Highlights

-

•

Physical therapists routinely examine strength, range of motion and muscle flexibility of the hip(s) for individuals with low back pain.

-

•

Physical therapists often provide strengthening and flexibility interventions targeting the hips for individuals with low back pain.

-

•

Post-professional fellowship training as a physical therapist changed intervention selection to include more joint manual therapy and less muscle flexibility and modality usage.

Keywords: Hip, Low back, Practice pattern, Survey

Abstract

Objectives

The main research aims were to investigate whether physical therapists are examining the hip(s) in individuals with a primary complaint of low back pain (LBP) and if so, the interventions being provided that target the hip(s).

Methods

An anonymous electronic survey was distributed to the membership of the American Physical Therapy Association Orthopaedic and Sports Sections, as well as that of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists. Participant demographics and survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Associations between variables were examined using chi-square analysis.

Results

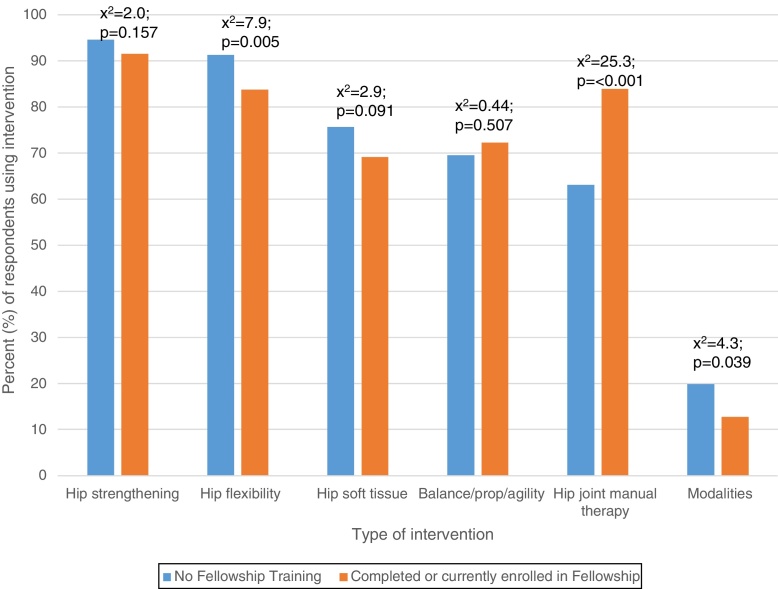

The estimated response rate was 18.4% (n = 1163, mean age 40.5 ± 11.4 years). The majority of respondents (91%, n = 1059) reported they always or most of the time examined the hip(s) in individuals with LBP. The most common examination items utilized were hip strength testing (94%, n = 948), passive range of motion (91%, n = 921) and muscle flexibility testing (90%, n = 906). The most common interventions included hip strengthening (94%, n = 866) and hip flexibility exercises (90%, n = 814). Respondents enrolled in or having completed a post-professional fellowship were more likely to utilize hip joint manual therapy techniques (x2 = 25.3, p = <0.001) and less likely to prescribe hip flexibility exercises (x2 = 7.9, p = 0.005) or use electrophysical modalities (x2 = 4.3, p = 0.039).

Conclusions

Physical therapists commonly examine and provide interventions directed at the hip(s) for individuals with LBP. Post-professional fellowship training appears to influence the intervention selection of the physical therapist, with an increase in usage of hip joint manual therapy and a decrease in hip muscle flexibility and modality usage.

Introduction

Current physical therapy clinical practice guidelines recommend a thorough examination and various types of interventions for individuals with a primary complaint of low back pain (LBP).1, 2 There is not yet a consensus among LBP guidelines, but this particular guideline discusses the role of the hip and recommend that clinicians examine and provide interventions directed at the hip(s) for individuals with LBP.1 There is increasing evidence that individuals with LBP may have physical impairments at the hips.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Deficits in range of motion (ROM) and/or strength of one or both hips seem to be commonly reported impairments for individuals with LBP.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Altered ROM of the hip joint has been identified in individuals with LBP in several studies, although no clear pattern as to the direction(s) of ROM limitation(s) has emerged. In a systematic review, Redmond et al. pooled data regarding hip ROM limitations in individuals with LBP and found decreases in the directions of internal rotation, total rotation and flexion were the most commonly reported.12 In a recent study of 101 consecutive patients with LBP, patients with reduced ROM of the hips reported that they had significantly higher ratings of perceived disability.13 Taken together these findings suggest hip ROM deficits are commonly observed in individuals with LBP conditions and may impact the individual's perception of disability.

In addition to the findings of hip ROM deficits, there are also reports of altered strength of the hip and gluteal musculature in individuals with LBP. Reduced hip abduction torque in patients with LBP has been consistently demonstrated in the literature.4, 5, 6 With emerging evidence that hip impairments are present in individuals with LBP, it is arguable that the hip(s) should be examined in these patients.3, 14 It is unclear however whether physical therapists, who often assess individual joints or body regions, are examining the hip(s) for impairments in individuals with LBP.

Recently a number of studies have examined the efficacy of providing interventions targeting hip impairments in individuals with LBP.3, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Three studies have investigated the effects of providing interventions aimed at the hips for these individuals, but the results have been mixed indicating no clear association between providing interventions at the hips and improved outcomes for LBP.16, 17, 18 In these studies, a single type of intervention (e.g., strengthening, motor control) was used, which is likely not representative of typical clinical practice and limits the generalizability of the results to clinical practice. In a recent randomized clinical trial, Bade et al. reported that pragmatic physical therapy interventions directed at the lumbar spine, plus a prescriptive set of manual therapy and exercise interventions directed at the hips, resulted in improved pain and disability when compared to treating the lumbar spine only.19 This study provides some evidence supporting interventions targeting the hip in individuals with LBP, however it is unknown whether this approach is actually utilized in clinical practice.

Despite the growing evidence for the assessment and treatment of the hip in individuals with LBP, little is known regarding the practice patterns of physical therapists in terms of whether they consider the hip in their assessment and treatment of a patient with LBP. Thus the purpose of this study was to identify the current practice patterns of physical therapists in the United States pertaining to their examination and treatment of the hip(s) in individuals with a primary complaint of LBP. Additionally, we aimed to identify the most commonly used assessment techniques and interventions aimed at the hip(s) for individuals with LBP currently employed by physical therapists. We hypothesize that physical therapists in the US frequently perform assessment techniques of the hip(s) for individuals with LBP and provide a variety of interventions targeting those impairments.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional observational survey approved by the Temple University, Institutional Review Board (Protocol #23865), Philadelphia, PA, USA, and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2016-0077), Callaghan, NSW, Australia.

Participants

We surveyed physical therapists from January to July 2017 who were members of the Orthopaedic and Sports Sections of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and/or the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT). There were approximately 10,000 physical therapists that are members of the Orthopaedic and Sports sections of APTA and 2000 members of AAOMPT. We specifically targeted these groups for recruitment as they were likely to comprise physical therapists who regularly treat musculoskeletal conditions including LBP. The survey was conducted electronically using Qualtrics® (Provo, UT), which is a web-based application designed to conduct research surveys. The link to the survey was distributed via electronic newsletters or targeted emails, and reminders were sent if an individual group agreed to this. Eligible participants were physical therapists who received the survey link. An eligible participant would click on the electronic link, review a consent document that include investigator contact information and then would click a button to proceed to the actual survey questions.

Survey design

The survey was initially developed by the research team following consultation with the published literature. Two independent content experts then reviewed the study tool for content and construct validity. The content experts were both physical therapists, educators and researchers in the area of LBP and the hip. The survey then underwent pilot testing with six physical therapists representative of the survey group. Following both the content expert review and the pilot testing, the research team modified the survey instrument to improve clarity and content.

The survey comprised 55 open and closed-ended questions regarding the participant's practice patterns specific to the examination and treatment of the hip(s) in individuals with LBP, along with demographic items. The survey therefore included three sections: (1) examination, (2) intervention and (3) demographics. The examination section included 15 questions about the components of the patient history that would lead the physical therapist to examine the hip(s). These included age, duration of symptoms, patient reported symptoms and outcomes, and medical/chart review information. For example, respondents were asked how a physician referral may affect their decision to examine the hip(s). The examination section also investigated the frequency that physical therapists performed various components of the hip physical examination in individuals with LBP (i.e., muscle flexibility, strength, ROM, joint and soft tissue mobility). Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale (Always, Most of the Time, Sometimes, Rarely, Never) to indicate the likelihood they would include that examination component in their assessment of the hip for individuals with LBP. If a participant responded with an answer of ‘Always, Most of the Time or Sometimes’ they would then be directed to specific questions related to that domain. For example, if a respondent indicated that they always included muscle length and flexibility testing of the hip, then they would be directed to questions regarding the particular muscles usually included in their length/flexibility assessment.

The intervention section included 25 questions asking participants if they provided interventions targeting the hip(s) in individuals with a primary complaint of LBP. The interventions were categorized into exercise, manual therapy techniques and electrophysical modalities. The exercise section included items pertaining to hip strengthening, hip stretching/flexibility, dynamic training, balance, proprioception and other interventions. The manual therapy section was divided into joint-related and soft tissue-related techniques. The modalities section included commonly utilized modalities in clinical practice, such as thermal agents and electrical stimulation devices. The demographic section of the survey included 15 questions related to the demographics, clinical practice and education characteristics of the respondent.

Data analysis

The survey raw data was downloaded from Qualtrics® (Provo, UT) and exported to IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic data including sex, age group, region of residence, number of years in practice, type of entry-level degree and any advanced certifications/specializations. Proportions of individuals are reported for responses to each item in the survey. Relationships between survey responses for assessment and intervention techniques and participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, post-professional education) were explored using Chi-square analyses (α = 0.05).

Results

Survey response

As our survey was anonymous and distributed to approximately 21,000 email addresses, in order to estimate the response rate we obtained the email opening rates for our survey. Opening rate is the percentage of individuals that opened the email that contained the link to the survey. We were able to obtain email open rate data for the Sports Section, however the other two distributions (Orthopaedic Section and AAOMPT newsletter) were unable to provide these data. The Sports Section email distribution had an average email open rate of 28.7%. Using an estimated open rate of 30% across all groups, we determined there were approximately 6300 individuals who opened the email and thus could be considered as receiving the survey. From that estimated total, the response rate is approximately 18.4%, as 1163 individuals consented and participated in the study.

Survey respondents did not have to answer every question. The respondents were routed to particular questions based on their responses to previous questions. For instance, if a respondent reported that they ‘never’ performed a particular intervention directed at the hip(s), then they would have been routed to skip the section with further questions regarding that specific intervention. Therefore, the number of respondents (n) reported for each question varies. The average time to complete the survey was 19 min.

Participant demographics

The demographic section was at the end of the survey and not all respondents completed this section. The characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Respondents (n = 896; 50% female, n = 448; mean age 40.5 years ± 11.4, range 23–83) had been practicing as physical therapists for a mean (SD) of 14.6 (±11.6) years (range 0–55). Eighty-five percent of respondents worked in a private or hospital-based outpatient clinic. Respondents reported providing direct patient care for an average of 33.1 (±12.5) hours per week (range 0–90). During their clinical hours, approximately 40.7% (±18.4%, range 0–100%) of their caseload was treating individuals with a primary complaint of LBP (range 0–100). Approximately 68% of all respondents reported they had a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) degree, 51% had Orthopaedic Clinical Specialist (OCS) designation and 18% were currently enrolled in or had completed post-professional fellowship training.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents.a

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | n = 896 |

| Male | 447 (49.9) |

| Female | 448 (50.0) |

| Indeterminate | 1 (0.1) |

| Region of residence | n = 893 |

| South Atlantic (DE, MD, DC, GA, NC, PR, SC, VA, WV, FL) | 163 (18.3) |

| Middle Atlantic (NJ, NY, PA) | 161 (18.0) |

| East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI) | 135 (15.1) |

| West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, ND, SD) | 77 (8.6) |

| East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN) | 27 (3.0) |

| West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX) | 46 (5.2) |

| New England (CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) | 41 (4.6) |

| Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA) | 150 (16.8) |

| Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY) | 93 (10.4) |

| Primary facility or setting type | n = 894 |

| Acute care hospital | 8 (0.9) |

| Health system or hospital-based outpatient clinic | 318 (35.6) |

| Private outpatient practice or group practice | 478 (53.5) |

| Skilled nursing facility/extended or intermediate care facility | 4 (0.4) |

| School system (preschool, primary, secondary) | 2 (0.2) |

| Academic institution (post-secondary) | 64 (7.2) |

| Health and wellness facility | 10 (1.1) |

| Research centre | 1(0.1) |

| Industry | 9 (1.0) |

| Entry-level degree | n = 895 |

| Certificate | 21 (2.3) |

| Bachelors | 176 (19.7) |

| Masters | 229 (25.6) |

| Doctoral | 469 (52.4) |

| Highest degree obtained | n = 885 |

| Certificate | 6 (0.7) |

| Bachelors | 67 (7.6) |

| Masters | 123 (13.9) |

| Doctoral (DPT) | 598 (67.6) |

| Doctoral (DSc, PhD, EdD) | 81 (10.3) |

| American Board of Physical Therapy Specialist (ABPTS) certification | n = 891 |

| Yes | 452 (50.7) |

| No | 439 (49.3) |

| If yes, which specialization | |

| Orthopaedics | 387 |

| Sports | 100 |

| Faculty | 5 |

| Paediatrics | 3 |

| Women's Health | 2 |

| Neurology | 0 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0 |

| Acute Care | 0 |

| Wound Care | 0 |

| Fellowship trained or currently enrolled | n = 894 |

| Yes | 159 (17.8) |

| No | 735 (82.2) |

| If yes, what type of fellowship | Current vs Complete |

| Orthopaedic manual physical therapy | 44 + 80 |

| Sports | 26 + 7 |

| Spine | 4 + 5 |

| Education leadership | 1 + 4 |

| Movement science | 1 + 2 |

| Upper extremity athlete | 0 + 1 |

| Critical care | 0 |

| Hand therapy | 0 |

| Neonatology | 0 |

| Mean (± SD) | |

| Age | 40.5 years (±11.4) |

| Years of practice as a physical therapist | 14.6 years (±11.6) |

| Number of hours in patient care per week | 33.1 hours (±12.5) |

| Percentage of caseload comprised of patients with low back pain | 40.7% (± 18.4) |

The total number of respondents that answered each question is variable because some respondents did not answer every question.

Clinical examination

The majority of participants (91%, n = 1059) responded that they ‘always or most of the time’ examine the hip(s) in individuals with a primary complaint of LBP. Respondents were further asked about several intake and subjective history items and how they may influence their likelihood of performing an examination of one or both hips, and these results are reported in Table 2. The hip examination tests commonly used by respondents when assessing a patient with a primary complaint of LBP are presented in Table 3. The majority of respondents reported they ‘always or most of the time’ assess hip muscle strength (94%, n = 948), passive ROM (91%, n = 921), and muscle length (90%, n = 906) within their physical examination of individuals with LBP. Other physical examination assessments that were commonly reported as performed ‘always or most of the time’ included hip active ROM (76%, n = 763), soft tissue mobility/pliability (65%, n = 700), and joint mobility (59%, n = 597).

Table 2.

Number (%) of respondents reporting various factors from the patient history that contribute to their decision to examine of one or both hip joints in individuals with a primary complaint of low back pain.a

| Always n (%) |

Most of the time n (%) |

Sometimes n (%) |

Rarely n (%) |

Never n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body diagram with marking around one or both hips (n = 1036) |

860 (83) | 122 (11.8) | 37 (3.6) | 9 (0.9) | 8 (0.7) |

| Verbal report of pain in one or both hips (n = 1033) | 903 (87.4) | 903 (87.4) | 26 (2.5) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Verbal report of stiffness in one or both hips (n = 1035) | 870 (84.1) | 120 (11.6) | 41 (4.0) | 4 (0.4) | 0 |

| Verbal report of buttock pain (n = 1034) | 782 (75.6) | 179 (17.3) | 61 (5.9) | 12 (1.2) | 0 |

| Previous surgical history in one or both hips (n = 1034) |

799 (77.3) | 168 (16.2) | 57 (5.5) | 10 (1.0) | 0 |

| Previous non-surgical history in one or both hips (n = 1034) |

800 (77.8) | 168 (16.3) | 53 (5.2) | 7 (0.7) | 0 |

| Previous surgical history in one or both knees (n = 1028) |

800 (77.8) | 168 (16.3) | 53 (5.2) | 7 (0.7) | 0 |

| Presence of neurological symptoms in the lower extremity (n = 1032) |

604 (58.5) | 271 (26.3) | 132 (12.8) | 24 (2.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Physician referral indicates presence of hip pathology (n = 1032) | 868 (84.1) | 119 (11.5) | 32 (3.1) | 12 (1.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Presence of imaging (i.e., X-ray, MRI, etc.) abnormalities of one or both hips (n = 1035) |

803 (77.6) | 156 (15.1) | 54 (5.2) | 19 (1.8) | 3 (0.3) |

| Male gender of patient (n = 1022) |

605 (59.2) | 219 (21.4) | 158 (15.5) | 18 (1.8) | 22 (2.2) |

| Female gender of patient (n = 1018) |

614 (60.3) | 220 (21.6) | 144 (14.1) | 17 (1.7) | 23 (2.3) |

The total number of respondents that answered each question is variable because some respondents did not answer every question.

Table 3.

Number (%) of respondents that use specific hip examination tests for individuals with a primary complaint of low back pain.a

| Always n (%) |

Most of the time n (%) |

Sometimes n (%) |

Rarely n (%) |

Never n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip active ROM (n = 1003) |

476 (47.5) | 287 (28.6) | 204 (20.3) | 32 (3.2) | 4 (0.4) |

| Hip passive ROM (n = 1009) | 728 (72.2) | 193 (19.1) | 79 (7.8) | 8 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) |

| Hip muscle length (n = 1010) |

651 (64.5) | 255 (25.2) | 89 (8.8) | 11 (1.1) | 4 (0.3) |

| Hip muscle strength (n = 1009) |

718 (71.2) | 230 (22.8) | 56 (5.6) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Hip joint mobility (n = 1009) |

316 (31.3) | 281 (27.8) | 309 (30.6) | 93 (9.2) | 10 (1.0) |

| Hip soft tissue mobility/pliability (n = 1009) |

369 (36.6) | 331 (28.5) | 240 (20.6) | 57 (4.9) | 12 (1.0) |

The total number of respondents that answered each question is variable because some respondents did not answer every question.

Interventions

The hip interventions commonly used when treating a patient with a primary complaint of LBP are reported in Table 4. Hip strengthening exercises were the most commonly prescribed intervention.

Table 4.

Number (%) of respondents that use specific hip interventions for individuals with a primary complaint of low back pain.a

| Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Hip strengthening exercises (n = 921) | 866 (94.0) | 55 (6.0) |

| Hip flexibility exercises (i.e., static or dynamic) (n = 905) | 814 (89.9) | 91 (10.1) |

| Hip soft tissue mobilization techniques (n = 882) | 654 (74.1) | 228 (19.6) |

| Balance/proprioception, agility/plyometric training exercises (n = 891) | 628 (70.5) | 263 (29.5) |

| Hip joint manual therapy (n = 893) | 595 (66.6) | 298 (33.4) |

| Electrophysical modalities (e.g., electrical stimulation, ultrasound) (n = 887) | 166 (18.7) | 721 (81.3) |

The total number of respondents that answered each question is variable because some respondents did not answer every question.

Hip strengthening interventions

A total of 921 respondents completed questions related to hip strengthening interventions. Ninety-four percent (n = 866) of respondents indicated they use hip strengthening interventions for individuals with LBP. Functional strengthening (e.g., weight shifts, sit to stand, squats, stepping activities) was the most common type of strengthening used. Ninety percent (n = 776) of respondents indicate they ‘always or most of the time’ utilize functional strengthening interventions in individuals with LBP. The most commonly prescribed such exercises were double leg squats (66.3%, n = 771), sit to stand (57.6%, n = 670) and forward step-ups (53%, n = 616). Non-weight bearing activities (e.g., clamshells, straight leg raise) were utilized by 74% (n = 638) of respondents, with the most common exercises prescribed in this category being single or double leg supine bridging (68.4%, n = 795) followed by sidelying clamshell (66%, n = 767) and sidelying straight leg raise into abduction (49%, n = 570).

Hip muscle flexibility interventions

A total of 905 respondents completed the questions regarding hip muscle flexibility. Ninety percent (n = 814) indicated they commonly prescribed this type of intervention targeting the hips in individuals with LBP. Static muscle stretching was reportedly ‘always or most of the time’ used by 78.5% (n = 635) of respondents, whereas only 41.6% (n = 334) used dynamic muscle stretching. For respondents who prescribed static muscle stretching exercises (n = 809), the most common muscles stretched were the piriformis (56.3%, n = 655), hamstrings (55.0%, n = 640), rectus femoris (43.3%, n = 493), iliopsoas (43.4%, n = 505) and tensor fascia latae/iliotibial band (25.1%, n = 292). For dynamic muscle stretching, responses were highly variable with an alternating lunge stance exercise reported as being used by 33.8% of respondents (n = 393).

Balance and proprioception interventions

A total of 891 respondents completed the question regarding balance and proprioception. Seventy-one percent (n = 636) of respondents reported they commonly use balance and proprioceptive exercises for individuals with LBP. Eighty percent of respondents (n = 514) reported they ‘always or most of the time’ prescribed balance and proprioceptive exercises for patients with a primary complaint of LBP. The intervention reported as performed most commonly was a single limb stance without head movement on a variable surface (e.g., foam; performed by 45%, n = 516 respondents), followed by tandem stance (36.8%, n = 428) and then by double limb stance with a narrow base of support (28.7%, n = 334).

Hip soft tissue mobilization interventions

A total of 882 respondents completed the questions regarding soft tissue mobilization techniques as an intervention strategy for individuals with LBP. Seventy-four percent (n = 654) of these respondents reportedly use soft tissue mobilization commonly for individuals with LBP. Respondents reported that they ‘always or more of the time’ use the following soft tissue mobilization techniques: trigger point release (44.4%, n = 291), myofascial release (29.0%, n = 190), massage (27.2%, n = 178), instrumented soft tissue mobilization (18.3%, n = 120), and dry needling (10.5%, n = 66). Respondents reported they commonly target several different muscles including the piriformis (88.2%, n = 577), gluteus medius (72.0%, n = 471) and iliopsoas (53.9%, n = 476.

Hip joint manual therapy interventions

A total of 893 respondents completed the questions regarding hip joint manual therapy techniques as an intervention strategy for individuals with LBP. Roughly two-thirds (n = 595) of respondents reported that they routinely used joint-focused manual therapy techniques directed at the hips for individuals with a primary complaint of LBP. Over half of these respondents reportedly use non-thrust, single plane techniques (57.9%, n = 327). Slightly less use non-thrust, combined plane techniques (44.6%, n = 239) and about a third (35.0%, n = 163) employ physiological mobilization (e.g., mobilization with movement). Only a small percentage of respondents (21%, n = 100) reported using high-velocity thrust techniques aimed at the hip joint.

Electrophysical modalities

A total of 887 respondents completed the questions related to electrophysical modalities. Relatively few respondents (18.7%, n = 166) indicated they used electrophysical modalities for the hip(s) in patients with a primary complaint of LBP. Of these respondents, the most commonly prescribed electrophysical modalities were electrical stimulation (90.3%, n = 150), thermal modalities (84.9%, n = 141), and ultrasound 31.3% (n = 52).

Relationships between participant characteristics and examination/intervention selection

There were few relationships between participant characteristics and responses to questions about the examination and intervention techniques used. Respondents who were currently enrolled or had completed post-professional fellowship training were more likely to report they used joint manual therapy techniques directed at the hips (x2 = 25.3, p = <0.001), and less likely to report using hip flexibility exercises (x2 = 7.9, p = 0.005) and electrophysical modalities (x2 = 4.3, p = 0.039), as compared to therapists who had not participated in fellowship training (Fig. 1). However, having American Board of Physical Therapy Specialities (ABPTS) specialist certification was not associated with any of the hip interventions used for patients with a primary complaint of LBP. No other variables were associated with participant responses.

Figure 1.

Associations (Pearson's χ2) between physical therapists (n = 159) having or undertaking post-professional fellowship training and their use of hip interventions in patients with a primary complaint of low back pain.

Discussion

Current clinical practice guidelines for LBP recommend examination and intervention aimed at the hip(s), although there is little guidance as to what aspects of the hip are most relevant to optimize patient outcomes.1 Physical therapy interventions directed at the hip(s) for individuals with LBP remains controversial. Our survey found that physical therapists in the United States are commonly performing an examination and providing interventions directed at the hip(s) for individuals with LBP. The most common physical examinations of the hip were for strength, passive ROM and muscle flexibility, consistent with the most frequently used interventions of hip strengthening and flexibility exercises. Hip strengthening exercises most commonly included functional strengthening (e.g., squatting and stepping activities). Hip flexibility exercises most commonly targeted the hamstrings and piriformis.

Physical therapist reported practices were not always consistent with the current evidence for hip treatment in individuals with LBP. Notably, despite current evidence not supporting the usage of soft tissue mobilization for individuals with a primary complaint of LBP and studies suggesting a favourable response with hip joint manual therapy techniques, hip soft tissue mobilization was used by more respondents (74%) compared to hip joint manual therapy techniques (67%).3, 15, 19, 20 Furlan et al.20 performed a Cochrane review of massage techniques for individuals with LBP and concluded that massage may provide some short-term improvement in symptoms, but only when compared to an inactive-control such as a sham, waitlist or no treatment.20 However, outcomes with massage were not favourable when compared to an active control such as manual therapy (i.e., thrust or non-thrust, mobilization with movement techniques), exercise or education. Comparatively, a recent randomized clinical trial by Bade and colleagues reported that a combination of joint manual therapy and exercise directed at the hip(s) resulted in a favourable outcome compared to interventions only directed at the lumbar spine.19 There may be several potential reasons why respondents in the present study reported using ‘manual’ techniques in a manner inconsistent with the published evidence, including lack of appropriate training in entry-level programmes, lack of confidence with performing joint-related techniques, lack of awareness of current best evidence and challenges associated with changing current practice patterns. Our study did not explore the reasons participants chose to perform particular manual techniques, therefore the rationale for therapists employing soft tissue mobilization techniques remains speculative.

The only participant characteristic associated with reported clinical practice patterns related to the hip in patients with LBP was having or currently undertaking post-professional fellowship training. Recent evidence demonstrates that having post-professional fellowship training has a positive influence on patient outcomes and individuals with post-professional training are more likely to adhere to clinical practice guideline recommendations.21, 22 In the current survey, participants currently enrolled in or having completed a post-professional fellowship were more likely to use hip joint manual therapy (x2 = 25.3, p < 0.001) and less likely to utilize hip flexibility exercises (x2 = 7.9, p = 0.005) and modalities (x2 = 4.3, p = 0.039). The use of hip joint manual therapy is more consistent with contemporary evidence.3, 15, 19 No significant differences in intervention selection were found for those participants that obtained ABPTS specialty certification only, compared to those without ABPTS certification. These results suggest that post-professional fellowship training is more likely to result in changes to intervention selections compared to obtaining a clinical specialization certification alone.

Several limitations may have influenced the findings of this study. First, the response rate was low which may indicate that the findings are not representative of all physical therapists. Secondly, the survey was administered to APTA Sports and Orthopaedic Section members, as well as members of American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT), which may limit generalizability of the findings to non-members of these organizations. Specifically, members of AAOMPT may have a greater interest in manual therapy techniques and thus led to a higher proportion of respondents reporting the use of manual therapy. We selected members of these professional groups for recruitment despite possible sampling bias because we wished to target physical therapists in musculoskeletal practice settings, and the majority of members of these groups would likely work in such settings. Furthermore, as this survey was a snapshot of therapists who responded to the questionnaire, it represents the practices of those respondents and may not be a complete and accurate representation of the practices of the entire musculoskeletal physical therapy community within the United States. Potential respondents may have been more inclined to complete the survey if they already had knowledge in this topic area or commonly examined or treated the hip in patients with LBP. Third, it is possible that bias may have resulted from wording or terminology used in this survey. While examples were provided for clarification (e.g., single leg stance, on variable surface with head motion), some terms may not have been consistent with the terminology a particular therapist typically uses. Finally, the results may not be reflective of physical therapy practices in some other countries.

Conclusion

The results of this survey indicate that most physical therapists adhere to clinical guidelines which suggest the hip(s) should be examined and treated in individuals presenting with a primary complaint of LBP, however the aspects of examination and intervention commonly utilized were variable. Participants indicated that the most common hip examination items were muscle strength, passive range of motion, and muscle length. The most commonly reported interventions directed at the hip(s) include hip strengthening exercise, muscle stretching and soft tissue mobilization techniques. Post-professional education was associated with the selection of interventions targeting the hip(s) in individuals with LBP, specifically more common usage of hip joint manual therapy techniques. These findings suggest that post-professional fellowship training results in changes to clinical practice patterns, at least in regards to the treatment of individuals with LBP.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Delitto A., George S.Z., Van Dillen L.R. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1–A57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.42.4.A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster N.E., Anema J.R., Cherkin D. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–2383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns S.A., Mintken P.E., Austin G.P., Cleland J. Short-term response of hip mobilizations and exercise in individuals with chronic low back pain: a case series. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:100–107. doi: 10.1179/2042618610Y.0000000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper N.A., Scavo K.M., Strickland K.J. Prevalence of gluteus medius weakness in people with chronic low back pain compared to healthy controls. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(4):1258–1265. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penney T., Ploughman M., Austin M.W., Behm D.G., Byrne J.M. Determining the activation of gluteus medius and the validity of the single leg stance test in chronic, nonspecific low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(10):1969–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roach S.M., Juan J.G.S., Suprak D.N., Lyda M., Bies A.J., Boydston C.R. Passive hip range of motion is reduced in active subjects with chronic low back pain compared to controls. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(1):13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutherlin M.A., Hart J.M. Hip-abduction torque and muscle activation in people with low back pain. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(1):51–61. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2013-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shum G.L.K., Crosbie J., Lee R.Y.W. Effect of low back pain on the kinematics and joint coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit. Spine. 2005;30(17):1998–2004. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000176195.16128.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shum G.L.K., Crosbie J., Lee R.Y.W. Movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during a picking up activity in low back pain subjects. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(6):749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung P.S. A compensation of angular displacements of the hip joints and lumbosacral spine between subjects with and without idiopathic low back pain during squatting. J Electromyogr Kinesiol Off J Int Soc Electrophysiol Kinesiol. 2013;23(3):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dillen L.R., Bloom N.J., Gombatto S.P., Susco T.M. Hip rotation range of motion in people with and without low back pain who participate in rotation-related sports. Phys Ther Sport Off J Assoc Chart Physiother Sports Med. 2008;9(2):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redmond J.M., Gupta A., Hammarstedt J.E., Stake C.E., Domb B.G. The hip-spine syndrome: how does back pain impact the indications and outcomes of hip arthroscopy? Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc. 2014;30(7):872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy D.R., Byfield D., McCarthy P., Humphreys K., Gregory A.A., Rochon R. Interexaminer reliability of the hip extension test for suspected impaired motor control of the lumbar spine. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(5):374–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prather H., Cheng A., Steger-May K., Masheshwari V., Van Dillen L. Hip and lumbar spine physical examination findings in people presenting with low back pain, with or without lower extremity pain. JOSPT. 2017;47(3):163–172. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns S.A., Mintken P.E., Austin G.P. Clinical decision making in a patient with secondary hip-spine syndrome. Physiother Theory Pract. 2011;27:384–397. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2010.509382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stolze L.R., Allison S.C., Childs J.D. Derivation of a preliminary clinical prediction rule for identifying a subgroup of patients with low back pain likely to benefit from Pilates-based exercise. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(5):425–436. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter S. Effectiveness of targeted home-based hip exercises in individuals with non-specific chronic or recurrent low back pain with reduced hip mobility: arandomised trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2015;28(4):811–825. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendall K.D., Emery C.A., Wiley J.P., Ferber R. The effect of the addition of hip strengthening exercises to a lumbopelvic exercise programme for the treatment of non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport Sports Med Aust. 2014;18(6):626–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bade M.J., Cobo-Estevez M., Neeley D., Pandya J., Gunderson T., Cook C. Effects of manual therapy and exercise targeting the hips in patients with low back pain – a randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;00:1–7. doi: 10.1111/jep.12705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlan A.D., Giraldo M., Baskwill A., Irvin E., Imamura M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD001929. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodeghero J., Wang Y.C., Flynn T., Cleland J.A., Wainner R.S., Whitman J.M. The impact of physical therapy residency or fellowship education on clinical outcomes for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. JOSPT. 2015;45(2):86–96. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madson T.J., Hollman J.H. Lumbar traction for managing low back pain: a survey of physical therapists in the United States. JOSPT. 2015;45(8):586–595. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]