Abstract

Introduction

Adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS) is a surgical device developed to treat male stress urinary incontinence (SUI) after prostate surgery. The objective was to assess the effectiveness of the ATOMS device to treat male SUI as described in the literature.

Methods

Two independent reviewers identified studies eligible for a systematic review and meta-analysis of various sources written in English, German and Spanish, using the databases PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science. We excluded studies on female incontinence. We employed the DerSimonian and Laird method for defining heterogeneity, calculating the grouped standard mean deviation (SMD). The primary objective of this review is the assessment of clinical efficacy based on the achievement of dryness after device adjustment, defined as use of no pad or one safety pad per day (PPD). The secondary objective was focused on analysing improvement of incontinence with the device. Magnitude of effect was calculated by analysing decrease in pad count (PPD) and/or in 24-h pad test. Number and severity of complications according to Clavien–Dindo classification were also reviewed.

Results

The pooled data of 1393 patients from 20 studies (13 retrospective and 7 prospective) showed that treatment with ATOMS resulted in a mean 67% dryness rate and 90% improvement after adjustment. Mean total number of system fillings per patient was 2.4. Mean pad count and 24-h pad test decrease were − 4.14 PPD and − 443 cc, respectively. There is significant heterogeneity of the sample analysed, mainly based on variable baseline severity of incontinence, proportion of patients treated with irradiation and different generation devices. Proportion of irradiated patients affected dryness rate (p = 0.0014), together with baseline severity of incontinence (p = 0.0035) and different generation device used (p < 0.0001). Standardized mean follow-up was 20.9 months, with complications occurring in 16.4% (major complications 3.0%) and explantations in 5.75%. No randomized study has been developed so far to compare ATOMS to other devices for treating male SUI.

Conclusion

Despite the evidence being exclusively based on descriptive studies and limited follow-up, ATOMS has proven to be a safe alternative to treat different degrees of male SUI after prostate surgery. Better results are evidenced for patients with less than 6 PPD before implantation, non-irradiated patients and use of third-generation device with silicone-covered pre-attached scrotal port.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0852-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adjustable transobturator male system, Effectiveness, Male stress urinary incontinence, Postprostatectomy incontinence, Safety, Urology

Introduction

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is one of the sequelae with the greatest negative impact on the quality of life of the patient after prostate surgery, mainly due to prostate cancer surgery but also for benign pathology, despite the continuous improvements in the surgical techniques [1]. Some of the most determinant risk factors are pre-existing bladder dysfunction, the age of the patient and previous radiotherapy [2]. The negative impact of significant SUI on the quality of life of patients suffering prostate cancer can only be palliated by prosthetic surgery.

Classically the gold standard treatment after failure of conservative therapy for male SUI has been the artificial urinary sphincter (AUS), despite its high rate of complications and explantations [3, 4]. The development in recent years of male slings, which reposition the posterior urethra, has been a great revolution, as they offer a less invasive surgical approach with low rate of complications. The severity of male SUI to be treated with a retrobulbar sling is mild-to-moderate, exclusively. Further development of adjustable slings with the possibility of postoperative adjustment has widened the spectrum of SUI severity that can be treated with the transobturator perineal approach. Different devices are now available to allow a personalised surgical approach for male SUI [1, 5–7].

Adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS®, Agency for Medical Innovations GmbH, Feldkirch, Austria) is a device that allows the bulbar urethra to be compressed only on one side. The device can be easily adjusted postoperatively in the office. It is composed of a central silicone cushion connected to a port and a two-arm mesh that is anchored to the cushion through a transobturator passage on both sides of the pubis. The compression of the urethra is performed ventrally and can be progressively adjusted postoperatively by filling or emptying the cushion with a simple injection of sterile saline solution into the port. There is no need for anaesthesia during adjustment. It opens a new perspective of treatment for patients with male SUI of any degree, and it may be the best option in patients with limited dexterity or cognitive impairment, as no manipulation is required [8, 9]. Unfortunately, we do not have comparative studies between the AUS and adjustable or non-adjustable slings, which could help the selection of the ideal patient for each device [1, 10].

ATOMS was developed in 2008. The first generation consisted of a titanium inguinal port (IP) and required two incisions for placement [11]. The device was modified in 2013 to include a scrotal port (SP), and the third-generation device with pre-attached silicone-covered scrotal port (SSP) was introduced in 2014. The evolution of inguinal to scrotal port has allowed one to perform a single incision, thus lowering the risk of infection and facilitating postoperative adjustment [8, 9, 12]. Interest in the use of ATOMS is increasing, as it is a simple alternative with high rate of dryness and very high rate of satisfaction reported. Besides, the adjustable sling concept is used not only in mild-to-moderate SUI as for male retrourethral slings but it is also extending its indication to patients with severe SUI [12].

A number of studies with ATOMS have been published in peer-reviewed journals in recent years, but tend to be single-centre or multicentre initial experiences with limited follow-up [8, 9, 11, 13–28]. Randomized comparative studies with other devices have not been performed and, to date, no systematic review or meta-analysis has been published on the subject. Our review aims to evaluate the current evidence on the effectiveness and safety of the ATOMS® device in the treatment of male SUI after prostate surgery.

Methods

A systematic review of the scientific literature was carried out in August 2018. This search included studies published between January 1, 2008 and July 31, 2018. The search was undertaken in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus. The search strategy was designed according to PICOS criteria (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes and Study Design) (Table 1) for the identification of studies using free and controlled terminology. The search strategy included the terms “Urinary incontinence” AND “male” AND “ATOMS”. A manual revision of the bibliographic references of the documents found electronically was also carried out. We included prospective and retrospective, multicentre or single-centre case series, published in English, Spanish or German on patients treated with the ATOMS device for SUI after prostate surgery. Duplicate studies, editorial comments, letters to the editor or expert opinions in non-systematic reviews were excluded. This review article is an independent paper. A review protocol was not published before conducting the review.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria to guide the systematic review

| Population | Male patients with mild, moderate or severe stress urinary incontinence after prostate surgery, either previously radiated or not and also treated primarily or after failure of other surgical devices |

| Intervention | Placement of ATOMS® device |

| Comparison | None available |

| Outcomes |

Primary: Overall dryness rate (no pad or one security pad per day) Secondary: Overall improvement rate, differential pad count and/or pad test (after adjustment with respects to baseline) and complication rate |

| Study design | Retrospective and prospective case series |

The primary effectiveness indicator was percentage of dryness achieved, defined as patients using no pad or only one safety pad per day (PPD). The main secondary effectiveness outcome was percentage of overall improvement (defined as any decrease in pad count and/or in 24-h pad test). Also differential pad count and differential 24-h pad test between baseline and after adjustment were investigated to evaluate the magnitude of effect. The definitions of postoperative dryness were comparable, considering a dry patient using no pad or one safety pad per day. The definition of improvement was urine loss under baseline at the time of adjustment. Differential pad count or 24-h pad test was calculated as after adjustment minus baseline when available, assuming both values are independent. The percentage of explantations, complications, major complications (defined as Clavien–Dindo classification Grade III or more) [29] and transient dysesthesia were evaluated as safety indicators. Number of adjustments, the proportion of patients with previous anti-incontinence surgery and the proportion of patients satisfied with the intervention were also evaluated. All outcomes were tested by comparing follow-up data to baseline date, i.e. within-group effects, because of a lack of comparison groups.

The identification, selection and extraction of data from the studies were carried out exhaustively and independently by two reviewers. A first selection of the studies was performed by reading the title and the abstract, and those that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed by reading the full text. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or in collaboration with another member of the research team. The evidence was summarized with the data extracted from the studies that included bibliographic information, characteristics of the study and patients, characteristics of the intervention, and outcome measures in relation to the effectiveness and safety of the procedure.

Pooled proportion, mean and difference mean with the corresponding 95% CIs were used as the summary effect measure. Freeman–Tukey transforms were used to compare proportions. The heterogeneity assumption was evaluated by the Chi-square-based Cochran’s Q test (which was considered significant at p < 0.05) and quantified with the I2 statistic (with values < 25%, 25% to 75%, and > 75% interpreted as representing low, moderate and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively). Random-effects model with the inverse variance method was used for pooling results from primary studies in the presence of significant heterogeneity; for the remaining studies, a fixed-effects model was applied. The DerSimonian and Laird method was used to model heterogeneity by calculating the weighted mean difference for continuous variables. All results were described as standard mean deviation (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots and quantified by Egger’s linear regression test. Statistical analysis and figures were generated with the meta package of R software version 3.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [30, 31]. In accordance with compliance with ethics guidelines, this article is based on previously conducted studies and is not itself a study with human participants or animals.

Results

Literature Search

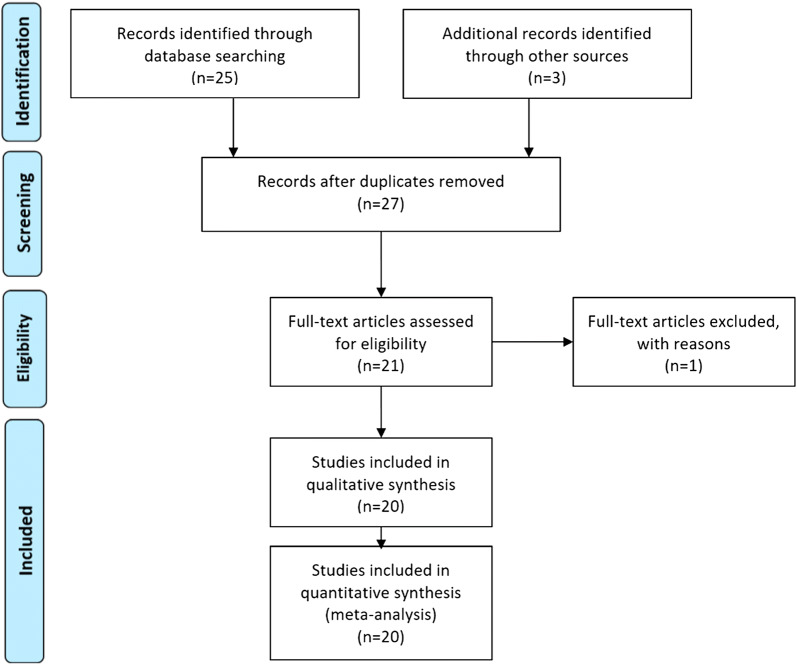

In a first phase, a total of 28 references were identified. After we read the title and the abstract, one study was excluded because of duplication and six studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Another study gave a description of the operative technique but did not provide information to be included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart defining studies included in this systematic review

Characteristics of the Studies

The main characteristics of the 20 selected studies are presented in Table 2. These studies were published between 2011 and 2018, and collected the experience of 1393 patients in total. Thirteen (seven multicentre) studies were retrospective and seven (three multicentre) prospective. None was a randomized controlled study. They included different causes of SUI (mainly after prostatectomy), a varied percentage of irradiated patients and different degree of baseline incontinence according to 24-h pad test (cc) and/or pad count (pads per day or PPD).

Table 2.

Studies included in the meta-analysis on adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS) to treat male stress urinary incontinence

| Author year (reference) | Number of patients | PPI (%) | Radiation (%) | Dry rate (%) | Definition of dryness | Improved rate (%) | Number of adjustments | Satisfied rate (%) | Explant rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer and Brössner 2011 [11] | 120 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hoda et al. 2012 [13] | 124 | 100 | 34.7 | 61.6 | 0–1 PPD | 93.8 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | NA | 4 |

| Seweryn et al. 2012 [14] | 38 | 94.7 | 44.7 | 60.5 | 0–1 PPD < 15 mL | 84.2 | 3.97 (0–9) | NA | 10.5 |

| Hoda et al. 2013 [15] | 99 | 93 | 31.7 | 63 | 0–1 PPD < 10 mL | 92 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | NA | 4 |

| Krause et al. 2014 [16] | 36 | 75 | 39 | 39 | 0–1 PPD | 50 | NA | 61.8 | 30.5 |

| González et al. 2014 [17] | 13 | 92.3 | 7.7 | 92.3 | 0 PPD | 87.1 | NA | 100 | 0 |

| Friedl et al. 2016 [18] | 34 | 88.2 | 26.5 | 56 | 0–1 PPD | 88 | NA | NA | 11.8 |

| Mühlstädt et al. 2016 [19] | 54 | 75.8 | 31.5 | 48.1 | 0 PPD | 77.7 | 4.5 ± − 2.3 | NA | 7.4 |

| Friedl et al. 2016 [20] | 62 | 90.3 | 32.2 | 61.3 | 0–1 PPD | 90 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | NA | 14.5 |

| El Badry et al. 2016 [21] | 9 | 33.3 | NA | 77.8 | 0 PPD | 89.9 | 1 | NA | 0 |

| Hüsch et al. 2016 [22] | 49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.0 |

| Buresova et al. 2017 [23] | 35 | 97.1 | 25.7 | 62.9 | 0–1 PPD | 100 | 4.3 (1–15) | NA | 2.9 |

| Friedl et al. 2017 [24] | 287 | 86.4 | 23.3 | 64 | 0–1 PPD < 10 mL | NA | 3 (2–4) | NA | 19.5 |

| Friedl et al. 2017 [25] | 49 | 0 | 16.3 | 57.1 | 0–1 PPD < 10 mL | 89.7 | 2 ± 1 | NA | 19.5 |

| Angulo et al. 2017 [8] | 34 | 100 | 8.8 | 85.3 | 0–1 PPD | 95 | 1 ± 3 | 97 | 0 |

| Manso et al. 2018 [26] | 25 | 92 | 44 | 64 | 0–1 PPD | 100 | 1.54 ± 1.3 | 84 | 0 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [12] | 215 | 92.1 | 20 | 80.5 | 0–1 PPD < 10 mL | 85,1 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 85.1 | 3.25 |

| Esquinas et al. 2018 [9] | 60 | 90 | 8.3 | 81.7 | 0–1 PPD | 93.3 | 1 ± 2 | 93.2 | 1.7 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [27] | 20 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 0–1 PPD | 91.5 | 1 ± 3 | 80 | 0 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [28] | 30 | 86.7 | 20 | 76.7 | 0–1 PPD | 100 | 1 ± 1 | 83.3 | 3.3 |

| Author year (reference) | Complication rate (%) | Major complication rate (%) | Transient dysesthesia (%) | Baseline pad count (PPD) |

Post adj. pad count (PPD) | Baseline pad test (cc/day) |

Post adj. pad test (cc/day) | Previous surgery (%) | Mean follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer and Brössner 2011 [11] | NA | NA | 62 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 43 | |

| Hoda et al. 2012 [13] | 8.9 | NA | 60.5 | 8.8 ± 3.8 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 725 ± 372 | NA | NA | 19.2 ± 2.2 |

| Seweryn et al. 2012 [14] | NA | 15.8 | 52.6 | 6.78 (2–10) | 1.36 (0–10) | 747 (230–1600) | 115 (0–1500) | 28.9 | 16.9 |

| Hoda et al. 2013 [15] | NA | NA | 68.7 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 681 ± 466 | 79.7 ± 210 | 34.3 | 17.8 ± − 1.6 |

| Krause et al. 2014 [16] | 44.4 | NA | 29.4 | 8.33 | 4.4 | NA | NA | 30.5 | NA |

| González et al. 2014 [17] | NA | NA | 23.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15.4 | 16 (4–32) |

| Friedl et al. 2016 [18] | 17.6 | NA | ND | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | NA | NA | 29.4 | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| Mühlstädt et al. 2016 [19] | 25.9 | NA | 5.6 | 7.7 ± 4.8 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | NA | NA | 20.4 | 27.5 ± 18.4 |

| Friedl et al. 2016 [20] | 6.45 | NA | NA | 4 (3–5) | 1 (0–2) | 350 (300–542) | 5 (0–135) | 27.4 | 17.7 (1.7–55.5) |

| El Badry et al. 2016 [21] | 22.2 | NA | 66.7 | 4.6 (3–6) | 0 (0–2) | 747 (230–1600) | NA | NA | 9 (6–12) |

| Hüsch et al. 2016 [22] | 14.2 | 2.0 | 4.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Buresova et al. 2017 [23] | 20 | NA | 40 | 5 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 21.2 (3–63) |

| Friedl et al. 2017 [24] | 7 | 2 | NA | 4 (3–5) | 1 (0–2) | 400 (300–700) | 18 (0–105) | NA | 31 (10–54) |

| Friedl et al. 2017 [25] | 34.7 | 16.3 | NA | 4 (3–6) | 1 (0–2) | 458 (310–630) | 10 (0–90) | 16.3 | 32 ± 8.5 |

| Angulo et al. 2017 [8] | 14.7 | NA | NA | 5 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 510 ± 500 | 0 ± 15 | 11.8 | 18.5 ± 10 |

| Manso et al. 2018 [26] | NA | 4 | 32 | 4.84 ± 2.95 | 1.6 ± 2.02 | NA | NA | 12 | 21.56 ± 8.89 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [12] | 15.3 | 3.7 | NA | 3.9 ± 2 | 0.9 ± 1.5 | 484 ± 372 | 63.5 ± 201 | 5.6 | 24.3 ± 15 |

| Esquinas et al. 2018 [9] | 18.6 | NA | 10 | 5 ± 3 | 0 ± 1 | 465 ± 450 | 0 ± 20 | 6.7 | 21 ± 22 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [27] | 15 | NA | NA | 4 ± 3 | 0 ± 1.5 | 375 ± − 855 | 10 ± 32.25 | 10 | 38.5 ± 19.5 |

| Angulo et al. 2018 [28] | 13.3 | NA | NA | 4 ± 3 | 0 ± 1 | 435 ± 393 | 10 ± 30 | 100 | 21 ± 22 |

NA not available

The Freeman–Tukey arcsine transformation was developed for binomial-like data, in particular, data representing proportions or percentages. Pooled proportion (dryness, improvement and complication rates) and mean (differential pad count and differential pad test, comparing baseline and after adjustment) with the corresponding 95% CIs were used as summary effect measure (Figs. S1–S5).

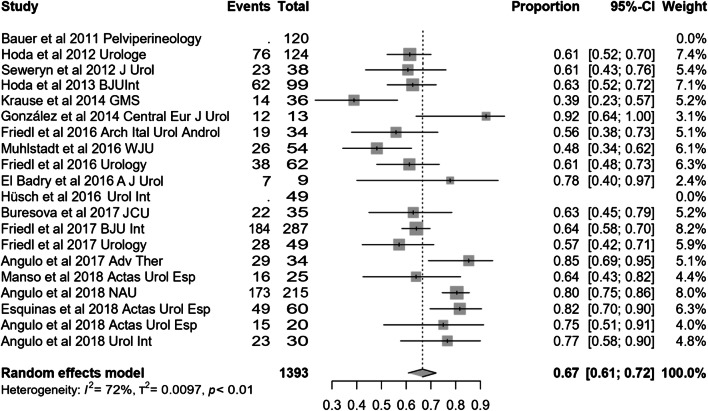

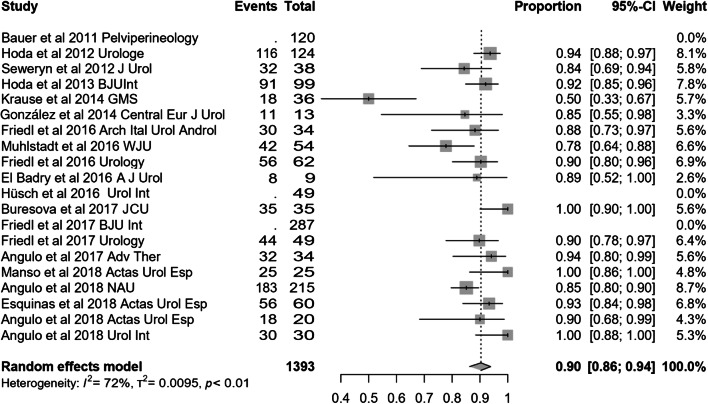

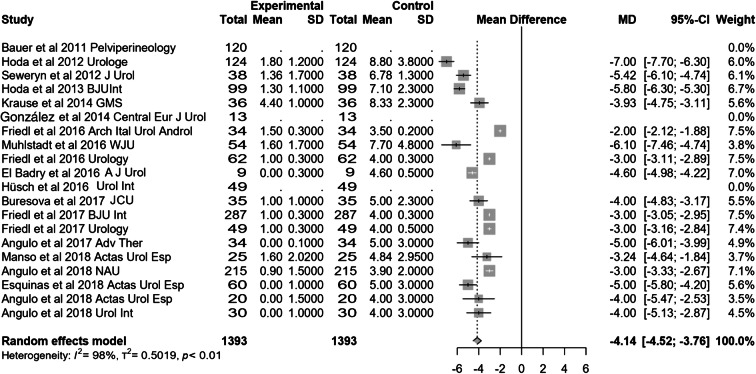

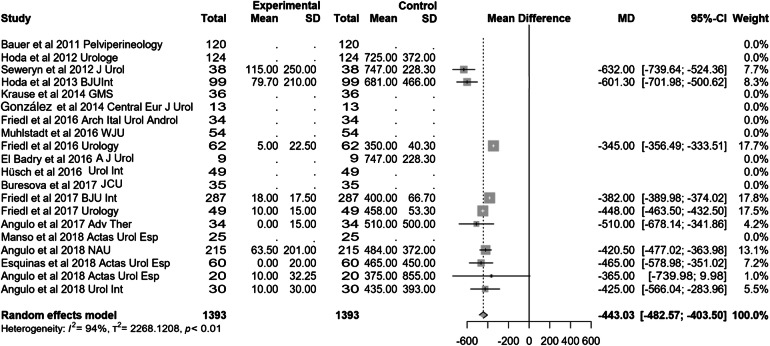

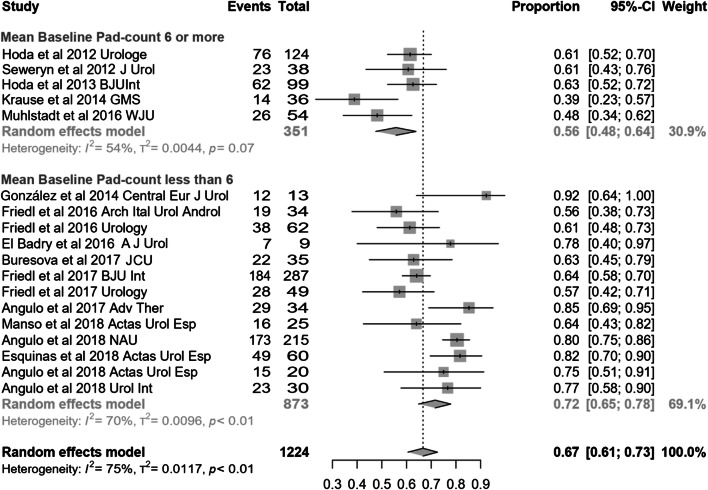

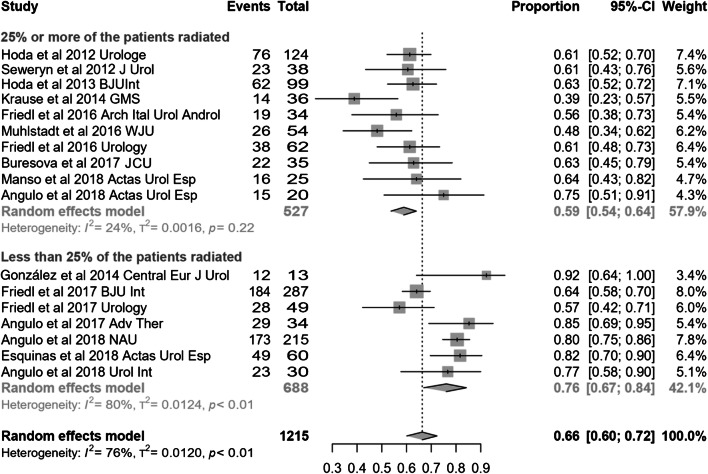

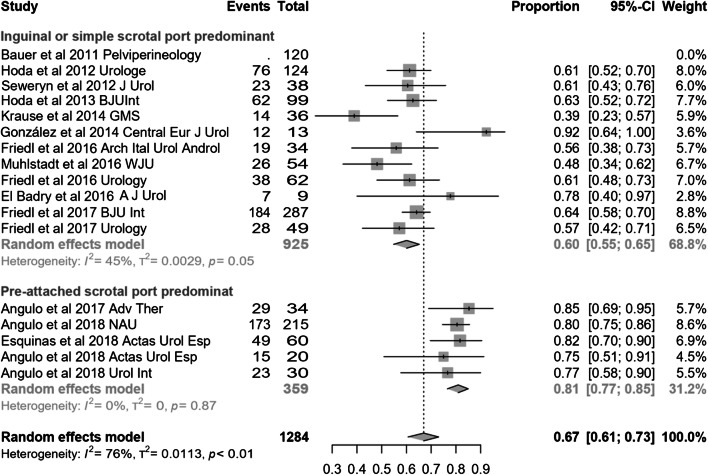

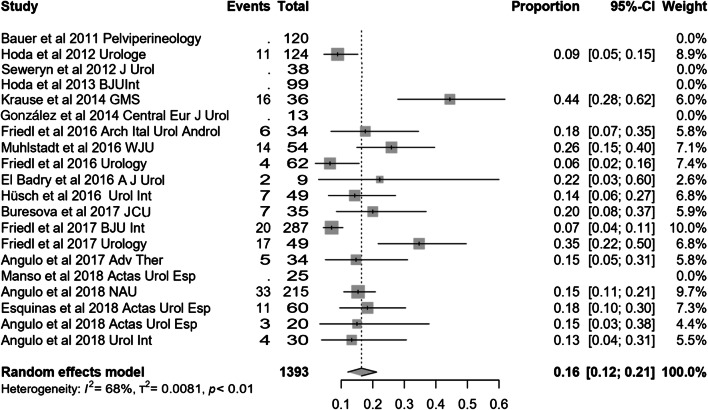

Effectiveness

Most of the studies included presented effectiveness results expressed by global dryness rate (with a very similar definition), improvement rate and quantitative data of the effect based on pad count (baseline, after adjustment and differential). Information concerning 24-h pad test is less uniform and lacking in some studies. Occasionally, the proportion of patients that self-considered satisfied with the device is also available. Treatment with ATOMS resulted in a mean 67% (95% CI 0.61–0.72) dryness rate and 90% (95% CI 0.86–0.94) improvement after adjustment was considered complete (Figs. 2, 3). Mean total number of system fillings was 2.4 per patient (95% CI 1.8–2.9). The proportion of patients that had received previous surgical treatment for SUI was 25.5% (95% CI 16.2–36). The proportion of patients that self-declared satisfied with the procedure was 87% (95% CI 83–89.8). Mean baseline pad count reported was 5.21 PPD (95% CI 4.90–5.53), mean pad count after adjustment 1.08 PPD (95% CI 0.74–1.42) and mean differential pad count − 4.14 PPD (95% CI − 4.52 to − 3.76) (Fig. 4). Mean baseline 24-h pad test was 530.6 cc (95% CI 481.7–589.4), mean 24-h pad test after adjustment 13.3 cc (95% CI 5.7–20.9) and mean differential 24-h pad test − 443.0 cc (95% CI − 482.6 to − 403.5) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing dry rate in the studies analysed

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing improvement rate in the studies analysed

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing differential pad count expressed in pads per day in the studies analysed

Fig. 5.

Forest plot showing differential pad test expressed in cc in the studies analysed

Risk of publication bias was not identified for primary and main secondary effectiveness outcomes (Table S1). Significant heterogeneity of the sample analysed was noticed in most of the variables evaluated (Table S2). Heterogeneity was reduced when effectiveness data was stratified according to different variables. Dry rate, improvement rate, differential pad count and 24-h pad test between baseline and after adjustment were evaluated according to baseline severity of incontinence, proportion of irradiated patients and generation of the ATOMS device.

Studies with mean baseline pad count of at least 6 PPD (generally considered the definition of severe SUI) are compared with those with 5 or less PPD (mild-to-moderate SUI). Dry rate was 56% (95% CI 48–64) in studies with mean pad count of at least 6 and 72% (95% CI 65–78) in studies with mean pad count of less than 6, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0035) (Fig. 6). Regarding improvement a difference was also evidenced: 82% (95% CI 68–93) in studies with mean pad count of at least 6 and 93% (95% CI 90–96) in studies with mean pad count of less than 6, but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). Inverse and significant differences were observed in differential pad count and differential 24-h pad test (both p = 0.0001), thus revealing that the magnitude of effect was paradoxically larger in studies with mean baseline pad count of at least 6 PPD [− 5.64 PPD (95% CI − 6.58 to − 4.7) and − 615.6 cc (95% CI − 689.2 to −446.8)] than in studies with mean baseline pad count of less than 6 [− 3.48 PPD (95% CI − 3.83 to − 3.13) and − 408.1 cc (95% CI − 446.8 to − 369.4)].

Fig. 6.

Forest plot showing dry rate according to baseline severity of incontinence in the studies analysed

Studies were also stratified according to the proportion of irradiated patients they included. Those with at least 25% of the patients irradiated had worse dry rate than the rest [59% (95% CI 54–64) vs 76% (95% CI 67–84); p = 0.014] (Fig. 7), but differences were not found for improvement rate [89% (95% CI 81–95) vs 92% (95% CI 87–96); p = 0.56]. The magnitude of effect was superior for series with higher proportion of irradiation and this difference reached significance for pad count change [− 4.43 PPD (95% CI − 5.23 to − 3.62) vs. − 3.43 PPD (95% CI − 3.77 to − 3.1); p = 0.026], but not for 24-h pad test change [− 498 cc (95% CI −694 to − 303) vs. − 427 cc (95% CI −473 to − 382); p = 0.48].

Fig. 7.

Forest plot showing dry rate according to proportion of irradiated patients in the studies analysed

Studies with all or most of the patients treated with the latest generation device with SSP were also compared to studies that included the majority or all implants with IP and/or SP. Dry rate was 81% (95% CI 77–85) for series with predominant SSP and 60% (95% CI 55–65.2) for the rest (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8). Such a difference was not observed for improvement rate [93% (95% CI 86–98) vs 86% (95% CI 80–91); p = 0.096], differential pad count [− 4.17 PPD (95% CI − 5.22 to − 3.12) vs − 3.97 PPD (95% CI − 4.44 to − 3.5); p = 0.72] or differential 24-h pad test [− 433.8 cc (95% CI − 479.3 to − 388.3) vs 444.3 cc (95% CI 492.6 to − 396); p = 0.75].

Fig. 8.

Forest plot showing dry rate according to device generation in the studies analysed

Safety

Mean follow-up was 20.9 months (95% CI 16.5–25.3). Operative complications were not reported. Some degree of transient postoperative dysesthesia was reported in 35.6% (95% CI 86.5–93.1). Complications were reported in 16.4% (95% CI 12.1–21.2) (Fig. 9), and major complications in 3% (95% CI 1.65–21.2). The proportion of patients with device explanted was 5.75% (95% CI 2.8–9.5).

Fig. 9.

Forest plot showing complication rate in the studies analysed

Complication rate did not depend on baseline severity of incontinence: 23.4% (95% CI 10.5–39.4) in series with mean baseline pad count of at least 6 PPD vs. 14.8% (95% CI 10–20.3) for less than 6 PPD; p = 0.28. It did not depend on the proportion of irradiated patients: 17.8% (95% CI 10.8–26.1) for series with at least 25% of the patients irradiated vs. 15.6% (95% CI 8.8–23.7) for those with less than 25%; p = 0.68. Complication rate also did not depend on generation of the device: 15.15% (95% CI 11.5–19.2) in studies predominantly including SSP vs. 17.8% (95% CI 10.6–26.2) in those with predominant IP or SP; p = 0.54.

Discussion

The ATOMS device has been implanted in Europe for a decade. Its main advantages include the fact that there is no need for manipulation by the patient to carry out urination, minimal risk of mechanical failure owing to its simplicity and the option of simple postoperative adjustment without surgical intervention. All these characteristics surely contribute to a very high proportion of patients reporting satisfaction [8, 9, 12, 17]. This meta-analysis evaluates the effectiveness and safety of the ATOMS system to treat male SUI after prostate surgery. Quantitative summary estimates provided by this meta-analysis are 67% dryness, 90% improvement, 87% satisfaction, 5.75% explantation, 16% complications and 3% major complications. Noticeably, satisfaction rate and the proportion of subjects with major complications are the only variables without significant heterogeneity. Evidence is based on prospective or retrospective case series without control group or any active comparison. Fortunately, most studies share common criteria to evaluate effectiveness; however, we have verified that there is high heterogeneity between studies, at least partly due to the varied composition of the patients in each series, probably reflecting unequal clinical scenarios and different severity of sphincter damage treated. Despite the existing limitations, the information presented in this meta-analysis is still of great interest.

The criteria for the selection of best patients with SUI to be treated with ATOMS and/or AUS are currently a subject of debate and the decision to use ATOMS is influenced by medical and patient preference biases [8–10]. A good selection for one or other device may improve the results of both. Criteria to define best patient profile can be based on SUI magnitude, former irradiation, patient age, autonomy and manual dexterity. ATOMS can be used both in patients with severe or mild-to-moderate urine loss, but results achieved in the series with a mean pad count of less than 6 PPD are significantly better. However, the magnitude of improvement (differential pad count and 24-h pad test) is even higher in the series with greater SUI severity, and that could explain a high satisfaction rate even in those reports [8, 12]. Besides, we confirm that studies on ATOMS with a large proportion of previous irradiation achieve worse dryness rates than the rest, but almost the same improvement rate and paradoxically higher differential pad count. That could sustain an opinion that ATOMS may be an optimal choice in irradiated patients, also for diminished risk of complications such as urethral atrophy or erosion [15]. However, a recent series with predominance of SSP confirmed that both radiation and SUI severity are independent risk factors for ATOMS failure [12], but these risk factors also determine worse results both for retrobulbar male slings [5, 32] and for AUS [6, 33].The use of the latest generation device with SSP also reveals better dry rates than reports with devices of predominantly previous generations, but contrary to previous belief [12], not a significant lower risk for complications. However, this difference could also result from a learning curve effect and better patient selection in more recently treated patients. The option to perform office-based postoperative adjustment with ATOMS compared to other adjustable slings that need re-intervention, such as Male Reemex System® (Neomedic International, Tarrasa, Spain) or Argus® (Promedon, Buenos Aires, Argentina), is another aspect to be considered [1, 7].

In the light of this meta-analysis, AUS can no longer be considered the only surgical option to treat severe male SUI. Randomized comparative studies between ATOMS and AUS should be undertaken to shed light on best patient selection for one or other device. Also, ATOMS use in special populations should be better explored. All series include some degree of patients not previously undergoing prostatectomy, but only in two studies was ATOMS evaluated exclusively after TURP [25, 27]. Both studies present limited numbers of patients, but in general terms effectiveness results are comparable to those of SUI after prostatectomy. In addition, another very interesting population is patients after previously failed anti-incontinence devices (i.e. male sling, AUS or even previous ATOMS). Thirteen studies included some of these patients, but only a recent report exclusively evaluated the effectiveness of ATOMS as a second-line treatment after the failure of other surgical devices, showing similar rates of continence and satisfaction as first-line treatment [28].

Global safety of the ATOMS device is also attractive as most studies hardly describe major complications. The most common postoperative side effect is transient perineal-scrotal dysesthesia, usually controlled with non-opioid analgesics until it disappears within the first months. Most published series lack urethral erosion because neither bulbo-spongiosus muscle is dissected, nor does ATOMS apply a circumferential compression on the urethra. For this reason, ATOMS is of paramount indication in the fragile urethra, and is attractive after explantation of other previous failed devices. Low explantation rates can be explained by the silicone coverage of SSP, a single incision surgery (opposed to a double incision for AUS), a reduced time of surgery and a simple surgical procedure associated with a short learning curve. In addition, most authors agree that infections could be reduced with meticulous perioperative care and a preoperative negative urine culture [8, 12, 20].

The main limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis lie in the scant level of evidence provided by the design and nature of the non-controlled, and mainly retrospective, studies available, and in their relatively short follow-up. The variable nature and severity of SUI and the different proportion of patients receiving radiation likely explain the high heterogeneity observed. Combining the results of individual studies increases the total number of participants and more participants imply more statistical power. However, combining studies with differences among participants can also reduce statistical power and make real effects more difficult to identify [34].

Conclusion

According to the current evidence, the ATOMS system for the treatment of male SUI after prostate surgery appears to be an efficacious and safe procedure, with pooled data showing high objective effectiveness and low rate of complications in the short and medium term. The most important contribution of this meta-analysis is not only a single statistical summary of effect size but also the ability to elucidate why different studies have produced different results. We consider it would be of great interest to develop comparative prospective studies in the future among ATOMS and other devices, not only regarding effectiveness but also including patient-reported outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge David Lora and Juan Francisco Dorado (Pertica) for statistical analysis.

Funding

No source of funding was received for the study and publication.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for ths version to be published.

Disclosures

Cristina Esquinas and Javier Angulo declare that they have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and is not itself a study with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7387733.

References

- 1.Kretschmer A, Hübner W, Sandhu JS, Bauer RM. Evaluation and management of postprostatectomy incontinence: a systematic review of current literature. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2:245–59. 10.1016/j.euf.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. EAU guidelines on the assessment of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1099–109. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montague DK. Artificial urinary sphincter: long-term results and patient satisfaction. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:835290. 10.1155/2012/835290. 10.1155/2012/835290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Aa F, Drake MJ, Kasyan GR, Petrolekas A, Cornu JN, Young Academic Urologists Functional Urology Group. The artificial urinary sphincter after a quarter of a century: a critical systematic review of its use in male non-neurogenic incontinence. Eur Urol. 2013;63:681–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahai A, Abrams P, Dmochowski R, Anding R. The role of male slings in post prostatectomy incontinence: ICI-RS 2015. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:927–34. 10.1002/nau.23264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radadia KD, Farber NJ, Shinder B, Polotti CF, Milas LJ, Tunuguntla HSGR. Management of postradical prostatectomy urinary incontinence: a review. Urology. 2018;113:13–9. 10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung E. Contemporary surgical devices for male stress urinary incontinence: a review of technological advances in current continence surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(Suppl 2):S112–21. 10.21037/tau.2017.04.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angulo J, Arance I, Esquinas C, Dorado J, Marcelino J, Martins F. Outcome measures of adjustable transobturator male system with pre-attached scrotal port for male stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1173–83. 10.1007/s12325-017-0528-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esquinas C, Arance I, Pamplona J, Moraga A, Dorado JF, Angulo JC. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence after prostatectomy with the adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS®) with preattached scrotal port. Actas Urol Esp. 2018;42:473–82. 10.1016/j.acuro.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comiter CV, Dobberfuhl AD. The artificial urinary sphincter and male sling for postprostatectomy incontinence: which patient should get which procedure? Investig Clin Urol. 2016;57:3–13. 10.4111/icu.2016.57.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer W, Brössner C. Adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS) for the treatment of post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: the surgical technique. Pelviperineology. 2011;30:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angulo JC, Cruz F, Esquinas C, et al. Treatment of male stress urinary incontinence with the adjustable transobturator male system: outcomes of a multi-center Iberian study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:1458–66. 10.1002/nau.23474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoda MR, Primus G, Schumann A, et al. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: adjustable transobturator male system—results of a multicenter prospective observational study. Urologe A. 2012;51:1576–83 (Article in German). 10.1007/s00120-012-2950-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seweryn J, Bauer W, Ponholzer A, Schramek P. Initial experience and results with a new adjustable transobturator male system for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2012;187:956–61. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoda MR, Primus G, Fischereder K, et al. Early results of a European multicentre experience with a new self-anchoring adjustable transobturator system for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in men. BJU Int. 2013;111:296–303. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11482.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause J, Tietze S, Behrendt W, Nast J, Hamza A. Reconstructive surgery for male stress urinary incontinence: experiences using the ATOMS® system at a single center. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2014;3:Doc15. 10.3205/iprs000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.González SP, Cansino JR, Portilla MA, Rodriguez SC, Hidalgo L, De la Peña J. First experience with the ATOMS® implant, a new treatment option for male urinary incontinence. Cent Eur J Urol. 2014;67:387–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedl A, Bauer W, Rom M, Kivaranovic D, Lüftenegger W, Brössner C. Sexuality and erectile function after implantation of an adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS) for urinary stress incontinence. A multi-institutional prospective study. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;87:306–11. 10.4081/aiua.2015.4.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mühlstädt S, Friedl A, Mohammed N, et al. Five-year experience with the adjustable transobturator male system for the treatment of male stress urinary incontinence: a single-center evaluation. World J Urol. 2017;35:145–51. 10.1007/s00345-016-1839-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedl A, Mühlstädt S, Rom M, et al. Risk factors for treatment failure with the adjustable transobturator male system incontinence device: who will succeed, who will fail? Results of a multicenter study. Urology. 2016;90:189–94. 10.1016/j.urology.2015.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Badry MS, El Hefnawy AS, Gabr AH, Hammady AR. Use of the adjustable trans-obturator male sling system for the treatment of male incontinence. An initial experience. Afr J Urol. 2016;22:127–30. 10.1016/j.afju.2015.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hüsch T, Kretschmer A, Thomsen F, et al. Risk factors for failure of male slings and artificial urinary sphincters: Results from a large middle European cohort study. Urol Int. 2017;99:14–21 (Debates on Male Incontinence (DOMINO)-Project). 10.1159/000449232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buresova E, Vidlar A, Grepl M, Student Jr V, Student V. Single-centre experience in using the adjustable transobturator male system in treatment of stress urinary incontinence in patients after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Urol. 10.1177/2051415817701054.

- 24.Friedl A, Mühlstädt S, Zachoval R, et al. Long-term outcome of the adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS): results of a European multicentre study. BJU Int. 2017;119:785–92. 10.1111/bju.13684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedl A, Schneeweiss J, Stangl K, et al. The adjustable transobturator male system in stress urinary incontinence after transurethral resection of the prostate. Urology. 2017;109:184–9. 10.1016/j.urology.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manso M, Alexandre B, Antunes-Lopes T, Martins-da-Silva C, Cruz F. Is the adjustable transobturator system ATOMS® useful for the treatment of male urinary incontinence in low to medium volume urological centers? Actas Urol Esp. 2018;42:267–72. 10.1016/j.acuro.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angulo JC, Fonseca J, Esquinas C, et al. Adjustable transobturator male system (ATOMS®) as treatment of stress urinary incontinence secondary to transurethral resection of the prostate. Actas Urol Esp. 2018. 10.1016/j.acuro.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Angulo JC, Esquinas C, Arance I, et al. Adjustable transobturator male system after failed surgical devices for male stress urinary incontinence: a feasibility study. Urol Int. 2018;101:106–13. 10.1159/000489316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzer G. Meta: an R package for meta-analysis. R New. 2007;7:40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna; 2016. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 32.Habashy D, Losco G, Tse V, Collins R, Chan L. Mid-term outcomes of a male retro-urethral, transobturator synthetic sling for treatment of post-prostatectomy incontinence: impact of radiotherapy and storage dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:1147–50. 10.1002/nau.23078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivera ME, Linder BJ, Ziegelmann MJ, Viers BR, Rangel LJ, Elliott DS. The impact of prior radiation therapy on artificial urinary sphincter device survival. J Urol. 2016;195:1033–7. 10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnard ND, Willett WC, Ding EL. The misuse of meta-analysis in nutrition research. JAMA. 2017;318:1435–6. 10.1001/jama.2017.12083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.