Abstract

Objectives

We sought to evaluate the accuracy of standardized total plaque volume (TPV) measurement and low-density non-calcified plaque (LDNCP) assessment from coronary CT angiography (CTA) in comparison with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS).

Methods

We analyzed 118 plaques without extensive calcifications from 77 consecutive patients who underwent CTA prior to IVUS. CTA TPV was measured with semi-automated software comparing both scan-specific (automatically derived from scan) and fixed attenuation thresholds. From CTA, %LDNCP was calculated voxels below multiple LDNCP thresholds (30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 Hounsfield units [HU]) within the plaque. On IVUS, the lipid-rich component was identified by echo attenuation, and its size was measured using attenuation score (summed score analysis length) based on attenuation arc (1 = < 90°; 2 = 90–180°; 3 = 180–270°; 4 = 270–360°) every 1 mm.

Results

TPV was highly correlated between CTA using scan-specific thresholds and IVUS (r = 0.943, p < 0.001), with no significant difference (2.6 mm3, p = 0.270). These relationships persisted for calcification patterns (maximal IVUS calcium arc of 0°, < 90°, or ≥ 90°). The fixed thresholds underestimated TPV (− 22.0 mm3, p < 0.001) and had an inferior correlation with IVUS (p < 0.001) compared with scan-specific thresholds. A 45-HU cutoff yielded the best diagnostic performance for identification of lipid-rich component, with an area under the curve of 0.878 vs. 0.840 for < 30 HU (p = 0.023), and corresponding %LDNCP resulted in the strongest correlation with the lipid-rich component size (r = 0.691, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Standardized noninvasive plaque quantification from CTA using scan-specific thresholds correlates highly with IVUS. Use of a < 45-HU threshold for LDNCP quantification improves lipid-rich plaque assessment from CTA.

Keywords: Atherosclerotic plaque, Computed tomography angiography, Interventional ultrasonography

Introduction

The lipid-rich component is considered one of the major histopathologic features of high-risk coronary plaques prone to rupture [1–3]. Noninvasive imaging has, therefore, focused on identifying the lipid-rich component. On coronary CT angiography (CTA), the lipid-rich component is identified as low-density non-calcified plaque (LDNCP) [2, 4–7]. Landmark CTA studies have shown that the presence of LDNCP defined as < 30 HU is more frequent in patients with acute coronary syndrome than in patients in stable coronary artery disease [8] and is associated with subsequent coronary artery disease events [9].

Binary detection of LDNCP on two-dimensional cross sections used in most CTA studies [4, 6–9] can be affected by the location and/or size of regions of interest and contrast enhancement [10, 11], which have been shown to be inconsistent in prior reports [4, 5, 7]. In addition, a two-dimensional analysis based on mean HU hampers an assessment of the extent of the lipid-rich component. Volumetric analyses based on histogram analysis providing the volume or burden of LDNCP, which is independent of regions of interest, have additional clinical value [12–14]. Thus far, no in vivo study has investigated volumetric LDNCP measurement with varying HU thresholds on CTA compared with IVUS.

The aim of this study was to examine the accuracy of semi-automated TPV quantification and lipid-rich plaque assessment using attenuation histogram-based LDNCP analysis, in a head-to-head comparison with IVUS.

Materials and methods

All imaging studies were clinically indicated. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients for the use of their data for research.

Patients

This retrospective study included 77 consecutive patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease who underwent CTA before IVUS within a period of 1 month at Kusatsu Heart Center. Exclusion criteria are composed of poor image quality on CTA or IVUS, patients with acute myocardial infarction, stented lesions, predilatation before IVUS examination, or presence of extensive acoustic shadowing from calcification (arc of ≥ 90° and ≥ 3 mm in length) on IVUS, which precludes accurate measurement of vessel and plaque by IVUS (Supplement).

Image acquisition

IVUS

All IVUS examinations were performed prior to percutaneous coronary intervention in a standard fashion with commercially available 40-MHz imaging catheters (Boston Scientific or Terumo) as described previously [15]. The imaging catheter was advanced beyond the distal portion of the target lesion for percutaneous coronary intervention, and automated pullback was performed at a rate of 0.5 mm/s.

CTA

CTA images were acquired with a 64-detector scanner (Lightspeed VCT, GE Healthcare) utilizing prospective ECG-gating or retrospective ECG-gating with tube current modulation. All patients received nitroglycerin for coronary vasodilation, and those with a heart rate over 60 beats per minute were given beta-blockers unless a contraindication was present. An intravenous bolus of iopamidol (Iopamiron 370, Schering) was continuously injected for 10–12 s, depending on the scan length, followed by a 20:80 admixture of contrast agent (25 ml). The injection rate of contrast agent was adjusted according to body weight (2.7–5.6 ml/s) [16]. Real-time bolus-tracking technique was used to trigger scan initiation. The scan parameters were collimation of 64 × 0.625 mm, rotation time of 350 ms, tube voltage of 100 or 120 kV, and tube current of 450–780 mAs. Transaxial images were reconstructed with filtered backprojection reconstruction algorithm at the cardiac phase exhibiting minimal cardiac motion. Image reconstruction parameters comprised the individually adapted field of view, matrix size of 512 × 512 pixels, and a medium-soft tissue convolution kernel.

Data analysis

IVUS

IVUS analysis was performed as reported previously [15] using dedicated software (echoPlaque, INDEC Medical Systems) by experienced observers, who were blinded regarding the result of CTA. We identified intracoronary atherosclerotic lesions on IVUS with maximal plaque thickness of > 1.0 mm and plaque burden (vessel area plaque area) of ≥ 40% [17, 18]. The proximal and distal reference segments were selected at the most adjacent points to the maximal stenosis in which there was minimal or no plaque. Vessel (external elastic membrane) and lumen contours were manually delineated every 1 mm, and TPV was calculated as the vessel volume minus the lumen volume.

Calcium was defined by the presence of a bright echogenic signal with acoustic shadowing. The arc of acoustic shadowing was measured in degrees with a protractor centered on the lumen every 1 mm, and the maximal arc of calcium deposit was identified. Spotty and large calcifications were defined as calcium deposits with an arc of < 90° and ≥ 90°, respectively [19, 20]. The lipid-rich component was identified by superficial echo attenuation (leading edge of attenuation closer to the lumen than to the adventitia) despite the absence of bright calcium [21–23]. The arcs of attenuation were measured in degrees with a protractor centered on the lumen every 1 mm and were graded based on a 5-point scale (0, no attenuation; 1, 0–90°; 2, 90–180°; 3, 180–270°; 4, 270–360°) to create the mean attenuation score (summed score analysis length) [24].

CTA

Quantitative analysis of CTA images was performed with dedicated software (Autoplaque version 2.0, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center) by an independent observer blinded to IVUS findings as previously described (details in Supplement) [11, 25, 26]. Excellent intra-observer reproducibility and inter-observer reproducibility have been previously reported [25, 27]. Plaque co-registration between CTA and IVUS was performed by another investigator, who was not involved in the other processing of CTA analysis. Stretched multiplanar reconstruction and cross-sectional CTA images were used to compare IVUS images. The proximal and distal reference limits of the plaque were matched to IVUS using anatomical landmarks, such as the distance from the aorto-coronary ostium, target lesions, side branches, or calcifications. Plaque volumes for total and each component were automatically quantified using scan-specific thresholds. The plaque composition was derived as (plaque component volume TPV) × 100 (%). For quantitative LDNCP analysis, the percentages of voxels below multiple LDNCP thresholds (30, 45, 60, 75, or 90 HU) within the plaque were calculated from CTA. CT attenuation of voxels located < 0.5 mm inward from the vessel boundaries was considered to be within the LDNCP threshold due to partial volume effects between the plaque and epicardial fat tissue; these voxels were excluded from the measurement of LDNCP in this study using standardized “erosion” from the vessel centerline. When there was a difference in lesion length between two modalities (possibly due to catheter-induced deformation of the coronary artery, cardiac motion, or pullback speed variations), volume parameters in CTA were corrected by the lesion length (volume parameters in CTA × the lesion length in IVUS the lesion length in CTA) [28]. An example of semi-automated TPV quantification from CTA is shown in Fig. 1. TPV was also quantified using previously reported fixed HU thresholds (non-calcified plaque, < 150 HU; lumen, 150–500 HU; calcified plaque, > 500 HU) [29, 30].

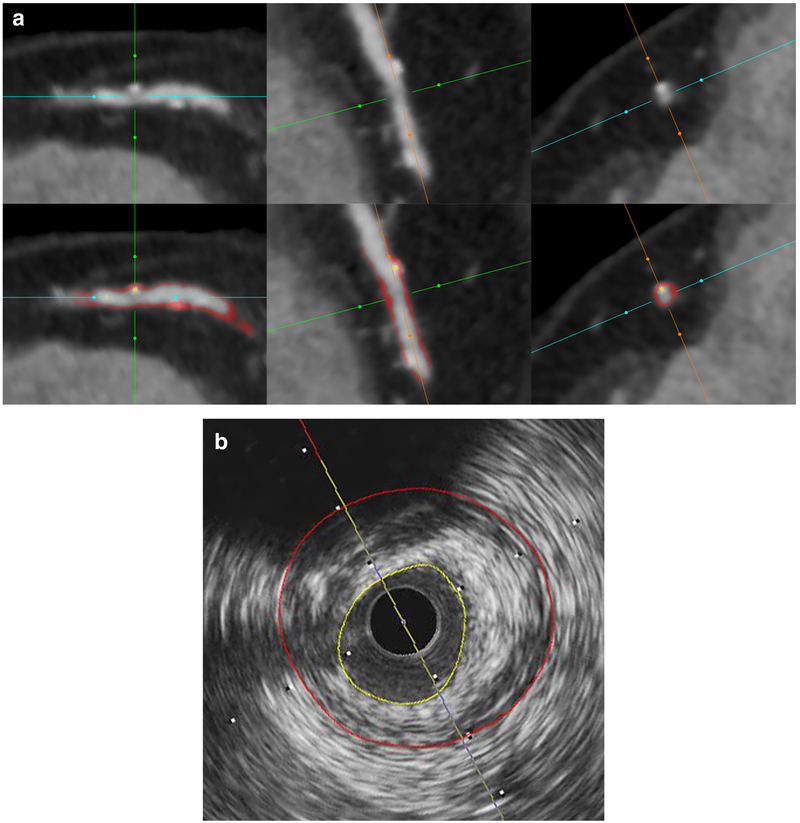

Fig. 1.

An example of semi-automated quantification from CTA. a Cross-sectional and double oblique CTA images of multiplanar reconstruction showing non-calcified plaque with spotty calcification without (top) or with (bottom) color-coded overlay from automated plaque quantification. Yellow overlay corresponds to calcified plaque and red to non-calcified plaque. b Corresponding IVUS cross section with external elastic membrane (red) and lumen (yellow) contours. CTA, coronary CT angiography; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corporation). Quantitative variables were expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies or percentages. Intra-observer agreement and inter-observer agreement for calcification and echo attenuation on IVUS assessment were examined using Cohen’s kappa coefficient and Bland-Altman analysis. Correlations between two variables were assessed with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare TPV between IVUS and CTA. The agreement of TPV between IVUS and CTA was examined using Bland-Altman analysis. Two dependent correlations being equal using Fisher’s z-transformation was used to compare CTA TPV between the scan-specific and fixed thresholds. The receiver operating characteristic analysis was applied to determine the diagnostic performance for identification of IVUS-verified lipid-rich component at each LDNCP threshold [31]. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and IVUS findings

A total of 118 atherosclerotic plaques from 77 patients were examined. CTA was performed at 100 kV in 32 patients (42%) and at 120 kV in 45 (58%). Clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. On IVUS, 54 (46%) and 41 (35%) plaques were accompanied by spotty and large calcifications, respectively. The remaining 23 (19%) plaques were unaccompanied by any calcification. The lipid-rich component was observed in 63 (53%) plaques.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and plaque morphology

| No. of patients | 77 |

| Age (years) | 68 (60–76) |

| Male, n (%) | 61 (79) |

| Weight (kg) | 61.1 (52.5–70.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.5 (21.3–24.9) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Stable angina/unstable angina, n (%) | 62 (81)/15 (19) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 61 (79) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 33 (43) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 38 (49) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 12 (16) |

| Target vessel (LAD/LCX/RCA), n (%) | 50 (65)/5 (7)/22 (29) |

| No. of plaques | 118 |

| Plaque morphology on IVUS | |

| Pattern of calcification | |

| No calcification, n (%) | 23 (19) |

| Spotty calcification, n (%) | 54 (46) |

| Large calcification, n (%) | 41 (35) |

| Superficial echo attenuation, n (%) | 63 (53) |

Values are expressed as median (interquartile range) or n (%)

IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex coronary artery; LM, left main; RCA, right coronary artery

Reproducibility of IVUS plaque measurements

Intra-observer and inter-observer reproducibility for calcification patterns, presence of echo attenuation, and the mean attenuation score on IVUS assessment were evaluated in randomly selected 20 patients (36 plaques). Intra-observer agreement and inter-observer agreement for calcification patterns (no, spotty, or large calcification) were κ values of 0.91 and 0.87 (p < 0.001 for both), respectively. The mean differences in the maximal calcium arc (with the 95% limits of agreement) were − 0.1° (− 11.1 to 10.8°) and − 0.8° (− 13.4 to 11.8°) for intra-observer and inter-observer measurement, respectively. For presence of echo attenuation, intra-observer agreement and inter-observer agreement were κ values of 0.94 and 1.0 (p < 0.001 for both), respectively. The mean differences in the mean attenuation score (with the 95% limits of agreement) were − 0.009 (− 0.280 to 0.261) and − 0.012 (− 0.289 to 0.265) for intra-observer and inter-observer measurement, respectively.

Comparison of TPV

CTA and IVUS

Due to extensive echo attenuation on IVUS precluding measurement, 4 plaques from 4 patients were excluded from the TPV analysis. In all the other plaques, the median scan-specific attenuation thresholds were – 19 HU (IQR – 30 to − 9) for epicardial fat, 193 HU (IQR 165 to 213) for the upper level of non-calcified plaque, and 505 HU (IQR 460 to 550) for the lower level of calcified plaque, respectively.

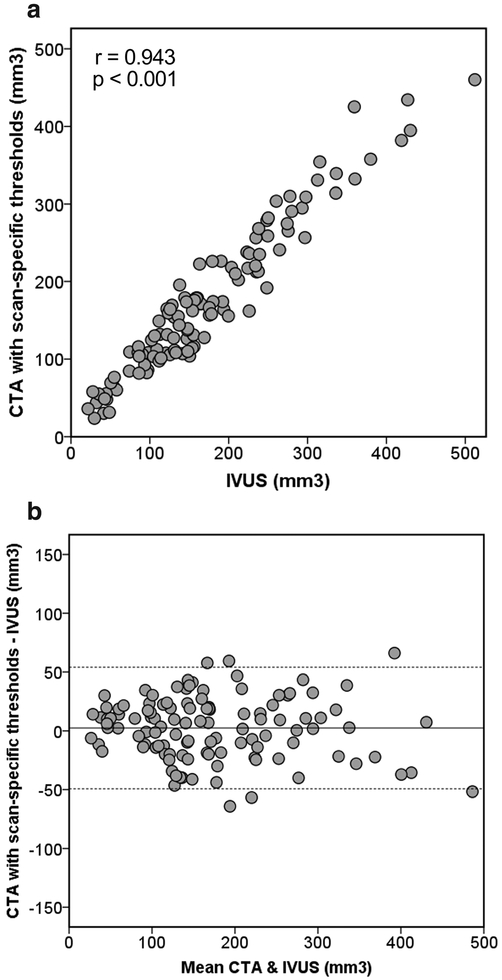

Figure 2a displays a scatter plot of CTA TPV quantified with scan-specific thresholds and IVUS TPV. TPV was highly correlated between CTA and IVUS (r = 0.943, p < 0.001). Table 2 summarizes comparisons of TPV between CTA and IVUS according to various lesion subsets. The relationships persisted for all calcification patterns and presence of lipid-rich component (p < 0.001 for all). By Bland-Altman analysis, the mean difference was 2.6 mm3, and the 95% limits of agreement were − 49.3 to 54.4 mm3 (Fig. 2b). TPV was not significantly different between CTA and IVUS (158.9 mm3 [IQR 106.8–228.3] vs. 152.1 mm3 [IQR 104.0–234.7], p = 0.270). The differences were not significant irrespective of calcification patterns (p = 0.784, p = 0.542, and p = 0.232 for no, spotty, and large calcification, respectively) and presence of lipid-rich component (p = 0.566 and p = 0.307 for presence and absence of lipid-rich component, respectively). When CTA TPV was not corrected (166.6 mm3 [IQR 106.4–234.8]) by the lesion length (CTA, 19.9 mm [IQR 13.9–24.3] vs. IVUS, 19.2 mm [IQR 13.3–23.5], p < 0.001), the mean difference from IVUS TPV was 6.7 mm3 (p = 0.006), and the 95% limits of agreement were − 43.9 to 57.3 mm3. The correlation with IVUS TPV persisted (r = 0.944, p < 0.001) without the correction.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of total plaque volume between CTA with scan specified thresholds and IVUS. a Scatterplot. b Bland-Altman plot. The solid line is the mean bias (2.6 mm3), and the dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement (− 49.3 to 54.4 mm3). CTA, coronary CT angiography; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

Table 2.

Comparison of total plaque volume between CTA with scan-specific thresholds and IVUS according to lesion subtypes

| n | CTA median | IVUS median | p value | Mean bias | Limits of | Correlation | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (IQR) (mm3) | (IQR) (mm3) | (CTA-IVUS) (mm3) | agreement (mm) | coefficient | ||||

| All | 114 | 158.8 (106.8–228.3) | 152.1 (104.0–234.7) | 0.270 | 2.6 | −49.3 to 54.4 | 0.943 | < 0.001 |

| Pattern of calcification | ||||||||

| No calcification | 23 | 131.9 (84.5–218.1) | 130.9 (74.0–203.6) | 0.784 | −1.1 | −37.9 to 35.6 | 0.965 | < 0.001 |

| Spotty calcification | 51 | 137.6 (108.4–212.9) | 147.4 (96.2–226.0) | 0.542 | 1.5 | −50.6 to 53.6 | 0.927 | < 0.001 |

| Large calcification | 40 | 169.9 (114.2–300.5) | 159.8 (126.8–279.4) | 0.232 | 6.1 | −52.7 to 64.8 | 0.945 | < 0.001 |

| Lipid-rich component | ||||||||

| + | 59 | 202.1 (139.4–258.8) | 199.6 (136.0–250.1) | 0.566 | 2.1 | −53.5 to 57.8 | 0.941 | < 0.001 |

| − | 55 | 114.1 (82.4–166.2) | 122.0 (74.0–155.3) | 0.307 | 3.0 | −44.8 to 50.9 | 0.901 | < 0.001 |

CTA, coronary CT angiography; IQR, interquartile range; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

Scan-specific thresholds vs. fixed thresholds

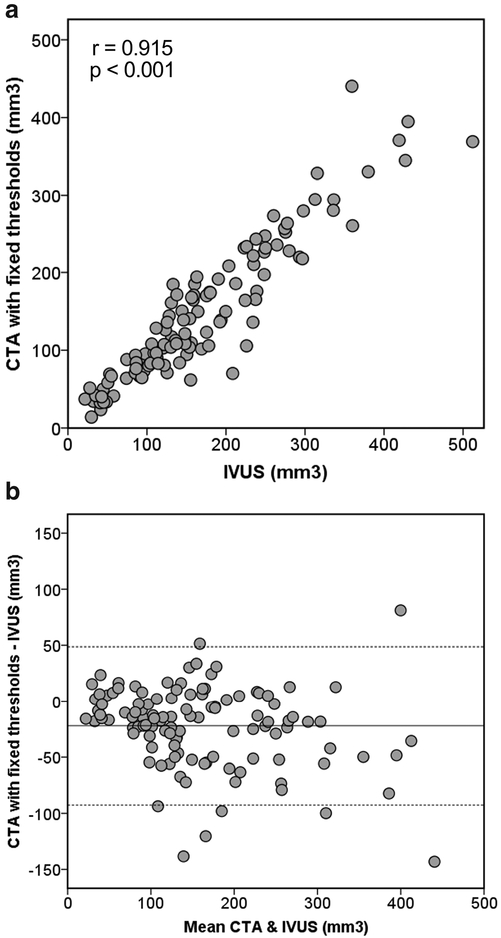

CTA TPV quantified with the fixed thresholds also correlated well with IVUS TPV (r = 0.915, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3a); CTA with the fixed thresholds significantly underestimated TPV (127.3 mm3 [IQR 83.1–208.8] vs. 152.1 mm3 [IQR 104.0–234.7], p < 0.001). Compared with scan-specific thresholds, the fixed thresholds had a greater bias with wider limits of agreement (− 22.0 mm3 with − 92.7 to 48.7 mm3) (Fig. 3b) and an inferior correlation with IVUS (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of total plaque volume between CTA with fixed thresholds and IVUS. a Scatterplot. b Bland-Altman plot. The solid line is the mean bias (− 22.0 mm3), and the dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement (− 92.7 to 48.7 mm3). CTA, coronary CT angiography; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

Assessment of lipid-rich component by volumetric LDNCP measurement

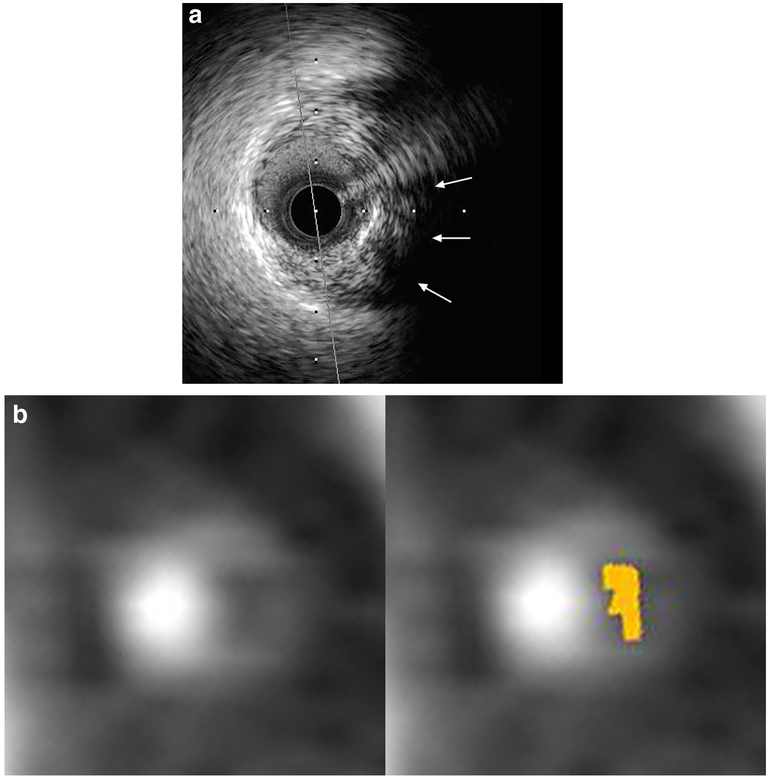

Table 3 summarizes plaque compositions from CTA quantified using scan-specific thresholds for plaques with and without lipid-rich component. The percentages of non-calcified and calcified plaque were not significantly different between plaques with lipid-rich component and those without. Plaques with lipid-rich component had significantly greater percentages of LDNCP than those without lipid-rich component for all LDNCP thresholds (p < 0.001 for all). Figure 4 shows an example of LDNCP on CTA with the corresponding IVUS cross section with the lipid-rich component.

Table 3.

Comparison of plaque composition between plaques with and without lipid-rich component

| Plaque composition | Lipid + (n = 63) | Lipid - (n = 55) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcified plaque (%) | 3.17 (0.00–10.48) | 4.86 (0.40–14.54) | 0.149 |

| Non-calcified plaque (%) | 96.83 (89.52–100.00) | 95.14 (85.46–99.60) | 0.149 |

| LDNCP < 30HU(%) | 0.55 (0.12–1.54) | 0.00 (0.00–0.04) | < 0.001 |

| LDNCP < 45HU(%) | 1.44 (0.52–3.38) | 0.00 (0.00–0.19) | < 0.001 |

| LDNCP < 60HU(%) | 3.10 (1.37–8.18) | 0.18 (0.00–0.79) | < 0.001 |

| LDNCP < 75HU(%) | 5.86 (2.49–10.50) | 0.49 (0.00–1.73) | < 0.001 |

| LDNCP < 90HU(%) | 9.34 (4.13–14.52) | 1.05 (0.06–3.58) | < 0.001 |

Values are expressed as median (interquartile range)

LDNCP, low-density non-calcified plaque

Fig. 4.

An example of IVUS-verified lipid-rich component with corresponding cross-sectional CTA images. a IVUS cross section with superficial echo attenuation (arrows). b Corresponding CTA cross sections with (left) and without (right) color-coded overlay from low-density non-calcified plaque quantification. Light brown overlay indicates pixels with < 45 Hounsfield units. CTA, coronary CT angiography; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

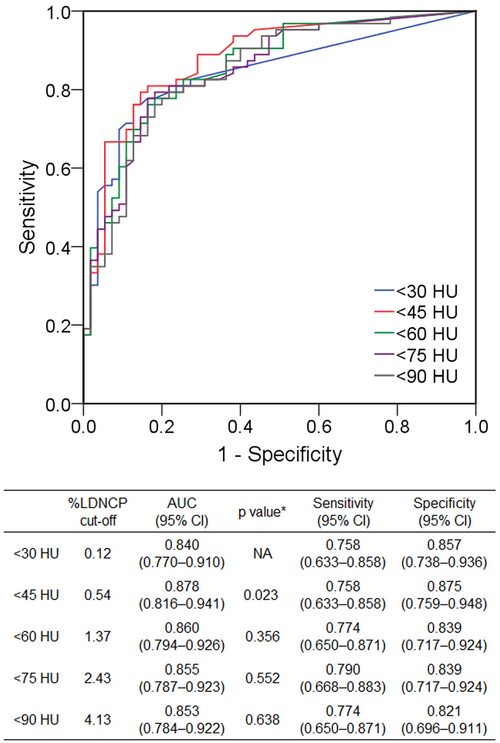

Figure 5 demonstrates the diagnostic performance of volumetric LDNCP measurement at varying thresholds for identification of lipid-rich component. On the receiver operating characteristic analysis, the best diagnostic performance was obtained by a 45-HU cutoff, with an area under the curve of 0.878 (95% confidence interval 0.816–0.941). Of the HU thresholds studied, the generally accepted 30-HU threshold resulted in the smallest area under the curve of 0.840 (95% confidence interval 0.784–0.922, p = 0.023 vs. 45 HU).

Fig. 5.

Diagnostic performance of volumetric LDNCP measurement at various HU cutoffs for identification of IVUS-verified lipid-rich component. *vs. < 30 HU. AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; HU, Hounsfield units; LDNCP, low-density non-calcified plaque; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; NA, not applicable

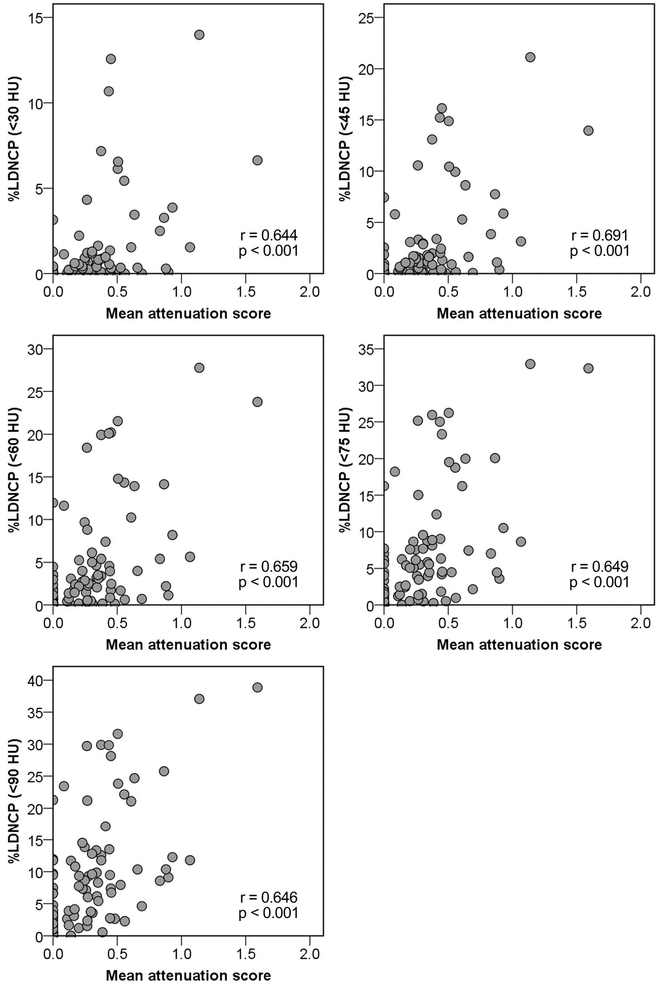

Figure 6 displays scatter plots of the lipid-rich component size, expressed as the mean attenuation score, and %LDNCP at various HU cutoffs. %LDNCP correlated with the lipid-rich component size at all HU thresholds, and the strongest correlation was observed at a 45-HU cutoff (r = 0.644, 0.691, 0.659, 0.649, and 0.646 for 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 HU, respectively, p < 0.001 for all).

Fig. 6.

Correlations of %LDNCP at various HU cutoffs with IVUS-verified lipid-rich component. HU, Hounsfield units; LDNCP, low-density non-calcified plaque; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound

Discussion

The major findings in the present study are summarized as follows: (1) Automated scan-specific threshold level-based TPV from CTA highly correlated with IVUS TPV irrespective of lesion subsets and (2) A < 45-HU threshold for volumetric LDNCP measurement provided the optimum assessment of lipid-rich component.

Measurement of TPV

Intravascular imaging has been widely used as a reference standard for plaque quantification as well as plaque characterization [15, 17, 21, 32]. However, it is invasive and its use is limited to specific lesions only. CTA is a more attractive alternative to intravascular imaging, allowing noninvasive plaque assessment in the whole coronary tree in a broad range of population. A recent serial CTA study has demonstrated that quantitative plaque assessment provides additional values in predicting future cardiac events over conventional assessment based on stenosis and/or qualitative plaque analysis [33].

Although the manual method is still standard for plaque quantification on CTA [34], it is time-consuming and dependent on visual inspection by observers. Several semi-automated techniques have been proposed to overcome the limitations. HU thresholds are commonly used to define plaque components and lumen [8, 11, 25, 26, 29, 30]. It has been demonstrated that plaque attenuation is dependent on luminal contrast opacification [10, 35, 36]. Luminal contrast enhancement varies widely among individuals and/or scans as a number of patient-related and CT scanning-related factors affect contrast enhancement [37]. Therefore, optimal HU thresholds for plaque should be scan-specific. CTATPV quantified with scan-specific attenuation thresholds has been shown to have a high correlation with IVUS TPV in non-calcified plaques [26]. In a prior study, the fixed HU threshold of 150 HU for the lower level of lumen (i.e., the upper level of non-calcified plaque) yielded a small difference in TPV (3.8 mm3) from IVUS TPV [30], whereas the fixed threshold significantly underestimated TPV in our patient group. The scan-specific threshold for the lower level of lumen used in the present study was higher (median 193 HU, IQR 165–213 HU) than the fixed threshold of 150 HU. These might explain, in part, our findings.

Interestingly, the lesion length by CTA was somewhat longer compared with that with IVUS despite registration of studied lesions between the two modalities using anatomical landmarks. This difference might be attributed to the inherent differences between invasive IVUS imaging within the vessel and x-ray transmission through the heart by noninvasive CTA. Since differences in lesion length directly affect volumetric measurements, the finding should be taken into account when comparing volumetric parameters between invasive and noninvasive modalities.

Three-dimensional histogram-based lipid-rich plaque characterization

CTA can non-invasively characterize coronary plaque based on differences in plaque attenuation [2, 4–7]. Even though mean HU-based criteria on a cross section are widely used [2, 4, 5, 7–9], there are several drawbacks. Various components often coexist in coronary atherosclerotic plaques [6, 21, 38], which can cause substantial overlaps in the distribution of mean HU value between lipid-rich and fibrous plaques [5, 7]. In addition, differences in methodology resulted in a wide variation in reported attenuation values for lipid-rich plaque [4–7].

To overcome the limitations of the HU-based criteria on a cross section, several reports have proposed histogram-based LDNCP analyses, which are independent of regions of interest. Ex vivo studies using two-dimensional quantitative histogram analysis reported AUCs of 0.65 and 0.74 for detection of lipid-rich plaque [6, 39]. The current study using three-dimensional histogram analysis yielded better diagnostic performance compared with the prior reports using two-dimensional analysis. Marwan et al. demonstrated that in non-calcified plaques, quantitative histogram analysis using a threshold of 30 HU identified lipid-rich plaques defined by IVUS with high sensitivity and specificity [5]. To our knowledge, this is the first to reveal the feasibility of three-dimensional quantitative LDNCP analysis in various plaque subtypes in vivo. Of the HU thresholds studied between 30 and 90 HU, the generally accepted 30-HU threshold had the lowest diagnostic performance in a real-world patient population, and a 45-HU threshold was found to be optimal for identification of lipid-rich component using volumetric LDNCP analysis in this study population.

Beyond binary detection of the lipid-rich component, estimation of its size is of clinical importance. On gray-scale IVUS, superficial echo attenuation is considered to be the most reliable signature for identifying a high-risk plaque corresponding to histologically verified lipid-rich necrotic core [21]. Its extent is associated with poor clinical outcomes [20, 24, 40, 41]. Since the standard HU-based characterization on a cross section precludes assessment of the lipid-rich component size, three-dimensional histogram-based LDNCP analysis could provide incremental prognostic information as well as more accurate and objective risk stratification of coronary plaque. In the present study, we demonstrated correlations between %LDNCP and the lipid-rich component size on IVUS, expressed as the mean attenuation score, for kV settings of 100 kV and 120 kV, which are used most often for CTA. In line with the best threshold for the identification of lipid-rich plaque component, a 45-HU threshold yielded the best correlation with the lipid-rich component size for our data, which may be of importance in future clinical research studies.

Clinical implications

The clinical importance of plaque quantification from CTA has been shown in several clinical studies. Our results confirm the accuracy of automated scan-specific threshold-based TPV measurement for various plaque subtypes from noninvasive CTA. Accurate assessment of LDNCP provided by the three-dimensional volumetric measurement with the < 45-HU threshold could enhance further risk stratification and enable evaluation of therapy in longitudinal studies.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study. Second, IVUS evaluations were limited to coronary arteries with significant stenosis, in which percutaneous coronary intervention was clinically indicated. We also included mild to moderate lesions in the same vessel, which were not targeted for revascularization, to compensate for this limitation. Third, CTA data were reconstructed with a filtered backprojection reconstruction method. Since newer technologies include varying levels/types of iterative reconstruction, CTA data reconstructed with filtered backprojection was chosen to ensure a consistent reconstruction and image noise level. Fourth, we excluded heavily calcified lesion which precludes accurate plaque assessment with IVUS and thus cannot be reasonably included in a head-to-head comparison with CT. Last, in a clinical setting where histological analysis is not feasible, cardiovascular events could be the gold standard for the true high-risk plaque. Further investigation is necessary whether volumetric LDNCP analysis improves prediction of cardiovascular events.

Conclusions

Standardized plaque quantification from noninvasive coronary CT angiography provides accurate total plaque volume measurement compared with IVUS. Attenuation histogram-based LDNCP quantification can improve lipid-rich plaque assessment from coronary CT angiography.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Standardized scan-specific threshold-based plaque quantification from coronary CT angiography provides an accurate total plaque volume measurement compared with intravascular ultrasound.

Attenuation histogram-based low-density non-calcified plaque quantification can improve lipid-rich plaque assessment from coronary CT angiography.

Funding

This work was funded by National Institute of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 1R01HL133616 (to Dr. Dey), and partially by a grant from the Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

- CTA

Coronary CT angiography

- HU

Hounsfield units

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IVUS

Intravascular ultrasound

- LDNCP

Low-density non-calcified plaque

- TPV

Total plaque volume

Footnotes

Guarantor The scientific guarantor of this publication is Damini Dey, PhD.

Conflict of interest Damini Dey, Sebastien Cadet, Piotr J Slomka, and Daniel S Berman received software royalties from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; Damini Dey, Piotr J Slomka, and Daniel S Berman have a patent.

Statistics and biometry One of the authors has significant statistical expertise.

Informed consent Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study.

Ethical approval Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

- retrospective

- diagnostic study

- performed at one institution

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06219-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A et al. (2001) The thin-cap fibroatheroma: a type of vulnerable plaque: the major precursor lesion to acute coronary syndromes. Curr Opin Cardiol 16:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurovich-Horvat P, Ferencik M, Voros S, Merkely B, Hoffmann U (2014) Comprehensive plaque assessment by coronary CT angiography. Nat Rev Cardiol 11:390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, Finn AV, Virmani R (2013) Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists’ view. Eur Heart J 34:719–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motoyama S, Kondo T, Anno H et al. (2007) Atherosclerotic plaque characterization by 0.5-mm-slice multislice computed tomographic imaging. Circ J 71:363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marwan M, Taher MA, El Meniawy K et al. (2011) In vivo CT detection of lipid-rich coronary artery atherosclerotic plaques using quantitative histogram analysis: a head to head comparison with IVUS. Atherosclerosis 215:110–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han D, Torii S, Yahagi K et al. (2018) Quantitative measurement of lipid rich plaque by coronary computed tomography angiography: a correlation of histology in sudden cardiac death. Atherosclerosis 275:426–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obaid DR, Calvert PA, Gopalan D et al. (2013) Atherosclerotic plaque composition and classification identified by coronary computed tomography: assessment of computed tomography-generated plaque maps compared with virtual histology intravascular ultra-sound and histology. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6:655–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motoyama S, Kondo T, Sarai M et al. (2007) Multislice computed tomographic characteristics of coronary lesions in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 50:319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motoyama S, Ito H, Sarai M et al. (2015) Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 66:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horiguchi J, Fujioka C, Kiguchi M et al. (2007) Soft and intermediate plaques in coronary arteries: how accurately can we measure CT attenuation using 64-MDCT? AJR Am J Roentgenol 189:981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dey D, Achenbach S, Schuhbaeck A et al. (2014) Comparison of quantitative atherosclerotic plaque burden from coronary CT angiography in patients with first acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 8:368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaur S, Ovrehus KA, Dey D et al. (2016) Coronary plaque quantification and fractional flow reserve by coronary computed tomography angiography identify ischaemia-causing lesions. Eur Heart J 37:1220–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hell MM, Motwani M, Otaki Y et al. (2017) Quantitative global plaque characteristics from coronary computed tomography angiography for the prediction of future cardiac mortality during long-term follow-up. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 18:1331–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang HJ, Lin FY, Lee SE et al. (2018) Coronary atherosclerotic precursors of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:2511–2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD et al. (2001) American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on cClinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 37:1478–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto H, Watanabe S, Kyo E et al. (2019) Effect of tube potential and luminal contrast attenuation on atherosclerotic plaque attenuation by coronary CT angiography: in vivo comparison with intravascular ultrasound. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, in press. 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ et al. (2011) A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 364:226–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Giessen AG, Toepker MH, Donelly PM et al. (2010) Reproducibility, accuracy, and predictors of accuracy for the detection of coronary atherosclerotic plaque composition by computed tomography: an ex vivo comparison to intravascular ultrasound. Invest Radiol 45:693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M et al. (2004) Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 110:3424–3429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiono Y, Kubo T, Tanaka A et al. (2013) Impact of attenuated plaque as detected by intravascular ultrasound on the occurrence of microvascular obstruction after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 6:847–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pu J, Mintz GS, Biro S et al. (2014) Insights into echo-attenuated plaques, echolucent plaques, and plaques with spotty calcification: novel findings from comparisons among intravascular ultrasound, near-infrared spectroscopy, and pathological histology in 2,294 human coronary artery segments. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:2220–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang SJ, Mintz GS, Pu J et al. (2015) Combined IVUS and NIRS detection of fibroatheromas: histopathological validation in human coronary arteries. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 8:184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pu J, Mintz GS, Brilakis ES et al. (2012) In vivo characterization of coronary plaques: novel findings from comparing greyscale and virtual histology intravascular ultrasound and near-infrared spectroscopy. Eur Heart J 33:372–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu X, Mintz GS, Xu K et al. (2011) The relationship between attenuated plaque identified by intravascular ultrasound and no-reflow after stenting in acute myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS - AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 4:495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dey D, Cheng VY, Slomka PJ et al. (2009) Automated 3-dimensional quantification of noncalcified and calcified coronary plaque from coronary CT angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 3:372–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dey D, Schepis T, Marwan M, Slomka PJ, Berman DS, Achenbach S (2010) Automated three-dimensional quantification of noncalcified coronary plaque from coronary CT angiography: comparison with intravascular US. Radiology 257:516–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng VY, Nakazato R, Dey D et al. (2009) Reproducibility of coronary artery plaque volume and composition quantification by 64-detector row coronary computed tomographic angiography: an intraobserver, interobserver, and interscan variability study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 3:312–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HB, Lee BK, Shin S et al. (2015) Clinical feasibility of 3D automated coronary atherosclerotic plaque quantification algorithm on coronary computed tomography angiography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Eur Radiol 25:3073–3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komatsu S, Hirayama A, Omori Y et al. (2005) Detection of coronary plaque by computed tomography with a novel plaque analysis system, ‘Plaque Map’, and comparison with intravascular ultra-sound and angioscopy. Circ J 69:72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uetani T, Amano T, Kunimura A et al. (2010) The association between plaque characterization by CT angiography and post-procedural myocardial infarction in patients with elective stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zweig MH, Campbell G (1993) Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 39:561–577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ et al. (2011) Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med 365:2078–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SE, Sung JM, Rizvi A et al. (2018) Quantification of coronary atherosclerosis in the assessment of coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 11:e007562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakazato R, Shalev A, Doh JH et al. (2013) Aggregate plaque volume by coronary computed tomography angiography is superior and incremental to luminal narrowing for diagnosis of ischemic lesions of intermediate stenosis severity. J Am Coll Cardiol 62:460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cademartiri F, Mollet NR, Runza G et al. (2005) Influence of intracoronary attenuation on coronary plaque measurements using multislice computed tomography: observations in an ex vivo model of coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur Radiol 15:1426–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalager MG, Bottcher M, Andersen G et al. (2011) Impact of luminal density on plaque classification by CT coronary angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 27:593–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bae KT (2010) Intravenous contrast medium administration and scan timing at CT: considerations and approaches. Radiology 256:32–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narula J, Nakano M, Virmani R et al. (2013) Histopathologic characteristics of atherosclerotic coronary disease and implications of the findings for the invasive and noninvasive detection of vulnerable plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol 61:1041–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlett CL, Maurovich-Horvat P, Ferencik M et al. (2013) Histogram analysis of lipid-core plaques in coronary computed tomographic angiography: ex vivo validation against histology. Invest Radiol 48:646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimura S, Sugiyama T, Hishikari K et al. (2015) Association of intravascular ultrasound- and optical coherence tomography-assessed coronary plaque morphology with periprocedural myocardial injury in patients with stable angina pectoris. Circ J 79:1944–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura S, Sugiyama T, Hishikari K et al. (2018) The clinical significance of echo-attenuated plaque in stable angina pectoris compared with acute coronary syndromes: a combined intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography study. Int J Cardiol 270:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.