Abstract

As the opioid crisis continues to have devastating consequences for our communities, families, and patients, innovative approaches are necessary to augment clinical care and the management of patients with opioid use disorders. As stewards of health analytic data, laboratories are uniquely poised to approach the opioid crisis differently. With this pilot study, we aimed to bridge laboratory data with social determinants of health data, which are known to influence morbidity and mortality of patients with substance use disorders. For the purpose of this pilot study, we focused on the co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines, which can lead to an increased risk of fatal opioid-related overdoses and increased utilization of acute care. Using the laboratory finding of the copresence of benzodiazepines and opioids as the primary outcome measure, we examined social determinants of health attributes that predict co-use. We found that the provider practice that ordered the laboratory result is the primary predictor of co-use. Increasing age was also predictive of co-use. Further, co-use is highly prevalent in specific geographic areas or “hotspots.” The prominent geographic distribution of co-use suggests that targeted educational initiatives may benefit the communities in which co-use is prevalent. This study exemplifies the Clinical Lab 2.0 approach by leveraging laboratory data to gain insights into the overall health of the patient.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, opioids, social determinants of health, substance use disorder, Clinical Lab 2.0

Introduction

The prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in the United States represents a public health crisis of astounding proportions. As early as 2002, substance use emerged as the single, most prominent factor in preventable illness, associated health-care costs, and related social challenges.1 The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) alone is astronomically high, with over 2.5 million Americans over 12 years of age exhibiting this disease.2 At a time when the overall cause of death from opioids exceeds that of motor vehicle crashes,3 collaborative and innovative strategies are essential.

One significant contributor to fatal opioid-related overdoses is the co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines, accounting for approximately 30% of fatal opioid-related overdoses.4 In various issued statements and labeling requirements, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has urged significant caution in the co-use of these drugs.5 The co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines is a significant public health risk through the increased risk of respiratory depression in patients with OUD.4

In the SUD population, broadly, and in OUD, in particular, the interplay of medical and social support is paramount to successful patient management. Individuals with SUD have both significant physical and behavioral health requirements that drive high health-care utilization and cost.6 The role of social determinants of health (SDH) in impacting patients with SUD and the accompanying comorbid conditions has been long-recognized.7 For example, socioeconomic status is inversely correlated with increased drug-related morbidity and mortality; it also shapes access to care, quality of care, and prevention efforts in individuals who use drugs.8 Homelessness and incarceration have also been linked to poorer health outcomes in this population, shifting access to medical insurance, access to care, and increasing the risk of blood-borne infectious disease.9 Further, the risk of mortality from overdose is significantly higher in the 2 weeks following incarceration.10

Screening for key SDH predictors during the patient visit has been championed as critical step to supporting the holistic management of SUD patients .11 Universal screening for SDH attributes is a foundational element for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services $157 million program, called the Accountable Health Communities.11 However, even with extensive effort, the implementation of this screening can be arduous and variably applied.11 Further, patient interview may not identify predictors that, while impactful, are not known or considered by the patient such as geographic region, driving distance to healthy food options, or relative levels of access to transportation. Given the importance of value-based delivery of health-care services and efficient use of physician time,12,13 increased reliance on predetermined digital data can be used to expedite patient–provider information gathering and bolster conversations that impact SDH in conjunction with the delivery of care and improving outcomes.

In a predictive modeling paradigm, we paired a previously determined database of SDH predictors with the precision of laboratory data in our SUD population to identify what critical social determinants would predict the high-risk behavior of concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines, a readily identified laboratory finding.

Methods

This pilot project integrated SDH, available through Staple Health (a data science organization focused on using SDH to predict patient risk and identify optimal interventions) with laboratory data from Aspenti Health (a laboratory focused on population health in SUD).

The laboratory data included urine drug testing results for 37 797 unique urine samples collected from October 22, 2018, to March 5, 2019. Laboratory data included patient samples from practices within Vermont, New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Maine, and Iowa with >90% derived from 2 states: Vermont and Massachusetts. This likely represents approximately a third of SUD testing in the state of Vermont and only a small fraction of testing in Massachusetts. The data set used for this study is predominantly composed of urine drug testing data from patients in treatment for SUD. Urine drug testing in this setting is used to monitor treatment adherence, recognize relapse, or identify unexpected drug use.

The laboratory results introduced into the model were generated at a centralized testing laboratory (Aspenti Health) and pulled from the laboratory’s information system (LIS). A subset of this data identifying the copresence of opioids and benzodiazepines was introduced into the model. The presence of opioid-related compounds was defined as the presence of any of the following compounds: oxycodone, morphine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, fentanyl, heroin metabolite (6-acetylmorphine), buprenorphine, and methadone or related classes, by either screening or confirmation methodology. The presence of benzodiazepine compounds was defined as the presence of any of the following compounds: 7-aminoclonazepam, α-hydroxy-alprazolam, lorazepam, midazolam, nordiazepam, temazepam, oxazepam, or related classes by either screening or confirmation testing. The window of detection in urine varies based on the compound and the individual’s pharmacokinetic profile but ranges between 1 and 7 days.14 Since urine drug testing verifies drug consumption, it is an effective measure of co-use. Samples in the data set were flagged as either positive or negative for co-use of opioids or benzodiazepines.

A subset of 21 unique SDH predictive features were selected for inclusion in this model (see Table 1) from more than 250 SDH attributes available through Staple Health. The first variable listed in Table 1 is the practice. The practice represents the organization that a patient attends for SUD treatment. This may be an individual provider or a group of providers. These SDH attributes were combined with an additional 8 attributes associated with the sample (sample characteristics) available through Aspenti Health’s laboratory LIS. These features were selected for inclusion based on known correlates with SUD as well as the availability of data in this population. Features include patient-level factors as well as social and geographic factors ranging from indicators of food access, housing, employment, and crime statistics.

Table 1.

The 29 SDH and Sample Characteristics Used in the Model.*

| Feature | Unit of Measure | Relative Model Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Practice | Patient | 0.398 |

| Patient age | Patient | 0.150 |

| Percent on public assistance | Census block group | 0.047 |

| Patient sex | Patient | 0.044 |

| Distance from address to supermarket, km | Patient | 0.041 |

| Block group | Census block group | 0.036 |

| Collection time: minute | Patient | 0.022 |

| Collection day of the month | Patient | 0.022 |

| Percent unemployed | Census block group | 0.019 |

| Staple economic stress index (SESI) | Census block group | 0.018 |

| Average commute time | Census block group | 0.017 |

| Collection time: hour | Patient | 0.017 |

| House value index | Patient | 0.017 |

| Percent single parent | Census block group | 0.014 |

| Distance from address to grocery store, km | Patient | 0.014 |

| Distance from address to convenience store, km | Patient | 0.013 |

| Percent households with more than 1 person living per room | Census block group | 0.013 |

| Collection time: day of week | Patient | 0.013 |

| Percent of households below 200% FPL | Census block group | 0.013 |

| Percent of households below 100% FPL | Census block group | 0.012 |

| Percent of individuals over 25 with no high school degree | Census block group | 0.011 |

| Predicted income | Patient | 0.011 |

| Percent of households with no car | Census block group | 0.010 |

| Collection time: second | Patient | 0.009 |

| Collection time: month | Patient | 0.008 |

| Household size, sqft | Patient | 0.007 |

| Household income bracket | Patient | 0.001 |

| Number of generations living in household | Patient | 0.001 |

| Collection time: year | Patient | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; SDH, social determinants of health.

*Census block group: Smallest unit of measure published by the US census, containing between 600 and 3 000 people. Staple economic stress index (SESI) is calculated by block group based on factors related to economic stress including the percent of households below the federal poverty limit, single parent families, access to transportation, levels of education, and crowded living situations. Supermarket, grocery store, and convenience store: 3 levels of granularity are provided for distance to food sources including supermarket, grocery store, and convenience store. All 3 variables have been included due to differences in relative influence in the model.

The selected SDH attributes were paired with urine drug testing data to support the management of SUD patients. Predictive models were trained on the provided historical laboratory data sets described above to determine which SDH is most predictive of co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines. This merged data set was deidentified for analysis. Authors were blinded to individual identifiers for this study and the study has been deemed not human subject research and is exempted from full institutional review board review by the University of Vermont Health Network institutional process.

Throughout the analysis process, 128 unique models were built and evaluated. These included logistic regressions, decision trees, random decision forests, and deep-learning models. Models were compared based on area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC), an objective measure commonly used to compare and evaluate binary classification models for overall performance of the model, taking into account both sensitivity and specificity. The π coefficient (also known as the Matthews correlation coefficient), a second measure of the quality of a binary classifier, was also used given this measure works particularly well in imbalanced data sets where there are relatively few positive outcomes, as can occur in clinical data.

As a critical value of this type of modeling is to identify a specific patient’s risk, the ability to interpret the modeling process and explain each prediction were prioritized. The initial extract of patient test data from the Aspenti LIS was cleaned of duplicates and redundant data and patients without an address or date of birth were removed.

Results

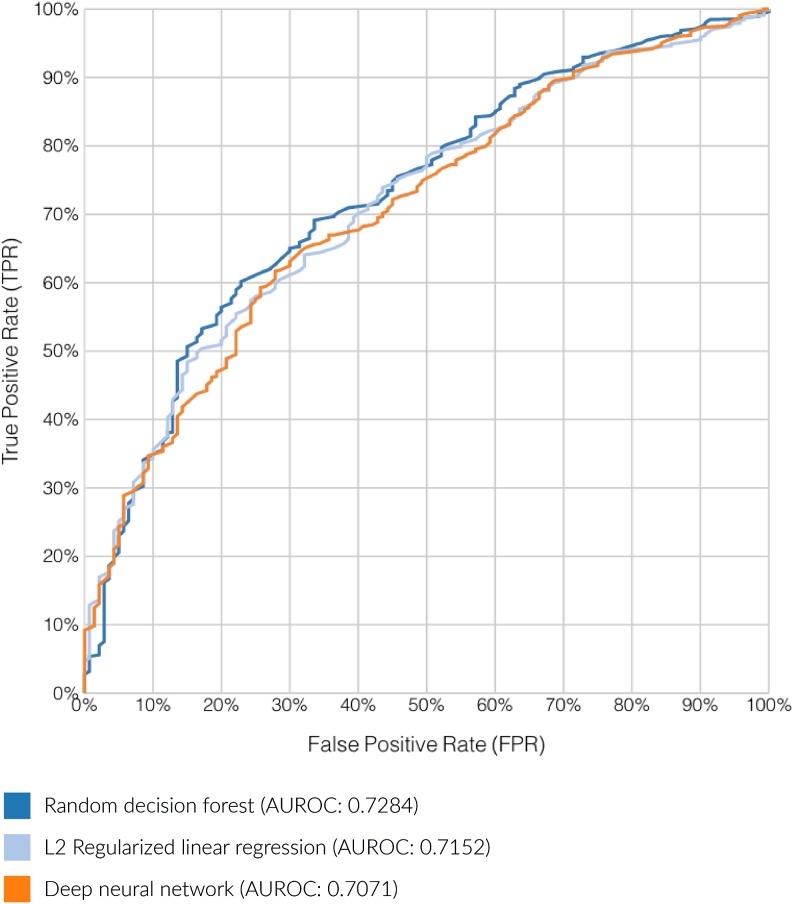

A subset of 6950 unique patients found to have the requisite information for SDH matching and analysis, with a total of 750 (10.8%) flagged for co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines. After initial model building and evaluation, 3 top performing candidates warranted further investigation: An L2 regularized logistic regression (AUROC 0.7152), a deep neural network (AUROC 0.7070), and a bagged (bootstrap aggregated) random decision forest (AUROC 0.7284). The relative performance of these 3 models is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) demonstrating the relationship between true positive rate (sensitivity) and false positive rate for the top 3 performance models.

The random decision forest was selected based on overall model performance (largest AUROC score), as well as the ability of pruned random forests to manage issues of overfitting. This “forest” was built through an ensemble of 46 unique random decision trees. A benefit of this model is the ability to extract detailed explanations of individual prediction results from this type of model, an important feature in a clinical setting. The relative global influence of SDH predictors within the model was defined as a normalized measure of error reduction that each variable imparts on the final model. As mentioned earlier, this model achieved an AUROC score of 0.7284 and a maximum π coefficient of 0.2275. These results indicate a moderately strong predictive model for this initial proof of concept work.

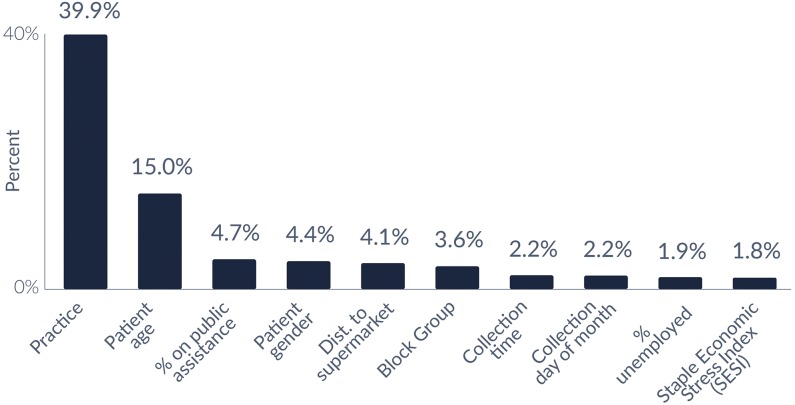

Specific SDH variables were reviewed to assess their relative influence in the selected model predicting co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines. The 10 most influential factors for the selected model are presented in Figure 2, which accounted for 79.8% of the overall influencers in this model. The 2 most influential global predictors of co-use were the practice from which the laboratory test was ordered and the age of the patient.

Figure 2.

The 10 most common SDH and sample characteristics for co-use of opioid and benzodiazepines. Note: Neighborhood is defined as the census block group in which a patient’s address is located; SESI is calculated by block group based on factors related to economic stress including the percentage of households below the federal poverty limit, single parent families, access to transportation, levels of education, and crowded living situations. The top 10 most common attributes account for 79.8% of the total prediction of the model. SDH indicates social determinants of health; SESI, staple economic stress index.

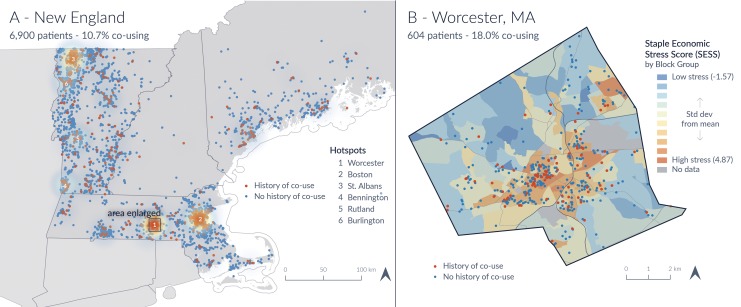

Additionally, by using address latitude/longitude points, a geospatial analysis was completed to further characterize the geographic distribution of patients found to co-use. Overall clustering of co-use in Northern New England can be seen in Figure 3A, whereas the percentage of co-use presented for the 20 towns with the most co-use can be seen in Table 2. Co-use percentages ranged from 0% to 33.33% for towns across the analysis region. Figure 3B displays a more detailed view of Worcester, Massachusetts, the region with the highest density of co-use. This map presents a graphical overlay of co-use with an economic stress index, which was not demonstrated to be a top global predictor (1.8% overall influence, see Figure 2), and demonstrated no obvious pattern or distribution.

Figure 3.

A, Geographic hotspots of co-use throughout Northern New England region. Numerically labeled geographic locations correspond to the locations of higher co-use (in ranked order). B, An example of 1 geographic hotspot of Worchester, Massachusetts, with SDH overlay of an economic stress score by local region. This corresponds to geographic “hot spot” #1 in A. Orange circles reflect co-use. Blue circle denotes no co-use. Note: Individual points on this map have been given a small amount of random latitude–longitude shift to preserve confidentiality. SDH indicates social determinants of health.

Table 2.

The Top 20 Towns Ordered by Percentage of Co-Use Among the Study Population.*

| Percent of Patients Found to Co-use | Town | State | Population (Last Available Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 33.3 | Montpelier | Vermont | 7484 (2017) |

| 32.1 | Wilmington | Vermont | 1876 (2010) |

| 28.6 | Portland | Maine | 66 822 (2017) |

| 28.6 | Webster | Massachusetts | 17 020 (2017) |

| 20.5 | St Albans Town | Vermont | 6971 (2011) |

| 19.2 | Johnson | Vermont | 3614 (2017) |

| 18.5 | Highgate | Vermont | 3654 (2017) |

| 18.3 | Swanton | Vermont | 6427 (2010) |

| 18.1 | Worcester | Massachusetts | 185 677 (2017) |

| 17.3 | St Albans City | Vermont | 6918 (2010) |

| 15.6 | Barre Town | Vermont | 9066 (2011) |

| 15.4 | West Rutland | Vermont | 2181 (2017) |

| 14.3 | Fairfax | Vermont | 4669 (2017) |

| 13.6 | Cambridge | Massachusetts | 113 630 (2017) |

| 13.0 | Somerville | Massachusetts | 81 360 (2017) |

| 13.0 | Bennington | Vermont | 15 764 (2010) |

| 12.8 | Hartford | Vermont | 9952 (2010) |

| 12.5 | Sheldon | Vermont | 2190 (2010) |

| 12.5 | South Burlington | Vermont | 19 141 (2017) |

| 11.8 | Shaftsbury | Vermont | 3443 (2017) |

* The lower limit cutoff was set to towns that had at least 20 unique patients in the study population to protect patient confidentiality. Sources: US Census Bureau.

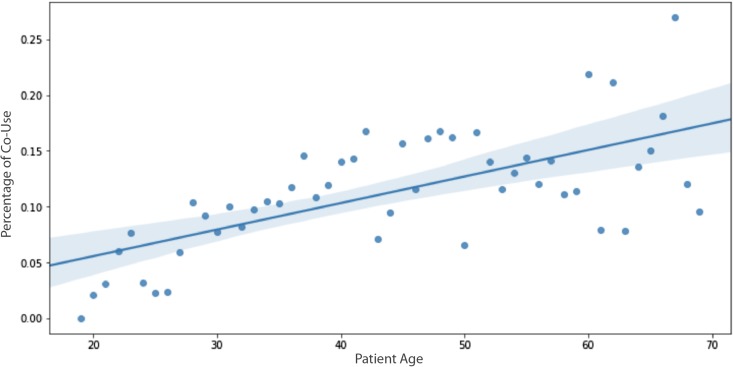

The second most influential SDH predictor for co-use was identified as increasing age. Figure 4 demonstrates the relationship between ages by percentage of co-use. A simple ordinary least squares regression showed a statistically significant relationship between age and co-use (P value <.001, r2 = 0.899).

Figure 4.

Comparison of age by percentage of co-use: correlation of increasing age and co-use. Given the limited sample size, individuals greater than 70 years were excluded from the analysis. The dark blue line represents the linear regression model fit with light blue shading indicating 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This pilot study examined what SDH attributes would predict co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines, as defined by the copresence of opioids and benzodiazepines by urine drug testing, in patients being treated for SUDs.

Although studies have varied widely on the prevalence of co-use in the population with SUD, several studies have identified co-use as high as 50% to 70% of cases.15 Surprisingly, in our analysis, 10.8% of cases were identified as having co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Given we used the broadest possible definition of opioids and benzodiazepines to include treatment with buprenorphine and methadone as opioids, this was unexpected. It is possible that with recent successes of Vermont’s Hub and Spoke Model16 and the high representation of Vermont in this data set that this model may include a more stable treatment population.

Nevertheless, the co-use of these 2 drug classes poses a significant public health risk and has led the US FDA to release its highest warning label for co-use in September 2017.17 Most notably, risks of respiratory depression, overdose, and overdose death are increased in this population with 30% of fatal opioid-related overdoses involving a concurrent benzodiazepine.4 With approximately 50 000 opioid-related overdose deaths per year,18 this amounts to roughly 15 000 preventable deaths attributable to co-use annually. Co-use also results in an increased utilization of acute, episodic care by doubling the rate of emergency room visits and inpatient services.4 A recent analysis suggested that the overall population risk for this type of acute, episodic care would be reduced by 15% if co-use was eliminated.4 With nearly $2 billion dollars in annual hospital costs attributable to patients involved in opioid-related overdoses,19 any risk reduction is economically impactful in this population.

Despite broad awareness of the risk of respiratory depression and the associated risk of overdose in this population, the prevalence of co-use has more than doubled in the past decade.4,17,20 Given the significant adverse outcomes, a deeper characterization of the population that co-uses benzodiazepines and opioids is needed.15 Further, an understanding of attributes that may predict co-use could assist providers in assessing risk in their patients. In this pilot study reviewing 29 SDH and patient attributes, 2 predictors alone accounted for 54.9% of the overall global prediction of our model: the patient age and the practice from which the test was ordered.

The observation that patient age is a predictor of co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines is aligned with extensive literature demonstrating increased use of benzodiazepines with advancing age.21 In a comprehensive study examining approximately 60% of retail pharmacies in the United States, 8.7% of older patients (65-80 years) were prescribed benzodiazepines in contrast to 2.6% of younger individuals (18-35 years). Further, some studies have demonstrated that co-use is more likely in older population.4 Although patient age cannot be changed, the risks associated with age and co-use may inform conversations between provider and patient and help identify a potentially higher risk population.

The second most common predictor of co-use was the practice from which the urine drug test was ordered. Although this second finding does not represent a traditional, patient-specific social determinant of health, it is an interesting factor that increases the likelihood of co-use in our model. Although we observed significant geographic variability with distinct geographic “hot spots” of co-use, this was not predicted by other geographic factors such as census block group or distance to food sources. Rather, the predictor was the practice from which the urine drug test was ordered, suggesting that this relates instead to the given practice or individual provider’s prescribing practices or policies or thus far unassessed unique determinants within individual practice populations. Repeated studies have cited differences in regional and county benzodiazepine and opioid prescribing practices with approximately 6-fold variation in each.22,23 This study suggests that these differences may be identifiable on a practice level and targeted educational interventions may be of utility.

Interestingly, some attributes were not as influential in the current model at predicting co-use. Several geographically determined attributes such as indices related to the economic stressors of a region, percent in a region unemployed and on public assistance, percentage of individuals below the federal poverty line, and census block group were not as predictive in this model. This is in contrast to prior studies which have shown associations between geographic factors such as poverty, unemployment, and zip codes and overdose rates.24 There are a few possibilities that may account for this divergence from previous studies. First, our model differs from several studies that rely upon traditional regression-based approaches to identify patient risk factors in that other models have excluded geospatial labels such as zip code or block group.25,26 This exclusion is often performed to combat issues of multicollinearity. We elected to include the block group label as an input to the model because random decision forests are relatively robust to multicollinearity and the feature had predictive value. Second, this may be due to the high prevalence of rural representation in our data set, which have been shown to have differences in what geographic factors influence overdose.27 It is possible that it may reflect a difference in the outcome measure of co-use rather than overdose, which has been the primary outcome measure in many studies.4,20,27 Finally, it may be that the 2 attributes of age and the practice from which the test was ordered were far more predictive of co-use in this model that they overwhelmed the more traditional findings. Given the small sampling and the fact that this remains a pilot study, future studies will be essential to clarify this.

There remain some limitations to this study. First, as with any work focused on SDH,28 a key limitation is that patients in this population may have instability in many SDH such as gain and loss of insurance or lack of a home address. These factors can challenge algorithmic efforts to appropriately identify all individual patients and limit the use of SDH in specific settings. This can be further exacerbated by transitions into and out of this community. To mitigate this, we employed strategies to limit the impact of these gaps, such as frequently updating data sets, and employing statistics to demonstrate where variability is higher. Second, given the study design, we have little specific information at the practice level including the number and training of providers in the practice. Additional work would be required to understand what provider characteristics are influencing the model. Finally, we recognize that the most significant impact of this work that remains will be in the ability to provide patient-level risk reporting. Identifying risk on a patient level can empower providers and patients to identify SDH factors that can be modified and supported. The overall effectiveness of this reporting strategy will be dependent upon provider adoption and utilization.

This study reflects an initial proof of concept relating a preexisting database of available SDH predictors with laboratory data. This work demonstrates a unique way to marry laboratory data with SDH information. The relative precision of the outcome measure—the co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines through their copresence on a laboratory report—has allowed for exploration of attributes that could predict the prevalence of co-use. Although the patient safety risks of co-use of opioids and benzodiazepines are well-appreciated, the factors that lead to co-use are relatively understudied.15 Further, by using the laboratory finding of co-use, it allows for an expanded discourse on outcome measures beyond the common metrics of overdose, overdose death, emergency department visits, and inpatient stays.19,24,29 Additionally, the goal of this pilot was not only to generate an accurate model but also one that supports its use as a screening strategy for future clinical integration. Using this predictive model and associated infrastructure, care teams will be able to predict a patient’s risk of co-use and understand the key factors driving that risk.

There has been increasing awareness of the importance of SDH in overall wellness and health.30 The increasing emphasis on SDH is likely to improve adoption of this strategy. Many granting agencies and organizations have emphasized the importance of incorporation of SDH into clinical work.31 To our knowledge, this represents the first peer-reviewed publication demonstrating the integration of laboratory data with SDH. This pilot project exemplifies the utility of laboratory data in driving a more holistic approach to substance use management, as championed by the Clinical Lab 2.0 movement.32

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Fung from the University of Vermont Health Network in providing editorial support and mentorship. Further, the authors want to thank the leadership of the Clinical Lab 2.0 movement for inspiring this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This initiative is a cross-institutional effort among 2 companies and 1 nonprofit organization. All authors affiliated with Aspenti Health are employees of Aspenti with the exception of the first author who is employed by the University of Vermont and has no financial interest in Aspenti Health. The single author listed in affiliation with Staple Health has both employment and ownership interest in that organization.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78–93. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sofuoglu M, DeVito EE, Carroll KM. Pharmacological and behavioral treatment of opioid use disorder. Psych Res Clin Pract. 2018;1:4–15. doi:10.1176/appi.prep.20180006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Safety Council, Injury Facts. Odd of Dying. https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/all-injuries/preventable-death-overview/odds-of-dying. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- 4. Sun EC, Darnell BD. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760 doi:10.1136/bmj.j760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA urges caution about withholding opioid addiction medications from patients taking benzodiazepines or CNS depressants: careful medication management can reduce risks. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-urges-caution-about-withholding-opioid-addiction-medications. Accessed June 14, 2019.

- 6. Matthew DB. Un-burying the Lead: Public health tools are the key to beating the opioid epidemic, Brookings Institute. January 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/es_20180123_un-burying-the-lead-final.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2019.

- 7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019. [PubMed]

- 8. Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:S135–S145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dolan K, Moazenb B, Noorib A, Rahimzadeh S, Farzadfarb F, Harigac F. People who inject drugs in prison: HIV prevalence, transmission and prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:S12–S15. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Byrne A, Dolan K. Methadone treatment is widely accepted in prisons in New South Wales. BMJ. 1998;316:1744–1745. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7146.1744a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alley DE, Chisara N, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:8–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1512532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med. 2017;11:3–9. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:S34–S40. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Consensus Statement. Appropriate Use of Drug Testing in Clinical Addiction Medicine. April 5, 2017 www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/appropriate_use_of_drug_testing_in_clinical-1-(7).pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed October 18, 2019.

- 15. Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:8–18. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brooklyn JR, Sigmon SC. Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: development, implementation, and impact. J Addict Med. 2017;11:286–292. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vozoris NT. Benzodiazepine and opioid co-usage in the US population, 1999-2014: an exploratory analysis. Sleep. 2019;42 pii: zsy264. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Understanding the Epidemic. Updated December 19, 2018 www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed August 7, 2019.

- 19. Premier Incorporated, Opioid Overdoses Costing U.S. Hospitals an Estimated $11 Billion Annually. 2019. https://www.premierinc.com/newsroom/press-releases/opioid-overdoses-costing-u-s-hospitals-an-estimated-11-billion-annually Accessed August 7, 2019.

- 20. Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, Ribisl KM, Marshall S. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):85–98. doi:10.1111/pme.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psych. 2015;72:136–42. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maust DT, Lin LA, Blow FC, Marcus SC. County and physician variation in benzodiazepine prescribing to Medicare beneficiaries by primary care physicians in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2180–2188. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4670-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: change in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697–704. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Visconti AJ, Santos GM, Lemos NP, Lemos NP, Burke C, Coffin PO. Opioid overdose deaths in the city and county of San Francisco: prevalence, distribution, and disparities. J Urban Health. 2015;92:758–772. doi:10.1007/s11524-015-9967y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Song R, Hall HI, Harrison KM, Sharpe TT, Lin LS, Dean HD. Identifying the impact of social determinants of health on disease rates using correlation analysis of area-based summary information. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:70–80. doi:10.1177/00333549111260S312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Samuelson MB, Chandra RK, Turner JH, Russell PT, Francis DO. The relationship between social determinants of health and utilization of tertiary rhinology care. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2017;31:376–381. doi:10.2500/ajra.2017.31.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pear VA, Ponicki WR, Gaidus A, et al. Urban-rural variation in the socioeconomic determinants of opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:66–73. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the US. J Pain. 2012;13:988–996. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paulozzi LJ, Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:997–1005. doi:10.1002/pds.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feske ML, Teeter LD, Musser JM, Graviss EA. Counting the homeless: a previously incalculable tuberculosis risk and its social determinants. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:839–848. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Change Health Care. The Eighth Annual Industry Pulse Report. https://www.changehealthcare.com/blog/wpcontent/uploads/change_healthcare_industry_pulse_report_2018.pdf. 2018. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- 32. Crawford JM, Shotorbani K, Sharma G, et al. Improving American healthcare through “Clinical Lab 2.0”: a project Santa Fe report. Acad Pathol. 2017;4 doi:10.1177/2374289517701067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]