Abstract

Unwanted sexual incidents on university campuses pose significant public health and safety risks for students. This study explored survivors’ perspectives on secondary prevention of campus sexual assault and effective strategies for intervention programs for unwanted sexual incidents in university settings. Twenty-seven student survivors of unwanted sexual experiences participated in semi-structured in-depth interviews. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis and a constructionist perspective. The findings were contextualized using the ecological model. Barriers to reporting included concerns about one’s story not being believed, personal minimization of the incident, belief that no action will be taken after reporting, confidentiality concerns, and other perceived costs of reporting. Survivors provided valuable insight on potentially effective prevention and intervention strategies to address the problem of unwanted sexual incidents on university campuses. These findings may be useful for prevention and intervention policies and programs in university settings and for providers who assist survivors of unwanted sexual experiences.

Keywords: Campus, reporting, sexual assault, students

Unwanted sexual incidents on university campuses are a serious public health concern. The scope of the problem is daunting, with national data showing that among US adults with sexual violence experiences, the victimization most often occurs during college ages (18–24 years; Black et al., 2011). In the recent Association of American Universities survey of 150,072 students at 27 universities, nearly 1 in 10 experienced sexual violence (i.e., forced penetration, attempted or completed) by incapacitation or use of physical force (Cantor et al., 2015). The impact of this violence has immediate and long-term impacts on survivors including negative physical, psychological, and social sequelae as well as higher rates of high-risk behaviors including substance abuse (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2015).

Addressing campus sexual assault is complex. A recent CDC report stressed the importance of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention efforts (Dills, Fowler, & Payne, 2016). This is consistent with directives from the 2014 White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, which aimed to strengthen federal enforcement efforts and provided schools with additional tools to help combat sexual assault (The White House, 2014). Specifically, the Task Force recommended regular campus climate surveys to better understand the nature of sexual assault and to develop best practice responses for campus settings (The White House, 2014). Developing responses, however, requires an emphasis on secondary prevention, where the goal is to “detect and treat a problem at the earliest possible stage when disease or impairment already exists” (Anderson & McFarlane, 2010; p. 31) with the theoretical premise that such “treatment” or intervention will prevent serious long-term consequences. Like all prevention efforts, campus sexual assault secondary prevention needs to address individual, relationship, community, and societal influences on behavior (Dills et al., 2016). At the university level, secondary prevention is only possible if someone reports their assault and triggers the implementation of services such as counseling, physical exams and infection testing, and administrative actions to keep students safe. Further, design of appropriate services for sexual assault survivors need an in-depth understanding of the impact of assault and decision-making around disclosing or reporting the event. Barriers to reporting can delay or prevent survivors from accessing services that can help them manage the negative impact of their assault (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000; Foa, Zoellner, & Feeny, 2006; Hassija & Turchik, 2016).

In a review of empirical studies exploring barriers to disclosure of sexual assault and service utilization, students were more likely to disclose informally to friends than to seek any formal services (Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Fisher et al., 2000; Sabina & Yo, 2014). Barriers to service utilization included shame, embarrassment, minimizing the assault, concerns around confidentiality, fear, denial, and belief that existing services for survivors would not help (Sabina & Yo, 2014; Sable, Danis, Mauzy, & Gallagher, 2006; Zinzow & Thompson, 2011). Few of the studies included firsthand accounts from survivors or represented the diversity of race, gender identities, and sexual orientation increasingly common in many university campuses today. We did not find any studies that addressed the range of barriers unique to university settings from qualitative in-depth interviews. Identifying barriers can assist policy and program experts in pinpointing where services may need to be developed or improved.

The purpose of the present study was to describe from the perspectives of survivors the barriers to secondary prevention, specifically reporting sexual assault and strategies to improve reporting, prevention programming, and responses to sexual assault survivors in university settings. Our work builds on existing research by using the ecological model as a framework (Dills et al., 2016) and presenting in-depth interview data from a diverse sample of survivors of unwanted sexual experiences such as sexual harassment, unwanted sexual contact (e.g., touching), and sexual violence (i.e., attempted or completed forced penetration).

Theoretical framework

The ecological model, first used in psychology, sought to understand human development in the context of the systems and multiple settings in which it occurred (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). The model has been widely used in public health (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988) and violence research (Heise, 1998; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002). Dills et al. (2016) used the ecological model to discuss campus sexual assault prevention strategies. Even so, survivors’ perspectives were not used to identify campus sexual assault secondary prevention strategies at different levels of the ecological model. The ecological model provides a systematic way to examine both causes and potential solutions to violence from the individual to the systems level. For example, the model has been used to explore factors that lead to post-rape adjustment (Neville & Heppner, 1999) and barriers to reporting assault in prisons and jails (Kubiak, Brenner, Bybee, Campbell, & Fedock, 2016).

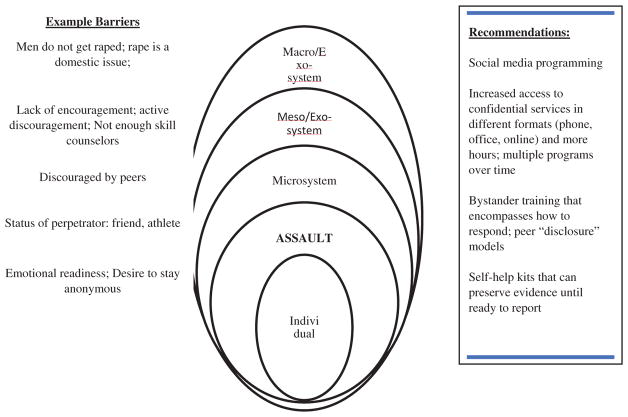

The current study uses the ecological model to frame the discussion of the participants’ perspectives about secondary prevention of campus sexual assault (Figure 1), especially in terms of barriers to reporting. The ecological model’s number and definitions of levels of influence vary by author and context (Bronfrenbrenner, 1977; Campbell, Dworkin, & Cabral, 2009; Dills et al., 2016; Heise, 1998; Kubiak et al., 2016; Neville & Heppner, 1999). Participants’ perspectives in this study are described at the individual, assault, microsystem, meso/exosystem, and macrosystem levels. The individual level refers to characteristics of the survivor—such as their age, race/ ethnicity, gender, personal beliefs, and decisions to disclose—and how these impact secondary prevention. The assault characteristics include the perpetrator and their relationship to the survivor and other factors that are context specific to the assault itself. The microsystem refers to the informal network engaged by the survivor and includes friends, family, and peers. The meso/exosystem can be understood as the formal support system and would include both university-specific resources such as campus security, health clinics, and administrative guidance and the city’s legal and medical resources. Finally, the macrosystem encompasses the overall culture, which still supports rape myths and survivor-blaming norms (Campbell et al., 2009; Rozee & Koss, 2001). In this study, this level would also include general attitudes toward athletes and fraternities and sororities.

Figure 1.

Campus sexual assault secondary prevention barriers and recommendations.

Method

Participants and procedures

This qualitative study is part of larger parent study exploring sexual assault at a large private university. The parent study was a university-wide survey including 12,773 full-time students with 31% response rate (3977/12773). The survey focused on assessing students’ unwanted sexual experiences, personal and university community attitudes toward unwanted sexual incidents, and knowledge about resources and reporting procedures. At the completion of the anonymous survey, students with experiences of unwanted sexual behaviors at the university were invited to participate in a follow-up qualitative semi-structured interview. If they agreed, they were asked to answer basic demographic questions and to provide their contact information. In total, 194 students, or 32% of those who reported experiencing unwanted sexual behaviors in the survey, expressed an interest in being interviewed.

Twenty-seven of the 194 students who indicated interest in being interviewed were purposefully selected to represent heterogeneity in terms of student status (graduate versus undergraduate), gender identity, relationship with the perpetrator, race/ethnicity, and whether they reported the incident. Potential respondents were contacted by phone and/or e-mail for interview appointments. The interviews lasted for 45–60 min. The semi-structured qualitative interview guide covered several topics, including participants’ decisions to seek and experiences of receiving services related to their assault, participants’ advice to other survivors and administrators, and their reactions to taking a survey of this nature. Students who participated received a $25 gift card for their time and effort. An additional separate consent was obtained at the start of the interview according to the study procedures approved by the university institutional review board.

Data analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis involves finding “repeated patterns of meaning” across a data set (p. 6). We took a constructionist perspective in that our focus was less on individual motivation and more on the “sociocultural contexts, and structural conditions, that enable the individual accounts that are provided” (p. 14) as is congruent with the ecological framework. We identified themes and patterns coding for barriers to reporting and suggested strategies for secondary prevention and intervention as we moved through the data.

We followed specific phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) which included reading word for word transcripts in detail, generating initial codes, searching for themes, and then reviewing and, in some cases, renaming themes. Two trained coders independently coded the transcripts using the preliminary coding schemes as guide and created new codes as needed. To ensure credibility of the findings, the coders met at multiple time points to discuss and compare codes and themes and to reconcile any differences that emerged. In the following, we report our findings and then consider these in the context of the ecological model in the discussion that follows.

Results

Sample characteristics

The student survivors included 77.7% (n = 21) females, 18.5% (n = 5) males, and 3.7% (n = 1) from an alternate gender identity. The racial identification of the sample was as follows: Caucasian (44.4%, n = 12), Asian (29.6%, n = 8), mixed race (11.1%, n = 3), Hispanic (7.4%, n = 2), African American (3.7%, n = 1), and one from unknown racial/ethnic background. The majority (62%, n = 17) were undergraduate students as was true of the general survey sample. Nearly 67% (n = 12) reported being heterosexual, 25.9% (n = 7) were bisexual or identified themselves as queer heterosexual, and 7.4% (n = 2) were homosexual. The age range of participants was 19–30 years. The majority were victimized by acquaintances (66.6%, n = 18), followed by a partner/ex-partner (n = 7) and a stranger (n = 2). Regarding type and severity of experiences, 10 students reported experiencing forced completed penetration; 2 reported digital penetration; 3 were assaulted when drunk or passed out and so could not clearly describe the type of assault; 4 reported abuse such as unwanted sexual comments, sexual verbal abuse, and pressure for a relationship; 2 described the incident as an unwanted sexual contact; 4 reported forced oral sex or attempted oral sex; and others either used the term “assault” or did not clearly describe the type of experience.

Findings

In the first half of this section, we describe survivors’ descriptions of barriers to secondary prevention, specifically to reporting and seeking services. In the second half, we describe their recommendations for how to overcome these challenges.

Barriers to reporting

Thirteen survivors disclosed the incident to the counseling center services; however, only five formally reported the event to the authorities. As illustrated in the following, this was often attributed to a sense of futility about making such a report, the personal and social costs of reporting, concerns about confidentiality, and minimization of or fears of reliving the event. Other survivors said they needed time before they could report.

Sense of futility

Almost all participants were overwhelmingly negative about the likelihood of anything positive coming from a report to university authorities or the police. For some, this was related to the climate at the university:

Just especially because university. . . had. . . always reported zero sexual assaults in many years. I just knew that couldn’t be true. I just thought, oh, there’s no way that they’ll take this seriously. (Undergraduate, female, Caucasian)

I hadn’t heard very good things about. . . responses to sexual assault. (Undergraduate, Female, Mixed Race)

For others, there were concerns about not being believed. One student described how her sports team peers were split between believing her versus the perpetrator’s version of events. In another case, there was a lack of evidence or uncertainty about what is considered assault or what “evidence” consists of:

It’s very hard to separate what’s required legally or in terms of an official investigation. . . in those cases to establish the burden of proof versus what’s in your mind and in your memory about what happened. I didn’t want my already very confused mind to be undermined by a process that would almost inevitably not pan out, because there was no evidence. (Graduate, female, Caucasian)

One survivor shared that the length of the reporting process is a barrier to reporting: “People think there’s a lot of red tape that you have to go through and that it’s more trouble than it’s worth” (undergraduate, female, Caucasian).

Others did seek assistance but were told by persons in authority that going further would be futile, even risky. One woman, who disclosed her assault to campus security, was told that the perpetrator’s lawyer would point out that she and her friends were drinking and that in addition to not being able to prove anything, she would be putting her friends at risk. This exchange effectively ended the student’s interest in reporting the event. This sense of futility has to be weighed against the potential personal and social costs to making a report.

Personal and social costs of reporting

Some survivors did not report incidents because of the potential social impact for themselves and others. This included fear of being rejected by social circles:

I just want to move on and not talk in depth with anyone . . . to remove myself from him is to remove myself from his circle of friends . . . I had gotten close to some [of his] friends . . . and I didn’t want to alienate myself. (Undergraduate, female, Hispanic)

Another participant weighed her decision not to report a man who sexually assaulted her multiple times against the social costs:

What, I am never supposed to go to that apartment again? I’m a junior and I don’t have time to make a new friend group. I’d rather live with [him] being creepy than have to get a new friend group. (Undergraduate, female, Hispanic)

Others hesitated to report because they were protecting other survivors, and sometimes the perpetrator themselves. One survivor did not report because her friend was also involved in the incident, and if she reported it, her friend’s identity would be revealed.

I felt that if I reported what happened to me, through the investigation process they would find out what happened to her . . . and she would be dragged into the process that she didn’t want to be a part of. I didn’t want to betray her trust, because she was really struggling with anxiety and depression after it happened. (Undergraduate, female, Caucasian)

For others, the impact on the perpetrator was a barrier to reporting: “Since I’ve been friends with this guy for so long, I didn’t want anything happening to him because I guess I would’ve felt guilty” (Graduate, Female, Caucasian).

For another survivor, the perpetrator’s status was a deterrent to reporting:

Since he [the perpetrator] is high profile, it’s not a good idea to have police involved . . . I’m not afraid of not winning or people not believing me, it was just more like I didn’t want to be dragged out in front of the public eye and have my entire life examined. (Undergraduate, female, Caucasian)

The potential for having to relive the event during the reporting process was an additional barrier for some:

When you have to explain the event, you have to go back and relive it . . . when you have to relive the event it does make you second guess if reporting it is really worthwhile . . . Having to explain the entire event in detail on the online form to then go in and explain it once more to a person is a bit difficult on the victim of the assault. (Undergraduate, female, Hispanic)

Another woman added: “I was just dealing with other things. I was depressed and suicidal and going and reporting to the police was just another burden that I would never have wanted to do” (undergraduate, female, Asian).

It was clear that perceived potential costs to reporting-social isolation, not being taken seriously, having to relive the event outweighed any perceived benefit.

Concerns about confidentiality

Whether the fears were related to the fallout to themselves, their friends, or their perpetrator, confidentiality, and the ability to protect it, was paramount. For example, one participant shared his friend’s reason for not reporting: “She thought that her name would just have been plastered over every publication on campus. . . She’s the kind of person to err on the side of cynicism and understand that the system doesn’t always deliver” (undergraduate, male, race/ethnicity unknown).

Many participants directly connected a loss of confidentiality to an additional unwanted loss of control: “If you were to say anything about a rape, they’re obligated by law to report it. I just felt there weren’t that many resources that I could talk to without completely losing control of the situation” (undergraduate, female, Caucasian).

A sense of futility, fear of a negative social impact, desire to protect others, and loss of confidentiality combined to form a powerful disincentive to reporting. One survivor stated:

There’s always the dilemma of ‘do I want to ruin this person’s life who did it to me,’ and then the stigma of you are ‘that girl’. . . People don’t believe you. If I did a report, it would get out. It would be public. There would be a stigma attached to me. (Undergraduate, female, Caucasian)

Another survivor shared: “We went through a rough patch, but now we’re like, who would want to be the buzz kill to say, All right, let’s go talk about rape with the administrators on campus. Let’s go uncover this thing again” (graduate, male, Asian).

Minimization of the event

Minimizing the assault experience led some students to question if services were actually for them or not. One student commented:

I didn’t think it was serious enough. I felt like this isn’t a university issue. This is just like an issue in the domestic space. I should just go with it myself. I didn’t want to make the situation worse by filing a complaint. (Graduate, female, Caucasian)

Other students shared:

If I felt extremely unsafe, then I could have forced my way out of the situation, but I didn’t. That was the threshold of whether I should bring this to authorities or not is whether I felt so unsafe that I wanted to leave the situation by force, but I didn’t feel that was the case. (Graduate, male, unknown race).

I didn’t think that it was worth reporting since the person was drunk as well. (Undergraduate, female, Asian)

I had this idea in my head that only people who are drugged and raped, who have to go to the hospital were really the people who should be. . . dragged in all these issues. (Undergraduate, female, African American).

Suggested strategies for prevention and intervention

Although more limited than what students shared about barriers, students did have some specific suggestions for what policy and program authorities could consider doing to improve secondary prevention services on campus and increase the likelihood that survivors would access services.

Programs on sexual assault

Students recommended that programs on sexual assault should teach students not only not to engage in sexual assault but also how to deal with incidents and talk about their experience. Educational events should be interactive and engaging and provide a platform for students to discuss these issues openly. The content could be presented in a way that both normalizes sexual assault reporting, but also treats such situations as serious infractions. Further, it was mentioned that more students would come forward to report if they felt there was a norm around reporting sexual assault issues and that it is okay to discuss these issues openly. For students who do not know the process, it would be intimidating for them to approach services they do not fully understand. Therefore, the programs should cover details of the reporting process and what to expect when survivors decide to report. For example, a male survivor shared:

Students don’t know what to expect when they use these services. Without an expectation of what the procedure is, I think students are very off-put by that . . . I still don’t understand the process, so it would be very intimidating to approach something that you don’t fully understand. (Graduate, male, Asian)

Some students suggested that programs on sexual assault should also include success stories from survivors’ experiences with reporting and how it helped them. Not knowing if anyone used existing resources was considered a barrier to reporting. For instance, a female student stated:

The biggest barrier for me was I knew that these things existed, but I didn’t really know anyone who had used them. I feel if you would hear about people actually accessing some of these things more, that it would seem more approachable to me. (Graduate, female, Asian)

A male survivor suggested gender-inclusive messages in the programs to reduce stigma around male victims. Another point of advice was gender sensitivity of trainings and not to have male and female students in the same room during trainings. According to some students, bystander intervention trainings (training students to intervene to prevent possible sexual assault) could be very effective in making survivors comfortable in reporting to authorities. Trainings would help them realize that reporting will not have a negative impact and may provide opportunities to discuss the assault. Also, training should teach students how best to respond if a friend discloses an experience of sexual assault. This was particularly important for new students who are not aware of the system and find friends to be their best resource for sharing their experiences of sexual assault. For instance, one survivor stated:

I really think that it’s just other students that people are going to feel comfortable talking to . . . when freshmen are sexually assaulted in their first two weeks of school, they don’t feel close enough to anyone at all. I think that just students are the best resource for this. (Undergraduate, female, Hispanic)

Increased awareness of services

Students shared the need to increase awareness about sexual assault services on campus so that survivors can benefit from existing resources such as the counseling center or student assistance program. Some students knew the names of the services but did not know what these services included or how to access them.

I can’t recall a time during my freshman orientation where there was some sort of programming event where they really talked about what do you do if you witness this happening, what do you do if you find out that your friend, this has happened to them, what do you do if it happens to you? I don’t think we ever talked about it. (Undergraduate, female, Latina)

Suggested strategies to raise awareness included distributing phone numbers on the back of university ID cards, putting a list of resources in women’s restrooms, posting flyers with resources around campus, distributing brochures, and also sending out periodic e-mails to students to let them know that resources are available. A few graduate students shared that they were unaware of or did not feel that they were a part of the community served by these resources. A female graduate Asian student recalled: “Well I think it’s different—it’s like a grad student—I don’t know. I think it’s just the people that I’m friends with don’t use services, and I think, as a grad student, you feel a little separated . . ..”

Therefore, there is a need to include graduate students in the dissemination of information regarding resources for survivors. There was indication that students felt that the university’s attitude toward sexual assault needed to be more overt. A few respondents noted that the sexual assault survey “showed that the university is taking a proactive approach” (graduate, male, Asian) and taking the “right steps” by addressing assault in general. They also felt like that the survey gave victims an opportunity to let victims’ stories be heard. Thus, repeated surveys with opportunities for in-depth interviews could strengthen university’s sexual assault prevention and intervention efforts.

Need for additional staff for addressing sexual assault and sexual misconduct on campuses and staff training

A few students highlighted the need for more staff training on trauma-informed services, including sexual trauma counseling and best practices to respond to survivors of sexual assault. The students emphasized the importance of a nonjudgmental attitude when working with survivors and giving them time to recover or to clear their mind before getting information from them. Others suggested strategies to help care for survivors, including “being real” and “not treating survivors as a different person,” presenting multiple resources from which to choose, giving survivors choice in the process or what the outcome should be for the perpetrator, and not denying services based on subjective opinion about what could have happened. Caring and supportive aftercare services were reported as crucial for healing and preventing negative coping such as the use of drugs.

Students made specific recommendations about improving access to and the timeline for counseling services. Access issues included enhancing the hours students can contact counselors as well as diversifying the format of the exchange. For example, students advocated for online chat and texting options that could remain anonymous and be available at any hour or day. For in-person visits, students stressed how important it was that the office not be easily identifiable to others, and that they not have to repeat their story again and again.

One student stressed how important it was to move the care process forward in a timely manner to avoid or minimize unhealthy coping:

You have to very quickly capture the person into a caring narrative and structure so that they can immediately start a healing process instead of a destructive process. University is the perfect place to be destructive. You’re away from home. You can stay out all night, and no one’s really going to notice. You can do drugs . . . start having sex with people that are not very nice to you. It will be good if we can encourage those people very quickly to be able to label the experience as an act of violation and then put them into structures of care. (Graduate, female, Caucasian)

Need for additional resources

Students shared specific suggestions for resources that could be added to strengthen services for sexual assault survivors on campus. These resources included (a) campus-based support groups for survivors so that they can share their experiences with peers who have gone through similar experiences; (b) 24/7 phone services/hotline for those who just need to speak with someone anonymously and not press charges or take action against the perpetrator; (c) easy access to self-help/rape kits on campus for survivors who are hesitant to go to the hospital or the emergency room; (d) an anonymous online chat room/texting services through the university for survivors who are not comfortable talking about the experience; and (e) an office with staff available 24/7 for support. Many students described the importance of anonymity and confidentiality of resources. One student mentioned that even the location of the office for sexual assault services (where students going for help are likely to be seen by other students) could deter survivors who do not want to be seen walking in for help. Thus, there needs to be a way that students who visit the office to maintain their privacy, as reflected in the following quote:

It would be helpful to de-localize the office in the sense that if someone doesn’t want to be seen walking in there or doesn’t want to actually make the effort to walk there—because that can be emotionally exhausting in its own way—if there would be a way for people to actually be dispatched to students’ rooms- that might be helpful because I think safe space takes on a new definition after a sexual assault, where you want to be in your own space. (Graduate, female, Caucasian)

Discussion

We explored a diverse group of student survivors’ perspectives about barriers to and recommendations for improving secondary prevention services regarding sexual assault. To be able to provide secondary prevention interventions, survivors must first report an event to someone. Our results suggest that barriers to reporting are found at all levels of the ecological framework. For example, at the individual level, an individual’s mental health status or strong desire to protect oneself from a possible loss of confidentiality prevented reporting. An example of a microsystem barrier was worrying about not being believed by peers which prevented a survivor from making an official report. Macrosystem barriers to reporting included the idea that “real” rape always involves some kind of incapacitation of the victim, that women who report assault will be stigmatized, or that rape is a ‘domestic’ issue and should be dealt with privately.

A large number of barriers clustered around the meso/exosystem level. For example, survivors’ sense of futility was often linked to how seriously they felt their claims would be taken, or if they would even be believed by university and city police. Others were directly discouraged from reporting (e.g., by campus security). Fear of distress caused by sharing their experience, potentially multiple times, at the meso/exosystem level, was also a strong disincentive to reporting.

Barriers that were connected across levels have the potential to be particularly influential. For example, a survivor’s hesitancy to report her own rape was influenced by a campus security personnel’s suggestion that doing so would put the friends in her microsystem at risk for punishment by the meso/exosystem elements—in this case police—because they were underage. Individual-level decisions to not disclose were influenced by a lack of confidence in the mesosystem’s functionality and fairness. The macro system’s glorification of athletes contributed to one individual’s fear that she would not be believed.

In terms of survivors’ recommendations for improving secondary prevention efforts, they made suggestions for interventions at all levels of the ecological model. Individual-level interventions included programs to help students cope with an assault at a personal level. Several survivors endorsed interventions at the microsystem level. This included bystander intervention programs as well as a proposed training so that a friend or peer could respond to a disclosure in the most therapeutic, knowledgeable manner possible. While positive reactions and support from friends and family can have beneficial effects, negative reactions can lead to psychological distress for survivors (Banyard, Moynihan, Walsh, Cohn, & Ward, 2010). Thus, prevention efforts should focus on education, awareness, and providing concrete suggestions about appropriate language to use or actions to take when someone discloses (Banyard et al., 2010). Also at this level, students described the potential value of having access to peers’ stories who had reported so that they could better understand how their own disclosure might play out. Having these ‘disclosure models’ would give confidence to individuals considering reporting and demystify what seems to be a very intimidating process for students. Post-disclosure, having access to a peer network of survivors was another suggestion at the microsystem level.

At the meso/exosystem level (i.e., the university and city level), students had several specific recommendations. These recommendations included availability of services in which the reporting process is more transparent and more rigorous in terms of protecting survivors' confidentiality. The staff providing services to survivors need to be highly trained and easily accessible when needed. Their specific suggestions, such as 24-hour hotlines, online chat rooms or texting services, and ensuring a private location for the office that provides services for survivors, were all geared toward achieving greater accessibility and confidentiality at the meso/exosystem level. Survivors also suggested the availability of self-help resources or rape kits for those who do not want to go to the hospital/emergency room. More information needs to be conveyed to students and to all parts of the system regarding the nature of a sexual assault exam, that it is not just collection of DNA evidence but an inch-by-inch head-to-toe skin exam with a sensitive interview by a trained nurse that can do much to establish consent or lack thereof. There is also a need for sexual assault victims to understand that the exam can be done without a report to the police so that the evidence can be collected and a decision made about police involvement later (Laughon, Fontaine, & Bullock, 2015). Moreover, training university staff at the meso/exosystem level on adequate trauma-informed care for survivors who disclose their experience was highlighted as a critical component. Some survivors in our study expressed discomfort with having to retell their stories during the reporting process. This highlights the need to minimize the number of university staff the survivor needs to tell about the trauma. However, talking about and processing the trauma is a hallmark feature of the empirically supported treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (e.g., cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure). This sharing of the story, therefore, could be one of the goals within the context of a supportive therapeutic environment.

Macrosystem norms, including that men are not assaulted, could be addressed with gender-inclusive programming and social media messaging that debunks this myth, thereby making it more comfortable for men to report. The impact of time on survivors’ readiness to engage with services suggests that services need to be repeatedly offered, even to the same group of students, in order to increase the chances that the timing will be right for someone processing their assault. Future campus programming cannot be limited to improving services only, but should continue to incorporate education about assault, its definitions, and consequences. Since sexual assault may also occur off-campus or reported to noncampus authorities, universities are advised to consult and coordinate procedures with campus and noncampus healthcare providers, police, and other providers providing services to survivors of sexual assault (American Association of University Professors, 2012).

Input from survivors is critical to developing strong prevention and intervention programs. The strengths of our study include identification of factors at multiple levels of the ecological contexts that could be considered in secondary prevention of sexual assault in university settings. The findings are based on the perspectives of diverse groups of survivors. This study was based on self-report and is therefore limited by retrospective bias and survivors’ willingness to share information. The participants were all from one large private university. Future research should include different types of university settings in different geographical locations to best understand barriers to help-seeking and services needed to address the issue at the national level. Nonetheless, this study provides an important contribution to the efforts toward developing effective sexual assault prevention and intervention programs on university campuses. Despite many available services for sexual assault survivors at the university such as emotional support and counseling; a sexual assault hotline; a peer support program (a volunteer student group that refers survivors to resources); a sexual assault prevention, education, and response coordinator; and medical care, the majority of students in the study did not file a formal complaint. The findings, based on shared experiences from a diverse sample of survivors, shed light on key barriers to reporting or seeking help. Further, findings highlight elements of campus sexual assault prevention and intervention strategies that are sensitive to these barriers as well as to students’ needs. We argue that the ecological framework is a valuable tool for examining the barriers that exists in university campuses, and the potential solutions, with respect to secondary prevention for campus sexual assault.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Johns Hopkins University Provost Office; Dr Sabri was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development [K99HD082350]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report by any author.

Ethical standards and informed consent

All study procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/wamt.

References

- Ahrens CE, Campbell R, Ternier-Thames NK, Wasco SM, Sefl T. Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of rape survivors’ first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(1):38–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00329.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of University Professors. Campus sexual assault: Suggested policies and procedures. 2012 Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/report/campus-sexual-assault-suggested-policies-and-procedures.

- Anderson ET, McFarlane JM. Community as partner: Theory and practice in nursing. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Walsh WA, Cohn ES, Ward S. Friends of survivors: The community impact of unwanted sexual experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(2):242–256. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens MR. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. Available from http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/11735. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfrenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32(7):513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Dworkin E, Cabral G. An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2009;10(3):225–246. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Townsend R, Lee H, Bruce C, Thomas G. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.aau.edu/uploadedFiles/AAU_Publications/AAU_Reports/Sexual_Assault_Campus_Survey/AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdf.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual violence: Consequences. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/consequences.html.

- Dills J, Fowler D, Payne G. Sexual violence on campus: Strategies for prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, and Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. An evaluation of three brief programs for facilitating recovery after assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(1):29–43. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1573-6598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassija CM, Turchik JA. An examination of disclosure, mental health treatment use and posttraumatic growth among college women who experienced sexual victimization. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2016;21(2):124–136. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2015.1011976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42495/1/9241545615_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP, Brenner H, Bybee D, Campbell R, Fedock G. Reporting sexual victimization during incarceration: Using ecological theory as a framework to inform and guide future research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;19(1):94–106. doi: 10.1177/1524838016637078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughon K, Fontaine D, Bullock L. Violence on campus: We all have a role to play. Journal of Nursing Education. 2015;54(5):239–240. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150417-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Heppner MJ. Contextualizing rape: Reviewing sequelae and proposing a culturally inclusive ecological model of sexual assault recovery. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1999;8(1):41–62. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(99)80010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozee PD, Koss MP. Rape: A century of resistance. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2001;25:295–311. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabina C, Yo LY. Campus and college victim responses to sexual assault and dating violence: Disclosure, service utilization, and service provision. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2014;15(3):201–226. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Danis F, Mauzy DL, Gallagher SK. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: Perspectives of college students. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55(3):157–162. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.3.157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House. Climate surveys: Useful tools to help colleges and universities in their efforts to reduce and prevent sexual assault. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.notalone.gov/assets/ovw-climate-survey.pdf.

- Zinzow HM, Thompson M. Barriers to reporting sexual victimization: Prevalence and correlates among undergraduate women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20(7):711–725. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.613447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]