Abstract

Introduction

The Woven EndoBridge Intrasaccular Therapy (WEB-IT) Study is a pivotal, prospective, single-arm, investigational device exemption study designed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the WEB device for the treatment of wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms.

Methods

One-hundred and fifty patients with wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms were enrolled at 21 US and six international centers. Angiograms from the index procedure, and 6-month and 1-year follow-up visits were all reviewed by a core laboratory. All adverse events were reviewed and adjudicated by a clinical events adjudicator. A data monitoring committee provided oversight during the trial to ensure subject safety.

Results

One-hundred and forty-eight patients received the WEB implant. One (0.7%) primary safety event occurred during the study—a delayed ipsilateral parenchymal hemorrhage—on postoperative day 22. No primary safety events occurred after 30 days through 1 year. At the 12-month angiographic follow-up, 77/143 patients (53.8%) had complete aneurysm occlusion. Adequate occlusion was achieved in 121/143 (84.6%) subjects.

Conclusions

The prespecified safety and effectiveness endpoints for the aneurysms studied in the WEB-IT trial were met. The results of this trial suggest that the WEB device provides an option for patients with wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms that is as effective as currently available therapies and markedly safer.

Trial registration number

Keywords: aneurysm, blood flow, coil, device, magnetic resonance angiography

Introduction

Wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms (WNBAs) can be difficult to treat with either endovascular or open surgical methods. Complete exclusion of the aneurysm from the intracranial circulation without impeding flow through the origin of branch arteries can be technically challenging. A recent systematic review showed that published reports document a complete occlusion rate of 46.3% for all therapies, with prespecified safety endpoints being met in 18.7% of cases.1

The Woven EndoBridge (WEB) device is the first intrasaccular device developed specifically for the treatment of WNBAs.2 3 The first use of the WEB device was reported in 2011.4 Subsequently, the effectiveness and safety of the device has been evaluated in four European good clinical practice (GCP) studies.4–9 The WEB Intrasaccular Therapy (WEB-IT) Study is a pivotal, multicenter, prospective, single-arm, investigational device exemption trial designed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of this device for the treatment of WNBAs. WEB-IT is the first adjudicated trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of any treatment for WNBAs. The trial is also the first US premarket approval trial of an intrasaccular aneurysm device.

Methods

Study design

The WEB-IT Study is a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, interventional study conducted at 21 US and six international centers. The study enrolled 150 adults with WNBAs of the anterior and posterior intracranial circulations. The study protocol was approved by each center’s institutional review boards or by the review board assigned by the Turkish Ministry of Health, and all patients submitted written informed consent. The study was conducted under GCP and included independent adjudication of all adverse events. An independent core laboratory adjudicated effectiveness outcomes. All patient charts were externally monitored with 100% source document verification. A clinical events adjudicator evaluated and standardized reporting of events in compliance with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities reporting standards. A data monitoring committee conducted regularly scheduled study safety reviews.

No roll-in cases were permitted in the USA before the enrollment of patients in WEB-IT. Therefore, the trial cases represent the first clinical experience that US physicians had with the device. A training program, which included hands-on experience using a lifelike simulator, was used.10 This program helped to familiarize investigators with the device’s characteristics, sizing, and deployment. In some early cases, patient-specific replicated models were used.

Required aneurysm characteristics were

Ruptured or unruptured

Saccular in shape

Located at the basilar apex (BA), middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation, internal carotid artery terminus, or anterior communicating artery complex

Dome-to-neck ratio ≥1

Wide-neck intracranial aneurysm with neck size ≥4 mm or dome-to-neck ratio <2

Diameter appropriate for treatment with the WEB device according to the device instructions for use

Patients with ruptured aneurysms were required to be neurologically stable with a Hunt-Hess score of I or II. Key exclusion criteria included vascular tortuosity or morphology that could preclude safe access and support during treatment with WEB and a modified Rankin Scale score of ≥2 at baseline or before rupture.

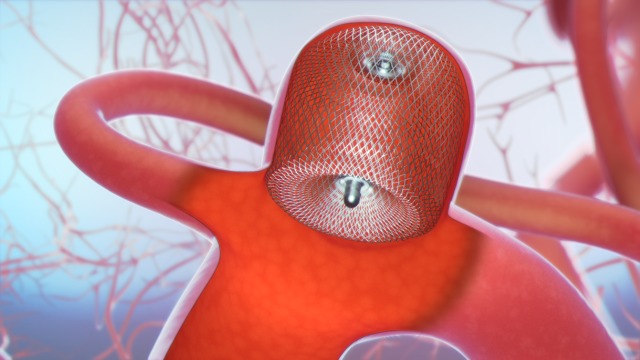

Device characteristics

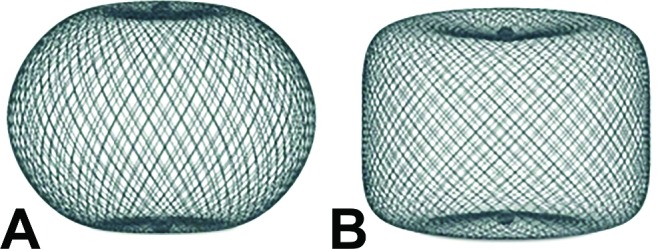

The WEB Aneurysm Embolization System (Sequent Medical, Inc, Aliso Viejo, California, USA) consists of a family of self-expanding embolization implants developed specifically for the treatment of WNBAs. The WEB single-layer sphere and WEB single-layer models are composed of single layers of braided nitinol/platinum wires (figure 1). The braids are joined at the proximal and distal ends of the device by radiopaque platinum markers. The implant is attached to a flexible delivery wire. Detachment of the implant is electrothermal, which is similar to several other neurovascular implant delivery systems. WEB devices ranging between 4×3 mm and 11×9 mm—and delivered through VIA 21, 27, and 33 microcatheters (Sequent Medical, Inc, Aliso Viejo, California, USA)—were available for use within the WEB-IT protocol.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the WEB single-layer sphere (A) and the WEB single layer (B) shapes. Sizes range from 4×3 mm to 11×9 mm. The devices are braided composites made from nitinol and platinum that are highly conformable and visible on fluoroscopy.

Procedures

All enrolled patients underwent a standard neuroendovascular procedure using a triaxial approach with the intent of delivering and implanting a WEB device into the index aneurysm. Antiplatelet therapy was recommended but was not required according to the study protocol.11 Antiplatelet medication used during the study was recorded at each study visit. The regimens used are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Antiplatelet status of patients in the US WEB-IT Trial

| Visit | Antiplatelet therapy, % (n/N) | ||

| Dual | Single | None | |

| Baseline | 12.7 (19/150) | 14.7 (22/150) | 72.7 (109/150) |

| Procedure | 69.3 (104/150) | 27.3 (41/150) | 3.3 (5/150) |

| 30 Days | 31.3 (47/150) | 56.0 (84/150) | 12.7 (19/150) |

| 6 Months | 11.3 (16/142) | 62.7 (89/142) | 26.1 (37/142) |

| 12 Months | 7.0 (10/143) | 41.3 (59/143) | 51.7 (74/143) |

Patients were considered ‘enrolled in WEB-IT’ with the intention-to-treat when the WEB device was introduced into the microcatheter during the procedure. Two-dimensional (2D) and 3-dimensional (3D) digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed to confirm the final device position. Inability to deploy a WEB device and the use of implanted adjunctive devices (ie, coils or stents) were considered effectiveness failures. Clinical follow-up was conducted at 30 days, 6 months, 1 year, and annually up to 5 years. Follow-up 2D and 3D DSA was performed at 6 months and 1 year. This report includes an evaluation of effectiveness at 1 year and all safety events occurring through 1 year.

Study endpoints

Thirty-day safety data for the WEB-IT Study have been published previously.12 Per protocol, safety, and effectiveness were assessed at the 1-year follow-up. The study’s primary effectiveness endpoint is the proportion of patients with complete aneurysm occlusion without re-treatment, recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage, or significant parent artery stenosis (defined as >50% stenosis) at 1 year after treatment. Effectiveness endpoints were evaluated by a core laboratory using the validated WEB Occlusion Scale. Complete occlusion included WEB Occlusion Scale grade A (complete occlusion) or B (complete occlusion with marker recess).13 14 The study’s primary safety endpoint is the proportion of patients with primary safety events (PSEs), which includes death from any non-accidental cause or any major stroke (defined as an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke resulting in an increase of ≥4 points on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and persisting for 7 days after the procedure) within the first 30 days after treatment, or a major ipsilateral stroke or neurologic death from day 31 to 1 year after treatment.

Results

Patient allocation

One-hundred and fifty patients were enrolled into the WEB-IT Study. Of these, 148 underwent successful implantation of the study device. All 150 enrolled patients were available for 30-day follow-up. Those who were not treated with the WEB device were only followed up through 30 days according to the protocol. Of the 148 patients available for the 6-month follow-up, 142 completed the visit. One patient refused further follow-up after the 6-month window and was withdrawn from the study, leaving 147 patients eligible for the 12-month follow-up. Of the 147 patients eligible at 1 year, 147 were followed up clinically and 143 underwent follow-up imaging with DSA (table 2).

Table 2.

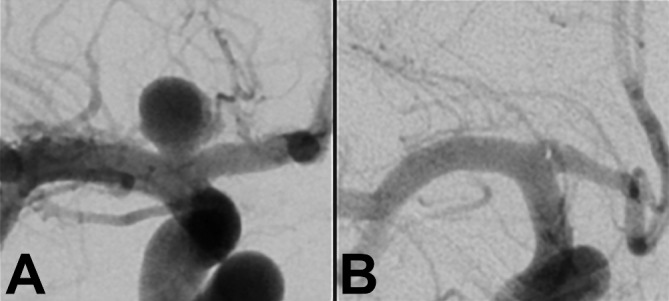

The WEB-IT angiographic scale

| WEB-IT scale | Definition | 1-Year angiographic outcome descriptions | 1-Year angiographic schematics | 1-Year angiographic WEB-IT examples |

| Complete occlusion | No contrast in contact with intracranial aneurysm neck or with wall of intracranial aneurysm sac | WEB-IT effectiveness endpoint |

|

|

| Residual neck | Some contrast in contact with intracranial aneurysm neck but no contrast in contact with wall of intracranial aneurysm sac or inside the WEB device | Adequately occluded patients when combined with completely occluded patients |

|

|

| Residual aneurysm | Apparent contrast in contact with intracranial aneurysm sac or inside the WEB device | Patients who may require re-treatment |

|

|

| The WEB-IT angiographic scale is described with definitions. This scale was used by the core laboratory for evaluation of angiographic follow-up at 1 year. Illustrations depict three separate basilar apex wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms and 1-year follow-up imaging from the trial. | ||||

Patient demographics, aneurysm characteristics, procedural details, and periprocedural safety results at 30 days were reported previously.12

Primary effectiveness endpoint

The primary effectiveness endpoint was defined as the proportion of subjects with complete aneurysm occlusion without re-treatment, recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage, and without significant parent artery stenosis at 1 year after treatment in the intention-to-treat population (figures 2–5). The primary effectiveness endpoint with prespecified imputations performed for the subjects without angiographic follow-up was 54.8% (SE 4.1).

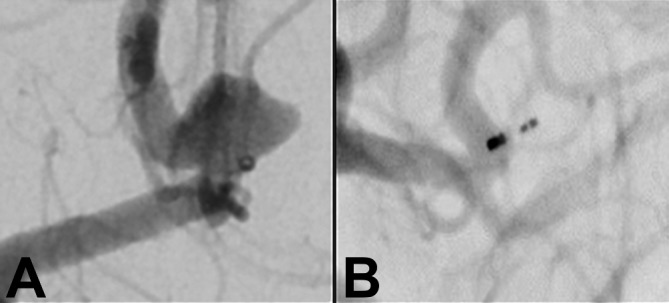

Figure 2.

(A) Unruptured internal carotid terminus aneurysm measuring 7 mm in maximal dimension with a 4 mm neck before treatment. (B) The same internal carotid terminus aneurysm on follow-up imaging at 1 year, showing complete occlusion.

Figure 3.

(A) Unruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm measuring 4.5 mm in maximal dimension with a 4.1 mm neck before treatment. (B) The same anterior communicating artery aneurysm on follow-up imaging at 1 year, showing complete occlusion.

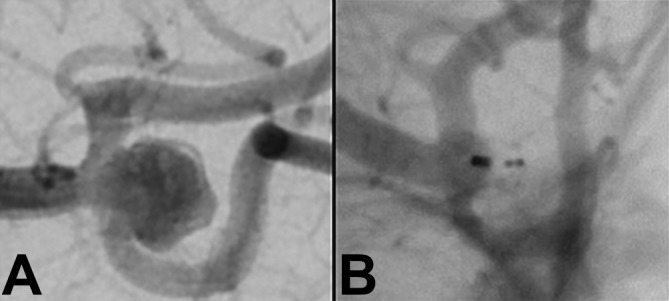

Figure 4.

(A) Unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysm measuring 7 mm in maximal dimension with a 5.5 mm neck before treatment. (B) The same middle cerebral artery aneurysm on follow-up imaging at 1 year, showing complete occlusion.

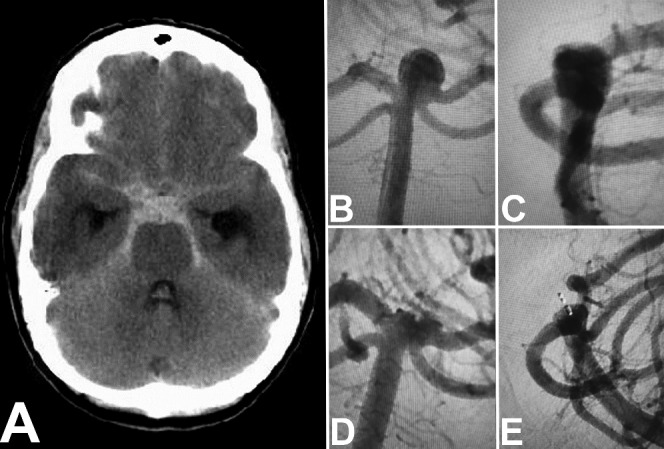

Figure 5.

Non-contrast head CT (A) showing diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage and hydrocephalus. Anteroposterior (B) and lateral (C) imaging of a ruptured basilar apex aneurysm found in this patient measuring 3.3 mm in height and 4.7 mm in neck size before treatment. The same basilar apex on follow-up imaging—anteroposterior (D) and lateral (E)—at 1 year, showing incomplete occlusion.

The rate of complete occlusion in patients in whom the WEB device procedure was completed and imaging follow-up was performed was 53.8% (77/143). Adequate occlusion was defined as either complete occlusion or residual neck. This analysis was performed only in the case population with imaging follow-up. Adequate occlusion was achieved in 84.6% of subjects (121/143). The analyses of subgroups, including gender, race, ethnicity, sac width (<8 mm, ≥8 mm), aneurysm rupture status, aneurysm location, site experience, and diameter of the WEB device used, all suggest no difference in the rate of achievement of either complete or adequate occlusion.

Progression and stability of aneurysm occlusion

Changes in aneurysm occlusion were determined using a simple ‘same-better-worse’ scale. Any increase in aneurysm occlusion was graded as ‘better’ and any decrease was graded as ‘worse.’ Any worsening in angiographic appearance was categorized as a recurrence.

In comparison with the immediate post-treatment angiogram, most aneurysms showed substantial progressive occlusion by 6 months—5.0% (7/141) were worse, 3.5% (5/141) were the same, and 91.5% (129/141) were better. Between 6 and 12 months, most aneurysms were either stable or continued to improve in occlusion grade. Among patients with both 6- and 12-month angiograms (excluding six subjects who underwent re-treatment), when compared with the 6-month angiogram, 11.5% (15/131) were worse, 79.4% (104/131) were the same, and 9.2% (12/131) were better at 12 months. The majority of subjects with recanalization or regrowth between 6 and 12 months declined by only a few percentage points. Ten subjects who went from 100% occlusion at 6 months declined to 98% (n=3), 95% (n=5), and 90% (n=2) at 12 months.

Parent artery stenosis

The development of a significant (>50%) parent artery stenosis was not observed in any patient treated with the WEB device. A single subject with a residual aneurysm had a documented parent artery stenosis on the 12-month angiogram within a stent that had been placed during re-treatment after the 6-month angiogram.

Re-treatment

During the 12-month study period, 5.6% (8/143) underwent or had planned target aneurysm re-treatment. One subject was re-treated with coils alone, four were re-treated with stent-assisted coiling, and three were re-treated with flow diversion. The cases of all eight re-treated subjects were considered failures for the primary effectiveness endpoint. An additional six patients, all of whom were categorized as effectiveness failures based on their 12-month angiogram results, underwent electively scheduled re-treatments within the ensuing 6 months. When these additional six patients are categorized within the overall ‘re-treatment’ cohort, the re-treatment rate increased to 9.8% (14/143).

Recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage

No recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhages occurred during the study among the nine subjects who presented with ruptured aneurysms at baseline. No spontaneous postprocedural subarachnoid hemorrhages were seen in any patient through 1 year.

Primary safety endpoint

No PSEs occurred after 30 days through 1 year. Only 1 (1/148, 0.7%) PSE occurred during the study—a delayed ipsilateral parenchymal hemorrhage, on postoperative day 22. In the two patients who were enrolled but not treated with WEB, no safety events were seen through the protocol-defined 30 day follow-up period.

Other serious neurological events after 30 days

No deaths occurred through the entire 12-month study period. Additionally, no patient had an ipsilateral stroke between day 31 and day 365 after treatment. There were no serious adverse events attributed to either the device or procedure between day 31 and day 365.

Six patients had unrelated serious neurological events after 30 days—one ischemic stroke, one intracranial hemorrhage, one seizure, and three transient ischemic attacks. In four of these subjects, these events resolved without any sequelae. One subject who underwent a reintervention with a Pipeline embolization device on day 203 subsequently developed recurrent transient ischemic attacks, which were adjudicated as ‘ongoing’ at the time of the 12-month clinical follow-up. One subject experienced two ischemic stroke events (on day 12 and day 72) related to pre-existing cerebrovascular disease and had persistent right leg weakness and gait instability at the 12-month follow-up.

Discussion

The final data from the Pivotal WEB-IT trial demonstrate that the WEB device, when used for the treatment of appropriately selected wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms (1) provides an effective means of achieving durable, adequate occlusion in most (~85%) cases, and (2) can be used with a high degree of procedural safety and with a low rate of major morbidity and mortality. In particular, no serious device- or procedure-related safety events were identified outside the 30-day periprocedural period and no deaths occurred during the 12-month study period.

Relative safety of the WEB device in comparison with other WNBA treatment strategies

The periprocedural safety of the WEB device has been previously described.12 The high safety profile documented for the WEB device for the treatment of ruptured WNBAs is important. The complication profile for stent-assisted coiling of ruptured WNBAs is not trivial and an endovascular treatment option that does not require dual antiplatelet medication fills an unmet clinical need.15 Although the number of patients (nine) with subarachnoid hemorrhage treated in this study was small, these patients had similar rates of adverse events and serious adverse events as the patients with an unruptured aneurysm within the study. Moreover, the 30-day results of the CLinical Assessment of WEB device in Ruptured aneurYSms (CLARYS) study have indicated high rates of procedural safety, with no intraprocedural or recurrent hemorrhages documented in 56 patients with ruptured aneurysms.11

In the present study, no postprocedural device, procedure-related serious adverse events or deaths were observed between days 31 and 365. This level of postprocedural safety is unparalleled for the treatment of WNBAs. Parent artery stenting has been associated with significant rates of postprocedural events, related to delayed in-stent stenosis or thrombosis, and hemorrhagic events related to dual antiplatelet therapy.16–19

Relative effectiveness of the WEB device in comparison with other strategies for treating WNBAs

The complete occlusion rates observed in WEB-IT compare favorably with predicate technologies. A recent meta-analysis reported a complete occlusion rate for wide-necked aneurysms (including WNBAs) of only 46% for both surgical and endovascular treatment strategies.1 Hetts et al reported levels of complete occlusion in the Matrix And Platinum Science (MAPS) trial for wide-necked aneurysms of 45.7% after stent-assisted coiling and 27.1% after coiling alone.18 It is important to note that both these studies included all wide-necked aneurysms. The subset of WNBAs typically has lower rates of complete occlusion than side-wall aneurysms, and it is likely that a specific analysis of the bifurcation aneurysms in these studies would have yielded lower rates of complete occlusion.

The BRANCH trial, which was a core laboratory adjudicated study of wide-necked MCA and BA aneurysms, reported a rate of complete occlusion of only 31% (95% lower confidence limit of 22%) after endovascular therapy.20 An analysis of the patient level data from the 153 aneurysms treated in the Low-profile Visible Intraluminal Support device (LVIS) trial yielded a cohort of 40 subjects who would have met inclusion criteria for the WEB-IT trial. Twenty-five of these 40 WNBAs (62.5%) demonstrated complete occlusion at the 12-month follow-up.21 Although the point estimate for complete occlusion was higher, the difference in this small number of patients did not reach significance (p=0.37) when compared directly with the WEB-IT (53.9%) population. Rates of neurological mortality and major morbidity in these LVIS-treated patients (7.6%) were considerably higher than those observed during the WEB-IT Study (0.7%). Moreover, the LVIS stent is relatively contraindicated in the presence of subarachnoid hemorrhage owing to the requirement for dual antiplatelet medication.

While the WEB device produced comparable levels of complete occlusion for WNBAs as other endovascular technology, additional progress is required. The reconstruction of bifurcation anatomy is considerably more difficult than for side-wall aneurysms. It is not surprising that the complete occlusion rates for WNBAs are inferior to those reported for side-wall aneurysms reconstructed with flow diverters.22–25

Adequate occlusion (ie, the composite of complete and near-complete occlusion) rates in WEB-IT exceeded 80%. Long-term data on the WEB device are lacking, but existing long-term data from endovascular coiling studies have indicated that adequate occlusion after endovascular therapy offers a very high level of protection from rupture and/or rerupture.26–30 These data are consistent with our observations in the WEB-IT Study and with three additional prospective studies that reported no delayed ruptures or reruptures of aneurysms treated with the WEB device, with more than 760 patient-years of follow-up to date.5 7 9

Durability of aneurysm occlusion with the WEB device

Aneurysm recurrence was observed in WEB-IT at a similar rate (~11%) to that reported in other studies evaluating the endovascular treatment of WNBAs. For example, Hetts et al reported recurrence rates of 21.4% and 50.8% for WNAs treated with stent-assisted coiling and coiling alone, respectively.30 Existing data from the aneurysm coiling literature indicate that while recurrence rates decline after 12 months, long-term surveillance is warranted.31 32 Of note, the WEB-IT patients will be followed up for 5 years and thus, long-term recurrence and re-treatment data will eventually be available for this cohort.

Aneurysm re-treatment (9.8%) in the WEB-IT Study was significant and similar to the rates seen in the existing literature for WNBAs after endovascular therapy. Re-treatment decisions were made by the individual patients and their physicians and no criteria for re-treatment were specified in the protocol. As thresholds for re-treatment vary broadly, direct comparisons are challenging.33 In the MAPS study, re-treatments were performed in 13.7% of wide-necked aneurysms treated with coils alone, and in 14.1% of those treated with stent-assisted coiling through 1 year.18 Similarly, the BRANCH investigators reported an 8.7% re-treatment rate for wide-necked MCA and BA aneurysms.20

Generalizability

The safety, effectiveness, and durability results observed in WEB-IT are concordant with the existing literature. Pierot et al reported the cumulative results for 168 patients treated within three prospective GCP, core laboratory adjudicated, externally monitored studies.7 These investigators reported a similarly high rate of periprocedural safety with 0% mortality and 3% morbidity (5/167) at 30 days. Late complications were also uncommon, with only one neurological mortality (0.7%, 1/153) and two patients with significant neurological morbidity (1.3%, 2/153) after 30 days. Rates of aneurysm occlusion at 12 months were strikingly similar to those observed in the WEB-IT trial: complete occlusion observed in 52.9% (81/153), neck remnant in 26.1% (40/153), and residual aneurysm in 20.9% (32/153).7 The re-treatment rate (6.3%) was also almost identical to that in WEB-IT.

Conclusion

The WEB device is an effective therapy for wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms. This device is an important tool for the treatment of WNBAs, particularly for patients in whom surgical clipping carries high risks and in patients with contraindications to antiplatelet therapies. We expect continued iterative improvement in intrasaccular flow diversion technologies. It is our hope that these improvements will result in higher rates of complete aneurysm occlusion and durability. The safety of this therapy significantly exceeds that demonstrated with other treatments for WNBAs.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the WEB single layer device.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr Andrew J. Gienapp (Neuroscience Institute, Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital and Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, USA) for copy editing and publication assistance. The investigators also recognize Ms Amy Walters for her integral role in the planning, design, and oversight of the WEB-IT and the European good clinical practice WEB studies. Without Ms Walters’ incredible work, this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors of this work met International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship and made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, critical revising, and final approval of this manuscript.

Funding: The WEB-IT Study was supported by Sequent Medical Inc, Aliso Viejo, California, USA.

Competing interests: The principal investigators for the WEB-IT trial received institutional salary support for study-related activities. Investigators in the WEB-IT trial also received payment for proctoring cases within the context of the trial. ASA is a consultant for Balt, Johnson and Johnson, Leica, Medtronic, Microvention, Penumbra, Scientia, Siemens, and Stryker; receives research support from Microvention, Penumbra, and Siemens; and is a shareholder in Bendit, Cerebrotech, Endostream, Magneto, Marblehead, Neurogami, Serenity, Synchron, Triad Medical and Vascular Simulations outside the submitted work. AM is a consultant for Microvention/Sequent, Stryker Neurovascular, and Cerus outside the submitted work. ALC is a consultant for Medtronic, Microvention, and Stryker Neurovascular outside the submitted work. IS is a consultant for Medtronic and Sequent/Microvention outside the published work. IS is a consultant for Sequent/Microvention, Stryker, Medtronic, and Cerenovus outside the submitted work. DH is a consultant for Covidien/Medtronic and Microvention outside the submitted work and has received research support from Siemens. JEDA is a consultant for Medtronic, Penumbra, and Sequent outside the submitted work. LE is a consultant for Codman Neurovascular, Medtronic, MicroVention, Penumbra, Sequent, and Stryker outside the submitted work. SC is a consultant for Medtronic and Sequent/MicroVention outside the submitted work and is a stockholder in ELUM and NDI. JVB provided core laboratory services to Sequent through Oxford University during the conduct of this study and now acts as a consultant for MicroVention and Oxford Endovascular; he is a stockholder of Oxford Endovascular outside the submitted work. DF is a consultant for Balt, Marblehead, Medtronic, Stryker, Microvention, Stryker, Penumbra, and Cerenovus; receives research support from Cerenovus, Medtronic, Stryker, Siemens, Microvention, and Penumbra, and royalties from Codman; and is a stockholder for Marblehead, Neurogami, and Vascular Simulations outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Participating centers with principal investigator (PI) and co-investigator (Co-PI) in order of enrollment (No.): Methodist University Hospital Neuroscience Institute & Cancer Center, Memphis, Tennessee, USA (21), PI: Adam Arthur, MD, Sub-I: Daniel Hoit, MD, Lucas Elijovich, MD; Stony Brook University Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY, United States (12), PI: David Fiorella, MD, Sub-I: Henry Woo, MD; The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, United States (12) PI: Alexander Coon, MD, Sub-I: Geoffrey Colby, MD; Koru Hospital, Ankara, Turkey (11) PI: Isil Saatci, MD, Sub-I: Saruhan Cekirge, MD; National Institute of Neurosciences, Budapest, Hungary (10) PI: Istvàn Szikora, MD; Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Pendik Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey (9) PI: Feyyaz Baltacioğlu, MD, Sub-I: Ruslan Asadov, MD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA (8), PI: Ali Sultan, MD, Sub-I: Ram Chavali, MD, Kai Frerich, MD; Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (7), PI: Josser Delgado, MD, Sub-I: Yasha Kayan, MD; Lyerly Neurosurgery, Baptist Medical Center, Jacksonville, Florida, USA (7), PI: Ricardo Hanel, MD, Sub-I: Eric Sauvageau, MD; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA (7), PI: Raymond Turner, MD, Sub-I: Imran Chaudry, MD, Alejandro Spiotta, MD, Aquila Turk, MD; West Virginia University Medical Center, Morgantown, Virginia, USA (6) PI: Ansaar Rai, MD, Sub-I: Jeffrey Carpenter, MD, Sohyun Boo, MD; Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA (6), PI: Pascal Jabbour, MD, Sub-I Stavropoula Tjoumakaris, MD, Robert Rosenwasser, MD; Fort Sanders Regional Medical Center, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA (5), PI: Keith Woodward, MD; Albany Medical Center, Albany, New York, USA (4) PI: Alan Boulos, MD, Sub-I: John Dalfino, MD, Junichi Yamamoto, MD; Riverside Methodist Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA (4) PI: Nirav Vora, MD, Sub-I: Ronald Budzik, MD, Peter Pema, MD, Thomas Davis, DO; Baptist Memorial Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee, USA (3), PI: Daniel Hoit, MD, Sub-I: Adam Arthur, MD, Lucas Elijovich, MD; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA (3): PI: David Kallmes, MD, Sub-I: Giuseppe Lanzino, MD, Harry Cloft, MD; University at Buffalo Medical Center, Buffalo, New York, USA (2), PI: Adnan Siddiqui, MD, Sub-I: Elad Levy, MD, Kenneth Snyder, MD; Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA (2), PI: Demetrius Lopes, MD, Sub-I: Michael Chen, MD; Mount Sinai Roosevelt Hospital, New York, New York, USA (2) PI: JD Mocco, MD, Sub-I: Johanna Fifi, MD; University of Texas Medical School, Houston, Texas, USA (2) PI: Peng Roc Chen, MD; Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada (2), PI: Michael Kelly, MD, Sub-I: Lissa Peeling, MD; Swedish Medical Center, Englewood, Colorado, USA (1) PI: Don Frei, MD, Sub-I: Daniel Huddle, DO, Richard Bellon, MD, David Loy, MD; Barrow Neurological Institute, St Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona, USA (1) PI: Felipe Albuquerque, MD, Sub-I: Andrew Ducruet, MD; Righospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark (1), PI: Marcus Holtmannspötter, MD; University of Louisville Hospital, Louisville, Kentucky, USA (1), PI: Robert James, MD, Sub-I: Wei Liu, MD; Helios General Hospital, Erfurt, Germany (1) PI: Joachim Klisch, MD, Sub-I: Christoph Strasilla, MD, Christin Clajus, MD. Study proctors in order of cases Proctored (No.): Adam Arthur MD MPH (18), Daniel Hoit MD MPH (15), Saleh Lamin MD (8), Allan Thomas MD (8), David Fiorella MD PhD (8), Josser Delgado MD (7), Tufail Patankar MD (6), Markus Holtmannspotter MD (4), Lucas Elijovich MD (4), Alexander Coon MD (4), Ansgar Berlis MD (1), Imran Chaudry MD (1).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributor Information

WEB-IT Study investigators:

Adam Arthur, Daniel Hoit, Lucas Elijovich, David Fiorella, Henry Woo, Alexander Coon, Geoffrey Colby, Isil Saatci, Saruhan Cekirge, Istvàn Szikora, Feyyaz Baltacioğlu, Ruslan Asadov, Ali Sultan, Ram Chavali, Kai Frerich, Josser Delgado, Yasha Kayan, Ricardo Hanel, Eric Sauvageau, Raymond Turner, Imran Chaudry, Alejandro Spiotta, Aquila Turk, Ansaar Rai, Jeffrey Carpenter, Sohyun Boo, Pascal Jabbour, Stavropoula Tjoumakaris, Robert Rosenwasser, Keith Woodward, Alan Boulos, John Dalfino, Nirav Vora, Ronald Budzik, Peter Pema, Thomas Davis, David Kallmes, Giuseppe Lanzino, Harry Cloft, Adnan Siddiqui, Elad Levy, Kenneth Snyder, Demetrius Lopes, Michael Chen, JD Mocco, Johanna Fifi, Peng Roc Chen, Michael Kelly, Lissa Peeling, Don Frei, Daniel Huddle, Richard Bellon, David Loy, Felipe Albuquerque, Andrew Ducruet, Marcus Holtmannspötter, Robert James, Wei Liu, Joachim Klisch, Christoph Strasilla, Christin Clajus, Saleh Lamin, Allan Thomas, Tufail Patankar, Markus Holtmannspotter, and Ansgar Berlis

Collaborators: WEB-IT Study investigators

References

- 1. Fiorella D, Arthur AS, Chiacchierini R, et al. How safe and effective are existing treatments for wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms? Literature-based objective performance criteria for safety and effectiveness. J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:1197–201. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clajus C, Strasilla C, Fiebig T, et al. Initial and mid-term results from 108 consecutive patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with the WEB device. J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:411–7. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klisch J, Sychra V, Strasilla C, et al. The Woven EndoBridge cerebral aneurysm embolization device (WEB II): initial clinical experience. Neuroradiology 2011;53:599–607. 10.1007/s00234-011-0891-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behme D, Berlis A, Weber W. Woven endobridge intrasaccular flow disrupter for the treatment of ruptured and unruptured wide-neck cerebral aneurysms: Report of 55 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:1501–6. 10.3174/ajnr.A4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pierot L, Costalat V, Moret J, et al. Safety and efficacy of aneurysm treatment with WEB: results of the WEBCAST study. J Neurosurg 2016;124:1250–6. 10.3171/2015.2.JNS142634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pierot L, Klisch J, Liebig T, et al. WEB-DL endovascular treatment of wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms: long-term results in a European series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:2314–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A4445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pierot L, Moret J, Barreau X, et al. Safety and efficacy of aneurysm treatment with WEB in the cumulative population of three prospective, multicenter series. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:553–9. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pierot L, Moret J, Turjman F, et al. WEB Treatment of intracranial aneurysms: clinical and anatomic results in the French Observatory. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:655–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pierot L, Spelle L, Molyneux A, et al. Clinical and anatomical follow-up in patients with aneurysms treated with the web device: 1-year follow-up report in the cumulated population of 2 prospective, multicenter series (WEBCAST and French Observatory). Neurosurgery 2016;78:133–41. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arthur A, Hoit D, Coon A, et al. Physician training protocol within the WEB Intrasaccular Therapy (WEB-IT) study. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:500–4. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spelle L, Liebig T. Letter to the editor. Neuroradiol J 2014;27:369 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiorella D, Molyneux A, Coon A, et al. Demographic, procedural and 30-day safety results from the WEB Intra-saccular Therapy Study (WEB-IT). J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:1191–6. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fiorella D, Arthur A, Byrne J, et al. Interobserver variability in the assessment of aneurysm occlusion with the WEB aneurysm embolization system. J Neurointerv Surg 2015;7:591–5. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rouchaud A, Brinjikji W, Ding YH, et al. Evaluation of the angiographic grading scale in aneurysms treated with the WEB device in 80 rabbits: correlation with histologic evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:324–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A4527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bechan RS, Sprengers ME, Majoie CB, et al. Stent-assisted coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms: complications in acutely ruptured versus unruptured aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:502–7. 10.3174/ajnr.A4542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiorella D, Albuquerque FC, Woo H, et al. Neuroform in-stent stenosis: Incidence, natural history and treatment strategies. Neurosurgery 2006;59:34–42. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000219853.56553.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiorella D, Albuquerque FC, Woo H, et al. Neuroform stent assisted aneurysm treatment: evolving treatment strategies, complications and results of long term follow-up. J Neurointerv Surg 2010;2:16–22. 10.1136/jnis.2009.000521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hetts SW, Turk A, English JD, et al. Stent-assisted coiling versus coiling alone in unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the matrix and platinum science trial: safety, efficacy, and mid-term outcomes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:698–705. 10.3174/ajnr.A3755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hwang G, Kim JG, Song KS, et al. Delayed ischemic stroke after stent-assisted coil placement in cerebral aneurysm: characteristics and optimal duration of preventative dual antiplatelet therapy. Radiology 2014;273:194–201. 10.1148/radiol.14140070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Leacy RA, Fargen KM, Mascitelli JR, et al. Wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery and basilar apex treated by endovascular techniques: a multicentre, core lab adjudicated study evaluating safety and durability of occlusion (BRANCH). J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:31–6. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fiorella D, Boulos A, Turk AS, et al. The safety and effectiveness of the LVIS stent system for the treatment of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms: final results of the pivotal US LVIS trial. J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:357–61. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becske T, Kallmes DF, Saatci I, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology 2013;267:858–68. 10.1148/radiol.13120099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W, Boccardi E, et al. Aneurysm Study of Pipeline in an Observational Registry (ASPIRe). Interv Neurol 2016;5(1-2):89–99. 10.1159/000446503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kallmes DF, Hanel R, Lopes D, et al. International retrospective study of the pipeline embolization device: a multicenter aneurysm treatment study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:108–15. 10.3174/ajnr.A4111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nelson PK, Lylyk P, Szikora I, et al. The pipeline embolization device for the intracranial treatment of aneurysms trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:34–40. 10.3174/ajnr.A2421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;11:304–14. 10.1053/jscd.2002.130390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, et al. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Lancet 2015;385:691–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60975-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Birks J, et al. Risk of recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage, death, or dependence and standardised mortality ratios after clipping or coiling of an intracranial aneurysm in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT): long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:427–33. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70080-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Albuquerque FC, et al. The Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial: 3-year results. J Neurosurg 2013;119:146–57. 10.3171/2013.3.JNS12683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Zabramski JM, et al. The Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial: 6-year results. J Neurosurg 2015;123:609–17. 10.3171/2014.9.JNS141749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Geyik S, Yavuz K, Yurttutan N, et al. Stent-assisted coiling in endovascular treatment of 500 consecutive cerebral aneurysms with long-term follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:2157–62. 10.3174/ajnr.A3574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lecler A, Raymond J, Rodriguez-Régent C, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: recurrences more than 10 years after endovascular treatment-a prospective cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Radiology 2015;277:173–80. 10.1148/radiol.2015142496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turk AS, Johnston SC, Hetts S, et al. Geographic differences in endovascular treatment and retreatment of cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:2055–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A4857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]