratio index (APRI) (green); and summary of area under ROC (AUROC), sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) in predicting the first episode of acute variceal hemorrhage in children with biliary atresia. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

When the cutoff of VPR ≤7.2, as proposed in an article by Isted et al12 for the prediction of significant EV, was applied to our study cohort, this yielded sensitivity of 94.8%, specificity of 37.5%, PPV of 30.0%, and NPV of 95.5%.

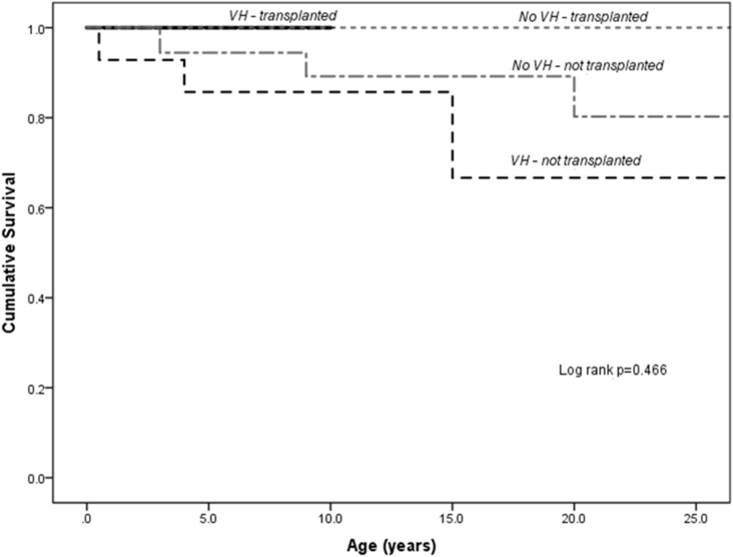

Analyzing the long-term outcomes of the entire BA cohort, 18 patients (23.7%) underwent liver transplantation at median age of 2 years (range: 1–27) and 8 patients (11%) died during the study period. Five-year native liver survival and 5-year overall survival rates after the first VH were 67% and 80%, respectively. Patients in the VH group were more likely to be associated with mortality from any cause (25% vs 7%, P = 0.045); median interval from first episode of VH to time of death was 1.5 years (range: 0.2–8 years). With liver transplantation, long-term survival was comparable between the VH group and non-VH group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients with biliary atresia after Kasai portoenterostomy, stratified according to development of variceal hemorrhage (VH) and liver transplantation status. Liver transplantation offers improved survival in patients who had developed VH.

Discussion

Our data suggest that serum platelet count as a single marker best predicts the risk of imminent VH in BA patients without prior history of VH or endoscopic surveillance. Based on our results, platelet count ≤100 × 109/L is not significantly inferior to VPR and APRI in its performance as a quick and simple screening tool in clinical practice for the prediction of VH and selection of patients for primary prophylactic endoscopic therapy. VPR, proposed by Isted et al,12 takes into account platelet count and serum albumin levels in its calculation, and it provided the best AUROC, PPV, and NPV performance, in comparison to platelet count alone and APRI, when retrospectively applied to our cohort using a lower cutoff of ≤3.0 to predict the first episode of VH rather than nonbleeding EV on endoscopy.

While our study adds to the growing data on noninvasive markers for EV in chronic liver disease, most of the recent pediatric studies used significant EV, defined as grade II or III EV based on classification by the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension15 detected on routine or surveillance endoscopy as an end point in patients with no history of VH. As primary endoscopic surveillance was not part of the management protocol at our unit, we could use actual acute VH events in patients with no prior endoscopic surveillance or therapy as the primary outcome measure. Hence, the strength of our study is the ability to explore the correlation between noninvasive markers and the actual risk of the first episode of acute VH in BA. At the time of writing, data on predictive indices for actual VH rather than endoscopic detection of EV are scarce. Our study is also confined to a homogenous population of patients with BA, as this represents the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children and we recognize this unique group of patients to be of significant risk of VH at an early age.

Other investigators have reported the use of platelet count as a noninvasive marker for portal hypertension and EV in the adult population. Ng et al16 suggested that platelet count <150 × 109/L predicts high-grade varices with an odds ratio (OR) of 6.63 (95% CI: 1.43–30.80), and together with the presence of ascites, the PPV and NPV for high-grade varices were 35% and 100%, respectively. Schepis et al17 reported that a cutoff for platelet count of 100 × 109/L provided an OR of 2.92 (95% CI: 1.3–6.4) in predicting the presence of EV. Other authors have proposed lower cutoff values: Zaman et al18 used platelet count ≤80 × 109/L for predicting large EV and published an OR of 2.3 (95% CI: 1.4–3.9) with sensitivity and specificity of 62.4% and 67.6%, respectively; Madhotra et al19 published sensitivity and specificity of 71% and 73%, respectively, for a platelet cutoff of 68 × 109/L. In pediatrics, recent studies using platelet counts yielded AUROC of 0.79—0.82 which is comparable with our study, and a platelet cutoff of ≤115 × 109/L provided PPV and NPV of 86% and 63%, respectively.10, 11 In contrast, Fagundes et al20 reported that although platelet count ≤ 120 × 109/L was more prevalent in cirrhotic children with EV, only splenomegaly and hypoalbuminemia were independent predictors for EV. The inconsistent results in these published data, in addition to our study, are largely due to differences in age group, heterogeneity in liver disease etiologies with varying prevalence of EV/VH, and different outcome measures that consisted of nonbleeding EV, high-grade EV, or actual VH.

Composite indices combining more than one biochemical or radiologic parameter to predict EV have also been formulated and investigated extensively. Platelet/spleen diameter ratio was investigated by Giannini et al21, and the authors concluded that a cutoff of 909 provided PPV of 74% and NPV of 100% in predicting presence of EV, with improvement of AUROC from 0.880 to 0.921 when compared with using platelet count alone. However, the limitation in pediatrics with this method is that normal ranges for spleen size vary with age. Spleen size Z-score has been shown to be associated with the presence of EV in children.10, 11 The clinical prediction rule proposed by Gana et al10 takes into account platelet count, spleen size Z-score, and serum albumin in its calculation, which gives an AUROC of 0.80, with PPV of 87% and NPV of 64% using a cutoff value of 116. The King's Variceal Prediction Score reported by Witters et al22 is calculated based on serum albumin and ‘equivalent adult spleen size’, which provides an AUROC of 0.77–0.82 and PPV and NPV of 82% and 60%, respectively, when a cut-off of 76 is applied. Both of these scoring systems involve multiple mathematical steps and also require the measurement of spleen size which may be subject to potential interoperator variability. Furthermore, although our data has shown that the rate of splenic enlargement per year was significantly greater in the VH group, we acknowledge that the relatively narrow difference (1.5 vs 0.6 cm/year), wide CIs, and associated interoperator variability make this finding less clinically applicable. Hence, in our study, we decided to focus on indices that can be conveniently and reproducibly obtained in the busy clinical setting.

APRI was proposed by Wai et al14 as a noninvasive index for predicting cirrhosis and fibrosis in hepatitis C patients, and there has been interest in applying APRI in prognosticating infants with BA 23, 24. Pediatric studies reporting the performance of APRI as a predictor for EV have proposed cutoff values ranging from 0.96 to 1.64, with PPV and NPV of 40–87.5% and 86–87%, respectively.12, 25 In our study, using actual acute VH as the primary outcome yielded a higher cutoff for APRI at >3.0, with a more favorable NPV of 93%. The best performing index in our study was VPR, which was proposed by Isted et al. In their study, a cutoff of ≤7.2 at the time point of 6 months post-KP was shown to be predictive of future development of significant EV, defined by grade II or III EV on surveillance endoscopy or actual VH, providing PPV and NPV of 45% and 95% (AUROC 0.75, 95% CI 0.66–0.84), respectively. By applying VPR linearly at successive stages of follow-up and using acute VH within 6 months as our outcome measure, we found that VPR provided a superior AUROC profile (0.83), and the lower VPR cutoff of ≤3.0 yielded an improved PPV of 62%, while maintaining a comparable NPV of 94%.

Comparing our findings with those that have been previously published, using more stringent cutoff values for these noninvasive indices in predicting acute VH rather than nonbleeding EV appears to enhance their diagnostic performance, with better AUROC, PPV, and NPV profiles. This has significant implication in developing clinical criteria for selecting patients at increased risk of VH for primary endoscopic surveillance, as a more targeted screening strategy not only reduces the burden of repeated procedures for patients who might be of lesser risk of VH but also reduces the strain on health-care resources and results in improved cost-effectiveness.17, 21 Acute endoscopic treatment and the role of secondary prophylactic therapy for EV in pediatrics have been well established; however, primary endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic therapy in children remain controversial.9 The scarcity of evidence in predicting VH based on endoscopic appearance of EV, reluctance to subject young children to repeated endoscopies under anesthesia, and the difficulty in passing banding devices in smaller patients are some of the obstacles that explain why primary endoscopic surveillance has not been universally adopted by all centers. Studies on primary endoscopic surveillance in children with BA have shown that varices are prevalent and develop at an early age in this subgroup of patients. Lampela et al26 published data from primary endoscopic screening starting since the median age of 9 months, and they reported that significant EV (grade II or III) developed with similar frequency in patients who had successful KP (53%) and those who had failed KP (64%), and EV developed at a very early stage at the median age of 1.5 (range of 0.5–13.8) years. Similarly, Duche et al27 found that majority (74 of 88) of patients with BA who had EV detected at the first endoscopic screening were younger than 2 years. As demonstrated in our study as well as others, VH remains a major risk in children with BA associated with significant morbidity and mortality.4, 5 Therefore, the rationale for primary endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic intervention is to avoid the morbidity associated with the first VH. Ideally to ensure cost-effectiveness of this strategy, only patients most at risk of VH should undergo endoscopic screening and prophylactic treatment.

Based on this study that examines actual first episodes of VH as the primary outcome, we propose that VPR ≤3.0 and platelet count ≤100 × 109/L may be effective screening criteria for selection of children with BA to undergo primary endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic therapy. These biochemical markers are not applicable to BA patients with splenic malformations; however, noninvasive radiologic tools such as liver elastography may be useful for this specific subset of patients and should warrant further evaluation.

As we acknowledge the limitation of the retrospective method of data collection and its associated bias, the high follow-up rate in our cohort ensured consistency and comprehensiveness in the data collected over the study period. Based on our findings, our unit has since adopted the proposed criteria of VPR ≤3.0 and/or platelet count ≤100 × 109/L on at least 2 separate measurements at least 1 month apart at any point post-KP for offering prophylactic endoscopic treatment for patients with BA. Future prospective data will be ideal to further investigate these noninvasive markers in other causes of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension in pediatrics as well.

Conclusion

Platelet count ≤100 × 109/L and VPR ≤3.0 are effective noninvasive markers in predicting the first episode of acute VH in children with BA. We propose that these markers can be used as simple, easily reproducible screening criteria for selection of patients to undergo primary endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic therapy for EV.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Hartley J.L., Davenport M., Kelly D.A. Biliary atresia. Lancet. 2009;374:1704–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60946-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shalaby A., Makin E., Davenport M. Portal venous pressure in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shneider B.L., Abel B., Haber B. Portal hypertension in children and young adults with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:567–573. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826eb0cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Heurn L.W., Saing H., Tam P.K. Portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: long-term survival and prognosis after esophageal variceal bleeding. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miga D., Sokol R.J., MacKenzie T., Narkewicz M.R., Smith D., Karrer F.M. Survival after first esophageal variceal hemorrhage in patients with biliary atresia. J Pediatr. 2001;139:291–296. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKiernan P., Abdel-Hady M. Advances in the management of childhood portal hypertension. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(5):575–583. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.993610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiou F.K., Abdel-Hady M. Portal hypertension in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;27:540–545. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanty C., Helleputte T., Smets F., Sokal E.M., Stephenne X. Assessment of risk of bleeding from esophageal varices during management of biliary atresia in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:537–543. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318282a22c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider B.L., Bosch J., de Franchis R. Portal hypertension in children: expert pediatric opinion on the report of the Baveno V Consensus Workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:426–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gana J.C., Turner D., Mieli-Vergani G. A clinical prediction rule and platelet count predict esophageal varices in children. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2009–2016. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adami M.R., Ferreira C.T., Kieling C.O., Hirakata V., Vieira S.M.G. Noninvasive methods for prediction of esophageal varices in pediatric patients with portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2053–2059. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isted A., Grammatikopoulos T., Davenport M. Prediction of esophageal varices in biliary atresia: derivation of the “varices prediction rule”, a novel noninvasive predictor. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1734–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Megremis S.D., Vlachonikolis I.G., Tsilimigaki A.M. Spleen length in childhood with US: normal values based on age, sex, and somatometric parameters. Radiology. 2004;231:129–134. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2311020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wai C.T., Greenson J.K., Fontana R.J. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beppu K., Inokuchi K., Koyanagi N. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(81)73224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng F.H., Wong S.Y., Loo C.K., Lam K.M., Lai C.W., Cheng C.S. Prediction of oesophagogastric varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:785–790. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schepis F., Camma C., Niceforo D. Which patients with cirrhosis should undergo endoscopic screening for esophageal varices detection? Hepatology. 2001;33:333–338. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaman A., Becker T., Lopidus J., Benner K. Risk factors for the presence of varices in cirrhotic patients without a history of variceal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2564–2570. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhotra R., Mulcahy H.E., Willner I., Reuben A. Prediction of esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:81–85. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fugundes E.D.T., Ferreira A.R., Roquete M.L.V. Clinical and laboratory predictors of esophageal varices in children and adolescents with portal hypertension syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:178–183. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318156ff07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giannini E., Botta F., Borro P. Platelet count/spleen diameter ratio: proposal and validation of a non-invasive parameter to predict the presence of oesophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gut. 2003;52:1200–1205. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.8.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witters P., Hughes D., Karthikeyan P. King's variceal prediction score: a novel noninvasive marker of portal hypertension in pediatric chronic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:518–523. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grieve A., Makin E., Davenport M. Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRi) in infants with biliary atresia: prognostic value at presentation. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L.Y., Peng X.F., Pang S.Y. Validation of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio for diagnosis of liver fibrosis and prediction of postoperative prognosis in infants with biliary atresia. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5893–5900. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colecchia A., Di Biase A.R., Scaioli E. Non-invasive methods can predict oesophageal varices in patients with biliary atresia after a Kasai procedure. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:659–663. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lampela H., Kosola S., Koivusalo A. Endoscopic surveillance and primary prophylaxis sclerotherapy of esophageal varices in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:574–579. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825f53e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duche M., Ducot B., Tournay E. Prognostic value of endoscopy in children with biliary atresia at risk for early development of varices and bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1952–1960. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]