Abstract

Undergraduate medical education traditionally consists of 2 years of lecture-based courses followed by 2 years of clinical clerkships. However, over the past couple decades, undergraduate medical education has been evolving toward non-lecture-based integrated curriculums, requiring a collaborative curriculum. Additionally, e-learning platforms have become efficacious and essential to delivering education asynchronously to students. At Thomas Jefferson University, the Pathology and Obstetrics and Gynecology departments collaborated to create a pilot series of case-based asynchronous interactive modules to teach gynecologic pathology in a clinical context, while interweaving other educational components, such as evidence-based medicine, clinical skills, and basic sciences. The case-based asynchronous interactive modules were given to third-year medical students during their obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Students interpreted histologic and clinical images while being evaluated on clinical management skills, gynecologic diagnoses, general principles of population health and pathology. Sixty-eight students from 3 blocks completed a pre and posttest. All participants showed improvement in interpreting gynecologic pathology in routine clinical scenarios as well as improved case-based decision-making, with an average score increase by 5.7%. Learner feedback was positive, with suggestions to apply this method to other medical specialties, particularly radiology. Asynchronous interactive modules are an efficacious and popular method of pathology education.

Keywords: asynchronous, case-based, interactive, medical, module, pathology, undergraduate

Introduction

Undergraduate medical education (UME) has traditionally followed a specific format in which students receive 2 years of lecture-based medical school courses followed by 2 years of clinical clerkships.1 However, as described by Irby et al, this structure of medical education is “inflexible, overly long, and not learner-centered.”2 Teaching basic sciences as distinct disciplines in a rigid curriculum has promoted an overemphasis on details rather than a conceptual and integrated understanding to medicine and the patient experience.1,3 The Carnegie Foundation issued a report in 2010 that emphasized the need to integrate knowledge in basic, clinical, and social sciences, with clinical experience in the medical education curriculum to adequately represent the integrated nature of physicians’ learning and work.2 Over the past few years, UME has been moving toward integrated curricula that present knowledge in “a contextual manner across traditional disciples, integrating information, improving retention, and facilitating application to clinical practice,” while incorporating interactive teaching methods such as case- and team-based learning.1

At the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University (TJU), an integrated curriculum was introduced in the academic year 2016-2017 (Figure 1). Preclinical time was reduced from 24 months to 21 months, where students are taught the foundations of medicine by organ systems through lecture, team- and case-based learning, while also beginning clinical encounters that are appropriate to their competence level. Students then spend a year doing the core clinical rotations, followed by a yearlong curriculum focused on their chosen residency. Multiple basic sciences, including pathology, are threaded throughout the curriculum. This reform encourages understanding of basic principles in clinical decision-making and allows essential principles in pathology to be delivered to students in a clinical context, thereby maintaining the visibility of pathology in an integrated curriculum.1 In addition to the more scientific aspects of medicine, the integrated curriculum also includes humanities courses as well as scholarly inquiry requirement.

Figure 1.

JeffMD Curriculum Overview at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Copied with permission of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Original figure located at https://www.jefferson.edu/university/jeffmd-curriculum-overview.html).

One of the challenges to teaching pathology in an integrated curriculum is that due to the lack of a “stand-alone” pathology course in combination with decreased preclinical time is that careful decisions must be made as to how and when to best present pathology education, as there is no longer protected time for the pathology curriculum. Although integrated curriculums often intend to revisit basic medical sciences in the clinical context, this may require logistical negotiation, as clinical rotations often involve multiple sites, rotation duties with varying schedules, as well as coordination with multiple rotation directors. It requires the combined efforts of several faculty members, including the course directors, block leaders, program directors, and deans.2 One way to alleviate these logistical issues is through e-learning.

Multiple studies have shown the benefits of e-learning in medical education. Fransen et al4 evaluated the use of an e-learning platform by medical students as a supplement to conventional teaching of dermatology during the clinical clerkship. Their findings showed a significant impact in knowledge gained from the use of the e-learning tool (P < .0000). The benefit of e-learning in teaching complex or conceptually difficult topics to medical students has also been evaluated. Morgulis et al5 evaluated the impact of an e-learning module on leukemia for senior medical students compared to other online resources and also showed a significant difference in mean percentage scores between a study group and control group (study: 80 ± 3; control: 66 ± 3; P < .001).

Other studies have analyzed the benefit of e-learning in teaching topics related to pathology. Ariana et al6 developed an electronic self-directed learning tool that consisted of practical lecture notes on general and systemic pathology topics as well as interactive microscopy slides to teach histopathology to dental students in addition to traditional lectures. Final course assessments compared between the study and control cohorts showed that the study cohort had significantly higher scores (P < .01). Additionally, Riccioni et al7 described the “ICT (Information and Communication Technology) eModules on HistoPathology: a useful online tool for students, researchers and professionals-HIPON” project launched in 2013. The e-learning platform combines virtual slides, educational videos, and interactive images with questions and answers with the aim to convey a professional pathologist experience. At the time, a midterm report of the project evaluated by the Education, Audiovisual, and Culture Executive Agency in Europe was considered favorable.

The use of e-learning in teaching pathophysiology while integrating other preclinical courses has also been studied. Tse and Lo8 integrated pathophysiology and pharmacology in a web-based e-learning course for first-year nursing students. The authors note that knowledge and understanding of pathophysiology and pharmacology are often felt to be limited by nursing students; therefore, an emphasis on improving the application and integration of these subjects in clinical practice is warranted. Through the use of the web-based e-learning course, the students were able to understand the subject content and improve their clinical decision-making skills while having the flexibility and convenience associated with e-learning.

In addition to being efficacious, e-learning has the added benefit of being asynchronous. Asynchronous education is a student-centered modality of teaching that is untethered to time or location.9 This helps alleviate some of the logistical issues presented by teaching a large number of students during a clinical rotation. Asynchronous education is not only preferred by learners but also effective.10 E-learning platforms not only provide content but can also present the content through enhanced tools and multimedia, creating interactive assimilated cases.9

Case-based learning is a particularly efficacious way of presenting pathology knowledge during clinical rotations. As described by Malau-Aduli et al, case-based learning “ensures the consolidation of newly acquired knowledge through its application and discussions.”11 Case- and team-based learning strategies allow students to receive a more advanced application of knowledge rather than through traditional lecture series.12 Several studies have investigated the use of case-based learning in pathology. McBride and Prayson13 used a case-based approach in the development of the microanatomy curriculum at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. This format engaged students through interactive seminars while integrating various learning objectives. Dubey and Dubey14 explored the use of case-based learning in pathology through 4 case scenarios involving the hepatobiliary system that were administered to medical students after didactic lectures. Out of 81 students who participated, 80 (98.77%) communicated that the cases made learning the topic more interesting, and 78 (96.30%) students felt more confident in handling the case situations. Case-based learning also caused highly significant improvement (P < .0001) in higher-level cognition, and 95.06% of students expressed a desire for additional sessions in other topics. These findings emphasize how case-based learning promotes interest and development in critical thinking.

Our study used a case-based asynchronous interactive module (AIM) to teach cervical pathology to third-year medical students on their obstetrics and gynecology rotation. Additional goals for this case-based AIM included interweaving other educational components, such as evidence-based medicine, clinical skills, and basic sciences to exemplify an integrated curriculum within the module, while highlighting principles of pathology and the role of pathologists in clinical medicine.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the TJU Institutional Review Board and it was financed through the institution’s Center for Teaching and Learning. One hundred thirty-nine medical students provided written informed consent prior to participation.

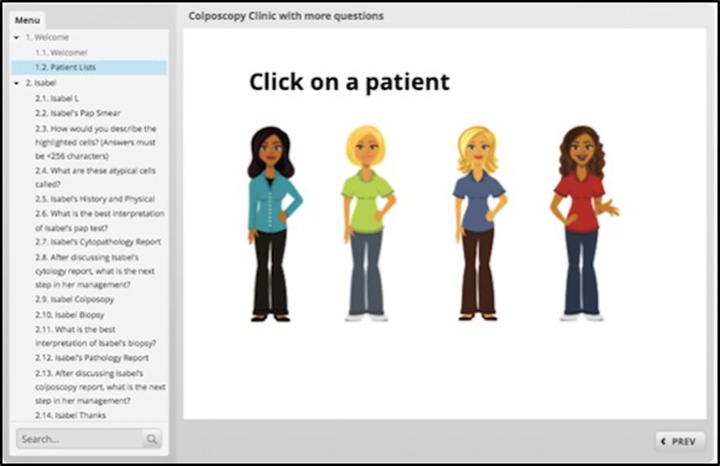

A case-based AIM was collaboratively created by the Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB-GYN) clerkship director (Dr Katherine Lackritz) and the Pathology clerkship director (Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan) using the e-learning software Articulate (New York, New York). The AIM simulated 4 colposcopy clinic patients from their initial Pap smear to their definitive diagnosis. The initial slide of the module depicts the hypothetical patients with a navigation tool (Figure 2). The 4 hypothetical patients included a 21-year-old female with Pap smear findings consistent with reactive cellular changes, a 29-year-old female with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, a 31-year-old female with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, and a 42-year-old female with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix.

Figure 2.

Introductory slide of the AIM with 4 hypothetical patients and a navigation tool on the left-hand side (Copied with permission of Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan. Original figure located at https://360.articulate.com/review/content/08116c73-85a5-4882-b349-f453c7064c4d/review). AIM indicates asynchronous interactive module.

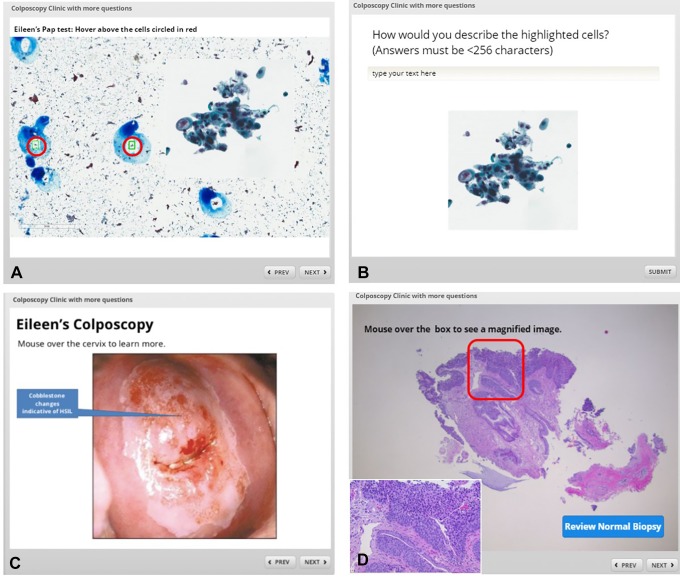

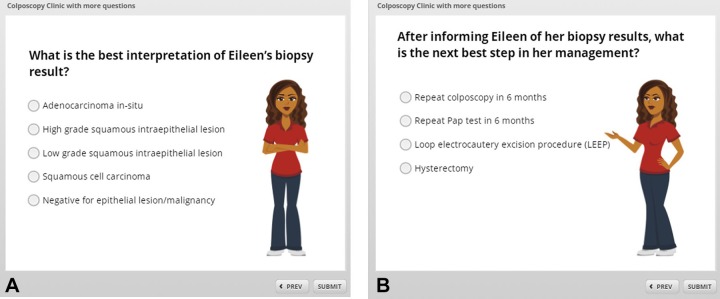

Each case begins with a simulated history and physical that was collaboratively created by the OB-GYN and Pathology clerkship directors. As an example, the case of Eileen, a 31-year-old female who presents for her first OB-GYN check-up in 5 years, is described (Figure 3). As the case progresses, students were given an interactive deidentified Pap smear and were encouraged to use descriptive terminology they learned in the preclinical years (Figure 4A-B). Additional interactive deidentified clinical and histologic images followed, including a colposcopy photograph provided by the OB-GYN clerkship director (Figure 4C-D). Students were evaluated on their interpretation of results and clinical decision-making skills through multiple- choice questions (Figure 5), from which students received active feedback based on their choices. The cases conclude after completing the review of pathology concepts in clinical decision-making.

Figure 3.

Simulated history and physical examination of Eileen, a 31-year-old female (Copied with permission of Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan. Original figure located at https://360.articulate.com/review/content/08116c73-85a5-4882-b349-f453c7064c4d/review).

Figure 4.

Deidentified Pap smear with interactive fields where students can see suspicious groups of cells at higher power (A) and insert descriptive terms (B). Interactive colposcopy with descriptive texts (C) and histologic pictures illustrating pathologic principles (D) were also embedded in the simulated case (Copied with permission of Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan. Original figure located at https://360.articulate.com/review/content/08116c73-85a5-4882-b349-f453c7064c4d/review).

Figure 5.

Multiple choice questions regarding interpretation of results (A) and best step in clinical management (B) (Copied with permission of Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan. Original figure located at https://360.articulate.com/review/content/08116c73-85a5-4882-b349-f453c7064c4d/review).

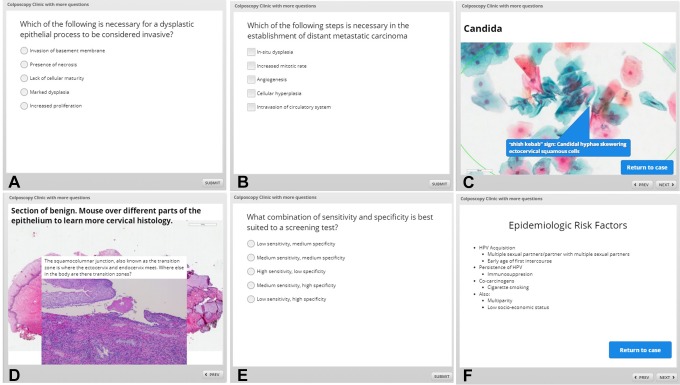

Topics from other relevant threads were presented in the module as well. Concepts in general principles of pathology, nonneoplastic/infectious diseases, normal histology, statistics, and population health (Figure 6A-F) were also reviewed interactively.

Figure 6.

Multiple threads including concepts in general pathology (A-B), cytologic images of common nonneoplastic/infectious diseases (C), an interactive overview in normal histology (D), and statistics/epidemiology (E-F) were incorporated into the module (Copied with permission of Dr Joanna S. Y. Chan. Original figure located at https://360.articulate.com/review/content/08116c73-85a5-4882-b349-f453c7064c4d/review).

The module was given to the third-year medical students midway through their OB-GYN clerkship through the e-learning software Blackboard Learn (Washington, DC). Students were given a reading assignment to complete prior to the module. The students voluntarily completed a 7-question premodule assessment and a postmodule assessment that had no bearing on their course grades. Students’ names were not recorded to maintain anonymity, and students provided an arbitrary 4-digit number on the tests instead. Scores were recorded as a percentage. Of note, there was no designated passing score.

The pre- and post-test scores for each student were compared using a paired t test. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. The Graphpad QuickCalcs software (La Jolla, California) was used to perform the analyses.

Results

Out of 139 students, 68 students in 3 blocks (1, 3, and 4) completed the pre- and posttest. The results are summarized in Table 1. The average score increased by 5.7%, and the range of score increases across the 3 blocks was between 3.86% and 8.16%. Block 4 showed a significant difference between the pretest average score (77.71%) and the posttest average score (85.87%; P value: .0034). Additionally, although blocks 1 and 3 showed an improvement in score between the pretests (90% and 87.57%, respectively) and posttests (95.29% and 91.43%, respectively), the improvement was not statistically significant (P value: .2243 and .06881, respectively). Learner feedback was universally positive, with suggestions to apply this method to other subspecialties, including radiology.

Table 1.

Average Pre and Postassessment Scores.*

| Block | Pretest Average % | Posttest Average % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 95.29 | .2243 |

| 3 | 87.57 | 91.43 | .06881 |

| 4 | 77.71 | 85.87 | .00345 |

*P value < .05 considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Over the past couple decades, UME has increased integration of fundamental medical sciences throughout the curriculum, while incorporating case- and team-based learning methods.1,3,11 An asynchronous education component provided through e-learning offers a flexible method to reinforce pathology education in clinical rotations of an integrated curriculum. E-learning programs have become a well-received adjunct to the medical education curriculum.4

This study demonstrates that integrating pathology into clinical rotations in an integrated curriculum is a popular and efficacious way of reinforcing pathologic concepts in the clinical setting. Students gained pathology knowledge that otherwise would not be presented to them in a clinical setting. Using a case-based format presented pathology concepts in a manner that could be immediately applicable in the clinical setting, therefore highlighting the significance of pathology in patient care.

An added benefit of using a case-based model was the ability to teach the importance of pathologists in health-care decision-making. The cases highlighted the role of pathologists in adding value to the health-care system, exposing students to pathology as a medical profession during a required component of their clinical education.

Although there are several benefits to AIMs, and e-learning in general, certain disadvantages are noted. Traditional classroom lectures have the benefit of regular contact with faculty that can allow students to solve their learning issues and ask questions face-to-face,8 which caters to students who thrive in a classroom setting. One way this may be at least partially alleviated is the use of discussion boards as well as “chat” applications which can allow for virtual “office hours” which create space for individual student attention. Additionally, the development of cases through e-learning can be time-consuming due to the learning curve of using new technologies.9 Teaching resource centers can be an invaluable resource in overcoming the technological challenges of creating an e-learning environment.

There were several limitations to this study. The number of students who participated in the pilot series was small, which may have affected the variability in significance among the groups, and their performance was not compared to a control group (ie, a group of students that were given lecture-based education only on the subject). Additionally, the study design analyzed short-term retention of knowledge as the posttest was completed soon after the module. Future studies could determine whether e-learning methods improve long-term knowledge retention and understanding of gynecologic pathology principles in clinical medicine.

In this study, each block that participated showed an improvement in knowledge gained from using AIMs. However, similar to the aforementioned studies and others, our students enjoyed using the AIMs and suggested that the AIMs be applied to other subspecialties, including radiology.

Conclusions

Case-based AIMs are an efficacious and popular method of teaching pathology. The asynchronous nature of the course can alleviate some logistical issues of teaching pathology in a clinical rotation. Making the modules case-based reinforces pathology principles in a clinical context, highlighting how pathology concepts should influence patient care. In addition, case-based AIMs help integrate multiple disciplines while highlighting the role of pathology in clinical management. Future directions include collaborating with other departments to create modules that help teach and contextualize the role of both pathologists and principles of pathology in clinical management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Julie Phillips from the TJU Center for Teaching and Learning for her help with the Articulate software.

Authors’ Note: This study was previously introduced in an abstract published at the Association of Pathology Chairs 2018 Annual Meeting in San Diego, California (original abstract located at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289518788096#_i123).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The use of Articulate was financed through the TJU Center for Teaching and Learning.

References

- 1. Sadofsky M, Knollmann-Ritschel B, Conran RM, Prystowsky MB. National standards in pathology education: developing competencies for integrated medical school curricula. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:328–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2013-0404-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Irby DM, Cooke M, O’Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85:220–227. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vidic B, Weitlauf HM. Horizontal and vertical integration of academic disciplines in the medical school curriculum. Clin Anat. 2002;15:233–235. doi:10.1002/ca.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fransen F, Martens H, Nagtzaam I, Heeneman S. Use of e-learning in clinical clerkships: effects on acquisition of dermatological knowledge and learning processes. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgulis Y, Kumar RK, Lindeman R, Velan GM. Impact on learning of an e-learning module on leukaemia: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:36 doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ariana A, Amin M, Pakneshan S, Dolan-Evans E, Lam AK. Integration of traditional and E-learning methods to improve learning outcomes for dental students in histopathology. J Dent Educ. 2016;80:1140–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riccioni O, Vrasidas C, Brcic L, et al. Acquiring experience in pathology predominantly from what you see, not from what you read: The HIPON e-learning platform. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:439–445. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S79182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tse MM, Lo LW. A web-based e-learning course: integration of pathophysiology into pharmacology. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:919–924. doi:10.1089/tmj.2008.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choules AP. The use of elearning in medical education: a review of the current situation. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:212–216. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.054189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, Stroud S, Dawson M, Fix M. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med. 2014;89:598–601. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malau-Aduli BS, Lee AY, Cooling N, Catchpole M, Jose M, Turner R. Retention of knowledge and perceived relevance of basic sciences in an integrated case-based learning (CBL) curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:139 doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, Stoller JK. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88:1418–1423. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McBride JM, Prayson RA. Development of a synergistic case-based microanatomy curriculum. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1:102–105. doi:10.1002/ase.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dubey S, Dubey AK. Promotion of higher order of cognition in undergraduate medical students using case-based approach. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:75 doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_39_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]