Abstract

The ABCG5/G8 heterodimer is the primary neutral sterol transporter in hepatobiliary and transintestinal cholesterol excretion. Inactivating mutations on either the ABCG5 or ABCG8 subunit cause Sitosterolemia, a rare genetic disorder. In 2016, a crystal structure of human ABCG5/G8 in an apo state showed the first structural information on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) sterol transporters and revealed several structural features that were observed for the first time. Over the past decade, several missense variants of ABCG5/G8 have been associated with non-Sitosterolemia lipid phenotypes. In this review, we summarize recent pathophysiological and structural findings of ABCG5/G8, interpret the structure-function relationship in disease-causing variants and describe the available evidence that allows us to build a mechanistic view of ABCG5/G8-mediated sterol transport.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporters, cardiovascular disease, cholesterol transport, lipid metabolism, sitosterolemia, structural biology

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally (∼50% deaths of non-communicable diseases) with an estimated total global cost of $1 trillion (US Dollar) by 2030 [1]. Abnormal elevations in plasma cholesterol contributes to hyperlipidemia, a critical factor leading to cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic disorders [2]. Conversely, lipids are the primary component of cellular membranes, forming the natural barriers for intracellular compartments and the checkpoints during the transmission of molecules and signals from the extracellular milieu. As a key component of mammalian cellular membranes, cholesterol accounts for ∼40% of the total lipid content in the plasma membrane [3] and serves as the precursor molecule for steroid hormones that modulate gene regulation and for bile acids that are required for nutrient absorption. Cholesterol is the exclusive sterol synthesized from acetyl-CoA and utilized by mammalian species, although other sterols are an integral part of their diet. Non-cholesterol sterols (xenosterols) from plants, fish and other dietary sources exhibit poor bioavailability, with <5% absorption and efficient biliary elimination [4]. Since few cells have the capacity to metabolize cholesterol, elimination through biliary and intestinal secretion is essential to maintain homeostasis. Whether derived from the diet or de novo synthesis, sterols in peripheral tissues are mobilized to high density lipoproteins (HDL) and ultimately delivered to the liver or intestine for elimination in the reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) pathway [5,6]. While elimination of excess cholesterol is vital for life, little is known about the mechanisms underlying the control of sterol shuttling across lipid-bilayer membranes.

Lipid-transport membrane proteins have been shown to be essential for the translocation of sterols and phospholipids to maintain lipid homeostasis, cellular functions, and the structural integrity of mosaic lipid bilayers [7–9]. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are major sterol exporters responsible for both cholesterol efflux from peripheral cells and the elimination of excess cholesterol and dietary sterols [10,11]. ABC transporters comprise one of the largest evolutionarily conserved membrane protein families, which can transport a variety of substrates across the plasma membrane [12]. The minimal functional unit of an ABC transporter includes two transmembrane domains (TMDs) and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), where the transport function is generally believed to be driven by the ‘power stroke’ upon the NBD dimerization, in which ATP is bound and hydrolyzed. Given such diversity in transport substrates, it is no surprise that the TMDs have been found to be structurally diverse, suggesting distinctive transport mechanisms for individual transporters [13]. Human subfamily-G transporters are mostly associated with lipid and sterol metabolism, including ABCG1/4/5/8. ABCG1 and ABCG4 mediate cholesterol trafficking in the plasma membrane and endosomes [14,15] and are believed to regulate cholesterol homeostasis in the brain and the macrophage-rich tissues [16]. ABCG5 and ABCG8 function as a heterodimeric complex (ABCG5/G8) and are responsible for biliary and transintestinal secretion of cholesterol and dietary sterols. Inactivating mutations in ABCG5/G8 cause Sitosterolemia, a rare autosomal recessive disease [17–19], and several missense mutations on either gene have been associated with lipid phenotypes, such as the appearance of gallstones or the elevation of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels [20–31]. In vivo, the loss-of-function phenotype of ABCG5/G8 has been recapitulated by mouse models [32,33]. Our recent determination of a crystal structure of human ABCG5/G8 (PDB accession number: 5DO7) represents the first high-resolution model of sterol/cholesterol transporters and provides a structural basis to further examine the function of ABCG5/G8 and its mechanisms on sterol translocation in cell membranes [34]. In light of this structural data and various lipid phenotypes of ABCG5/G8 variants, the objectives of this review are to summarize our mechanistic interpretation based on the ABCG5/G8 structure and to provide a structural basis of pathophysiological variants in the hepatobiliary cholesterol secretion.

ABCG5/G8, Sitosterolemia and cholesterol homeostasis

In normal diets, the levels of cholesterol and non-cholesterol sterols are usually equal. However, 50–60% of dietary cholesterol is absorbed, while <5% of the xenosterols are absorbed. When more plant sterols (the major type of xenosterols) are ingested, they compete with the bulk cholesterol for solubilization, thereby reducing dietary absorption of cholesterol and lowering plasma cholesterol [4]. However, the majority of xenosterols that enter enterocytes are immediately excreted via ABCG5/G8 back into the intestinal lumen. Human subjects that fail to actively prevent xenosterol absorption develop Sitosterolemia, a monogenic recessive disorder named after the most abundant dietary xenosterol, sitosterol. The disease was first described by Bhattacharyya and Connor [35] when they identified two sisters having tendon xanthomas with normal plasma cholesterol levels and high plasma plant sterol levels. Clinically, the illness has been characterized by elevated plasma plant sterols, premature atherosclerotic disease, and tuberous tendon xanthomas [36]. The Sitosterolemia locus was later mapped to chromosome 2p21 and subsequently linked to mutations in either ABCG5 or ABCG8 genes [17,18,37].

In addition to elevated plasma sterols and xanthomas, Sitosterolemia is also characterized by hypercholesterolemia, premature cardiovascular disease, hematologic manifestations, arthritis and in rare cases hepatic failure. Hypercholesterolemia-induced premature cardiovascular disease can manifest as premature coronary heart disease or sudden cardiac death [35]. Hemolytic anemia, splenomegaly, bleeding disorders, and macrothrombocytopenia can result from the accumulation of plant sterols in platelet membranes, producing hypertrophic and hyperplasic dysfunctional platelets [36–40]. Due to similar clinical presentations, Sitosterolemia has been, in many cases, inaccurately diagnosed as familial hypercholesterolemia or idiopathic liver cirrhosis [18,41].

Mouse models of Sitosterolemia phenocopy features of the human disease, including elevated plasma xenosterols and low biliary cholesterol [32,42–45]. In addition, ABCG5/G8-deficient mice are infertile, a phenotype that is rescued by feeding a xenosterol free diet or the sterol absorption inhibitor, ezetimibe [33,42,45]. The expression of ABCG5/G8 protein is limited to the intestine, liver and gallbladder epithelium [17,32,36]. In addition to xenosterols, ABCG5/G8 mediates the final step of RCT by opposing absorption and promoting the secretion of cholesterol into the bile. Consequently, transgenic mice that overexpress the human transporters exhibit greater cholesterol elimination and are protected from atherosclerotic disease due to reduced cholesterol absorption and lower plasma cholesterol levels [46]. An ABCG5/G8 transgenic line in which expression was limited to the liver was only protected from atherosclerosis when treated with ezetimibe, indicating cooperative activity between liver and intestinal ABCG5/G8 to promote RCT [47]. Recent studies in tissue-specific ABCG5/G8-knock-out (KO) mice reveal that activity in either organ is sufficient to protect from Sitosterolemia; however, cholesterol elimination is partially compromised, suggesting reductions in RCT [48]. In 2016, Albert Groen and his colleagues reported that ABCG5/G8 is the primary sterol transporter responsible for the elimination of dietary neutral sterols through transintestinal cholesterol efflux (TICE) [49]. What remains unclear is whether ABCG5/G8 has direct selectivity between cholesterol and xenosterols. Less than 5% of dietary xenosterols are normally absorbed, while sitosterol (the primary plant sterols in diet) in Sitosterolemia patients can accumulate to 100-fold higher than controls [50,51]. The ABCG5/G8-deficient mice have shown higher accumulation of plasma xenosterols than cholesterol, nearly 300-fold increase, and the WT animals secrete xenosterols into the bile at higher rates than cholesterol [52]. In enterocytes, cholesterol is selectively esterified by acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 (ACAT2), which provides a mean of differential absorption of sterols [53,54]. However, the contribution of such ACAT2-depedent selectivity (<10-fold difference) is not enough to account for a much higher accumulation of xenosterols in patients or in model animals. It thus appears that ABCG5/G8 would play a critical role in such sterol selectivity, but a direct evidence from in vitro analyses remain to be determined.

Biosynthesis of ABCG5/G8

ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes are situated head-to-head on opposite strands and are separated by only 374 base pairs [17]. Their proximity and opposite orientation suggest that these genes share a common, bidirectional promoter and regulatory elements. The latter have been identified within the intergenic region, including the nuclear transcription factor Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 alpha (HNF4α), GATA4, and GATA6 [55]. Liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1) binding has been mapped between 134 to 142 nucleotides of the intergenic region [56]. Although no specific response elements have been identified for the Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR/NR1H4), FXR plays a prominent role in transcriptional control of ABCG5/G8 via bile acid signaling [57]. Administration of cholic acid in mice enhances ABCG5/G8 transcription, which is FXR-dependent and may be partially mediated by Fibroblast Growth Factor 15/19 (FGF15/19) and/or inhibition of Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of active B cells (NF-κB) [58–61]. Two liver X receptor (LXRα and LXRβ) response elements have also been mapped in ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes [62]. Additional transcriptional regulation includes a Forkhead Box Protein O1 (FOXO1) when insulin signaling is compromised [63]. HNF4α is thought to play a prominent role in ABCG5/G8 tissue-specific expression, which can be partially explained by epigenetic regulation. In tissues that do not express ABCG5/G8, chromatin in the regulatory region is methylated and histones are acetylated [64]. Studies of recombinant proteins in heterologous systems reveal that both ABCG5 and ABCG8 are glycosylated, depend on calnexin and calreticulin chaperones proteins for folding, and require dimerization to exit the endoplasmic reticulum [65,66]. Regulation of trafficking and activity of the mature, post-Golgi complex is poorly understood but may be regulated by bile acids, sterols, and cAMP signaling [44,62,67]. Not all ABCG5/G8 appears to reside at the cell surface, suggesting that intercellular pool may be mobilized to promote cholesterol secretion [67,68]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms that regulate the distribution and activity of the ABCG5/G8 transporter have yet to be elucidated.

Catalytic asymmetry in ABCG5/G8

Each ABC transporter comprises two nucleotide-binding composite sites, where the Walker A motif of one NBD is paired with the ABC signature motif of the other NBD [69,70]. ABCG8 contains a degenerate Walker A motif (GSSGCGRAS, RA instead of the consensus sequence KS or KT), whereas ABCG5 has a degenerate ABC signature motif (ISTGE, instead of LSGGQ/E). Therefore, one of the ATP-binding sites presents a degenerate motif, while the other presents a conserved motif, which is the only one able to support ATP hydrolysis. This catalytic asymmetry was exemplified as the functional asymmetry of biliary cholesterol secretion by using recombinant adenoviruses of ABCG5/G8 mutants in ABCG5/G8-deficient mice [71]. When Walker A or Walker B in ABCG5 was mutated, biliary sterol secretion was prevented. On the other hand, when mutating the corresponding residues in ABCG8, there was no effect on the biliary sterol secretion. In addition, mutations on the ABC signature motif of ABCG5 showed no effect on the biliary sterol secretion, as opposed to mutations of corresponding residues in ABCG8, where there was prevention in the sterol secretion [72]. As a result, these studies concluded that the conserved nucleotide-binding site was active and essential for the biliary sterol secretion.

ABCG5/G8 structure: a new molecular framework to study membrane sterol transport

A tour-de-force effort to determine the first crystal structure of sterol/cholesterol transporters: To establish the structural basis of ABCG5/G8-mediated sterol transport, we need the information on structural changes during the sterol-transport and catalytic cycles. To determine the first ABCG5/G8 structure [34], the major challenge was four-fold: (1) protein preparation, (2) crystal growth, (3) data collection of X-ray diffraction, and (4) data processing and model building. First, to obtain optimal protein preparations suitable for crystal growth, proteins had to be purified in maltose neopentyl glycol (MNG) detergents, chemically modified by cysteine alkylation and lysine methylation, and relipidated using synthetic phospholipids. MNG detergents [73], derived from alkyl maltosides, carry two long hydrocarbon chains as mimetics to phospholipids, which may contribute to better protein stability than those purified in commonly used dodecyl- or decyl-maltosides (DDM or DM). Their low critical micelle concentration (CMC) also makes it advantageous to obtain purified proteins at low detergent concentration, a critical factor of membrane protein crystallization. Second, bicelle crystallization and inclusion of cholesterol were essential in the development of crystals capable of diffracting X-ray to almost 3 Å. Third, each crystal was highly prone to X-ray radiation damage, such that a limited number of diffraction images could be collected per crystal. Several small and isomorphous datasets were thus necessary to obtain a complete dataset for structural determination. Last, no previously determined ABC transporter structures were sufficient for crystallographic phase evaluation to calculate the initial model of ABCG5/G8. Only a handful of heavy metal-derivatized crystals could be obtained to carry out anomalous diffraction analysis; de novo model building was therefore necessary. The final refinement led to the very first and experimentally determined atomic model, albeit at a modest 3.9 Å. This nevertheless provides a new and unique structural framework of ABCG5/G8 to further study its mechanism in sterol transport and reveals several never-before-seen structural motifs, which may play a critical role in determining how ABCG5/G8 (and perhaps other ABC sterol/cholesterol transporters) carry out substrate translocation through cell membranes. In the following sub-sections, we will highlight the functional implications of these structural motifs based on the above-mentioned studies in human genetics, cell and animal physiology.

Triple-helical bundles between nucleotide-binding and TMDs (Figure 1A–C): The structure of the heterodimeric ABCG5/G8 consists of an extracellular domain (ECD) that is in intimate contact with the compact TMD, and, despite the absence of ATP, the NBD maintains a tightly closed dimer. At each nucleotide-binding site, the ABC cassette and the TMD are in close proximity to a triple-helical bundle that consists of the connecting helix (CnH), the coupling helix (CpH), and the E-helix. The conserved Q-loop of ABC proteins is also located in this region. The triple-helical bundle may therefore serve as an immediate interface between NBD and TMD.

Figure 1. Structural motifs and missense variants of ABCG5/G8.

The crystal structure of ABCG5/G8 (PDB accession number: 5DO7) is plotted in cartoon presentation, with conserved amino acids colored in light orange (center). Residues whose missense mutations cause Sitosterolemia are highlighted in colors based on their maturation in cells. Green: ER-escape; red: non-ER-escape; blue: unknown. Residues whose missense mutations cause gallstone and other lipid phenotypes are plotted in gray. Only three can be localized in the current crystal structure. A540 on ABCG5 is highlighted in black. G5: ABCG5; G8: ABCG8. (A and B) The triple-helical bundle. (C) The NBDs of both subunits. (D and E) Stick presentation of the polar amino acids in the polar relay motif. (F) The ECD and the putative sterol-binding/entry site where the α-carbon of G5-A540 is highlighted in black. All figures are generated by using PyMOLTM.

TMD polar relay (Figure 1D,E): A cluster of polar amino acids are located in the transmembrane segments and on the triple-helical bundles. These amino acids are evolutionarily conserved and can form a polar relay through hydrogen bonds or salt bridges. We postulate that the TMD polar relays provide a certain degree of flexibility for the TMDs, possibly preserving favorable polar interaction within these conserved residues when proteins engage in conformational changes during sterol-transport cycles.

Putative sites for sterol binding and/or entry (Figure 1F): A vestibule configuration is formed by the ECDs and the transmembrane helices at the protein–lipid interface, and site-directed mutation of an interfacial alanine of ABCG5 (G5-A540F) blocked biliary cholesterol secretion in a transgenic mouse model [34]. This suggests the amino acid A540 is associated with sterol recognition, sterol entry, and eventual sterol translocation. Close inspection of the vestibular surface shows that several conserved aromatic amino acids are in close proximity to this area. Speculatively, this microenvironment may confer substrate specificity to cholesterol and non-cholesterol sterols.

Structural basis of ABCG5/G8 variants in Sitosterolemia and lipid phenotypes

The atomic model of ABCG5/G8 now enables us to inspect a series of missense mutations of ABCG5/G8 on the structural basis. As illustrated in Figure 1, the majority of residues that carry Sitosterolemia mutations can now be localized, and of particular note, these mutations occur mostly within the structural motifs that were first described in ABCG5/G8 structure (Table 1). In addition, polymorphic variants have been shown to cause gallstones or the elevation of LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels in the plasma [20–31]. Similarly, we can map three residues on the crystal structure, which are situated on or near the structural motifs as described above (Table 2). Therefore, knowing how these structural motifs contribute to ABCG5/G8 function will be important to further examine the mechanistic basis of the disease-causing mutations.

Table 1. Missense mutations of Sitosterolemia.

| ABCG5 | Motif | ABCG8 | Motif |

|---|---|---|---|

| E146Q | E-helix | R184H | E-helix |

| C287R | Nucleotide-binding domain | L195Q | Nucleotide-binding domain |

| R389H | TMD polar relay | P231T | Nucleotide-binding domain |

| N437K | TMD polar relay | R263Q | Nucleotide-binding domain |

| R419P | Apex of TMH2 | R405H | Connecting helix |

| R419H | Apex of TMH2 | L501P | TMD very close to the polar relay |

| R550S | Apex of TMH1 | R543S | TMD polar relay |

| L572P | Apex TMH5 | ||

| L596R | Apex TMH5 |

Table 2. Missense mutations of non-Sitosterolemia lipid phenotypes.

| Missense mutation | Motif | Lipid phenotype | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q604E | ABCG5/ECD | Gallstones High triglyceride levels low HDL-C levels |

|

| R50C | ABCG5/Unknown | Gallstones | Unresolved residue on ABCG5G8 structure model |

| V632A | ABCG8/ECD | Gallstones High LDL-C levels |

|

| T400K | ABCG8/Three-helix bundle | Gallstones High LDL-C levels |

|

| Y54C | ABCG8/Unknown | Gallstones | Unresolved residue on ABCG5G8 structure model |

| D19H | ABCG8/Unknown | Gallstones High triglyceride levels High LDL-C levels |

Unresolved residue on ABCG5G8 structure model |

Do we know the mechanism of ABCG5/G8-mediated sterol transport?

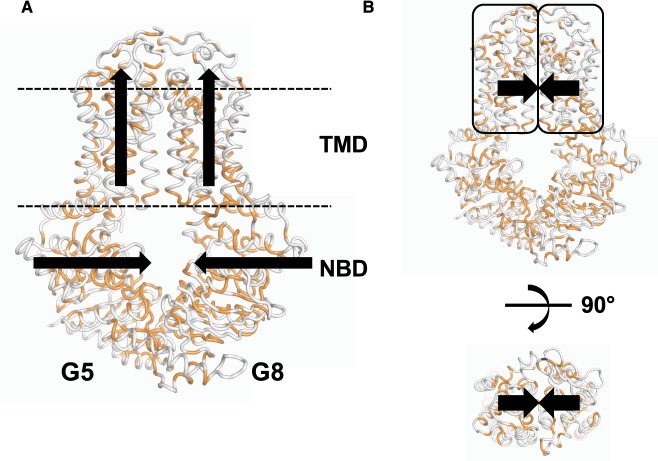

Previous physiological studies indicated the asymmetric usage of the two nucleotide-binding sites in ABCG5/G8 using mouse models [71,72] and the requirement of bile acids to stimulate cholesterol efflux using primary cells [74,75]. In vitro, the ATPase activity was shown to be responsive to bile acids, a primary component in the bile micelles [76]. The initial analysis using molecular dynamics simulation [34] suggested that a TMD upward movement and an NBD inward movement could occur simultaneously (Figure 2A). The evolution analysis showed that several co-evolved pairs, conserved but more than 8 Å apart in current apo structure (PDB accession number: 5DO7), may come in contact at another stage during the transport cycle [34]. The later suggests that the TMD of ABCG5 and that of ABCG8 may move towards each other at a certain time of the transporter function (Figure 2B). However, it is yet to be determined whether these two events in Figure 2 may occur at the same time or at different stages. It also remains unknown how ATPase activity is coupled to these predicted TMD movements. However, with the mapping of disease mutations on the newly observed structural motifs in ABCG5/G8, we can speculate that structural changes at or near these motifs may play significant roles in regulating ABCG5/G8 function. Further structural and functional studies will allow us to propose a more defined mechanism of ABCG5/G8-mediated sterol transport.

Figure 2. Trajectory of domain movement in ABCG5/G8.

(A) Molecular dynamics simulation predicted an upward movement of the TMD and inward movement of the NBD. Black arrows: movement directions. (B) Co-evolution analysis predicted conserved and co-evolved amino acid pairs in the TMDs that are >8 Å apart in the apo structure (PDB accession number: 5DO7), but will move towards each other during the transport cycle.

Perspectives

Importance of the field: Protein structures encode their functions. The structural determination of ABCG5/G8 sterol transporter opens the door to further biochemical and biophysical investigations on its structure-function relationship and the mechanistic understanding of transporter-driven sterol efflux. The new structural fold of ABCG5/G8 serves as a more relevant molecular framework to understand the mechanistic basis of cholesterol/xenosterol transport and its disease-causing variants. As exemplified by recent reports of ABCA1 and ABCG2 structures [77,78], ABCG5/G8 has also provided a new template to model functionally or structurally homologous ABC transporters.

Current thinking: The crystal structure of ABCG5/G8 in an apo state provides a structural glimpse of how the conserved structural motifs are hotspots of pathogenic mutations in ABCG5/G8. The structural motifs may also form the mechanistic basis of ABCG5/G8-mediated sterol translocation across the cell membranes. In addition to biliary sterol secretion, we now know that ABCG5/G8 regulates TICE activity in the small intestines and the LDL cholesterol levels in the plasma and that ABCG5/G8 resides on the cell surface and in the intracellular organelles to regulate secretion and storage of cholesterol and xenosterols.

Future directions: While this structural study suggested a putative sterol-binding site [34], we still lack a robust way to examine in vitro how sterols are recognized and translocated by ABCG5/G8. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop assays to further define sterol-binding and transport activities. In addition, what will need addressing in the future studies includes: (1) How exactly does ECD, triple-helical bundles or TMD polar relay participate in ABCG5/G8-mediate sterol transport and its regulation? (2) How is the signal of the ATPase activity coupled and transmitted to the movement of sterol molecules across cell membranes? (3) Through what mechanisms do ABCG5/G8 and cholesterols recognize each other and how is cellular cholesterol delivered to the transporters? (4) Under what conditions do cells ‘sense’ the need to purge excess cholesterol through ABCG5/G8? (5) How do the new findings in transcriptional and post-translational regulations control the activity of ABCG5/G8? By combining biochemical, structural, cell biology and animal physiology data, we are poised to further our understanding of the pathophysiology of biliary cholesterol secretion by ABCG5/G8 sterol transporter.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Molly de Barros, Ms. Chloé van de Panne and Dr. Bala Xavier for reading and commenting on the manuscript. This work was supported by a University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine startup grant, a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) (RGPIN 2018-04070) and a National New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada to J.-Y.L., and by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R01DK113625, R01DK100892), National Center for Research Resources (P20RR021954-05), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8P20GM103527), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117) from the National Institutes of Health to G.A.G.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- ABCG5

ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 5

- ABCG8

ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 8

- ACAT2

acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine mono-phosphate

- CMC

critical micelle concentration

- CnH

connecting helix

- CpH

coupling helix

- DDM

dodecyl-maltoside

- DM

decyl-maltoside

- ECD

extracellular domain

- FGF15/19

Fibroblast Growth Factor 15/19

- FOXO1

Forkhead Box Protein O1

- FXR

Farnesoid X Receptor

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HNF4α

Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 alpha

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LRH-1

liver receptor homolog-1

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MNG

maltose neopentyl glycol

- NBD

nucleotide-binding domain

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of active B cells

- RCT

reverse cholesterol transport

- TICE

transintestional cholesterol efflux

- TMD

transmembrane domain

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the conception of this review, as well as to the writing and approval.

Competing Interests

The Authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bloom D.E., Cafiero E.T., Jané-Llopis E., Abrahams-Gessel S., Bloom L.R., Fathima S. et al. (2011) The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases, World Economic Forum, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson R.H. (2013) Hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Prim. Care 40, 195–211 10.1016/j.pop.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steck T.L. and Lange Y. (2018) Transverse distribution of plasma membrane bilayer cholesterol: picking sides. Traffic 19, 750–760 10.1111/tra.12586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salen G., Ahrens E.H. Jr and Grundy S.M. (1970) Metabolism of beta sitosterol in man. J. Clin. Invest. 49, 952–967 10.1172/JCI106315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tall A.R., Yvan-Charvet L., Terasaka N., Pagler T. and Wang N. (2008) HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: implications for the treatment of atheroscherosis. Cell Metab. 7, 365–375 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel S.B., Graf G.A. and Temel R.E. (2018) ABCG5 and ABCG8: more than a defense against xenosterols. J. Lipid Res. 59, 1103–1113 10.1194/jlr.R084244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abumrad N.A., Sfeir Z., Connelly M.A. and Cobum C. (2000) Lipid transporters: membrane transport systems for cholesterol and fatty acids. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutri. Metab. Care 3, 255–262 10.1097/00075197-200007000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Marqués R.L., Poulsen L.R., Bailly A., Geisler M., Pomorski T.G. and Palmgren M.G. (2015) Structure and mechanism of ATP-dependent phospholipid transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1850, 461–475 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharom F.J. (2011) Flipping and flopping–lipids on the move. IUBMB Life 63, 736–746 10.1002/iub.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borst P. and Elferink R.O. (2002) Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 537–592 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xavier B.M., Jennings W.J., Zein A.A., Wang J. and Lee J.Y. (2019) Structural snapshot of the cholesterol-transport ATP-binding cassette proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol. 97, 224–233 10.1139/bcb-2018-0151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean M. and Allikmets R. (1995) Evolution of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5, 779–785 10.1016/0959-437X(95)80011-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford R.C. and Beis K. (2019) Learning the ABCs one at a time: structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 47, 23–36 10.1042/BST20180147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandzic E., Gelissen I.C., Whan R., Barter P.J., Sviridov D., Gaus K. et al. (2017) The ATP binding cassette transporter, ABCG1, localizes to cortical actin filaments. Sci. Rep. 7, 42025 10.1038/srep42025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sano O., Ito S., Kato R., Shimizu Y., Kobayashi A., Kimura Y. et al. (2014) ABCA1, ABCG1, and ABCG4 are distributed to distinct membrane meso-domains and disturb detergent-resistant domains on the plasma membrane. PLoS ONE 9, e109886 10.1371/journal.pone.0109886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savary S., Denizot F., Luciani M.-F., Mattei M.-G. and Chimini G. (1996) Molecular cloning of a mammalian ABC transporter homologous to Drosophila white gene. Mamm. Genome 7, 673–676 10.1007/s003359900203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berge K.E., Tian H., Graf G.A., Yu L., Grishin N.V., Schultz J. et al. (2000) Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science 290, 1771–1775 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee M.H., Lu K., Hazard S., Yu H., Shulenin S., Hidaka H. et al. (2001) Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat. Genet. 27, 79–83 10.1038/83799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu K., Lee M.H., Hazard S., Brooks-Wilson A., Hidaka H., Kojima H. et al. (2001) Two genes that map to the STSL locus cause sitosterolemia: genomic structure and spectrum of mutations involving sterolin-1 and sterolin-2, encoded by ABCG5 and ABCG8, respectively. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 278–290 10.1086/321294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buch S., Schafmayer C., Volzke H., Becker C., Franke A., von Eller-Eberstein H. et al. (2007) A genome-wide association scan identifies the hepatic cholesterol transporter ABCG8 as a susceptibility factor for human gallstone disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 995–999 10.1038/ng2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo K.K., Shin S.J., Chen Z.C., Yang Y.H., Yang J.F. and Hsiao P.J. (2008) Significant association of ABCG5 604Q and ABCG8 D19H polymorphisms with gallstone disease. Br. J. Surg. 95, 1005–1011 10.1002/bjs.6178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsika D., Magnusson P., Krawczyk M., Grunhage F., Lichtenstein P., Einarsson C. et al. (2010) Gallstone disease in Swedish twins: risk is associated with ABCG8 D19H genotype. J. Intern. Med. 268, 279–285 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava A., Srivastava A., Srivastava K., Choudhuri G. and Mittal B. (2010) Role of ABCG8 D19H (rs11887534) variant in gallstone susceptibility in northern India. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25, 1758–1762 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Z.Y., Cai Q. and Chen E.Z. (2014) Association of three common single nucleotide polymorphisms of ATP binding cassette G8 gene with gallstone disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e87200 10.1371/journal.pone.0087200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z.C., Shin S.J., Kuo K.K., Lin K.D., Yu M.L. and Hsiao P.J. (2008) Significant association of ABCG8:D19H gene polymorphism with hypercholesterolemia and insulin resistance. J. Hum. Genet. 53, 757–763 10.1007/s10038-008-0310-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grass D.S., Saini U., Felkner R.H., Wallace R.E., Lago W.J., Young S.G. et al. (1995) Transgenic mice expressing both human apolipoprotein B and human CETP have a lipoprotein cholesterol distribution similar to that of normolipidemic humans. J. Lipid Res. 36, 1082–1091 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kajinami K., Brousseau M.E., Ordovas J.M. and Schaefer E.J. (2004) Interactions between common genetic polymorphisms in ABCG5/G8 and CYP7A1 on LDL cholesterol-lowering response to atorvastatin. Atherosclerosis 175, 287–293 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acalovschi M., Ciocan A., Mostean O., Tirziu S., Chiorean E., Keppeler H. et al. (2006) Are plasma lipid levels related to ABCG5/ABCG8 polymorphisms? A preliminary study in siblings with gallstones. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 17, 490–494 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renner O., Lutjohann D., Richter D., Strohmeyer A., Schimmel S., Muller O. et al. (2013) Role of the ABCG8 19H risk allele in cholesterol absorption and gallstone disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 13, 30 10.1186/1471-230X-13-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Von Kampen O., Buch S., Nothnagel M., Azocar L., Molina H., Brosch M. et al. (2013) Genetic and functional identification of the likely causative variant for cholesterol gallstone disease at the ABCG5/8 lithogenic locus. Hepatology 57, 2407–2417 10.1002/hep.26009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y., Jiang Z.Y., Fei J., Xin L., Cai Q., Jiang Z.H. et al. (2007) ATP binding cassette G8 T400K polymorphism may affect the risk of gallstone disease among Chinese males. Clin. Chim. Acta 384, 80–85 10.1016/j.cca.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu L., Hammer R.E., Li-Hawkins J., von Bergmann K., Lutjohann D., Cohen J.C. et al. (2002) Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16237–16242 10.1073/pnas.252582399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu L., Gupta S., Xu F., Liverman A.D., Moschetta A., Mangelsdorf D.J. et al. (2005) Expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 is required for regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8742–8747 10.1074/jbc.M411080200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J.Y., Kinch L.N., Borek D.M., Wang J., Wang J., Urbatsch I.L. et al. (2016) Crystal structure of the human sterol transporter ABCG5/ABCG8. Nature 533, 561–564 10.1038/nature17666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharyya A.K. and Connor W.E. (1974) Beta-sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. A newly described lipid storage disease in two sisters. J. Clin. Invest. 53, 1033–1043 10.1172/JCI107640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel S.B., Honda A. and Salen G. (1998) Sitosterolemia: exclusion of genes involved in reduced cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 39, 1055–1061 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel S.B., Salen G., Hidaka H., Kwiterovich P.O., Stalenhoef A.F.H., Miettinen T.A. et al. (1998) Mapping a gene involved in regulating dietary cholesterol absorption. The sitosterolemia locus is found at chromosome 2p21. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 1041–1044 10.1172/JCI3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo E.G. (2016) Sitosterolemia: a review and update of pathophysiology, clinical spectrum, diagnosis, and management. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 1012, 7–14 10.6065/apem.2016.21.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanaji T., Kanaji S., Montgomery R.R., Patel S.B. and Newman P.J. (2013) Platelet hyperreactivity explains the bleeding abnormality and macrothrombocytopenia in a murine model of sitosterolemia. Blood 122, 2732–2743 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chase T.H., Lyons B.L., Bronson R.T., Foreman O., Donahue L.R., Burzenski L.M. et al. (2010) The mouse mutation “thrombocytopenia and cardiomyopathy” (trac) disrupts Abcg5: a spontaneous single gene model for human hereditary phytosterolemia/sitosterolemia. Blood 115, 1267–1277 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bazerbachi F., Conboy E.E., Mounajjed T., Watt K.D., Babovic-vuksanovic D., Patel S.B. et al. (2017) Cryptogenic cirrhosis and sitosterolemia: a treatable disease if identified but fatal if missed. Ann. Hepatol. 16, 970–978 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solca C., Tint G.S. and Patel S.B. (2013) Dietary xenosterols lead to infertility and loss of abdominal adipose tissue in sterolin-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 54, 397–409 10.1194/jlr.M031476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plosch T., Bloks V.W., Terasawa Y., Berdy S., Siegler K., van der Sluijs F. et al. (2004) Sitosterolemia in ABC-Transporter G5-deficient mice Is aggravated on activation of the liver-X receptor. Gastroenterology 126, 290–300 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klett E.L., Lu K., Kosters A., Vink E., Lee M., Altenburg M. et al. (2004) A mouse model of sitosterolemia: absence of Abcg8/sterolin-2 results in failure to secrete biliary cholesterol. BMC Med. 2, 5 10.1186/1741-7015-2-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDaniel A.L., Alger H.M., Sawyer J.K., Kelley K.L., Kock N.D., Brown J.M. et al. (2013) Phytosterol feeding causes toxicity in ABCG5/G8 knockout mice. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 1131–1138 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilund K.R., Yu L., Xu F., Hobbs H.H. and Cohen J.C. (2004) High-level expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 attenuates diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in Ldlr −/− mice. J. Lipid Res. 45, 1429–1436 10.1194/jlr.M400167-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basso F., Freeman L.A., Ko C., Joyce C., Amar M.J., Shamburek R.D. et al. (2007) Hepatic ABCG5/G8 overexpression reduces apoB-lipoproteins and atherosclerosis when cholesterol absorption is inhibited. J. Lipid Res. 48, 114–126 10.1194/jlr.M600353-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J., Mitsche M.A., Lütjohann D., Cohen J.C., Xie X.S. and Hobbs H.H. (2015) Relative roles of ABCG5/ABCG8 in liver and intestine. J. Lipid Res. 56, 319–330 10.1194/jlr.M054544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jakulj L., van Dijk T.H., de Boer J.F., Kootte R.S., Schonewille M., Paalvast Y. et al. (2016) Transintestinal cholesterol transport is active in mice and humans and controls ezetimibe-induced fecal neutral sterol excretion. Cell Metab. 24, 783–794 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salen G., Shore V., Tint G.S., Forte T., Shefer S., Horak I. et al. (1989) Increased sitosterol absorption, decreased removal, and expanded body pools compensate for reduced cholesterol synthesis in sitosterolemia with xanthomatosis. J. Lipid Res. 30, 1319–1330 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salen G., Shefer S., Nguyen L., Ness G.C., Tint G.S. and Shore V. (1992) Sitosterolemia. J. Lipid Res. 33, 945–955 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu L., von Bergmann K., Lutjohann D., Hobbs H.H. and Cohen J.C. (2004) Selective sterol accumulation in ABCG5/ABCG8-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 45, 301–307 10.1194/jlr.M300377-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klett E.L. and Patel S. (2003) Genetic defenses against noncholesterol sterols. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 14, 341–345 10.1097/01.mol.0000083763.66245.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen T.M., Sawyer J.K., Kelley K.L., Davis M.A., Kent C.R. and Rudel L.L. (2012) ACAT2 and ABCG5/G8 are both required for efficient cholesterol absorption in mice: evidence from thoracic lymph duct cannulation. J. Lipid Res. 53, 1598–1609 10.1194/jlr.M026823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sumi K., Tanaka T., Uchida A., Magoori K., Urashima Y., Ohashi R. et al. (2007) Cooperative interaction between hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha and GATA transcription factors regulates ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4248–4260 10.1128/MCB.01894-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freeman L.A., Kennedy A., Wu J., Bark S., Remaley A.T., Santamarina-Fojo S. et al. (2004) The orphan nuclear receptor LRH-1 activates the ABCG5/ABCG8 intergenic promoter. J. Lipid Res. 45, 1197–1206 10.1194/jlr.C400002-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J., Einarsson C., Murphy C., Parini P., Björkhem I., Gåfvels M. et al. (2006) Studies on LXR-and FXR-mediated effects on cholesterol homeostasis in normal and cholic acid-depleted mice. J. Lipid Res. 47, 421–430 10.1194/jlr.M500441-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamisako T., Ogawa H. and Yamamoto K. (2007) Effect of cholesterol, cholic acid and cholestyramine administration on the intestinal mRNA expressions related to cholesterol and bile acid metabolism in the rat. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22, 1832–1837 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu J., Lu H., Lu Y., Lei X., Cui J.Y., Ellis E. et al. (2014) Potency of individual bile acids to regulate bile acid synthesis and transport genes in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol. Sci. 141, 538–546 10.1093/toxsci/kfu151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balasubramaniyan N., Ananthanarayanan M. and Suchy F.J. (2016) Nuclear factor-(B regulates the expression of multiple genes encoding liver transport proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 310, G618–G628 10.1152/ajpgi.00363.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Byun S., Jung H., Chen J., Kim Y.C., Kim D.H., Kong B. et al. (2019) Phosphorylation of hepatic farnesoid X receptor by FGF19 signaling-activated Src maintains cholesterol levels and protects from atherosclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 8732–8744 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Back S.S., Kim J., Choi D., Lee E.S., Choi S.Y. and Han K. (2013) Cooperative transcriptional activation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes by nuclear receptors including liver-X-Receptor. BMB Rep. 46, 322–327 10.5483/bmbrep.2013.46.6.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Biddinger S.B., Haas J.T., Yu B.B., Bezy O., Jing E., Unterman T.G. et al. (2008) Hepatic insulin resistance directly promotes formation of cholesterol gallstones. Nat. Med. 14, 778–782 10.1038/nm1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imai S., Kikuchi R., Kusuhara H., Yagi S. and Shiota K. (2009) Analysis of DNA methylation and histone modification profiles of liver-specific transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 568–576 10.1124/mol.108.052589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graf G.A., Cohen J.C. and Hobbs H.H. (2004) Missense mutations in abcg5 and abcg8 disrupt heterodimerization and trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24881–24888 10.1074/jbc.M402634200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hirata T., Okabe M., Kobayashi A., Ueda K. and Matsuo M. (2009) Molecular mechanisms of subcellular localization of ABCG5 and ABCG8. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 619–626 10.1271/bbb.80694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamazaki Y., Yasui K., Hashizume T., Suto A., Mori A., Murata Y. et al. (2015) Involvement of a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent signal in the diet-induced canalicular trafficking of adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter g5/g8. Hapatology 62, 1215–1226 10.1002/hep.27914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guyot C. and Stieger B. (2011) Interaction of bile salts with rat canalicular membrane vesicles: evidence for bile salt resistant microdomains. J. Hepatol. 55, 1368–1376 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yuan Y.R., Blecker S., Martsinkevich O., Millen L., Thomas P.J. and Hunt J.F. (2001) The crystal structure of the MJ0796 ATP-binding cassette. Implications for the structural consequences of ATP hydrolysis in the active site of an ABC transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32313–32321 10.1074/jbc.M100758200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karpowich N., Martsinkevich O., Millen L., Yuan Y.R., Dai P.L., MacVey K. et al. (2001) Crystal structures of the MJ1267 ATP binding cassette reveal an induced-fit effect at the ATPase active site of an ABC transporter. Structure 9, 571–586 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00617-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang D.W., Graf G.A., Gerard R.D., Cohen J.C. and Hobbs H.H. (2006) Functional asymmetry of nucleotide-binding domains in ABCG5 and ABCG8. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4507–4516 10.1074/jbc.M512277200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang J., Grishin N., Kinch L., Cohen J.C., Hobbs H.H. and Xie X.S. (2011) Sequences in the nonconsensus nucleotide-binding domain of ABCG5/ABCG8 required for sterol transport. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7308–7314 10.1074/jbc.M110.210880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chae P.S., Rasmussen S.G.F., Rana R., Gotfryd K., Chandra R., Goren M.A. et al. (2010) Maltose-neopentyl glycol (MNG) amphiphiles for solubilization, stabilization and crystallization of membrane proteins. Nat. Methods 7, 1003–1008 10.1038/nmeth.1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vrins C., Vink E., Vandenberghe K.E., Frijters R., Seppen J. and Groen A.K. (2007) The sterol transporting heterodimer ABCG5/ABCG8 requires bile salts to mediate cholesterol efflux. FEBS Lett. 581, 4616–4620 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tachibana S., Hirano M., Hirata T., Matsuo M., Ikeda I., Ueda K. et al. (2007) Cholesterol and plant sterol efflux from cultured intestinal epithelial cells is mediated by ATP-binding cassette transporters. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 1886–1895 10.1271/bbb.70109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson B.J., Lee J.Y., Pickert A. and Urbatsch I.L. (2010) Bile acids stimulate ATP hydrolysis in the purified cholesterol transporter ABCG5/G8. Biochemistry 49, 3403–3411 10.1021/bi902064g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qian H., Zhao X., Cao P., Lei J., Yan N. and Gong X. (2017) Structure of the human lipid exporter ABCA1. Cell 169, 1228–1239 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taylor N.M.I., Manolaridis I., Jackson S.M., Kowal J., Stahlberg H. and Locher K.P. (2017) Structure of the human multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature 546, 504–509 10.1038/nature22345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]