Extended Summary

Introduction:

Many parents who choose hypospadias repair for their son experience decisional conflict and regret. The utilization of a shared decision-making process may address the issue of decisional conflict and regret in hypospadias repair by engaging both parents and physicians in decision-making.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to develop a theoretical framework of the parental decision-making process about hypospadias surgery to inform the development of a decision aid.

Study Design:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with parents of children with hypospadias to explore their role as proxy-decision-makers, inquiring about their emotions/concerns, informational needs and external/internal influences. We conducted interviews until no new themes were identified, analyzing them iteratively using open, axial and selective coding. The iterative approach entails a cyclical process of conducting interviews and analyzing transcripts while the data collection process is ongoing. This allows the researcher to make adjustments to the interview guide as necessary based on preliminary data analysis in order to explore themes that emerge from early interviews with parents. We used grounded theory methods to develop an explanation of the surgical decision-making process.

Results:

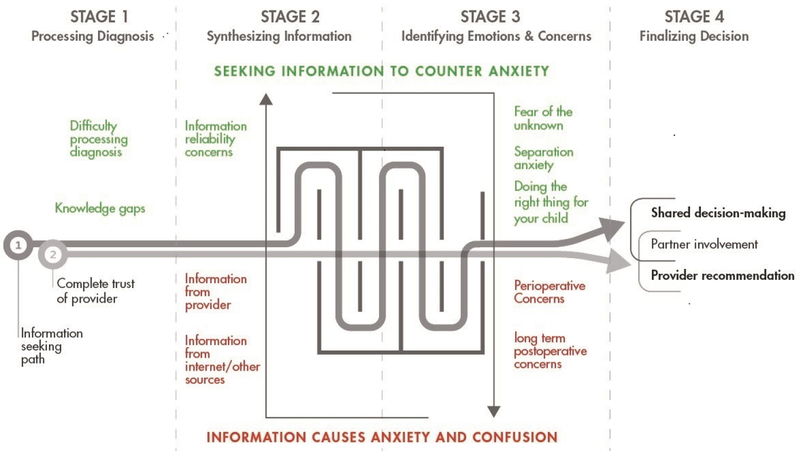

We interviewed 16 mothers and 1 father of 7 preoperative and 9 postoperative patients (n=16) with distal (8) and proximal (8) meatal locations. We identified four stages of the surgical decision-making process: 1) processing the diagnosis, 2) synthesizing information, 3) processing emotions and concerns and 4) finalizing the decision (Extended Summary Figure). We identified core concepts in each stage of the decision-making process. Primary concerns included anxiety/fear about the child not waking up from anesthesia and their inability to be present in the operating room. Parents incorporated information from the Internet, medical providers and their social network as they sought to relieve confusion and anxiety while building trust/confidence in their child’s surgeon.

Discussion:

The findings of this study contribute to our understanding of decision-making about hypospadias surgery as a complex and multi-faceted process. The overall small sample size is typical and expected for qualitative research studies. The primary limitation of the study, however, is the underrepresentation of fathers, minorities and same-sex couples.

Conclusions:

This study provides an initial framework of the parental decision-making process for hypospadias surgery that will inform the development of a decision aid. In future stages of decision aid development, we will focus on recruitment of fathers, minorities and same-sex couples in order to enrich the perspectives of our work.

Keywords: Decision making, pediatrics, hypospadias, qualitative research

Introduction

Hypospadias, an abnormal opening for urine on the bottom side of the penis, encompasses a broad spectrum of disease severity with a variable degree of long-term disability.1 Reconstructive surgery in infancy may prevent potentially serious cosmetic and functional problems into adulthood, but the decision-making process regarding hypospadias repair is challenging because it involves an irreversible choice with potentially lifelong consequences.2 Because no single management strategy can achieve all of a parent’s goals, decisional conflict (DC) may arise.3 DC may impact outcomes such as decisional regret (DR) and post-decision quality of life.3, 4

Three recent studies have identified DC and DR as a significant problem for parents who elect repair for their children.5–7 The utilization of a shared decision-making (SDM) process may address the issue of DC and DR in hypospadias repair by engaging both parents and physicians in decision-making. Shared decision-making is characterized by a bi-directional flow of information between patients and providers with an emphasis on elicitation of parental values and preferences.8 Several recent American Urological Association guidelines on complex urologic topics, in fact, suggest the necessity of shared decision-making to optimize urological care.9, 10 Engaging the parents of hypospadias patients in shared decision-making and addressing the principal components of the process is a complex task. To our knowledge, no published decision aids for pediatric urological conditions to facilitate shared decision-making exist.

The purpose of this study was to use a qualitative grounded theory approach to construct a theoretical framework that informs the process of decision-making about hypospadias surgery and contributes to the development of a hypospadias decision aid.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

We identified parents (≥ 18 years old) whose sons had documentation of hypospadias at a pediatric urology clinic appointment between October 2017 and January 2018. We contacted them via telephone to discuss study participation and obtained verbal informed consent. We included parents of postoperative patients (surgery <6 months prior) and those who were awaiting repair, excluding parents <18 years old. Each participant was compensated $20 for study participation. The study was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board (#1511846401).

Data Collection

We developed a semi-structured qualitative interview script based on a review of the hypospadias literature and consultation with seven pediatric urologists. A qualitative researcher (JP) conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with parents. Table 1 gives examples of the open-ended and directed questions we asked during the interviews. Interviews lasted approximately 30–60 minutes and explored the parents’ role as proxy-decision-makers, inquiring about their emotions/concerns, informational needs and influences regarding the decision about hypospadias surgery. We conducted additional interviews until no new themes arose from additional participants thereby reaching theoretical saturation. We audio recorded and professionally transcribed the interviews. We verified and corrected all transcription errors prior to data analysis.

Table 1:

Example Questions from Semi-structured Interviews with Parents of Pediatric Patients with Hypospadias

| Diagnosis |

| Please describe your son’s medical condition in your own words. |

| When and how you did you learn about the diagnosis? |

| How did the diagnosis make you feel? |

| Had you ever heard of this condition prior to his diagnosis? |

| Circumcision issues |

| What were your thoughts about circumcision before your son was born? |

| Were you concerned about the need for anesthesia if circumcision was done at a later time? If so, what were your concerns? |

| Information-seeking behavior |

| What did you use to get more information about your son’s condition? |

| What information been most helpful to you in understanding your son’s condition? |

| What information has been most helpful to you in making a decision about surgery? |

| Did you think your received enough information to feel comfortable with your decision? |

| Did the surgeon made the decision about surgery for you or did you make it together? |

| Is there information that you feel is missing that would help you more? |

| Initial concerns |

| What were some of your initial concerns for your son’s future regarding hypospadias? |

| What questions did you have for the urologist at the time of the clinic visit? |

| Perioperative concerns and expectations |

| How do you feel about your son’s upcoming surgery? |

| What are your least/greatest concerns about the surgery? |

| Do you have any concerns that were not addressed? |

| Is there anything you are worried about right now regarding the surgery? |

| What are your expectations about how the penis will look and function after the surgery? |

| What are your expectations about your son’s recovery after surgery? |

| Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you would like to share? |

| Additional questions for postoperative parents |

| What was the day of surgery like for you and your son? |

| Can you tell me about your feelings on that day? |

| Is there a moment that stands out as the hardest/best moment from that day? |

| What was the recovery like? Was there anything that surprised you about it? |

| What matters most to you now for your son’s future? |

| Do you have any concerns about your son’s hypospadias now that he’s had the surgery? |

| Do you have any regrets about the surgery? |

| Is there any information that would have made the decision easier for you? |

Analysis

We used NVivo qualitative research software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria Australia) to analyze the interview transcripts iteratively using grounded theory methodology. Grounded theory is a well-established qualitative research methodology that has been used in social, behavioral and clinical sciences for over four decades. Unlike top-down deductive approaches, grounded theory works from the bottom-up using observations as they emerge from systematic analysis of data, in this case interviews with parents of children undergoing hypospadias repair.12,13 It is unique in that data for analysis are based on participants’ “lived” experiences, devoid of the researcher’s preconceived ideas or notions.13 This approach is particularly useful where little is known about the phenomenon of interest, as is true in this case. Analysis using grounded theory methods entails an iterative process of reviewing interview transcripts looking for patterns or themes. We began by independently performing open coding of the interview transcripts, analyzing them line-by-line to develop provisional concepts.15 Two of the authors (KC and JP) compared and collapsed the provisional concepts into categories.16 During axial coding, we focused specifically on an emerging category and we used selective coding to identify the core concepts. We integrated the core concepts into a theoretical framework of the decision-making process for hypospadias surgery.16 In addition, we used theoretical sampling, the process of data collection directed by evolving theory, to choose participants, modify the interview guide and add data sources as the study progressed.11, 16, 17 The institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Sample

Of the 43 parents we attempted to contact via telephone, 22 were not reachable, 4 refused to participate because of a lack of interest and 2 parents were not eligible: one was a foster parent and one stated that their son did not have hypospadias. Of the 21 eligible parents whom we contacted, 17 agreed to participate in the study (81%). There were 16 mothers and 1 father who participated: 8 preoperative and 9 postoperative, 15 Caucasians and 2 African-Americans, ages 21–43, with diverse educational backgrounds and marital status (Table 2). We interviewed two parents (mother and father) of the same patient for a total of 17 parent interviews regarding 16 patients. Urethral location was distal in 8 patients and proximal in 8 patients.

Table 2:

Demographics of parent participants and their sons at the time of the interview

| No. parent participants | N=17 |

|---|---|

| Median age at interview (interquartile range) | 31 (26–34) |

| No. parenting role (%) | |

| Mother | 16 (94.1%) |

| Father | 1 (5.9%) |

| Relationship status (%) | |

| Single (never married) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Married | 10 (58.8%) |

| Divorced | 4 (23.5%) |

| No. race/ethnicity (%) | |

| Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 15 (88.2%) |

| African-American | 2 (11.8%) |

| No. education level (%) | |

| Some high school | 1 (5.8%) |

| High school graduate | 4 (23.5%) |

| Some college | 1 (5.9%) |

| Associate’s degree | 2 (11.8%) |

| Bachelor degree | 5 (29.4%) |

| Graduate degree | 4 (23.5%) |

| Timing of interview relative to surgery (%) | |

| Preoperative | 8 (47.1%) |

| Postoperative | 9 (52.9%) |

| Meatal location* | |

| Glans | 1 (5.9%) |

| Distal shaft/subcoronal | 7 (41.2%) |

| Mid shaft | 3 (17.6%) |

| Penoscrotal | 5 (29.4%) |

(17 parents of 16 patients: one mother/father pair)

Theoretical framework

The Psychosocial Problem

The psychosocial problem shared by parents who make surgical decisions for their sons with hypospadias is the challenge of identifying and synthesizing high-quality information in a timely fashion about an unfamiliar condition in order to act as proxy decision-makers, leading to anxiety, stress and confusion.

The Psychosocial Process

Analysis of the participants’ narratives revealed four key stages in the decision-making process about hypospadias surgery for their sons. Figure 1 represents the framework of the decision-making process with boxes indicating the core concepts in each stage. The four stages are (a) Processing the diagnosis, (b) Synthesizing information, (c) Processing emotions and concerns and (d) Finalizing the decision. Anxiety and confusion are present throughout the decision-making process and parents revisit these stages in a cyclic fashion throughout the decision-making process. As parents synthesize information from a variety of sources they find reassurance from providers and develop trust in them. Tables 2 and 3 depict the core concepts in each phase of the decision-making process with illustrative quotes from the parent interviews.

Figure 1:

Grounded theory framework of the parental decision-making process about hypospadias surgery

Table 3:

Processing the diagnosis and Synthesizing Information

| STAGE 1 | PROCESSING THE DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Difficulty processing diagnosis |

| PRE-2 | “I had a C-section…and I heard, ‘well, it looks like he has a little bit of hypospadias”…and of course I am like ‘what’s that?’ They just said ‘don’t worry about it’ and they were trying to keep me calm. They kind of halfway explained it while I was laying on the table.” |

| POST-5 | “It’s a lot of information to get after having a baby, even six months later when you’re actually going into the surgery, there are still questions that you forget to ask and there’s so much information being thrown at you…” |

| PRE-16 | “There’s two holes on the underside of his penis…I don’t know. That part was kind of confusing for me. I thought for some reason that there was like two separate holes in the head of the penis, one for pee and one for sperm but then my boyfriend explained it differently. He’s like, ‘no, it’s one.’“ |

| POST-4 | “I also had no idea what to expect…until I did research. I didn’t know there were different degrees of the problem and then I also didn’t realize how severe our son’s case was until the first meeting.” |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Information seeking behavior (parent) |

| PRE-2 | “I started with Google and then specific sites I couldn’t tell you. There is a lot of blogs which I hate, but of course I still looked at them…parents commenting on the surgery either helps or it is too extreme. It was either great or horrible. I recognize that I don’t know. I don’t write on blogs. I kind of feel typically write their complaints more than [anything].” |

| POST-10 | “I just went online on my phone and started looking it up and reading stuff and seeing images of what it could have been. I didn’t see any picture of what my son looked like comparatively. I was glad because some of the images that they show are just horrific. I was just like, oh my gosh, this is how bad it could have been.” |

| PRE-3 | “My first [understanding] of the whole situation was the doctor actually coming in and taking off his diaper and actually showing me where the hole was and where it was supposed to be and then actually showing me a graph. It showed where the hole was supposed to be and where his was and [what] major issues other kids had…so I think that is when I actually had a pretty good idea of what it was.” |

| POST-14 | “I think Dr. X did a really good job explaining it. Because even my husband is nodding and he doesn’t have any medical background whatsoever…I feel Dr. X gave us a lot of information. I know quite a few surgeons and they aren’t all as thorough as Dr. X is.” |

PRE=preoperative, POST=postoperative

Stage 1: Processing the diagnosis

Parents described difficulty processing the diagnosis due to inadequate information, fear, self-blame, dismissive comments from providers and information overload (Table 2). The chaotic environment in the delivery room as well as medication side effects and sleep deprivation contributed to difficulty processing information (Table 2). They also described knowledge gaps about the condition including the cause of hypospadias, basic penile anatomy, the spectrum of severity of hypospadias and the definition of chordee (Table 2). At the time of diagnosis, many parents found comfort in the common occurrence of the condition and the relatively mild degree of their sons’ hypospadias compared to others.

Stage 2: Synthesizing Information

Parents used a variety of sources to seek information including medical providers, websites and family and friends (Table 2). Websites included parent blogs, patient testimonials, medical journals and hospital websites. Most parents performed extensive online research about hypospadias but acknowledged their lack of knowledge about the reliability of the information. Some parents avoided online searching due to concerns about false information or the possibility of websites creating additional anxiety about the condition. Providers also used a variety of methods to educate parents including demonstrating on the baby, drawing pictures and describing the condition using layman’s terms. They also provided reassurance and support by referencing their professional and personal experience with the condition in a family member (Table 2).

Stage 3: Processing Emotions and Concerns

Parents’ primary emotions in the preoperative period were fear of the unknown and separation anxiety regarding anesthesia for their child (Table 3). Parents were significantly more concerned about anesthesia than they were about the procedure itself. They expressed specific concerns about the child not waking up from anesthesia and their inability to be present in the operating room (Table 3). Participants’ perioperative concerns were primarily related to pain control, possible developmental or behavioral changes from anesthesia and urethral catheter and wound care (Table 3). They also expressed concerns about doing the right thing for the child in order for them to have a normal life (Table 3). As parents processed emotions and concerns (Stage 3) they continued to synthesize information (Stage 2) in a cyclic fashion (Figure 1).

Stage 4: Finalizing the Decision

Parents weighed information from multiple sources including the Internet and their respective partners and providers as they finalized decisions (Table 3). Many parents stated that their provider made a recommendation to proceed with surgery but most of them felt that the final decision was up to them. Most cited the critical importance of building trust and confidence in their child’s surgeon due to provider behaviors such as reassurance, information provision and self-disclosure about their surgical experience (Table 3). Some parents described a shared decision-making process with their providers and cited the importance of their partner’s involvement in the decision (Table 3). All of participants were comfortable with their decision for surgery at the end of the process, citing the importance of confidence in the surgeon and reassurance about a positive outcome.

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to our understanding of decision-making about hypospadias surgery as a complex and multi-faceted process. Parents described a cyclic process of experiencing emotions and concerns as they sought information in order to alleviate anxiety and confusion. They built trust with their child’s surgeon in response to key provider behaviors such as self-disclosure, support and reassurance. These behaviors resulted in greater confidence in the surgeon’s abilities as they moved toward decision satisfaction.

Grounded theory is the most appropriate of several qualitative techniques for analyzing a process such as decision-making about surgery. First, the type of data, interview transcripts, lends itself to the iterative consensus process of analysis used in grounded theory; second, little is known about this area, making grounded theory ideal as an approach; and third prior studies have utilized grounded theory techniques to analyze decisions in other areas of healthcare.18,19 Since the analysis is ongoing, this approach also allows the researcher to make refinements and adjustments to the interview questions to give them greater depth and breadth, something that is not possible using pre-established deductive methods.14 Whereas qualitative methodologies are most useful for predicting outcomes. Qualitative methods are useful for discovering the meaning parents attach to their son’s diagnosis, prognosis and treatment.

Several key findings from our study will contribute to the future development of a decision aid. First, we noted that parents’ informational needs remained salient from the time of diagnosis through the postoperative period, encompassing the initial clinic visit, the day of surgery and beyond. Second, we noted knowledge gaps in specific content areas including the causes of hypospadias, the spectrum of severity, basic penile anatomy and the definition of chordee. Third, parents were significantly more concerned about anesthesia than they were about the procedure itself. Fourth, a parent’s relationship with his or her provider and the opportunity for clarification of information were critical components of the decision-making process.

Based on our findings, we see the need for a decision aid that is available online or as a smartphone application and is customizable to parents’ specific concerns and informational needs. Such an aid should include educational content to address the specific knowledge gaps noted above. The inclusion of an educational module about the risks of anesthesia could help alleviate parental fear and anxiety about anesthesia. In our view, the decision aid should also include questions about parental preferences for circumcision and the option to be present in the operating room during the induction of anesthesia. Finally, we believe it would be useful to develop a decision aid that can stand alone or be used in collaboration with the provider during the clinical visit.

One of the strengths of our study was the inclusion of parents with diverse demographic characteristics (i.e. marital status and educational background) whose sons experienced a wide spectrum of hypospadias severity. Although our sample included parents of various educational backgrounds, there was an overrepresentation of college-educated participants as compared to the state of Indiana. Census data from the state of Indiana in 2017 reported that 16.1% of state residents had a Bachelor’s degree and 9.2% had a graduate degree or more.20 In our study, 29.4% of the participants had a Bachelor’s degree and 23.5% had a graduate degree. We included pre- and postoperative parents in order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the decision-making process and surgical experience from beginning to end. We wanted to capture all phases of the decision about surgery. We thought it would be helpful to include postoperative parents who could reflect on their decision-making process and the actual experience of their son having surgery. They could also provide input on decisional regret and advise us about potential content areas for the decision aid. The overall small sample size is typical and expected for qualitative research studies. One of the limitations of the study, however, is the underrepresentation of fathers, minorities and same-sex couples. The small number of minority participants reflects the racial composition of our local area. The predominance of mothers in our study was likely related to the prominent role of mothers in our pediatric urology practice. Mothers were listed as the primary contact for all of families we approached about study participation. Although we inquired about participation by all of the male partners we were able to recruit only one of the fathers. In future studies, we plan to apply purposive sampling techniques to focus on recruitment of fathers, same-sex and minority parents. Future sampling strategies may include recruitment on the day of surgery when both partners are likely to be present and possibly home visits at a time that is convenient for both parents to be available.

Our findings are consistent with the limited literature on parental decision-making in hypospadias surgery.6, 7, 21 Keays and colleagues identified “priority domains” for a patient-reported outcomes measure for hypospadias patients based on a literature review, several focus groups and a small series of open-ended interviews with patients and caregivers.21 The domains included satisfaction with urination, appearance and erection and overall well-being.21 Although the parents in our study expressed similar concerns, they prioritized perioperative worries, particularly about the risks of general anesthesia and the recovery process for their sons. The differences we found are likely due to the timing of the interviews relative to surgery and the content of the interviewer’s questions. Lorenzo and colleagues found no evidence of discrepancy in parental decisional conflict between mothers and fathers making decisions about hypospadias surgery.7 We noted a variable level of paternal involvement in the decision with some fathers having no role and others participating jointly with the mother. In a subsequent study, Lorenzo and colleagues noted that decisional regret was significantly associated with postoperative complications, parental desire to avoid circumcision and evidence of preoperative decisional conflict.6 Keays and colleagues also noted that parents of sons who had no surgical complications were most satisfied with the appearance of the genitals.21 We did not have sufficient duration of follow up or adequate statistical power to assess the potential association of complications and decisional regret. Since the vast majority of participants’ desire circumcision for their sons, the inclusion of circumcision in the hypospadias surgery was not a concern for most parents.

Conclusions

We conclude that developing a theoretical framework, informed by interviews with parents about their hopes and concerns regarding hypospadias surgery, will provide the evidence necessary to develop a tool that addresses parental anxiety and decisional regret. It is possible that the preoperative education provided by a hypospadias decision aid could decrease parental anxiety. We plan to measure this outcome in future pilot studies of the decision aid after prototype development is complete. We believe that the findings from this study are a small step in that direction. In future studies, we will improve the care of hypospadias patients by developing an evidence-based decision aid using this theoretical framework of the parental decision-making process

Table 4:

Core Concepts & Illustrative Quotes for Stages 3 and 4: Processing Concerns & Finalizing the Decision

| STAGE 3 | PROCESSING CONCERNS |

|---|---|

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Fear of the unknown |

| PRE-8 | “As far as surgery is concerned I have normal mother concerns of putting my child under anesthesia. Even just the idea of him having to get an IV again…he’ll be looking up at mom and being upset about it.” |

| PRE-15 | “I’m nervous about how he’s going to take to the surgery and if they really have to go through and move the hole to where it’s supposed to be at, concerned about him being under.” |

| Interviewee | Core concept: Separation anxiety |

| PRE-6 | “I think at the doctor’s I was crying so I can’t exactly remember but from what I got, when we will go for the surgery they will take away my son when he is not yet unconscious. So he is awake and then…they have to take him and then give him anesthesia.” |

| POST-14 | “I think the hardest part is just being separated from him and knowing that they are doing this medical procedure with anesthesia and you don’t know what’s going on and you can’t see him or comfort him….they do a pretty good job when they take him from you but it’s nerve wracking.” |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Perioperative concerns |

| PRE-16 | “[My biggest concern] is more the recovery and whether or not it’s going to set him back developmentally like he’s just now starting to pull himself up to try to stand. I’m worried that it will set him back…like he won’t want to crawl, how won’t want to try to pull himself up.” |

| POST-1 | “I guess I wasn’t prepared for [the urethral catheter] because when my boys had the surgery they were still in diapers. I was so worried I was going to get it dirty and if they had a diaper that was bad and it was going to get an infection. That was a big concern for me….just to try and keep it clean.” |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Doing the right thing for the child |

| PRE-16 | “As a parent you have the final say. It’s your kid. It’s your decision. Like you do what you feel is best. But if you do chose to go ahead and do the surgery it’s okay. Others might not be too happy with your decision. But you know what? It’s your kid and you do what you feel is best for him.” |

| POST-10 | “His father’s biggest thing was that he doesn’t want his son to go through life self-conscious about himself especially when that’s something you’re intimate with every day. Obviously he wanted it to work correctly too. He wanted him to be able to have kids if he wanted to.” |

| STAGE 4 | FINALIZING THE DECISION |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Shared decision-making (with provider) |

| PRE-3 | “They let me decide completely. They decided not to do the circumcision just because I decided to do the surgery because they needed that skin because they didn’t want to use anybody else’s skin so his body didn’t reject it.” |

| POST-9 | “My husband always puts it perfectly. Nobody would ask a medical doctor to go in and raid a house in Iraq without training and so a lot of the decisions that people were asking us to make when I was pregnant were not decisions we felt like we could make without medical background. You can give us our choices, you don’t have to tell us what to do, but you have to give us education behind it.” |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Provider recommendation |

| PRE-12 | “I think they recommended [surgery] and [my partner] and I were just like, ‘yeah, let’s do it’ just because of how severe it is. I mean I feel like in some of [my son’s] history we’ve had to push for some of the surgeries that he has had and so this one, I feel like it was, ‘okay, we want to do this. Are you guys comfortable with that?’ And we’re like, ‘yeah it’s no problem.” |

| POST-5 | “I felt comfortable with the information that they were giving me…like their decision or their recommendation.” |

| Interviewee | Core Concept: Partner involvement |

| PRE-15 | “[My husband and I] made the decision together. We didn’t fully make the decision until I was able to call and talk to my husband about it.” |

| POST-10 | “He wasn’t there every day but he knew what was going on. He couldn’t sign off on anything for him so basically it was my decision.” |

PRE=preoperative, POST=postoperative

Funding source

K23 Career Development Award (1K23DK111987–01) from the National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baskin LS, Ebbers MB: Hypospadias: anatomy, etiology, and technique. J Pediatr Surg, 41: 463, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timing of elective surgery on the genitalia of male children with particular reference to the risks, benefits, and psychological effects of surgery and anesthesia. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics, 97: 590, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connor AM: Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making, 15: 25, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ et al. : Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making, 23: 281, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghidini F, Sekulovic S, Castagnetti M: Parental Decisional Regret after Primary Distal Hypospadias Repair: Family and Surgery Variables, and Repair Outcomes. J Urol, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenzo AJ, Pippi Salle JL, Zlateska B et al. : Decisional regret after distal hypospadias repair: single institution prospective analysis of factors associated with subsequent parental remorse or distress. J Urol, 191: 1558, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenzo AJ, Braga LH, Zlateska B et al. : Analysis of decisional conflict among parents who consent to hypospadias repair: single institution prospective study of 100 couples. J Urol, 188: 571, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med, 44: 681, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AUA Staff: AUA White Paper on Implementation of Shared decision making into urological practice American Urological Association. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL et al. : Surgical Management of Stones: American Urological Association/Endourological Society Guideline, PART I. J Urol, 196: 1153, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwandt TA: Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starks H, Trinidad SB., Chose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res, 17:1372, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghezeljeh TN, Emami A Grounded theory: methodology and philosophical perspective. Nurse Res, 17: 15, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez CA Getting grounded: using Glaserian grounded theory to conduct nursing research. Can J Nurs Res, 42: 150, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss A: Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draucker CB, Martsolf DS, Ross R et al. : Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory. Qual Health Res, 17: 1137, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charmaz K: Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Low LP, Lam LW, Fan KP Decision-making experiences of family members of older adults with moderate dementia towards community and residential care home services: a grounded theory study protocol. BMC Geriatr, 17: 120, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godino L, Jackson L, Turchetti D, Hennessy C, Skirton H Decision making and experiences of young adults undergoing presymptomatic genetic testing for familial cancer: a longitudinal grounded theory study. Eur J Hum Genet 26: 44–53, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). Census Bureau QuickFacts, United States Census Bureau, 29 Nov. 2018, www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

- 21.Keays MA, Starke N, Lee SC et al. : Patient Reported Outcomes in Preoperative and Postoperative Patients with Hypospadias. J Urol, 195: 1215, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]