Abstract

Background:

Knee pain is common during adolescence, with Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD) being the most frequent condition. Despite this, research regarding the long-term prognosis of OSD is limited.

Purpose:

To evaluate the prognosis 2 to 6 years after the diagnosis of OSD.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study included patients diagnosed with OSD at a single orthopaedic department between 2010 and 2016. Patients were contacted in 2018 and asked to complete a self-reported questionnaire regarding knee pain, knee function (Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS] Sports/Recreation subscale), Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (youth version of EuroQol 5 dimensions 3 levels [EQ-5D-3L-Y]), and physical activity.

Results:

Out of 84 patients, 43 responded. Of these, 60.5% (n = 26) reported OSD-related knee pain at follow-up (median follow-up, 3.75 years). The median symptom duration was 90 months (interquartile range, 24-150 months) for those still experiencing knee pain, and 42.9% of these reported daily knee pain. Fifty-four percent with knee pain had reduced their sports participation compared with 35.3% of those without knee pain. KOOS Sports/Recreation subscale scores were significantly lower in those with knee pain compared with those without knee pain (53 [95% CI, 42-63] vs 85 [95% CI, 76-94], respectively). Participants with knee pain reported lower HRQoL (0.71 [95% CI, 0.57-0.84]) compared with those without knee pain (0.99 [95% CI, 0.97-1.00]).

Conclusion:

This study indicates that OSD may not always be self-limiting. The lower self-reported function and HRQoL in those with continued pain may be a consequence of impaired physical activity due to knee pain.

Keywords: adolescents, apophysitis, overuse injury, KOOS, quality of life

Knee pain is a common complaint in adolescents.16 It accounts for 104 of every 10,000 consultations in general practice every year,20 and one of the most common causes in adolescents is Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD).6 Approximately 10% of adolescents are affected by OSD, with a higher prevalence among those who are very active.6

OSD is thought to be growth related, occurring most commonly in boys between the ages of 12 and 15 years and in girls between the ages of 8 and 12 years.7 OSD is considered a traction apophysitis of the tibial tubercle, caused by high forces from the patellar tendon acting on its attachment during maturation where the growth plate is not yet closed.8 The result is pain, swelling, and enlargement of the tibial tubercle. In some cases, this is also associated with increased thickness of the distal patellar tendon.22 Pain is aggravated by activities that load the quadriceps muscle, for example, jumping, landing, and running.12

OSD is described as a growth-related condition that lasts between 12 and 24 months, with a resolution of symptoms in more than 90% of patients.23 Despite this, almost 8 years after the initial diagnosis of OSD, young adults with a history of OSD have more problems with activities of daily living and sports activity19 compared with those without a history of OSD. Furthermore, research indicates that 50% of athletes still have tenderness in the region of the tubercle after complete ossification of the tibial tubercle, and many continue to have pain in the region of the patellar tendon.13 Çakmak et al3 also reported on the potential for OSD to result in symptoms persisting into adulthood, which contradicts to common assumptions and indicates that OSD may not be as innocuous as previously assumed. Treatment studies are lacking,2 but case reports show that rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice packs are different treatment options.22 As previous studies have been hampered by the lack of patient-reported outcomes as well as small numbers, this presents a barrier to providing evidence-based information to patients about the long-term prognosis and impact of OSD. The aim of this study was to evaluate pain, knee function, physical activity, and quality of life in the short to medium term (2-6 years) after the initial diagnosis of OSD.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a single orthopaedic department between July and August 2018. Ethics approval was waived because of the study’s noninterventional nature. This study is reported following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting cohort studies.21

Population and Recruitment

All patients diagnosed with OSD at a university hospital between 2010 and 2016 were eligible to participate. At the orthopaedic department, patients are diagnosed by an orthopaedic surgeon on the basis of a clinical examination, confirmed by radiography. Patients were identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code for OSD (DM925), supplemented by a free-text search of the notes for words related to OSD (eg, “Osgood,” “Schlatter,” “Morbus Schlatter”). The criterion to include participants was a diagnosis of OSD, by a diagnosis code or listed in the notes, both of which were confirmed by descriptions in the notes. We did not restrict participation to a specific upper age limit, as it is commonly documented in the literature that there can be residual symptoms from “unresolved” OSD in adults, as indicated by persistent swelling and bony changes at the tibial tuberosity.15,24

All eligible participants were invited to answer an online questionnaire (detailed below) via REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Aalborg University.9 Initial contact was made with an SMS directly to each patient with a request to participate in the study and a link to the questionnaire. Participants with no contact details were sent a private message through Facebook by a member of the research team. If participants did not answer within 3 days, they were sent a reminder and again after a week if no response was received. An additional attempt to contact was made via an email sent to personal E-boks with E-boks text message reminders after 3 days and again after a week.

Composition of Questionnaire

Demographics and Characteristics

First, participants were requested to include their full name, sex, age at diagnosis, and years to follow-up in 2018.

Knee Pain

Participants were asked at what age they first received their diagnosis of OSD at the orthopaedic department, in which knee they had pain when they were seen at the orthopaedic department (right, left, or both), and for how many months their knee pain lasted. All participants were also asked if they had received a knee-related diagnosis other than OSD. Next, participants were asked if they still experienced knee pain, which knee they experienced it in currently, and if they had experienced knee pain in the previous week. Participants who still experienced pain or reported pain in the previous week were asked to report pain intensity measured on a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS), pain frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, or rarely), and where they felt the pain (behind my kneecap, around my kneecap, above my kneecap, below my kneecap, inside my knee, the medial side of my knee, the lateral side of my knee, or at the tibia just below my knee). Finally, participants were asked if they experienced pain that influenced daily activities in sites not related to their knees (and if yes, where).

Function, Sport, and Activity

The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) Sports/Recreation subscale was used.19 The KOOS questionnaire has previously been used in similar populations with overuse-related knee pain.14

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

The youth version of the EuroQol 5 dimensions 3 levels (EQ-5D-3L-Y) was used to evaluate HRQol; it is a validated questionnaire used to assess HRQoL in adolescents.1

Sports Participation

Participants were asked about current and prior sports participation. They were also asked if they changed sports because of the onset of knee pain (and if so, provide details).

Treatment

Participants were asked if they had received treatment other than from the university hospital, and if so the type of health care practitioner (ie, general practitioner, physical therapist, chiropractor, orthopaedic surgeon, rheumatologist, or other) and type of treatment (strength exercises, RICE [rest, ice, compression, elevation], painkillers, surgery, advice about sports participation, stretching, knee sleeves, or other). Participants indicated if they used painkillers for their knee pain (and if yes, frequency of use).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 25 (IBM). All data were visually inspected for normality using a Q-Q plot. To compare differences between the sexes in the patients who still experienced knee pain, the independent chi-square test for proportions was used. To compare KOOS Sports/Recreation scores, quality of life, and sports participation in the participants with and without knee pain at follow-up, we used independent-samples t test.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

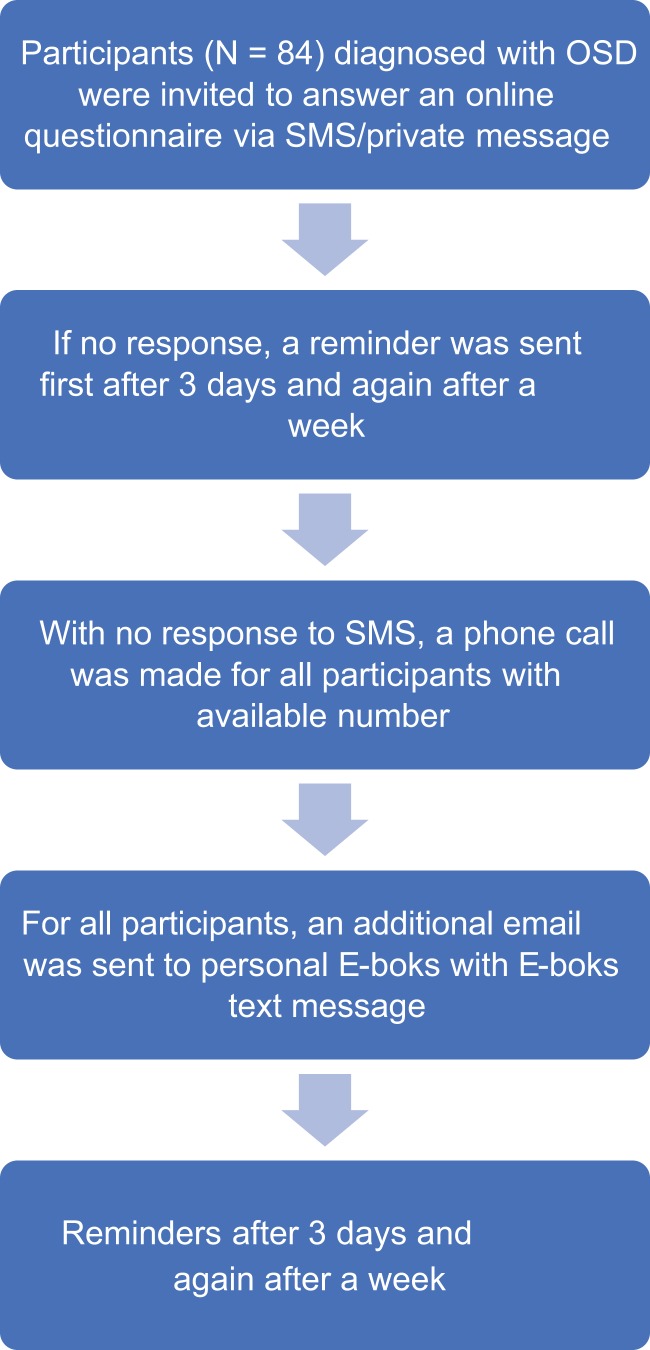

We contacted 84 eligible participants, and 43 (aged 14-55 years) responded; 12 (27.9%) were female, and 31 (72.1%) were male. The process of participant selection is displayed in Figure 1. Participants were a mean age of 12.6 ± 3.2 years when initially diagnosed with OSD, with a mean of 3.75 years from diagnosis to follow-up in 2018. The median pain duration in those with knee pain at follow-up was 90 months (interquartile range [IQR], 24-150 months). Of the respondents, 51.2% (n = 22) reported unilateral OSD, and 48.8% (n = 21) reported bilateral pain at the first diagnosis. None of those who had knee pain at follow-up reported receiving any additional knee diagnoses other than OSD. Overall, 16.3% (n = 7) of participants had pain in other regions, most commonly in the neck (n = 4) and lower back (n = 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing participant recruitment process. OSD, Osgood-Schlatter disease.

Knee Pain at Follow-up

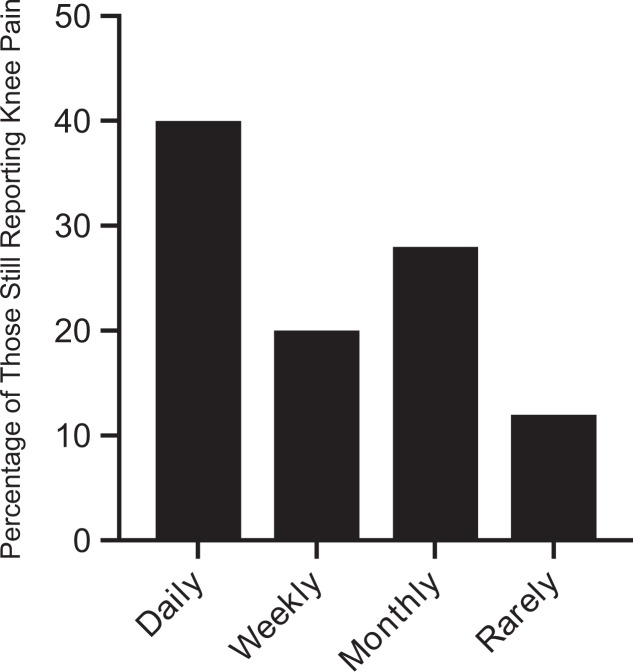

Of the respondents, 60.5% (n = 26) had OSD-related knee pain at follow-up. The median pain intensity on the VAS was 5 (IQR, 3-7). Figure 2 shows the frequency of knee pain. There were 54.8% (n = 17) of male and 75.0% (n = 9) of female participants who still had knee pain related to OSD (P = .22).

Figure 2.

Frequency (percentage) of knee pain at follow-up evaluated as rarely, monthly, weekly, and daily knee pain.

The majority (73.1%; n = 19) of participants with knee pain at follow-up reported pain below the knee and 34.6% at the tibia or at the patellar tendon, which are typically where OSD is experienced. Also, 46.2% (n = 12) had pain in 1 location around the knee. There were 53.8% (n = 14) who had knee pain in ≥2 locations; all of these patients had pain below the knee or at the tibia.

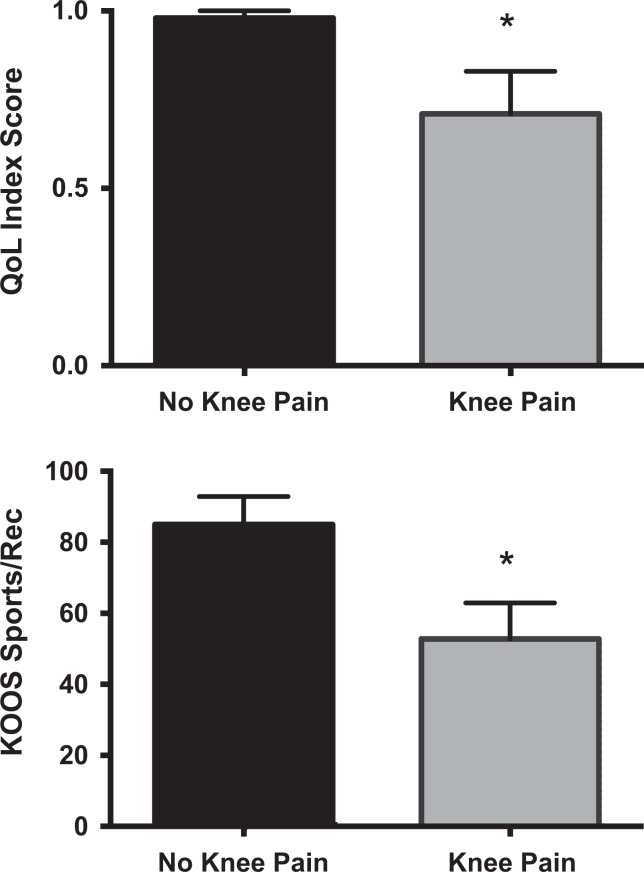

KOOS and HRQoL

There were significant differences in KOOS Sports/Recreation scores between those with and without knee pain (53 [95% CI, 42-63] vs 85 [95% CI, 76-94], respectively; P < .001) (Figure 3A). Those with knee pain also had significantly lower HRQoL (0.71 [95% CI, 0.57-0.84] vs 0.99 [95% CI, 0.97-1.00], respectively; P < .001) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Mean (A) health-related quality of life (QoL; youth version of EuroQol 5 dimensions 3 levels [EQ-5D-3L-Y]) and (B) Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) Sports/Recreation scores in those with and without knee pain at follow-up. *Significant difference between groups (P < .001).

Treatment

The majority of patients who experienced knee pain at follow-up reported receiving additional treatments for their pain, with 1 in 4 using painkillers for their knee pain at follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1.

Other Treatment and Painkiller Usagea

| Knee Pain at Follow-up | No Knee Pain at Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|

| Other treatment | 19 (73.1) | 9 (52.9) |

| Professional help | ||

| General practitioner | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Physical therapist | 7 (26.9) | 6 (35.3) |

| Chiropractor | 1 (3.8) | 1 (5.9) |

| Rheumatologist | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Kind of treatment | ||

| Strength exercises | 13 (50.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| RICE | 5 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Advice about sports participation | 6 (23.1) | 4 (23.5) |

| Stretching | 7 (26.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Knee sleeves | 13 (50.0) | 1 (15.9) |

| Painkillers | 7 (26.9) | 2 (11.8) |

| Surgery | 7 (26.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Other | 3 (11.5) | 2 (11.8) |

| Prior painkiller use | 18 (69.2%) | 7 (41.2%) |

| Frequency | ||

| Monthly | 2 (7.7) | 1 (5.9) |

| Weekly | 4 (15.4) | 2 (11.8) |

| More than once per week | 7 (26.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Almost daily | 5 (19.2) | 3 (17.6) |

| Current painkiller use | 7 (26.9) | — |

| Frequency | ||

| Monthly | 2 (28.6) | — |

| Weekly | 0 (0.0) | — |

| More than once per week | 2 (28.6) | — |

| Daily | 3 (42.9) | — |

aData are presented as n (%). RICE, rest, ice, compression, elevation.

Sports Participation

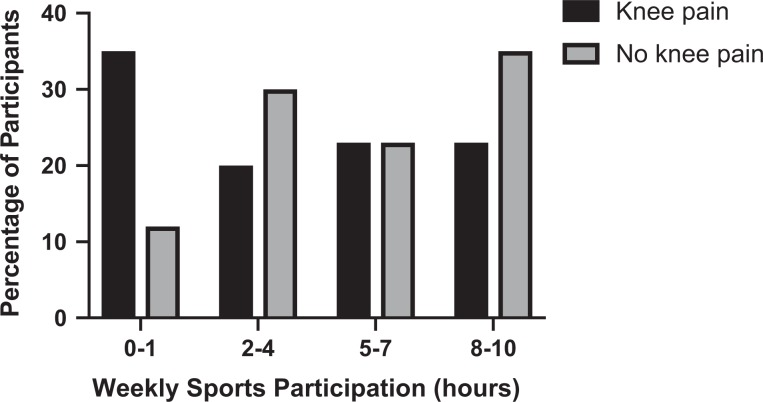

Of the patients who reported knee pain at follow-up, 73.1% (19 of 26) participated in sports, versus 82.4% (14 of 17) of the patients without knee pain at follow-up (P = .51). Furthermore, 53.8% (n = 14) of those with knee pain versus 35.3% (n = 6) of those without knee pain reduced their activity because of knee pain (P = .23). Figure 4 shows weekly sports participation at follow-up.

Figure 4.

Weekly sports participation evaluated in hours per week for those with and without knee pain at follow-up.

Participants With OSD Sequelae

Of all participants, 15 were adults (>18 years) when they were diagnosed with OSD sequelae at the orthopaedic department, indicating residual symptoms in adulthood. These patients reported originally receiving the diagnosis of OSD at 14.4 years of age, on average. Of these, 53.3% (n = 8) underwent surgery during follow-up, and 86.7% (n = 13) still had pain at follow-up.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study showed that over 60% of participants diagnosed with OSD at our orthopaedic department reported knee pain at long-term follow-up (median, 3.75 years; range, 2-6 years), despite OSD having previously been described as ceasing within 1 to 2 years.4,8,12,23 In fact, participants reported an OSD symptom duration of 90 months for those still experiencing knee pain, with 42.9% reporting daily knee pain. This risk of continued knee pain is slightly higher than that reported for patellofemoral pain (PFP) in adolescents, where a study by Rathleff et al17 showed that 40.5% of adolescents still experienced knee pain after 5 years. We believe that this difference in the incidence of continued knee pain between adolescents with PFP and OSD may be due to the study design, as we had a shorter follow-up period and a more selective (hospital) population. In the current study, patients with continued knee pain reported lower KOOS Sports/Recreation scores and HRQoL, and a higher proportion had stopped/reduced sports compared with those without knee pain (53.8% vs 35.3%, respectively). This study had a follow-up time between 1 and 6 years after the diagnosis of OSD, as OSD is described as a self-limiting disease lasting between 12 and 18 months.8

Participants reported pain at the tibial tuberosity/patellar tendon (ie, locations synonymous with OSD) but also in other locations. From this finding, it may be speculated that OSD-related pain becomes more diffuse over time; however, to truly examine this speculation about the pain trajectory, more studies with a prospective design and thorough clinical evaluation at follow-up are needed. The 90-month follow-up duration is long but is consistent with findings from other studies of OSD prognosis.13,19 Krause et al12 showed that 24% of patients still had symptoms at 9-year follow-up, and the majority were unable to kneel pain-free. Despite this finding being reported as early as 1990, and the documented literature of OSD-related sequelae in adulthood,15,24 few studies have tried to elucidate the long-term impact. As a result, OSD is still considered innocuous, with almost all literature reviews indicating that it will resolve in the majority of cases. This is problematic, as it may lead clinicians to underestimate the potential burden and impact of experiencing longstanding pain during adolescence. In the best cases, OSD may resolve quickly with no residual symptoms, but this study indicates that this may not be the case for all patients.

Lower Function and HRQoL in Participants With Knee Pain

The lower KOOS Sports/Recreation scores in those with knee pain at follow-up are in line with previous studies showing that patients with a history of OSD have reduced knee function.8 Those who were pain-free at follow-up had a mean KOOS score of 85 points, which is similar/slightly lower than young adults who are “recovered” from adolescent PFP (mean, 91 points).10

With regard to HRQoL, those with pain scored significantly lower as well. Patients without knee pain at follow-up scored similarly to previously reported values of healthy controls of a similar age without knee pain.18 It has previously been shown that OSD causes an initial decrease in HRQoL, which in turn improves over time after resolution.11 Together with the current data, this indicates that lower HRQoL in those with OSD-related pain may be a result of the presence of pain and associated limitations. This finding is in line with those of PFP, another common condition among adolescents, where patients with PFP have worse KOOS quality of life scores and HRQoL compared with pain-free controls.5

Effect of Pain on Physical Activity

More than one-third of patients with knee pain at follow-up exercised less than 1 hour per week, whereas only around 1 in 10 of those without knee pain did not exercise. According to the World Health Organization, children should be physically active 1 hour every day, and adults should be physically active 30 minutes every day.25 Based on the self-reported data, less than half of the group with knee pain at follow-up met recommended levels of activity during a week. This has important implications for treatment, as physical activity is essential for long-term health.25

In contrast to this, 1 in 5 of those with knee pain continued to participate in sports activity 8 to 10 hours every week. From the literature,6 we know that OSD primarily occurs in sports-active children and adolescents, which could be the reason why these patients still suffered from knee pain, which may need to be addressed or modified in future treatment. However, if clinicians recommend patients to cease activity until pain subsides, as is commonly prescribed in OSD, this may have serious implications on long-term physical activity if pain in some cases lasts several years, as documented in the current study. Clinicians should try and find alternate ways to keep patients with OSD active without worsening pain and symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is that it is based on a population diagnosed with OSD by an orthopaedic specialist, which increases the validity of the diagnosis. No clinical or ultrasonography examination was performed at follow-up to investigate patients’ self-reported symptoms further.12 Therefore, despite participants reporting pain in OSD-related areas (tibial tubercle and patellar tendon), it could not be confirmed that the pain is not related to other subsequently developed conditions. Some of the included participants were seen in the orthopaedic department as adults because of the sequelae of OSD, which may influence the recall of specific details regarding the onset of their knee pain (eg, age of onset or painkiller frequency during adolescence). The low response rate (51.2%) may indicate a response bias and calls into question the generalizability of the proportion reporting knee pain at follow-up; these patients may have been at the “worst end” of the spectrum. Further, because of the small sample size, we may have been underpowered for some analyses.

Clinical Implications

In some cases, a history of OSD may be associated with long-term pain and impact on sports. Further prospective research is needed to validate this finding, including studies with a clinical follow-up evaluation to determine if pain is indeed related to current OSD. However, we previously demonstrated in a follow-up study that very few adolescents without knee pain during adolescence developed knee pain at 5-year follow-up,17 which would make it unlikely that the high proportion reporting knee pain at follow-up in the current study is unrelated to their history of OSD. These findings may have important implications for the evidence-based information that patients are given in the secondary care sector. Our results indicate that some patients may experience knee pain and functional limitations for extended periods of time. This is important information helping to guide realistic patient expectations about the long-term prognosis and impact of this common pain complaint.

Conclusion

In the current study, more than half of the participants diagnosed with OSD continued to experience knee pain at approximately 4 years after diagnosis. As a history of OSD appears to be associated with a long-term impact of function and quality of life, future studies need to further investigate the cause of ongoing pain in patients with a history of OSD.

Footnotes

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Science Ethics Committee of the Northern Jutland Region in Denmark.

References

- 1. Burström K, Egmar A, Lugnér A, et al. A Swedish child-friendly pilot version of the EQ-5D instrument: the development process. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21( 2):171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cairns G, Owen T, Kluzek S, et al. Therapeutic interventions in children and adolescents with patellar tendon related pain: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Çakmak S, Tekin L, Akarsu S. Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(1):135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Circi E, Atalay Y, Beyzadeoglu T. Treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease: review of the literature. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coburn SL, Barton CJ, Filbay SR, et al. Quality of life in individuals with patellofemoral pain: a systematic review including meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2018;33:96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Lucena GL, dos Santos Gomes C, Guerra RO. Prevalence and associated factors of Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in a population-based sample of Brazilian adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flowers MJ, Bhadreshwar DR. Tibial tuberosity excision for symptomatic Osgood-Schlatter disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(3):292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gholve PA, Scher DM, Khakharia S, et al. Osgood Schlatter syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(1):44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holden S, Straszek CL, Rathleff MS, et al. Young females with long-standing patellofemoral pain display impaired conditioned pain modulation, increased temporal summation of pain, and widespread hyperalgesia. Pain. 2018;159(12):2530–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaya DO, Toprak U, Baltaci G, et al. Long-term functional and sonographic outcomes in Osgood-Schlatter disease. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(5):1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krause BL, Williams JP, Catterall A. Natural history of Osgood-Schlatter disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(1):65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kujala UM, Kvist M, Heinonen O. Osgood-Schlatter’s disease in adolescent athletes: retrospective study of incidence and duration. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(4):236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ortqvist M, Iversen MD, Janarv P, et al. Psychometric properties of the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Children (KOOS-Child) in children with knee disorders. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(19):1437–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pihlajamäki HK, Visuri TI. Long-term outcome after surgical treatment of unresolved Osgood-Schlatter disease in young men: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(suppl 1, pt 2):258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rathleff CR, Olesen JL, Roos EM, et al. Half of 12-15-year-olds with knee pain still have pain after one year. Dan Med J. 2013;60(11):A4725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rathleff MS, Holden S, Straszek CL, et al. Five-year prognosis and impact of adolescent knee pain: a prospective population-based cohort study of 504 adolescents in Denmark. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e024113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Olesen JL, et al. Is knee pain during adolescence a self-limiting condition? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross MD, Villard D. Disability levels of college-aged men with a history of Osgood-Schlatter disease. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(4):659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan A, Strauss VY, Protheroe J, et al. Epidemiology of paediatric presentations with musculoskeletal problems in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2003;12(12):1500–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vreju F, Ciurea P, Rosu A. Osgood-Schlatter disease: ultrasonographic diagnostic. Med Ultrason. 2010;12(4):336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wall EJ. Osgood-Schlatter disease: practical treatment for a self-limiting condition. Phys Sportsmed. 1998;26(3):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weiss JM, Jordan SS, Andersen JS, et al. Surgical treatment of unresolved Osgood-Schlatter disease: ossicle resection with tibial tubercleplasty. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(7):844–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 25. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/global-PA-recs-2010.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2019. [PubMed]