Abstract

Comprehensive mandate of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which requires both registration and use of PDMPs in most clinical circumstances, has the potential to improve provider participation and reduce opioid-related adverse events. Using the Medicaid prescription data and hospital utilization data across the U.S. between 2011 and 2016, we found that state implementation of comprehensive PDMP mandates was associated with a reduction in opioid prescription rate from 161.47 to 147.07 prescriptions per quarter per 1,000 enrollees, a reduction in opioid-related inpatient rate from 97.50 to 93.34 stays per quarter per 100,000 enrollees, and a reduction in opioid-related emergency department (ED) visit rate from 74.60 to 61.36 visits per quarter per 100,000 enrollees. Our estimated annual reductions of approximately 12,000 inpatient stays and 39,000 ED visits can save over $155 million in Medicaid spending, which deserves policy attention when states attempt to strengthen and refine PDMPs to better tackle the opioid crisis.

The opioid epidemic has reached crisis levels in the United States. The economic cost of the crisis was estimated at $504 billion in 2015, or 2.8 percent of the total gross domestic product (GDP).1 One key contributor to the opioid epidemic is the inappropriate prescribing of opioids for pain management.2–5 Despite the recent levelling off and gradual reduction in opioid prescribing, the rate in 2015 remained three times higher than that in 1999.6 Furthermore, rates of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits have been increasing rapidly during the recent years.7 Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) have been recognized as one of the promising tools to regulate opioid prescribing practices and slow the epidemic.8–10 These statewide electronic databases collect and monitor the prescribing and dispensing information on controlled substances to help providers identify high-risk individuals and high-risk patterns such as high dosage prescriptions, dangerous drug combinations, and multiple-provider episodes.11

Although PDMPs have been established in almost every state, participation in PDMPs varied across states and remained generally low, which limited the effectiveness of PDMPs.11–24 Therefore, state policy effort in recent years has shifted from simply establishing PDMPs to improving provider participation in the programs. Prominent policy strategies include a “registration mandate” that requires all state-licensed prescribers and dispensers to enroll in PDMPs and a “use mandate” that requires registered providers to consult PDMPs under certain clinical circumstances.11, 13–16 Note that the definition and inclusiveness of the mandatory circumstances varies from state to state and as a result so does the strength of these use mandates.11, 13

In July 2012, Kentucky implemented the nation’s first comprehensive PDMP mandate, which can be viewed as a “registration mandate” plus a “strong use mandate”. Kentucky’s mandate requires all prescribers and dispensers to register with Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Electronic Reporting System (KASPER, Kentucky’s PDMP) and use the system before the initial prescribing of any Schedule II-IV substance and at least every three months thereafter.25 Kentucky and several other states that had followed suit and implemented comprehensive PDMP mandates saw rapid increases in registration and use of PDMPs.26

Using Medicaid prescription data and hospital utilization data between 2011 and 2016, we estimated the association of comprehensive PDMP mandates with the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits. Our findings provide much needed evidence to inform state policy discussions about strengthening and refining PDMPs to better tackle the opioid crisis.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

Data

Our opioid prescription data were derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)’s State Drug Utilization Data, which provided the quarterly number of all outpatient drug prescriptions covered by Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care in all 50 states. The opioid-related hospital use data were from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Files, which provided the quarterly numbers of inpatient stays in 45 participating states and of ED visits in 31 states.

We used data from the first quarter of 2011 to the last quarter of 2016, which captures the emergence and acceleration of comprehensive PDMP mandates.

Measures

Our first outcome of interest was opioid prescription rate, defined as the number of opioid prescriptions covered by Medicaid on a quarterly, per 1,000-Medicaid enrollee basis. We identified opioid prescriptions using National Drug Code (NDC) numbers and grouped them into Schedule II vs. III-V opioids, based on the Controlled Substance Act (CSA) scheduling. Schedule II opioids are generally considered to have a higher abuse and overdose liability. We classified hydrocodone combination products as Schedule II throughout the study years, to be consistent with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) rescheduling in October 2014.27 Buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone prescriptions for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of opioid use disorder were excluded from opioid prescription rate. In addition to prescription opioids, we also studied the non-opioid pain medications (e.g., selective acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, anticonvulsants such as pregabalin, gabapentin, and carbamazepine, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), etc.). (Appendix A1 provides a detailed list of non-opioid pain medications).28 In supplementary analyses, we studied the prescription rate of buprenorphine for MAT to capture one of the potential areas of change in opioid use disorder treatment.

The second and third study outcomes were the rates of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits, defined as the number of Medicaid-covered inpatient discharges and ED discharges related to opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence on a quarterly, per 100,000-Medicaid enrollee basis. We used the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) diagnostic codes to identify discharges related to opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence. (Appendix A1 provides a detailed list of opioid-related ICD codes).28

The key independent variable was an indicator for state implementation of a comprehensive PDMP mandate (i.e., registration mandate and strong use mandate). To be considered comprehensive, a PDMP mandate must meet the following criteria: (1) all providers, regardless of practice settings and specialties, are subject to the mandate; (2) providers are required to check PDMP upon initial prescribing and at least every twelve months thereafter if prescriptions are to continue; (3) providers are not allowed to rely on their own judgment to determine whether it is necessary to check PDMP in individual cases. The “comprehensive mandate” indicator was assigned a value of 1 for each full quarter subsequent to the effective date of the mandate in a state, and a value of 0 for the pre-comprehensive mandate quarters and for comparison states. Furthermore, we created a “non-comprehensive mandate” indicator for the implementation of other types of state PDMP mandates that fell short of the comprehensive mandate criteria (i.e., registration mandate only, weak use mandates only, and registration mandate and weak use mandate). (Appendix A2 provides a policy summary of state PDMP mandates).28

Statistical Analyses

We used a quasi-experimental, difference-in-differences design to examine the association of comprehensive PDMP mandates with the study outcomes. We used a two-way fixed effects approach, which is an extension of the traditional two-group, two-period difference-in-differences design to a multi-group and multi-period setting.29 We included state fixed effects to account for between-state differences that did not vary over time and year-quarter fixed effects to account for secular trends in study outcomes that were common to all states (e.g., the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 in late 2015, the rescheduling of hydrocodone in October 2014, and the scheduling of tramadol in August 2014).30 We further inspected the trajectories of opioid-related inpatient and ED visit rates before and after the ICD-9 to ICD-10 transition, as well as the association of PDMP mandates on the rescheduled hydrocodone in particular (Appendix A3 and A8).28

All analyses controlled for state-level measures of physician supply, general economic conditions, concurrent state policies such as pain clinic regulations, Medicaid expansions and marijuana laws, as well as division-specific linear trends to account for the unobserved Census division-wide confounding factors such as trajectory pattern and public sentiment that evolve over time at a constant rate. (Appendix A1 provides the detailed model specifications and Appendix A4 provides the descriptive statistics of the study variables).28 The estimates were weighted by the state population,31 and standard errors were clustered at the state level using Stata/SE Version 15 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). Clustered standard errors allow for arbitrary within-state correlation in error terms but assume independence across states.32 We performed tests of the “parallel-trend assumption” by comparing the pre-mandate trends between states with comprehensive PDMP mandates, states with non-comprehensive mandates, and the comparison states. The test statistics lent weight to the validity of the methods (Appendix A5).28 Note that our difference-in-differences indicator of comprehensive PDMP mandates captures the average policy effects across all states with the comprehensive mandates during the entire post-mandate periods. Although we did not have sufficient statistical power to estimate the potential state-specific heterogeneous effects, we did a robustness check by excluding the comprehensive-mandate states one at a time. We also estimated the linear and quadratic trajectories of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits associated with PDMP mandates (Appendix A11).28 Furthermore, we provided a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the savings in health care costs, based on our estimated changes in opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits nationwide and previous national estimates of the average annual Medicaid costs per opioid-related inpatient discharge and per ED discharge from HCUP and the Medicaid enrollment data from CMS.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, policy decisions to adopt comprehensive PDMP mandates were not “randomly assigned” to states. Although we controlled for state variations in physician supply, general economic conditions, and concurrent policies, as with any observational study, we cannot definitively establish causal chain from comprehensive mandates, through opioid prescribing, to opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits.

Second, the prescription data lacked the necessary information to adjust our measurement of prescription rates for the variations in formulation, strength, and dosage or to generate more standardized values such as morphine milligram equivalents (MME). Nonetheless, we found that the reductions in opioid prescription rate associated with comprehensive PDMP mandates were largely concentrated in Schedule II opioids. This finding, to some extent, alleviates the concern that the reduction in overall prescription rate might be a result of substitution of prescriptions with higher MMEs for those with lower MMEs.

Third, our inpatient and ED data lumped all the opioid-related diagnostic codes together. Thus, we were unable to separate out each type of opioids (e.g., prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids) or each type of conditions (e.g., overdose, abuse, and dependence). Nonetheless, from the societal and policymakers’ perspective, a net change in all opioid-related hospital use is still meaningful.

Finally, our data did not include fatal overdoses or the overdose events that were fully reversed through naloxone administration by laypersons or first responders without entering a hospital. To the extent that these overdoses were more likely to be associated with illicit opioid use, our findings may not adequately capture the potential unintended consequences of restricted access to prescription opioids under PDMP mandates.

STUDY RESULTS

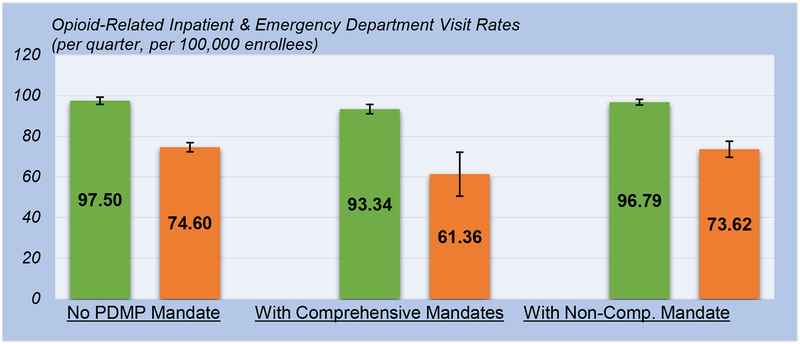

State implementation of comprehensive PDMP mandates was associated with a lower rate of opioid prescriptions for Medicaid enrollees (Exhibit 1, Appendix A6, and Appendix A7 Column 1).28 Specifically, the estimated number of opioid prescriptions per quarter per 1,000 enrollees was 161.47 without PDMP mandates (95% CI: 157.70, 165.23), compared to 147.07 with the implementation of comprehensive mandates (95% CI: 136.98, 157.17) and 155.41 with the implementation of non-comprehensive mandates (95% CI: 143.44, 167.37). The change in opioid prescription rate associated with comprehensive mandates can be translated to a relative 8.91 percent reduction, whereas the change associated with non-comprehensive mandates was not statistically significant.

EXHIBIT 1 (Figure).

Association of Comprehensive and Non-Comprehensive Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) Mandates with Opioid Prescription Rates.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the CMS State Drug Utilization Data 2011–2016.

NOTES:

Point estimates shown as colored bars; the prescription rate of all opioids as green bars and the prescription rate of Schedule II opioids as orange bars; 95% confidence intervals clustered at the state level shown as lines with bars.

The reduction in opioid prescription rate associated with comprehensive mandates was concentrated mainly in the prescription rate of Schedule II opioids (Exhibit 1, Appendix A6, and Appendix A7 Column 2). We found a reduction from 121.44 per quarter per 1,000 enrollees without mandates (95% CI: 118.06, 124.81) to 112.41 with the implementation of comprehensive mandates (95% CI: 111.12, 113.70), equivalent to a 7.44 percent reduction. On the other hand, we found no discernable change in the prescription rate of Schedule III-V opioids associated with the implementation of comprehensive mandates or non-comprehensive mandates (Appendix A7 Column 3). The change in the prescription rate of non-opioid pain medications associated with the implementation of comprehensive mandates was positive, albeit imprecisely estimated (Appendix A7 Column 4).

Our supplementary analyses found that the prescription rate of buprenorphine for MAT was higher with comprehensive mandates than without any PDMP mandate (9.23 vs. 8.59 per quarter per 1,000 enrollees). Nonetheless, the difference in buprenorphine prescription rate was not precisely estimated and not significant at the 0.05 level (Appendix A9).28

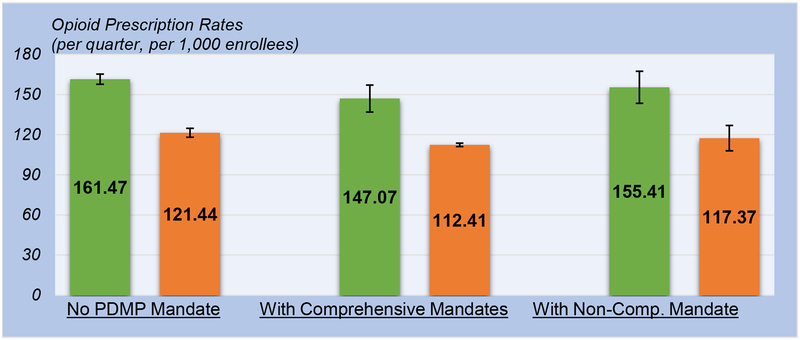

Regarding the rates of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits (Exhibit 2, Appendix A6 and A10), we found significant reductions associated with comprehensive mandates. Specifically, the implementation of comprehensive mandates was associated with a 4.26 percent reduction (95% CI: −8.49, −0.03) in the number of opioid-related inpatient discharges, from 97.50 (95% CI: 95.70, 99.31) to 93.34 (95% CI: 91.02, 95.66) per quarter per 100,000 enrollees. Furthermore, we found a 17.75 percent reduction (95% CI: −35.25,−0.25) in the number of opioid-related ED discharges associated with the implementation of comprehensive mandates, from 74.60 (95% CI: 72.33, 76.86) to 61.36 (95% CI: 50.57, 72.15) per quarter per 100,000 enrollees. No discernable change in these outcomes, however, was found to be associated with the implementation of non-comprehensive mandates.

EXHIBIT 2 (Figure).

Association of Comprehensive and Non-Comprehensive Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) Mandates with Opioid-Related Inpatient and Emergency Department (ED) Visit Rates.

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of the AHRQ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2011–2016.

NOTES:

Point estimates shown as colored bars; opioid-related inpatient rate as green bars and opioid-related ED visit rate as orange bars; 95% confidence intervals clustered at the state level shown as lines with bars.

We did a robustness check by excluding the comprehensive-mandate states one at a time to estimate the potential state-specific heterogeneous effects. The main findings were generally robust except when we excluded New York, suggesting that New York, with one of the earlier and the strongest mandates, may have been a major contributor to the reductions in opioid prescriptions and related adverse events. Furthermore, the estimates for the linear and quadratic trajectories of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits suggest that the reductions were both immediate following the implementation of the comprehensive mandates and sustained thereafter. However, there might be diminishing marginal returns in the long run (Appendix A11).28

To better understand the policy and financial implications of the reduced opioid-related hospital use associated with comprehensive PDMP mandates, we provided a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the savings in health care costs. We used the national estimates of the average annual Medicaid costs per opioid-related inpatient discharge and per ED discharge from HCUP (approximately $8,000 and $1,500 in 2016, respectively), and the Medicaid enrollment data from CMS (approximately 73,000,000 in 2016). Our estimated annual reductions of approximately 12,000 inpatient stays and 39,000 ED visits can save over $155 million in Medicaid spending alone. There would be even more substantial savings in productivity loss–a major component of the economic burden of the opioid crisis.1

DISCUSSION

Our study provides empirical evidence that the implementation of comprehensive PDMP mandates between 2011 and 2016 was associated with an 8.91percent lower rate of opioid prescriptions in the Medicaid population. The study findings are consistent with those from previous studies that focused on the Medicare and privately-insured populations.33–35 Our focus on Medicaid is important in the context of the current opioid crisis, because the Medicaid population shown to have disproportionately high risks for chronic pain, as well as opioid misuse and overdose.36 The only multi-state Medicaid study on the association between PDMP mandates and opioid prescribing was limited by the small number of comprehensive mandate states and short post-mandate periods.37 By using the most updated data, our study extended the number of comprehensive mandate states from three to ten and the length of post-mandate periods by eight more quarters. We also extended the scope of studied outcomes to non-opioid pain medications and buprenorphine prescriptions.

In addition to opioid prescription rate, we also found reductions in the rates of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits by 4.26 percent and 17.75 percent, respectively, associated with comprehensive PDMP mandates. These potential downstream effects of comprehensive mandates had not been investigated before in multi-state studies. Our findings suggest that the previously documented reductions in overall rate and high-risk opioid prescriptions may have effectively translated into reductions in adverse health care events as a result of opioid misuse and overdose.

An often voiced concern is that the proliferating state policies to restrict access to prescription opioids may push those who already developed dependence on opioids to seek alternative, more dangerous, drugs such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl. This phenomenon has been associated with the reformulation of OxyContin in 2010.38, 39 Due to the aggregated nature of the data, as well as the structure and limited sensitivity and specificity of the ICD diagnostic codes for identifying opioid-related events, we were unable to distinguish the changes related to prescription opioids from those related to illicit opioids. Therefore, we cannot rule out the fact that the implementation of comprehensive mandates may have been associated with an increase in the adverse events related to heroin and synthetic opioids, although that increases, if any, were offset by the reduction in prescription opioid-related events.

A plausible explanation of the overall reduction in opioid-related hospital use is that comprehensive PDMP mandates not only prompt the registration and use of PDMPs, but also help promote referrals to opioid use disorder treatment.40 Timely and effectively identifying the high-risk individuals with the assistance of PDMPs created an opportunity for intervention: a survey found that over a third of providers would refer their patients to treatment when suspicious misuse behavior was noted in the system.40, 41

Concerns have been voiced over the potentially modest effect of PDMPs on overdose reduction based on simulation forecasts of how the epidemic might unfold in the next decade.42, 43 But to the extent that PDMP mandates may help reduce inappropriate prescribing and diversion, and enable physicians to identify those in need of opioid use disorder treatment, they should still be an integral part of a comprehensive, multipronged strategy to abate this public health crisis. Furthermore, the interaction effect of PDMP mandates and other opioid-related policies and interventions (e.g., marijuana liberalization, medication-assisted treatment expansion) merits future research.

Future research may also examine the changes in opioid prescribing for different patient populations (e.g., opioid naïve, acute pain patients vs. long-term opioid use, chronic pain patients).44 In the implementation of PDMPs, certain adjustment and exclusion may be needed for specific subpopulations. Furthermore, adverse events related to heroin and synthetic opioids need to be studied separately from those related to prescription opioids to shed light on the potential unintended consequences of PDMP mandates and other restrictions on opioid prescribing. Future research may also explore other policy innovations designed to improve the accessibility of PDMPs such as streamlining the registration processes, improving the user-friendliness of the system, allowing prescribers to authorize designees, and integrating PDMPs into electronic health information systems.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that the implementation of comprehensive PDMP mandates, requiring both registration and use of PDMPs in most clinical circumstances, was associated with reductions in the rates of opioid prescriptions and the rates of opioid-related inpatient stays and ED visits.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), Executive Office of the President of the United States. The underestimated cost of the opioid crisis [Internet]. Washington, DC: The White House; 2017. November 19 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/The%20Underestimated%20Cost%20of%20the%20Opioid%20Crisis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Ilgen MA, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011. April 6;305(13):1315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. New England Journal Medicine. 2016. January 14;2016(374):154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. American Journal of Public Health. 2018. February;108(2):182–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madras BK. The surge of opioid use, addiction, and overdoses: responsibility and response of the US health care system. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017. May 1;74(5):441–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, Losb J, Lewis B, Young R, et al. Vital Signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2017. July 7;66(26):679–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barrett ML, Steiner CA, Bailey MK, O’Malley L. Opioid-related inpatient stays and emergency department visits by state, 2009–2014 HCUP Statistical Brief #219 [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. December [cited 2019 Apr 25]. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016. April 19;315(15):1624–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, Benyamin R, Glaser SE, Adlaka R, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’(ASIPP) Guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008. March 1;11(2 Suppl):S5–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volkow ND, McLellan TA. Curtailing diversion and abuse of opioid analgesics without jeopardizing pain treatment. JAMA. 2011. April 6;305(13):1346–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL). Prescription drug monitoring programs [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 Apr 25]. https://namsdl.org/topics/pdmp/?fwp_pdmpsub=pdmp_access&fwp_document_source=namsdl

- 12.Kreiner P, Nikitin R, Shields TP. Bureau of Justice Assistance Prescription Drug Monitoring Program performance measures report: January 2009 through June 2012. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2014. April 4 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/Resources/BJA%20PDMP%20Performance%20Measures%20Report%20Jan%202009%20to%20June%202012%20FInal_with%20feedback.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. PDMP prescriber use mandates: characteristics, current status, and outcomes in selected states [Internet]. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2016. May [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/Resources/Briefing_on_mandates_3rd_revision_A.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. Briefing on PDMP effectiveness [Internet]. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2014. September [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/Resources/Briefing%20on%20PDMP%20Effectiveness%203rd%20revision.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. Mandating PDMP participation by medical providers: current status and experience in selected states [Internet]. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2014. February [cited 2019 Apr 25]. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/247134.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark T, Eadie J, Kreiner P, Strickler G. Prescription drug monitoring programs: an assessment of the evidence for best practices [Internet]. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2012. September 20 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/0001/pdmp_update_1312013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutkow L, Turner L, Lucas E, Hwang C, Alexander GC. Most primary care physicians are aware of prescription drug monitoring programs, but many find the data difficult to access. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2015. March 1;34(3):484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brady JE, Wunsch H, DiMaggio C, Lang BH, Giglio J, Li G. Prescription drug monitoring and dispensing of prescription opioids. Public Health Reports. 2014. March;129(2):139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delcher C, Wagenaar AC, Goldberger BA, Cook RL, Maldonado-Molina MM. Abrupt decline in oxycodone-caused mortality after implementation of Florida’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015. May 1;150:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishman SM, Papazian JS, Gonzalez S, Riches PS, Gilson A. Regulating opioid prescribing through prescription monitoring programs: Balancing drug diversion and treatment of pain. Pain Medicine. 2004. September 1;5(3):309–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gugelmann HM, Perrone J. Can prescription drug monitoring programs help limit opioid abuse?. JAMA. 2011. November 23;306(20):2258–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, et al. Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse?. Pain Medicine. 2012. March 1;13(3):434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, Webster DW, Stuart EA, Alexander GC. Effect of Florida’s prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill laws on opioid prescribing and use. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015. October 1;175(10):1642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haffajee RL, Jena AB, Weiner SG. Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programs. JAMA. 2015. March 3;313(9):891–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman PR, Goodin A, Troske S, Talbert J. Kentucky House Bill 1 impact evaluation [Internet]. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky; 2015. March 26 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.khpi.org/dwnlds/2015/KentuckyHB1ImpactStudyReport03262015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reilly C, Lawal S. Mapping Prescription Drug Monitoring Program enrollment and use: state-by-state data show prescriber utilization patterns [Internet]. Philadelphia, PA: The Pew Charitable Trusts; 2016. September 1 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/analysis/2016/09/01/mapping-prescription-drug-monitoring-program-enrollment-and-use [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuehn BM. FDA committee: more restrictions needed on hydrocodone combination products. JAMA. 2013. March 6;309(9):862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 29.Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2010. October 1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing Difference in Difference Studies: Best Practices for Public Health Policy Research. Annual Review of Public Health. 2018. April 1;39:453–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge JM. What are we weighting for?. Journal of Human Resources. 2015. March 31;50(2):301–16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates?. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2004. February 1;119(1):249–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchmueller TC, Carey C. The effect of prescription drug monitoring programs on opioid utilization in Medicare. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2018. February;10(1):77–112. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haffajee RL, Mello MM, Zhang F, Zaslavsky AM, Larochelle MR, Wharam JF. Four states with robust prescription drug monitoring programs reduced opioid dosages. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2018. June 1;37(6):964–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao Y, Wen K, Johnson P, Jeng PJ, Meisel ZF, Schackman BR. Assessing The Impact Of State Policies For Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs On High-Risk Opioid Prescriptions. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2018. October 1;37(10):1596–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Cai R. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003–2013. JAMA. 2015. October;314(14):1468–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen H, Schackman BR, Aden B, Bao Y. States with prescription drug monitoring mandates saw a reduction in opioids prescribed to Medicaid enrollees. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2017. April 1;36(4):733–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Abuse-deterrent formulations and the prescription opioid abuse epidemic in the United States: lessons learned from OxyContin. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015. May 1;72(5):424–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larochelle MR, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. Rates of opioid dispensing and overdose after introduction of abuse-deterrent extended-release oxycodone and withdrawal of propoxyphene. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015. June 1;175(6):978–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam MM, McRae IS. An inevitable wave of prescription drug monitoring programs in the context of prescription opioids: pros, cons and tensions. BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2014. December;15(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Office of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. 2013 prescription monitoring program survey results [Internet]. Augusta, ME: Maine Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [cited 2019 Apr 25]. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/samhs/osa/pubs/data/2013/PMPSurveyResultsFINALJul2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Q, Larochelle MR, Weaver DT, Lietz AP, Mueller PP, Mercaldo S, et al. Prevention of Prescription Opioid Misuse and Projected Overdose Deaths in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2019. February 1;2(2):e187621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the US opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2018. October;108(10):1394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saloner B. Commentary on Kertesz & Gordon (2019): Don’t abandon opioid prescription control efforts, reform them. Addiction. 2019. January;114(1):181–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.