Abstract

Purpose

Stepped care (SC), consisting of watchful waiting, guided self-help, problem-solving therapy, and psychotherapy/medication is, compared to care-as-usual (CAU), effective in improving psychological distress. This study presents secondary analyses on subgroups of patients who might specifically benefit from watchful waiting, guided self-help, or the entire SC program.

Methods

In this randomized controlled trial, head and neck and lung cancer patients with distress (n = 156) were randomized to SC or CAU. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate baseline factors associated with recovery after watchful waiting and guided self-help. Potential moderators of the effectiveness of SC compared to CAU were investigated using linear mixed models.

Results

Patients without a psychiatric disorder, with better psychological outcomes (HADS: all scales) and better health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (EORTC QLQ-C30/H&N35: global QOL, all functioning, and several symptom domains) were more likely to recover after watchful waiting. Patients with better scores on distress, emotional functioning, and dyspnea were more likely to recover after guided self-help. Sex, time since treatment, anxiety or depressive disorder diagnosis, symptoms of anxiety, symptoms of depression, speech problems, and feeling ill at baseline moderated the efficacy of SC compared to CAU.

Conclusions

Patients with distress but who are relatively doing well otherwise, benefit most from watchful waiting and guided self-help. The entire SC program is more effective in women, patients in the first year after treatment, patients with a higher level of distress or anxiety or depressive disorder, patients who are feeling ill, and patients with less speech problems.

Trial

NTR1868.

Keywords: Moderators, Psychosocial intervention, Head and neck cancer, Anxiety, Depression, Distress

Background

In the last decades, a wide range of psychosocial interventions has been developed targeting symptoms of psychological distress (i.e., anxiety and depression) in cancer patients [1–6]. These interventions differ in format (e.g., individualized or group intervention), type (e.g., self˗help or face-to-face), intensity, and duration. Stepped care (SC) models have been introduced as a method to organize psychosocial care. In SC models, patients are treated with low-intensive evidence-based interventions first, followed by more intensive interventions if symptoms do not resolve [2–5, 7]. It has been hypothesized that SC has the potential to improve the accessibility and efficacy of psychosocial care while limiting the burden on scarce healthcare resources [8].

So far, four studies have been performed on the efficacy of psychosocial SC interventions in cancer populations, including breast cancer [3], hematological cancer [5], head and neck cancer (HNC), lung cancer (LC) [4], and mixed cancer patient groups [2]. These interventions differed in care offered per step and study population targeted (i.e., all patients or patients with psychological distress only). These studies showed variable results [2–5]. The study targeting HNC and LC patients with psychological distress was found to be both effective and cost-effective [4, 9]. This study consisted of four steps, namely watchful waiting (step 1), guided self-help (step 2), face-to-face problem-solving therapy (step 3), and intensive psychological interventions and/or psychotropic medication (step 4) [10]. After step 1, 28% of all patients randomized to the SC group spontaneously recovered [4]. After step 2, approximately a third of all patients recovered [4], while after steps 3 and 4, although the sample size left was small, respectively 9 and 17% recovered. This resulted in an overall recovery rate of 55% in the SC group, while in the control group, in which care-as-usual (CAU) was provided, 29% recovered. In order to improve the efficacy of this SC program, more insight is needed into which patients specifically may benefit from steps 1 and 2 of the SC program, and which patients may not. This information is relevant to further tailor the SC program, for example by letting a patient skip a step in case this step is expected to be insufficiently effective.

Also, a detailed understanding is needed into (groups of) patients who specifically benefit from the SC program as a whole, compared to CAU. Previous studies on moderators of psychosocial care in cancer patients, in general, have consistently shown that patients with high levels of psychological distress specifically benefit from psychosocial care [6, 11, 12]. In addition, a previous individual patient data meta-analysis targeting cancer patients showed that psychosocial interventions were consistently more effective in younger patients and in those interventions in which psychotherapy was provided (compared to, e.g., psycho-education or coping skills training) [6]. For other potential moderators, so far, less consistent or only preliminary findings have been reported. A systematic review of 20 studies in cancer patients, in general, reported that patients with poorer quality of life, poorer interpersonal relationship, or lower self-efficacy specifically benefit from psychosocial interventions [13]. Also, patients with certain personality traits, such as low levels of optimism and lower levels of neuroticism, showed more beneficial results [13]. A study among HNC patients showed that a nurse-led psychosocial intervention was especially beneficial for patients who were married or living together, who had a poorer global quality of life, lower emotional functioning, or lower social functioning [14]. The SC program targeting HNC and LC patients was most beneficial for patients with a depressive or anxiety disorder, while for patients with symptoms of distress (but no depressive or anxiety disorder) the SC program was as effective as CAU [4]. More insight into other potential moderators, including sociodemographic, clinical, and quality of life factors, is warranted.

This study aimed to investigate for which (groups of) HNC and LC patients the SC program targeting psychological distress may be particularly effective. This insight was provided by (1) investigating baseline factors associated with recovery after step 1 (watchful waiting) and step 2 (guided self-help), and by (2) investigating potential moderators, including sociodemographic, clinical, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) factors, of the efficacy of SC on psychological distress compared to CAU. The results of this study are relevant to further tailor care to the individual patient.

Methods

Study population

In this study, secondary analyses were performed using data of the randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of SC among HNC and LC patients [10]. Detailed information on the eligibility criteria, selection and randomization procedure, and sample size calculation is provided in the protocol and efficacy paper [4, 10]. In short, HNC and LC patients were asked to participate in the randomized controlled trial in case they were treated with curative intent at least 1 month earlier and had increased levels of symptoms of distress, anxiety, or depression, as defined by a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) total score of > 14 or HADS-anxiety or HADS-depression subscale score of > 7. After providing informed consent and completing the first questionnaire, patients were randomized into either the SC or CAU group (1:1) by an independent person.

Medical ethical approval for this study was provided by the Medical Ethics Committee of VU University Medical Center. The study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR1868).

Stepped care and care-as-usual

The SC program consisted of four steps, namely watchful waiting (step 1), guided self-help via a book or the Internet (step 2), face-to-face problem solving therapy by a nurse (step 3), and intensive psychological interventions provided by a psychologist or psychiatrist and/or psychotropic medication (step 4) [10]. Patients stepped up to the next step if symptoms of psychological distress, anxiety, and/or depression did not resolve (i.e., HADS-total remained > 14 or HADS-depression or HADS-anxiety remained > 7). More information on the SC program is provided in the protocol paper [10]. The control group received CAU, which in most cases entailed no psychosocial care [4].

Study measures

All patients were asked to complete a set of patient-reported outcome measures at six time points during the study period, namely at T0 baseline (before randomization), immediately after the intervention period or the control period of 4 months (T1), and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after T1 (T2 to T5). The primary outcome of the study was the HADS [15, 16]. The HADS is a 14-item patient-reported outcome measure on symptoms of psychological distress, anxiety, and depression. The HADS total score ranges from 0 to 42, and the subscales from 0 to 21. A HADS total score > 14 or HADS subscale score > 7 was used as a cut-off for identifying persons with symptoms of psychological distress, anxiety or depression [17].

In conjunction with the HADS several other patient-reported outcome measures were collected, namely the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30-questions (QLQ-C30) [18, 19], the EORTC HNC-specific quality of life module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) [20], the EORTC LC-specific quality of life module (QLQ-LC13) [21], and a patient-reported outcome measure for measuring patient satisfaction with care (EORTC IN-PATSAT32) [22]. For the analyses in the present study, only the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-H&N35 domains were used. All scores were linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 score. For functioning scales and the global quality of life scale, a higher score indicates better functioning or a better quality of life, while for all symptom scales, a higher score indicated worse symptoms.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were also collected. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, marital status, and work situation, which were collected via patient self-report. Clinical characteristics included tumor location, tumor stage, treatment, and time since treatment, which were collected from the hospital information system. Finally, a diagnostic telephone interview on psychiatric diagnoses, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), was assessed before randomization [23].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated for all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

To provide insight into factors associated with recovery from psychological distress after respectively step 1 (watchful waiting) and step 2 (guided self-help), exploratory univariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Only patients randomized to the SC program were included in these analyses. Factors which were investigated encompassed all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and all baseline EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 domains, and HADS outcomes. Factors associated with recovery after step 3 (problem-solving therapy) and step 4 (intensive psychological intervention or medication) were not performed due to the small sample size left in each of the groups. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To investigate potential moderators of the efficacy of SC compared to CAU on psychological distress (HADS-total) from baseline to 12 months follow-up, exploratory linear mixed model analyses were performed including fixed effects for time, group (SC or CAU), their two-way interaction, the potential moderator, and its two- and three-way interaction with group and time and a random intercept for subject. A significant (p < 0.05) three-way interaction was considered to indicate a difference of the efficacy of SC compared to CAU between groups with different scores on the investigated moderator. Post hoc linear mixed model analyses were performed to investigate the efficacy of SC on psychological distress compared to CAU, stratified for each subgroup of the found moderators separately. These stratified models included fixed effects for time, group and their two-way interaction, and a random intercept for subject. Potential moderators included all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, having an anxiety or depressive disorder, and all baseline EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 domains, and HADS outcomes. All EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 domains, and HADS outcomes were dichotomized based on previously found cut-off scores [24, 25] or mean values found in the general population [26].

Results

Study population

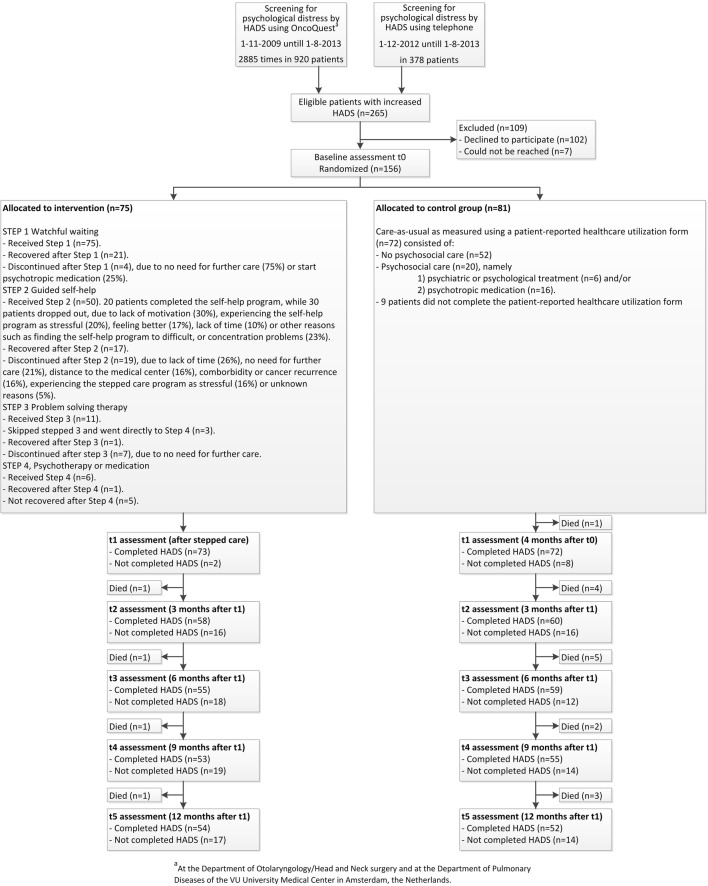

In total, 81 patients were randomized to the CAU group and 75 patients to the SC group (Fig. 1). Patients randomized to SC were more likely to be alcohol dependent than patients in the CAU group (13 versus 4%, p = 0.030), as presented in Table 1. Also, patients in the intervention group scored better on depression (8.2 versus 9.5, p = 0.029), social functioning (70.3 versus 60.3, p = 0.026), and sexuality (39.6 versus 51.7, p = 0.040) at baseline.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the care-as-usual and stepped care group

| Characteristics | Care-as-usual | Stepped care |

|---|---|---|

| N = 81 | N = 75 | |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 61.6 (10.0) | 62.5 (8.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 48 (59%) | 47 (63%) |

| Women | 33 (41%) | 28 (37%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 52 (64%) | 54 (72%) |

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 29 (36%) | 21 (28%) |

| Work situation | ||

| Paid job | 25 (31%) | 23 (31%) |

| No paid job/retired | 56 (69%) | 52 (69%) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Lip/oral cavity/oropharynx | 46 (57%) | 30 (40%) |

| Hypopharynx/larynx | 19 (23%) | 21 (28%) |

| Other head and neck cancers or lung | 16 (20%) | 24 (32%) |

| Tumor stage | ||

| I–II | 32 (41%) | 32 (48%) |

| III–IV | 47 (59%) | 35 (52%) |

| Unknown | 2 | 8 |

| Treatment | ||

| Single treatment | 37 (46%) | 39 (52%) |

| Combination treatment | 44 (54%) | 36 (48%) |

| Time since treatment | ||

| <= 12 months | 43 (53%) | 39 (52%) |

| > 12 months | 38 (47%) | 36 (48%) |

| CIDI diagnosis (all) | ||

| Yes | 33 (41%) | 27 (36%) |

| No | 48 (59%) | 48 (64%) |

| Anxiety or depressive disorder | ||

| Yes | 21 (26%) | 14 (19%) |

| No | 60 (74%) | 61 (81%) |

| Nicotine dependence | ||

| Yes | 15 (19%) | 12 (16%) |

| No | 66 (81%) | 63 (84%) |

| Alcohol dependence | ||

| Yes | 3 (4%) | 10 (13%)* |

| No | 78 (96%) | 65 (87%) |

*p < 0.05

Watchful waiting (step 1) and guided self-help (step 2) of the stepped care program

Of all 75 patients randomized to SC, 21 patients (28%) recovered after the first step (watchful waiting). Of the remaining 54 patients, 50 patients continued with step 2 (guided self-help). Three patients discontinued after step 1 because they reported no need for further care and one patient discontinued because he/she started psychotropic medication. Of the 50 patients, 17 patients recovered (34%), and one patient was lost to follow-up.

Table 2 presents the results of factors associated with recovery after step 1 and step 2. Patients without a psychiatric diagnosis (all diagnoses) were more likely to recover after step 1 than patients with a psychiatric diagnosis (odds ratio (OR) = 4.80, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.26–18.24). In addition, patients with higher (better) baseline scores on global quality of life and all functioning domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 were more likely to recover after step 1, compared to patients with lower (worse) baseline scores (OR ranged from 1.02–1.05 per point increase). Patients with more problems regarding fatigue, pain, insomnia, swallowing, sticky saliva, and feeling ill (OR ranged from 0.96–0.98 per point increase), and worse scores on anxiety, depression, and distress (OR ranged 0.75–0.85 per point increase) were less likely to recover after step 1. Patients with better scores on emotional functioning (OR = 1.03 per point increase, 95%CI 1.002–1.06), dyspnea (OR = 0.97 per point increase, 95%CI 0.95–0.997), and distress (OR = 0.82 per point increase, 95%CI 0.69–0.98) were more likely to recover after step 2.

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression analyses of factors associated with recovery after watchful waiting (step 1) and guided self-help (step 2)

| Characteristics | Treatment steps of the stepped care interventiona | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 Watchful waiting | Step 2 Guided self-help | |||||||

| Recovered | Not recovered | OR | 95%CI | RecoveredB | Not recoveredB | OR | 95%CI | |

| n = 21 | n = 54 | n = 17 | n = 32 | |||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 61.6 (8.4) | 62.9 (8.8) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.04 | 61.8 (7.3) | 62.8 (9.9) | 0.99 | 0.92–1.06 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 13 (28%) | 34 (72%) | 1.00 | 11 (37%) | 19 (63%) | 1.00 | ||

| Women | 8 (29%) | 20 (71%) | 1.05 | 0.37–2.96 | 6 (32%) | 13 (68%) | 0.80 | 0.24–2.70 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/living with partner | 15 (28%) | 39 (72%) | 1.00 | 12 (35%) | 22 (65%) | 1.00 | ||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 6 (29%) | 15 (71%) | 1.04 | 0.34–3.18 | 5 (33%) | 10 (67%) | 0.92 | 0.25–3.31 |

| Work situation | ||||||||

| Paid job | 7 (30%) | 16 (70%) | 1.00 | 5 (33%) | 10 (67%) | 1.00 | ||

| No paid job/retired | 14 (27%) | 38 (73%) | 0.84 | 0.29–2.48 | 12 (35%) | 22 (65%) | 1.09 | 0.30–3.94 |

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Lip/oral cavity/oropharynx | 8 (27%) | 22 (73%) | 1.00 | 6 (32%) | 13 (68%) | 1.00 | ||

| Hypopharynx/larynx | 9 (43%) | 12 (57%) | 2.06 | 0.63–6.74 | 5 (45%) | 6 (55%) | 1.81 | 0.39–8.35 |

| Other head and neck cancers or lung | 4 (17%) | 20 (83%) | 0.55 | 0.14–2.11 | 6 (32%) | 13 (68%) | 1.00 | 0.26–3.93 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||||

| I–II | 8 (25%) | 24 (75%) | 1.00 | 7 (35%) | 13 (65%) | 1.00 | ||

| III–IV | 12 (34%) | 23 (66%) | 1.57 | 0.54–4.53 | 9 (41%) | 13 (59%) | 1.29 | 0.37–4.50 |

| Unknown | 1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Treatment | ||||||||

| Single treatment | 8 (21%) | 31 (79%) | 1.00 | 9 (35%) | 17 (65%) | 1.00 | ||

| Combination treatment | 13 (36%) | 23 (64%) | 2.19 | 0.78–6.15 | 8 (35%) | 15 (65%) | 1.01 | 0.31–3.27 |

| Time since treatment | ||||||||

| <= 12 months | 11 (28%) | 28 (72%) | 1.00 | 9 (35%) | 17 (65%) | 1.00 | ||

| > 12 months | 10 (28%) | 26 (72%) | 0.98 | 0.36–2.69 | 8 (35%) | 15 (65%) | 1.01 | 0.31–3.27 |

| CIDI diagnosis (all) | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (11%) | 24 (89%) | 1.00 | 7 (33%) | 14 (67%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 18 (38%) | 30 (63%) | 4.80 | 1.26–18.24* | 10 (36%) | 18 (64%) | 1.11 | 0.34–3.66 |

| Anxiety or depressive disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (7%) | 13 (93%) | 1.00 | 5 (42%) | 7 (58%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 20 (33%) | 41 (67%) | 6.34 | 0.77–51.94 | 12 (32%) | 25 (68%) | 0.67 | 0.18–2.56 |

| Nicotine dependence | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (8%) | 11 (92%) | 1.00 | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 20 (32%) | 43 (68%) | 5.12 | 0.62–42.40 | 14 (36%) | 25 (64%) | 1.31 | 0.29–5.87 |

| Alcohol dependence | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) | 1.00 | 2 (25%) | 6 (75%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 20 (31%) | 45 (69%) | 4.00 | 0.47–33.73 | 15 (37%) | 26 (63%) | 1.73 | 0.31–9.68 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | OR | 95%CI | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | OR | 95%CI |

| Global quality of life | 71.0 (17.8) | 54.6 (19.2) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08* | 55.4 (16.1) | 52.4 (20.7) | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 |

| Physical functioning | 81.0 (19.0) | 68.4 (21.0) | 1.03 | 1.004–1.07* | 69.8 (20.7) | 67.7 (20.2) | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 |

| Role functioning | 73.8 (26.1) | 59.1 (27.3) | 1.02 | 1.001–1.04* | 62.7 (29.8) | 55.9 (25.3) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Emotional functioning | 70.2 (24.7) | 52.6 (24.7) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06* | 62.3 (23.6) | 46.0 (23.9) | 1.03 | 1.002–1.06* |

| Cognitive functioning | 83.3 (21.7) | 66.7 (27.3) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06* | 73.5 (24.3) | 60.8 (28.7) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 |

| Social functioning | 81.0 (19.2) | 66.0 (27.7) | 1.03 | 1.002–1.05* | 69.6 (25.2) | 62.9 (29.1) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Fatigue | 35.4 (25.2) | 54.5 (24.9) | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99* | 51.0 (26.9) | 58.8 (23.7) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 |

| Nausea Vomiting | 4.8 (9.3) | 12.3 (18.2) | 0.96 | 0.91–1.01 | 6.9 (11.9) | 15.1 (20.3) | 0.96 | 0.92–1.01 |

| Pain | 20.6 (26.3) | 38.4 (30.4) | 0.98 | 0.96–0.997* | 36.3 (25.8) | 43.0 (33.5) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Dyspnea | 25.4 (29.6) | 32.7 (30.6) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 19.6 (23.7) | 41.1 (32.4) | 0.97 | 0.95–0.997* |

| Insomnia | 28.6 (30.3) | 49.1 (37.9) | 0.98 | 0.97–0.999* | 35.3 (38.1) | 58.1 (37.5) | 0.98 | 0.97–1.000 |

| Loss of appetite | 17.5 (29.1) | 33.3 (35.8) | 0.98 | 0.97–1.002 | 21.6 (31.0) | 42.0 (38.5) | 0.98 | 0.97–1.002 |

| Constipation | 12.7 (22.3) | 17.9 (26.0) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 19.6 (29.0) | 18.9 (25.8) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 |

| Diarrhea | 4.8 (12.0) | 18.2 (30.4) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.003 | 23.5 (36.8) | 18.3 (28.3) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 |

| Financial problems | 20.1 (28.7) | 15.9 (25.0) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 19.6 (26.5) | 22.6 (31.5) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 |

| EORTC QLQ-H&N35c | ||||||||

| Oral pain | 20.0 (18.6) | 33.0 (29.7) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.003 | 25.5 (28.2) | 39.2 (31.8) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 |

| Swallowing | 11.7 (13.1) | 34.4 (29.2) | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99* | 29.4 (28.0) | 36.7 (29.9) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Senses problems | 27.5 (31.7) | 26.2 (25.2) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 25.5 (25.8) | 29.6 (25.9) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 |

| Speech problems | 17.8 (18.5) | 28.8 (26.2) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.004 | 23.5 (22.9) | 30.9 (27.8) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 |

| Trouble with social eating | 20.0 (26.8) | 32.7 (28.0) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.003 | 25.5 (25.1) | 37.0 (28.7) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 |

| Trouble with social contact | 11.3 (15.3) | 19.6 (19.2) | 0.97 | 0.94–1.01 | 14.5 (17.7) | 21.5 (18.3) | 0.98 | 0.94–1.01 |

| Sexuality | 34.2 (39.9) | 41.8 (32.2) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 47.1 (32.9) | 36.7 (30.4) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Teeth | 21.7 (29.2) | 22.2 (31.8) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 7.8 (18.7) | 25.6 (35.7) | 0.98 | 0.95–1.003 |

| Opening mouth | 18.3 (27.5) | 36.8 (37.2) | 0.98 | 0.97–1.000 | 31.4 (41.6) | 40.7 (36.2) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 |

| Dry mouth | 43.3 (37.6) | 55.6 (34.6) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 47.1 (33.5) | 64.1 (35.2) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.004 |

| Sticky saliva | 25.0 (26.2) | 46.3 (33.9) | 0.98 | 0.96–0.996* | 33.3 (26.4) | 51.9 (35.0) | 0.98 | 0.96–1.002 |

| Coughing | 30.0 (28.4) | 36.7 (29.8) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 29.4 (28.6) | 39.5 (30.7) | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Felt ill | 13.3 (19.9) | 35.4 (28.4) | 0.97 | 0.94–0.99* | 29.4 (26.0) | 40.7 (29.7) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 |

| HADS | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 7.3 (4.1) | 10.1 (3.0) | 0.76 | 0.64–0.92* | 9.1 (2.7) | 10.7 (3.1) | 0.82 | 0.65–1.02 |

| Depression | 6.8 (3.9) | 8.7 (3.5) | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99* | 7.7 (3.0) | 9.3 (3.4) | 0.85 | 0.70–1.04 |

| Total | 14.0 (4.1) | 18.9 (4.9) | 0.75 | 0.63–0.89* | 16.8 (3.6) | 20.0 (4.7) | 0.82 | 0.69–0.98* |

aOnly factors associated with recovery after steps 1 and 2 are presented, as the total sample size in steps 3 and 4 was too small

BThis analysis includes patients who did not recover after step 1 and who continued with step 2. Of the 54 patient who did not recover after step 1, 50 patients continued with step 2. One of these patients was lost to follow-up

cHNC patients only

*p < 0.05

Moderators of the efficacy of stepped care on psychological distress compared to care-as-usual

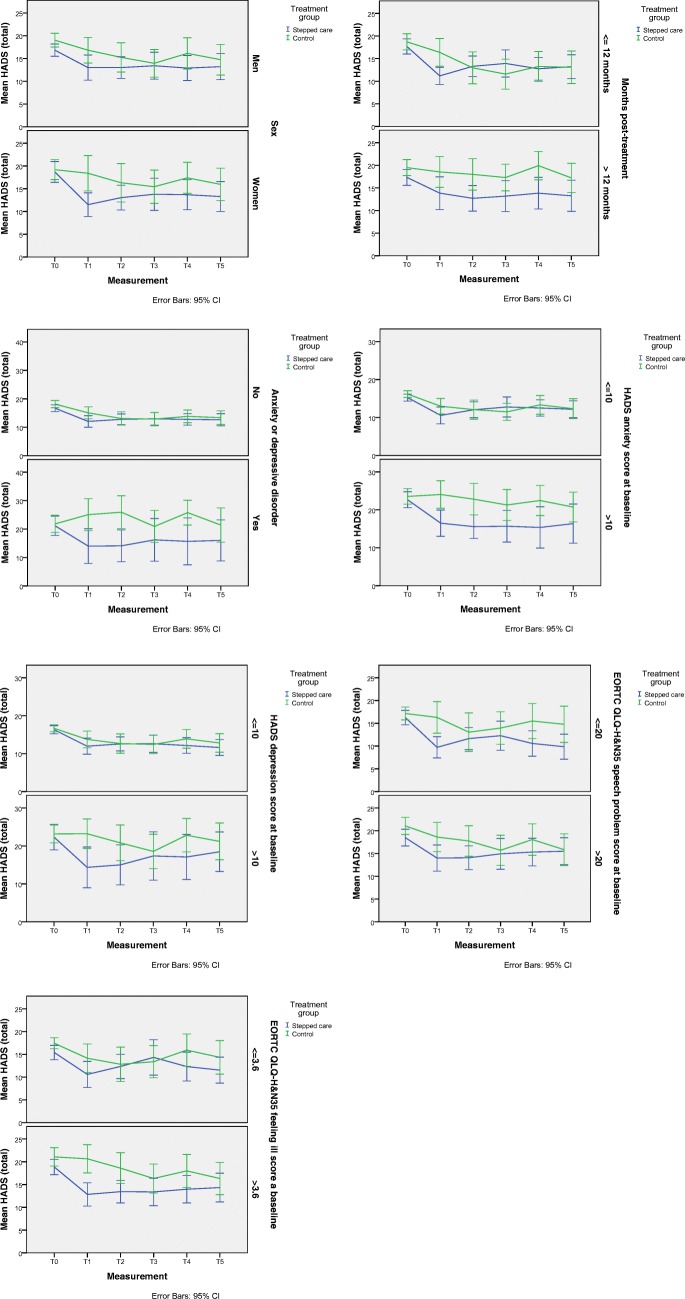

Seven factors were found to significantly moderate the effect of SC on psychological distress compared to CAU (all showed a three-way interaction of p < 0.05), namely sex, time since oncological treatment, having an anxiety or depressive disorder (as also reported in our previous study [4]), symptoms of anxiety, symptoms of depression, speech problems, and feeling ill at baseline (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Post hoc analyses showed that SC was more effective in women (p = 0.002), patients in the first year after treatment (p < 0.001), patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder (p = 0.002), patients with worse score on anxiety (p = 0.002), depression (p = 0.002) and feeling ill (p < 0.001), and patients with better scores on speech problems (p < 0.001) at baseline, compared to CAU. In men (p = 0.14), patients longer than 1 year after treatment (p = 0.40), patients without an anxiety disorder (p = 0.18), patients with better scores on anxiety (p = 0.052), depression (p = 0.40) and feeling ill (p = 0.056), and worse scores on speech problems (p = 0.11), SC was as effective as CAU.

Table 3.

Significant moderators of the effect of stepped care on psychological distress compared to care-as-usual

| Moderator | Condition | N | Moderation analyses | Post hoc analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (df)1 three-way interaction |

P value three-way interaction |

F (df)1 two-way interaction |

P value two-way interaction |

||||

| Sex | Men | Stepped care | 47 | 2.328 (578.99) | 0.041 | 1.684 (342.75) | 0.14 |

| Care-as-usual | 48 | ||||||

| Women | Stepped care | 28 | 3.985 (236.51) | 0.002 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 33 | ||||||

|

Months since treatment |

<= 12 months | Stepped care | 39 | 2.869 (578.93) | 0.014 | 5.288 (293.17) | < 0.001 |

| Care-as-usual | 43 | ||||||

| > 12 months | Stepped care | 36 | 1.036 (285.54) | 0.40 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 38 | ||||||

| Anxiety or depression disorder | No | Stepped care | 61 | 4.018 (580.63) | 0.001 | 1.517 (467.32) | 0.18 |

| Care-as-usual | 60 | ||||||

| Yes | Stepped care | 14 | 4.058 (111.96) | 0.002 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 21 | ||||||

| HADS-anxiety | <= 10 | Stepped care | 52 | 3.093 (584.39) | 0.009 | 2.219 (401.71) | 0.052 |

| Care-as-usual | 49 | ||||||

| > 10 | Stepped care | 23 | 4.014 (181.44) | 0.002 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 32 | ||||||

| HADS-depression | <= 10 | Stepped care | 60 | 2.397 (580.67) | 0.036 | 1.035 (426.21) | 0.40 |

| Care-as-usual | 51 | ||||||

| > 10 | Stepped care | 15 | 3.880 (155.23) | 0.002 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 30 | ||||||

| EORTC QLQ-H&N35 speech problems | <= 20 | Stepped care | 32 | 2.619 (536.07) | 0.024 | 4.966 (232.99) | < 0.001 |

| Care-as-usual | 32 | ||||||

| > 20 | Stepped care | 37 | 1.805 (303.33) | 0.11 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 43 | ||||||

| EORTC QLQ-H&N35 feeling ill | <= 3.6 | Stepped care | 28 | 2.392 (540.92) | 0.037 | 2.186 (241.42) | 0.056 |

| Care-as-usual | 35 | ||||||

| > 3.6 | Stepped care | 41 | 4.590 (299.78) | < 0.001 | |||

| Care-as-usual | 41 |

N, number of patients; df, degrees of freedom; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; EORTC QLQ-H&N35, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer head and neck cancer-specific quality of life module

1Numerator df = 5

Fig. 2.

Moderators (HADS total)

Discussion

This study aimed to provide insight into groups of HNC and LC patients for which the SC program, consisting of watchful waiting, guided self-help, face-to-face problem-solving therapy, and intensive psychological interventions and/or psychotropic medication, as steps with increasing intensity of treatment, may be particularly effective. It was found that patients with less impairments in functioning and symptoms at baseline benefitted from watchful waiting and guided self-help. Also, patients without a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to recover after 2 weeks of watchful waiting, compared to patients with a psychiatric diagnosis. In addition, it was found that the SC program as a whole, compared to CAU, was especially effective in women, patients in the first year after treatment, patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder, patients with a worse baseline score on anxiety, depression and feeling ill, and patients with a better score on speech problems.

Especially patients with psychological distress but who are doing relatively well otherwise (without a psychiatric diagnosis and with less impairment in functioning and less symptoms) seem to benefit from watchful waiting as such. This may be explained by the fact that patients are screened on psychological distress at their follow-up visit. Reassurance after this visit that the cancer is in remission may have resulted in the diminishment of psychological distress [4]. It makes sense that patients who spontaneously recover are the patients with less impairments in functioning or symptoms. Of those patients who did not spontaneously recover, 34% recovered after guided self-help. Also, patients who benefitted from this step were doing relatively well (better scores on emotional functioning, dyspnea, and psychological distress). The findings on emotional functioning and psychological distress are consistent with the tenets of SC in which low-intensive treatment is expected to be beneficial in patients with lower level of symptoms, while more intensive treatments are saved for those patients with more serious symptoms.

When focusing on the SC program as a whole, we found that SC was, compared to CAU, especially beneficial in women, patients in the first year after treatment, patients who were doing relatively not so well, and patients with better scores on speech problems. The finding that the SC program was particularly effective in patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder or patients with worse anxiety and depression symptoms is in line with previous studies [6, 11, 12]. Our result that SC is especially effective in women is, however, in contrast to the results of a meta-analysis using individual patient data of mixed groups of cancer patients [6] and a nurse-led psychosocial intervention in patients with HNC, which found no moderating effect of sex [14]. Another meta-analysis among mixed groups of cancer patients, on the other hand, showed higher effects in men [27], but after excluding sex-specific cancers (e.g., breast and prostate) no statistically significant difference in effect was evident [27]. Further research is needed to investigate whether our finding that SC is especially beneficial in women can be replicated.

HRQOL outcomes, including global quality of life, emotional functioning, and social functioning, were not found to moderate the efficacy of SC in the present study, while these factors have been found to moderate the efficacy of a nurse-led psychosocial intervention among HNC patients [14]. This warrants further research on the moderating role of HRQOL on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions. The reason why patients with a better HRQOL score on speech problems may benefit more from SC may be that, especially for problem-solving therapy and intensive psychological interventions (steps 3 and 4), oral conversations are part of the psychosocial treatment. In case of speech problems, it may be difficult to express oneself, which might potentially impair the effect of such psychosocial interventions.

Study limitations

A major limitation is that this study was not powered to perform these secondary exploratory analyses, therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Because of the low sample size, we also only performed univariate logistic regression analyses and did not investigate factors associated with recovery after steps 3 and 4. Moreover, only a few patients with LC participated in this study impairing the generalizability of the findings to this group of cancer patients.

Clinical implications

This study provided important information to further tailor SC to the individual patient. Results showed that patients who benefitted from watchful waiting and guided self-help were those with less impairments in functioning and symptoms. Also, patients who recovered after 2 weeks of watchful waiting less often had a psychiatric diagnosis, compared to patients who did not recover. The SC program as a whole was especially effective in women, patients in the first year after treatment, patients with an anxiety or depressive disorder, patients with worse scores on anxiety, depression, and speech problems, and patients with better scores on feeling ill, as compared to CAU. This information can be used to further tailor SC, e.g., by skipping steps which are expected to be insufficiently effective to the individual patient in clinical practice.

Funding

This study was funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, grant number 300020012. The funding agency had no influence on interpreting the data.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Kuffner R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:782–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer S, Danker H, Roick J, Einenkel J, Briest S, Spieker H, Dietz A, Hoffmann I, Papsdorf K, Meixensberger J, Mossner J, Schiefke F, Dietel A, Wirtz H, Niederwieser D, Berg T, Kersting A (2017) Effects of stepped psychooncological care on referral to psychosocial services and emotional well-being in cancer patients: a cluster-randomized phase III trial. Psychooncology 26(10):1675–1683 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Rissanen R, Nordin K, Ahlgren J, Arving C. A stepped care stress management intervention on cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms among breast cancer patients-a randomized study in group vs. individual setting. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1028–1035. doi: 10.1002/pon.3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krebber A, Jansen F, Witte B, Cuijpers P, de Bree R, Becker-Commissaris A, van Straten A, Eeckhout A, Beekman A, Leemans C, Verdonck-de Leeuw I. Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck cancer and lung cancer patients: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braamse AM, van Meijel B, Visser OJ, Boenink AD, Cuijpers P, Eeltink CE, Hoogendoorn AW, van Marwijk Kooy M, van Oppen P, Huijgens PC, Beekman AT, Dekker J. A randomized clinical trial on the effectiveness of an intervention to treat psychological distress and improve quality of life after autologous stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2509-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalter J, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Sweegers MG, Aaronson NK, Jacobsen PB, Newton RU, Courneya KS, Aitken JF, Armes J, Arving C, Boersma LJ, Braamse AMJ, Brandberg Y, Chambers SK, Dekker J, Ell K, Ferguson RJ, Gielissen MFM, Glimelius B, Goedendorp MM, Graves KD, Heiney SP, Horne R, Hunter MS, Johansson B, Kimman ML, Knoop H, Meneses K, Northouse LL, Oldenburg HS, Prins JB, Savard J, van Beurden M, van den Berg SW, Brug J, Buffart LM (2018) Effects and moderators of psychosocial interventions on quality of life, and emotional and social function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 22 RCTs. Psychooncology 27(4):1150–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Schuurhuizen CS, Braamse AM, Beekman AT, Bomhof-Roordink H, Bosmans JE, Cuijpers P, Hoogendoorn AW, Konings IR, van der Linden MH, Neefjes EC, Verheul HM, Dekker J. Screening and treatment of psychological distress in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: study protocol of the TES trial. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:302. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1313-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Straten A, Hill J, Richards D, Cuijpers P. Stepped care treatment delivery for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:231–246. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen F, Krebber AM, Coupe VM, Cuijpers P, de Bree R, Becker-Commissaris A, Smit EF, van Straten A, Eeckhout GM, Beekman AT, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Cost-utility of stepped care targeting psychological distress in patients with head and neck or lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:314–324. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krebber AM, Leemans CR, de Bree R, van Straten A, Smit F, Smit EF, Becker A, Eeckhout GM, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Stepped care targeting psychological distress in head and neck and lung cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, Sohl S, Cannella D, Targhetta V. Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2010;33:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtmaat K, van der Spek N, Witte BI, Breitbart W, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2017) Moderators of the effects of meaning-centered group psychotherapy in cancer survivors on personal meaning, psychological well-being, and distress. Support Care Cancer 25(11):3385–3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Tamagawa R, Garland S, Vaska M, Carlson LE. Who benefits from psychosocial interventions in oncology? A systematic review of psychological moderators of treatment outcome. J Behav Med. 2012;35:658–673. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Meulen IC, May AM, de Leeuw JR, Koole R, Oosterom M, Hordijk GJ, Ros WJ. Moderators of the response to a nurse-led psychosocial intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2417–2426. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2603-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27:363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vodermaier A, Linden W, Siu C. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: a systematic review of assessment instruments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1464–1488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fayers P, Bottomley A. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(Suppl 4):S125–S133. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, de Graeff A, Boysen M, Evensen JF, Biorklund A, de Leeuw JR, Fayers PM, Jannert M, Westin T, Kaasa S. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1008–1019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Kaasa S, Sullivan M. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 1994;30a:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredart A, Bottomley A, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Coens C, D'Haese S, Chie WC, Hammerlid E, Arraras JI, Efficace F, Rodary C, Schraub S, Costantini M, Costantini A, Joly F, Sezer O, Razavi D, Mehlitz M, Bielska-Lasota M, Aaronson NK. An international prospective study of the EORTC cancer in-patient satisfaction with care measure (EORTC IN-PATSAT32) Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2005;41:2120–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO--composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen F, Snyder CF, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Identifying cutoff scores for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the head and neck cancer-specific module EORTC QLQ-H&N35 representing unmet supportive care needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1493–E1500. doi: 10.1002/hed.24266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, Becker A, Brug J, van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23:121–130. doi: 10.1002/pon.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Buffart LM, Heymans MW, Rietveld DH, Doornaert P, de Bree R, Buter J, Aaronson NK, Slotman BJ, Leemans CR, Langendijk JA. The course of health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiation: a prospective cohort study. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heron-Speirs HA, Baken DM, Harvey ST. Moderators of psycho-oncology therapy effectiveness: meta-analysis of socio-demographic and MedicalPatient characteristics. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2012;19:402–416. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]