Abstract

Background

The health status and needs of indigenous populations of Australia, Canada and New Zealand are often compared because of the shared experience of colonisation. One enduring impact has been a disproportionately high rate of commercial tobacco use compared with non-indigenous populations. All three countries have ratified the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which acknowledges the harm caused to indigenous peoples by tobacco.

Aim and objectives

We evaluated and compared reporting on FCTC progress related to indigenous peoples by Australia, Canada and New Zealand as States Parties. The critiqued data included disparities in smoking prevalence between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples; extent of indigenous participation in tobacco control development, implementation and evaluation; and what indigenous commercial tobacco reduction interventions were delivered and evaluated.

Data sources

We searched FCTC: (1) Global Progress Reports for information regarding indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand; and (2) country-specific reports from Australia, Canada and New Zealand between 2007 and 2016.

Study selection

Two of the authors independently reviewed the FCTC Global and respective Country Reports, identifying where indigenous search terms appeared.

Data extraction

All data associated with the identified search terms were extracted, and content analysis was applied.

Results

It is difficult to determine if or what progress has been made to reduce commercial tobacco use by the three States Parties as part of their commitments under FCTC reporting systems. There is some evidence that progress is being made towards reducing indigenous commercial tobacco use, including the implementation of indigenous-focused initiatives. However, there are significant gaps and inconsistencies in reporting. Strengthening FCTC reporting instruments to include standardised indigenous-specific data will help to realise the FCTC Guiding Principles by holding States Parties to account and building momentum for reducing the high prevalence of commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples.

Keywords: Disparities, Human Rights, Priority/special Populations, Surveillance And Monitoring

Introduction

Indigenous peoples experience an alarmingly high burden of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.1 2 While some indigenous peoples have traditionally used tobacco for ceremonial or sacred purposes, it is increasingly recognised that the use of commercial tobacco (produced for recreational use by for-profit companies using processed leaf and chemical additives) is a major factor in indigenous health inequities.2–4

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which came into force in 2005, is an international treaty that recognises the disproportionate harm caused by commercial tobacco to indigenous peoples. The FCTC includes a preamble, guiding principles and extensive commentary on tobacco control measures and associated activities. The Preamble states that Parties are ‘Deeply concerned about the high levels of smoking and other forms of tobacco consumption by indigenous peoples’ (FCTC, Preamble)2 (p. 2). It also acknowledges the evidence for tobacco-related harms, the increase of tobacco consumption by women and girls, the threat posed by advertising and promotion, illicit trade and the need for cooperative action to reduce commercial tobacco use.2 The FCTC requires each Party to submit regular reports on progress towards their respective obligations.2 5 Where practicable, indicators for the aforementioned areas are included within the FCTC reporting Core Instrument.

This paper evaluates reporting under the FCTC between 2007 and 2016 on commercial tobacco use and FCTC progress on tobacco control regarding indigenous peoples. As outlined in the FCTC, and in alignment with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,6 such data could document and monitor how indigenous peoples have participated in the design, implementation and evaluation of commercial tobacco reduction interventions; providing evaluation data on general and indigenous specific interventions for indigenous peoples; and documenting commercial tobacco use. The influence of FCTC reporting results in various incentives and pressures to improve tobacco control, demonstrating tobacco control achievements and areas for improvement. FCTC reporting recognises Parties’ accountability, particularly to indigenous peoples, domestically and internationally through their obligations as WHO Members. Ultimately, the value of the FCTC is whether this leads to better tobacco control, reduced commercial tobacco use and consequently reduced burden of tobacco related harms to reaffirm the right of all people to the highest standard of health.2 It is thus timely to consider what FCTC progress has been reported to reduce commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples in acceding countries. This provides opportunities to reduce commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples, sharing the findings among ratified and non-ratified countries.

Background

The WHO estimates that tobacco use will cause 8 million deaths annually by 2030.7 While many countries have indigenous populations, Australia, Canada, New Zealand (Aotearoa) and the USA are often seen as natural comparators in relation to indigenous health. For the purposes of this paper, we have focused on indigenous peoples located within three high-income countries with ongoing experiences of colonisation: Australia, Canada and New Zealand. These countries have ratified the FCTC, while the USA has not ratified the FCTC. Thus, the USA cannot be included in this study. Furthermore, these countries have similar gross national income per capita, political environments, legislative frameworks and colonial histories. They also consistently place near the top of the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Index rankings.8 Australia, Canada and New Zealand’s colonial histories have limited indigenous peoples’ participation in decision making and have indigenous populations who experience poorer health outcomes than their non-indigenous counterparts.8

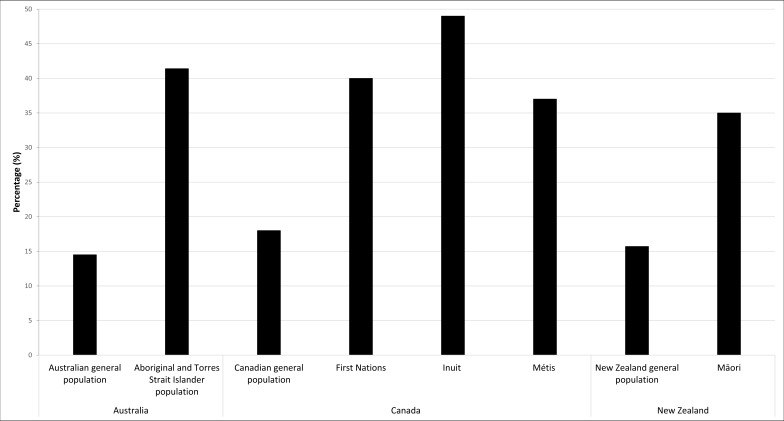

Smoking prevalence has declined among the general population in many high-income countries, including Australia, Canada and New Zealand.9 This includes recent declines in commercial tobacco use among indigenous populations in Australia and New Zealand.1 10 11 However, the prevalence of commercial tobacco use between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples continues to be disparate.1 10–12 The prevalence of commercial tobacco use (figure 1) in the general population of Australia, Canada and New Zealand is 16%, 18% and 16% respectively.10–14 Data suggest prevalence of commercial tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (41%), First Nations (40%), Inuit (49%) and Métis (37%) peoples in Canada and Māori peoples in New Zealand (35%)11 is substantially higher than their non-indigenous counterparts.

Figure 1.

Commercial tobacco use in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by indigenous population and the general population.

Research suggests that some of the drivers associated with commercial tobacco use are similar for indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.15 16 For example, socioeconomic status (SES) is strongly linked to smoking.17 Indigenous populations overall report lower SES, increasing the risk of commercial tobacco use and consequently experiencing tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.17 For indigenous peoples, lower SES is an outcome that has impacted over generations through the mechanics of colonisation that have eroded power, social structures and indigenous community resources.18–20 The erosion of social structures and intergenerational connectedness with associated impacts and added stressors resulting from colonisation have directly and indirectly impacted commercial tobacco use.15 16 20 21 Commercial tobacco was used as a form of payment, with tobacco issued as rations on missions in Australia.22–24 In Canada, ceremonial practices such as ceremonial tobacco use were illegal under amendments to the Indian Act of 1885, but commercial tobacco use was not, which prompted the use of commercial tobacco use.20 24

The FCTC recognises the needs and challenges experienced by indigenous peoples, and the importance of facilitating indigenous leadership and participation in developing, implementing and evaluating commercial tobacco reduction interventions.2 Numerous countries with indigenous populations are Parties to the FCTC, including Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Given the FCTC indigenous clauses and broader reporting commitments, Parties with indigenous populations could expect the need to consistently collect and report: high-quality data that are accurate and comprehensively cover areas of commercial tobacco use and are comparable across countries to allow comparisons. The first FCTC report was compiled in 2007 and covered the initial 2-year period after the FCTC was enacted. The WHO developed a standard reporting template and a compendium of indicators.5 Reports were compiled between 2007 and 2016. FCTC reports are available to review as summary Global Progress Reports across all parties or as individual country reports.5

Aim and objectives

This study evaluates FCTC reporting of progress made in relation to indigenous obligations in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. We specifically examined:

Whether indigenous data were being reported in relation to indigenous peoples, including any disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous commercial tobacco use.

The extent of indigenous participation in commercial tobacco intervention development, implementation and evaluation.

If indigenous commercial tobacco reduction interventions were being delivered and evaluated under the FCTC.

Methods

Search strategy

We undertook a two-pronged search of: (1) all Global Progress Reports on implementation of the FCTC from its commencement (2007–2016) for information regarding indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and (2) FCTC country-specific reports from Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Search terms

To address the study’s aims and identify indigenous-reported activities, achievements, innovative approaches and ‘wise practices’25 (p. 7), we searched each report for ‘Indigenous’ search terms (search strategy is available on request). The search terms were intended to capture references to indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. To ensure any references to indigenous peoples in Canada were identified, the search included indigenous terms used throughout North America. This included terms used in USA, although it has not ratified the FCTC and is not included in this study. The term ‘Ethnic’ was also used as a search term due to the FCTC reporting template including an ’ethnic' data collection field but not including an indigenous specific data collection field. Any references to ‘ethnic’ in the results are where it is clearly in reference to indigenous peoples.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (RM and AW) with lived indigenous experience and expertise in indigenous commercial tobacco control independently reviewed the FCTC Global and Country specific reports to identify where search terms appeared.

Data synthesis

We applied conventional content analysis to the extracted data.26 Two authors (RM and AW) independently coded all included FCTC reports. Both authors independently identified many of the same codes, so consensus was reached quickly. Preliminary themes were shared with all authors to assist in the validation process. No substantive changes were recommended. This approach was well suited to the broad and sometimes inconsistent scope and terminology of reporting across Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Content analysis was applied to capture and synthesise the diverse evidence, identifying and textually describing meaningful patterns and themes.26

Results

Indigenous data, including any disparities in commercial tobacco use

The results are reported by: (1) Global Progress Reports, and (2) Country specific reports: Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Global Progress Reports results

Seven Global Progress Reports from 2007 to 2016 were searched. Search terms were identified in the 2010, 2012 and 2014 Global Reports (table 1).

Table 1.

Reference to indigenous or ethnicity in FCTC Global Progress Reports by year

| Year* | Indigenous reference and data |

| 2007 | No references, no data in FCTC reports. |

| 2008 | No references, no data in FCTC reports. |

| 2009 | No references, no data in FCTC reports. |

| 2010 | Reference to disparities in smoking prevalence by ethnicity in New Zealand, which ranged between 12% and 45% (p. 46). The 45% smoking prevalence referred to the Māori daily smoking rate. |

| 2012 | References to indigenous peoples for Australia, New Zealand, Ecuador, Guatemala and Paraguay, including reporting smoking prevalence compared with the general population. Use of the term ‘ethnicity’ was recognised as being inconsistently applied across Parties. |

| 2014 | References to ‘indigenous’ were limited to Australia in relation to a programme for indigenous (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) populations and New Zealand indigenous (Māori) females having higher smoking prevalence than males. Use of the term ‘ethnicity’ was inconsistently applied across parties. There was also reference to higher smoking in ‘specific ethnic groups’ in Australia, Benin, Italy, Kazakhstan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, New Zealand, Singapore and Spain. |

| 2016 | No references to ‘indigenous’ groups. Thirty-four FCTC parties (26%) indicated they had data for commercial tobacco use by ethnic groups. |

*Progress reporting moved from annual to biennial after 2010.

FCTC, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Country reports: Australia, Canada and New Zealand

The information reported by Australia, Canada and New Zealand was diverse, although each country was relatively consistent in their respective reporting over time. Using content analysis, the following themes emerged: (1) smoking prevalence, (2) commentary on targets and strategies that were expected to impact indigenous commercial tobacco use, (3) descriptions of programmes, services and policies and (4) commentary on indigenous participation in the development and implement of commercial tobacco control activities (table 2). Australia consistently provided details on prevalence and indigenous commercial tobacco reduction programmes and strategies; Canada detailed information regarding illicit or smuggled commercial tobacco; and New Zealand outlined Smoke-free Environments Regulations 2007, including Māori language health warning and the goal of ‘reducing smoking prevalence and commercial tobacco availability to minimal levels by 2025’.

Table 2.

indigenous reporting themes in country-specific reports of Australia, Canada and New Zealand

| Indigenous-specific references: | Australia | Canada | New Zealand |

| 2007 | |||

| Prevalence | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Targets, aims or objectives | |||

| Programme and policy descriptions | ☑ | ||

| Illicit trade | ☑ | ||

| Taxation | ☑ | ||

| 2009 | |||

| Prevalence | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Targets, aims or objectives | |||

| Programme and policy description/s | ☑ | ||

| Illicit trade | ☑ | ||

| Taxation | |||

| 2012 | |||

| Prevalence | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Targets, aims or objectives | ☑ | ||

| Programme and policy description/s | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| Illicit trade | ☑ | ||

| Taxation | |||

| 2014 | |||

| Prevalence | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Targets, aims or objectives | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Programme and policy description/s | ☑ | ||

| Illicit trade | ☑ | ||

| Taxation | |||

| 2016 | |||

| Prevalence | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Targets, aims or objectives | ☑ | ☑ | |

| Programme and policy description/s | ☑ | ||

| Illicit trade | ☑ | ||

| Taxation | |||

Smoking prevalence

Australia and New Zealand consistently reported smoking prevalence (table 3). Canada did not report prevalence of commercial tobacco use among First Nations (status or non-status),27 Inuit or Métis populations.

Table 3.

Reported indigenous smoking prevalence: Australia, Canada and New Zealand

| Australia (15 years and over) |

Canada | New Zealand | |

| 2007 |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

Daily use: 50%. Occasional use: 2%. |

Not reported in FCTC reports. |

Māori (2006): Daily use: 43%. Occasional use: 2%. |

| 2009 |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

Total: 47%. |

Not reported in FCTC reports. |

Māori: Daily use Male: 40.4%. Female: 49.7%. Total: 45.4%. |

| 2012 |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

Total: 47%. |

Not reported in FCTC reports. |

Māori: Daily use Male: 40.2%. Female: 49.3%. Total: 45.1%. |

| 2014 |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

Male: 44.6%. Female: 41.4%. Total: 43%. |

Not reported in FCTC reports. |

Māori: Daily use Male: 36.4%. Female: 41.8%. Total: 39.2%. |

| 2016 |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

Male: 44.6%. Female: 41.4%. Total: 43%. |

Not reported in FCTC reports. |

Māori:

Daily use Male: 34.4%. Female: 41.8%. Total: 38.1%. |

Indigenous participation

Only Australia explicitly referred to indigenous peoples participating in the development and implementation of tobacco control interventions. The Tackling Indigenous Smoking measure, led by the National Coordinator Tackling Indigenous Smoking, was implemented and included a national network of Regional Tobacco Coordinators and Tobacco Action Workers. Workers were engaged through Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations where practicable to increase awareness of commercial tobacco harms and facilitate smoking prevention and cessation programmes. The network had access to funding and materials to conduct local community-based social marketing campaigns and community events and the provision of training (2012, 2014 and 2016). Australian reports also referred to the Victorian State Best Practice Forum for Aboriginal Tobacco Control, which brought together stakeholders to share their experiences and ideas on how to reduce tobacco-related harm (2016).

Canada and New Zealand made indirect references to indigenous peoples’ participation in tobacco control. In Canada, the reports referred to First Nations and Inuit Health and the Public Health Agency of Canada providing input into the development of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016). This strategy promoted smoking cessation among the First Nations, Inuit and Métis populations. In New Zealand reports, the Māori Affairs Select Committee inquiry into the harm caused to Māori by commercial tobacco was discussed. This committee included Māori members of Parliament and advisors who received submissions from individuals and organisations, including those representing Māori interests.

Indigenous commercial tobacco reduction interventions under the FCTC

Targets, aims or objectives

Australia, Canada and New Zealand expressed commitments to reducing smoking prevalence among the respective indigenous populations. Australia and New Zealand described targets they were aiming to achieve, while Australia also described strategies to address commercial tobacco use among the indigenous population. The Australian reports described the National Tobacco Strategy 2012–2018 that included an objective to halve the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult daily smoking rate by 2018, over the 2009 baseline (from 47%). The Strategy recognised the social and health inequalities associated with commercial tobacco use and emphasised the importance of working in partnership to reduce smoking rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (2014 and 2016). Reports from Canada referred to the Coordinated Effort to Effectively Address Tobacco Control in First Nations Communities and the Inuit Tobacco Reduction Strategy (2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016).

New Zealand described an official Parliament Māori Affairs Select Committee hearing that recommended 42 actions to reduce the harm caused by tobacco to Māori (2012). The Government generally accepted the recommendations, including the adoption of the goal that New Zealand should be ‘essentially’ smoke free by 2025 (2012). Interim targets were set, including halving the daily smoking prevalence among Māori by 2018, from their 2011–2012 levels (2014 and 2016).

Programme, service and policy descriptions

Each country described to varying degrees programmes, services and policies to address commercial tobacco use among the respective indigenous populations. We identified commercial tobacco control interventions delivered as part of general population campaigns (with aspects prioritising indigenous populations) and programmes, services and policies designed specifically for indigenous peoples.

General population interventions

Types of general population interventions that included indigenous components and were common across at least two countries were: national and local mass communication/public awareness campaigns (Australia and Canada); commercial tobacco package health warnings (Australia and New Zealand); and reducing illicit trade (Canada and New Zealand). Australia consistently reported education, communication and public awareness campaigns being implemented at federal, state, territory, regional and local levels (2007, 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016 reports). While Canada outlined partnerships between Health Canada and their First Nations and Inuit partners to reduce commercial tobacco use, and a partnership with the Cancer Society to get young people talking about smoking, quitting and remaining smoke free (2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016). In relation to health warnings, New Zealand (2009, 2012 and 2014) made specific reference to the inclusion of Māori text (along with English) with new pictorial health warnings on tobacco packaging.

References to illicit trade in Canadian reports (2007, 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016) identified First Nations communities as sources of illicit commercial tobacco. The reports noted that a key source of illicit commercial tobacco was fully equipped industrial plants located in First Nations communities. Furthermore, manufacturing operations located on tribal lands in the USA were described as supplying the majority of the illicit market for commercial tobacco products (2007). The reports also described an increasing number of ‘Smoke Shacks’ on some First Nation reserve lands, which were designed for large volume cigarette sales and were seen as distributors for the underground market (2007). Canadian reports also detail a special unit of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Anti-Contraband Tobacco Force, which was established to address illicit trade, along with a ‘Trafficking in Contraband Tobacco Act’ and funding for First Nations police services to target contraband commercial tobacco (2014 and 2016). New Zealand references to illicit trade and Māori were made in the context of commercial tobacco products in the New Zealand market requiring Māori language health warnings. This helped to determine if products were legal or illicit (2009, 2012 and 2014).

Australia reported on general population interventions that were seen as being effective for indigenous populations. These were the introduction of plain packaging (2012), enhancing Quitlines to be responsive to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander needs (2012, 2014 and 2016) and implementing Nicotine Replacement Therapy interventions (2007, 2012 and 2016) for eligible Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (2012).

Indigenous-specific interventions

Only Australia and Canada described indigenous-specific policy and programmes. Both countries commented on the development of cessation services for indigenous populations. The Australian reports described smoking cessation resources and training (eg, brief intervention training) that were developed and implemented for people working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including Aboriginal Health Workers (2007, 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016) and a smoking cessation programme for Aboriginal mothers (2009).

In addition, Australian reports described comprehensive public health packages to address Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking (2012, 2014 and 2016) and an Indigenous Tobacco Control Initiative, which piloted innovative approaches to reduce smoking (2012).

Discussion

The FCTC continues to influence the global tobacco control agenda and has the potential to drive action. Improved FCTC reporting would enable Parties to better recognise their accountability due to increased transparency. The FCTC obligates parties to implement measures that reduce tobacco harm within their respective countries and collectively, working against the tobacco epidemic at a global level. Reducing the disproportionate tobacco-related harm among indigenous peoples is also implied in the FCTC Preamble and an important requirement of those countries with colonial histories.2 For the countries included in this analysis, we found marked variation in how they have reported progress to address tobacco-related harms among indigenous peoples.

Our first aim was to explore whether indigenous data were being reported, including any disparities in commercial tobacco use between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. Overall, this assessment found variation in how Australia, Canada and New Zealand reported progress to address tobacco-related harms among indigenous peoples. We found inconsistent use of terminology and measures across the three countries. For example, the term ‘ethnic’ was sometimes applied to peoples of non-European descent, in general, and at other times specifically to indigenous populations. This limits the ability to identify, compare and share achievements and challenges of indigenous peoples, as well as accurately measure changes in commercial tobacco use or highlight any disparities. Furthermore, only Australia and New Zealand reported smoking prevalence within the respective indigenous populations. These countries reported decreasing trends in indigenous smoking prevalence respectively (Australia and New Zealand 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016). However, smoking prevalence remained alarmingly high and at least double the rate of the respective non-indigenous populations (Australia and New Zealand 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016). Collecting and reporting these data are an essential means of monitoring success (or otherwise) in reducing smoking disparities and the overall progress towards FCTC goals. Furthermore, there were no references to indigenous peoples in any of the Global Progress Reports over the first three reporting periods. This is a missed opportunity to create international reporting of indigenous baseline data and context-specific factors critical to the tobacco control landscape such as indigenous-focused interventions. As a result, indigenous peoples have been relatively ‘invisible’ in terms of limited monitoring and having the ability to compare factors over time. However, Australia and New Zealand have long-standing, relatively high-quality monitoring systems (while acknowledging limitations, such as indigenous identifier misclassification and sampling bias) that include data on indigenous tobacco use.

Our second aim sought to determine the extent to which indigenous peoples were reported to be participating in the development, implementation and evaluation of tobacco control initiatives. Indigenous engagement will help develop ownership over interventions and assists to ensure conception and implementation in an appropriate and effective manner. Two notable participatory mechanisms were the Tackling Indigenous Smoking programme in Australia. This programme sought federal-level, state-level and local-level planning and coordination of tobacco control activity for and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. A second mechanism was the Māori Affairs Select Committee inquiry in New Zealand on the impact of smoking on Māori. All three countries included some comment on indigenous participation within the planning and delivery of their respective tobacco control programmes. However, participation tended to be described in relation to specific aspects (such as cessation services), and it was not clear when describing the extent of indigenous participation throughout a country’s tobacco control programme. It would be useful to report on indigenous engagement in legislative interventions that affect the entirety of the population and have the potential for equitable impacts across subpopulations. For example, whether indigenous peoples participated in the development of tobacco tax regimes or the introduction of standardised packaging.

Our final aim was to examine if indigenous-focused interventions to reduce the use of commercial tobacco products were being delivered and evaluated. No evaluative information was provided in FCTC reports regarding actual or potential impacts of general or indigenous specific tobacco reduction interventions. Without such information, it is not possible to assess whether interventions were having direct or indirect impacts on indigenous smoking prevalence, and there are limited opportunities for other countries to learn from their experiences.

Data on indigenous interventions was available, for example, Minichiello et al’s reported effective strategies to reduce commercial tobacco use in indigenous communities.4 The review identified 42 interventions in Australia (n=19), Canada (n=14), New Zealand (n=8) andAustralia and New Zealand (n=1) published between 2005 and 20154 that aimed to prevent, reduce and/or cease the use of commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples. Given the availability of data, this information could be more fully captured by more appropriate FCTC reporting instruments, providing opportunities to share and learn from tobacco control experiences.

Another omission from the FCTC reports was the prevalence of commercial tobacco use among First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Canada is generally known for excellence in quality and relevance of its health statistics.14 However, as Smylie and Firestone14 demonstrated, indigenous data quality issues such as non-response and bias misclassification errors contribute to significantly underestimating health inequities between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. While acknowledging these data quality limitations,14 we also note that the prevalence of commercial tobacco use among First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples have been reported elsewhere.12 Therefore, and as outlined in the limitations, care should be taken when considering these findings as the FCTC reporting may not accurately capture and reflect what is actually happening in relation to tobacco control among to indigenous peoples under the FCTC. We also note that this may reflect some complexity and dynamic nature of indigenous tobacco control and the disconnect between reporting agencies and their respective indigenous tobacco control communities.

Australia, Canada and New Zealand have expressed commitments to reducing the use of commercial tobacco products among indigenous populations; however, only Australia and New Zealand commented on specific smoking targets. Canadian reports commented on the development of a First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy in 2006,28 29 although it appears this strategy has not eventuated.

All three countries also described general population interventions that were expected to impact indigenous commercial tobacco use. Types of general population interventions that were expected to make a significant impact on indigenous smoking varied across the countries. At least two described mass communications campaigns delivered at national and/or local levels (Australia and Canada), health warnings (Australia and New Zealand) and illicit trade (Canada and New Zealand). However, the commentary around illicit trade within Canada was unique, identifying this as a ‘problem’ within indigenous communities, highlighting the inclination to ‘problematise’ indigenous peoples. Only two countries (Australia and Canada) described indigenous specific interventions, and these mainly focused on the development and delivery of cessation services.

While some progress has been made, there is significant scope for improving how country and global reports share FCTC progress towards reducing commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples. Opportunities for improving reporting include: improving consistent use of definitions and measures; reporting on how indigenous peoples are participating throughout tobacco programmes and policies; and supporting the evaluation of indigenous specific and general population tobacco control interventions with a focus on effectiveness and smoking prevalence. There are at least two inter-related mechanisms through which these opportunities could be realised: (1) the WHO could provide leadership on FCTC Parties reporting in relation to indigenous commercial tobacco use and (2) Parties could use indigenous leadership and expertise in relation to wise practices in working with indigenous peoples in tobacco control.

In relation to the first mechanism, a key issue is inherent within the reporting templates provided for the ‘Core’ and ‘Additional Questions’. There are currently no specific expectations for Parties to report on commercial tobacco use among theindigenous populations. This is likely to have contributed to the inconsistent and probable under-reporting regarding tobacco control and indigenous peoples. For example, the Core Instrument Section 2.1.5 asks countries to report smoking rates within various subpopulations, including ethnic groups.5 However, the definition of ‘ethnic’ is ambiguous, and indigenous peoples are treated in a similar manner to other ‘ethnic’ groups.5 There are also questions in the instrument about whether legislation has been passed that bans smoking in indoor workplaces, public transport and public spaces (section 3.2.2).5 A follow-up question asks whether this legislation has been implemented in ‘cultural facilities’. In the template, there are no opportunities to distinguish whether these facilities are associated with indigenous peoples and ethnic groups or to describe the respective community engagement in the development of the legislation.5 29 Section 3.2.6 explores whether a Party has implemented educational and public awareness tobacco control programmes. This includes prompts to elicit whether ethnic groups are targeted by these programmes or if cultural differences were taken into account.5 However, the ethnic groups targeted or the cultural differences acknowledged cannot be indicated within the template. Questions also seek to establish what types of agencies and non-government organisations were involved in the ‘… development and implementation of intersectoral programmes and strategies for tobacco control’. Furthermore, an ‘other (please specify)’ category is offered for organisations not listed, but there is no specific reference to indigenous engagement or any indigenous prompt.5

Supporting indigenous engagement in tobacco control activity is specifically referenced in the FCTC, under Article 4 of the Guiding Principles. As a Guiding Principle, it would be expected that all Articles of the FCTC are relevant for indigenous peoples. To this end, additional fields could be added to the ‘Additional Questions’ template that sit alongside the existing Core template questions that elicit information and explore relevant topics including: indigenous exposure to secondhand smoke; tobacco related mortality; the economic burden on indigenous peoples due to commercial tobacco use; whether indigenous peoples are participating in the development of legislation; whether health warnings are relevant to indigenous peoples, if cessation programmes are tailored for indigenous peoples; and if research, surveillance and exchange of information are relevant to indigenous peoples.

Discussion and agreement among relevant Parties regarding an appropriate indigenous reporting framework needs to occur to ensure that any additional reporting fields are relevant, practical and ultimately assist to reduce tobacco harm among indigenous peoples. To this end, an indigenous expert working group or establishment of indigenous collaborating centres for reducing commercial tobacco use could be established to help develop and review potential options for such a framework and relevant indicators.

The second mechanism for improving FCTC reporting could include Parties ensuring indigenous peoples are encouraged, engaged and supported, incorporating financial support to take domestic and international collaborative action. It is expected that this action would help improve and set standards for what is reported (eg, ethical ways of engaging with indigenous peoples). Furthermore, collaborative action could help establish consistent use (or recognise where differences are important) for terms and measures (eg, common and appropriate definitions for ethnicity and specific indigenous indicators, prompts and data collection methods) that will ultimately lead to better reporting. This action could be realised through relevant parties including indigenous-related data in their country reports, as well as advocating to the WHO to update the reporting templates and promoting to member countries why these updates are central to reducing indigenous commercial tobacco use. In the case of improving the extent of indigenous tobacco prevalence data, many countries collect high-quality data for these groups (eg, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Social Surveys in Australia, and the New Zealand Health Survey). In addition, these countries could also identify opportunities for improving their monitoring, surveillance and intervention evaluation systems that would help reporting. This would include wise practices for engaging indigenous peoples around research, recognition of achievements and innovative approaches, surveillance and evaluation and whether data are comparable, or how comparable data could be produced.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study were that indigenous peoples from Oceania and North America led and participated in all stages of the study process. This included formulating study aims, methods, analysis and interpreting results. As such, this research reflects a uniquely indigenous perspective on the quality of reporting. However, the authors recognise that perspectives from indigenous peoples outside of the scope of this project may not have been covered (such as South America or other parts of the Pacific). Further studies should be undertaken that include a broader range of countries with indigenous populations and directly engage indigenous peoples.

The study focused on what was reported in the global and country specific reports. Therefore, care should be taken when considering the findings, as the reports may not accurately reflect what is actually happening under the FCTC or in the respective countries.

Conclusion

Recognition of commercial tobacco harms and the need to partner with indigenous peoples to take action as part of FCTC commitments are essential steps towards improving indigenous health and reducing health inequities. As a result, FCTC Parties that have indigenous populations should incorporate comprehensive and high-quality standardised indigenous-specific data in their regular reporting to assist in reducing tobacco harms among indigenous peoples. Such improvement in reporting would align with the intent of the FCTC, including assisting to reaffirm the right of all people to the highest standard of health.2 12 Within the FCTC reports, we found significant gaps in what was being reported and, in many instances, it was difficult to determine if or what, if any, progress was being made under the FCTC. However, we identified some evidence that progress was being made towards reducing tobacco-related harm among indigenous peoples. This included the implementation of indigenous-focused initiatives and evidence of declining tobacco prevalence. Strengthening reporting instruments to include indigenous data is essential to realising the Guiding Principles and to close the gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous commercial tobacco use, increasing Parties’ accountability, particularly to indigenous peoples and through their obligations as WHO Members via increased reporting and transparency. This would align indigenous reporting with other specific populations identified within the FCTC reporting instruments, such as women, youth and children.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada and New Zealand have disproportionately high rates of commercial tobacco use compared with their non-indigenous counterparts.

Australia, Canada and New Zealand are States Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and are thus committed to addressing the particular needs and challenges experienced by indigenous peoples in reducing commercial tobacco use. The FCTC highlights the importance of facilitating indigenous leadership and participation in developing, implementing and evaluating socially and culturally appropriate commercial tobacco reduction interventions.

Systematic reviews suggest evidence of a growing prioritisation and readiness to address the high rates of commercial tobacco use within Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Supporting such actions, and measuring progress, requires improvements in the FCTC reporting systems on actions to reduce indigenous commercial tobacco use.

What important gaps in knowledge exist on this topic

There are gaps in reporting and sharing knowledge about commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples and how commercial tobacco use can be reduced. Addressing these gaps in reporting and sharing knowledge about commercial tobacco use will help inform the reduction of smoking disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.

There is limited evidence in relation to the extent of reporting and sharing knowledge about commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples via FCTC reporting mechanisms.

What this paper adds

Existing gaps in FCTC reporting make it difficult to determine if or what progress has been made within States Parties and comparably across countries. This review points to the need for more detailed and standardised reporting on FCTC progress in achieving FCTC commitments to reducing commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples.

Strengthening FCTC reporting instruments to include indigenous-specific data will help to realise the FCTC Guiding Principles, building the evidence base and momentum to improve tobacco control and reduce commercial tobacco use among indigenous peoples.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; assisted in drafting the work and/or revising it critically for important intellectual content; made final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This research is funded in part by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (Grant Number R01-CA091021) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant Number 379337). The funders played no role in the decision to submit the article or in its preparation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Lovett R, Thurber KA, Maddox R. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking epidemic: what stage are we at, and what does it mean? Public Health Res Pract 2017;27 10.17061/phrp2741733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services, 2003:44. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carson KV. Smoking cessation and tobacco abuse prevention in Indigenous populations. Evidence Base, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minichiello A, Lefkowitz AR, Firestone M, et al. Effective strategies to reduce commercial tobacco use in Indigenous communities globally: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1 10.1186/s12889-015-2645-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Reporting on the implementation of the Convention 2017. 2017http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/en/.

- 6. Stephens C, Porter J, Nettleton C, et al. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Lancet 2007;370:1–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61742-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008:41. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jahan S. Human development report 2016: human development for everyone. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N, et al. The tobacco atlas. In: Daniel JM. ed, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Health. Annual Data Explorer 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey [Data File], 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gionet L, Roshanafshar S. Select health indicators of First Nations people living off reserve. Métis and Inuit: Statistics Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smylie J, Anderson M. Understanding the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: key methodological and conceptual challenges. CMAJ 2006;175:602 10.1503/cmaj.060940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smylie J, Firestone M. Back to the basics: Identifying and addressing underlying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for indigenous populations in Canada. Stat J IAOS 2015;31:67–87. 10.3233/SJI-150864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waa AM. Understanding parental influences on smoking uptake among Māori children: a mixed methods investigation: University of Otago, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas DP, Davey ME, Briggs VL, et al. Talking about the smokes: summary and key findings. Med J Aust 2015;202:S3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blakely T, Fawcett J, Hunt D, et al. What is the contribution of smoking and socioeconomic position to ethnic inequalities in mortality in New Zealand? Lancet 2006;368:44–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68813-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ministry of Health, University of Otago. Decades of Disparity III: Ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, New Zealand 1981–1999. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:173–88. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chamberlain C, Perlen S, Brennan S, et al. Evidence for a comprehensive approach to Aboriginal tobacco control to maintain the decline in smoking: an overview of reviews among Indigenous peoples. Syst Rev 2017;6:135 10.1186/s13643-017-0520-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas DP, Briggs V, Anderson IP, et al. The social determinants of being an Indigenous non-smoker. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:110–6. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. : Scollo M, Winstanley M, Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. 4th edn Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flannery D, Sisk-Franco C, Glover PN. The Conflict of Tobacco Education Among American Indians: Traditional Practice or Health Risk? Slama K, Tobacco and Health. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1995:903–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Well Living House. Emergent principles and protocols for Indigenous Health Service evaluation: summary report of a provincial “three ribbon” expert consensus panel. Toronto: Well Living House, Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Indian Act, RSC, 1985.

- 28. Departmental Executive Committee Finance Evaluation and Accountability. First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy - Implementation Evaluation Report, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29. T. C. Standing Committee on Health, 2006.