Abstract

Introduction

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) cause significant impairment in quality of life. Although they share similar genetic factors, environmental precipitants, and pathophysiological mechanisms, there is little evidence on the risk of developing subsequent IMIDs after an initial IMID diagnosis. We sought to assess the risk of developing subsequent IMIDs among patients diagnosed with an initial IMID.

Methods

This retrospective matched cohort study used a large US commercial health insurance claims database (01/01/2006–09/30/2015). The risks of developing secondary IMIDs among patients aged 18–64 years with a diagnosis of one of nine IMIDs of interest (ankylosing spondylitis, celiac disease, hidradenitis suppurativa [HS], inflammatory bowel disease, lupus, psoriatic arthritis [PsA], psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis) as identified from diagnosis codes on medical claims were compared with up to 1000 matched controls without the primary IMID using Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Across the nine IMIDs of interest, there were 398,935 unique case patients matched to 256,795,796 non-unique control patients. Case patients with an initial IMID had higher risks of developing each, any one, and any two of the other eight secondary IMIDs compared to their matched controls. Hazard ratios [95% confidence intervals] for the risk of developing any one secondary IMID ranged from 5.4 [5.0, 5.8] (initial IMID: HS) to 62.2 [59.9, 64.6] (initial IMID: PsA), and hazard ratios for developing any two secondary IMIDs ranged from 3.0 [2.3, 3.8] (HS) to 75.2 [69.3, 81.7] (PsA).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the risk of developing a second IMID is significantly higher for individuals who have already experienced a first IMID in a large and contemporary US claims database. Certain pairs of IMIDs co-occur more frequently than others. The risk of developing subsequent IMIDs may be an important consideration for clinicians when selecting treatment strategies.

Funding

Abbvie.

Electronic Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-019-00964-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Claims data, Epidemiology, Immune-mediated inflammatory disease, Rheumatology

Introduction

Immune-mediated inflammatory disease (IMID) describes a class of conditions that share common inflammatory pathways. Previously called autoimmune disorders, there are more than 80 different disorders in this class, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease [1–3]. These diseases share similar genetic factors, environmental triggers, and pathophysiological mechanisms, a phenomenon known as autoimmune tautology [2, 4]. Polyautoimmunity, the presence of two or more IMIDs in a single patient, supports the autoimmune tautology theory and has been reported previously in the literature; it implies that patients with an existing IMID may be at higher risk of developing additional IMIDs [2, 5, 6].

Although prior studies have examined the risk of subsequent IMIDs in patients with an existing IMID, they are limited in scope and scale because of low IMID incidence rates and data limitations [3, 5, 7–10]. Published studies demonstrate that many IMIDs are relatively rare, with the combined prevalence of a group of 29 IMIDs estimated to be 7.6–9.4% [6]. Large, real-world data sources can allow for investigation of occurrence patterns, comorbid illnesses, and coexistence of relatively rare conditions. Further, as treatments are currently available or in development for several IMIDs, clinicians may incorporate knowledge of the risks of secondary IMIDs into their treatment decisions and preventive care strategies for patients with existing IMIDs. To better understand the interrelation of IMIDs and frequency of subsequent IMID development, we assessed the risk of secondary IMID development among patients with an existing IMID in a large claims database of commercially insured adults in the USA.

Methods

Study Design

The association between having one of nine initial IMIDs and the risk of subsequently developing one or more of the other eight IMIDs was assessed using a large administrative database of commercial insurance claims from 2006 through 2015. Secondary IMID incidence was compared between cohorts of patients with each initial IMID and their matched controls using stratified Cox proportional hazards models.

Data Source

This retrospective, matched cohort study used data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database from January 1, 2006 through September 30, 2015. The MarketScan patient-level administrative database contains insurance enrollment and medical and pharmacy claims from health insurers and self-insured employers across the USA. It includes longitudinal information on patient demographics and clinical diagnoses recorded using International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes. This study used de-identified which complied with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and was therefore deemed to not constitute Human Subjects Research nor require IRB approval.

IMID Selection

The nine IMIDs selected for this study were ankylosing spondylitis (AS), celiac disease (CE), hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), lupus (LU), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), psoriasis (PsO), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and uveitis (UV). These IMIDs were selected because they are identifiable in claims data using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and have medications available or in development for their treatment. The ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes used to identify these conditions are listed in Table S1.

Study Population

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were between 18 and 64 years old at their index date (defined below); had at least 365 days of continuous enrollment both before and after their index date; and had valid values for sex, insurance type, and location of residence in the USA (50 states or Washington, DC). Patients aged 65 years and older at their index date were excluded as the majority of these patients receive health insurance coverage under Medicare and subsequently have health claims that are unobservable in the MarketScan database. For individuals with interruptions in their insurance enrollment resulting in multiple enrollment periods lasting 730 days or more, one enrollment period was selected at random.

Case and Control Selection

Separate cohorts were created for each of the nine selected IMIDs. For each IMID cohort, cases consisted of patients with a positive diagnosis of an IMID that was based on the presence of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes on at least two medical claims that were 30 days or more apart and that occurred at least 365 days after the patient’s entry into the data [11, 12]. For patients with initial claims for multiple IMIDs of interest, the IMID with the earliest second claim was designated as the initial IMID. The date of the first diagnosis for the initial IMID was assigned as the index date for case patients.

To reduce the computational burden for identification of control patients, a simple random sample of 5 million control candidates was selected from the overall MarketScan database population of 37 million individuals [13]. From this sample, up to 1000 control patients were matched with replacement to each case patient on sex, age (± 1 year), insurance plan type, and state of residence (Fig. S1). When more than 1000 control patients matched, 1000 were selected at random. Candidate controls were assigned the index date of their matched case patient. Candidate controls were excluded if they had any claim for the case’s initial IMID prior to the index date or if their first IMID claim after the index date was for the case’s initial IMID (e.g., for AS case patients, the first IMID a control patient developed after the index date had to be different from AS).

Outcomes

For each matched IMID cohort, the primary outcomes were the development of each, any one, and any two of the other eight secondary IMIDs after the index date through September 30, 2015. The risk of a case patient developing a secondary IMID was measured on the basis of the presence of at least one claim with a diagnosis for the secondary IMID after the index date. Control patients were excluded from risk calculations for a given secondary IMID if their first claim for the secondary IMID occurred prior to the index date. Controls with a diagnosis for one of the other seven secondary IMIDs, however, were included in the analysis of that secondary IMID regardless of when the diagnosis was first recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the covariates used to match control patients to case patients (i.e., patient sex, age, insurance plan type, and state of residence) were calculated for case patients combined across the nine IMIDs. To assess covariate balance after matching, baseline characteristics were compared between case and matched control patients for each initial IMID by calculating stratified standardized differences [14, 15].

The crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years of developing each, any one, and any two of eight secondary IMIDs were calculated for case and matched control patients separately according to the initial IMID. The risk of developing each secondary IMID for case patients compared with their matched controls was assessed using stratified, continuous-time Cox proportional hazards models to account for differences in follow-up time. Model results are presented as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI), where the hazard ratio represents the ratio of the instantaneous risk of developing a secondary IMID among case patients to the analogous risk for controls. Models were stratified to account for IMID-specific match groups, each of which consisted of a case patient and their matched controls. Model standard errors were adjusted to account for the clustering of patients into match groups.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). P values less than 0.05 from two-sided hypothesis tests were considered statistically significant.

Sensitivity Analyses

In the main analysis, secondary IMIDs were identified by the presence of a single medical claim, which is maximally sensitive but may result in misdiagnosis. To increase the specificity of diagnosis, analyses were repeated after requiring secondary IMIDs to appear on at least two medical claims.

Clinical misdiagnosis of the initial IMID may artificially inflate associations between initial and secondary IMIDs as identified in claims if the secondary IMID diagnosis is intended to replace (rather than add to) the initial IMID diagnosis. To address this, analyses were repeated for the three included musculoskeletal IMIDs (AS, PsA, and RA), which have a higher risk of misdiagnosis. Case patients with AS, PsA, or RA as their initial IMID and one of the other two conditions as their secondary IMID were required to have one or more additional claim for the initial IMID after the first claim for the secondary IMID, thereby providing evidence that the diagnosis for the initial IMID persisted even after the diagnosis of the secondary IMID was made. Outcomes for control patients were unchanged from their original definitions.

Results

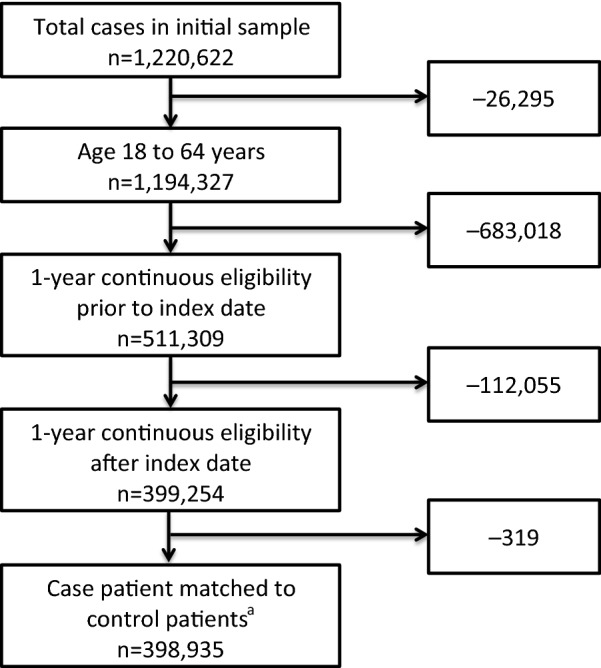

There were 1,220,622 unique individuals with an initial IMID eligible to be in a case cohort (Fig. 1). Across the nine IMIDs of interest, there were 398,935 unique case patients matched to 256,795,796 non-unique control patients after the sample selection criteria were applied. The final number of case patients ranged from 6352 for AS to 115,141 for PsO, and for matched control patients from 4,059,296 for AS to 74,228,131 for PsO. Among case patients, the mean age at earliest initial IMID claim was 46.5 years, 63.3% were female, 61.9% were covered by a preferred provider organization plan, and 40.0% resided in the South Census region (Table 1). Demographic characteristics stratified by initial IMID case cohort were largely similar, with the exception of sex (Table S2). The observed period of continuous enrollment without the IMID of interest prior to a case patient’s first primary IMID diagnosis date was between 1 and 2 years for 39% of the sample, 2–3 years for 19%, 3–4 years for 12%, and more than 4 years for 30%. The mean number of matched control patients per case patients ranged from 598 for HS to 668 for RA. Median follow-up time was slightly longer in case patients (range 918–1023 days) than control patients (range 883–971 days).

Fig. 1.

Cohort selection criteria for case patients. aCase patients were matched to at least one control patient on the basis of age (± 1 year), sex, insurance plan type, state of residence, and 1 year or more of continuous eligibility before and after the case patient’s index date

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for case patients with one of nine initial IMIDs

| Variable name | Cases (n = 398,935) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 46.5 (11.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (17) |

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Male | 146,505 (36.7) |

| Female | 252,430 (63.3) |

| Plan type, N (%) | |

| Comprehensive | 19,516 (4.9) |

| Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO) | 5001 (1.3) |

| Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) | 65,134 (16.3) |

| Point of Service (POS) | 38,534 (9.7) |

| Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) | 246,763 (61.9) |

| POS w/capitation | 7344 (1.8) |

| Consumer-Directed Health Plan (CDHP) | 10,773 (2.7) |

| High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) | 5870 (1.5) |

| Census region, N (%) | |

| Northeast | 70,209 (17.6) |

| Midwest | 94,331 (23.6) |

| South | 159,702 (40.0) |

| West | 74,693 (18.7) |

| Index year, N (%) | |

| 2007 | 32,041 (8.0) |

| 2008 | 48,076 (12.1) |

| 2009 | 47,172 (11.8) |

| 2010 | 53,834 (13.5) |

| 2011 | 72,623 (18.2) |

| 2012 | 58,927 (14.8) |

| 2013 | 53,432 (13.4) |

| 2014 | 32,830 (8.2) |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

Covariate balance between case and matched control patients was assessed before and after stratification by match group. Before stratification, mean differences in covariates were small (1–5% for categorical variables and 1 year for patient age). After stratification, mean case–control differences were 0 for the covariates on which exact matching occurred (patient sex, insurance plan type, state of residence) and for year of index date. The mean difference in age was reduced to approximately 0.01 years after stratification.

Overall, secondary IMIDs occurred more frequently among case patients with an initial IMID than controls (Table 2). Across initial IMID cohorts, the range of incidence rates (events per 1000 person-years) for development of any one secondary IMID was 17.6 (initial IMID: HS) to 234.1 (PsA) for case patients compared with 2.6 to 3.7 for controls. Likewise, incidence rates for development of any two secondary IMIDs ranged from 1.4 (HS) to 32.6 (PsA) for case patients and 0.4 to 0.5 across the nine initial IMIDs for controls.

Table 2.

Secondary IMID conditional incidence rates per 1000 person-years for case and control patients

| Initial IMID | Secondary IMIDa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AS | CE | HS | LU | PsA | PsO | RA | UV | IBD | Any 1 | Any 2 | |

| Case patients | ||||||||||||

| AS | 6352 | – | 2.1 | 0.4 | 7.2 | 11.3 | 9.0 | 64.4 | 17.4 | 8.4 | 105.2 | 14.6 |

| CE | 19,217 | 0.4 | – | 0.7 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 10.0 | 28.2 | 2.2 |

| HS | 14,136 | 0.4 | 0.9 | – | 1.7 | 0.5 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 17.6 | 1.4 |

| LU | 29,690 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 1.3 | – | 2.0 | 5.3 | 59.6 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 71.9 | 5.2 |

| PsA | 8406 | 6.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 5.3 | – | 173.1 | 109.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 234.1 | 32.6 |

| PsO | 115,141 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 22.1 | – | 8.8 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 33.4 | 5.3 |

| RA | 103,036 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 18.4 | 8.9 | 7.4 | – | 3.2 | 4.0 | 46.3 | 5.2 |

| UV | 34,422 | 7.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 13.9 | – | 4.7 | 32.7 | 4.5 |

| IBD | 68,535 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 8.5 | 3.5 | – | 23.1 | 2.1 |

| Control patients | ||||||||||||

| AS | 4,059,296 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 0.4 |

| CE | 11,520,448 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 0.5 |

| HS | 8,447,796 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 0.5 |

| LU | 19,812,412 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 0.5 |

| PsA | 5,380,715 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 0.5 |

| PsO | 74,228,131 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 0.4 |

| RA | 68,808,782 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.4 |

| UV | 22,166,447 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 0.5 |

| IBD | 42,371,769 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.5 |

Conditional incidence rates reflect the likelihood of developing a secondary IMID conditional on being in the sample for the initial IMID

aSecondary IMIDs were identified by presence of at least one claim with an ICD-9 diagnosis code for that secondary IMID

Relative to their matched controls, case patients with an initial IMID had higher risks of developing each, any one, and any two of the other eight secondary IMIDs (Table 3). Across the initial IMIDs, hazard ratios [95% CI] for the risk of developing any one secondary IMID ranged from 5.4 [5.0, 5.8] for patients with HS to 62.2 [59.9, 64.6] for patients with PsA. The hazard ratio [95% CI] for developing any two secondary IMIDs was also smallest for HS patients (3.0 [2.3, 3.8]) and largest for PsA patients (75.2 [69.3, 81.7]).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios [95% CI] for the risk of developing secondary IMIDs

| Initial IMID | Secondary IMIDa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AS | CE | HS | LU | PsA | PsO | RA | UV | IBD | Any 1 | Any 2 | |

| AS | 4,065,648 | – | 11.2 | 3.3 | 23.7 | 50.8 | 8.6 | 63.2 | 54.9 | 16.0 | 31.4 | 35.7 |

| [–, –] | [8.0, 15.5] | [1.5, 7.0] | [19.8, 28.3] | [43.7, 59.0] | [7.4, 10.1] | [58.6, 68.2] | [48.5, 62.3] | [13.5, 19.0] | [29.7, 33.1] | [31.2, 40.7] | ||

| CE | 11,539,665 | 4.0 | – | 4.0 | 8.7 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 17.6 | 7.8 | 4.5 |

| [2.7, 6.2] | [–, –] | [2.9, 5.6] | [7.5, 10.0] | [2.0, 3.8] | [4.8, 6.0] | [5.4, 6.6] | [4.3, 6.4] | [16.0, 19.3] | [7.4, 8.3] | [3.8, 5.4] | ||

| HS | 8,461,932 | 4.4 | 3.2 | – | 4.1 | 2.7 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 3.0 |

| [2.7, 7.1] | [2.3, 4.6] | [–, –] | [3.2, 5.2] | [1.8, 4.1] | [5.9, 7.6] | [4.0, 5.3] | [4.2, 6.8] | [4.7, 6.7] | [5.0, 5.8] | [2.3, 3.8] | ||

| LU | 19,842,102 | 15.5 | 11.5 | 7.5 | – | 7.8 | 5.1 | 41.8 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 18.9 | 10.0 |

| [13.1, 18.3] | [10.1, 13.1] | [6.1, 9.1] | [–, –] | [6.7, 9.1] | [4.6, 5.5] | [40.5, 43.2] | [8.7, 10.8] | [6.3, 7.8] | [18.4, 19.4] | [9.1, 11.0] | ||

| PsA | 5,389,121 | 71.4 | 5.3 | 10.5 | 14.1 | – | 163.2 | 91.5 | 10.0 | 7.3 | 62.2 | 75.2 |

| [60.2, 84.6] | [3.6, 7.7] | [7.3, 15.1] | [11.8, 16.8] | [–, –] | [155.0, 171.9] | [86.4, 96.9] | [8.1, 12.2] | [5.9, 8.9] | [59.9, 64.6] | [69.3, 81.7] | ||

| PsO | 74,343,272 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 197.3 | – | 7.9 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 13.0 | 14.3 |

| [5.1, 6.7] | [5.0, 6.1] | [7.7, 9.4] | [4.3, 5.1] | [191.8, 203.0] | [–, –] | [7.6, 8.2] | [4.1, 4.8] | [3.9, 4.4] | [12.7, 13.2] | [13.7, 15.0] | ||

| RA | 68,911,818 | 78.5 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 55.3 | 46.9 | 7.2 | – | 8.2 | 7.6 | 16.8 | 14.0 |

| [74.1, 83.1] | [9.5, 11.1] | [7.2, 9.1] | [53.7, 57.0] | [45.0, 48.9] | [6.9, 7.5] | [–, –] | [7.7, 8.8] | [7.2, 8.0] | [16.5, 17.1] | [13.3, 14.7] | ||

| UV | 22,200,869 | 89.3 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 11.1 | – | 8.7 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| [82.6, 96.7] | [3.9, 5.8] | [5.6, 8.6] | [7.7, 9.5] | [4.6, 6.4] | [3.8, 4.6] | [10.6, 11.8] | [–, –] | [8.0, 9.6] | [9.3, 9.9] | [8.7, 10.5] | ||

| IBD | 42,440,304 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 8.0 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 7.4 | 10.2 | – | 7.5 | 4.6 |

| [11.8, 15.3] | [13.9, 16.4] | [7.0, 9.1] | [5.1, 6.1] | [1.9, 2.8] | [4.7, 5.3] | [7.1, 7.8] | [9.5, 11.0] | [–, –] | [7.3, 7.8] | [4.2, 5.1] | ||

Hazard of developing a secondary IMID condition for case patients relative to control patients conditional on being in the initial IMID condition sample. Ratios above 1 indicate a higher risk for case patients than control patients

aSecondary IMIDs were identified by presence of at least one claim with an ICD-9 diagnosis code for that secondary IMID

Findings from the sensitivity analyses were largely consistent with the base case results. When requiring two or more claims for a positive secondary IMID diagnosis, the magnitudes of the estimated incidence rates and hazard ratios were substantially attenuated, with most reduced by approximately half (Tables S3 and 4). Relative to controls, case patients had a statistically significantly greater risk of developing a secondary IMID for all but six IMID pairs (out of 81 estimated hazard ratios in all). The second sensitivity analysis, which examined potential misdiagnosis among the three musculoskeletal IMIDs, similarly found that incidence rates for case patients and hazard ratios were smaller than estimated in the main analyses, but that individuals with an initial IMID of AS, PsA, or RA had a substantially increased risk of developing either of the other two IMIDs than did control patients regardless of whether at least one or at least two claims were required for a positive secondary IMID diagnosis (Table S4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis 1: Hazard ratios [95% CI] for the risk of developing secondary IMIDs

| Initial IMID | Secondary IMIDa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AS | CE | HS | LU | PsA | PsO | RA | UV | IBD | Any 1 | Any 2 | |

| AS | 4,065,648 | – | 4.0 | 0.4 | 7.9 | 38.2 | 3.7 | 30.9 | 31.8 | 9.2 | 15.1 | 25.3 |

| [–, –] | [2.3, 7.0] | [0.1, 3.4] | [5.7, 11.1] | [31.2, 46.7] | [2.9, 4.7] | [27.9, 34.3] | [26.9, 37.6] | [7.3, 11.6] | [14.0, 16.2] | [20.1, 32.0] | ||

| CE | 11,539,665 | 2.3 | – | 0.6 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| [1.2, 4.4] | [–, –] | [0.2, 1.4] | [3.1, 5.0] | [0.6, 2.0] | [1.5, 2.3] | [2.3, 3.2] | [1.1, 2.4] | [4.7, 6.4] | [2.5, 3.0] | [1.8, 3.7] | ||

| HS | 8,461,932 | 3.5 | 0.6 | – | 1.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| [1.8, 6.7] | [0.3, 1.3] | [–, –] | [0.7, 1.8] | [1.3, 3.9] | [1.9, 2.9] | [1.6, 2.5] | [1.1, 2.7] | [1.5, 2.7] | [1.7, 2.1] | [1.0, 2.7] | ||

| LU | 19,842,102 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 2.1 | – | 4.1 | 2.1 | 19.6 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 8.1 | 5.5 |

| [5.4, 9.5] | [3.3, 5.2] | [1.5, 3.1] | [–, –] | [3.3, 5.2] | [1.8, 2.4] | [18.7, 20.5] | [2.8, 4.1] | [1.6, 2.4] | [7.8, 8.4] | [4.5, 6.6] | ||

| PsA | 5,389,121 | 42.6 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 4.9 | – | 94.1 | 48.4 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 33.4 | 58.3 |

| [33.2, 54.6] | [0.8, 3.3] | [1.8, 7.0] | [3.5, 6.8] | [–, –] | [88.4, 100.2] | [45.0, 52.1] | [2.9, 5.6] | [2.1, 4.1] | [31.8, 35.0] | [50.7, 66.9] | ||

| PsO | 74,343,272 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 144.6 | – | 3.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 6.7 | 12.9 |

| [2.6, 4.0] | [1.6, 2.2] | [1.9, 2.8] | [1.5, 2.0] | [139.6, 149.9] | [–, –] | [3.1, 3.5] | [1.2, 1.7] | [1.2, 1.6] | [6.6, 6.9] | [12.0, 14.0] | ||

| RA | 68,911,818 | 47.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 26.7 | 41.2 | 3.4 | – | 2.9 | 2.8 | 8.1 | 12.0 |

| [43.7, 51.2] | [2.6, 3.4] | [1.8, 2.8] | [25.6, 27.8] | [39.1, 43.3] | [3.2, 3.6] | [–, –] | [2.6, 3.2] | [2.5, 3.0] | [7.9, 8.3] | [11.0, 13.0] | ||

| UV | 22,200,869 | 68.1 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 4.7 | – | 5.0 | 4.5 | 7.6 |

| [61.4, 75.5] | [1.1, 2.2] | [1.3, 2.9] | [2.8, 4.1] | [3.9, 6.0] | [1.3, 1.8] | [4.3, 5.1] | [–, –] | [4.4, 5.6] | [4.3, 4.7] | [6.5, 8.9] | ||

| IBD | 42,440,304 | 9.7 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 4.2 | – | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| [8.1, 11.5] | [3.9, 5.3] | [2.2, 3.4] | [2.2, 3.0] | [1.3, 2.1] | [1.8, 2.2] | [3.3, 3.8] | [3.7, 4.7] | [–, –] | [2.9, 3.2] | [2.5, 3.5] | ||

Hazard of developing a secondary IMID condition for case patients relative to control patients conditional on being in the initial IMID condition sample. Ratios above 1 indicate a higher risk for case patients than control patients

aSecondary IMIDs were identified by presence of two or more claims at least 30 days apart with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for that secondary IMID

Discussion

This claims data analysis demonstrated that patients with any one of nine IMIDs had statistically significantly higher risk of developing a subsequent IMID. The hazard ratio for developing any one of the eight secondary IMIDs ranged from 5.4 for patients with HS to 62.2 for patients with PsA, while the hazard ratio for developing any two secondary IMIDs ranged from 3.0 (HS) to 75.2 (PsA). Results were attenuated only moderately in sensitivity analyses that used stricter definitions for identifying secondary IMIDs (Table 4).

Although previous analyses have used large epidemiological and insurance claims databases to assess IMID co-occurrence, comparisons with this study are difficult because of differences in IMID selection and statistical methodology. Using data from the Nurses’ Health Study, Li et al. found that patients with PsO had a significantly higher risk of developing Crohn’s disease, but not ulcerative colitis, compared to patients without PsO [10]. When including both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the definition of IBD, we found that PsO patients had a higher risk of developing IBD than did matched controls. Weng et al. reported that patients enrolled in a US managed care organization with IBD had significantly higher odds of also having PsO (odds ratio [OR] 1.7) and RA (OR 1.9) compared to matched controls [7]. In two different commercial claims databases from the USA, Cohen et al. found that IBD patients had significantly higher odds of having AS (OR 5.8 and 7.8) and RA (OR 2.1 and 2.7) [8].

Several possible mechanisms may explain the associations observed in our study and in previous research, only some of which are understood. The high observed concordance between some IMID pairs may be attributable in part to diagnostic uncertainty that results from overlapping, non-specific symptomatology between those pairs. However, in sensitivity analyses attempting to account for this uncertainty among three musculoskeletal IMIDs that have a greater potential for misdiagnosis (AS, PsA, and RA), the risk of developing the secondary IMIDs remained markedly increased. This may indicate that an existing diagnosis of a musculoskeletal IMID—at least as identified in insurance claims data—is often not abandoned when a clinically related IMID is newly diagnosed.

Other IMIDs are known to co-occur frequently. For example, PsA may occur in up to one-third of patients with diagnosed PsO [16]. Where clinical manifestations of IMIDs have an apparent epidemiologic co-occurrence, they may be considered to belong to the same class of disease, such as in the spondylarthropathies, which are associated with manifestations of AS, UV, PsO, PsA, and IBD [17–19]. The exact etiology of several IMID co-occurrences observed in this study is unknown, though it has been hypothesized that IMIDs share common genetic origins that may increase patients’ susceptibility to development of multiple, apparently unrelated IMIDs [2, 5, 20].

Although the analytic focus of this study was pairwise associations between individual IMIDs, identifying clusters of at least three IMIDs, termed multiple autoimmune syndrome (MAS) [20], may offer additional clues to the drivers connecting IMIDs. MAS was explored in this study by assessing the risk of developing two additional IMIDs for patients with an initial IMID versus their matched controls. All nine primary IMIDs were associated with a statistically significantly increased risk of MAS, but the magnitude of the risk varied across primary IMIDs. The largest increased risk occurred in patients initially diagnosed with PsA, which has a particularly strong association with PsO. Patients initially diagnosed with AS had the second-highest risk, followed by patients first diagnosed with PsA and RA.

Our results suggest paths for future research and have potential implications for clinical practice. The markedly higher risks observed for development of certain secondary IMIDs call for an increased level of clinical alertness in patients diagnosed with the corresponding initial IMID. As many of the IMIDs assessed in this study have the potential to permanently affect physical integrity or organ function over time, knowledge of their relationships with one another may lead to more timely preventative care and better interdisciplinary, holistic patient management. Further, the role of treatment, particularly those that impact the pathophysiologic pathways associated with IMID development, in IMID co-occurrence is unknown and deserves further study. Knowledge of a treatment’s downstream influence on secondary IMID development may help clinicians’ treatment planning for patients at high risk of developing multiple IMIDs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, while administrative claims data offer a large sample of patients, these data have several weaknesses related to their clinical detail and accuracy. Claims data limit the ability to distinguish among diagnostic uncertainty, a new manifestation of an existing disease (e.g., PsA in patients with PsO), and the genuine onset of a new IMID. It is thus not possible to validate the presence and timing of IMID onset in claims data alone. Nevertheless, results were directionally robust to identifying secondary IMID onset from the presence of at least one or at least two medical claims, and the use of at least two claims has been validated specifically for IBD [12]. In addition, detection of truly incident cases is constrained by the possibility of historical IMID diagnoses made prior to the start of the database’s coverage; thus, some cases presumed to be incident may have been, in fact, prevalent cases [21]. Second, generalizability may be limited because of the scope of IMIDs studied (nine of many autoimmune conditions) and data coverage (our data source reflects the experience of a group of commercially insured, non-elderly individuals in the USA). Third, our analysis was designed to uncover statistical associations between IMIDs, but it cannot reveal the mechanisms driving those relationships. Fourth, our results may be susceptible to detection bias, as case patients may have had more contact with clinicians (and thus more opportunity to be diagnosed with a secondary IMID) than did control patients.

Conclusions

This study extends prior research by demonstrating in a large and contemporary US claims database a significantly higher risk of developing a second IMID for individuals who already experienced one of nine IMIDs. Certain pairs of IMIDs were found to co-occur at a much higher rate than others, though the etiology of some of these relationships remains unclear. The risk of developing subsequent IMIDs may be an important consideration for clinicians when managing patients with other autoimmune conditions and when establishing treatment goals.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, the article processing charges and the Open Access fee were funded by AbbVie Inc. This study was funded by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in data analysis, interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing services were provided by Lufei Tu of Medicus Economics. Medical writing services were funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Daniel Aletaha has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; has received lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and UCB; and has received grants from AbbVie, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Roche. Andrew J. Epstein is an employee of Medicus Economics, which received payment from AbbVie to participate in this research. Martha Skup is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. Patrick Zueger is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. Vishvas Garg is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. Remo Panaccione has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Baxter, BMS, Celgene, Cubist, Eisai, Eli Lily, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Robarts, Salix, Samsung, Schering-Plough, Shire, Centocor, Elan, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB, Pfizer, and Takeda; has served on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Abbott, Aptalis, AstraZeneca, Ferring, Janssen, Merck, Prometheus, Shire, and Takeda; and has received grants from AbbVie, Abbott, Ferring, Janssen, and Takeda.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study used de-identified data which complied with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and was therefore deemed to not constitute Human Subjects Research nor require IRB approval.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial licensing restrictions required by the data provider.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8006324.

References

- 1.Martin L. Autoimmune disorders: causes 2015 (updated May 21, 2017). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000816.htm. Accessed 2 Apr 2019.

- 2.Kuek A, Hazleman BL, Ostor AJ. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) and biologic therapy: a medical revolution. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(978):251–260. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.052688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson D, Jr, Hackett M, Wong J, Kimball AB, Cohen R, Bala M. Co-occurrence and comorbidities in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders: an exploration using US healthcare claims data, 2001-2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(5):989–1000. doi: 10.1185/030079906X104641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardenas-Roldan J, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. How do autoimmune diseases cluster in families? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:73. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somers EC, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Are individuals with an autoimmune disease at higher risk of a second autoimmune disorder? Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(6):749–755. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(3–4):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng X, Liu L, Barcellos LF, Allison JE, Herrinton LJ. Clustering of inflammatory bowel disease with immune mediated diseases among members of a northern California-managed care organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1429–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen R, Robinson D, Jr, Paramore C, Fraeman K, Renahan K, Bala M. Autoimmune disease concomitance among inflammatory bowel disease patients in the United States, 2001-2002. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(6):738–743. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Blanchard JF. The clustering of other chronic inflammatory diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(3):827–836. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li WQ, Han JL, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn’s disease in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1200–1205. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin DT, Mittal M, Davis M, Johnson S, Chao J, Skup M. Impact of a patient support program on patient adherence to adalimumab and direct medical costs in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):859–867. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.16272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Allison JE, Herrinton LJ. Validity of computerized diagnoses, procedures, and drugs for inflammatory bowel disease in a northern California managed care organization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(11):1086–1093. doi: 10.1002/pds.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell M, Swinscow T. Statistics at square one. New York: Wiley; 2011.

- 14.Hansen B, Bowers J. Covariate balance in simple, stratified and clustered comparative studies. Stat Sci. 2008;23(2):219–236. doi: 10.1214/08-STS254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowers J, Fredrickson M, Hansen B. XBALANCE: Stata module to compute standardized differences for stratified comparisons via R. Boston College Department of Economics; 2008.

- 16.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Boonen A. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):65–73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juanola X, Loza Santamaría E, Cordero-Coma M. Description and prevalence of spondyloarthritis in patients with anterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(8):1632–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vander Cruyssen B, Ribbens C, Boonen A, et al. The epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis and the commencement of anti-TNF therapy in daily rheumatology practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(8):1072–1077. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anaya JM, Castiblanco J, Rojas-Villarraga A, et al. The multiple autoimmune syndromes. A clue for the autoimmune tautology. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43(3):256-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Griffiths RI, O’Malley CD, Herbert RJ, Danese MD. Misclassification of incident conditions using claims data: impact of varying the period used to exclude pre-existing disease. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;6(13):32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial licensing restrictions required by the data provider.