Abstract

Background

To increase the pharmacological effects of red ginseng (RG, the steamed root of Panax ginseng Meyer), RG products modified by heat process or fermentation have been developed. However, the antiallergic effects of RG and modified/fermented RG have not been simultaneously examined. Therefore, we examined the allergic rhinitis (AR)-inhibitory effects of water-extracted RG (wRG), 50% ethanol-extracted RG (eRG), and bifidobacteria-fermented eRG (fRG) in vivo.

Methods

RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate/A23187. Mice with AR were prepared by treatment with ovalbumin. Allergic markers IgE, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-4, and IL-5 were assayed in the blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, nasal mucosa, and colon using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mast cells, eosinophils, and Th2 cell populations were assayed using a flow cytometer.

Results

RG products potently inhibited IL-4 expression in phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate/A23187-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. Of tested RG products, fRG most potently inhibited IL-4 expression. RG products also alleviated ovalbumin-induced AR in mice. Of these, fRG most potently reduced nasal allergy symptoms and blood IgE levels. fRG treatment also reduced IL-4 and IL-5 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, nasal mucosa, and reduced mast cells, eosinophils, and Th2 cell populations. Furthermore, treatment with fRG reduced IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 levels in the colon and restored ovalbumin-suppressed Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations and ovalbumin-induced Firmicutes population in gut microbiota. Treatment with ginsenoside Rd significantly alleviated ovalbumin-induced AR in mice.

Conclusion

fRG and ginsenoside Rd may alleviate AR by suppressing IgE, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression and restoring the composition of gut microbiota.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Fermentation, Ginsenoside Rd, Gut microbiota, Red ginseng

1. Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common inflammatory disease, which occurs in the nose by the overreaction of allergens. The AR prevalence is estimated to be up to 10% of the world population. AR is triggered in the nasal membrane by environmental allergens interacting with IgE [1], [2]. Although not fatal, irritable symptoms, including itching, sneezing, and nasal congestion, reduce the quality of life in patients with AR [3], [4]. These symptoms are principally caused by allergic and inflammatory mediators released from mast cells (MCs), basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and epithelial cells, which are engaged in innate and adaptive immunities [5], [6], [7]. Moreover, IgE, interleukin (IL)-4, and IL-5 expressions are extremely upregulated in patients with AR, whereas IL-10 expression is downregulated [8], [9]. Among these immune cells, MCs, eosinophils, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages are activated by the stimulation with the complex of IgE and allergens and secrete tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-4, IL-5, and histamine. These stimulate the adaptive immune cells including T lymphocytes and differentiate naive CD4+ T cells into effector T cells such as T helper Type 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17, and regulatory T (Treg) cells [10]. MCs release histamine and cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-5, triggering acute and chronic allergic responses [11]. Of these allergic mediators, IL-4 and IL-5 promote Th2 cell differentiation, induce IgE production from B lymphocytes, and activate eosinophils, whereas IL-10 stimulates Treg cell differentiation and suppresses Th2 cell activation and IgE expression [12], [13]. To remit AR, H1 receptor antagonists, corticosteroids, antileukotrienes, and decongestants are frequently used [14]. However, these treatments can evoke adverse side effects.

Red ginseng (RG, the steamed root of Panax ginseng Meyer, family Araliaceae) is frequently used as a functional food and herbal medicine for the therapy of cancer, allergic and inflammatory disorders, and diabetes [15], [16]. Its major constituents are ginsenosides, which exhibit antitumor, antiinflammatory, antiallergic, and antidiabetic effects [15], [16], [17], [18]. These ginsenosides including ginsenosides Rb1 and Rb2 suppressed compound 48/80–induced itching behaviors and inflammation [19], [20]. However, these ginsenosides are transformed to ginsenosides Rd, F2, and compound K by gut microbiota or fermentation [18], [21], [22]. These transformed ginsenosides such as ginsenosides Rd and compound K show biological activities more potently than parental ginsenosides. Therefore, to enforce the pharmacological effects of RG, many kinds of RG modified by heat process or fermentation have been developed [22], [23], [24]. For example, compound K–rich RG fermented by bifidobacterial lysate attenuates the nasal congestion in patients with rhinitis [25]. However, the difference between the anti-AR effects of RG and fermented RG (fRG) is not examined.

In the preliminary study, RG inhibited IL-4 expression in phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)/A23187-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. Moreover, when RG was orally administered, a main constituent absorbed into the blood was ginsenoside Rd [26], [27]. Herein, to understand the pharmacological effects of various RG products, we examined anti-AR effects of water-extracted RG (wRG), 50% ethanol-extracted RG (eRG), fRG, and their main constituent ginsenoside Rd in mice with ovalbumin-induced AR.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Ovalbumin, PMA, A23187, and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α were supplied from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The ELISA kit for IgE was purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). Protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were purchased from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany). The fecal DNA isolation kit was purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). phycoerythri (PE)-conjuaged anti–Siglec-F, and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjuaged anti-F4/80, PE-conjugated anti-FcεRIα, APC-conjugated anti-CD117, PE-conjugated anti–IL-4, peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP)-conjuaged anti-CD4, and fixation/permeabilization buffer were purchased from BioGems International Inc. (Westlake Village, CA, USA). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) lysing solution was purchased from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA, USA). RG products (eRG, fRG, and wRG) were purchased or prepared according to the method used by Kim et al [27] (Supplement Table 1 and Supplement Fig. 1). Ginsenoside Rd was prepared according to the method used by Bae et al [28].

2.2. Culture of RBL-2H3 cells

Cells were cultured in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% carbon dioxide at 37°C in Dulbecco modified eagle medium (DMEM), which contained 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution and 10% fetal bovine serum. To examine the effects of RG products and ginsenoside Rd on IL-4 expression, the cells (3 × 105 cells/mL) were incubated with PMA (50 nM)/A23187 (1 μM) in the addition or absence of RG products (10 μg/mL) and ginsenoside Rd (10 μM) for 18 h, lysed with lysis buffer, and centrifuged (10,000 g for 5 min) according to the modified method used by Chen et al. [29]. IL-4 levels were measured in the supernatant by the ELISA kit.

2.3. Animals

BALB/c mice (female, 6 weeks old, 19–21 g) were purchased from Orient Bio Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The mice were kept in wire cages in a ventilated room of the animal laboratory (temperature, 20–22°C; humidity, 50 ± 10%; and light, 07:00–19:00; not specific pathogen–free) approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, fed a standard laboratory diet, and allowed to take water ad libitum. All experiments were carried out according to the Kyung Hee University Guidelines for Laboratory Animals Care and Use and approved by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at the university (IRB No. KHUASP(SE)-17-104).

2.4. Preparation of ovalbumin-induced AR mice

Mice with AR were manipulated according to the modified method used by Oh et al [30]. Briefly, the mice were randomly separated. Each group consisted of eight mice. The mice were sensitized by intraperitoneally injecting ovalbumin (20 μg, dissolved in 2 mg/200 μL of aluminum potassium sulfate solution) on the 1st and 14th day and intranasally treated by daily dropping ovalbumin (10 μL into the nostril [10 mg/mL], dissolved in saline) from the 26th to 28th day. Test agents (vehicle, saline; eRG, 50 mg/kg of eRG per-oral (p.o.); fRG, 50 mg/kg of fRG p.o.; wRG, 50 mg/kg of wRG p.o.; Rd, 20 mg/kg of ginsenoside Rd p.o.; and Dx, 1 mg/kg of dexamethasone intraperitoneally (i.p.)) were orally gavaged once a day from the 26th to 30th day. The control group was given saline instead of RG products and ovalbumin. On the 31st day, the mice were intranasally treated with ovalbumin (10 μL into the nostril [10 mg/mL], dissolved in physiological saline) and counted for AR behaviors (symptom score indicates number of rubbing and scratching of the nose, ear, and eyes for 10 min) [31].

2.5. Hisotological examination

Noses were fixed overnight in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde, frozen in optimal cutting temperature solution, cut into 10-μm section using a cryostat, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and then observed under a light microscope [32].

2.6. Analysis of eosinophils, MCs, and Th2 cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid using a flow cytometer

The mice were sacrificed and incised over the larynx, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was taken out thrice using 3 mL of complete media, centrifuged (5000 g, 5 min), suspended in fixation/permeabilization solution, and incubated for 5 min. Specific monoclonal antibodies (1 μg/100 μL: PE-conjugated antibody for Siglec-F and APC-conjugated antibody for F4/80 to measure eosinophils, PE-conjugated antibody for FcεRIα and APC-conjugated antibody for CD117 to measure MCs, and PE-conjugated antibody for IL-4 and PerCP-conjugated antibody for CD4 to measure Th2 cells) were added to the samples (2 × 106 cells/mL) and treated at 4°C for 45 min in the dark [31]. The stained cells were treated with the fixation buffer, lysed with the FACS lysing solution, washed, suspended in FACS buffer, and counted using a flow cytometer.

2.7. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

For the determination of cytokines and IgE, the nasal mucosa and colon were minced with a homogenizer, lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer, which contained 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, on ice. The nasal mucosa and colon homogenates and BALF were centrifuged (15,000 g, 4°C, 15 min for the nasal mucosa and colon and 5000 g, 5 min for BALF) [32]. Levels of TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-5 in the supernatants of tissue homogenates and BALF and IgE, IL-4, and IL-5 in the sera, which were obtained from blood by centrifugation (1,500 g, 15 min), were assayed using commercial ELISA kits.

2.8. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, δ/γ-Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria was performed with total DNA(100 ng) purified from the feces in a Takara thermal cycler using SYBER premix (Takara Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan) [33]. Thermal cycling was performed at 95°C for 30 s with 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s and amplification at 63°C for 30 s. Expression of genes was computed relatively to bacterial rRNA, using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA). The primers were prepared in Macrogen (Seoul, Korea), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in the present study.

| Primer sequence |

||

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| Firmicutes | 5′-GGA GYA TGT GGT TTA ATT CGA AGC A-3′ | 5′-AGC TGA CGA CAA CCA TGC AC-3′ |

| Bacteroidetes | 5′-AAC GCG AAA AAC CTT ACC TAC C-3′ | 5′-TGC CCT TTC GTA GCA ACT AGT G-3′ |

| Actinobacteria | 5′-TGT AGC GGT GGA ATG CGC-3′ | 5′-AAT TAA GCC ACA TGC TCC GCT-3′ |

| Bacterial 16S rRNA | 5′-TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG GTG CCA GCM GCC GCG GTA A-3′ | 5′-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA GGG ACT ACH VGG GTW TCT AAT-3′ |

| IL-13 | 5′-GGAATCCAGGGCTACA CAGA-3′ |

5′-AGGAGCTGAGCAACATC ACA-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-TGCAGTGGCAAAGTGG AGAT-3′ |

5′-TTTGCCGTGAGTGGAGT CATA-3′ |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IL, interleukin

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for IL-13 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was performed with total DNA (100 ng) purified from the colons in a Takara thermal cycler using SYBER premix [27]. Thermal cycling was performed at 95°C for 30 s with 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s and amplification at 72°C for 30 s. Expression of genes was computed relatively to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, using Microsoft Excel. The primers were prepared in Macrogen, as shown in Table 1.

2.9. Statistics

All data values obtained are indicated as mean ± standard deviation. The significant difference was statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. fRG and ginsenoside Rd inhibited the expression of IL-4 in RBL-2H3 cells

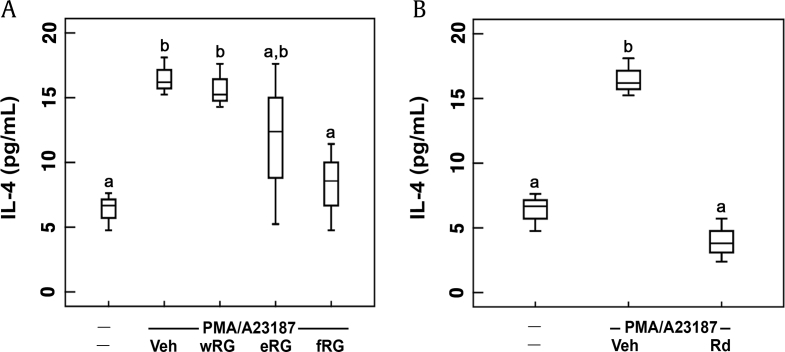

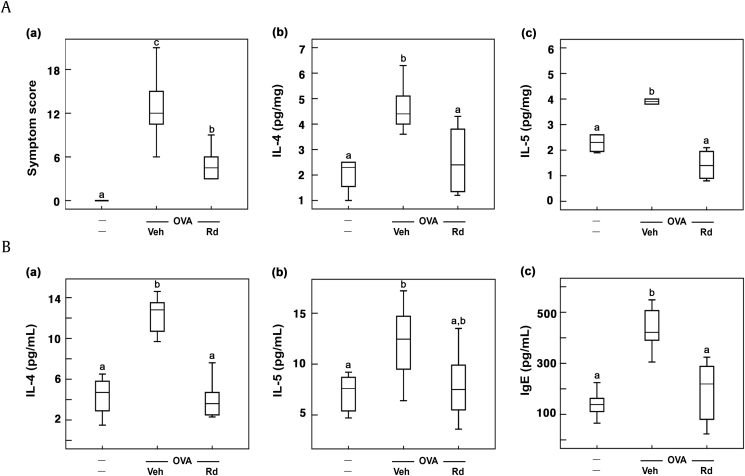

RBL-2H3 cells are similar to the function of primary MCs and basophils [34]. PMA/A23187 promotes MC and basophil activation and upregulate the secretion of allergy-related factors [29], [35]. Therefore, PMA/A23187-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells are frequently used for the study of MC-mediated allergic responses. First, in order to evaluate the inhibitory effects of RG products in vitro against MC-mediated AR, we examined the effects of wRG, eRG, and fRG on the expression of IL-4 in PMA/A23187-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 1A). Treatment with PMA/A23187 significantly increased IL-4 expression while RG treatments suppressed PMA/A23187-induced IL-4 expression. Of these treatments, fRG treatment most potently suppressed IL-4 expression. Furthermore, ginsenosided Rd, a main constituent of fRG, also potently inhibited IL-4 expression (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of wRG, eRG, fRG, and ginsenoside Rd on IL-4 expression in PMA/A23187-induced RBL-2H3 cells. (A) Effects of wRG, eRG, and fRG. (B) Effects of ginsenoside Rd. RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated with PMA/A23187 in the presence of fRG, eRG, wRG (10mg/mL), or ginsenoside Rd (10 mM) for 18 h. Data are shown as box plots (n=4). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p<0.05). eRG, ethanol-extracted RG; fRG, fermented RG; IL, interleukin; RG, red ginseng; Veh, vehicle;wRG, water-extracted RG.

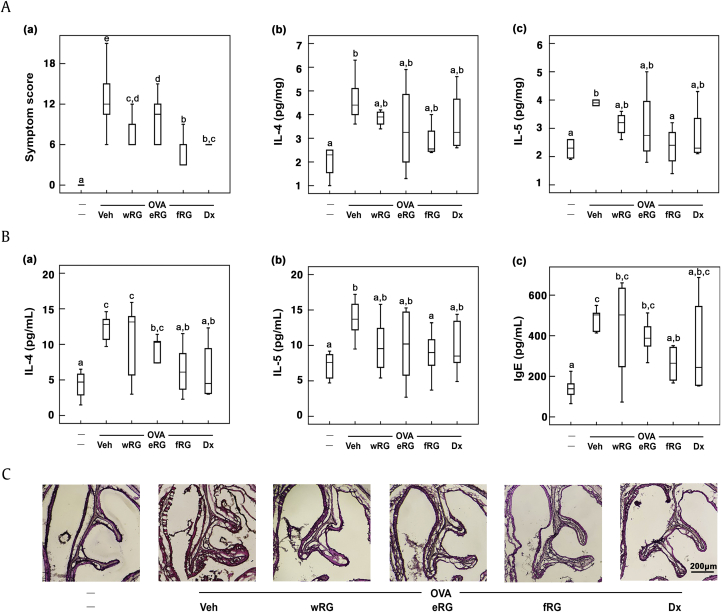

3.2. fRG alleviated ovalbumin-induced AR in mice

Then, we examined the antiallergic effect of RG on mice with ovalbumin-induced AR. Treatment with ovalbumin showed nasal allergy symptoms such as sneezing and nose scratching. Furthermore, ovalbumin treatment increased nasal IL-4 and IL-5 levels (Fig. 2). However, treatment with RG significantly alleviated ovalbumin-induced nasal allergy symptoms and reduced nasal IL-4 and IL-5 expression. Among the tested RG products, fRG treatment most potently suppressed nasal IL-4 and IL-5 expression. fRG treatment also suppressed ovalbumin-induced dilation of nasal epithelial cells, assessed by histological examination.

Fig. 2.

Effects of wRG, eRG, and fRG on the nasal allergic symptoms and allergic rhinitis (AR) marker expression in the nasal mucosa and blood of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced AR. (A) Effects on (a) the nasal allergy symptoms, (b) nasal IL-4 levels, and (c) IL-5 levels. (B) Effects on blood (a) IL-4, (b) IL-5, and (c) IgE levels. (C) Histological examination of nasal tissues, stained with H&E. Cytokine and IgE levels were measured using ELISA kits. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle, wRG [50 mg/kg/day], eRG [50 mg/kg/day], fRG [50 mg/kg/day], or dexamethasone [Dx, 1 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally (for wRG, eRG, and fRG) or intraperitoneally (for Dx) daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

AR, allergic rhinitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; eRG, ethanol-extracted RG; fRG, fermented RG; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IL, interleukin; RG, red ginseng; Veh, vehicle; wRG, water-extracted RG.

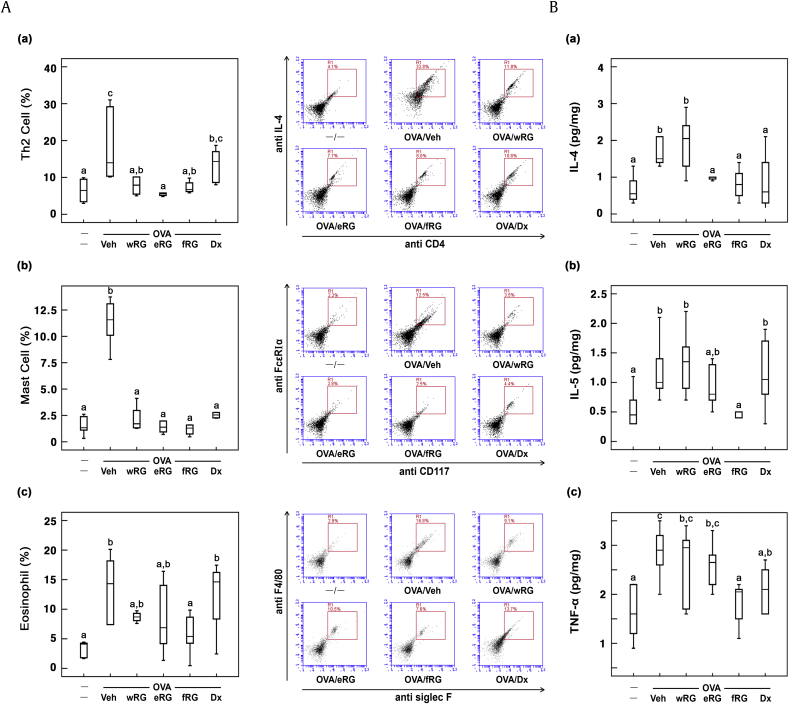

Ovalbumin treatment also increased MCs, eosinophils, and Th2 cell populations in the BALF (Fig. 3). However, treatment with RG products suppressed ovalbumin-induced populations of MCs, eosinophils, and Th2 cells. Of these, fRG treatment most potently reduced MCs, eosinophils, and Th2 cell populations. Furthermore, fRG treatment suppressed ovalbumin-induced IL-4 and IL-5 expression in the BALF. fRG treatment also suppressed ovalbumin-induced IL-4, IL-5, and IgE levels in the blood.

Fig. 3.

Effects of wRG, eRG, and fRG on Th2 cells, eosinophils, and mast cells populations and IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α levels in the BALF of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced AR. (A) Effects on (a) Th2 cells, (b) mast cells, and (c) eosinophils. The populations of cells were measured by FACS. (B) Effects on (a) IL-4, (b) IL-5, and (c) TNF-α levels. Cytokine levels were measured using ELISA kits. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle, wRG [50 mg/kg/day], eRG [50 mg/kg/day], fRG [50 mg/kg/day], or dexamethasone [Dx, 1 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally (for wRG, eRG, and fRG) or intraperitoneally (for Dx) daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

AR, allergic rhinitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; eRG, ethanol-extracted RG; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; fRG, fermented RG; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IL, interleukin; RG, red ginseng; Veh, vehicle; wRG, water-extracted RG.

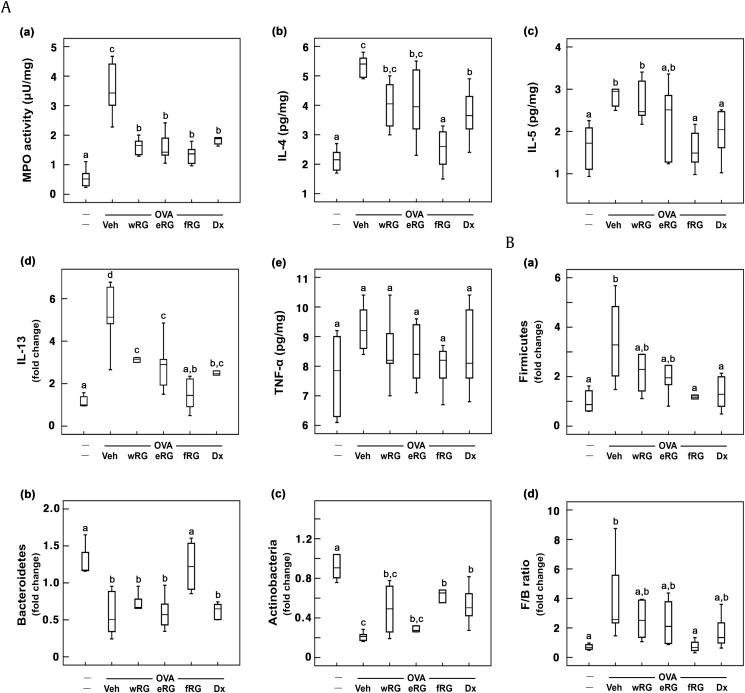

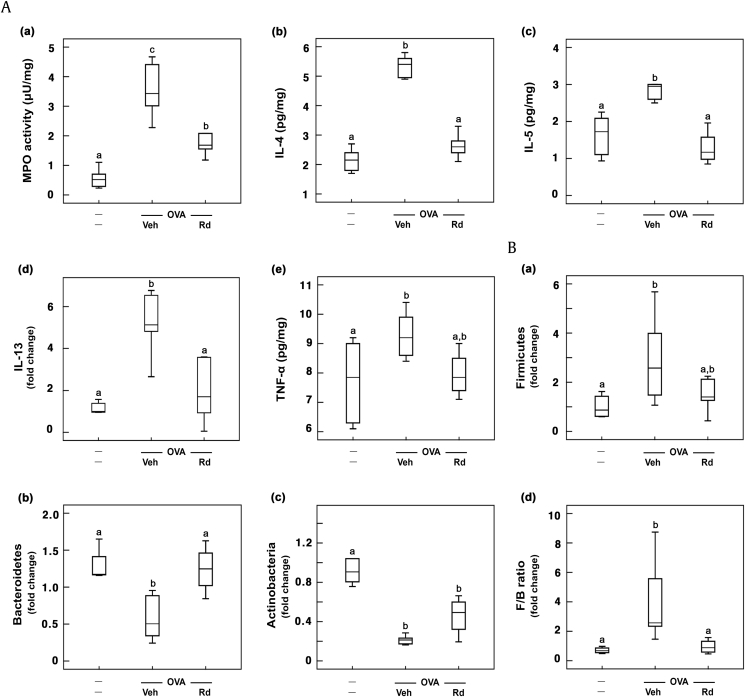

To understand the effect of RG on gut microbiota composition and allergic cytokine expression in the colon, we investigated its effect on gut microbiota population, colonic IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression, and myeloperoxidase activity in mice with ovalbumin-induced AR (Fig. 4). Ovalbumin treatment significantly increased Firmicutes population and reduced Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations. However, RG treatments reduced Firmicutes population and increased Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations, resulting in the decrease of Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio. Of RG products, fRG significantly increased Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations and reduced Firmicutes population. Dexamethasone, a positive agent, increased the population of Actinobacteria, not Bacteroidetes, and suppressed the population of Firmicutes. Ovalbumin treatment also increased colonic IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression in the colon, whereas RG treatment significantly inhibited ovalbumin-induced expression of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Furthermore, RG treatment suppressed myeloperoxidase activity in the colon. Of these, fRG treatment most potently suppressed myeloperoxidase activity and IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression.

Fig. 4.

Effects of wRG, eRG, and fRG on myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 expression in the colon and gut microbiota population in the feces of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced AR. (A) Effects on (a) myeloperoxidase activity, (b) IL-4, (c) IL-5, (d) IL-13, and (e) TNF-α expression. Cytokines were measured using ELISA kits. (B) Effects on fecal (a) Firmicutes, (b) Bacteroidetes, (c) Actinobacteria populations, and (d) Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio. Gut microbiota populations were analyzed using qPCR. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle, wRG [50 mg/kg/day], eRG [50 mg/kg/day], fRG [50 mg/kg/day], or dexamethasone [Dx, 1 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally (for wRG, eRG, and fRG) or intraperitoneally (for Dx) daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

AR, allergic rhinitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; eRG, ethanol-extracted RG; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; fRG, fermented RG; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IL, interleukin; RG, red ginseng; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Veh, vehicle; wRG, water-extracted RG.

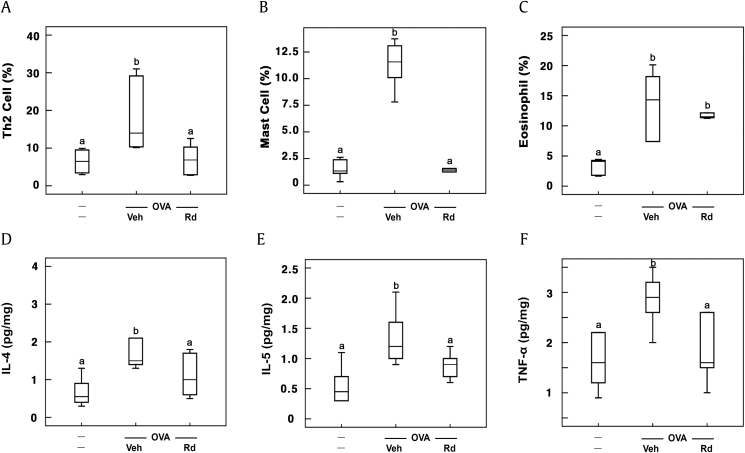

3.3. Ginsenoside Rd alleviated ovalbumin-induced AR in mice

Thereafter, to understand whether ginsenoside Rd, which was the most abundantly absorbed ginsenoside in mice orally treated with wRG or fRG [32], could alleviate AR in vivo, we examined the effect of ginsenoside Rd on mice with ovalbumin-induced AR. Ginsenoside Rd treatment significantly attenuated ovalbumin-induced nasal allergy symptoms and reduced nasal IL-4 and IL-5 levels in the nasal mucosa (Fig. 5A). Ginsenoside Rd treatment also suppressed ovalbumin-induced IL-4 and IL-5 expression in the blood (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, ginsenoside Rd treatment reduced ovalbumin-induced populations of MCs, eosinophils, and Th2 cells (Fig. 6A). Ginsenoside Rd treatment suppressed ovalbumin-induced IL-4 and IL-5 expression in BALF (Fig. 6B). Moreover, ginsenoside Rd treatment reduced ovalbumin-induced IgE levels in the blood. Ginsenoside Rd treatment significantly suppressed ovalbumin-induced myeloperoxidase activity and IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression in the colon and increased ovalbumin-suppressed fecal Bacteroidetes population (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

Effect of ginsenoside Rd on the nasal allergy symptoms and allergic rhinitis (AR) biomarker expression in the nasal mucosa and blood of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced AR. (A) Effect on (a) nasal allergy symptoms and (b) nasal IL-4 and (c) IL-5 levels. (B) Effect on blood (a) IL-4, (b) IL-5, and (c) IgE levels. Cytokine and IgE levels were measured using ELISA kits. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle or ginsenoside Rd [20 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin; Veh, vehicle.

Fig. 6.

Effect of ginsenoside Rd on Th2 cells, eosinophils, and mast cell populations and IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α levels in the BALF of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced rhinitis (OAR). Effects on (A) Th2, (B) mast cells, (C) and eosinophils. The populations of cells were measured by FACS. Effects on (D) IL-4, (E) IL-5, and (F) TNF-α levels. Cytokine levels were measured using ELISA kits. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle or ginsenoside Rd [20 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

AR, allergic rhinitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Veh, vehicle.

Fig. 7.

Effect of ginsenoside Rd on myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 expression in the colon and gut microbiota population in the feces of mice with ovalbumin (OVA)-induced AR. (A) Effects on (a) myeloperoxidase activity, (b) IL-4, (c) IL-5, (d) IL-13, and (e) TNF-α expression. IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-α levels were measured using ELISA kits. IL-13 level was measured using qPCR. (B) Effects on fecal (a) Firmicutes, (b) Bacteroidetes, (c) Actinobacteria populations, and (d) Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio. Gut microbiota populations were analyzed by qPCR. The control group was treated with vehicle instead of OVA and test agents. Test agents (vehicle or ginsenoside Rd [20 mg/kg/day]) were administered orally daily for 5 days for treating mice with OVA-induced AR. Data are shown as box plots (n = 8). Means with the same letters are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

AR, allergic rhinitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Veh, vehicle.

4. Discussion

Ginseng, including RG (steamed ginseng), exhibits a variety of pharmacological properties, including anticancer, antiallergic, antiinflammatory, and antipruritic effects [15], [16]. The main bioactive components of ginseng are ginsenosides and polysaccharides [18]. RG is prepared by steaming fresh ginseng. Steaming partially transforms the constituents of ginseng, particularly ginsenosides [18], [23]. Fresh and white ginsengs contain ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, and Rc as main constituents, whereas the main constituents of RG are ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg3. Jeong et al [36] reported that RG decreased airway resistance, eosinophil population in BALF, and blood IgE levels in rodents with ovalbumin-induced asthma. Kim and Yang [37] reported that RG suppressed airway hyperresponsiveness by suppressing T cells and eosinophil infiltration, their cytokine secretion, and blood IgE levels in mice with ovalbumin-sensitized asthma. Lee and Cho [38] reported that RG reduced IgE levels and increased Foxp3+ T cell populations in NC/Nga mice. Babayigit et al [39] reported that oral administration of RG prevented chronic airway remodeling in a murine asthma model. Jung et al [25] reported that bifidobacterial lysate–treated RG, which was not fermented with live bifidobacteria, attenuated allergic syndrome in patients with AR. These results suggest that RG can reduce IgE level and increase Treg cell population, resulting in the attenuation of asthma and AR. However, the difference in antiallergic activities between RG and fRG was not examined.

In the present study, we found that fRG potently inhibited IL-4 expression in PMA/A23187-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells, which exhibit the immune function such as allergen-induced MCs [29]. These results suggest that fRG can alleviate MC-mediated AR. We also observed that ovalbumin-treated mice exhibited AR symptoms and increased Th2 cell population and IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IgE expression, as previously reported [40], [41]. Furthermore, the induction of AR by ovalbumin treatment altered gut microbiota composition: it increased the Firmicutes population and reduced Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations. These findings suggest that allergen-induced allergic diseases can be companied by the disturbance of gut microbiota including the increased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. However, treatment with RG products, particularly fRG, inhibited the expression of IL-4 and IL-5 in the nasal mucosa, BALF, and blood of mice. fRG also suppressed the infiltration of eosinophils, MCs, and Th2 cells into the BALF of mice with ovalbumin-induced AR. In the in vitro study, RG products, particularly fRG, inhibited the expression of IL-4 in RBL-2H3 cells stimulated by PMA/A23187. These findings suggest that this fRG can inhibit the activation of eosinophils and MCs and differentiation into Th2 cells by suppressing the expression of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the immune cells. fRG also reduced IgE levels in the blood and nasal allergy symptoms. Furthermore, fRG suppressed the expression of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the colon and BALF. fRG significantly increased ovalbumin-suppressed Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations and reduced ovalbumin-induced Firmicutes population: fRG-induced Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria populations were inversely proportional to the IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression in the colon and BALF, whereas the Firmicutes population was directly proportional. These findings suggest that fRG may alleviate AR by regulating gut immunity and microbiota composition.

Many studies have suggested that the immunomodulating components of RG should be ginsenosides and polysaccharides [15], [18], [42]. Ginsenosides, which are main constituents of RG, have antiallergic activities in murine asthma and atopic disease models [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]. Ginsenosides, including ginsenoside Rd, also inhibited inflammation in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB and increased immunological adjuvant activity by inducing the expression of interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10, which are Th1 and Th2 cytokines [45], [47], [48]. Bae et al [46], [49] reported that treatment of mice with ginsenoside Rb1 or its metabolite CK suppressed IgE–antigen complex-induced passive cutaneous anaphylaxis by suppressing the expression of IL-4 and TNF-α and activation of NF-κB. Ginsenoside Rg1 enhanced the development of Th2 cells from the naive CD4+ T cells in murine splenocytes by increasing the expression of IL-4, a Th2-specific cytokine [44]. CK inhibited the expression of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS) in macrophages stimulated by LPS and in mice with 2,3,4-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)- or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation [50]. CK increased the DC development from monocytes by increasing the expression of IFN-γ and proliferation of Th1 cells [45], [50]. CK suppressed the T cell activation and increased naive T and Treg cell populations in the spleens of rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis [47], [48]. Ginseng polysaccharides enhanced Th1 function in the irradiated mice while Th2 cell response was interfered [42]. These findings suggest that ginsenosides including ginsenoside Rd can regulate innate and adaptive immune responses: they inhibited monocyte activation, inflammation, and hypersensitivity, activated Th1 cell activation, and increased Treg cell differentiation and DC maturation. Polysaccharides mainly induce macrophage and Th1 cell activation. Moreover, polysaccharides are not easily absorbed compared with saponins. In addition, when RG was orally administered, the protopanaxadiol-type component highly absorbed into the blood was ginsenoside Rd, followed by ginsenosides Rg3, CK, and F2 in rodents. Therefore, pharmacological activities of RG can be dependent on the absorbed level of ginsenoside Rd. Moreover, the absorbed ginsenoside Rd level was significantly higher in the blood of mice orally gavaged with fRG than in those with RG, whereas the absorbed Rg3 level was not different [27]. Moreover, in the present study, ginsenoside Rd potently suppressed ovalbumin-induced nasal AR symptoms, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression, and MCs, eosinophils, and Th2 cell populations and restored ovalbumin-induced disruption of gut microbiota composition in mice with ovalbumin-induced AR. Ginsenoside Rd also inhibited IL-4 expression in PMA/A23187-induced RBL-2H3 cells in vitro. These findings suggest that the anti-AR activities of fRG may be dependent on those of highly absorbed ginsenoside Rd, which may directly suppress allergic responses and the indirect regulation of gut immunity through the modification of gut microbiota composition in the intestine before the absorption of fRG constituents.

In conclusion, fRG and ginsenoside Rd may alleviate AR by suppressing IgE, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 expression and restoring the composition of gut microbiota.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Medical Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2017R1A5A2014768).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2019.02.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Stephani J., Radulovic K., Niess J.H. Gut microbiota, probiotics and inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2011;59:161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skoner D.P. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathan R.A. The rhinitis control assessment test: implications for the present and future. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:13–19. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000020. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.P Eifan A.O., Durham S.R. Pathogenesis of rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:1139–1151. doi: 10.1111/cea.12780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durham S.R. The inflammatory nature of allergic disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(Suppl 6):20–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.0280s6020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawankar R. Mast cells in allergic airway disease and chronic rhinosinusitis. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;87:111–129. doi: 10.1159/000087639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L.C., Zarrin A.A. The production and regulation of IgE by the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:247–259. doi: 10.1038/nri3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann R., Rabaszowski M., Stenin I., Tilgner L., Scheckenbach K., Wiltfang J., Schipper J., Chaker A., Wagenmann M. Comparison of the nasal release of IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, CCL13/MCP-4, and CCL26/eotaxin-3 in allergic rhinitis during season and after allergen challenge. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:266–272. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenyon N.J., Kelly E.A., Jarjour N.N. Enhanced cytokine generation by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in allergic and asthma subjects. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:115–120. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni R., Behboudi S., Sharif S. Insights into the role of Toll-like receptors in modulation of T cell responses. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:141–152. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand P., Singh B., Jaggi A.S., Singh N. Mast cells: an expanding pathophysiological role from allergy to other disorders. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385:657–670. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin K., Janson C., Bystrom J. Role of eosinophil granulocytes in allergic airway inflammation endotypes. Scand J Immunol. 2016;84:75–85. doi: 10.1111/sji.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu J.T. helper 2 (Th2) cell differentiation, type 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) development and regulation of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 production. Cytokine. 2015;75:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricketti P.A., Alandijani S., Lin C.H., Casale T.B. Investigational new drugs for allergic rhinitis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:279–292. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1290079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attele A.S., Wu J.A., Yuan C.S. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shergis J.L., Zhang A.L., Zhou W., Xue C.C. Panax ginseng in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. Phytother Res. 2013;27:949–965. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ru W., Wang D., Xu Y., He X., Sun Y.E., Qian L., Zhou X., Qin Y. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of Panax ginseng (C. A. Mey.) Drug Discov Ther. 2015;9:23–32. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2015.01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D.H. Chemical diversity of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquifolium, and Panax notoginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:1–15. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin Y.W., Kim D.H. Antipruritic effect of ginsenoside rb1 and compound k in scratching behavior mouse models. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;99:83–88. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choo M.K., Park E.K., Han M.J., Kim D.H. Antiallergic activity of ginseng and its ginsenosides. Planta Med. 2003;69:518–522. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D.H. Gut microbiota-mediated pharmacokinetics of ginseng saponins. J Ginseng Res. 2018;42:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D.H. Metabolism of ginsenosides to bioactive compounds by intestinal microflora and its industrial application. J Ginseng Res. 2009;33:165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heo J.H., Lee S.T., Chu K., Oh M.J., Park H.J., Shim J.Y., Kim M. Heat-processed ginseng enhances the cognitive function in patients with moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Nutr Neurosci. 2012;15:278–282. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim C.M., Yi S.J., Cho I.J., Ku S.K. Red-koji fermented red ginseng ameliorates high fat diet-induced metabolic disorders in mice. Nutrients. 2013;5:4316–4332. doi: 10.3390/nu5114316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung J.W., Kang H.R., Ji G.E., Park M.S., Song W.J., Kim M.H., Kwon J.W., Kim T.W., Park H.W., Cho S.H. Therapeutic effects of fermented red ginseng in allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:103–110. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K.A., Yoo H.H., Gu W., Yu D.H., Jin M.J., Choi H.L., Yuan K., Guerin-Deremaux L., Kim D.H. Effect of a soluble prebiotic fiber, NUTRIOSE, on the absorption of ginsenoside Rd in rats orally administered ginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2014;38:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J.K., Kim J.Y., Jang S.E., Choi M.S., Jang H.M., Yoo H.Y., Kim D.H. Fermented red ginseng alleviates cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis in mice by regulating macrophage activation and T cell differentiation. Am J Chin Med. 2018;46:1–19. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X18500945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bae E.A., Park S.Y., Kim D.H. Constitutive beta-glucosidases hydrolyzing ginsenoside Rb1 and Rb2 from human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:1481–1485. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H.J., Shin C.K., Hsu H.Y., Chiang W. Mast cell dependent allergic responses are inhibited by ethanolic extract of adlay (Coix lachrymal-jobi L. var. ma-yuen Stepf) testa. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:2596–2601. doi: 10.1021/jf904356q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh H.A., Seo J.Y., Jeong H.J., Kim H.M. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits the TSLP production in allergic rhinitis mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2013;35:678–686. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2013.837061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu Z.W., Wang Y.X., Cao Z.W. Neutralization of interleukin-9 ameliorates symptoms of allergic rhinitis by reducing Th2, Th9, and Th17 responses and increasing the Treg response in a murine model. Oncotarget. 2017;8:14314–14324. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim S.M., Kang G.D., Jeong J.J., Choi H.S., Kim D.H. Neomangiferin modulates the Th17/Treg balance and ameliorates colitis in mice. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim S.M., Choi H.S., Kim D.H. The mixture of Anemarrhena asphodeloides and Coptis chinensis attenuates high-fat diet-induced colitis in mice. Am J Chin Med. 2017;45:1033–1046. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X17500550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L., Pi J., Wu J., Zhou H., Cai J., Li T., Liu L. A rapid and sensitive assay based on particle analysis for cell degranulation detection in basophils and mast cells. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim K., Kim Y., Kim H.Y., Ro J.Y., Jeong D. Inhibitory mechanism of anti-allergic peptides in RBL-2H3 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong Y.J., Paeng J.W., Choi D.C., Lee B.J. Effects of Korean red ginseng extracts on airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a murine asthma model. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;30:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim D.Y., Yang W.M. Panax ginseng ameliorates airway inflammation in an ovalbumin-sensitized mouse allergic asthma model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee H.J., Cho S.H. Therapeutic effects of Korean red ginseng extract in a murine model of atopic dermatitis: anti-pruritic and anti-inflammatory mechanism. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:679–687. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babayigit A., Olmez D., Karaman O., Bagriyanik H.A., Yilmaz O., Kivcak B., Erbil G., Uzuner N. Ginseng ameliorates chronic histopathologic changes in a murine model of asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:493–498. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobita K., Yanaka H., Otani H. Anti-allergic effects of Lactobacillus crispatus KT-11 strain on ovalbumin-sensitized BALB/c mice. Animal Sci J. 2010;81:699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung J.H., Kang I.G., Kim D.Y., Hwang Y.J., Kim S.T. The effect of Korean red ginseng on allergic inflammation in a murine model of allergic rhinitis. J Ginseng Res. 2013;37:167–175. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han S.K., Song J.Y., Yun Y.S., Yi S.Y. Ginsan improved Th1 immune response inhibited by gamma radiation. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:343–350. doi: 10.1007/BF02977803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z., Chen A., Sun H., Ye Y., Fang W. Ginsenoside Rd elicits Th1 and Th2 immune responses to ovalbumin in mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee E.J., Ko E., Lee J., Rho S., Ko S., Shin M.K., Min B.I., Hong M.C., Kim S.Y., Bae H. Ginsenoside Rg1 enhances CD4(+) T-cell activities and modulates Th1/Th2 differentiation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takei M., Tachikawa E., Hasegawa H., Lee J.J. Dendritic cells maturation promoted by M1 and M4, end products of steroidal ginseng saponins metabolized in digestive tracts, drive a potent Th1 polarization. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bae E.A., Han M.J., Shin Y.W., Kim D.H. Antiallergic and antipsoriatic effects of Korean red ginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2005;29:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J., Wu H., Wang Q., Chang Y., Liu K., Song S., Yuan P., Fu J., Sun W., Huang Q. Ginsenoside metabolite compound k alleviates adjuvant-induced arthritis by suppressing T cell activation. Inflammation. 2014;37:1608–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9887-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J., Wu H., Wang Q., Chang Y., Liu K., Wei W. Ginsenoside metabolite compound K suppresses T-cell priming via modulation of dendritic cell trafficking and costimulatory signals, resulting in alleviation of collagen-induced arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;353:71–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.220665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bae E.A., Trinh H.T., Yoon H.K., Kim D.H. Compound K, a metabolite of ginsenoside Rb1, inhibits passive cutaneous anaphylaxis reaction in mice. J Ginseng Res. 2009;33:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joh E.H., Lee I.A., Jung I.H., Kim D.H. Ginsenoside Rb1 and its metabolite compound K inhibit IRAK-1 activation--the key step of inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.