Abstract

Introduction

New fluorinated diaryl ethers and bisarylic ketones were designed and evaluated for their anti-inflammatory effects in primary macrophages.

Methods

The synthesis of the designed molecules started from easily accessible and versatile gem-difluoro propargylic derivatives. The desired aromatic systems were obtained using Diels–Alder/aromatization sequences and this was followed by Pd-catalyzed coupling reactions and, when required, final functionalization steps. Both direct inhibitory effects on cyclooxygenase-1 or -2 activities, protein expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-II and the production of prostaglandin E2, the pro-inflammatory nitric oxide and interleukin-6 were evaluated in primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharide. Docking of the designed molecules in cyclooxygenase-1 or -2 was performed.

Results

Only fluorinated compounds exerted anti-inflammatory activities by lowering the secretion of interleukin-6, nitric oxide, and prostaglandin E2, and decreasing the protein expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in mouse primary macrophages exposed to lipopolysaccharide, as well as cyclooxygenase activity for some inhibitors with different efficiencies depending on the R-groups. Docking observation suggested an inhibitory role of cyclooxygenase-1 or -2 for compounds A3, A4 and A5 in addition to their capacity to inhibit nitrite, interleukin-6, and nitric oxide synthase-II and cyclooxygenase-2 expression.

Conclusion

The new fluorinated diaryl ethers and bisarylic ketones have anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages. These fluorinated compounds have improved potential anti-inflammatory properties due to the fluorine residues in the bioactive molecules.

Keywords: Fluorine, Diaryl ethers, Macrophages, Cyclooxygenase, Inflammation

Introduction

Diaryl ethers are key scaffolds present in many natural or synthetic organic molecules, which are often used in medicinal chemistry [1]. Fenoprofen for instance is one of the synthetic diarylethers [2] with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antirheumatic effects [3]. More precisely, it is a derivative of 2-aryl propanoic acids, which is an important class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, naproxen and fenoprofen.

Moreover, benzophenone analogues, such as ketoprofen, recently have been reported also as potent anti-inflammatory agents by inhibiting prostaglandin (PG) production [4, 5]. It has been shown that benzoylphenyl acetic acid for instance has anti-inflammatory activity by decreasing the volume of paw edema in treated rats [6].

On the other hand, the introduction of fluorine into organic molecules may cause profound pharmacological effects by improving the activity and selectivity of the bioactive molecules [7]. The utility of fluorine in the design of drugs results mainly from its ability to modify some functional activities, such as increasing lipophilicity [8] and extending its bioavailability [9]. Moreover, carbon forms stronger bond with fluorine (CF)n, with a higher oxidative and thermal stability than a carbon–hydrogen bond [10]. The CF2 unit for instance is generally considered as a bioisostere of the oxygen atom or of a carbonyl group [11].

We therefore synthesized new gem-difluorobisarylic derivatives and evaluated their anti-inflammatory effects. We first investigated their effects on PGE2 production in mouse primary macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and their anti-cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and -2 activities. We next studied their effects on the production of the pro-inflammatory nitric oxide (NO) and interleukin (IL)-6 and the expression of NO synthase-II (NOS-II) and COX-2.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of bisarylic derivatives

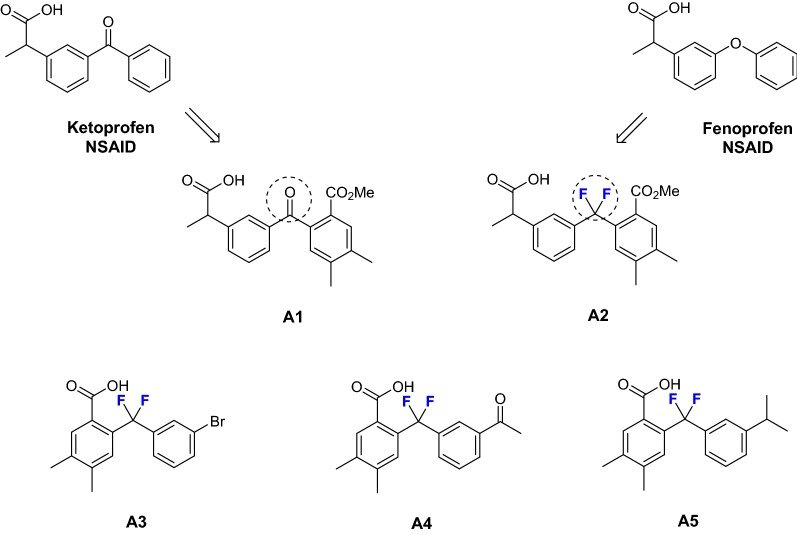

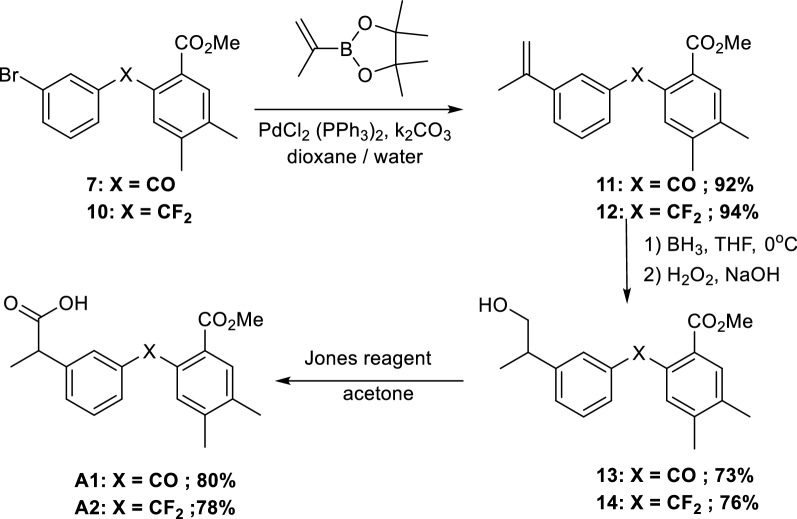

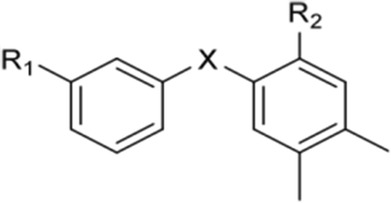

Based on our previous study [12], five bisarylic compounds A1 to A5 were designed as indicated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Design of target molecules

In our strategy, the gem-difluoro unit has been chosen as a mimic of either the ether oxygen (fenoprofen series) or of a carbonyl group (ketoprofen series). First, two phenylpropionic acid derivatives A1 (as a non-fluorinated reference) and the corresponding gem-difluoro derivative A2 were proposed as analogues of fenoprofen and ketoprofen. The comparison of the inhibitory activities of compounds A1 and A2 would allow establishing the impact of fluorine atom on the efficiency of these compounds. On the other hand, three other derivatives A3, A4, and A5 were designed as simplified benzoic acid-type derivatives, with three different substituents in meta position on the second aromatic ring (Scheme 1).

Synthetic procedures

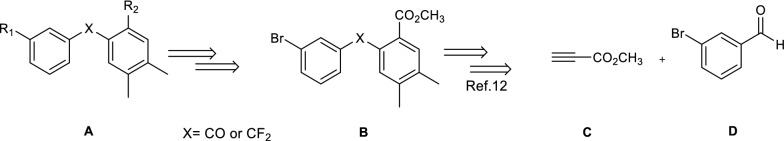

All these molecules were synthesized from bromo intermediates B (Scheme 2, Table 1) and were tested for their anti-inflammatory activity.

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis for the preparation of compounds A

Table 1.

Preparation of five bisarylic compounds

| Compound | X | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | C=O |

|

–CO2CH3 |

| A2 | CF2 |

|

–CO2CH3 |

| A3 | CF2 | Br | –CO2H |

| A4 | CF2 | –COCH3 | –CO2H |

| A5 | CF2 | –CH(CH3)2 | –CO2H |

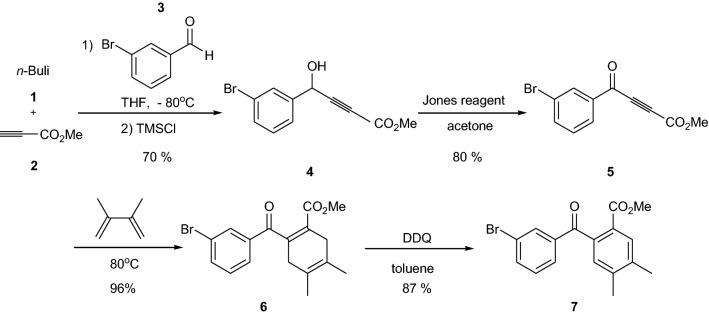

Synthesis of key intermediates 7 and 10

Addition of the lithium salt of compound 2 to 3-bromobenzaldehyde 3 at low temperature (− 80 °C) gave propargyl alcohol 4 in 70% yield. After oxidation with Jones reagent, propargylic ketone 5 was isolated in 80% yield. Then, Diels–Alder reaction and DDQ aromatization provided the intermediate 7 with a good yield for both steps (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the non-fluorinated key intermediate 7

After treatment of ketone 5 by DAST, compound 8 was obtained in 71% yield. Similarly, Diels–Alder reaction and DDQ aromatization proceeded well by giving the fluorinated intermediate 10 with excellent yields (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the fluorinated key intermediate 10

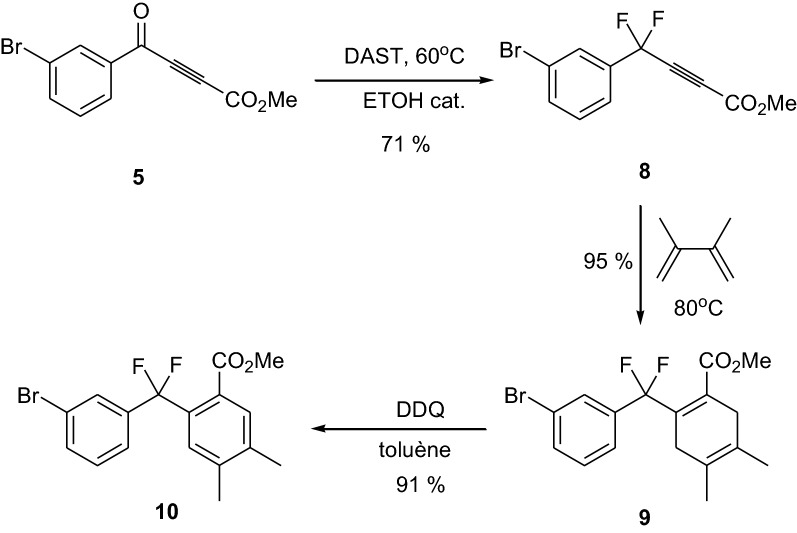

Preparation of compounds A1 and A2

Starting from the key scaffolds 7 and 10, Suzuki–Miyaura couplings, with boronic acid, afforded biphenyl type compounds 11 and 12 in 92 and 94% yield, respectively. Then, hydroboration to 13 and 14, followed by oxidation with Jones reagent led to the desired analogues A1 and A2 in good yields (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of derivatives A1 and A2

Preparation of compounds A3, A4, and A5

Starting from intermediates 10 and 12, reduction with LiBEt3H furnished alcohols 15 and 16 respectively, then oxidation by Jones reagent gave the desired acid A3. However, in the case of 16, an unexpected cleavage of the double bond occurred, affording acid A4. Using the same gem-difluoro intermediate 12, catalytic hydrogenation to 17, followed by reduction and oxidation afforded the desired derivative A5 in good yields (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of gem-diaryl derivatives A3, A4, and A5

Biological activities

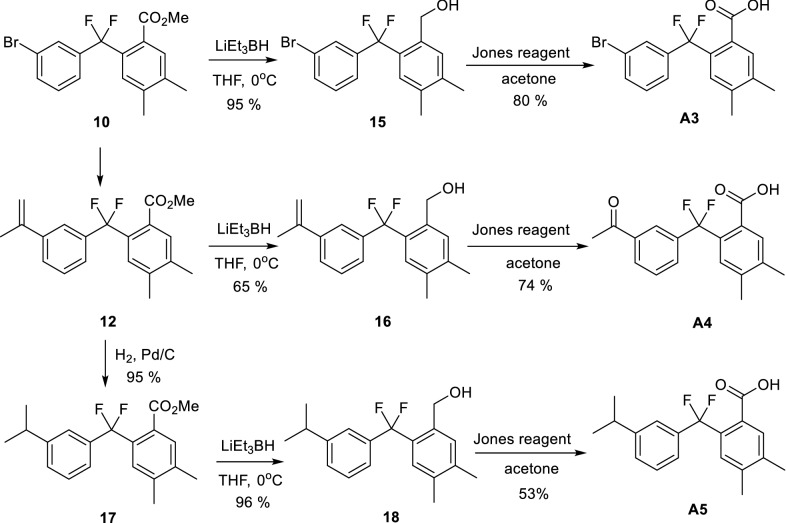

We investigated the effects of these derivatives on inflammation in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) by first evaluating their capacity to decrease LPS-dependent increase of PGE2 secretion and COX-2 expression. Compound A1 (non-fluorinated) and compound A2 (fluorinated) effects were compared to evaluate the importance of the fluorine atom. Only compound A2 inhibited significantly in a dose-dependent manner the secretion of PGE2 (Fig. 1a) (IC50 = 16.5 ± 8.9 µM) with no effect on COX-2 expression (Fig. 1c) supporting the importance of fluorine in inhibiting PGE2 production.

Fig. 1.

Effects of the gem-difluorobisarylic derivatives on PGE2 production and COX-2 expression in activated macrophages. BMDM were treated with 6 increasing concentrations, prior to the addition of 10 ng/mL LPS for 24 h. PGE2 secretion was measured and expressed as percentage of LPS for a compounds A1 and A2 and b compounds A3, A4 and A5. Corresponding IC50 fitting curves are shown. c, d COX-2 and β-actin expression in basal and LPS-treated BMDM with 50 µM of all compounds. Results are obtained from the same blot. Protein bands for basal or LPS-treated macrophages, in the absence of inhibitors, as shown in c and d, are identical for illustration purpose. Dose–response effect of compounds e A4 and f A5 on COX-2 expression. β-actin was used as loading control. Ratio of COX-2/β-actin was calculated after densitometry analysis using ImageJ software. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4), *p < 0.05 versus LPS (One-way Anova followed by the Dunnett’s test)

In parallel, we compared the inhibitory effects of compounds A3, A4 and A5, which are all fluorinated but present differences in R1 group (Table 1). Compound A3 is the bromine intermediate obtained in the synthetic reaction of compound A5. Compound A4 is a ketone intermediate obtained unexpectedly with good yield during the synthesis of compound A5. Compounds A3, A4 and A5 have the carboxyl group attached to the benzene ring in the ortho position relative to CF2 group.

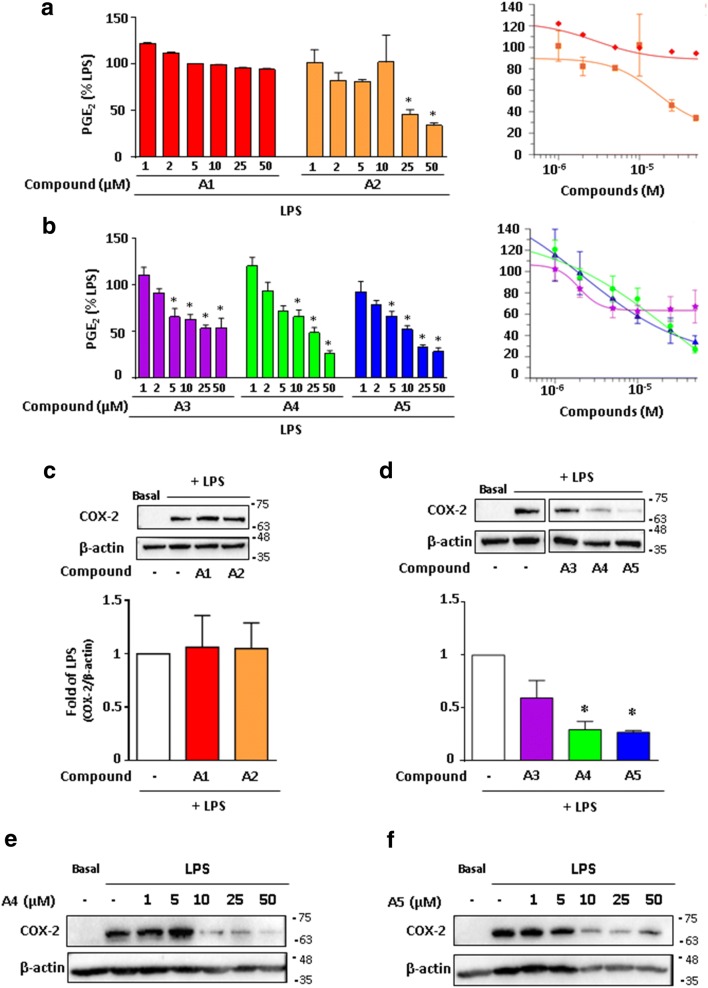

Figure 1b showed a dose response effect of these derivatives on PGE2 secretion, in which compounds A4 and A5 significantly decreased PGE2 secretion at 25 and 50 µM with IC50 of 28.1 ± 22.8 and 22.4 ± 21.5 µM, respectively. Compound A3 did not show a strong inhibition at similar concentrations. Under these conditions, only compounds A4 and A5 significantly downregulated COX-2 expression (Fig. 1d). Further analysis showed a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on COX-2 expression for compounds A4 and A5 (Fig. 1e and f, respectively). Thus, the nature of R groups in compounds A4 and A5 is important for their inhibitory effect on COX-2 expression and consequently PGE2 production. We next addressed the question whether COX activity was inhibited. We performed COX-1 activity using Human Embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells stably overexpressing COX-1. Cells were treated with all compounds at 10 and 50 µM and PGE2 was measured after the addition of arachidonic acid (AA). The results showed that compound A5 had the maximal inhibitory effect on COX-1 activity with more than 80% inhibition at 50 µM (Fig. 2a) with an IC50 of 5.2 µM.

Fig. 2.

Effects of the gem-difluorobisarylic derivatives on COX-1 and COX-2 activity. a COX-1 activity. HEK-293 cells overexpressing recombinant COX-1 were treated with 10 and 50 µM of all compounds for 45 min prior to the addition of 10 µM arachidonic acid (AA). PGE2 was measured. b COX-2 activity. BMDM cells were treated with 10 µM of ASA for 30 min, washed, and 10 ng/mL LPS was added for 24 h to induce COX-2. Cells were further incubated with 10 and 50 µM of each compound prior to the addition of 10 µM AA. PGE2 was measured. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4), *p < 0.05 versus AA for COX-1 activity, and versus LPS + ASA + AA for COX-2 activity (One-way Anova followed by the Dunnett’s test)

COX-2 activity was also assessed on BMDM treated for 30 min with aspirin to inhibit basal COX activity prior to the addition of 10 ng/mL LPS for 24 h which induces COX-2. These cells were then treated with 10 and 50 µM of derivatives and further incubated with AA. PGE2 production revealed that compound A5 inhibited strongly COX-2 activity with an IC50 of 13.3 µM, whereas moderate effect was observed for compounds A2, A3 and A4 (Fig. 2b). Indeed, the assay used for COX-2 activity cannot exclude an effect on mPGES-1.

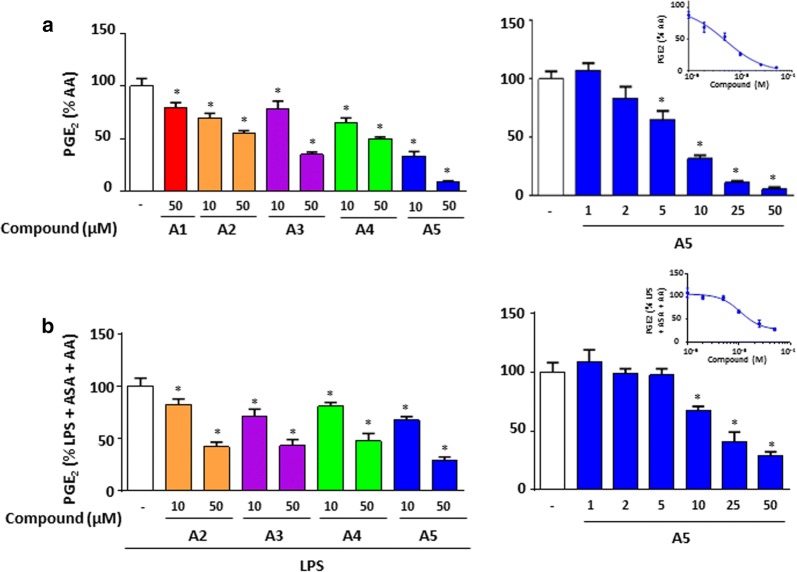

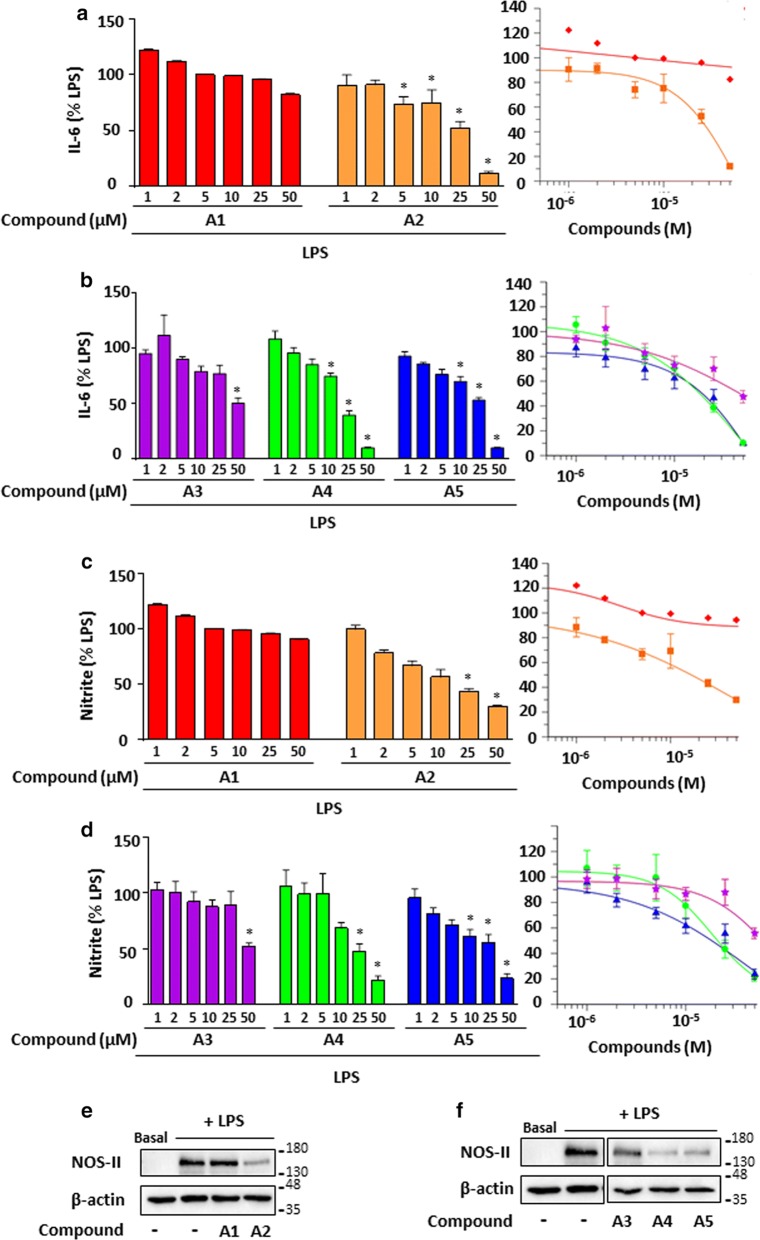

In parallel, we assessed the effect of these compounds on the production of IL-6 and NO measured by its breakdown product nitrite. Figure 3 showed a dose response inhibition of compounds A2 (Fig. 3a, c), A4 and A5 (Fig. 3b, d) for both IL-6 and NO secretion. IC50 are presented in Table 2 and were significant for compounds A4 and A5.

Fig. 3.

Effects of the gem-difluorobisarylic derivatives IL-6 and nitrite, and NOS-II expression. BMDM were treated with 6 increasing concentrations of all compounds prior to the addition of 10 ng/mL LPS for 24 h. IL-6 and NO production was measured and expressed as percentage of LPS for a, c compounds A1 and A2, and b, d, compounds A3, A4 and A5, respectively. Corresponding IC50 fitting curves are shown. e, f NOS-II and β-actin expression in basal and LPS-treated BMDMs with 50 µM of all compounds. Results are obtained from the same blot. Protein bands for basal or LPS-treated in macrophages in the absence of inhibitors, as shown in e and f, are identical for illustration purpose. β-actin was used as loading control. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4), *p < 0.05 versus LPS (One-way Anova followed by the Dunnett’s test)

Table 2.

In vitro inhibition activity of compounds A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5 on inflammatory mediators in macrophages

| Compounds | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | NO | |

| A1 | ND | ND |

| A2 | 64.5 ± 21.1a | 45.2 ± 24.6 |

| A3 | 60 ± 60.2 | ND |

| A4 | 51.2 ± 17.4 | 18.5 ± 2.7 |

| A5 | 82.6 ± 24.0 | 40.9 ± 25.4 |

| Fenoprofen | 300 ± 100 | 43.8 ± 39.2 |

ND not determined

aMean ± SEM

NOS-II is the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase, and is responsible for the production of the measured NO. For this, NOS-II protein expression was analyzed in LPS-stimulated BMDM, treated with 50 µM of bisarylic derivatives for 24 h. Results revealed that the fluorinated compounds A2, A4 and A5 inhibited NOS-II expression in parallel to NO production (Fig. 3e, f).

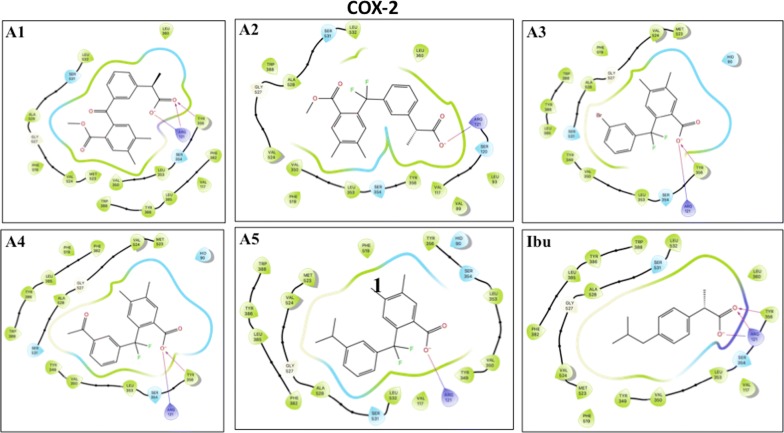

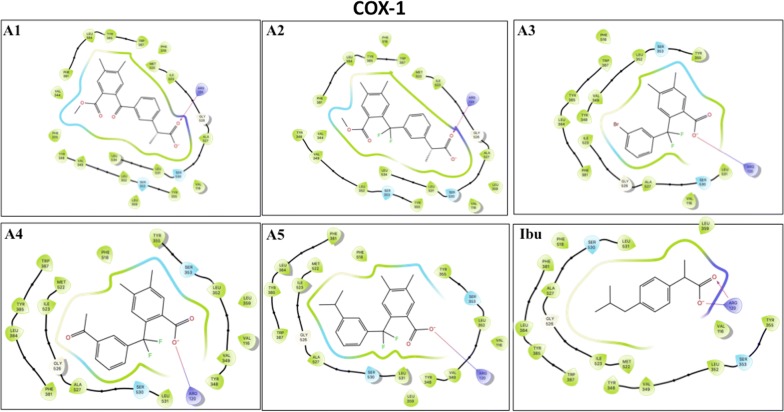

Molecular docking

We finally carried out model analysis of the inhibitors with ovine COX-1 [13] and murine COX-2 [14], to examine how these compounds dock with the active sites of the enzymes and to determine the amino acids involved in the interaction with the compounds. Ibuprofen docked into the hydrophobic cavity of COX-2 formed by Arg121, Tyr356, Ser354, Leu353, Val350 and Tyr349, where the carboxyl group of ibuprofen interacts with Arg121 and Tyr356 by a salt bridge and a hydrogen bond. The compounds A3, A4 and A5 were docked near Arg121, similarly to ibuprofen. Compounds A3 and A4 showed interaction with Tyr356 (Fig. 4). The binding scores of compounds A3, A4 and A5 (− 7.7 kcal/mol, − 7.7 kcal/mol and − 7.5 kcal/mol respectively) are comparable to ibuprofen (Table 3). Furthermore, the difluoromethyl group present in these compounds, which introduces a strong electrostatic field in this hydrophobic pocket, would be in favor the interaction with Arg121. Compounds A1 and A2, even though they occupy the same active pocket, interact with Arg121 through the carboxylate group with less binding energy, have a bulky side chains that negatively would affect the stability of these molecules in the hydrophobic pocket. For COX-1, ibuprofen docked into the hydrophobic pocket composed of the amino acids Arg120, Tyr355, Ser353, Leu352, Val349, Tyr348, Val116, Leu531, Ser530, Ala527, Gly526 and Ile523. All compounds docked in the same active hydrophobic pocket of COX-1. Only Arg120 interacts with the carboxylate group by a salt bridge (Fig. 5). Similarly, to ibuprofen, compounds A2, A3, A4 and A5 showed a moderate binding energy compared to ibuprofen (− 7 kcal/mol and − 7.8 kcal/mol respectively, Table 3) whereas compound A1 showed the lowest binding energy, which is compatible with biological activities.

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional pose of compounds A1 to A5 and Ibuprofen inside the binding pocket of mouse COX-2 as crystallized by [13]. Ligand-receptor interactions as highlighted by Maestro (Shrodinger, LLC). Ligands are represented in stick, and amino acids within the binding pocket are labeled. An arrow represents the H-bonds between an amino acid and ligand groups. A line shows a potential salt bridge between two charged groups

Table 3.

Comparison of COX-1 and COX-2 molecular docking data

| Compound | COX-1 kcal/mol | COX-2 kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | − 6.5 | − 6.6 |

| A2 | − 7 | − 6.7 |

| A3 | − 7 | − 7.7 |

| A4 | − 7 | − 7.7 |

| A5 | − 7 | − 7.5 |

| Ibuprofen | − 7.8 | − 7.7 |

Fig. 5.

Two-Dimensional pose of compounds A1 to A5 and Ibuprofen inside the binding pocket of human COX-1 as crystallized by [14]. Ligand receptor interactions were evaluated for COX-1 as described in legend for Fig. 4

More analyses are required to fully understand the key role of the fluorine atoms on the biological activity of these molecules. However, to explain these results, it is possible that the bulky and lipophilic CF2 group could fit better in the pocket of these proteins than the carbonyl of ketoprofen or the oxygen atom of fenoprofen. Further, in the case of compounds A3, A4 and A5 it can also increase the acidity of the CO2H in ortho position.

Conclusion

In conclusion, five bisarylic derivatives were prepared and tested in comparison with fenoprofen. This type of compounds is endowed with certain anti-inflammatory activities in mouse primary macrophages with a significant difference between the fluorinated analogues and the non-fluorinated one, showing the importance of the CF2 group. All fluorinated derivatives blocked PGE2, nitrite and IL-6 production in activated macrophages. Derivatives A4 and A5 showed additional strong inhibition of COX-2 and NOS-II expression. In addition, derivatives A3, A4 and A5 showed better anti-inflammatory activities than the other derivatives, with compound A5 having COX-1 and COX-2 direct inhibitory activities. Molecular docking of the compounds COX-1 and COX-2 are in support of the biological activity.

Methods

Chemistry experimental part

Reactions were carried out as described previously and monitored as described by 19F NMR and by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) [15]. Yields refer to chromatographically and spectroscopically (1H, 13C, and 19F NMR) homogeneous materials. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra have been recorded as previously described [15]. Mass spectral analyses have been performed at the Centre Régional de Mesures Physiques de l’Ouest (CRMPO) in Rennes (France).

Synthesis of methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4-hydroxybut-2-ynoate 4

To a solution of methylpropiolate (2.6 mL, 29.20 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) cooled at − 90 °C and set under nitrogen, n-BuLi (11.4 mL, 2.5 M, 1.2 equiv.) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at T − 80 °C before the dropwise addition of a solution of 3-bromobenzaldehyde (4 g, 21.60 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL). After stirring for additional 20 min at the same temperature, TMSCl (7 mL, 55.00 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture that was stirred for 1 h at − 80 °C and then left to rise at room temperature while continuous stirring for additional 2 h. The mixture was treated with concentrated solution of NH4Cl, extracted with ethyl acetate (3 times), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated by evaporating the solvent. Alcohol 4 was isolated over silica gel by column chromatography.

Synthesis of methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4-oxobut-2-ynoate 5

To alcohol 4 (2.1 g, 7.46 mmol) in acetone (18 mL) was added dropwise under magnetic stirring at room temperature, a concentrated (5.4 M) solution of Jones reagent until disappearance of the starting material (TLC analysis). After addition of isopropanol (5 equiv.), the reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuum. After purification by chromatography on silica gel, ketone 5 was obtained.

Synthesis of methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4,4-difluorobut-2-ynoate 8

To propargylic ketone 5 (350 mg, 1.31 mmol) were added one drop of 95% ethanol and DAST (1.05 mL, 7.96 mmol, 6 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 7 h. After coming back to room temperature and hydrolysis, the reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 times). The organic layers were separated, washed with water (3 times), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum. After purification by chromatography on silica gel, fluorinated compound 8 was obtained.

Synthesis of methyl 2-(3-bromobenzoyl)-4,5-dimethylcyclohexa-1,4-dienecarboxylate 6 and methyl 2-((3-bromophenyl) difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylcyclohexa-1,4-dienecarboxylate 9

Difluoro propagylic ester (1.54 mmol) and 2,3-dimethyl-1,3-butadiene (14 equiv.) were refluxed neat at nearly 80 °C. The reaction was controlled by 19F NMR after 5 h and was stopped by that time. Finally, the unreacted butadiene was evaporated. After purification by column chromatography on silica gel, cyclohexadienes 6 and 9 were isolated.

Synthesis of methyl 2-(3-bromobenzoyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 7 and methyl 2-((3-bromophenyl) difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 10

A solution of the cyclohexadiene (2.18 mmol) and DDQ (1.2 equiv.) in toluene (7 mL) was stirred at 42 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was filtered on silica gel and the residues were washed with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo and compounds 7 and 10 were isolated by chromatography on silica gel.

Synthesis of methyl 4,5-dimethyl-2-(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl) benzoyl) benzoate 11 and methyl 2-(difluoro(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl) phenyl) methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 12

A solution of bromo-ester (1.74 mmol), isopropenylboronic acid pinacol ester (2 equiv.), palladium dichlorobistriphenylphosphine (5% mol) and potassium carbonate (2 equiv.) in a 5/1 mixture of dioxane and water (15/3 mL) was stirred at 90 °C for 20 h. The reaction mixture was extracted by ethyl acetate (3 times). The combined organic phases were washed with water, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. After purification by chromatography on silica gel, the compounds 11 and 12 were isolated.

Synthesis of methyl 2-(3-(1-hydroxypropan-2-yl)benzoyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 13 and methyl 2-(difluoro(3-(1-hydroxypropan-2-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 14

To the alkene (0.72 mmol) in anhydrous THF (5 mL) was added, dropwise under magnetic stirring and under N2 at 0 °C, a solution of BH3 in THF (5.5 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. After 24 h, the mixture was oxidized by addition of H2O2 30% (4.4 equiv.) and NaOH 3 M (4.4 equiv.) and was stirred for 2 h. The organic phase was separated, while the aqueous phase was extracted by ethyl acetate. The organic fractions were collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. After purification by flash chromatography on silica gel, alcohols 13 and 14 were isolated.

Synthesis of (2-((3-bromophenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol 15, (2-(difluoro(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol 16 and (2-(difluoro(3-isopropylphenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol 18

To the ester (0.27 mmol) in anhydrous THF (4 mL) was added, dropwise under magnetic stirring and under N2 at 0 °C, a 1 M solution of LiEt3BH in THF (2.5 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 15 min and then quenched by addition of a saturated NH4Cl solution. The organic phase was separated, while the aqueous phase was extracted by ethyl acetate. The organic fractions were collected, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. After purification by flash chromatography on silica gel, alcohols 15, 16 and 18 were isolated.

Synthesis of methyl 2-(difluoro(3-isopropylphenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate 17

To a solution of 12 (498 mg, 1.51 mmol) in AcOEt (15 mL), was added 50 mg of palladium-charcoal catalyst (10%). The mixture was stirred at room temperature under hydrogen atmosphere. After 2 h, it was filtered and compound 17 was obtained, after purification on silica gel.

The physicochemical properties and the spectral data of intermediates 4–18 are presented in the Tables 4 and 5, respectively and in Tables 6 and 7 for the synthesized bisarylic derivatives A1 to A5.

Table 4.

The physicochemical properties of intermediates 4–18

| Compound | IUPAC Name |

Aspect | Mass of the starting material | Mass of the product | Rf value (PE:EtOAc) | m.p. (oC) | % yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4-hydroxybut-2- ynoate | Yellow oil | 4 g | 3.9 g | 0.30 (8:2) | – | 70 |

| 5 | Methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4-oxobut-2-ynoate | Yellow solid | 2.10 g | 1.59 g | 0.40 (9:1) | 102–104 | 80 |

| 6 | Methyl 2-(3-bromobenzoyl)-4,5-dimethylcyclohexa-1,4-dienecarboxylate | Yellow solid | 410 mg | 560 mg | 0.43 (9:1) | 100–102 | 96 |

| 7 | Methyl 2-(3-bromobenzoyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | Yellow solid | 937 mg | 810 mg | 0.34 (9:1) | 122–124 | 87 |

| 8 | Methyl 4-(3-bromophenyl)-4,4-difluorobut-2-ynoate | Colorless oil | 350 mg | 270 mg | 0.44 (9:1) | – | 71 |

| 9 | Methyl 2-((3-bromophenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylcyclohexa-1,4-dienecarboxylate | White solid | 757 mg | 925 mg | 0.44 (9:1) | 72–74 | 95 |

| 10 | Methyl 2-((3-bromophenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | Yellow solid | 808 mg | 731 mg | 0.51 (9:1) | 60–62 | 91 |

| 11 | Methyl 4,5-dimethyl-2-(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl)benzoyl)benzoate | White solid | 782 mg | 640 mg | 0.34 (9:1) | 82–48 | 92 |

| 12 | Methyl 2-(difluoro(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | Yellow oil | 640 mg | 539 mg | 0.35 (9:1) | – | 94 |

| 13 | Methyl 2-(3-(1-hydroxypropan-2-yl)benzoyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | Yellow oil | 400 mg | 309 mg | 0.42 (7:3) | – | 73 |

| 14 | Methyl 2-(difluoro(3-(1-hydroxypropan-2-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | Yellow oil | 240 mg | 192 mg | 0.36 (7.5:2.5) | – | 76 |

| 15 | (2-((3-bromophenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol | White solid | 100 mg | 88 mg | 0.26 (9:1) | 62–64 | 95 |

| 16 | (2-(difluoro(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol | Yellow oil | 148 mg | 88 mg | 0.37 (8:2) | – | 65 |

| 17 | Methyl 2-(difluoro(3-isopropylphenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoate | White solid | 498 mg | 476 mg | 0.72 (9:1) | 116–118 | 95 |

| 18 | (2-(difluoro(3-isopropylphenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methanol | White solid | 294 mg | 260 mg | 0.69 (9:1) | 80–82 | 96 |

Table 5.

Spectral data of intermediates 4–18

| Compound | 1H NMR | 13C NMR | 19F NMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.56 (m, 1H), 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.18 (m, 1H), 5.44 (s, 1H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 3.64 (br. s, 1H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 153.7, 140.5, 131.8, 130.2, 129.6, 125.1, 122.7, 86.0, 77.6, 63.2, 53.0 | |

| 5 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 8.02 (t, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz), 7.86 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.9, 1.7 and 1.0 Hz), 7.61 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.9, 1.7 and 1.0 Hz), 7.23 (t, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 3.73 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 173.6, 151.4, 137.0, 136.1, 131.3, 129.5, 127.4 (3C), 79.7, 78.3, 52.6. | |

| 6 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 8.01 (t, 1H, J = 1.9 Hz), 7.80 (m, 1H), 7.68 (m, 1H), 7.33 (t, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.53 (s, 3H), 2.97–2.98 (m,4H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 197.1, 165.9, 146.8, 137.0, 136.0, 131.2, 130.3, 127.1, 125.6, 123.1, 123.0, 120.6, 51.8, 36.5, 32.6, 18.2, 17.8 | |

| 7 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.89 (t, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz). 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.13 (s, 1H), 3.61 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.33 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 195.9, 166.3, 142.1, 139.3, 138.8, 138.6, 135.6, 131.8, 131.1, 129.9, 128.8, 127.7, 126.4, 122.7, 52.0, 19.9, 19.6 | |

| 8 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.55 (m, 1H), 7.49 (m, 1H), 7.26 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.76 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 152.1 (t, 4J = 2.4 Hz), 136.2 (t, 2J = 27.5 Hz), 134.5 (t, 4J = 1.6 Hz), 130.4, 128.3 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 123.9 (t, 3J = 4.9 Hz), 122.7, 110.4 (t, 1J = 236.3 Hz), 78.4 (t, 3J = 5.9 Hz), 76.5 (t, 2J = 43.7 Hz), 53.4 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: -80.06 (s) |

| 9 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.23 (m, 1H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 2.86 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.50 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.57 (s, 3H), 1.52 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 170.3, 137.7 (t, 2J = 28.4 Hz), 133.2, 130.0, 129.9 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 128.9 (t, 3J = 5.9 Hz), 128.8 (t, 2J = 25.4 Hz), 124.5 (t, 4J = 5.6 Hz), 122.5, 121.6, 121.2, 119.4 (t, 1J = 244.4 Hz), 52.1, 35.8, 31.6, 18.0, 17.7 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: − 93.06 (s) |

| 10 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.62 (s, 1H), 7.54 (m, 1H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 3.65 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.33 (s, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 168.2, 140.1 (t, 2J = 28.3 Hz), 140.0, 139.1 (t, 4J = 1.3 Hz), 132.8 (t, 4J = 2.7 Hz), 131.9 (t, 2J = 26.9 Hz), 131.1, 129.7, 129.0 (t, 3J = 5.3 Hz), 128.5 (t, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 128.4 (t, 3J = 3.4 Hz), 124.6 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 122.1, 119.7 (t, 1J = 242.3 Hz), 52.1, 19.9, 19.4 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: –82.83 (s) |

| 11 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.93 (t, 1H, J = 1.6 Hz). 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.64 (ddd, 1H, J = 7.7, 1.6, 1.2 Hz), 7.53 (dt, 1H, J = 7.7, 1.2 Hz), 7.35 (t, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.18 (s, 1H), 5.38 (m, 1H), 5.12 (m, 1H), 3.56 (s, 3H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.15 (m, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 197.3, 166.7, 142.4, 141.9, 141.6, 139.2, 138.6, 137.5, 131.0, 129.9, 129.1, 128.6, 128.3, 126.8, 125.8, 113.5, 51.9, 21.7, 19.9, 19.6 | |

| 12 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.42 (m, 1H), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 5.29 (m, 1H), 5.03 (m, 1H), 3.54 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.23 (s, 3H), 2.06 (m, 3H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 168.6, 142.7, 141.2, 139.7, 138.8, 137.8 (t, 2J = 27.6 Hz), 132.5 (t, 2J = 27.3 Hz), 130.7, 128.7 (t, 3J = 3.4 Hz), 128.6 (t, 3J = 7.6 Hz), 128.0, 126.8 (t, 4J = 1.9 Hz), 125.0 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 122.9 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 120.6 (t, 1J = 241.6 Hz), 113.2, 52.0, 21.7, 19.9, 19.3 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: – 82.49 (s) |

| 13 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.67 (t, 1H, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.54 (dt, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz), 7.42 (dt, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz), 7.36 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.20 (s, 1H), 3.70 (d, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.51 (s, 3H), 2.97 (sext., 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 1.71 (br. s, 1H), 1.26 (d, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 197.3, 167.0, 144.4, 141.9, 139.0, 138.7, 137.8, 132.2, 130.9, 129.2, 128.7, 127.8 (2C), 127.1, 68.4, 51.9, 42.3, 19.9, 19.6, 17.5197.3, 167.0, 144.4, 141.9, 139.0, 138.7, 137.8, 132.2, 130.9, 129.2, 128.7, 127.8 (2C), 127.1, 68.4, 51.9, 42.3, 19.9, 19.6, 17.5 | |

| 14 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.43 (s, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.25 (s, 1H), 7.23 (s, 2H), 7.16–7.21 (m, 1H), 3.53 (d, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.46 (s, 3H), 2.83 (sext., 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.24 (s, 3H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.14 (br. s, 1H), 1.14 (d, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 168.7, 143.9, 139.7, 138.8, 137.7 (t, 2J = 27.4 Hz), 132.4 (t, 2J = 27.3 Hz), 130.6, 128.8 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz), 128.7 (t, 3J = 3.5 Hz), 128.3 (t, 3J = 7.7 Hz), 128.2, 125.1 (t, 3J = 5.1 Hz), 124.1 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 120.4 (t, 1J = 241.3 Hz), 68.3, 52.0, 42.2, 19.8, 19.3, 17.3 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: – 82.21 (s) |

| 15 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.74 (m, 1H), 7.28 (m, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.19 (m, 2H), 4.43 (s, 2 H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 1.82 (s, 1H) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 139.5 (t, 4J = 1.5 Hz),139.5 (t, 2J = 28.8 Hz),136.2 (t, 3J = 2.1 Hz), 135.8, 133.3 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz), 130.9, 130.4 (t, 2J = 26.2 Hz), 130.0, 129.1 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 127.8 (t, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 124.7 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 122.5, 120.8 (t, 1J = 241.8 Hz), 62.0 (t,4J = 3.4 Hz), 19.5 (2C) | CDCl3, 282 MHz: -83.28 (s) |

| 16 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.45 (m, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.25 (m, 1H), 7.21 (s, 2H), 5.29 (s, 1H), 5.05 (t, 1H, J = 1.4 Hz), 4.48 (s, 2H), 2.23 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.06 (dd, 3H, J = 1.4, 0.8 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 142.5, 141.6, 139.3, 137.4 (t, 2J = 28.0 Hz), 136.3 (t, 4J = 2.1 Hz), 135.7, 131.3 (t,2J = 26.5 Hz), 131.1, 128.3, 128.0 (t, 3J = 7.8 Hz), 127.3 (t, 3J = 1.8 Hz), 125.1 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 122.9 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 121.7 (t, 1J = 241.5 Hz), 113.5, 62.2 (t, 4J = 3.2 Hz), 21.7, 19.5 (2C) | CDCl3, 282 MHz: – 82.87 (s) |

| 17 | (CDCl3, 500 MHz): 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.21 (m, 1H), 3.57 (s, 3H), 2.9 (sext., 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.31 (s, 3H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 1.23 (d, 6H, J = 6.9 Hz) | (CDCl3, 125 MHz):168.7, 148.8, 139.6, 138.7, 137.7 (t, 2J = 27.3 Hz), 132.6 (t, 2J = 27.3 Hz), 130.7, 128.8 (t, 3J = 3.4 Hz), 128.6 (t, 3J = 7.6 Hz), 128.0, 127.8 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz), 123.9 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 123.6 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 120.7 (t, 1J = 241.2 Hz), 52.0, 34.1, 23.9 (2C), 19.9, 19.4 | (CDCl3, 470 MHz): – 81.94 (s) |

| 18 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.25 (s, 1H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.14 (s, 1H), 7.12 (m, 1H), 7.05 (m, 1H), 4.39 (s, 2 H), 2.76 (sext., 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.41 (br. s, 1H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 1.1 (d, 6H, J = 6.9 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 149.1138.9, 137.3 (t, 2J = 27.8 Hz), 136.4, 135.2, 131.1 (t, 2J = 26.5 Hz), 130.5, 128.3, 128.0 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz), 127.7 (t, 3J = 7.8 Hz), 123.9 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 123.6 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz),121.7 (t, 1J = 240.8 Hz), 61.6 (t, 4J = 3.2 Hz), 33.9, 23.7 (2C), 19.3 (2C) | CDCl3, 282 MHz: − 82.66 (s) |

Table 6.

The physicochemical properties of synthesized bisarylic derivatives A1 to A5

| Compound | IUPAC Name |

Aspect | Mass of the starting material (mg) | Mass of the product | Rf value (PE:EtOAc) | m.p. (oC) | % yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 2-(3-(2-benzoyl-4,5-dimethylbenzoyl)phenyl)propanoic acid | White solid | 270 | 225 | 0.17 (5:5) | 86–88 | 80 |

| A2 | 2-(3-(difluoro(2-(methoxycarbonyl)-4,5-dimethylphenyl)methyl)phenyl)propanoic acid | White solid | 74 | 60 | 0.40 (9.5:0.5) | 98–100 | 78 |

| A3 | 2-((3-bromophenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoic acid | White solid | 100 | 83 | 0.28 (6:4) | 64–66 | 80 |

| A4 | 2-((3-acetylphenyl)difluoromethyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoic acid | White solid | 103 | 80 | 0.38 (8:2) | 118–120 | 74 |

| A5 | 2-(difluoro(3-isopropylphenyl)methyl)-4,5-dimethylbenzoic acid | White solid | 100 | 55 | 0.26 (7:3) | 152–154 | 53 |

Table 7.

Spectral data of synthesized bisarylic derivatives A1 to A5

| Compound | 1H NMR | 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) | 19F NMR (CDCl3, 282 MHz) | HRMS (ESI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.78 (m, 2H), 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.36 (t, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.17 (s, 1H), 3.77 (quad, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.51 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.33 (s, 3H), 1.51 (d, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 197.0, 179.7, 166.7, 141.9, 140.2, 138.9, 138.7, 137.9, 132.0, 131.0, 129.2, 128.7, 128.6, 128.1, 126.8, 51.9, 45.1, 19.9, 19.6, 18.0 | calcd. For C20H20O5Na: m/z [M + Na]+ 363.12029; found: 363.1203 (0 ppm); C20H19O5Na2: m/z [M-H + 2Na]+ 385.10224; found: 385.1014 (2 ppm). | |

| A2 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.44–7.46 (m, 3H), 7.33–7.40 (m, 3H), 3.76 (quad, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.56 (s, 3H), 2.33 (s, 3H), 2.32 (s, 3H), 1.50 (d, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 179.6, 168.5, 139.8, 139.7, 138.9, 138.3 (t, 2J = 27.7 Hz), 132.3 (t, 2J = 27.1 Hz), 130.8, 128.9 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz), 128.7 (t, 3J = 3.4 Hz), 128.5 (2C), 125.2 (t, 3J = 5.1 Hz), 120.4 (t, 1J = 241.6 Hz), 68.3, 52.0, 45.2, 19.9, 19.4, 18.1 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: – 82.30 (s) | calcd. For C20H20F2O4Na: m/z [M + Na]+ 385.12219; found: 385.1223 (0 ppm); C20H19O4F2Na2: m/z [M + Na]+ 407.10413; found: 407.1045 (0 ppm). |

| A3 | deuterated acetone, 300 MHz: 7.29–7.63 (m, 6H), 2.22 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 3H) | deuterated acetone, 75 MHz: 170.0, 142.4 (t, 2J = 28.6 Hz), 141.7, 141.1 (t, 4J = 1.3 Hz), 134.6 (t, 3J = 1.7 Hz), 133.7 (t, 2J = 26.9 Hz), 132.7, 132.1, 131.3, 130.7 (t, 3J = 5.3 Hz), 130.0 (t, 3J = 8.0 Hz), 126.8 (t,3J = 5.3 Hz), 123.4, 122.0 (t, 1J = 241.6 Hz), 20.8, 20.4 |

CDCl3, 282 MHz: − 82.34 (s) |

calcd. For C16H13O2F792BrNa: m/z [M + Na]+ 376.99592; found: 376.9958 (0 ppm); C16H12O2F792BrNa2: m/z [M-H + 2Na]+ 398.97786; found: 398.9779 (0 ppm); C16H12O2F79BrNa: m/z [M-HF + Na]+ 356.98969; found: 356.9905 (2 ppm) |

| A4 | deuterated acetone, 300 MHz: 8.18 (m, 1H), 8.07 (m, 1H), 7.77 (m, 1H), 7.56–7.61 (m, 3H), 2.60 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H) | deuterated acetone, 75 MHz: 198.5, 170.0, 141.7, 141.1, 140.6 (t, 2J = 28.5 Hz), 138.9, 133.9 (t, 2J = 27.1 Hz), 132.6, 132.1 (t,3J = 7.5 Hz), 131.4, 131.1 (t, 4J = 3.4 Hz), 130.4, 130.0 (t, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 127.2 (t, 3J = 5.3 Hz), 122.5 (t, 1J = 241.7 Hz), 27.7, 20.8, 20.3 |

CDCl3, 282 MHz: – 82.87 (s) |

calcd. For C18H16O3F2Na: m/z [M + Na]+ 341.09597; found: 341.0960 (0 ppm) |

| A5 | CDCl3, 300 MHz: 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.43 (s, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.15–7.17 (m, 3H), 2.81 (sext., 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.27 (s, 3H), 2.24 (s, 3H), 1.14 (d, 6H, J = 6.9 Hz) | CDCl3, 75 MHz: 172.7, 148.7, 140.5, 138.6, 137.6 (t, 2J = 27.2 Hz), 133.6 (t, 2J = 27.7 Hz), 131.4, 128.8 (t, 3J = 7.8 Hz), 127.9 (2C), 127.7 (t, 4J = 1.6 Hz), 124.1 (t, 3J = 5.0 Hz), 123.6 (t, 3J = 5.2 Hz), 120.6 (t, 1J = 241.7 Hz), 34.1, 23.8 (2C), 19.9, 19.4 | CDCl3, 282 MHz: –81.93 (s) | calcd. For C19H20O2F2Na: m/z [M + Na]+ 341.13236; found: 341.1321 (1 ppm); C19H19O2FNa: m/z [M-HF + Na]+ 321.12613; found: 321.1260 (0 ppm); C19H19O2F2Na2: m/z [M-H + 2Na]+ 363.1143; found: 363.1157 (4 ppm); C19H20O2F2K: m/z [M + K]+ 357.10629; found: 357.1059 (1 ppm); C19H19O2: m/z [M-HF-F]+ 279.13796; found: 279.1379 (0 ppm) |

Synthesis of gem-difluorobisarylic derivatives A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5

To alcohol in acetone was added dropwise under magnetic stirring at room temperature, a concentrated (5.4 M) solution of Jones reagent until disappearance of the starting material (TLC analysis). After addition of isopropanol (5 equiv.), the reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuum. After purification by chromatography on silica gel, carboxylic acid was obtained.

Supporting information

Experimental details and characterization data of new compounds with copies of 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra are presented in the supplementary section, Additional file 1.

Evaluation of inflammation in macrophages

C57BL/6J male mice (20–25 g, 8 week-old) were obtained from Charles River (Ecully, France) and the animal facility of the American University of Beirut. Mice were housed 5 per cage in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms, kept on a 12-h light–dark cycle, and provided with standard food and water ad lib and with enrichment environment (cotton cocoon) in the animal facility of the American University of Beirut. Body weight and food intake were monitored three times a week throughout the study period. ARRIVE guidelines were followed (Additional file 2). Approval for use of animals was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the American University of Beirut (IACUC # 16-09-m379).

On the day of the procedure, 2–3 mice were euthanatized after 3 min exposure to carbon dioxide. BMDM were isolated as previously described and were plated at 0.8 million cells per well [16]. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using F4/80 -APC antibody (BioLegend 123115) and showed 90% macrophages. BMDM were then treated for 24 h with different concentrations of the bisarylic derivative compounds for 30 min prior to the addition of 10 ng/mL LPS. DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.4% with no effect. The supernatants were assessed for IL-6, PGE2 and nitrite, the stable derivative of NO. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer containing inhibitors of protease. Total protein concentration was determined using DC protein assay (Bio-Rad 500-0115) with BSA as standard. IL-6, nitrite and PGE2 were measured as described previously [17]. Western blot of NOS-II and COX-2 was performed as previously described [17–19]. 10 µg of total protein was assessed. The primary antibodies were developed and characterized as previously described: for COX-2, mouse monoclonal antibody anti-COX-2 (clone COX-214, 1/5000) [20]; for NOS-II, rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-NOS-II (dilution1/2000) [21], and mouse β-actin (dilution 1/10,000) (Sigma-Aldrich A5441). Clarity™ western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad 170-5061) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to reveal positive bands visualized using Bio-Rad ChemiDoc.

COX-1 and COX-2 activities

For COX-1 activity, human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573, Manassas, VA USA) stably overexpressing human recombinant COX-1 were used [17]. Cells were treated with compounds A1 to A5 for 45 min in Hanks buffer and then 10 µM arachidonic acid (AA) were added for 30 min. PGE2 was measured and corresponded to the breakdown metabolism of PGH2 and PGE2.

For COX-2 activity, BMDM were treated with 10 μM acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for 30 min to irreversibly inhibit COX-1 and then washed and treated with LPS 10 ng/mL for 24 h. BMDM were treated with compounds A1 to A5 for 45 min in Hanks buffer, pH 7.4 containing 1 mg/mL BSA prior to the addition of 10 µM of AA for 30 min. Supernatants were collected and PGE2 was determined.

Toxicity assay

WST-1 assay was used to determine the toxicity of the synthesized compounds (Cell proliferation WST-1 assay, Sigma-Aldrich 5015944001). Briefly, macrophages (50,000 cells per well) were plated in a 96 well plate in RPMI culture medium containing 10% FBS and grown for 24 h. Cells (in triplicates) were treated at 25 and 50 μM of the tested compounds. Culture medium without cells and cells without treatment were used as control. Results were expressed as percentage of cells without treatment. All compounds showed 95% viability at 50 μM.

Molecular docking

Target and small molecule preparation

All small molecules (A1 to A5) were built using Openbabel chemical toolbox (PMID: 21982300) and subsequent low energy 3D conformations were generated using Frog2 (PMID: 20444874). Protonation state corresponded to a pH of 7. The 3D structure of the ovine COX-1 (PDBID: 1EQG) [13] and murine COX-2 (4ph9) [14] complexed with ibuprofen were selected for docking simulations using Autodock Vina (PMID: 19499576) optimized for virtual screening. The numbering of the amino acid residues in the PDB is different between ovine COX-1 and murine COX-2, i.e. Arg120 in COX-1 corresponds to Arg121 in murine COX-2. Water and other heteroatoms were removed from the structure. Chain A was retained including ibuprofen and heme group. Hydrogen atoms were added, atom typing, and partial charges were assigned using Amber forcefield in Chimera (PMID: 15264254). Corresponding ligand-receptor binding energies were estimated in kcal/mol and averaged for best poses that recapitulate ibuprofen binding. A single interacting conformation was retained after visual inspection in Maestro (Schrödinger, LLC).

Data analysis

IL-6, nitrite and PGE2 measurement were determined from 3 to 5 independent experiments and expressed as percentage of LPS alone and expressed as mean ± SEM. COX-1 activity for the compounds were expressed as percentage of PGE2 measured in cells exposed to vehicle and AA, and as percentage of PGE2 in cells treated with LPS, ASA and AA for COX-2. Curve fitting and calculation of the IC50 values were done using Grafit7 Software (Erithacus software, Staines, UK) and GraphPad Prism 6. Images of western blot were analyzed using ImageJ Software (version 1.52a, NIH, MA). Ratio of COX-2 to β-actin was determined and the results are expressed as fold of LPS signal.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05 (GraphPad Prism 6 Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Proton (H), carbon (C) and fluorine (F) NMR spectra for intermediates 4 to 18 and for compounds A1 to A5.

Acknowledgements

We thank the plate-forme of the Centre Régional de Mesures Physiques de l’Ouest (CRMPO) in Rennes, France for the mass spectral analysis. We thank all members the teams (Beirut and Rennes) for their kind help and stimulating discussions.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- ASA

acetylsalicylic acid

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS-II

nitric oxide synthase-II

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design (AH, AHachem and EH); design of the molecules and chemical synthesis (AHachem, LH, RG); acquisition of data (AA, LH, GEA); NH performed the molecular docking; analysis and interpretation of data (AA, LH, SG, GEA, OD, NB, BB, AHachem, EH, AH); IC50 analysis and fitting (OD and AA); drafting of the manuscript (AA, LH, GEA, AHachem, EH, AA); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AA, LH, GEA, RG, AHachem, EH, AH); statistical analysis (AA, AH); study supervision (AHachem, EH, AH). AHachem, EH and AH provided financial support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Grant Program at the Lebanese University, Lebanon (Ali Hachem and Eva Hamade) and the Medical Practice Plan and the University Research Board of the American University of Beirut (Aida Habib) (Grant No. 320024).

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abeer J. Ayoub, Layal Hariss and Nehme El-Hachem contributed equally to the work

Ali Hachem, Eva Hamade and Aida Habib are senior authors and contributed equally to this work

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13065-019-0640-5.

References

- 1.Özbey F, Taslimi P, Gülçin İ, Maraş A, Göksu S, Supuran CT. Synthesis of diaryl ethers with acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase inhibitory actions. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31(sup2):79–85. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1189422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung N, Bräse S. Synthesis of natural products on solid phases via copper-mediated coupling: synthesis of the aristogin family, spiraformin a, and hernandial. Eur J Org Chem. 2009;26:4494–4502. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200900632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ, Wiffen PJ. Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;9:CD008659. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008659.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanum SA, Begum BA, Girish V, Khanum NF. Synthesis and evaluation of benzophenone-N-ethyl morpholine ethers as anti-inflammatory agents. Int J Biomed Sci. 2010;6(1):60–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrazas PM, de Souza Marques E, Mariano LN, Cechinel-Filho V, Niero R, Andrade SF, Maistro EL. Benzophenone guttiferone A from Garcinia achachairu Rusby (Clusiaceae) presents genotoxic effects in different cells of mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e76485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deep A, Jain S, Sharma PC. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of some novel biphenyl-4-carboxylic acid 5-(arylidene)-2-(aryl)-4-oxothiazolidin-3-yl amides. Acta Pol Pharm. 2010;67(1):63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thuronyi BW, Chang MC. Synthetic biology approaches to fluorinated polyketides. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(3):584–592. doi: 10.1021/ar500415c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science (New York, NY) 2007;317(5846):1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaughnessy MJ, Harsanyi A, Li J, Bright T, Murphy CD, Sandford G. Targeted fluorination of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug to prolong metabolic half-life. ChemMedChem. 2014;9(4):733–736. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang H, Whittaker AM, Lalic G. Catalytic activation of a single C-F bond in trifluoromethyl arenes. Chem Sci. 2016;7(1):505–509. doi: 10.1039/C5SC03415A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillis EP, Eastman KJ, Hill MD, Donnelly DJ, Meanwell NA. Applications of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem. 2015;58(21):8315–8359. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalaf A, Grée D, Abdallah H, Jaber N, Hachem A, Grée R. A new flexible strategy for the synthesis of gem-difluoro-bisarylic derivatives and heterocyclic analogues. Tetrahedron. 2011;67(21):3881–3886. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selinsky BS, Gupta K, Sharkey CT, Loll PJ. Structural analysis of NSAID binding by prostaglandin H2 synthase: time-dependent and time-independent inhibitors elicit identical enzyme conformations. Biochemistry. 2001;40(17):5172–5180. doi: 10.1021/bi010045s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlando BJ, Lucido MJ, Malkowski MG. The structure of ibuprofen bound to cyclooxygenase-2. J Struct Biol. 2015;189(1):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hariss L, Ibrahim R, Jaber N, Roisnel T, Grée R, Hachem A. A general approach to various five- and six-membered gem-difluoroheterocycles: application to the synthesis of fluorinated analogues of sedamine. Eur J Org Chem. 2018;2018(27–28):3782–3791. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201800371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habib A, Chokr D, Wan J, Hegde P, Mabire M, Siebert M, Ribeiro-Parenti L, Le Gall M, Letteron P, Pilard N, et al. Inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase, an anti-inflammatory and antifibrogenic strategy in the liver. Gut. 2019;68:522–532. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Achkar GA, Jouni M, Mrad MF, Hirz T, El Hachem N, Khalaf A, Hammoud S, Fayyad-Kazan H, Eid AA, Badran B, et al. Thiazole derivatives as inhibitors of cyclooxygenases in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;750:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habib A, Shamseddeen I, Nasrallah MS, Antoun TA, Nemer G, Bertoglio J, Badreddine R, Badr KF. Modulation of COX-2 expression by statins in human monocytic cells. FASEB J. 2007;21(8):1665–1674. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6766com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mouawad CA, Mrad MF, Al-Hariri M, Soussi H, Hamade E, Alam J, Habib A. Role of nitric oxide and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein transcription factor in statin-dependent induction of heme oxygenase-1 in mouse macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creminon C, Frobert Y, Habib A, Maclouf J, Pradelles P, Grassi J. Immunological studies of human constitutive cyclooxygenase (COX-1) using enzyme immunometric assay. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1995;1254(3):333–340. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habib A, Bernard C, Lebret M, Creminon C, Esposito B, Tedgui A, Maclouf J. Regulation of the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 by nitric oxide in rat peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;158(8):3845–3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Proton (H), carbon (C) and fluorine (F) NMR spectra for intermediates 4 to 18 and for compounds A1 to A5.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.