Abstract

Particulate matter (PM), which refers to the mixture of particles present in the air, can have harmful effects. Damage to cells by PM, including disruption of organelles and proteins, can trigger autophagy, and the relationship between autophagy and PM has been well studied. However, the cellular regulators of PM-induced autophagy have not been well characterized, especially in keratinocytes. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) is expressed in the epidermis and is activated by PM. In this study, we investigated the role of the AhR in PM-induced autophagy in HaCaT cells. Our results showed that PM led to AhR activation in keratinocytes. Activation of the AhR-target gene CYP1A1 by PM was reduced by co-treatment with α-naphthoflavone (α-NF), an AhR inhibitor. We also evaluated activation of the autophagy pathway in PM-treated keratinocytes. In HaCaT cells, treatment with PM treatment led to the induction of microtubules-associated proteins light chain 3 (LC3) and p62/SQSTM1, which are essential components of the autophagy pathway. To study the role of the AhR in mediating PM-induced autophagy, we treated cells with α-NF or used an siRNA against AhR. Expression of LC3-ІІ induced by PM was decreased in a dose dependent manner by α-NF. Furthermore, knockdown of AhR with siAhR diminished PM-induced expression of LC3-ІІ and p62. Together, these results suggest that inhibition of the AhR decreases PM-induced autophagy. We confirmed these results using the autophagy-inhibitors BAF and 3-MA. Taken together, our results indicate that exposure to PM induces autophagy via the AhR in HaCaT keratinocytes.

Keywords: PM, AhR, Autophagy, LC3, p62, Keratinocytes

INTRODUCTION

Particulate matter (PM) refers to mixtures of particles in the air. The major sources of PM include factories, automobiles, construction activities, and natural windblown dust (Dagouassat et al., 2012). PM generally consists of ions, organic compounds, metals, and particle carbon cores (Folinsbee, 1993; Li et al., 2017). PM can be divided into three types according to size, and different sizes of PM are associated with different effects and patterns of damage. Specifically, PM0.1 (Ultrafine particles<0.1 μm) are able to pass into the circulatory system, PM2.5 (Fine particles, <2.5 μm) are able to penetrate and deposit in alveoli and lungs, and PM10 (Inhalable particles <10 μm) deposit in the bronchi and bronchioles. Although the effects of PM have been studied in various organs, the mechanism of the detrimental effects of PM in keratinocytes remains unclear.

The Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix PER/ARNT/SIM family of transcription factors, and is regarded as an essential regulator of cell physiology and homeostasis. In addition, roles of the AhR in immune system regulation, cardiovascular regulation, hepatic cancer, and lung cancer have all been described (degrMulero-Navarro and Fernandez-Salguero, 2016). The AhR is activated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAH), including the well-known exogenous ligand 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (Ma and Baldwin, 2000). Additionally, FICZ, a UV-B photo-product, is also regarded as an agonist of the AhR (Wincent et al., 2012). The AhR is bound to molecular complexes (Hsp90, XAP2 and p23) and resides in the cytoplasm. When PAHs or PM acting as AhR ligands reach cells of the epidermis, they cause the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator/Hypoxia-inducible factor1b (ARNT/HIF1b) to heterodimerize with AhR and translocate to the nucleus (Swanson et al., 1995). AhR/ARNT then bind to consensus xenobiotic responsive elements (XRE, 5′-GCGTG-3′) located upstream of target genes (e.g., cytochromes P450 such as CYP1A1) (Hankinson, 1995). During transcription, the AhR-ARNT complex is disrupted, and the AhR is displaced to the cytosol where it undergoes proteasomal degradation (Davarinos and Pollenz, 1999). Many studies have been published on the effects of AhR in melanogenesis (Abbas et al., 2017), cell differentiation (van den Bogaard et al., 2015), and in mediating the harmful effects of environmental contaminants such as benzo(a)pyrene (Bap) (Tsuji et al., 2011). However, the molecular mechanisms of PM-mediated AhR activation in keratinocytes have not been well characterized.

Autophagy is activated during the accumulation of damaged organelles and proteins. During the process of autophagy, cells begin to undergo self-digestion in order to form nutrients and retain intracellular homeostasis. Autophagy is an essential process for maintaining tissue homeostasis under normal conditions, but it is also associated with cancer progression. There are three major forms of autophagy, namely, chaperone mediated autophagy, microautophagy, and macroautophagy. Macroautophagy, which is the form that researchers generally refer to when describing autophagy, is induced in response to cellular stress and starvation (He and Klionsky, 2009). Specific autophagy related genes (ATGs) including microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3 (LC3) and p62/SQSTM1 are expressed during autophagy, and these proteins are involved in the formation of the autophagosome. In mammalian cells, there are two forms of LC3, namely, LC3-І and LC3-ІІ. LC3-І is the unprocessed form of LC3, while LC3-ІІ represents the converted form of LC3-І generated after activated LC3-І is conjugated to highly lipophilic phosphatidylethanolamine by ATGs. In turn, phosphatidylethanolamine conjugation promotes incorporation of LC3-ІІ into the autophagosome (Netea-Maier et al., 2016). p62/SQSTM1, which is an autophagic effector protein, interacts with LC3 by serving as a cargo protein that facilitates autophagy-mediated protein degradation (Bjorkoy et al., 2005). Thus, expression of LC3-ІІ and p62 are regarded as markers of autophagosome formation.

Autophagy can be studied using the specific inhibitors 3-Methyladenine and Bafilomycin A1. 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) is used commonly as an inhibitor of autophagy, and it acts by inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)1 by blocking autophagosome formation. In this way, inhibition of PI3K with 3-MA inhibit autophagy sequestration. On the other hand, BAF blocks fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes by inhibiting vacuolar H+ ATPase. Inhibition of autophagosomes and lysosomes is thus a useful method for evaluating induction of autophagy (Mizushima, 2004).

Autophagy exerts diverse effects according to cell type. In vascular endothelial cells, autophagy-induced by PM2.5 decreases cell cytotoxicity (Zhou et al., 2018). In addition, compounds such as resveratrol protect lung cells from PM-induced oxidative injury by inducing autophagy (Li et al., 2018). However, to date, there have been no studies on the relationship between PM-induced autophagy and AhR activation. Here, we attempted to elucidate the role of the AhR in mediating PM-induced autophagy in keratinocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental material

Fine Dust (PM10–like) was purchased from ERM(European Reference Materials). Fine Dust particles are consisted of the size range of 10 μm (x ≤10 μm). LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (CA, USA). α-Naphthoflavone (α-NF), 3-Methyladenine (3-MA), and Bafilomycin A1 (BAF) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cells were incubated at a density of 1×104 cells/well in 96-well plates. After 24 h at 37°C, the media was replaced with PM diluted to the appropriate concentrations for 24 h. Next, the cells were washed with DPBS and EZ-Cytox reagent (Daeil Lab Service, Seoul, Korea) was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 40 min. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Cell culture

HaCaT are an immortalized keratinocyte cell line. HaCaT keratinocytes were cultured in DMEM (Welgene, Gyeongsan, Korea) medium supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

SiRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Bioneer. The sense and antisense sequences for individual duplexes targeting human AhR were as follows:

AhR sense 5′-UCAUGCAGCUGAUAUGCUU(dTdT)-3′, antisense 5′-AAGCAUAUCAGCUGCAUGA(dTdT)-3′.

siRNAs Transfection

Cells were seeded in six-well plates in DMEM. One day later, when the cells reached 40–50% confluence, they were treated with 50 nM siRNA mixed with LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) for 6 h followed by incubation in DMEM with 2% FBS for 3 h.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a Fast-Start Essential DNA Probe Master kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with a Universal Probe Library (Roche). The probes for CYP1A1 (#2, NM_000499) were designed using the Probe Library Assay Design Center. Gene expression levels were normalized to human β-actin. Synthesized cDNA was amplified with the following primers: CYP1A1 sense 5′-GGT CAAGGAGCACTACAAAACC-3′; antisense 5′-TGGACATTG GCGTTCTCAT-3′.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

For RT-PCR, 1ul each of cDNA and respective primers were added to HiPi PCR preMix (ELPIS BIO, Daejeon, Korea). The synthesized cDNA was amplified with the following primers:

β–actin sense 5′-GGCATCGTGATGGACTCCG-3′; antisense 5′-GCTGGAA-GGTGGACAGCGA-3′; CYP1A1 sense 5′-TCTTTCTCTTCCTGGCTATC-3′; antisense 5′-CTGTCTCTT-CCCTTCACTCT-3′; AhR sense 5′-TACTGAAG CAGAGCTGT GCA-3′; antisense 5′-CTCATACAACACAGCTTCTCC-3′; p62 sense 5′-CTGCCCAGACTACGACT-TGTGT-3′; antisense 5′-TCAACTTCAATGCCCAGAGG-3′. The finished PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis separation on 2% agarose gels with staining RedSafeTM Nucleic Acid Staining Solution (Intron Bio, Seongnam, Korea).

Western blot

Cells were seeded in six-well plates in DMEM. One day later, after washing in DPBS, the cells were treated with diluted sample in DMEM with FBS 2% for pre-determined amounts of time. Following treatment, the cells were washed in DPBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (Noble Bio, Hwaseong, Korea) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC, Sigma Aldrich) and 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min at 4°C. The lysate were subjected to centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and the resulting supernatant was stored on ice for immediate use or –20°C for longer term storage. The protein content of the supernatant was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Equal amounts of protein were separated by NuPAGETM 12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen) or BoltTM 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus (Invitrogen) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Antibodies against β–actin (1:20000, Sigma Aldrich), AhR (1:500, Thermo Scientific), CYP1A1 (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), LC3 (1:750, Novus Biologicals, St. Colorado, Littleton), and p62/SQSTM1 (1:1000, Abcam) were used at 4°C for 24 h. Blots were then incubated with Horse-radish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse (1:20000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) or anti-rabbit (1:5000, Bethyl, Montgomery, TX, USA) secondary antibodies as appropriate at 4°C for 2 h. Blots were visualized by adding a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, USA) and imaged with a FlourChem E imager (HNS Bio, Seoul, Korea).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by independent t-test. A value of *p<0.05, **p<0.01, or ***p<0.001 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Particulate matter treatment activates the AhR in keratinocytes

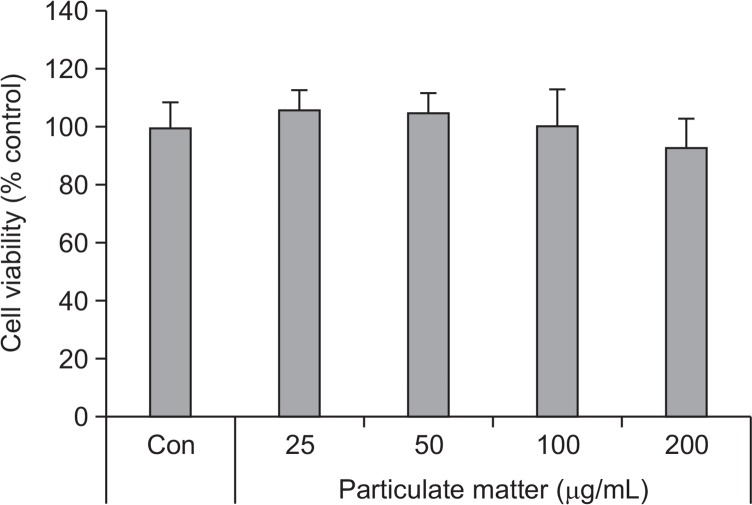

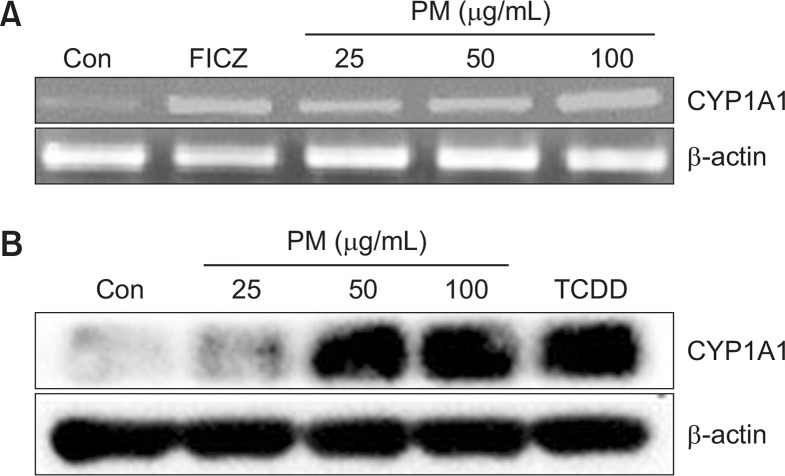

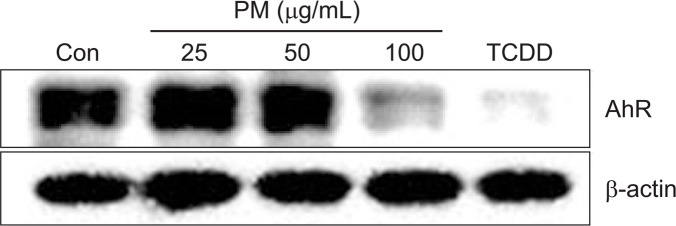

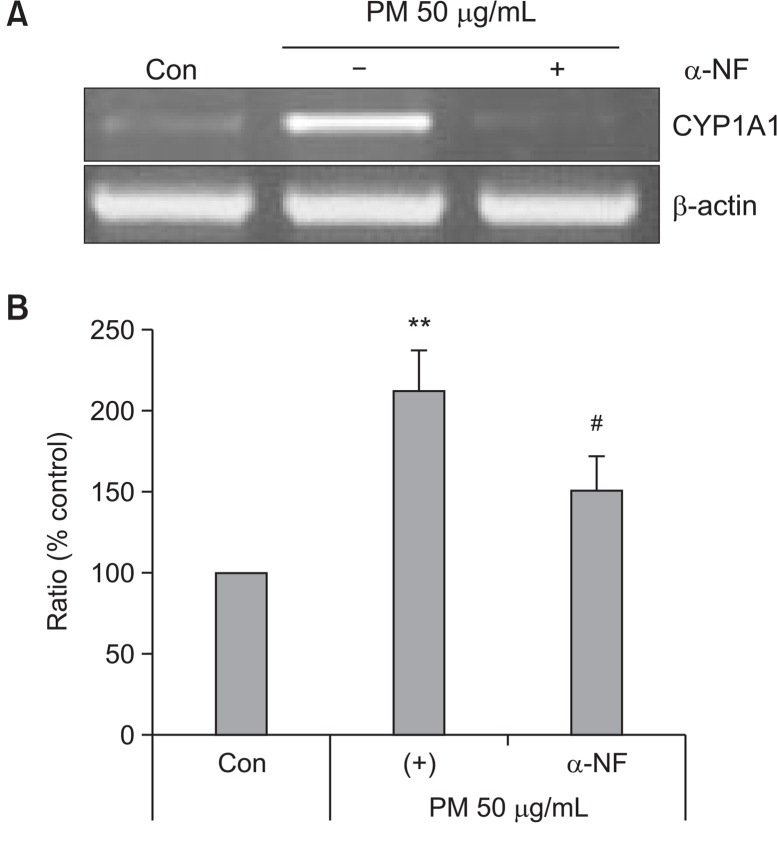

To determine the cytotoxic effects of PM, HaCaT cells were treated with different concentrations of PM (25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL). No cytotoxicity with PM was observed up to concentrations between 25 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL (Fig. 1). To determine whether PM treatment led to activation of the AhR, we investigated expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP1A1), a biomarker of AhR activation (Swanson, 2004). mRNA levels of CYP1A1 were increased by treatment with both PM and FICZ in a dose-dependent manner (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) (Fig. 2A). Protein expression of CYP1A1 was also increased by PM and TCDD in a dose-dependent manner (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) (Fig. 2B). Additionally, AhR was degraded by PM treatment in a dose-dependent manner (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) (Fig. 3). To verify whether CYP1A1 induction was specific to the AhR, we co-treated cells with α-NF, an AhR inhibitor (Forrester et al., 2014). The level of CYP1A1 mRNA induced by PM (50 μg/mL) was decreased upon co-treatment with α-NF (Fig. 4A, 4B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of PM on keratinocyte viability. Cell viability was assessed using the Ez-Cytox assay and measured at 450 nm. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n=3).

Fig. 2.

Particulate matter (PM) increases the expression of CY-P1A1 in keratinocytes. (A) Cells were treated with different concentration of PM (25, 50, 100 μg/mL) and FICZ (5 nM) for 3 h before harvest and were analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) Cells were treated with different concentrations of PM (25, 50, 100 μg/mL), and TCDD (10 nM) for 24 h and analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as the loading control.

Fig. 3.

Particulate matter treatment leads to degradation of Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in keratinocytes. Cells were treated with different concentrations (AhR) of PM (25, 50, 100 μg/mL) for 24 h and TCDD (10 nM) for 3 h and analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 4.

α-NF stimulation decreases the expression of CYP1A1 in keratinocytes. Cells were treated with PM 50 μg/mL in the absence or presence of α-NF (6 h; 5 μM) for 3 h and analyzed by (A) RT-PCR and (B) qRT-PCR. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n=3). **p<0.01 compared with control, #p<0.05 compared with PM50 μg/mL.

Particulate matter treatment induces autophagy in keratinocytes

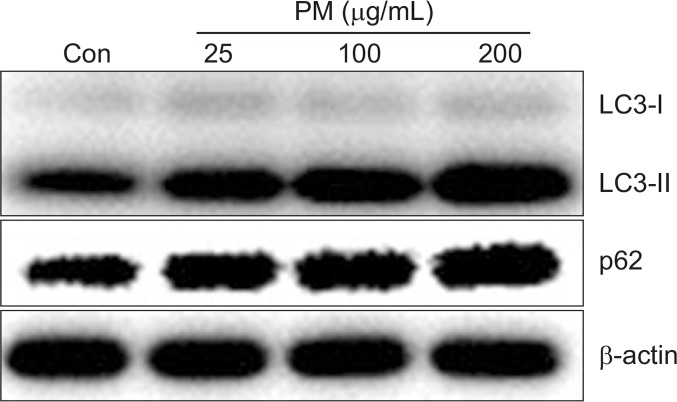

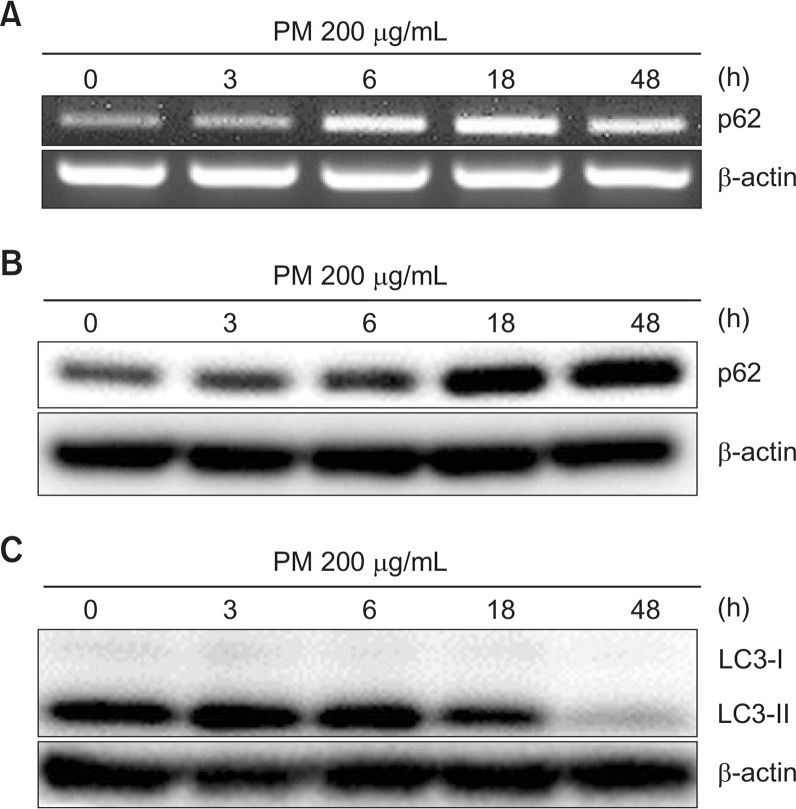

Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) and p62/SQSTM1 are essential proteins in autophagy. To determine whether autophagy is induced by PM in HaCaT keratinocytes, we checked the expression of LC3 and p62 protein after treatment with PM (25, 100, and 200 μg/mL). Treatment with PM increased LC3-II and p62 in a dose dependent manner, suggesting that PM induced autophagy in HaCaT cells (Fig. 5). To evaluate the time course of PM-induced autophagy, we measured the expression of p62 and LC3-II at 0, 3, 6, 18, and 48 h after PM treatment. mRNA levels of p62 were significantly increased after PM treatment for 6 h, with maximum expression observed after 18 h that was sustained through 48 h. And protein levels of p62 started to increase after treatment for 6 h. Likewise, LC3-II expression was elevated at 3 h and sustained through 18 h and decreased to 48 h (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Particulate matter treatment induces the expression of LC3 in keratinocytes. Cells were treated with different concentrations of PM10 (25, 100, 200 μg/mL) for 24 h and analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 6.

Particulate matter treatment induces autophagy in keratinocytes. (A) Cells were treated with PM 200 μg/mL for the indicated periods of time and were analyzed by RT-PCR or (B, C) Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

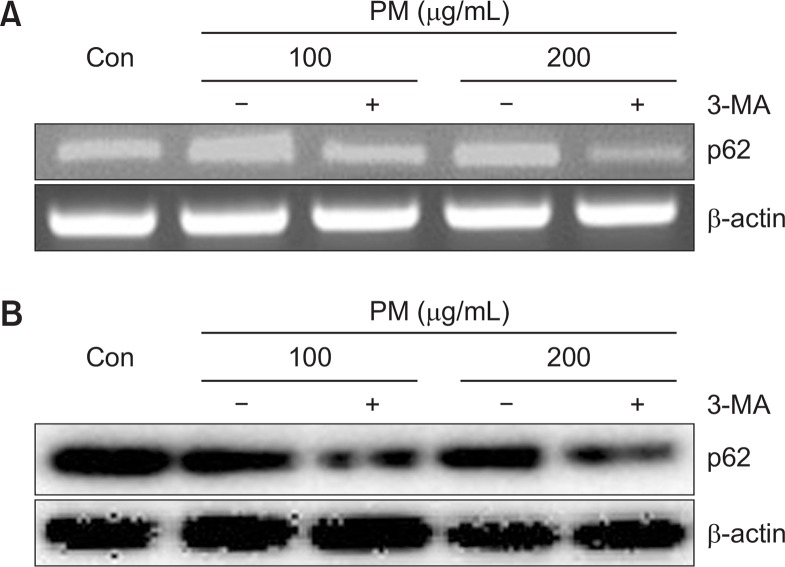

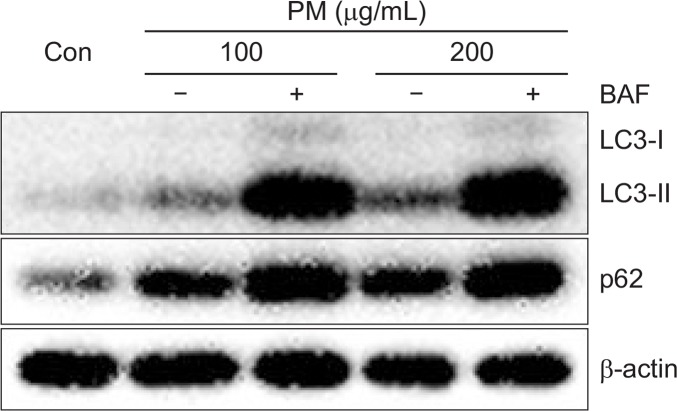

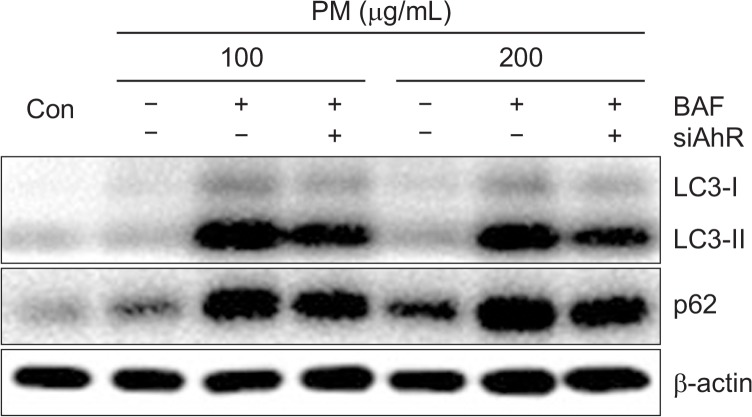

We next evaluated PM-induced autophagy activation by tracking LC3-I and LC3-II. Activation of autophagy by PM was evaluated using specific inhibitors of autophagosomelysosome fusion, namely, Bafilomycin A1 (BAF) and 3-Methyladenine (3-MA). mRNA levels of p62 were decreased in the presence of 3-MA (Fig. 7A). Likewise, protein expression of p62 was also decreased in the presence of 3-MA compared to treatment with PM alone (Fig. 7B). Both LC3-II and p62 accumulated upon treatment with BAF, an inhibitor of lysosomal degradation in PM-treated keratinocytes. Accumulation of LC3-II and p62 was significantly increased by high concentrations of PM in the presence of BAF compared to lower concentration of PM with BAF (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Treatment with 3-MA decreases mRNA and protein levels of p62 in keratinocytes. Cells were co-treated with different concentrations of PM (100, 200 μg/mL) and 3-MA (10 mM) for 6 h or 18 h and were analyzed by (A) RT-PCR or (B) Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 8.

Treatment with BAF leads to accumulation of LC3 and expression of p62 in keratinocytes. Cells were treated with different concentrations of PM (100, 200 μg/mL) for 18 h in the absence or presence of BAF (2 h; 100 nM) and were analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

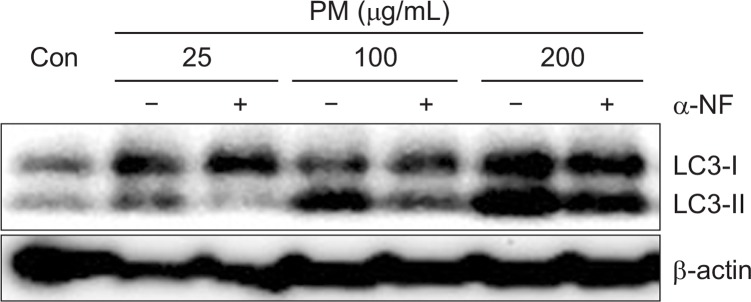

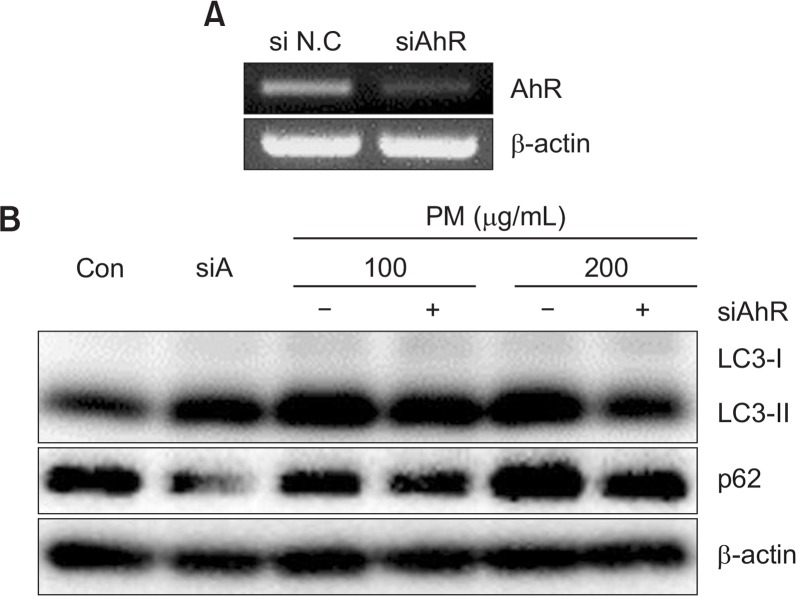

Particulate matter activates autophagy in keratinocytes through the AhR

To determine whether AhR is required for activation of autophagy by PM, we measured the expression of LC3-II with PM and α-NF. LC3-II expression induced by PM was significantly decreased by α-NF, suggesting that the AhR is required for induction of autophagy (Fig. 9). In order to evaluate the role of AhR in autophagy induction, we used an AhR knockdown approach. Knockdown of the AhR by siRNA transfection resulted in noted attenuation of LC3-II and p62 induced by PM in keratinocytes (Fig. 10A, 10B). The effect of siAhR was more prominent with higher PM concentrations (200 μg/mL) compared to lower PM concentrations (100 μg/mL). These results suggest that the AhR is an integral component of PM-induced autophagy induction. In order to confirm whether activation of autophagy requires the AhR, we co-treated PM-exposed keratinocytes with BAF and siAhR. We found that the increased levels of LC3-II induced by PM were more significantly decreased by co-treatment with BAF and siAhR compared with BAF alone. Lastly, levels of p62 were also slightly decreased in the presence of BAF and siAhR (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9.

α-NF stimulation decreases the LC3 in keratinocytes. Cells were treated with different concentrations of PM (25, 100, 200 μg/mL) and α-NF (6 h; 5 μM) for 24 h and analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 10.

Knockdown of AhR decreases the abundance of LC3 and expression of p62 in keratinocytes. (A) Cells were transfected with siNC or siRNAs specific for AhR (siAhR) and were analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) Cells were transfected with siNC or siRNAs specific for AhR (siAhR) followed by different concentrations of PM (100, 200 μg/mL) for 18 h and were analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 11.

The combination of AhR knockdown and BAF treatment decreases levels of LC3 and expression of p62 in keratinocytes. Cells were transfected with siNC or siRNAs specific for AhR (siAhR) followed by treatment with different concentrations of PM (100, 200 μg/mL) for 18 h in the presence or absence of BAF (2 h; 100 nM). Cells were analyzed by Western blot, and β-actin was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated a relationship between PM exposure and autophagy in several cells types, including A549 lung cancer cells and macrophages. Specifically, lung cancer cell migration is inhibited by AhR-regulated autophagy (Tsai et al., 2017), and autophagy in macrophages is induced by particulate matter via oxidative stress (Su et al., 2017). However, the relationship between PM and autophagy in the skin remains unclear.

In the present study, we found that mRNA and protein level of CYP1A1 in HaCaT cells were increased upon treatment with PM (Fig. 2). It is well known that the AhR undergoes degradation upon translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm following activation (Ma and Baldwin, 2000). Consistent with PM-mediated AhR activation, we found that protein levels of the AhR were degraded in HaCaT cells upon treatment with PM (Fig. 3). Additionally, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) dimerized in nucleus is associated with AhR localization. Thus, expression of nuclear extract, cytosolic extracts and ARNT also be markers of AhR activation by PM (van den Bogaard et al., 2015). Several previous reports have shown that flavonoids are able to inhibit damage to cells caused by air pollution because flavonoids have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Izawa et al., 2008). Cotreatment of HaCaT cells with PM and α-naphthoflavone (α-NF), a flavonoid and AhR inhibitor, led to decreased CYP1A1 expression (Fig. 4).

Autophagy is regulated by autophagy related genes (ATGs) and begins with formation of the phagophore. Several proteins including LC3-II and p62 are induced during autophagy as well (Das et al., 2016). We confirmed that PM induces autophagy in keratinocytes, and found that both LC3 and p62 were induced by treatment with PM (Fig. 5, 6). The role of p62 accumulation in carcinogenesis and bronchial disease remains controversial, and it has been reported that accumulation of p62 can indicate apoptosis or pro-survival mechanisms (Guo et al., 2013). In the present study, in order to confirm the specific-induction of autophagy by PM, we used inhibitors of early (3-MA) and late (BAF) autophagy. Our results showed that p62 accumulation induced by PM was decreased by 3-MA (Fig. 7) while LC3 and p62 levels were increased by BAF (Fig. 8). As previous studies suggest that autophagy can cause either deleterious or cytoprotective depending on different stimulation (Das et al., 2016), additional studies on the consequences of p62 accumulation are needed.

Taken together, our study showed that PM induces toxic effects and autophagy in HaCaT cells. Similarly, tobacco generated by cigarette smoking causes LC3-II accumulation, suggesting that tobacco may act as an autophagic flux inducer through ROS generation, which may explain some of the toxic effects of autophagy (Sannigrahi et al., 2015). To study the relationship between AhR activation by PM and autophagy, we utilized the AhR inhibitor α-naphthoflavone (α-NF). Compared to PM alone, treatment with PM and α-NF led to decreased levels of LC3-II in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 9). Additionally, knockdown of AhR reduced LC3 levels and p62 accumulation by PM (Fig. 10). Accumulated LC3-II and p62 level were also lower in BAF and siAhR treated cells compared to cells treated with BAF alone (Fig. 11). This result suggested that knockdown of AhR contributes to the reduction of LC3 and p62 accumulated by BAF and autophagy induction. In summary, our results suggest that the AhR mediates PM-induced autophagy in HaCaT keratinocytes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Gyeonggi Technology Development Program funded by Gyeonggi Province, Republic of Korea (Grant NO: D171754).

REFERENCES

- Abbas S, Alam S, Singh KP, Kumar M, Gupta SK, Ansari KM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation contributes to benzanthrone-induced hyperpigmentation via modulation of melanogenic signaling pathways. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30:625–634. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagouassat M, Lanone S, Boczkowski J. Interaction of matrix metalloproteinases with pulmonary pollutants. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1021–1032. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00195811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das DN, Naik PP, Nayak A, Panda PK, Mukhopadhyay S, Sinha N, Bhutia SK. Bacopamonnieri-induced protective autophagy inhibits benzo[a]pyrene-mediated apoptosis. Phytother Res. 2016;30:1794–1801. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davarinos NA, Pollenz RS. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor imported into the nucleus following ligand binding is rapidly degraded via the cytosplasmic proteasome following nuclear export. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28708–28715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folinsbee LJ. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;100:45–56. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9310045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester AR, Elias MS, Woodward EL, Graham M, Williams FM, Reynolds NJ. Induction of a chloracne phenotype in an epidermal equivalent model by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is dependent on aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation and is not reproduced by aryl hydrocarbon receptor knock down. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;73:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Dong Y, Yin S, Zhao C, Huo Y, Fan L, Hu H. Patulin induces pro-survival functions via autophagy inhibition and p62 accumulation. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e822. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu Rev Phamacol Toxicol. 1995;35:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa H, Kohara M, Aizawa K, Suganuma H, Inakuma T, Watanabe G, Taya K, Sagai M. Alleviative effects of quercetin and onion on male reproductive toxicity induced by diesel exhaust particles. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:1235–1241. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Kang Z, Jiang S, Zhao J, Yan S, Xu F, Xu J. Effects of ambient fine particles PM2.5 on human HaCaT cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:E72. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Fu S, Li E, Sun X, Xu H, Meng Y, Wang X, Chen Y, Xie C, Geng S, Wu J, Zhong C, Xu P. Modulation of autophagy in the protective effect of resveratrol on PM2.5-induced pulmonary oxidative injury in mice. Phytother Res. 2018;32:2480–2486. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Baldwin KT. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced degradation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Role of the transcription activation and DNA binding of AhR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8432–8438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2491–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulero-Navarro S, Fernandez-Salguero PM. New trends in aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016;4:45. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea-Maier RT, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, Smit JW, Netea MG. Modulation of inflammation by autophagy: consequences for human disease. Autophagy. 2016;12:245–260. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1071759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sannigrahi MK, Singh V, Sharma R, Panda NK, Khullar M. Role of autophagy in head and neck cancer and therapeutic resistance. Oral Dis. 2015;21:283–291. doi: 10.1111/odi.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HI, Chan WK, Bradfield CA. DNA binding specificities and pairing rules of the Ah receptor, ARNT, and SIM proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26292–26302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HI. Cytochrome P450 expression in human keratinocytes: an aryl hydrocarbon receptor perspective. Chem Biol Interact. 2004;149:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su R, Jin X, Zhang W, Li Z, Liu X, Ren J. Particulate matter exposure induces the autophagy of macrophages via oxidative stress-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Chemosphere. 2017;167:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CH, Li CH, Cheng YW, Lee CC, Liao PL, Lin CH, Huang SH, Kang JJ. The inhibition of lung cancer cell migration by AhR-regulated autophagy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41927. doi: 10.1038/srep41927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji G, Takahara M, Uchi H, Takeuchi S, Mitoma C, Moroi Y, Furue M. An environmental contaminant, benzo(a)pyrene, induces oxidative stress-mediated interleukin-8 production in human keratinocytes via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;62:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaard EH, Podolsky MA, Smits JP, Cui X, John C, Gowda K, Desai D, Amin SG, Schalkwijk J, Perdew GH, Glick AB. Genetic and pharmacological analysis identifies a physiological role for the AHR in epidermal differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1320–1328. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincent E, Bengtsson J, MohammadiBardbori A, Alsberg T, Luecke S, Rannug U, Rannug A. Inhibition of cytochrome P4501-dependent clearance of the endogenous agonist FICZ as a mechanism for activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4479–4484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118467109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Shao T, Qin M, Miao X, Chang Y, Sheng W, Wu F, Yu Y. The effects of autophagy on vascular endothelial cells induced by airborne PM2.5. J Environ Sci (China) 2018;66:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]