Abstract

Over the past forty years, intramolecular hydroacylation has favored five-membered rings, in preference to four membered rings. Herein, we report a catalyst derived from earth abundant cobalt salts that enables preparation of cyclobutanones, with excellent regio-, diastereo-, and enantiocontrol, under mild conditions (2 mol% catalyst loading and as low as 50 °C).

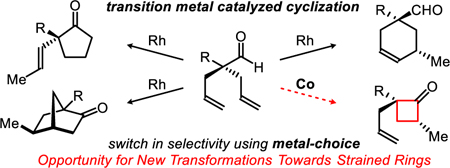

Graphical Abstract

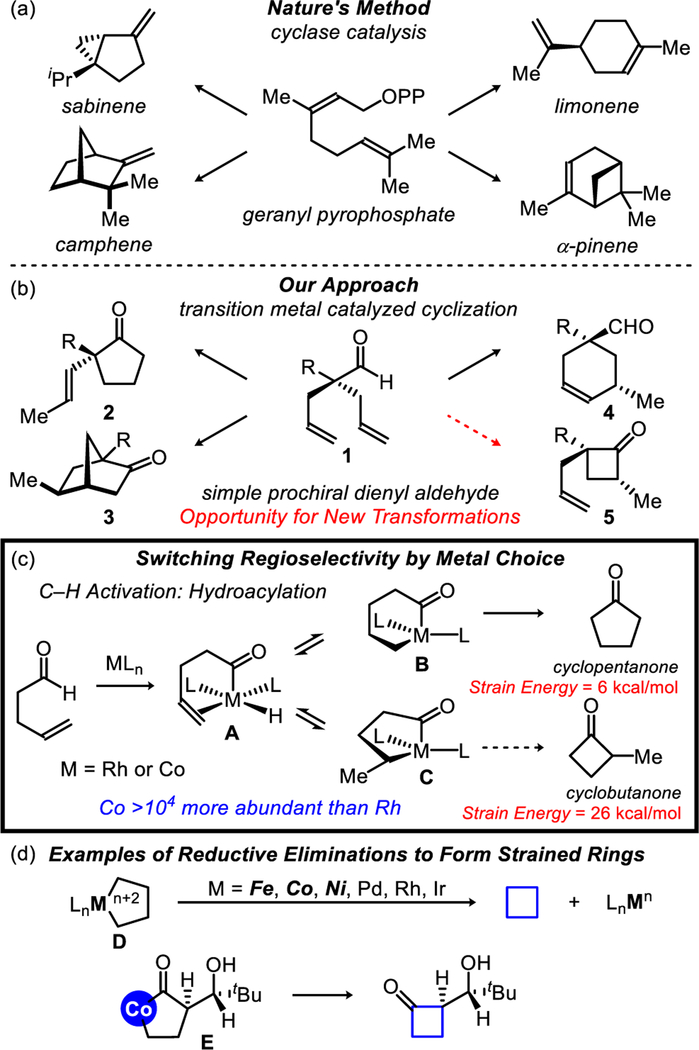

Metalloenzymes can transform simple olefins into a diverse array of cyclic natural products.1 For example, an achiral building block such as geranyl pyrophosphate undergoes ring-closing to generate a range of enantiopure terpenoids (e.g., sabinene, limonene, camphene, and pinene) (Figure 1a). Considering Nature’s ability to construct various rings via cyclases,2 we aim to diversify common building blocks into different cyclic isomers, with high enantioselectivity via synthetic catalysts.3 As an analogue to geranyl pyrophosphate, we designed a simple model, dienyl aldehyde (1), that can be accessed in one step from commercial materials.4 When using Rh-catalysis, we can transform this achiral aldehyde into the corresponding cyclopentanone (2), bicycloheptanone (3), or cyclohexenal (4) scaffold, by tuning the ligand scaffold (Figure 1b).3 Herein, we report a cobalt catalyst that enables ring closing to generate the four-membered ring (5) via enantioselective hydroacylation.

Figure 1.

Inspiration for cobalt-based cyclase mimic.

Hydroacylation5 (the addition of an aldehyde C–H bond across an olefin or alkyne) enables C–C bond formation with excellent atom economy.6 Most intramolecular variants provide exclusive access to cyclopentanones in preference to cyclobutanones.5 However, there are two exceptions, both of which use substrates bearing a methoxy-directing group under Rh-catalysis.7 Fu’s method achieves an enantioenriched mixture of four-and five-membered ketones via a parallel kinetic resolution. Aïssa observed a 12% yield of the four-membered ketone when performing a similar parallel kinetic resolution. Rather than relying on a precious metal or a kinetic resolution, we propose using a base-metal (Co) to overturn the usual regioselectivity of hydroacylation to favor the more strained ring.

Both Rh and Co are known to activate aldehyde C–H bonds through oxidative addition to form an acyl-metal-hydride intermediate A (Figure 1c).5,8 From this intermediate, olefin insertion results in an equilibrium mixture of the six- (B) and five-membered (C) metallacycles. In general, reductive elimination from B is thermodynamically and kinetically favored to generate the less strained cyclopentanone product.9 Moreover, achieving reductive elimination from a five-membered metallacycle (C) is challenging due to competitive endocyclic β-hydride elimination.10 By using first-row metals, however, C–C bond forming reductive eliminations from D to make small strained rings have been observed (Figure 1d).10–11 Most relevant to our study, Bergman characterized a cobaltacycle (E), which upon treatment with stoichiometric FeCl3, undergoes reductive elimination to form a cyclobutanone (Figure 1d).11e Encouraged by these breakthroughs, we set out to identify the first cobalt-catalyst capable of generating cyclobutanones.

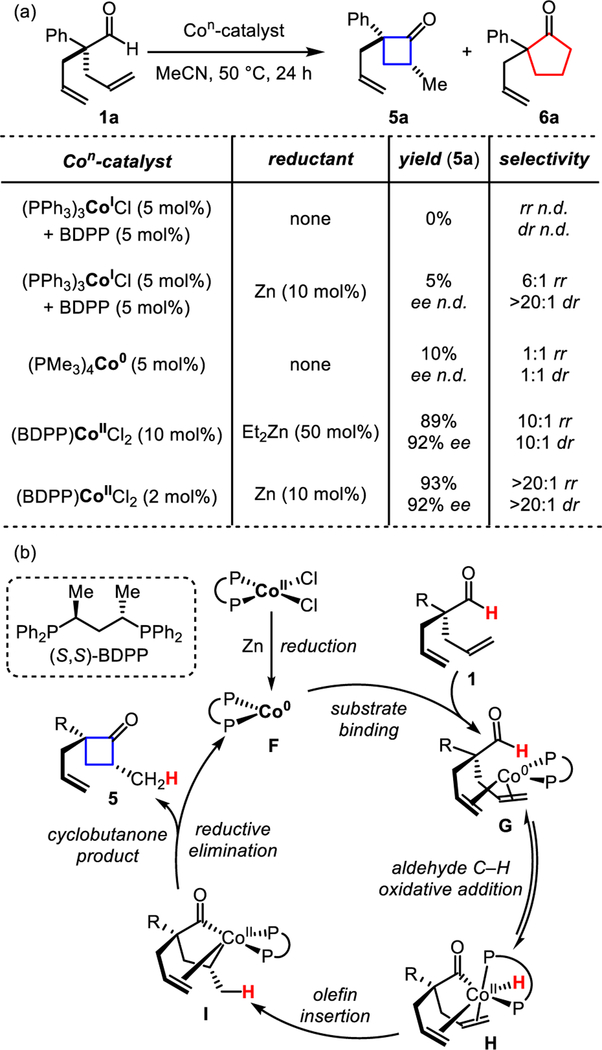

In our initial study, we found that commercially available Co(I)-catalysts, such as Co(PPh3)3Cl, results in no conversion to the desired cyclobutanone (Figure 2a). However, with Co(PPh3)3Cl, in the presence of a zinc reductant, we observe a 5% yield and 6:1 regioisomeric ratio (rr) of 5a: 6a. We postulate that the reductant transforms the Co(I)-complex into a Co(0)-catalyst critical for re-activity. Indeed, using a well-characterized, isolable Co(PMe3)4 (synthesized from CoCl2, magnesium, and trimethylphosphine) results in a mixture of 5a and 6a in 1:1 rr in 10% yield. Switching to a CoCl2/reductant system12, as a precursor for Co(0), enabled rapid evaluation of a range of chiral phosphine ligands.13 Under these conditions, we identified a chiral ligand, (S,S)-2,4-bis(diphe-nylphosphino)pentane (BDPP), that promotes the formation of 5a in preference to 6a. Cyclization with a catalyst loading of 10 mol% using diethyl zinc as the reducing agent gave promising selectivities (10:1 dr, 10:1 rr). Moreover, by desymmetrization, we access these motifs with 92% ee using this chiral bidentate phosphine ligand. On the basis of 1H NMR studies, we observe evolution of ethylene and ethane gas when using diethyl zinc. This observation is consistent with formation of a Co(0)-species.14 The catalyst loading can be lowered to 2 mol% when switching to activated zinc metal as a stronger reducing agent. The use of activated zinc improves reactivity (from 24 hours to 4 hours) and improves selectivities (from 10:1 dr and rr to >20:1 dr and rr) when using 10 mol% of the catalyst.

Figure 2.

Identifying catalyst for cyclobutanones.

Related protocols for Co-hydroacylation have been proposed to occur through both Co(0)/Co(II) and Co(I)/Co(III) catalytic cycles.8b-e While both are feasible, on the basis of our results, we propose this cyclization occurs by initial reduction of Co(II)-chloride to a Co(0)-complex (F), with activated zinc or diethyl zinc (Figure 2b). The Co(0)-catalyst then binds to the substrate (1) to form complex (G) prior to aldehyde C–H bond activation by oxidative addition. The acyl-Co-hydride intermediate (H) can isomerize by olefin insertion into the metal-hydride bond to forge the five-membered metallacycle (I). From here, reductive elimination forms the C–C bond to construct the strained ring (5).

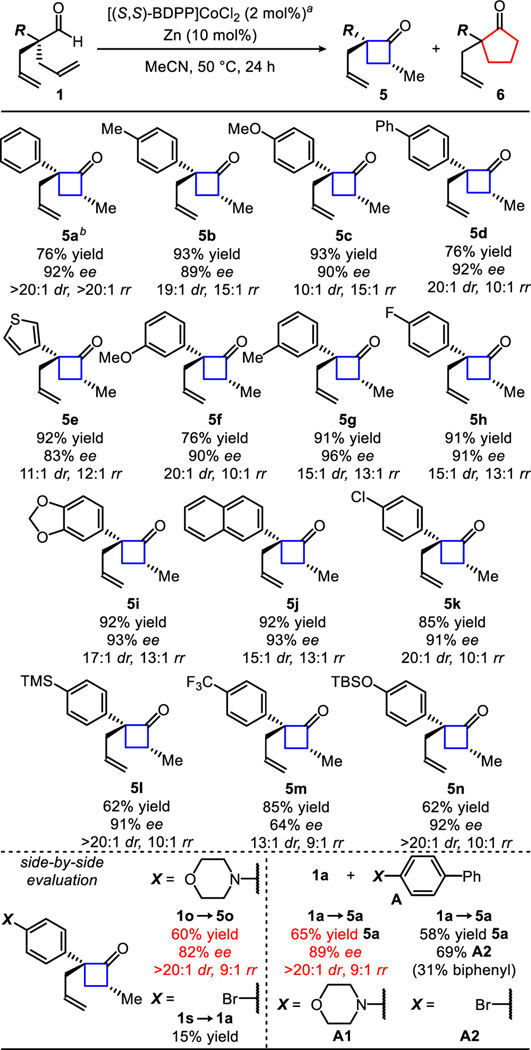

Under these mild conditions, a variety of α-aryl dienylaldehydes undergo isomerization to the corresponding cyclobutanones (Table 1). Dienylaldehydes bearing electron-rich α-aromatic groups (alkyls, ethers, acetals, and alcohols) ring close in good yields and selectivities (76–93% yields, >89% ee, >10:1 dr, >10:1 rr). Substrates with electron-poor α-aromatic groups (F, Cl, and CF3) also cyclize (91–85% yield, >64% ee, >13:1 dr, and >9:1 rr) albeit with lower enantioselectivities. Heteroaryl thiophene, silylated phenol, and amine substrates are well tolerated (60–92% yield, 82–95% ee, >11:1 dr, >9:1 rr). Of note, cyclobutanone 5a was generated on gram scale without impact on selectivity.

Table 1.

Synthesis of enantioenriched cyclobutanones.

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), [(S,S)-BDPP]CoCl2 (2 mol%), zinc (10 mol%), MeCN (0.5 mL), 50 °C, 24 h.

Gram-scale reaction (1a 6.40 mmol; [(S,S)-BDPP]CoCl2 (0.128 mmol, 2 mol%), zinc (0.640 mmol, 10 mol%), MeCN (32 mL, 0.2M), 50 °C, 24 h).

Robustness evaluation: Identical conditions above (a) + A [additive] (0.1 mmol, 1 equiv.).

Isolated yields of 5. Diastereo- and regioisomeric ratio determined by GC-FID analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture. Enantioselectivies determined by SFC analysis of the purified ketone.

We imagined that an aryl group bearing a range of functional groups could be tolerated in this transformation. To probe this idea, we performed a functional group compatibility test.15 We added an equivalent amount of various additives (e.g., pyridine, phenol, amines, etc.) with aldehyde (1a) under otherwise standard conditions.16 The cyclization to cyclobutanone (5a) occurs smoothly in the presence of heterocycles such as pyridines and indoles. Additives containing polar protic functional groups such as phenols, ani-lines, and amides as well as other carbonyl-containing additives such as aldehydes, ketones, esters, and amides had little effect on the transformation. The robustness screen provides a general guideline to the selectivities and to the types of functional groups tolerated in our reaction, 15 although selectivities can vary depending on where the functional group is attached. For example, we found that the addition of morpholine additive (A1) yielded 5a in 65% yield and 89% ee. We prepared the analogous morpholine containing substrate (1o) and performed the cyclization to provide cyclobutanone (5o) in similar yield but slightly lower ee.17 In contrast, an aryl-bromide containing additive (A2) and 4-bromodienyl aldehyde (1s) both underwent debromination to form biphenyl and 1a, respectively. Our cyclization proceeds well in the presence of known radical inhibitors such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT)18, 9,10-dihydroanthracene (DHA)19, and 1,1-diphenylethylene (DPE) (84% yield, 93% ee, >20:1 dr, 7:1 rr, with 94% additive recovered). The use of TEMPO as an additive inhibited reactivity presumably acting as an oxidant as well as a ligand on Co.20

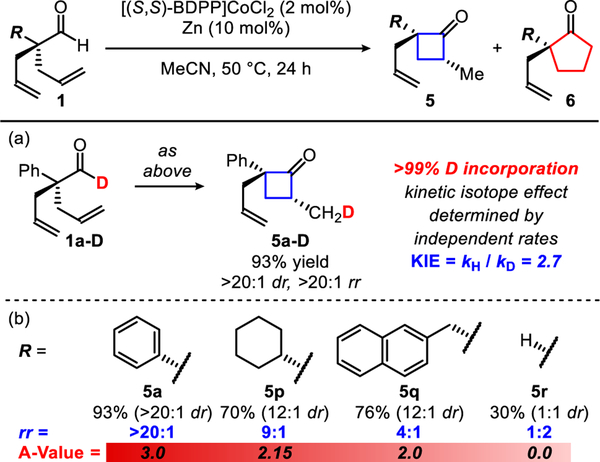

When using deuterium-labeled aldehyde 1a-D, we observe full incorporation of the deuteride into the α-methyl position of the cyclobutanone product 5a-D (Figure 3a). This isotopic labeling study provides results consistent with our proposed mechanism (Figure 2b). When comparing the measured initial rates of two parallel re-actions between the protio-aldehyde (1a) and deuterio-aldehyde (1a-D), we observe a primary kinetic isotope effect of 2.7 (KIE = 2.7). When monitoring the reaction with 1a-D as the substrate, no deuterium scrambling in the product or the starting material was observed. The primary KIE alongside a lack of deuterium scrambling likely points to aldehyde C–H bond activation or olefin insertion into the Co–H bond as the turnover-limiting step.

Figure 3.

Reaction evaluation of dienyl aldehyde.

By studying the scope of this cyclization, we found that regioisomeric ratio (rr) of 5:6 is influenced by the α-position of the aldehyde (Figure 3b). Higher selectivity for the four-membered versus five-membered ketone is observed with increasing size of the α-substituent (R in Figure 3). The highest selectivity is observed with phenyl dienylaldehyde 1a (>20:1 rr, A-value = 3.0 for R = Ph) and the lowest selectivity is observed with dienylaldehyde 1r (1:2 rr, A-value = 0.0 for R = H).21 This results suggests that olefin in-sertion is turnover-limiting and favors formation of the five-membered metallacycle. We reason that the increased steric crowding around the metal center promotes formation of the five-membered metallacycle C over the six-membered metallacycle B.22 This is due to bond-angle compression making the five-membered metallacycle C more thermodynamically stable and kinetically accessible. Thus, despite ring-strain, reductive elimination to form the four-membered ring is not turnover-limiting.

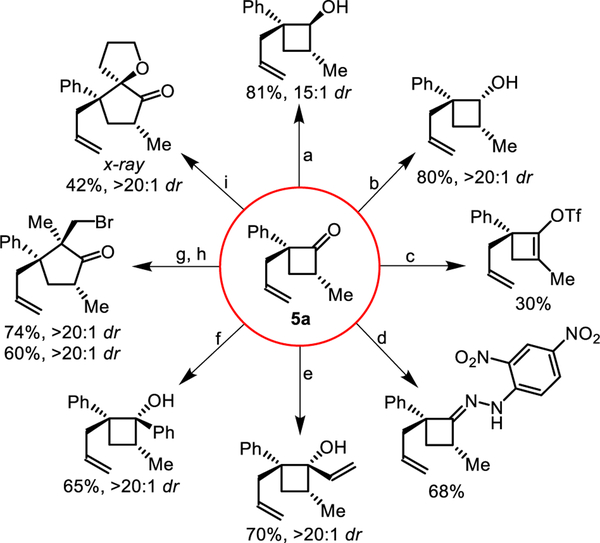

The newly formed stereocenters in our cyclobutanone scaffold can be put to use in a number of stereoselective reactions to build different structures (Figure 4). The reduction to the secondary alcohol can be controlled depending on choice of the reductant. DIBAL–H adds from the more sterically hindered face (a), while L-Selectride adds from the less hindered face (b). This strained ketone can be converted to an enol-triflate suitable for cross-coupling reactions (c). Strained ketimines can be prepared by condensation with 2,4-dinitrohydrazine (d). New C–C bonds can be generated in a highly diastereoselective fashion (>20:1) by using vinyl- (e) or phenyl-Grignard (f) addition to generate the tertiary cyclobutanols. Taking advantage of the ring-strain23, the cyclobutanones can undergo ring-expansion to enantioenriched cyclopentanones with vicinal all-carbon quaternary centers by addition of isoproprenyl-magnesium bromide (g) followed by electrophilic bromination (h). Similarly, the addition of a lithiated-dihydrofuran followed by treatment with mild acid results in a one-carbon ring expansion to form a cyclopentanone (i). This spirocyclopentanone was crystalline and a molecular structure was unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography along with assignment of the absolute stereochemistry of the cyclobutanone products 5a–o by analogy. Although not depicted, the unreacted allyl-moiety could also be used as an additional functional handle.

Figure 4. Derivatization of cyclobutanone 5a.

(a) DIBAL–H; (b), L-Selectride; (c) LiHMDS, Comins’ reagent; (d) 2,4-dinitrophenyl-hydrazine, sulfuric acid; (e) vinylmagnesium bromide; (f) phenyl-magnesium bromide; (g) isopropenylmagnesium bromide; (h) N-bromosuccinimide; (i) 1,2-dihydrofuran, n-BuLi, then silica chromatography.

While cycloadditions are typically used to make four-membered rings, cyclobutanones bearing α-quaternary carbons are challenging to access, especially with high enantiocontrol.24 Our approach features a Co-catalyst that can isomerize a simple, prochiral dienyl-aldehyde into cyclobutanones bearing chiral α-quaternary carbon centers, with excellent diastereo-, regio-, and enantiocontrol. Mechanistic studies suggest a pathway involving a Co(0)/Co(II) cycle that is triggered by C–H bond activation. A switch from a precious metal to an abundant base-metal enables a shift in the construction of strained rings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding provided by UC Irvine and the National Institutes of Health (GM105938). We are grateful to Eli Lilly for a Grantee Award. We thank Dr. Joseph W. Ziller and Jason R. Jones (UC Irvine) and Dr. Milan Gembicky (UC San Diego) for X-ray crystallographic analysis. We also thank Professor Yang & her laboratory for their assistance in obtaining UV-Vis absorption spectra.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds (PDF)

Crystallographic data (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Dewick PM In Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach; Wiley: West Sussex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Baran PS; Maimone TJ; Richter JM Nature 2007, 446, 404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Maimone TJ; Baran PS Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Park J-W; Kou KGM; Kim DK; Dong VM Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 4479; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Park J-W; Chen Z; Dong VM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jiang G; List B Adv. Synth. Catal 2011, 353, 1667. [Google Scholar]

- (5).For a review on hydroacylation see: Willis MC. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Newhouse T; Baran PS; Hoffmann RW Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 3010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM Science 1991, 254, 1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Yip SYY; Aïssa C Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 6870; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka K; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Murphy SK; Park JW; Cruz FA; Dong VM Science 2015, 347, 56; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lenges CP; Brookhart MJ Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 3165; [Google Scholar]; (c) Yang J; Seto YW; Yoshikai N ACS Catal 2015, 5, 3054; [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang J; Yoshikai NJ Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16748; [Google Scholar]; (e) Vinogradov MG; Tuzikov AB; Nikishin GI; Shelimov BN; Kazansky VB J. Organomet. Chem 1988, 348, 123. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hyatt IFD; Anderson HK; Morehead AT; Sargent AL Organomet. 2008, 27, 135. [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) For examples of competing b-hydride eliminations from 5-membered metallocycles see: Schmidt VA; Hoyt JM; Margulieux GW; Chirik PJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 7903; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Grubbs RH; Miyashita AJ Am. Chem. Soc 1978, 100, 1300. [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) For examples of reductive eliminations from 5-membered metallocycle see:Hoyt JM; Schmidt VA; Tondreau AM; Chirik PJ Science 2015, 349, 960; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Binger P; Doyle MJ J. Organomet. Chem 1978, 162, 195; [Google Scholar]; (c) Murakami M; Amii H; Ito Y Nature 1994, 370, 540; [Google Scholar]; (d) Camasso NM; Sanford MS Science 2015, 347, 1218; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Theopold KH; Becker PN; Bergman RG J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 5250; [Google Scholar]; (f) Chao KC; Rayabarapu DK; Wang C-C; Cheng C-HJ Org. Chem 2001, 66, 8804; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hilt G; Paul A; Treutwein J Org. Lett 2010, 12, 1536; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Treutwein J; Hilt G Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 6811; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Abulimiti A; Nishimura A; Ohashi M; Ogoshi S Chemistry Letters 2013, 42, 904; [Google Scholar]; (j) Kumar R; Tamai E; Ohnishi A; Nishimura A; Hoshimoto Y; Ohashi M; Ogoshi S Synthesis 2016, 48, 2789; [Google Scholar]; (k) Nishimura A; Tamai E; Ohashi M; Ogoshi S Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 6613; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Ohashi M; Ueda Y; Ogoshi S Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 2435; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Hu J; Yang Q; Yu L; Xu J; Liu S; Huang C; Wang L; Zhou Y; Fan B Org. Biomol. Chem 2013, 11, 2294; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) McNally A; Haffemayer B; Collins BSL; Gaunt MJ Nature 2014, 510, 129; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Willcox D; Chappell BGN; Hogg KF; Calleja J; Smalley AP; Gaunt MJ Science 2016, 354, 851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Friedfeld MR; Margulieux GW; Schaefer BA; Chirik PJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 13178; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Friedfeld MR; Shevlin M; Hoyt JM; Krska SW; Tudge MT; Chirik PJ Science 2013, 342, 1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).For a comprehensive list of ligands evaluated see Supporting Information.

- (14).For a proposed mechanism, 1H NMR, and UV-Vis absorption spectra data for the formation of Co(0)-species using diethyl zinc, see Supporting Information.

- (15).(a) Collins KD; Glorius F Nat. Chem 2013, 5, 597; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collins KD; Rühling A; Glorius F Nat. Protocols 2014, 9, 1348; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Collins KD; Glorius F Acc. Chem. Rev 2015, 48, 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).For a comprehensive list of functional groups evaluated and reaction outcomes under standard reaction conditions with 1a, see Supporting Information.

- (17).(a) For examples of robustness screens with reactions containing enantioselectivities see: Schmidt J; Choi J; Liu AT; Slusarczyk M; Fu GC Science 2016, 354, 1265; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Janssen-Müller D; Schedler M; Fleige M; Daniliuc CG; Glorius F Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 12492; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yetra SR; Mondal S; Mukherjee S; Gonnade RG; Biju AT Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ross L; Barclay C; Vinqvist MR In PATAI’S Chemistry of Functional Groups; Wiley: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bass KC In Organic Syntheses; Wiley: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Semproni SP; Milsmann C; Chirik PJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Anslyn EV; Dougherty DA Modern Physical Organic Chemistry; University Science Books: Sausalito, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hartwig JF Organotranisition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Sausalito, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Seiser T; Saget T; Tran DN; Cramer N Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 7740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) Xu Y; Conner ML; Brown MK Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 11918; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Du J; Skubi KL; Schultz DM; Yoon TP Science 2014, 344, 392; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Douglas CJ; Overman LE Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 5363; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Quasdorf KW; Overman LE Nature 2014, 516, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.