Abstract

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is both prevalent and unavoidable in many people as a result of persistent or unalterable risk factors, the most important of which are advanced age, excess body weight, and family history. Given this inevitability, medical treatment is required to alleviate symptoms and slow disease progression. Venoactive drug therapy is emerging as a valuable treatment option for many CVD patients and micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) is the most widely prescribed and well-studied venoactive drug available. Recent evidence from animal models of venous hypertension and from clinical trials, as well as from systematic reviews, shows that MPFF is effective at alleviating many of the most common symptoms of CVD including leg pain, leg heaviness, sensations of swelling, cramps, and functional discomfort. In addition, MPFF improves the clinical signs of redness, skin changes, and edema, and improves quality of life. Collectively, these findings support the strong recommendation for MPFF treatment found in the 2018 international guidelines for the management of CVD.

Funding: Servier.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-019-0884-4.

Keywords: Cardiology, Chronic venous disease, Chronic venous insufficiency, Flavonoid, Inflammation, Micronized purified flavonoid fraction, MPFF, Venoactive drugs, Venous hypertension

Talking Head Video. (MP4 88237 kb)

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video abstract and summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7599164.

Introduction

As a result of the number of confirmed and prevalent risk factors, such as family history, high body mass index, advanced age, and reduced mobility, symptomatic chronic venous disease (CVD) is inevitable in many people and imposes tremendous burdens on patient health and quality of life (QoL), as well as on healthcare systems [1–5]. In addition to compression therapy and surgical interventions, venoactive drugs (VAD) are emerging as valuable additions to the therapies available to physicians to treat CVD patients [6]. Among these, micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; 90% diosmin and 10% concomitant active flavonoids) is the most widely prescribed VAD in Europe, but what is the recent evidence for its current grade A status and strong recommendation in CVD management guidelines?

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Pathophysiology of CVD

The development and progression of CVD involves a complex cycle of venous hypertension and inflammation [7–9]. Briefly, chronic venous hypertension and dilatation precipitate pathophysiological changes in vein walls and valves. Altered venous flow results in abnormal shear stresses in the vein that trigger initial inflammatory responses, endothelial cell activation, as well as leukocyte adherence, activation, and infiltration. In time, endothelial permeability increases allowing red blood cell extravasation into surrounding tissues. Subsequent red blood cell breakdown activates mast cells and macrophages, which release additional inflammatory mediators. TGF-β1 and other proinflammatory cytokines stimulate collagen synthesis, which increases vascular wall thickening and remodeling, and leads to further venous deterioration, dysfunction, and inflammation.

Effects of MPFF Treatment

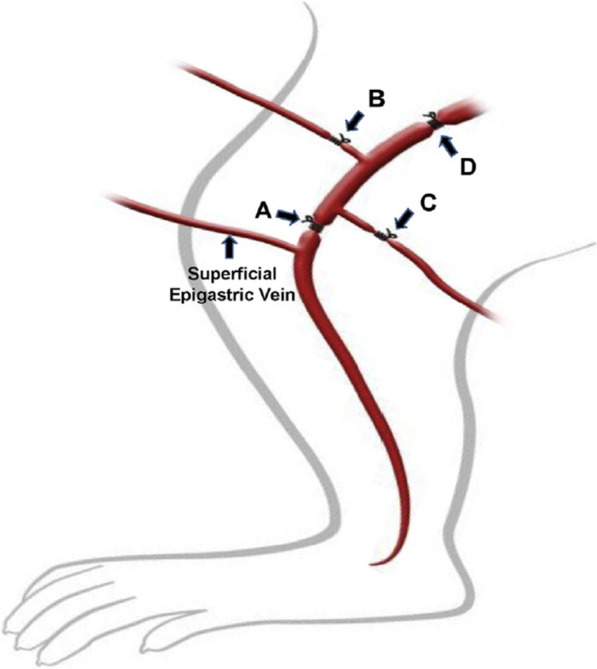

In a recent investigation into the pharmacological effects of MPFF, das Graças C de Souza et al. employed a long-term model of chronic venous hypertension with low venous flow in which the femoral vein and its branches, or the iliac vein, of hamsters were surgically ligated and animals were treated or not treated with MPFF for up to 10 weeks (Fig. 1) [10]. Epigastric venous pressure progressively increased in the weeks following vein ligations, and led to pathological changes in the microvasculature and inflammatory responses that resemble those found in CVD [8–11]. MPFF treatment (100 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks prior to vein ligation and for 6 weeks thereafter) significantly and effectively prevented the increases in leukocyte rolling (p < 0.001) and leukocyte adherence (p < 0.001) found in the ligated veins of control-treated animals. MPFF also significantly prevented the decrease in functional capillary density (p < 0.001) and the increase in venular diameter (p < 0.004) caused by the ligations. The combined components of MPFF appeared to have a synergistic effect because MPFF was more effective than either diosmin or the active flavonoids alone. These results indicate that MPFF acts to prevent some of the earliest inflammatory consequences of venous hypertension, as well as early changes in the microvasculature, suggesting that treatment of early stage CVD could help prevent or slow disease progression. As with any animal model, these results must be confirmed in clinical studies in patients with CVD.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of ligature models. A Right femoral vein above the origin of superficial epigastric vein; B origin of right branch of femoral vein; C origin of left branch of femoral vein; and D upper third of right external iliac vein. Reproduced with permission from das Graças C de Souza M, Cyrino F, de Carvalho J. et al. Protective Effects of Micronized Purified Flavonoid Fraction (MPFF) on a Novel Experimental Model of Chronic Venous Hypertension. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:694–702 [10]

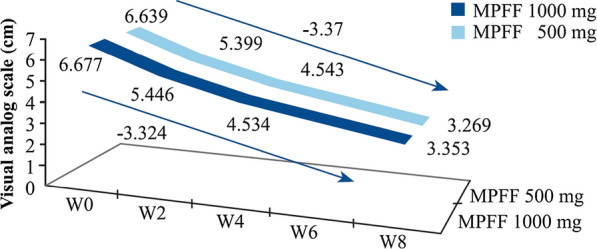

There is also new clinical evidence confirming that MPFF treatment improves CVD symptoms in patients, and treatment with 1000 mg once per day may be sufficient. In a randomized, double-blind study in 174 CVD patients (C0s to C4) comparing MPFF treatment at 500 mg twice per day to 1000 mg once per day, patients in both treatment groups reported significant and similar reductions in leg pain assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) beginning after 2 weeks of treatment [12]. Pain continued to significantly improve in both treatment groups through weeks 4 and 8, with no significant differences between groups. Another randomized, double-blind study in 1076 CVD patients (C0s to C4) compared these same two dosing regimens for 8 weeks and found significant and similar reductions in the CVD symptoms of lower limb discomfort, leg pain, and leg heaviness in both treatment groups (Fig. 2) [13]. This study also found that QoL, as measured by the CVD-specific CIVIQ-20 test, improved by approximately 20 points with either treatment. These studies illustrate that MPFF progressively improves symptoms and QoL in CVD patients.

Fig. 2.

Lower limb discomfort progressively and significantly improves in patients with C0s–C4 CVD. Patients were treated with 1000 mg MPFF suspension × 1/day or 500 mg tablet × 2/day for 8 weeks. Leg discomfort was assessed weekly by visual analog scale. Reprinted by permission of Edizioni Minerva Medica from: International Angiology 2017 October;36(5):402–9 [13]

In a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials investigating the effects MPFF on CVD signs and symptoms, and QoL, Kakkos and Nicolaides identified seven double-blind, placebo-controlled studies comprising a total of 1692 patients with CVD [14]. In qualitative analysis of MPFF treatment compared to placebo, they found mostly high-quality evidence that MPFF substantially and significantly improved nine different leg symptoms including pain, heaviness, feeling of swelling, cramps, and functional discomfort, with standard mean differences between − 0.25 and − 0.99. In quantitative analysis of categorical variables, MPFF reduced leg pain (risk ratio [RR] 0.53), heaviness (RR 0.35), feeling of swelling (RR 0.39), cramps (RR 0.51), paresthesia (RR 0.45), and functional discomfort (RR 0.41). Notably, the number of patients that needed to be treated (NNT) with MPFF to observe improvement in one patient was less than 5 for any symptom—a remarkably low number. MPFF was also highly effective for improving QoL and objective signs of edema and leg redness.

The VEIN ACT Program was a large prospective, international, observational study sponsored by the European Venous Forum and Servier (France) designed to assess the effects and compliance of conservative, non-surgical CVD treatments in a real-world setting [15, 16]. Across seven regions/countries (Russia, Spain, Romania, Colombia, Austria, West Indies, and Central America), CVD outpatients consulting for lower limb pain or any clinical presentation related to CVD were enrolled and assessed for CEAP classification, symptoms present, and symptom intensity. Most patients were given lifestyle advice and conservatively treated with various combinations of VAD (including MPFF), pain medications, and compression. In Colombia, 1570 patients were enrolled by general practitioners, 80% were women, the mean age was 59 years, and mean BMI was 27 ± 4 kg/m2 [15]. Most patients (55%) were classified as C2 or C3 and the most frequent symptoms were leg pain (85%), leg heaviness (79%), sensation of swelling (57%), and cramps (46%), of which most patients (68%) reported having regularly (i.e., for most of the day). After approximately 60 days of conservative treatment, which included a VAD (mostly MPFF) for 99% of the patients, compression for 49%, and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for 16%, patients reported that symptom intensity had improved by at least 50% on the VAS for all four symptoms. Similar results were obtained for 1460 patients enrolled and treated comparably by vascular surgeons. In Russia, 1607 patients were enrolled in the program, of which 68% were C2 or C3 [16]. Of these, 1368 patients received combined treatment and a smaller cohort of 89 patients received treatment with MPFF alone. Symptom intensity for leg pain, leg heaviness, sensation of swelling, and cramps as assessed by VAS all improved significantly by approximately 50% in both groups (p < 0.0001). Symptom frequency also improved significantly in both groups (p < 0.0001), and over 95% of the patients were rather, very, or extremely satisfied with either treatment regimen. Although the VEIN ACT program is not a controlled study, these results indicate that treatment with a VAD, including MPFF, either alone or combined with other conservative treatments, is effective in real-world settings and that most CVD patients are satisfied with the results of the treatment.

MPFF treatment may also be effective in patients with early stage CVD who exhibit situational great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux [17]. In patients with C0s or C1s (n = 46), MPFF treatment (1000 mg per day for 90 days) eliminated evening GSV reflux in 76%, significantly decreased evening GSV diameters (p < 0.0001), and significantly reduced the intensity of VAS-assessed leg heaviness from 5.2 cm to 1.7 cm (p < 0.0001). In addition, reductions or elimination of patient symptoms corresponded with the elimination of situational GSV reflux. Elimination of situational GSV reflux in the majority of patients with early stage CVD provides another line of evidence that MPFF could help prevent CVD progression.

In the recently updated management guidelines for CVD of the lower limbs, MPFF has been given strong recommendations [6]. These guidelines were issued jointly by the European Venous Forum, the Cardiovascular Disease Educational and Research Trust (UK), the Union Internationale de Phlebologie, and the International Union of Angiology according to the available clinical evidence. Primarily on the basis of the recent meta-analysis [14], MPFF was considered to have A-grade levels of evidence for effectiveness in reducing the intensity of CVD symptoms of pain, heaviness, feeling of swelling, and functional discomfort, and of skin changes (Table 1). Other VAD, such as Ruscus aculeatus extract combined with hesperidin methyl chalcone (HMC) and ascorbic acid, and horse chestnut seed extract, also received some A grades for pain, heaviness, and swelling. However, MPFF was the only VAD to receive an A grade for improvements in skin changes and QoL. High-quality evidence was also found for MPFF, pentoxifylline, and sulodexide treatments in improving leg ulcer healing. As a result of this extensive high-quality evidence, strong recommendations were made for MPFF for effective treatment of pain, heaviness, feeling of swelling, functional discomfort, cramps, leg redness, skin changes, edema, and QoL [6].

Table 1.

Level of evidence that merits grade A or B for the effect of the main VADs on individual symptoms, signs, and QoL with magnitude of effect

| Symptom/sign | Venoactive drugs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPFF | Ruscus + HMC + AA | Oxerutins | HCSE | Calcium dobesilate | |

| Pain (NNT; SMD) | A (4.2; − 0.25) | A (5; − 0.80) | B (–; − 1.07) | A (5.1; –) | B (1; –) |

| Heaviness (NNT; SMD) | A (2.9; − 0.80) | A (2.4; − 1.23) | B (17; − 1.00) | A (1; –) | |

| Feeling of swelling (NNT; SMD) | A (3.1; − 0.99) | A (4; −2.27) | |||

| Functional discomfort (NNT; SMD) | A (3.0; − 0.87) | B (4; –) | |||

| Leg fatigue (SMD) | NS | B (− 1.16) | |||

| Cramps (NNT; SMD) | B (4.8; − 0.46) | B/C | B (–; − 1.7) | ||

| Paresthesia (NNT; SMD) | B/C (3.5; − 0.11) | A (1.8; − 0.86) | B (2; –) | ||

| Burning (SMD) | B/C (− 0.46) | NS | |||

| Pruritis/itching (NNT) | B/C | A (6.1) | |||

| Tightness | NS | ||||

| Restless legs | NS | ||||

| Leg redness (NNT; SMD) | B (3.6; − 0.32) | ||||

| Skin changes (NNT) | A (1.6) | ||||

| Ankle circumference (NNT; SMD) | B (–; − 0.59) | A (–; − 0.74) | NS | A (4; –) | |

| Foot or leg volume (SMD) | NS | A (–; − 0.61) | NS | A (− 0.34) | A (− 11.4) |

| QoL (SMD) | A (− 0.21) | NS | |||

The number needed to treat (NNT) to benefit one patient and/or the standardized mean difference (SMD) are also shown. Only randomized placebo controlled trials and meta-analyses were considered

HSCE horse chestnut seed extract, MPFF micronized purified flavonoid fraction, NS not significant, QoL quality of life, Ruscus + HMC + AA Ruscus aculeatus extract, hesperidin methyl chalcone, and ascorbic acid. Reprinted by permission of Edizioni Minerva Medica from: International Angiology 2018 June;37(3):181–254 [6]

Conclusions

In animal models and in clinical trials, MPFF has been shown to prevent the inflammatory consequences and microcirculatory dysfunction precipitated by chronic venous hypertension, and to break the vicious cycle of venous inflammation that can lead to patient discomfort, skin changes, and venous ulcers. Abundant high-quality evidence exists that MPFF is highly effective for treating the symptoms and signs of CVD, and that it improves QoL at all CEAP stages. This evidence merits the highest strength of recommendations for MPFF treatment now found in the 2018 management guidelines for CVD [6]. Future studies should focus on the cost-effectiveness of MPFF treatment, and whether it can help reduce the substantial burden of CVD on patients and healthcare systems.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This supplement has been sponsored by Servier. Article processing charges and the open access fee were funded by Servier. The author had full access to all of the data for this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing

The medical writing services were provided by Dr Kurt Liittschwager (4Clinics, France) and was funded by Servier.

Authorship

Jorge H. Ulloa meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has approved this version for publication.

Prior Presentation

This article and all of the articles in this supplement are based on the International satellite symposium at European Venous Forum, June 29th, Athens.

Disclosures

The symposium was funded by an educational grant from Servier. Jorge H. Ulloa received honoraria from Servier for the symposium lecture, and in the past for serving on the Servier speaker bureau.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7599164.

Change history

7/3/2021

A peer-reviewed talking head video was retrospectively added to this publication

References

- 1.Fowkes FG, Evans CJ, Lee AJ. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology. 2001;52(Suppl 1):S5–S15. doi: 10.1177/0003319701052001S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jawien A. The influence of environmental factors in chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology. 2003;54(1):S19–S31. doi: 10.1177/0003319703054001S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pannier F, Rabe E. Progression in venous pathology. Phlebology. 2015;30(1 Suppl):95–97. doi: 10.1177/0268355514568847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson LA, Evans CJ, Lee AJ, Allan PL, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. Incidence and risk factors for venous reflux in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onida S, Davies AH. Predicted burden of venous disease. Phlebology. 2016;31(1):74–79. doi: 10.1177/0268355516628359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, Comerota A, de Maesenner M, Eklof B, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines according to scientific evidence part I. Int Angiol. 2018;37(3):181–254. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.18.03999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schonbein GW, Smith PD, Nicolaides AN, Boisseau MR, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):488–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansilha A, Sousa J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease and implications for venoactive drug therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:6. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pocock ES, Alsaigh T, Mazor R, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Cellular and molecular basis of venous insufficiency. Vasc Cell. 2014;6(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13221-014-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.das Graças C de Souza M, Cyrino FZ, Carvalho JJ, Blanc-Guillemaud V, Bouskela E. Protective effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) on a novel experimental model of chronic venous hypertension. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(5):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro-Ferreira R, Cardoso R, Leite-Moreira A, Mansilha A. The role of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in chronic venous disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;46:380–393. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirienko A, Radak D. Clinical acceptability study of once-daily versus twice-daily micronized purified flavonoid fraction in patients with symptomatic chronic venous disease: a randomized controlled trial. Int Angiol. 2016;35(4):399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpentier P, van Bellen B, Karetova D, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of a new 1000-mg suspension versus twice-daily 500-mg tablets of MPFF in patients with symptomatic chronic venous disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Int Angiol. 2017;36(5):402–409. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.17.03801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakkos SK, Nicolaides AN. Efficacy of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon®) on improving individual symptoms, signs and quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Int Angiol. 2018;37(2):143–154. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.18.03975-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulloa JH, Guerra D, Cadavid LG, Fajardo D, Villarreal R, Bayon G, et al. Nonoperative approach for symptomatic patients with chronic venous disease: results from the VEIN Act program. Phlebolymphology. 2018;25(2):123. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lishkov DE, Kirienko AI, Larionov AA, Chernookov AI. Patients seeking treatment for chronic venous disorders: Russian results from the VEIN Act program. Phlebolymphology. 2016;23(1):44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY. Diagnosis and treatment of situational great saphenous vein reflux in daily medical practice. Phlebolymphology. 2017;24(3):144–151. [Google Scholar]