Abstract

Background

Panax ginseng Meyer is known as a conventional herbal medicine, and ginsenoside Rg1, a steroid glycoside, is one of its components. Although Rg1 has been proved to have an antiobesity effect, the mechanism of this effect and whether it involves adipose browning have not been elucidated.

Methods

3T3-L1 and subcutaneous white adipocytes from mice were used to access the thermogenic effect of Rg1. Adipose mitochondria and uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression were analyzed by immunofluorescence. Protein level and mRNA of UCP1 were also evaluated by Western blotting and real-time polymerase chain reaction, respectively.

Results

Rg1 dramatically enhanced expression of brown adipocyte–specific markers, such as UCP1 and fatty acid oxidation genes, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1. In addition, it modulated lipid metabolism, activated 5′ adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, and promoted lipid droplet dispersion.

Conclusions

Rg1 increases UCP1 expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in 3T3-L1 and subcutaneous white adipose cells isolated from C57BL/6 mice. We suggest that Rg1 exerts its antiobesity effects by promoting adipocyte browning through activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway.

Keywords: Adipocytes, Browning, Ginsenoside Rg1, Thermogenesis, Uncoupling protein 1

1. Introduction

Excessive body weight is typically due to obesity, which arises because of an imbalance between food intake and energy expenditure [1]. Following economic development and changes in dietary behavior, obesity has become a major epidemic in the world. Furthermore, the higher prevalence of obesity is concerned with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and various types of cancer [2], [3].

A major function of adipose tissue is to control body fat and energy homeostasis. Adipocytes are the most common cell types in adipose depots [4] and occur in white and brown varieties. White adipocytes (WATs) are highly adapted to store excess calories as triglycerides (TGs). Fat accumulation in obesity involves two cellular mechanisms: WAT hypertrophy (cell size increase) and hyperplasia (cell number increase) [5]. This accumulation of WATs and lipids is directly correlated with a greater risk of obesity-related metabolic disease. Conversely, brown adipocytes (BATs) dissipate chemical energy as heat and therefore can defend against diet-induced obesity [6]. This distinctive function of BATs is mediated through their substantial mitochondrial fragments and the expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) [7]. UCP1 promotes uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by causing mitochondrial proton leakage, meaning that the oxidation of lipid and carbohydrate results in the generation of heat. However, brown fat activation was previously considered only to be of quantitative significance for energy expenditure in human infants and small mammals [8], [9].

In 2009, several groups identified brown fat in adult humans by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography analysis. It was confirmed that adults have brown fat deposits in the supraclavicular and neck region that expresses UCP1 and can be induced in response to cold exposure [8], [10]. However, follow-up studies showed that UCP1-positive cells can also accumulate in white fat tissue by cold exposure or stimulation of β3-adrenergic agonists, including catecholamines. This has been termed adipocyte browning, in which WATs are induced to transdifferentiate into brown-like adipocytes [11]. As a deeper understanding of UCP1 induction in white fat has developed through numerous studies, a possible new therapeutic strategy for the obesity-related metabolic disease has emerged [12].

Recent research showed that a variety of dietary molecules, including flavonoids, may have a thermogenic effect, involving the recruitment of beige adipocytes in white fat depots, thereby improving energy expenditure and inhibiting lipid store in mammals [13]. For instance, the potential of capsaicin [14], resveratrol [15], [16], curcumin [17], green tea epigallocatechin gallate [18], and berberine [19] as thermogenic agents has been explored. A browning effect of these bioactive agents has been suggested by the demonstration of greater expression of BAT-enriched marker, such as UCP1, after their administration [13]. However, further research regarding the potential browning effects of nutrients, which may render them attractive for the prevention of metabolic disorders, is still required.

Recent research has also attempted to elucidate an antiobesity effect of ginseng. One of the precious medical plants is Panax ginseng Meyer [20], [21]. It is considered that ginseng has beneficial effects on metabolism and improves health [22], [23]. The valuable ingredients accountable for the effects of ginseng are ginsenosides, a class of steroidal glycosides [24]. Of the ginsenosides, Rg1 is a bioactive component in P. ginseng and is a triterpene saponin that has a rigid steroidal skeleton with sugar moieties [25]. Numerous potential therapeutic effects of ginsenoside Rg1 have been explored. For example, Rg1 suppresses diet-induced obesity and ameliorates its insulin resistance by inducing the 5′ adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity [22]. It also has a protective effect against alcoholic hepatitis through modulation of the nuclear factor-κB pathway [26], prevents skeletal muscle atrophy by regulating serine-threonine protein kinase (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin/forkhead box O (FoxO) signaling [24], and protects against oxidative stress by inhibiting the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway in H9c2 cells [27]. Inhibitory effects of Rg1 on apoptosis have also been identified, which it achieves by activating AMPK/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling and autophagy, and potential antiproliferative effects on lung and liver cancer have also been investigated [28], [29], [30]. An antidiabetic effect of Rg1 has been evaluated in high-fat diet–fed mice [22], and recently, it was reported that dietary Rg1 attenuates fat accumulation and ameliorates obesity-related metabolic disease [31].

Previous our research [32] has also demonstrated an effect of Rg1 to suppress TG accumulation in 3T3-L1 and high-fat diet–induced obesity model of zebrafish. However, the effect of Rg1 to activate browning mechanism in WATs has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the aim of the present research was to determine whether Rg1 can induce a brown fat-like phenotype using two different cellular models: 3T3-L1 and subcutaneous white adipocytes (scWATs) isolated from C57BL/6 mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Rg1 (≥98% purity, Lot number 14052305) was purchased from Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd (Chengdu, China). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), bovine calf serum, fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), penicillin and streptomycin (P/S), insulin, and trypsin EDTA were purchased from Gibco (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Dexamethasone (DEX), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), triiodothyronine (T3), rosiglitazone (Rsg), oil red O (ORO), Hoechst 33342, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails II and III were provided by Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dorsomorphin dihydrochloride (compound C) and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (CL-173; Manassas, VA, USA). Antibodies against AMPKα, p-AMPKα, PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16), Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) co-activator (PGC1α), and aP2 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα), C/EBPβ, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), PPARα, PPARγ, p-hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Antibodies against PPARδ and UCP1 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Other materials were purchased from Sigma.

2.2. Cell culture and differentiation

DMEM medium containing 10% bovine calf serum, 1% P/S, and 3.7 g/L of sodium bicarbonate were used for maintaining of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Adipocytes were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and cultured to confluence by replacing the growth medium every 2 d. Initial differentiation of confluent 3T3-L1 can be induced by a 2-d treatment with differentiation medium (1 μM DEX, 0.5 mM IBMX, and 5 μg/mL insulin in DMEM including 10% FBS). Culture medium was then refreshed every 2 d with maintenance medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 5 μg/mL of insulin).

Stromal vascular fractions (SVFs) were obtained from the subcutaneous fat tissue of 5- to 7-week-old male C57BL/6 mice in accordance with a written protocol in journal of visualized experiments [33]. Isolated fat pads were minced and then digested at 37°C in PBS supplemented with 2.4 U/mL of dispase II (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), 1.5 U/mL of collagenase D (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), and 10 mM CaCl2. After 1 h, undigested tissue was removed by filtering using 40-μm cell strainers (SPL Life Science, Switzerland). Filtered SVF cells were then washed in PBS and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min and then resuspended in Glutamax DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. To differentiate, adipocytes were cultured to confluence in SVF culture medium.

After reaching confluence, differentiation into WATs was induced by incubating for 2 d with initial differentiation medium composed of 100 μM indomethacin (Sigma), 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM DEX, and 5 μg/ml of insulin. Subsequently, the medium was refreshed to maintenance medium (DMEM containing 10% FBS and 5 μg/mL of insulin).

Compound Rg1 stock was prepared at 40 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted with differentiation medium to 25, 50, and 100 μM. To promote WAT browning, cells were incubated with differentiation medium containing 10 nM T3 and 1 μM Rsg. Subsequently, after 48 hours, initiation medium was replaced with maintenance medium supplemented with 10 nM T3.

2.3. ORO staining

Adipocytes that had been differentiated for 6–8 days were rinsed with PBS and fixed using 10% formaldehyde at room temperature for an hour. After rinsing again with PBS, 0.5% ORO solution in 6:4 (v/v) isopropanol:water was layered onto differentiated cells for 1 h at room temperature. Stained adipocytes were analyzed by light microscopy, ORO was eluted with isopropanol, and its intensity was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm

2.4. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA preparation and reverse transcription and real-time polymerase chain reaction were carried out to investigate mRNA expression levels. Briefly, mature adipocytes were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 1.5 μg of RNA was converted to cDNA using Maxime RT premix (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). To quantify the expression levels of genes, power SYBR green (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were used. All experiments were carried out in triplicate for each sample, and relative mRNA levels were normalized against 18s rRNA. Oligonucleotide primers used for Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) are marked in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for quantitative real-time PCR in this research

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| ACOX1 | GCACCTTCGAGGGGGAGAACA | GCGCGAACAAGGTCGACAGAA |

| CPT1 | GCTTGGCGGATGTGGTTC | GCTGGAGGTGGCTTTGGT |

| Cyp4A10 | TTCAGAGCCTCCTGGGGGATG | GGAGCAGTGTCAGGGCCACAA |

| Cyp4A14 | ATGCCTGCCAGATTGCTCACG | GGGTGGGTGGCCAGAGCATAG |

| HSL | CATTAGACAGCCGCCGTGCT | TGGGGAGCTCCAGTCGGAAG |

| PPARα | AGGGCCTCCCTCCTACGCTTG | GGGTGGCAGGAAGGGAACAGA |

| 18s | GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG | GGCCTCACTAAACCATCCAA |

ACOX1, acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; Cyp4A10, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10; Cyp4A14, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 14; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

2.5. Western blotting

Samples were prepared in lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. For Western blotting, protein extracts (20 μg) were diluted in 5× sample buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and then boiled for 5 min at 90°C before performing SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). After that, proteins were transferred from polyacrylamide gel to polyvinyl difluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked using 5% nonfat dried milk and rinsed three times with tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST), followed by immunoblotting with primary polyclonal antibody for 6 h. After washing, the membranes were incubated for 2 hours with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in TBST buffer supplemented with 5% nonfat dried milk. Reactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence and using LAS image software (Fuji, New York, NY, USA).

2.6. Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence studies, adipocytes were cultured on 12 × 12 mm poly-L-lysine pretreated slides and then fixed in methanol, followed by rinsing with PBS. The fixed adipocytes were blocked with 1% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST for an hour and incubated with polyclonal anti-UCP1 antibody (1:500 dilution) overnight at 4°C, followed by three rinses. After that, adipocytes were treated with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500 dilution) in blocking solution. To stain mitochondria, MitoTracker Red (1 mM; Cell Signaling Technology) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, the cells were fixed, washed once with PBS, and then immunostained. The nuclei of the fixed cells were stained by using Hoechst. Finally, slides were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade reagent (Life Technologies), and imaging data were obtained by using a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope LSM880 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) combined with Zeiss microscope software ZEN 2012 (Carl Zeiss) and ImageJ software.

2.7. Cell viability test

Adipocytes were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and treated with Rg1 (0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μM) and incubated. After 24 h, 40 μL of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma) was added to each well for measuring cell survival in a quantitative colorimetric assay. After removing the medium, dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μL/well) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals produced by the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. The resulting absorbance at 595 nm was detected using a plate reader (BioTek PowerWave HT; BioTek Instruments Inc. Winooski, VT, USA,).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Protein results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and multiple comparisons were made between groups using one-way analysis of variance (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) with Duncan's multiple range test. Each group is expressed using “a, b, c, and d”. Real-time polymerase chain reaction results were also presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and Student t test was used to determine p values. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Rg1 downregulates adipogenesis markers in scWATs and reduces lipogenesis

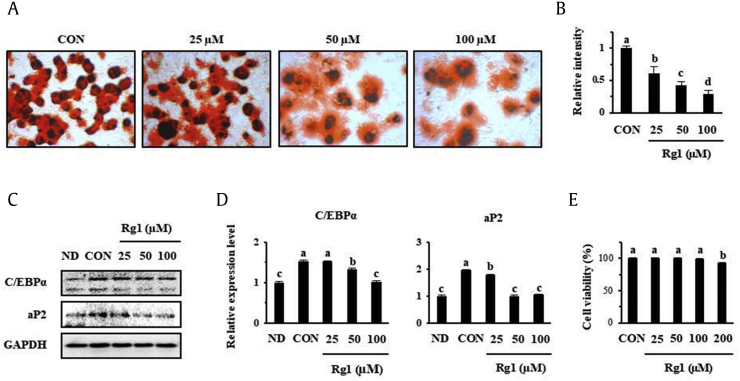

Rg1, a bioactive constituent of P. ginseng, has been shown to reduce lipid metabolism in 3T3-L1 [32] because Rg1 suppressed the expression of adipogenesis markers, such as C/EBPα and aP2, in a dose-dependent manner. Here, we assessed whether Rg1 affects cellular fat metabolism in primary scWATs from mice. ORO staining showed that the fat accumulation in scWATs was considerably decreased by Rg1, as indicated in Fig. 1A and B. Western blot analysis revealed that C/EBPα and aP2 expression were both lower in scWATs treated with 50 μM Rg1 than in control cells (Fig. 1C and D). Furthermore, when the viability of scWATs treated with Rg1 at concentrations of 25–200 μM was tested, no cytotoxicity was demonstrated up to 100 μM, but 200 μM Rg1 had a slight toxic effect, as shown in Fig. 1E.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Rg1 on fat accumulation and the expression of key adipogenic factors in scWAT cells. oil red O staining was used to assess adipocyte differentiation after 8 days in the presence or absence of Rg1. (A) Photomicrographs of cells. (B) Intensity-densitometric analysis. (C–D) Concentration-dependent effect of Rg1 on the expression of adipogenesis markers, analyzed by Western blotting. (E) Viability of scWATs, evaluated using an MTT assay. These data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of four replicates. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; MTT, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; ND, undifferentiated; scWATs, subcutaneous white adipocytes.

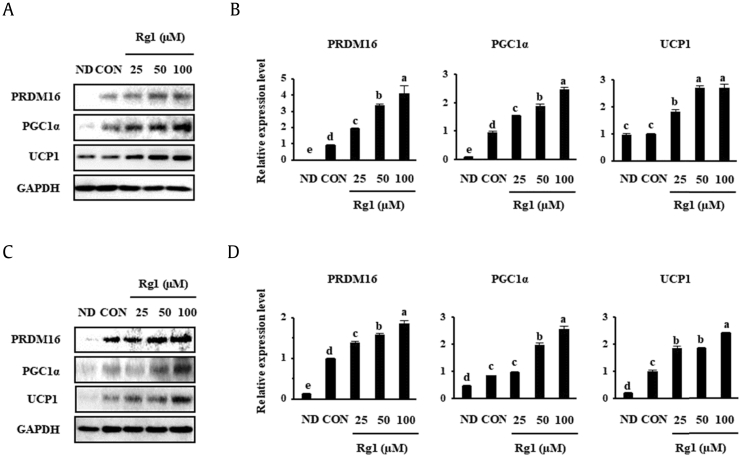

3.2. Rg1 enhances the expression of BAT markers in scWATs and 3T3-L1

Browning of WATs may contribute significantly to whole-body thermogenesis. The transcription factor PRDM16 is a key mediator of brown fat cell differentiation, and PGC1α is an essential factor for the regulation of mitochondrial function [7]. UCP1 is required for thermogenesis, uncoupling respiration from energy generation and resulting in the liberation of heat [34]. To evaluate the browning effect of Rg1, scWATs and 3T3-L1 that had been induced to differentiate were treated with various concentrations of Rg1 (25, 50, or 100 μM), and then the expression of the described biomarkers was measured by Western blotting. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows that Rg1 treatment significantly increased the expression of the BAT markers that are important for adipose thermogenesis, including PRDM16, PGC1α, and UCP1, in a dose-dependent fashion.

Fig. 2.

Dose-dependent effect of Rg1 on the expression of BAT-specific markers. (A, C) Rg1 (25, 50, or 100 μM) was added to scWAT and 3T3-L1 (B, D), which was followed by the measurement of protein expression by Western blotting. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. There was a statistically significant difference between the control and Rg1-treated groups (p < 0.05).

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BAT, brown adipocyte; CON, control; ND, undifferentiated; PGC1α, PPARγ co-activator; PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

We used 50 μM Rg1 for subsequent cell treatments because it was effective at reducing lipid accumulation, as shown in Fig. 1.

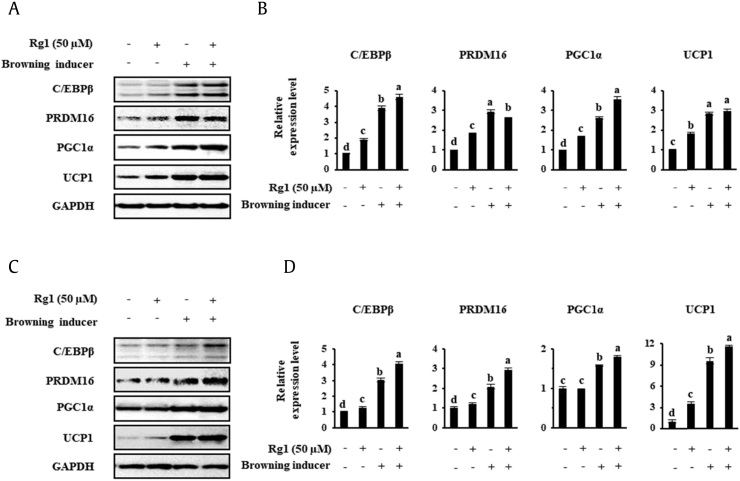

3.3. WATs treated with Rg1 demonstrate characteristics of BATs, including UCP1 expression and higher mitochondrial activity

To compare the browning effect of the well-known inducers T3 and Rsg with that of Rg1, we studied the expression levels of BAT genes in cells treated with each. T3 is a thyroid hormone that not only regulates thermogenesis but also adjusts metabolism and energy balance. It activates brown fat thermogenesis by stimulating norepinephrine release and by increasing UCP1 gene expression [35]. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrated that T3 similarly promotes the browning of scWAT [36], [37]. In addition, Rsg, an antidiabetic PPARγ ligand, has been shown to promote browning in WATs as a secondary effect, and 1 μM has been shown to be effective for this purpose in inguinal WATs [38], [39], [40]. Here, scWATs and 3T3-L1 were incubated with 50 nM T3 and 1 μM Rsg to induce browning, with or without 50 μM Rg1. The data in Fig. 3 demonstrate that treatment with T3 and Rsg resulted in the upregulation of several proteins (C/EBPβ, PRDM16, PGC1α, and UCP1) versus the vehicle control in both cell types. As can be seen in the final scWAT lane in Fig. 3, Rg1 had an additive effect to the other substances on target gene expression, with the sole exception of PRDM16, but it had an additive effect on four marker's expression in 3T3-L1.

Fig. 3.

Known inducers of browning and Rg1 induce the expression of browning markers in scWATsand 3T3-L1. Browning was induced by the treatment of cells with 50 nM T3 and 1 μM rosiglitazone. (A, C) scWAT were treated with 50 μM Rg1, and the protein expression levels of BAT-specific markers were measured by Western blotting. (B, D) Quantitative data, representing the mean and standard deviation of six replicates. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BAT, brown adipocyte; PGC1α, PPARγ co-activator; PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; scWATs, subcutaneous white adipocytes; T3, triiodothyronine; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

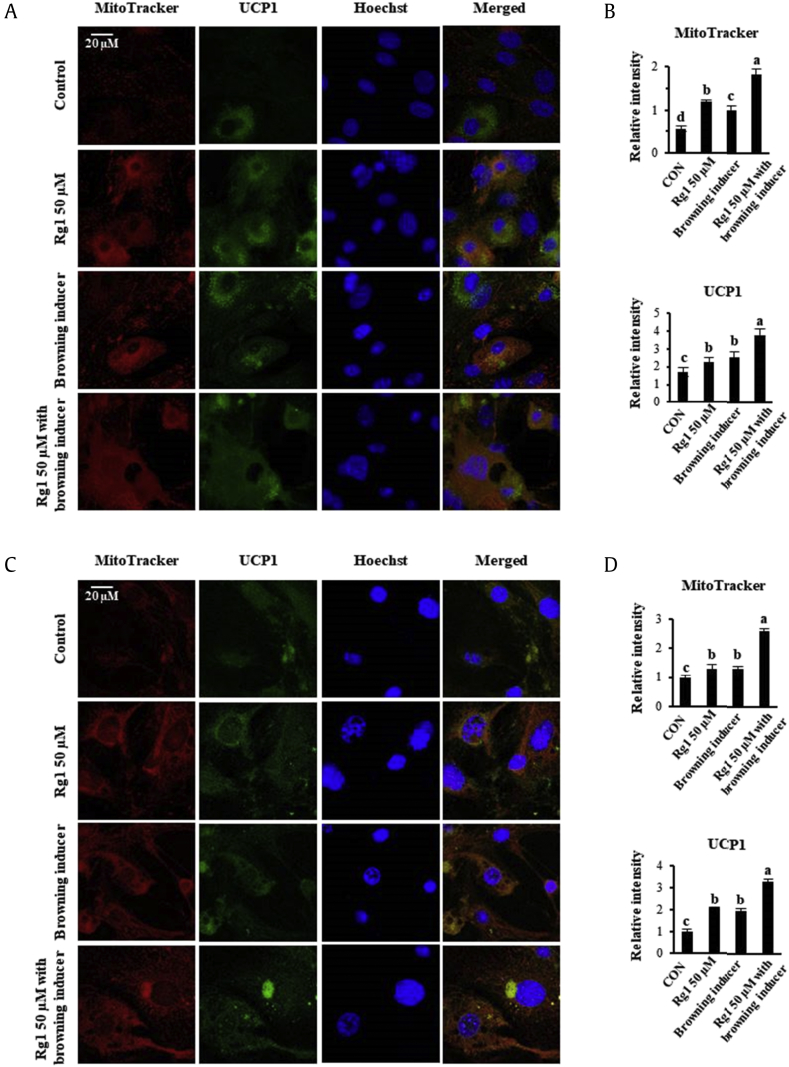

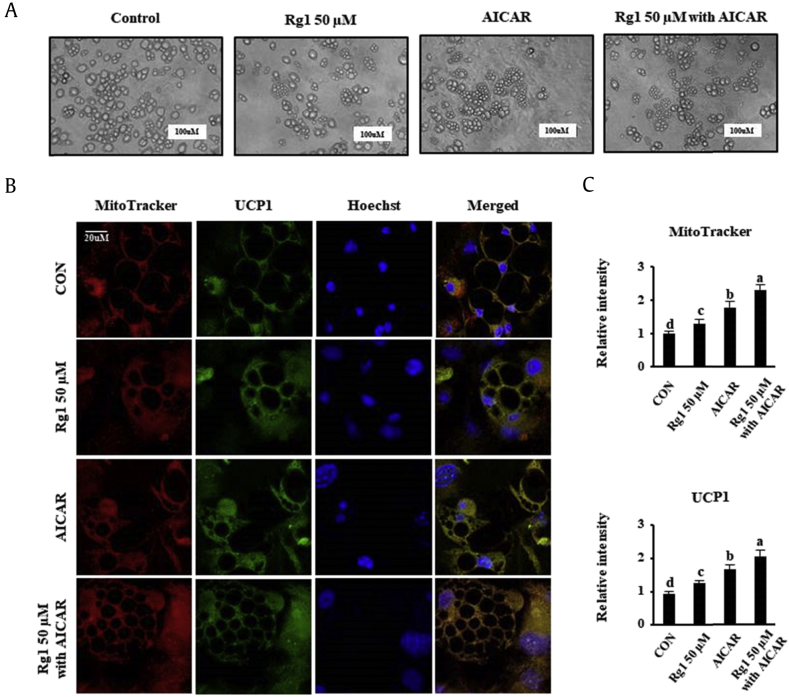

It has been known for many years that the increase in metabolic rate associated with UCP1 induction is accompanied by greater mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in WATs. The mitochondria in BATs are much more numerous and bigger than those in WATs, indicative of the contrasting metabolic roles of the two adipose types [2]. To determine whether Rg1 treatment enhances UCP1 activity and mitochondrial biogenesis, we assessed these parameters by immunofluorescence, as shown in Fig. 4. Differentiated adipocytes were stained with MitoTracker Red, a red fluorescent dye that specifically binds to mitochondria, and then incubated with UCP1 antibody conjugated with FITC (green). We observed significantly more intense red and green staining in the cytoplasm of Rg1-treated scWATs and 3T3-L1, and UCP1-positive adipocytes also showed colocalization of mitochondria and UCP1 expression in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, the addition of Rg1 enhanced UCP1 expression and mitochondrial mass above that of the known browning inducers in both the types of adipocytes. Taking these data together, Rg1 induces the browning of WATs by regulating mitochondrial function and UCP1 expression.

Fig. 4.

Rg1 treatment enhances mitochondrial activity and expression of UCP1. (A) Rg1-treated scWAT and (C) 3T3-L1 adipocytes were stained with MitoTracker Red and immunostained for UCP1. (B, D) Quantitative data for MitoTracker Red and UCP1 staining intensity in scWAT and 3T3-L1 adipocytes, respectively. Immunofluorescent images were captured at ×800 magnification. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three replicates and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; PGC1α, PPARγ co-activator; PPARγ, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; scWATs, subcutaneous white adipocytes; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

3.4. Rg1 modulates lipid metabolism by inducing FAO in WATs

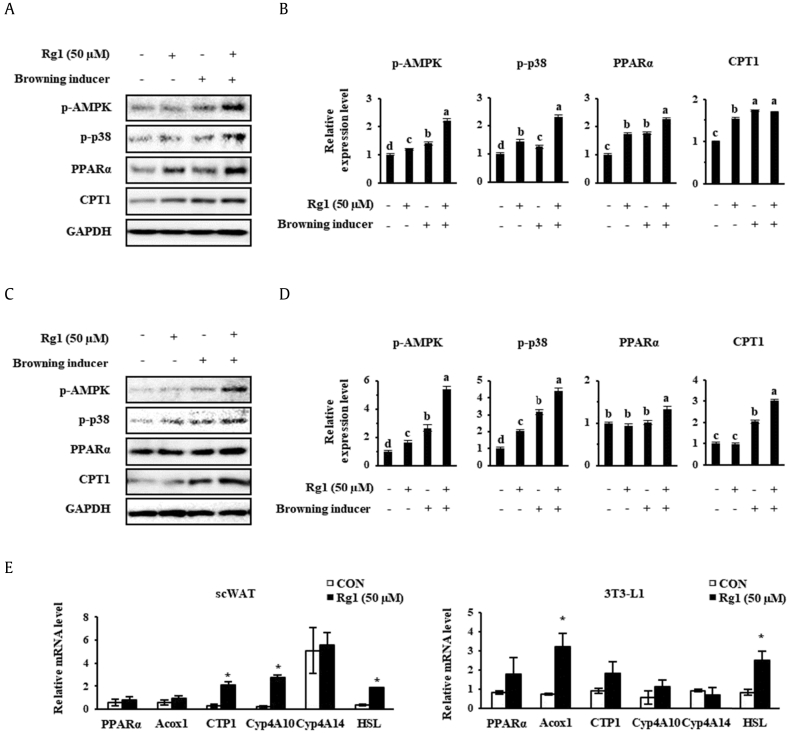

Fatty acids released from lipolysis can be oxidized in the mitochondria of adipose cells. This FAO is crucial for mitochondrial bioenergetics and the thermogenic program involving UCP1. BATs contain plentiful mitochondria and require the undertaking of high levels of FAO to liberate sufficient heat [41], [42]. Because significant increases in mitochondrial activity were demonstrated in Rg1-treated cells, we explored whether Rg1 can change fat mass in scWATs and 3T3-L1. As shown in Fig. 5A–D, Western blot analysis showed that phosphorylated AMPK, phosphorylated p38, PPARα, and CPT1 were upregulated after treatment with Rg1 and/or known browning inducers. The ectopic expression of these FAO genes and UCP1 in WATs is consistent with the acquisition of BAT features by these cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Rg1 on the expression of markers of fatty acid oxidation in adipocytes. (A, C) Western blots for p-AMPK, p-p38, PPARα, and CPT1 in scWAT and 3T3-L1s, respectively, and (B, D) their quantitation. Cells were treated with 50 nM T3 and 1 μM rosiglitazone. (E) Relative mRNA expression of fatty acid oxidation genes was measured using real-time PCR and normalized to 18s rRNA expression. These data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of six replicates. Protein data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05. mRNA data were analyzed using Student t test, and values were considered significant when *p < 0.05.

ACOX1, acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1; AMP, 5′ adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; Cyp4A10, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10; Cyp4A14, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 14; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; T3, triiodothyronine.

Then, the mRNA levels of PPARα, peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX1); CPT1; cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10 (Cyp4A10); cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 14 (Cyp4A14); and HSL were measured. This showed that Rg1 had an additive effect to the known browning inducers on the expression of PPARα, ACOX1, and CPT1, which are all involved in FAO. Rg1 treatment also increased the mRNA levels of Cyp4A10 and Cyp4A14, which are PPARα-responsive genes involved in microsomal oxidation. Finally, HSL, the enzyme that performs the second step in TG lipolysis, was upregulated by Rg1 treatment in both the cell types. This result is consistent with the effects of Rg1 on the FAO gene expressions because HSL can also promote FAO by helping provide free fatty acids for this purpose.

3.5. Rg1 treatment regulates lipid droplet size and browning, potentially by increasing AMPK phosphorylation

Finally, we investigated whether AMPK was essential for the promotion of UCP1 expression by Rg1. AMPK is an important cellular energy sensor that helps maintain metabolic homeostasis [43]. A number of previous studies [19], [22], [44], [45], [46] showed that the induction of AMPK phosphorylation by AICAR leads to the appearance of BAT properties in 3T3-L1. Therefore, we evaluated scWAT morphology in the four treatment groups during cell differentiation, over 14–16 days. Interestingly, the number of small lipid droplets was increased by 50 μM Rg1 and 10 μM AICAR treatment, as shown in Fig. 6A, consistent with the lower ORO staining as indicated in Fig. 1A. The immunofluorescence data shown in Fig. 6B and C demonstrate that Rg1 efficiently browns WATs alone and has an additive effect to that of AICAR because it upregulates UCP1 expression and mitochondrial biogenesis. In addition, we also observed that the rounded unstained parts of the cells were reduced in size after Rg1 or AICAR treatment. These findings imply that the size of lipid droplets in scWATs can be reduced by Rg1 treatment, possibly through AMPK activation.

Fig. 6.

Effects of AICAR on lipid droplet morphology and mitochondrial biogenesis in scWATs. (A) Morphology was evaluated by optical microscopy (×400). Adipocytes were differentiated for 16 days. The scale bar represents 100 μM. (C) Representation of the mitochondrial activity, UCP1 expression, and lipid droplet size in differentiated scWATs, (B, D) Quantitative data for MitoTracker Red and UCP1 immunofluorescence staining intensity. These data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of triplicates. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; ANOVA, analysis of variance; CON, control; scWATs, subcutaneous white adipocytes; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

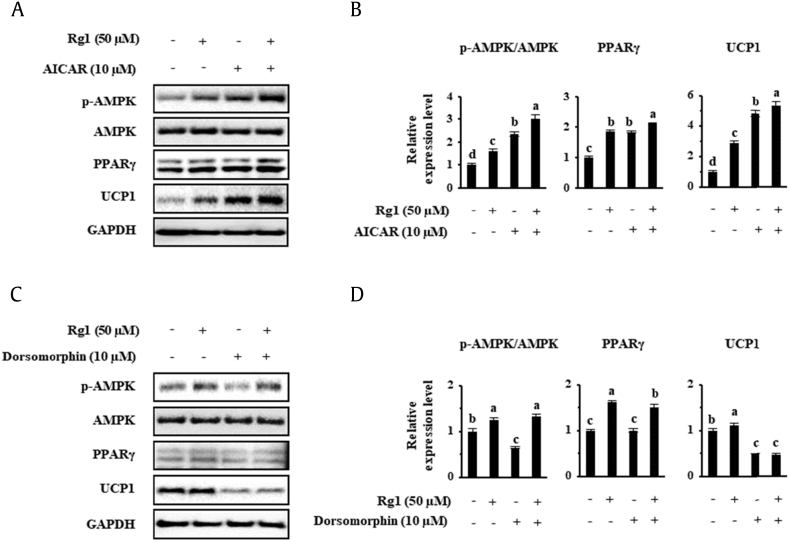

Then, to further examine the mechanism of these browning effects of Rg1, we measured the protein expression of phosphorylated AMPK. We used 10 μM AICAR and 10 μM dorsomorphin as an activator and an inhibitor of AMPK, respectively, choosing the concentrations to be used based on a previous study of lipid accumulation in adipocytes and mice [47]. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, AMPK phosphorylation was increased by AICAR treatment, and UCP1 expression was upregulated in scWATs. Rg1 treatment also increased AMPK phosphorylation (Thr172) to a similar amount to that achieved using AICAR. Moreover, an additive effect of the two treatments on AMPK activation was observed. By contrast, the abolition of AMPK activation by dorsomorphin resulted in a reduction of PPARγ and UCP1 protein levels, as indicated in Fig. 7C and D. Rg1 partially ameliorated the effect of the AMPK inhibitor on phosphorylation, but PPARγ and UCP1 levels remained below their levels in the control cells. In summary, our results show that AMPK activation might be crucial to the browning effect of Rg1, including the induction of UCP1 protein level, in both the types of WATs.

Fig. 7.

Effects of AICAR and dorsomorphin on the expression of UCP1 in scWAT. To assess the importance of AMPK activation, adipocytes were differentiated in the presence of AICAR or dorsomorphin. 3T3-L1 cells were treated with 10 μM AICAR or 10 μM dorsomorphin, and the effects on specific protein expression levels were investigated using Western blotting. These data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of triplicates. Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan's test. Values with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; AMP, 5′ adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ANOVA, analysis of variance; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

Overall, we showed that Rg1 has a browning effect in scWAT and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Because Rg1 treatment modulates the protein expression level of UCP1, this finding may be valuable in the improvement of new therapies for the obesity treatment.

4. Discussion

Adipose tissue is an essential organ that is related with the modulation of energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity [48]. It is consisted of various cell types, which are WATs and BATs. Each of these types of adipocyte has unique cell-autonomous functions, and they differ at molecular and morphological levels [49]. WAT principally stores lipid in the form of TGs, thereby acting as a repository of surplus energy in the body. Conversely, BAT utilizes stored lipid for nonshivering thermogenesis, involving β-oxidation and uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. Consistent with this function, the cytoplasm of BATs contains numerous mitochondria and small lipid bodies [50]. Thus, enhancing BAT activity or transition to brown-like cells of WATs can improve energy expenditure and in turn has the potential to ameliorate or prevent the development of metabolic diseases that are linked with obesity.

P. ginseng has been the most extensively used alternative medicine for more than 1,000 years. Ginsenosides represent major components of ginseng, which have beneficial antioxidant and antiinflammatory properties [51]. A previous research demonstrated that one of these, Rg1, inhibits the early step of adipose cell differentiation, such that it can suppress fat accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Furthermore, protein expression of the adipogenesis markers such as C/EBPα and aP2 was reduced in a dose-dependent fashion. However, this previous study did not establish whether browning of these WATs might be effective in the prevention of obesity [32].

Thus, in the present study, we aimed to determine whether Rg1 might be capable of inducing transdifferentiation of scWAT and 3T3-L1 cells, an approach that might be promising for obesity treatment in the future. To this end, the expression levels of key transcripts involved in the browning process were measured in both adipocytes. Rg1 treatment induced dose-dependent upregulation in BAT-enriched marker levels, including PRDM16, PGC1α, and UCP1, in both the types of adipocytes. In addition, we compared the browning effect of Rg1 with that of the combination of T3 and Rsg, known inducers of browning, in mature differentiated adipocytes. Rg1 alone improved the UCP1 level, the most important marker in BATs, and this was accompanied by upregulation of transcription factors that are induced during the differentiation of BATs (C/EBPβ, PRDM16, and PGC1α). In addition, both the types of adipocyte became more sensitive to the effects of the known browning inducers, expressing higher levels of BAT markers than cells treated with Rg1 alone (by >4% and >21% in scWAT and 3T3-L1, respectively). These data determined that Rg1 treatment enhanced UCP1 protein level in WATs in a cell-autonomous manner. However, there was no significant difference in the mRNA level of UCP1 among the cells (data not shown). Although the assessment of the degree of browning of WATs tends to be based on UCP1 protein level, mRNA level of UCP1 on its own does not essentially lead to an improvement in the metabolic rate [52].

The process of thermogenesis in the adipocyte generate principally in mitochondria, which contain BAT-specific inner membrane protein UCP1 [2], implying that mitochondrial activity is important for fat browning. Here, we showed by immunofluorescence that Rg1 increases mitochondrial activity and UCP1 expression. To better understand the significance of these effects, we assessed the ability of Rg1 with that of two known inducers of browning and showed that Rg1 has an additive effect to these on mitochondrial biogenesis and UCP1 activity in both white adipose cells. We also demonstrated greater protein level of PGC1α, one of the major modulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, in these cells, which represents further evidence of the acquisition of the features of BATs.

According to recent findings [53], [54], enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis can be induced by norepinephrine release caused by agents such as T3. Rsg, a known PPARγ agonist, also suggests the upregulation of key proteins involved in FAO, which is vital for the function of UCP1. We showed that Rg1 can also induce a BAT-like phenotype in adipocytes, which involves greater phosphorylation of AMPK and p38, and expression of PPARα and CPT1, all of which are important for mitochondrial activity and FAO in BATs. In addition, we found large increases in mRNA expression of ACOX1, Cyp4A10, and Cyp4A14. ACOX1 is an initial enzyme of the peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation pathway, whereas Cyp4A10 and Cyp4A14 are microsomal fatty acid ω-hydroxylases. These genes are upregulated by PPARα and convert fatty acids into coenzyme A esters, which are transported across the mitochondrial membrane through the action of CPT1 and undergo β-oxidation within [55]. Thus, these FAO genes both contributed to mitochondrial bioenergetics and act as biophysical activators of uncoupling [56]. Interestingly, the mRNA encoding the lipolytic enzyme HSL was also markedly upregulated by Rg1 in both the types of cells. HSL is one of the enzymes in lipolysis, converting diacylglycerol to monoacylglycerol and fatty acids, and is activated by β-adrenergic signaling. The free fatty acids generated in the cytoplasm can be transported across mitochondrial, microsomal, and peroxisomal membranes to be oxidized [57], [58]. To sum up, these findings indicate that Rg1 induces the browning of WATs through increasing of lipolysis and FAO.

During the differentiation of scWATs for 14–16 days, Rg1 treatment has a significant effect on the appearance of the cells. As shown in Fig. 6, the fat droplets in the cells become much smaller than usual, more like those in BATs. Interestingly, ectopic expression of UCP1 in scWATs was found to be concentrated around these lipid droplets using MitoTracker Red. Our data suggest that these multilocular lipid droplets can rapidly provide fatty acids as a fuel for mitochondrial activation.

AMPK is known as an important metabolic regulator that induces thermogenesis, which is dysregulated in obesity. Substantially, AMPK modulates fatty acid metabolism in adipose tissue, promoting FAO by CPT1 activation. In addition, because AMPK regulates mitochondrial biogenesis by activating UCP1, it is considered a key protein concerned with BAT differentiation [59]. To further investigate if the AMPK acts in the Rg1-treated browning mechanism, we stimulated cells with AICAR and dorsomorphin, an activator and an inhibitor of AMPK, respectively. Rg1 treatment leads to greater phosphorylation of AMPK, which suggests that the browning effects of Rg1 are coordinated through AMPK activation. However, Rg1-stimulated UCP1 induction was not observed in the presence of dorsomorphin, and the abolition of UCP1 expression on PPARγ inhibition further implies that Rg1 has its effects at least in part via the AMPK pathway. According to several studies [40], [60], PPARγ promotes adipogenesis in BATs, which can express UCP1. Consistent with this, imaging of scWATs treated with dorsomorphin showed that their differentiation was impaired (data not shown). Thus, our data suggest that Rg1 induces BAT differentiation by activating the AMPK signaling pathway and thus upregulating mitochondrial activity.

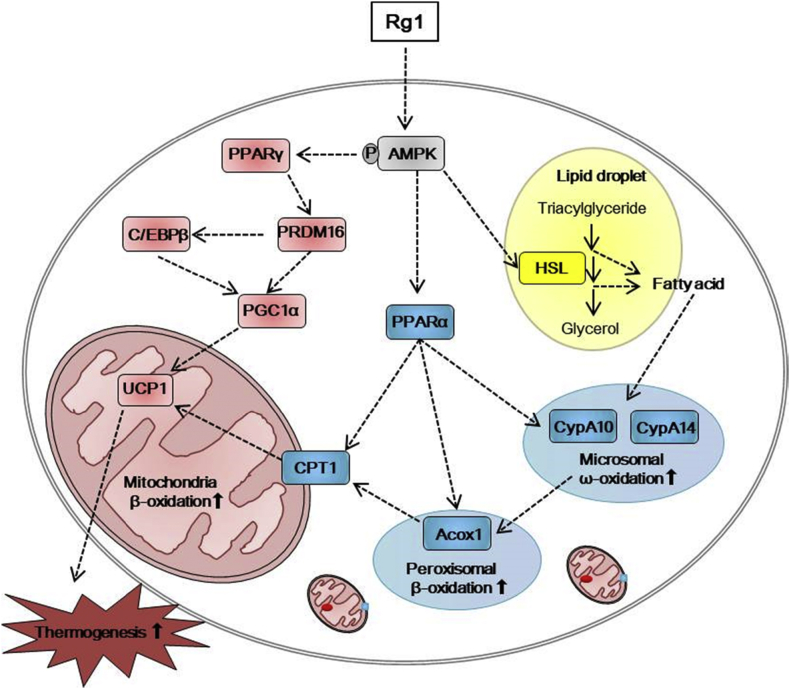

In conclusion, Rg1 induces BAT-like differentiation of adipocytes and thermogenic activation, a process that also involves the upregulation of FAO (Fig. 8). During Rg1-stimulated adipocyte differentiation, AMPK is activated, lipid droplets take on a form typical of brown adipocytes, UCP1 expression is induced, and mitochondrial activity increases. Therefore, we suggest that Rg1-induced UCP1 activation in adipocytes have prospective therapeutic value for obesity suppression and associated metabolic disease [12].

Fig. 8.

Suggested mechanisms for the induction of browning by Rg1. Rg1 induces a brown fat-like phenotype and lipid metabolism through AMPK activation. → indicates stimulation, yellow indicates the hydrolysis pathway, blue indicates the fatty acid oxidation pathway, and pink indicates the thermogenesis pathway.

ACOX1, acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1; AMP, 5′ adenosine monophosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; Cyp4A10, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10; Cyp4A14, cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 14; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; PGC1α, PPARγ co-activator; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1A09917209). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hill J.O., Wyatt H.R., Peters J.C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:126–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cedikova M., Kripnerova M., Dvorakova J., Pitule P., Grundmanova M., Babuska V., Mullerova D., Kuncova J. Mitochondria in white, brown, and beige adipocytes. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:6067349. doi: 10.1155/2016/6067349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen P., Levy J.D., Zhang Y., Frontini A., Kolodin D.P., Svensson K.J., Lo J.C., Zeng X., Ye L., Khandekar M.J. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell. 2014;156:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo L., Liu M. Adipose tissue in control of metabolism. J Endocrinol. 2016;231:R77–R99. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jo J., Gavrilova O., Pack S., Jou W., Mullen S., Sumner A.E., Cushman S.W., Periwal V. Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia: dynamics of adipose tissue growth. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seale P., Conroe H.M., Estall J., Kajimura S., Frontini A., Ishibashi J., Cohen P., Cinti S., Spiegelman B.M. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:96–105. doi: 10.1172/JCI44271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsen M., Raschke S., Tennagels N., Schwahn U., Jelenik T., Roden M., Romacho T., Eckel J. BMP4 and BMP7 induce the white-to-brown transition of primary human adipose stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C431–C440. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00290.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P., Spiegelman B.M., Brown, Fat Beige. Molecular parts of a thermogenic machine. Diabetes. 2015;64:2346–2351. doi: 10.2337/db15-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi J.H., Kim S.W., Yu R., Yun J.W. Monoterpene phenolic compound thymol promotes browning of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:2329–2341. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J., Bostrom P., Sparks L.M., Ye L., Choi J.H., Giang A.H., Khandekar M., Virtanen K.A., Nuutila P., Schaart G. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiang L., Wang L., Kon N., Zhao W., Lee S., Zhang Y., Rosenbaum M., Zhao Y., Gu W., Farmer S.R. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Ppargamma. Cell. 2012;150:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H., Liu L., Lin J.Z., Aprahamian T.R., Farmer S.R. Browning of white adipose tissue with roscovitine induces a distinct population of UCP1(+) adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2016;24:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okla M., Kim J., Koehler K., Chung S. Dietary factors promoting Brown and beige fat development and thermogenesis. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:473–483. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoneshiro T., Aita S., Kawai Y., Iwanaga T., Saito M. Nonpungent capsaicin analogs (capsinoids) increase energy expenditure through the activation of brown adipose tissue in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:845–850. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrade J.M., Frade A.C., Guimaraes J.B., Freitas K.M., Lopes M.T., Guimaraes A.L., de Paula A.M., Coimbra C.C., Santos S.H. Resveratrol increases brown adipose tissue thermogenesis markers by increasing SIRT1 and energy expenditure and decreasing fat accumulation in adipose tissue of mice fed a standard diet. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:1503–1510. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagouge M., Argmann C., Gerhart-Hines Z., Meziane H., Lerin C., Daussin F., Messadeq N., Milne J., Lambert P., Elliott P. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lone J., Choi J.H., Kim S.W., Yun J.W. Curcumin induces brown fat-like phenotype in 3T3-L1 and primary white adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;27:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura S., Ichinose T., Jinde M., Kawashima Y., Tachiyashiki K., Imaizumi K. Tea catechins enhance the mRNA expression of uncoupling protein 1 in rat brown adipose tissue. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z., Zhang H., Li B., Meng X., Wang J., Zhang Y., Yao S., Ma Q., Jin L., Yang J. Berberine activates thermogenesis in white and brown adipose tissue. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5493. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung K.W., Wong A.S. Pharmacology of ginsenosides: a literature review. Chin Med. 2010;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun T.K. Experimental and epidemiological evidence of the cancer-preventive effects of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S71–S81. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J.B., Zhang R., Han X., Piao C.L. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits dietary-induced obesity and improves obesity-related glucose metabolic disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2018;51:e7139. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20177139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim S., Yoon J.W., Choi S.H., Cho B.J., Kim J.T., Chang H.S., Park H.S., Park K.S., Lee H.K., Kim Y.B. Effect of ginsam, a vinegar extract from Panax ginseng, on body weight and glucose homeostasis in an obese insulin-resistant rat model. Metabolism. 2009;58:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F., Li X., Peng X., Sun L., Jia S., Wang P., Ma S., Zhao H., Yu Q., Huo H. Ginsenoside Rg1 prevents starvation-induced muscle protein degradation via regulation of AKT/mTOR/FoxO signaling in C2C12 myotubes. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:1241–1247. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du J., Cheng B., Zhu X., Ling C. Ginsenoside Rg1, a novel glucocorticoid receptor agonist of plant origin, maintains glucocorticoid efficacy with reduced side effects. J Immunol. 2011;187:942–950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J., Yang C., Zhang S., Liu S., Zhao L., Luo H., Chen Y., Huang W. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits inflammatory responses via modulation of the nuclear factorkappaB pathway and inhibition of inflammasome activation in alcoholic hepatitis. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:899–907. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q., Xiang Y., Chen Y., Tang Y., Zhang Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling and inhibition of JNK. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:21–37. doi: 10.1159/000484578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang P., Ling L., Sun W., Yang J., Zhang L., Chang G., Guo J., Sun J., Sun L., Lu D. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits apoptosis by increasing autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR signaling in serum deprivation macrophages. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2018;50:144–155. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmx136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee D.G., Jang S.I., Kim Y.R., Yang K.E., Yoon S.J., Lee Z.W., An H.J., Jang I.S., Choi J.S., Yoo H.S. Anti-proliferative effects of ginsenosides extracted from mountain ginseng on lung cancer. Chin J Integr Med. 2016;22:344–352. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu M., Yu X., Guo D., Yu B., Li L., Liao Q., Xing R. Ginsenoside Rg1 attenuates invasion and migration by inhibiting transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition in HepG2 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:3167–3173. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q., Zhang F.G., Zhang W.S., Pan A., Yang Y.L., Liu J.F., Li P., Liu B.L., Qi L.W. Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits glucagon-induced hepatic gluconeogenesis through Akt-FoxO1 interaction. Theranostics. 2017;7:4001–4012. doi: 10.7150/thno.18788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh E.J., Kim K.J., Choi J., Jeon H.J., Seo M.J., Lee B.Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 suppresses early stage of adipocyte development via activation of C/EBP homologous protein-10 in 3T3-L1 and attenuates fat accumulation in high fat diet-induced obese zebrafish. J Ginseng Res. 2017;41:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aune U.L., Ruiz L., Kajimura S. Isolation and differentiation of stromal vascular cells to beige/brite cells. J Vis Exp. 2013 doi: 10.3791/50191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia R.A., Roemmich J.N., Claycombe K.J. Evaluation of markers of beige adipocytes in white adipose tissue of the mouse. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2016;13:24. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Sanchez N., Moreno-Navarrete J.M., Contreras C., Rial-Pensado E., Ferno J., Nogueiras R., Dieguez C., Fernandez-Real J.M., Lopez M. Thyroid hormones induce browning of white fat. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:351–362. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez-Crespo M., Csikasz R.I., Martinez-Sanchez N., Dieguez C., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., Lopez M. Essential role of UCP1 modulating the central effects of thyroid hormones on energy balance. Mol Metab. 2016;5:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez M., Varela L., Vazquez M.J., Rodriguez-Cuenca S., Gonzalez C.R., Velagapudi V.R., Morgan D.A., Schoenmakers E., Agassandian K., Lage R. Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nat Med. 2010;16:1001–1008. doi: 10.1038/nm.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrovic N., Walden T.B., Shabalina I.G., Timmons J.A., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7153–7164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rong J.X., Qiu Y., Hansen M.K., Zhu L., Zhang V., Xie M., Okamoto Y., Mattie M.D., Higashiyama H., Asano S. Adipose mitochondrial biogenesis is suppressed in db/db and high-fat diet-fed mice and improved by rosiglitazone. Diabetes. 2007;56:1751–1760. doi: 10.2337/db06-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sell H., Berger J.P., Samson P., Castriota G., Lalonde J., Deshaies Y., Richard D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonism increases the capacity for sympathetically mediated thermogenesis in lean and ob/ob mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3925–3934. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortega S.P., Chouchani E.T., Boudina S. Stress turns on the heat: regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and UCP1 by ROS in adipocytes. Adipocyte. 2017;6:56–61. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2016.1273298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calderon-Dominguez M., Mir J.F., Fucho R., Weber M., Serra D., Herrero L. Fatty acid metabolism and the basis of brown adipose tissue function. Adipocyte. 2016;5:98–118. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2015.1122857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hardie D.G., Ross F.A., Hawley S.A. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Habinowski S.A., Witters L.A. The effects of AICAR on adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:852–856. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaidhu M.P., Frontini A., Hung S., Pistor K., Cinti S., Ceddia R.B. Chronic AMP-kinase activation with AICAR reduces adiposity by remodeling adipocyte metabolism and increasing leptin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1702–1711. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M015354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giri S., Rattan R., Haq E., Khan M., Yasmin R., Won J.S., Key L., Singh A.K., Singh I. AICAR inhibits adipocyte differentiation in 3T3L1 and restores metabolic alterations in diet-induced obesity mice model. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2006;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi H.S., Jeon H.J., Lee O.H., Lee B.Y. Dieckol, a major phlorotannin in Ecklonia cava, suppresses lipid accumulation in the adipocytes of high-fat diet-fed zebrafish and mice: inhibition of early adipogenesis via cell-cycle arrest and AMPKalpha activation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59:1458–1471. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson-Fritch L., Burkart A., Bell G., Mendelson K., Leszyk J., Nicoloro S., Czech M., Corvera S. Mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling during adipogenesis and in response to the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1085–1094. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.1085-1094.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gil A., Olza J., Gil-Campos M., Gomez-Llorente C., Aguilera C.M. Is adipose tissue metabolically different at different sites? Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(Suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.604326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu J., Zhang S., Cui L., Wang W., Na H., Zhu X., Li L., Xu G., Yang F., Christian M. Lipid droplet remodeling and interaction with mitochondria in mouse brown adipose tissue during cold treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:918–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim J.H., Yi Y.S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Role of ginsenosides, the main active components of Panax ginseng, in inflammatory responses and diseases. J Ginseng Res. 2017;41:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nedergaard J., Cannon B. UCP1 mRNA does not produce heat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi W.H., Ahn J., Jung C.H., Jang Y.J., Ha T.Y. Beta-lapachone prevents diet-induced obesity by increasing energy expenditure and stimulating the browning of white adipose tissue via downregulation of miR-382 expression. Diabetes. 2016;65:2490–2501. doi: 10.2337/db15-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solmonson A., Mills E.M. Uncoupling proteins and the molecular mechanisms of thyroid thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2016;157:455–462. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wanders R.J., Komen J., Kemp S. Fatty acid omega-oxidation as a rescue pathway for fatty acid oxidation disorders in humans. FEBS J. 2011;278:182–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez-Hurtado E., Lee J., Choi J., Wolfgang M.J. Fatty acid oxidation is required for active and quiescent brown adipose tissue maintenance and thermogenic programing. Mol Metab. 2018;7:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmadian M., Duncan R.E., Jaworski K., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Sul H.S. Triacylglycerol metabolism in adipose tissue. Future Lipidol. 2007;2:229–237. doi: 10.2217/17460875.2.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fransen M., Lismont C., Walton P. The peroxisome-mitochondria connection: how and why? Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18061126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu L., Zhang L., Li B., Jiang H., Duan Y., Xie Z., Shuai L., Li J., Li J. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates energy metabolism through modulating thermogenesis in adipose tissue. Front Physiol. 2018;9:122. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiefer F.W. The significance of beige and brown fat in humans. Endocr Connect. 2017;6:R70–R79. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]