Abstract

The role of trees in the nitrous oxide (N2O) balance of boreal forests has been neglected despite evidence suggesting their substantial contribution. We measured seasonal changes in N2O fluxes from soil and stems of boreal trees in Finland, showing clear seasonality in stem N2O flux following tree physiological activity, particularly processes of CO2 uptake and release. Stem N2O emissions peak during the vegetation season, decrease rapidly in October, and remain low but significant to the annual totals during winter dormancy. Trees growing on dry soils even turn to consumption of N2O from the atmosphere during dormancy, thereby reducing their overall N2O emissions. At an annual scale, pine, spruce and birch are net N2O sources, with spruce being the strongest emitter. Boreal trees thus markedly contribute to the seasonal dynamics of ecosystem N2O exchange, and their species-specific contribution should be included into forest emission inventories.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Biogeochemistry, Biogeochemistry, Environmental sciences, Forestry

Forest soil is known to be a source of the greenhouse gas N2O, but the impact of what is planted in that soil has long been overlooked. Here Machacova and colleagues quantify seasonal N2O fluxes from common boreal tree species in Finland, finding that all trees are net sources of this gas.

Introduction

With an area of about 1370 million ha, boreal forests comprise one-third of the global forested area1,2. Boreal forests cover much of the uppermost Northern Hemisphere (Canada, Russia, and Scandinavia). In Finland, they consist of a mosaic of different forest types, ranging from upland forests on mainly dry mineral soils with scattered small-scale peatland areas to peatlands with tree cover3. Boreal forests are considered a natural source of nitrous oxide (N2O), an important greenhouse gas with global warming potential of 298 over 100 years4. The net N2O emissions are estimated to be 0.38 kg ha−1 yr−1 based on predominant N2O production in the soil2. Even though N2O fluxes in boreal forests are lower compared to those of temperate and tropical forests (1.57 and 4.76 kg ha−1 yr−1)2, boreal forests play an important role in global N2O inventories due to their large area.

N2O is naturally produced within soils in a wide range of nitrogen (N) turnover processes, including mainly nitrification and denitrification processes, which can be closely interconnected. The denitrification processes are the only processes known to reduce N2O to N25–7. Generally, plants can contribute to ecosystem N2O exchange by taking up N2O from soil water and transporting it into the atmosphere through the transpiration stream8,9, by producing N2O directly in plant tissues10, by consuming N2O from the atmosphere by a non-specified mechanism11, and by altering the N turnover processes in adjacent soil12.

Recent research has revealed that not only herbaceous plants but also some tree species can be significant N2O sources13,14. High N2O emissions have been detected, however, only in the laboratory from seedlings grown under conditions of artificially increased N2O concentrations in soils8,9,15,16. Ecologically relevant studies with mature trees growing in natural field conditions are rare and have revealed only low N2O emissions13,14,17 or even consistent N2O consumption from the atmosphere11. Because these studies were often conducted without a full series of supporting environmental and physiological measurements, interpretation of the observed N2O fluxes is therefore limited.

Moreover, seasonal measurements of N2O fluxes are lacking, and particularly during the dormant season. Therefore, no information exists about possible seasonality of tree N2O fluxes. Another shortcoming is that calculation of annual N2O fluxes to date has been based solely on the results of short measuring periods during the vegetation season. It is well known that physiological activity of boreal trees is strongly reduced during winter, including photosynthetic CO2 assimilation, transpiration, and sap flow18,19. Transport of N2O in the transpiration stream has been suggested as one mechanism for N2O emissions from tree stems and canopies8,20. Also, possible N2O production in plant tissues during nitrate assimilation10,12,21–23 seems to be closely connected to photosynthesis, which is a process requiring sufficient light intensity, temperature, water, and mineral supplies. One must therefore conclude that lack of comprehensive understanding of the physiological and environmental drivers of variability in tree N2O flux leads to poor understanding of the N2O dynamics. The determination of N2O exchange rates of common tree species and their dynamics is of high importance for correct estimation of forest N2O budgets and therefore of global greenhouse gas flux inventories.

Accordingly, we hypothesised that tree-stem N2O fluxes have substantial seasonal dynamics in boreal forest and that the stem N2O fluxes are related to tree physiological activity as driven by such environmental variables as temperature, light intensity, and water availability. We quantified N2O fluxes of three dominant tree species—coniferous Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies L. Karst.), and broadleaved downy and silver birch (Betula pubescens Ehrh., B. pendula Roth.)—grown at plots naturally differing in soil volumetric water content (VWC). Seasonal N2O fluxes were measured on mature trees in southern Finland together with forest floor N2O and CO2 fluxes, numerous physiological parameters, and a range of environmental parameters describing meteorological, soil and atmospheric conditions. Stem CO2 effluxes as well as ecosystem gross primary productivity (GPP) and evapotranspiration were considered as indicators of physiological activity of the trees. Such a comprehensive experimental setup with multiple environmental variables measured together with N2O fluxes enabled us to investigate whether these tree species exchange N2O with the atmosphere, whether tree N2O fluxes have seasonal dynamics, whether trees exchange N2O during winter dormancy, whether N2O fluxes are related to environmental and physiological parameters, and how trees contribute to the net ecosystem N2O exchange. We discovered a strong seasonality in stem N2O exchange, which tightly relates to the physiological activity of the trees, in particular to CO2 uptake and release. We show that boreal trees exchange small amounts of N2O even during the dormant winter season. This unique dataset of whole-year N2O stem fluxes revealed boreal trees as net annual sources of N2O, with spruce being the strongest emitter. Our study thus provides a comprehensive overview of tree N2O flux dynamics and their environmental drivers in the soil—tree stem—atmosphere continuum.

Results and discussion

Stem N2O flux seasonality relates to physiological activity

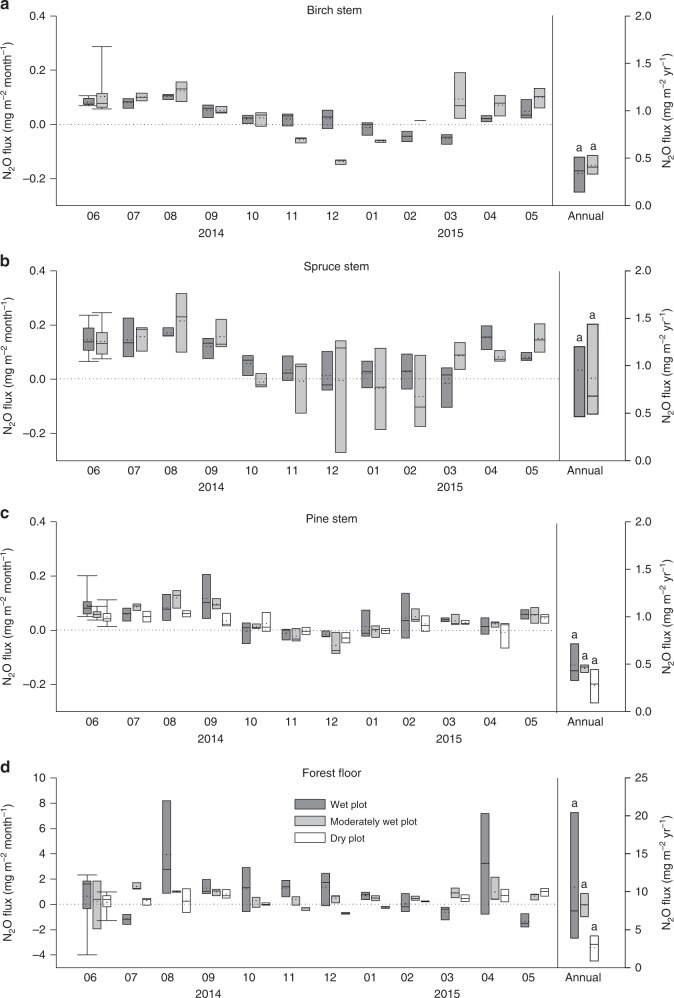

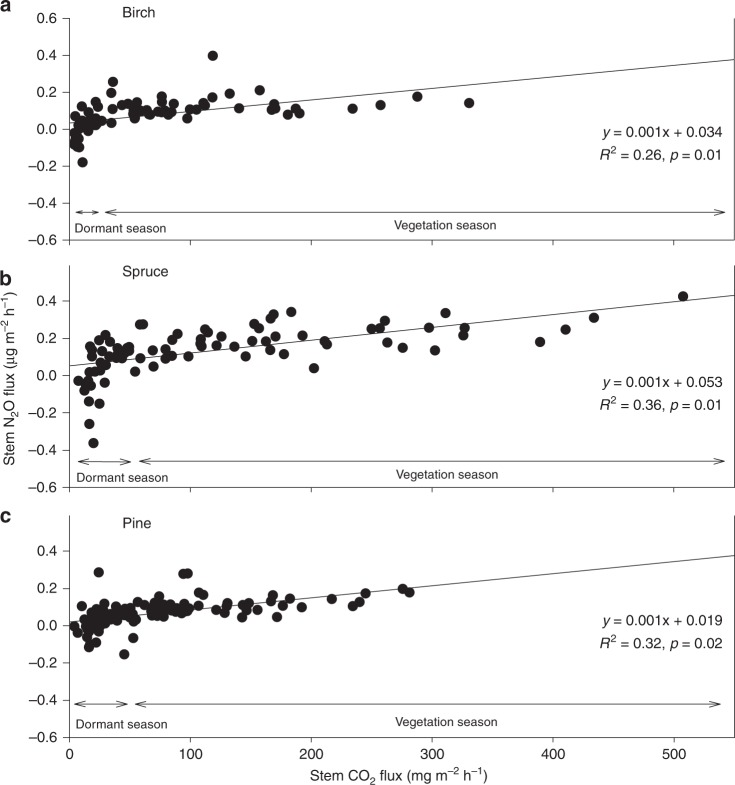

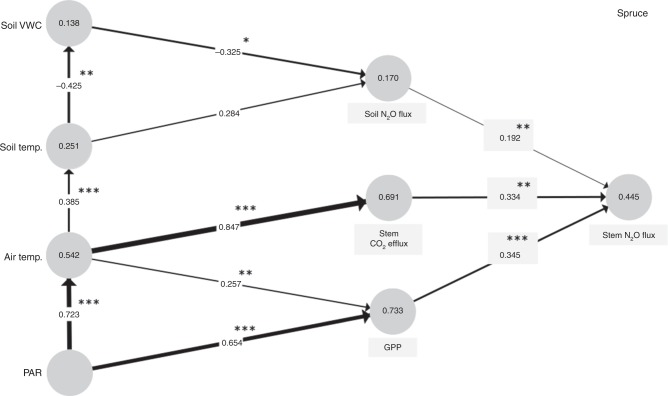

All boreal trees studied showed substantial seasonality in their N2O exchange. Previous rare studies have focused only on short periods of the vegetation season, excluding measurements in the dormant winter season. High and constant stem N2O emissions were observed from all the tree species studied during spring and summer months (April–September), independently of soil VWC. This was followed by a decrease from October onwards (Fig. 1). Tree fluxes remained low in winter and increased again in March. Stem CO2 effluxes revealed similar seasonality as did N2O fluxes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Seasonal dynamics of accompanying environmental parameters are presented in Fig. 2. A strong positive relationship between stem N2O and CO2 fluxes was detected (ρ = 0.714–0.745, depending on tree species; p < 0.001; Spearman’s rank correlation), and reduced flux rates were observed in the dormant season (Fig. 3). The positive relationship was further supported by a partial least squares (PLS) path analysis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Based on the results of the PLS path and correlation analyses, the second main driver of the stem N2O fluxes is the GPP of the forest (ρ = 0.543–0.660, p < 0.001; Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). For birch and pine, the stem CO2 efflux and GPP together explained 44% and 37%, respectively, of the variance in the stem N2O fluxes (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 1.

Stem and forest floor N2O fluxes. Seasonal courses of monthly N2O fluxes (mg m−2 month−1) and total annual N2O fluxes (mg m−2 yr−1) from stems of birch (a), spruce (b), and pine (c), and from forest floor (d) measured from June 2014 to May 2015. Positive fluxes indicate N2O emission, negative fluxes N2O uptake. The solid line within each box marks the median value, broken line the mean, box boundaries the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. Statistically significant differences among annual fluxes at p < 0.05 are indicated by different letters above bars. Mean annual volumetric water contents (± standard error) of the plots were as follow: wet plot, 0.81 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; moderately wet plot, 0.40 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; and dry plot, 0.21 ± 0.01 m3 m−3. The dry plot did not have spruce or birch trees. Stem fluxes were measured from three trees per species at each plot (n = 3). Forest floor fluxes were measured at three positions at the wet and moderately wet plots (n = 3) and at six positions at the dry plot (n = 6). Annual fluxes were calculated as the sums of 12 monthly fluxes

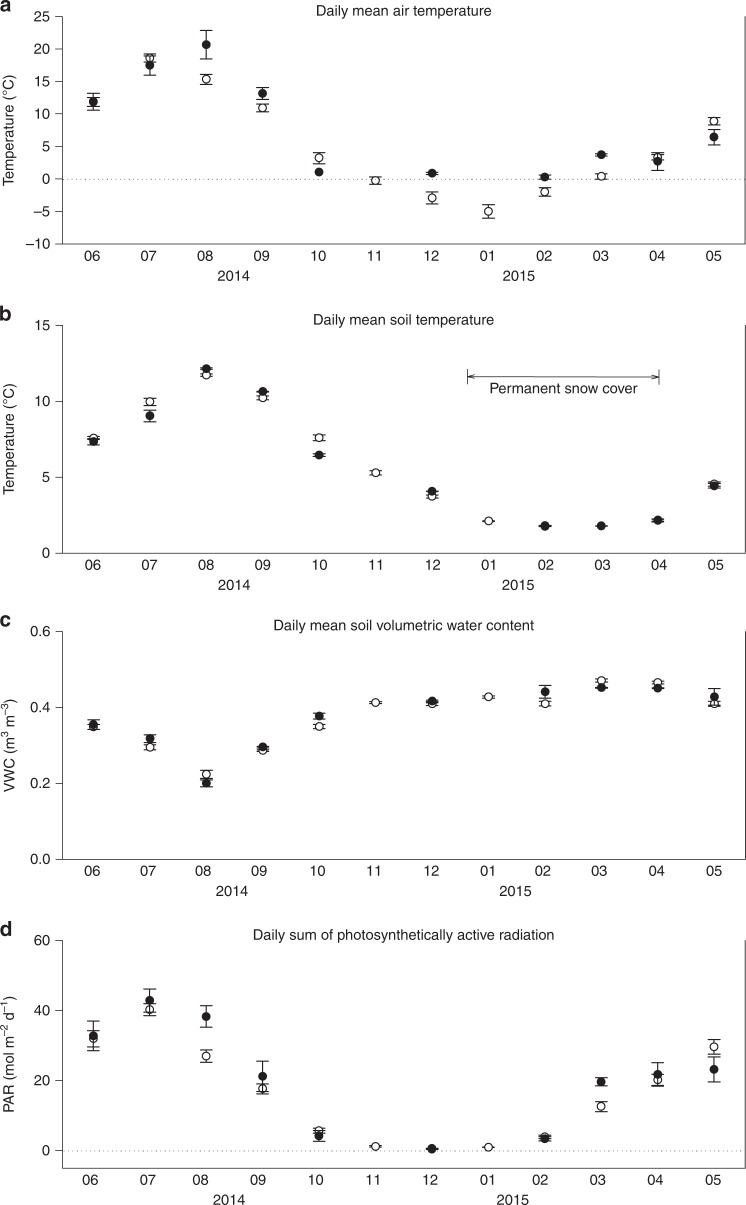

Fig. 2.

Seasonal courses of basic environmental variables. The variables were measured at the SMEAR II station from June 2014 to May 2015: (a) Daily mean air temperature within the forest stand at 8 m height; (b) daily mean soil temperature and (c) soil volumetric water content (VWC), both in C1-horizon (38–60 cm in depth); and (d) daily sum of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). The open circles represent monthly means (± standard error), and the black circles indicate monthly means ( ± standard error) calculated for the flux measurement days only. The period of continuous snow cover (from mid-December 2014 to early April 2015) is indicated in Fig. 2b

Fig. 3.

Relations between N2O and CO2 stem fluxes. N2O versus CO2 fluxes in stems of birch (a), spruce (b), and pine (c) measured from June 2014 to May 2015. Data for dormant (October–February) and vegetation (March–September) seasons are indicated. The stem fluxes were measured from three trees per species at three studied plots characterised by mean annual volumetric water content as wet (0.81 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; mean ± standard error), moderately wet (0.40 ± 0.02 m3 m−3), and dry (0.21 ± 0.01 m3 m−3). The dry plot did not have spruce or birch trees. All fluxes are expressed per m2 of stem surface area. Positive flux values indicate gas emission, negative values gas uptake

Fig. 4.

Prediction of N2O fluxes in spruce stem. Path diagram, created on the base of partial least squares path modelling, describes relationships among stem N2O fluxes and most predictive environmental, physiological, and ecosystem variables (drivers of N2O fluxes) for 2014–2015. Values in circles report coefficients of determination (R2). Values included in arrows mark the path coefficients, whose significance levels are expressed as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Soil volumetric water content (Soil VWC), photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), gross primary production (GPP). Soil N2O flux expresses forest floor N2O flux

From the available environmental variables, the stem N2O fluxes of all the studied tree species correlated positively (p < 0.001) with air temperature (ρ = 0.559–0.645), as well as intensities of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (ρ = 0.513–0.637) and ultraviolet (UV) radiation (ρ = 0.541–0.694). We also found strong positive correlation between the stem N2O fluxes and ecosystem evapotranspiration (ρ = 0.536–0.688, p < 0.001). That relationship was not proven by the PLS path analysis, however.

The relatively strong relationship between the stem N2O fluxes and those variables reflecting the physiological activity of the trees and ecosystem as a whole (stem CO2 efflux, GPP, evapotranspiration) suggests that the stem N2O fluxes do not constitute merely a passive process based on N2O concentration gradients in the soil–stem–atmosphere continuum. The possible coupling between N2O and CO2 fluxes was early detected in species belonging to cryptogamic covers11,24 and Spermatophyta11,25. This assumption is based on the finding of constant N2O:CO2 emission ratio under a wide range of controlled environmental conditions24,25. However, here we show for the first time a tight linear correlation between N2O and CO2 fluxes even in adult trees during the whole vegetation period (Fig. 3) supporting thus the hypothesis of physiologically dependent N2O exchange in tree stems.

The strong positive correlation with evapotranspiration supports our hypothesis that N2O is taken up from the soil by roots, then transported into the above-ground tree tissues in xylem via the transpiration stream. This hypothesis is supported also by the good solubility of N2O in water26 and the demonstrated ability of plants lacking the aerenchyma system8,9,13 to transport N2O from the soil and emit it through the stem. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that N2O exchange by mature boreal tree stems is closely connected to the physiological activity of trees and ecosystem, particularly to processes of carbon release and uptake, including stem CO2 efflux and GPP. Future experimental studies are needed, however, to confirm that transpiration rate drives N2O emissions from tree stems.

Forest floor N2O flux together with the stem CO2 efflux and GPP explained 45% of the stem N2O flux variance in spruce (Fig. 4). Spruce was the only tree species manifesting a weak relationship between stem and forest floor N2O fluxes (ρ = 0.353, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Similarly, a positive but weak correlation between stem and forest floor N2O fluxes was found earlier in pine trees grown in the same forest13. Lack of strong correlations indicates a partial decoupling of stem and forest floor N2O fluxes. Generally, net fluxes at the tree stem/soil–atmosphere interface reflect a balance between processes of production, consumption, and transport of N2O within trees and soil from the sites of production to the sites of release27. Accordingly, substantial variation in root depth among tree species can contribute to observed species specificity in N2O fluxes. The net forest floor N2O flux does not necessarily reflect the N2O concentration or production/consumption in the rooting zone11, because the plants can directly alter soil microbiological N turnover processes28–31 by modifying the quantity and quality of soil organic matter, nutrient availability, and soil pH29,32. This includes release of exudates33 and radial oxygen loss34 from the roots, which are again closely connected to such tree physiological processes as photosynthesis35. Furthermore, leaf and root litter quality and soil water uptake by trees, both of which are specific to tree species, can substantially affect the N cycling processes in soils28. Production of N2O in soil is further directly and indirectly influenced by an activity of mycorrhizal fungi via the modulation of denitrification processes and physio-chemical soil properties regulating N2O turnover like carbon, nitrogen, and water availability, as well as soil aeration and promotion of soil aggregation, respectively36–39. Mycorrhizal fungi itself seem to possess also the ability for denitrification and might be therefore important sources of N2O36,38. Due to these strong rhizospheric effects of plants and mycorrhizal fungi on soil N turnover processes, the ratio between N2O production and consumption in the soil might also be highly variable. Hence, the availability of N2O in the rhizosphere affects the N2O uptake by tree roots and subsequent N2O emissions from tree surfaces into the atmosphere, and that might not be reflected in the overall net N2O exchange at the soil surface.

In addition to that of soil origin, N2O emitted by trees can also be formed directly in the tree tissues. The direct N2O production in plants is proposed to originate from microorganisms living in association with the plants36, as described earlier with mycorrhizal associations, or from N2O produced via photo-assimilation of NO3− in photosynthetically active tree tissues10,21,22, or via a newly detected biotic pathway with mechanisms different from known microbial or chemical processes25, or via an abiotic UV-dependent process on leaf surfaces40. The plant’s own N2O production process seems to be light dependent, requiring energy from primary photosynthetic reactions10,12,23. The mechanisms and processes behind radiation induced N2O emissions are still poorly understood, however, and especially with respect to mature trees. Moreover, the possible contributions of the various N2O production processes in plants to the net N2O fluxes at the tree–atmosphere continuum are largely unknown. To the best of our knowledge, only Machacova et al.13 have reported N2O emissions from leaves of mature trees and showed that the leaf emissions might considerably exceed the emissions from the stems and could therefore constitute an additional source of N2O in forest ecosystems13.

In conclusion, the N2O emission rates from tree stems show clear seasonal dynamics with the highest emissions detected during summer months when also air temperature, PAR and UV intensities are the highest. The seasonal changes in N2O emission closely relate to the physiological activity of trees associated with CO2 exchange as demonstrated by a tight linear correlation between N2O and CO2 fluxes.

Boreal trees exchange N2O even during dormant season

Based on the seasonal changes in stem CO2 efflux (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c), the period from October to February was identified as a dormant season. In addition to the vegetation-season N2O emissions, our study revealed that all the studied tree species can emit N2O even during the dormant season, and particularly on the plot characterised by high soil VWC (i.e. the wet plot). At this plot, the stem N2O emissions over the dormant season contributed from 2% (birch) to as much as 16% (spruce) to the annual N2O emissions (Fig. 5a‒c).

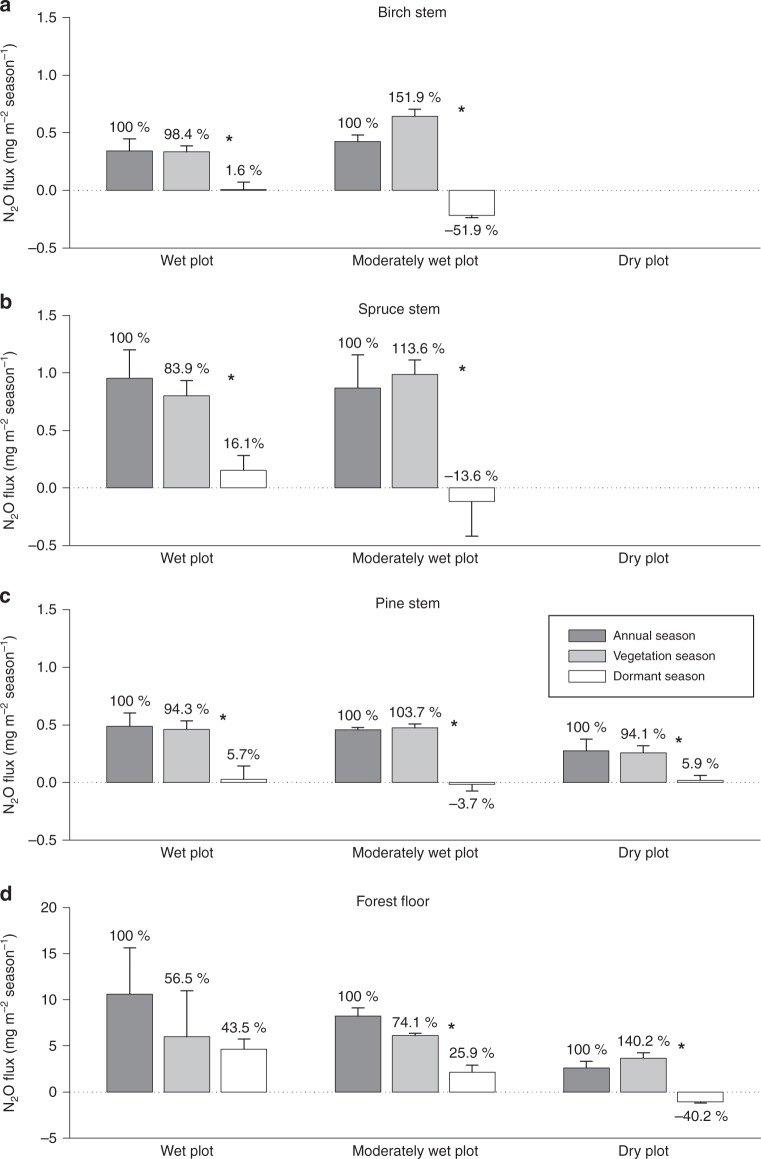

Fig. 5.

Seasonal N2O fluxes in tree stems and forest floor. N2O fluxes in stems of birch (a), spruce (b), and pine (c), and in forest floor (d) are presented at annual scale (black columns), for vegetation season (March–September, grey columns), and for dormant season (October–February, white columns). The fluxes (means ± standard error) are sums of N2O exchanged over one year, vegetation season, or dormant season, respectively, and expressed per m2 of stem or soil surface area. Positive flux values indicate N2O emission, negative values N2O uptake. Mean annual volumetric water contents ( ± standard error) of the plots were as follow: wet plot, 0.81 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; moderately wet plot, 0.40 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; and dry plot, 0.21 ± 0.01 m3 m−3. The dry plot did not have spruce or birch trees. Stem fluxes were measured from three trees per species at each plot (n = 3). Forest floor fluxes were measured at three positions at the wet and moderately wet plots (n = 3) and at six positions at the dry plot (n = 6). Statistically significant differences between fluxes over vegetation and dormant season at p < 0.05 are indicated by asterisks. The percentage contributions of fluxes over the vegetation and dormant season to the annual fluxes (defined as 100%) are indicated above the bars

The small but detectable winter N2O fluxes of the tree stems were accompanied by low but consistent CO2 emissions from the stems (Supplementary Fig. 4a‒c), thereby reflecting the rate of maintenance respiration during the dormant period41. This is supported by the fact that air temperatures were generally mild on the measurement days (Fig. 2a). It has been shown that stem CO2 effluxes in boreal trees decrease significantly during winter periods, when stems are frozen42. Large amounts of CO2 can nevertheless be released in short-term CO2 burst events during freezing and thawing of tree stems and thus contribute significantly to the seasonal CO2 dynamics42. We did not observe such bursts during autumn measuring campaigns when the air temperature was above zero, but slightly elevated stem CO2 fluxes during February (pine) and March (birch, spruce) might indicate CO2 bursts from freezing and thawing tree stems (Supplementary Fig. 1). The stem N2O flux dynamics, albeit at comparatively lower rates, follow a similar seasonality in spring (Fig. 1), thus supporting the idea that both CO2 and N2O originate from a similar source. Both gases dissolved in the xylem sap might be released from the stem during freezing to avoid winter embolism in the xylem conduit and during thawing from the intercellular spaces, where gases can be trapped during the process of stem freezing42.

On plots characterised by lower soil VWC, the stems even consumed N2O from the atmosphere during the dormant season, thus contributing to reduction of the annual source strength of trees and the ecosystem as a whole (Fig. 5a–c). Birch was identified as the strongest N2O sink. Dormant uptake by birch stems amounted to as much as 52% of the annual N2O emissions at the moderately wet plot (Fig. 5a). We speculate that the species variability in N2O exchange (Figs. 1, 5) might be explained by spatial variability of N2O concentration in soil, which is more pronounced under lower soil VWC. Under such conditions, N2O sources are more diverse due to simultaneously running aerobic and anaerobic N turnover processes leading to production and consumption of N2O. Under dry conditions, therefore, root depth and distribution seem to play a more important role, species specificity is more pronounced, and differences among individual trees having different N2O sources available also are more prominent. This hypothesis should be confirmed by further research.

To the best of our knowledge, the limited number of studies reporting N2O exchange of tree stems present trees only as N2O emitters13,14. The only tree species known able consistently to take up N2O from the atmosphere is European beech11. That species’ cryptogamic stem covers were shown to be organisms that might be co-responsible for beech’s uptake of N2O. In their study, Machacova et al. (2017)11 observed that N2O consumption rates were closely related to the respiratory CO2 fluxes of trees and cryptogams, thus indicating a connection between N2O consumption and the physiological activity of trees and microbial communities. Our observed N2O consumption by boreal tree stems is probably not linked to the physiological activity of the cryptogams associated with the tree bark, because during the dormant season any physiological activity in the forest is very low, as evidenced by the negligible stem CO2 effluxes. We hypothesise that the reason for high N2O uptake observed in birch trees might be that birch trees, in contrast to the studied conifers, possess an aerenchyma system serving as a passive gas transport pathway within the tree43. Under low winter N2O concentration in soil, the broadleaf birch trees might hypothetically take up N2O from the atmosphere through lenticels in the bark, transport this gas along the concentration gradient into the roots, then perhaps release it into the soil at the root tips lacking exodermis. In contrast to the wood of conifers, that of the birches is a diffuse-porous type44 that is more gas-permeable45. The N2O might also be reduced by denitrifiers directly in stem tissues below the lenticels, although such microbial activity would be decreased in wintertime6,46. At least in the case of Betula potaninii, it seems also that the vapour phase-based water and oxygen permeance of individual lenticels is significantly reduced during wintertime due to the production by phellogen of compact tissues closing off lenticels at the end of the vegetation season. These tissues lacking intercellular spaces reduce gas exchange between the atmosphere and the system of intercellular spaces within the stem47. Hence, the mechanisms behind the uptake of N2O by trees and the fate of N2O remain unknown.

Similarly to the tree stem fluxes, the forest floor was a source of N2O in the vegetation season independently of the soil VWC (Fig. 5d). The rates of N2O emission were in line with those reported earlier for the same forest48. The similarly elevated emissions at all the studied plots in September (Fig. 1d) might be connected to litterfall, which is regarded as the largest external N input to the soil and hence suggested to stimulate N2O formation in the soil48. The forest floor fluxes subsequently decreased in the dormant season, which was in accordance with our earlier findings48. The effect of soil VWC on N2O fluxes was most pronounced during the dormant season, when N2O consumption was observed in the soils with low VWC (0.21 m3 m−3; i.e. dry plot; Fig. 5d). This N2O consumption reduced the annual forest floor N2O emissions by 40% at the dry plot (Fig. 5d). Nevertheless, forest floor N2O consumption was occasionally observed at all the plots throughout the year (Fig. 1d). Even though the CO2 emissions from the forest floor also were significantly lower in the dormant season compared to the vegetation season (Supplementary Fig. 1d, 4d), these were still detectable.

In summary, during the dormant season, the tree stems and forest floor remain sources of N2O at plots characterised by high soil VWC, whereas tree stems act as N2O sinks under moderately wet soil water conditions. During the vegetation season, however, the soil VWC does not affect the N2O emissions from either trees or forest floor. Hence, our results highlight the need for winter flux measurements in order to correctly estimate the overall N2O budget of boreal forests.

Boreal trees are net annual N2O emitters

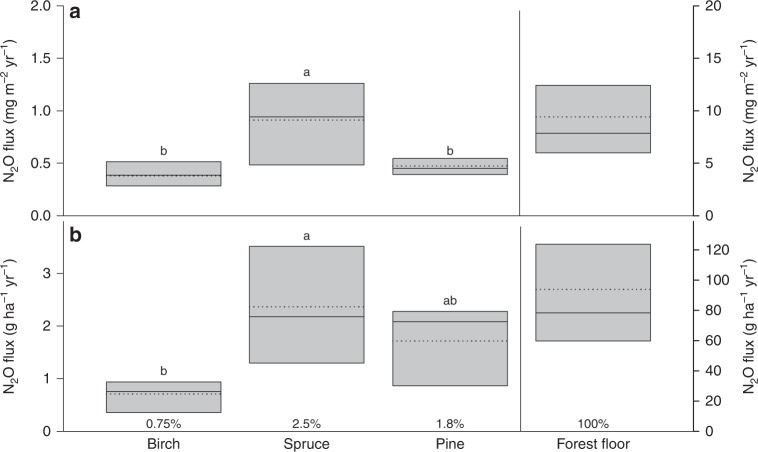

All the tree species studied were net sources of N2O at the annual scale (Fig. 6). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting annual course of N2O fluxes in boreal trees to include winter measurements. Neither the stem nor the forest floor N2O emissions were significantly influenced by the soil VWC at the annual scale (Fig. 1). Therefore, measurements at the wet and moderately wet plots, where all the species were present, were merged to evaluate the tree species-specific fluxes at the annual scale. The measurements at the dry plot were not included into this comparison because only pine trees were present there. Spruce was the strongest emitter of N2O, with total emission per year of 0.91 mg N2O m−2 stem area and 2.4 g N2O ha−1 ground area, followed by pine (0.47 mg m−2 and 1.7 g ha−1) and birch (0.38 mg m−2 and 0.71 g ha−1) (Fig. 6). The forest floor emitted in total 9.4 mg N2O m−2 soil area per year (i.e. 93.9 g ha−1 per year), which is consistent with the annual N2O emissions of 8.8 mg N2O m−2 yr−1 estimated for the same forest during the years 2002–200348.

Fig. 6.

Annual N2O fluxes in tree stems and forest floor. The fluxes are expressed per stem or soil surface area unit (a) and scaled up to unit ground area of boreal forest (b). The fluxes are expressed as medians (solid line) and means (broken line) of measurements at both wet and moderately wet plots together, as the N2O fluxes did not vary significantly between those plots at the annual scale. The dry plot was not included into this comparison of annual fluxes because only pine trees were available at this plot. The stem fluxes were measured from six trees per species (n = 6), the forest floor fluxes were determined at six positions (n = 6). The box boundaries mark the 25th and 75th percentiles. Statistically significant differences in annual fluxes among birch, spruce and pine at p < 0.05 are indicated by different letters above the bars. The contributions of stem fluxes to forest floor N2O fluxes (equal to 100%) are expressed as percentages of the forest floor flux

Based on the topographic wetness index (TWI) at the site, the dry plot represents 48%, the moderately wet plot 37%, and the wet plot 11% of the forest (remaining 4% accounting for standing water, Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, we estimate that the annual emissions from the wet and moderately wet plots together represent ca 50% and the emissions from the dry plot ca 50% of the total forest fluxes, respectively. As we have demonstrated that the tree stem N2O fluxes are not controlled by soil water content at the annual scale, we confidently can conclude that the site type does not play a critical role in stem N2O fluxes.

Moreover, the differences in ecosystem level fluxes may result from tree species composition of the forest. As we found that spruce tree stems emitted significantly more N2O than did pine and birch stems, spruce-dominated forests are predicted to emit more N2O than pine- or birch-dominated forests. The contribution of tree species to the forest floor N2O emissions was relatively low, however, amounting to 2.5, 1.8, and 0.75% for spruce, pine, and birch, respectively (Fig. 6) when the certain representation of tree species at each plot (Table 1) was included in upscaling. In Finland, Scots pine is the dominant tree species, accounting for 78% of forest land area coverage, while only 15% is covered by Norway spruce49. Our finding of the N2O emissions from spruce trees can be important for the estimation of N2O budget not only in boreal forests but also in temperate forests of Central Europe, where spruce is widely grown in monoculture50. Spruce trees’ stronger capability to exchange N2O with the atmosphere may be related to their physiological activity. In our study, spruces had the highest projected leaf area per tree (88 m2 on average) among the tree species studied (birch 54 m2, pine 28 m2). Greater leaf area results in larger amounts of CO2 assimilated and H2O transpired per spruce tree than per pine or birch tree. The greater physiological activity of spruce is further reflected in the higher annual sum of stem CO2 efflux amounting to 0.867 kg CO2 m−2 and 2303 kg ha−1, compared to 0.590 kg CO2 m−2 (2140 kg ha−1) and 0.427 kg CO2 m−2 (738 kg ha−1) for pine and birch trees, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). Ge et al.51 presented the same conclusion from their study of different boreal tree species. The variation in N2O emission rates among plant species also can result from plants’ effects on soil N2O production and consumption, which can themselves differ significantly among species, rather than from different transpiration rates or direct plant production of N2O in plant tissues52. Although deciduous tree species tend to increase soil N2O production more so than do conifers29,30, the effects of individual tree species are not uniformly presented among studies. Further research is therefore needed to understand the observed differences in N2O emission rates among tree species.

Table 1.

Stand characteristics and tree biometric parameters

| Tree height (m) | DBH (m) | Stem surface area (m2) | Forest density (trees ha−1) | Stand basal area (m2 ha−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birch (Betula pendula and B. pubescens) | |||||

| W plot | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1200 | 6 |

| MW plot | 22.1 ± 0.7 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 200 | 4 |

| Spruce (Picea abies) | |||||

| W plot | 14.5 ± 4.4 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 4.2 ± 2.3 | 400 | 4 |

| MW plot | 21.2 ± 1.0 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 400 | 5 |

| Pine (Pinus sylvestris) | |||||

| W plot | 18.2 ± 1.3 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 400 | 20 |

| MW plot | 20.6 ± 0.4 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 800 | 21 |

| D plot | 18.7 ± 0.7 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 1400 | 27 |

All variables (mean ± standard deviation) are related to birch, spruce, and pine trees at wet (W), moderately wet (MW), and dry (D) plots. The dry plot did not have spruce or birch trees. Trees were approximately 50 years of age, except for three birches and one spruce on the wet plot, which were unambiguously younger. The forest density is defined as number of individual trees per tree species and area unit of individual experimental plots. Stem diameter at breast height (DBH). Table modified after ref. 68

Lack of canopy level N2O flux measurements brings additional uncertainty in the forest ecosystem N2O budget. Based on our previous research, we have shown that the leaf emissions by pine trees could exceed those of stems by as much as 16 times13. We therefore expect that boreal tree species might contribute even more significantly to the forest N2O exchange. Although measurements of above-canopy N2O exchange in forest ecosystems using such micrometeorological techniques as eddy covariance, eddy accumulation, or flux gradient methods have been used only rarely53–55, these could improve our view in the future.

We have demonstrated that N2O emissions from tree stems are driven by physiological activity of the trees and by ecosystem activity, showing higher emissions during the active growing period and variation between uptake and emissions during the dormant season. Although our study may well be applicable to large upland forest areas in the boreal zone, which are typically N limited56, our findings may not apply directly in N-affected central European or American forests known to exhibit elevated soil N2O emissions due to higher soil N content and faster N turnover rates57–59. The N status of a forest directly influences soil N2O concentration, which has been shown to be a good proxy for N2O transport via the transpiration stream of trees8. Until more studies and process understanding emerge, the global strength of N2O emissions from trees will remain largely unknown and could possibly be estimated by, for example, adding a fixed percentage (e.g. 10%) to the forest floor N2O emissions to represent N2O emission from trees.

In summary, we have shown that all widespread boreal tree species are net annual sources of N2O, with spruce being the strongest emitter. The highest stem emissions were detected during summer, but remained detectable also during winter dormancy. Seasonal changes in N2O fluxes tightly correlate with changes in CO2 fluxes, which are particularly driven by temperature and light intensity. The physiological processes of trees thus could be used as indicators of the N2O flux dynamics in boreal forests. Furthermore, our results unequivocally indicate necessity to include seasonality of N2O exchange into global models and forest ecosystem process models to determine comprehensive total flux estimates.

Material and methods

Site description and experimental design

The measurements were performed in boreal forest near the SMEAR II station (Station for Measuring Ecosystem–Atmosphere Relations) at Hyytiälä, southern Finland (61°51′ N, 24°17′ E, 181 m a.s.l.) from June 2014 until May 2015. The long-term annual mean temperature and precipitation for this site are 3.5 °C and 711 mm, respectively60. Seasonal courses of basic environmental variables during the period studied are shown in Fig. 2. The highest mean daily air temperatures within the forest stand were 24 °C in July and 23 °C in August and the lowest −18 °C in December and −15.5 °C in January (Fig. 2a). Soil temperature in the C1-horizon corresponding to the depth of 38–60 cm was lowest in February and March (between 1.7 and 1.9 °C) and highest in August (12.2 °C, Fig. 2b). There was a continuous snow cover between mid-December and early April (Fig. 2b). Soil VWC (Fig. 2c) in the C1-horizon was lowest in August, remained rather constant between November and April, but was highest in March. The seasonal course for the daily sum of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR; Fig. 2d) has a pattern typical for boreal ecosystems.

The studied mixed forest is dominated by P. sylvestris, with P. abies, B. pubescens, and B. pendula as other abundant species. The forest is heterogeneous in soil type and characteristics (Haplic podzol on glacial till with some paludified organic soil), tree species and understorey vegetation composition, and forest structure. Such heterogeneities accordingly lead to heterogeneity in soil VWC (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Three plots naturally differing in soil VWC—wet (0.81 ± 0.02 m3 m−3; mean ± standard error), moderately wet (0.40 ± 0.02 m3 m−3), and dry (0.21 ± 0.01 m3 m−3)—were selected for this study. Three representative trees of pine, spruce, and birch were chosen per plot (n = 3) for stem flux measurements, except that at the dry plot only P. sylvestris was present. Characteristics of the representative trees are shown in Table 1. Forest floor N2O and CO2 fluxes were measured at three representative positions on both the wet and moderately wet plots (n = 3) and at six positions on the dry plot (n = 6). The ground vegetation at the wet plot was dominated by Sphagnum sp. followed by Polytrichum commune and Equisetum sylvaticum. Some Comarum palustre, Trientalis europae, and Carex digitata were also present in the soil chambers. The dominating species in the chambers at the moderately wet plot were Hylocomium splendens, P. commune, and Sphagnum sp. Also common were Pleurozium schreberi, Dicranum polysetum, Vaccinium vitis-idaea, Vaccinium myrtillus, and Rubus saxatilis. At the dry plot, the dominant species were V. vitis-idaea, V. myrtillus, H. splendens, and P. schreberi.

Stem and forest floor fluxes of N2O and CO2 were measured simultaneously at each plot. Acquiring one measurement set from all three plots required 1–2 weeks, and all the plots were measured at least once per month. The most intensive measurement periods were the main vegetation season (June–August), when the flux measurements were repeated six times, and February, with two repetitions. Adverse conditions did not allow flux measurements in November and January, and thus fluxes for these months were estimated using a linear interpolation of fluxes from adjacent months. All fluxes were determined between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. of non-precipitating days to prevent possible effect of diurnal cycle. The means of air and soil temperature, soil VWC, and PAR for flux measurement days of each month are shown in Fig. 2.

Stem flux measurements

The fluxes of N2O and CO2 at the bottom part of the stems (approximately 20 cm above the soil) were measured manually using two different types of static chamber systems: box and circumferential chambers. The chambers were installed in May 2014. The box chambers11,61 consisted of transparent plastic containers with removable airtight lids (Lock & Lock, Anaheim, CA, USA) and a neoprene sealing frame. They were gas-tightly affixed to the carefully smoothed bark surface using silicone. Per each tree, two rectangular box chambers (total area of 0.0176 m2 and total internal volume of 0.0012 m3) were installed at one stem height on opposite sides of the stem and interconnected with polyurethane tubes into one flow-through chamber system (for more details see Machacova et al.11). The circumferential chambers were as described by Machacova et al.13 with slight modification. The chambers consisted of a wire skeleton and a tube-fitting brace for inlet and outlet connectors which were wrapped six times with a plastic stretch foil to form the chamber wall. The top and bottom ends of the foil were sealed with neoprene, silicone, and cable ties to the carefully smoothed bark (for details see Machacova et al.13). The internal volume of the circumferential chambers ranged between 0.0030 and 0.0054 m3 and the stem surface area covered by the chamber ranged between 0.083 and 0.258 m2, depending on stem diameter. Mixing of the air inside both chamber systems was produced via air circulation by gas pumps (DP0140/12 V, Nitto Kohki, Tokyo, Japan; NMP 850.1.2., KNDC B, KNF Neuberger, Freiburg, Germany). Fans (412 FH, ebm-papst, Mulfingen, Germany; KF0410B1H, Jamicon, Kaimei Electronic Corp., New Taipei City, Taiwan) in circumferential chambers enhanced the mixing process. The two different chamber types were equally distributed among the studied tree species, although box chambers were mostly installed on spruces because an abundance of lower branches typical for spruces prevented installation of circumferential chambers. The results obtained from the two different stem chamber systems were comparable. Gas-tightness of all the chambers was regularly tested throughout the year.

For the flux measurements, nine gas samples (each 20 mL) were taken via a septum at 0, 30, 60, 90, 130, 170, 220, 270, and 320 min after closure of the chamber system and stored in pre-evacuated gas-tight glass vials (Labco Exetainer, Labco, Ceredigion, UK). The possible changes in air pressure within chambers were compensated by the flexible wall reducing an internal volume of circumferential chambers and by simultaneous injection of ambient air into the box system. The box chambers were left open between the measuring campaigns, but the circumferential chambers were left closed between the measurements on following days. In the latter case, the chamber headspace was washed with ambient air for at least 30 min prior to the flux measurement. The monitored CO2 concentration in the chambers provided an indicator as to when the washing of the chambers was sufficient.

Forest floor flux measurements

Forest floor N2O and CO2 fluxes were measured using two soil chamber types differing in their internal volumes. At the wet and moderately wet plots, three large manual aluminium opaque chambers (internal volume between 0.092 and 0.140 m3, depending on vegetation cover, soil surface area of 0.298 m2) described as chamber n. 13 by Pihlatie et al.62 were used. At the dry plot, the forest floor fluxes were determined by six smaller manual stainless steel opaque chambers (internal volume 0.020 m3, soil surface area 0.116 m2)48. The collars of all chambers were installed in 2013 or earlier in the vicinity of the investigated trees. A fan (412 FH, ebm-papst, Germany; KF0410B1H, Kaimei Electronic Corp., Taiwan) was used to mix the air inside all chambers.

The large soil chambers were closed for ca 75 min during which gas samples (65 mL each) were taken at time intervals of 1, 5, 15, 25, 35, 55, and 75 min. The gas sampling intervals from the small soil chambers at the dry plot were set to 1, 5, 15, 30, and 45 min after the time of closure. All gas samples were transferred from syringes to glass vials (Labco Exetainer) until the analysis by gas chromatograph.

Gas analyses

The gas samples were stored in gas-tight glass vials at 7 °C and analysed by an Agilent 7890 A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA)62. The gas chromatograph was equipped with an electron capture detector for N2O analyses, and a flame ionisation detector for CO2 detection. The electron capture detector (operating at 380 °C) was supplied with argon/methane (15 mL min−1) as a make-up gas. The flame ionisation detector (operating at 300 °C) was run with synthetic air (450 mL min−1) and hydrogen (45 mL min−1), with nitrogen (5 mL min−1) as a make-up gas. Helium (45 mL min−1) was used as a carrier gas. Porapak Q 80-100 and HayeSep Q 80-100 mesh columns (Agilent Technologies) were used for water vapour removal and gas separation. Oven temperature was maintained at 60 °C during analyses. The gas samples were injected automatically using a GX-271 autosampler (Gilson Liquid Handler, Middleton, Wisconsin, USA). ChemStation B.03.02 software (Agilent Technologies) was used to control the chromatograph system and analyse the data.

The N2O and CO2 concentrations in gas samples were calculated based on a four-point concentration calibration curve (0.31, 0.34, 0.36, and 0.39 µmol N2O mol−1; 400, 733, 1067, and 1500 µmol CO2 mol−1). The standards were analysed at the beginning of each run and after every ca 27 gas samples. Standard samples (0.34 µmol N2O mol−1, 733 µmol CO2 mol−1) were applied after every ca 9–18 samples to detect possible drifts occurring during the analysis.

Flux calculation

The stem and forest floor fluxes were quantified based on the linear N2O and CO2 concentration changes in the chamber headspace over time (for the equation, see Machacova et al.13). The stem and forest floor monthly fluxes were calculated as mean daily fluxes of a given month multiplied by the number of days for each of the months. The annual and seasonal fluxes were calculated as sums of monthly fluxes. Missing fluxes were estimated using linear interpolation of fluxes from adjacent months (for November, January) or as the mean of flux rates simultaneously detected from adjacent chambers. The annual fluxes were further scaled up to those for 1 ha of a boreal forest with characteristics of the studied plots. An extrapolation was based on mean stem surface area, tree density, and stand basal area, all estimated for each individual tree species and plot (Table 1). The upscaling procedure is described in Machacova et al.13.

Ancillary measurements

Interpretation of the flux data was based on the seasonal dynamics of environmental parameters, including in particular soil water content and temperature, air temperature, and radiation intensity. The soil water content and soil temperature were measured close to the studied trees and soil chambers in the A-horizon (0–5 cm soil depth) using a manual HH2 Moisture Meter with Theta Probe (ML2x, AT Delta-T Devices, Cambridge, UK) and continuously running DS1921G Maxim Thermochron iButtons (Maxim Integrated, San Jose, California, USA), respectively. In addition, the following environmental and ecosystem parameters, which continuously are determined at the SMEAR II station, were used for further non-parametric correlation and PLS path analyses: soil water content (TDR100, Campbell Scientific, North Logan, Utah, USA) and soil temperature (Philips KTY81/110, NXP, Eindhoven, Netherlands) in the C1-horizon (38‒60 cm soil depth)63,64; air temperature at 8 m height within the forest stand (Pt100 sensors, with radiation shield by Metallityöpaja Toivo Pohja); relative humidity at 16 m height (MP102H RH sensor, Rotronic AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland); PAR at 18 m height (Li-190SZ, Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA); UV A and B radiation at 18 m height (SL501A radiometer, Solar Light Company, Glenside, Pennsylvania, USA); net ecosystem exchange of CO2 (measured by eddy covariance method65); GPP (derived from net ecosystem exchange); and evapotranspiration at 23 m height (measured by eddy covariance method, with gaps in the measured H2O flux time series filled using linear regressions of flux on net radiation66,67).

Statistics

The flux data were tested for normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test) and equality of variances in different subpopulations; t-test and one-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons were applied for normally distributed data. Non-parametric Mann‒Whitney rank sum test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks for multiple comparisons were applied for non-normally distributed data and/or data with unequal variances. The n values for statistical analyses are stated in the figure legends. Detailed non-parametrical Spearman correlation analyses and PLS path modelling of N2O fluxes were carried out. Hence, tree stem and soil N2O fluxes were compared to CO2 fluxes, soil temperature and soil water content measured adjacent to the trees and soil chambers, and to the aforementioned environmental and ecosystem parameters continuously measured at the SMEAR II station. Statistical significance of all tests was defined at p < 0.05. The statistics were run using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, California, USA), Python scripts and SmartPLS 3 software (SmartPLS, Boenningstedt, Germany).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (17-18112Y), the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic within the National Sustainability ProgramI (grant number LO1415), EU FP7 project ExpeER (Grant Agreement 262060), Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Academy of Finland Research Fellow projects (292699, 263858, 288494), The Academy of Finland Centre of Excellence (projects 1118615, 272041), ICOS-Finland (281255), and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement 757695). We thank Marian Pavelka, Jiří Dušek, Stanislav Stellner, Jiří Mikula, Marek Jakubík, Janne Levula and Matti Loponen for technical support and Uwe Großmann for IT support in data processing.

Author contributions

K.M. and M.P. had the idea for the study. K.M., M.P. and E.V. designed the study. K.M. and E.V. carried out the field measurements and analysed the data. K.M., M.P., E.V. and O.U. contributed to writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Lucie Jerabkova, Katharina Lenhart and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-12976-y.

References

- 1.Kuusela K. The boreal forests: an overview. Unasylva. 1992;170:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalal RC, Allen DE. Turner Review No. 18: Greenhouse gas fluxes from natural ecosystems. Aust. J. Bot. 2008;56:369–407. doi: 10.1071/BT07128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korhonen, K. T. et al. Suomen metsät 2004–2008 ja niiden kehitys 1921–2008. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 3/2013, 269–608 (2013).

- 4.IPCC. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- 5.Wrage N, Velthof GL, van Beusichem ML, Oenema O. Role of nitrifier denitrification in the production of nitrous oxide. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001;33:1723–1732. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00096-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith KA, et al. Exchange of greenhouse gases between soil and atmosphere: interactions of soil physical factors and biological processes. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2003;54:779–791. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-0754.2003.0567.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rütting T, Boeckx P, Müller C, Klemedtsson L. Assessment of the importance of dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium for the terrestrial nitrogen cycle. Biogeosciences. 2011;8:1779–1791. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-1779-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pihlatie M, Ambus P, Rinne J, Pilegaard K, Vesala T. Plant-mediated nitrous oxide emissions from beech (Fagus sylvatica) leaves. New Phytol. 2005;168:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machacova K, Papen H, Kreuzwieser J, Rennenberg H. Inundation strongly stimulates nitrous oxide emissions from stems of the upland tree Fagus sylvatica and the riparian tree Alnus glutinosa. Plant Soil. 2013;364:287–301. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1359-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smart DR, Bloom AJ. Wheat leaves emit nitrous oxide during nitrate assimilation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7875–7878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131572798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machacova K, Maier M, Svobodova K, Lang F, Urban O. Cryptogamic stem covers may contribute to nitrous oxide consumption by mature beech trees. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13243. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13781-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu, K. & Chen, G. in Nitrous Oxide Emissions Research Progress (eds Sheldon, A. I. & Barnhart, E. P.) 85–104 (Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2009).

- 13.Machacova K, et al. Pinus sylvestris as a missing source of nitrous oxide and methane in boreal forest. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23410. doi: 10.1038/srep23410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen Y, Corre MD, Rachow C, Chen L, Veldkamp E. Nitrous oxide emissions from stems of alder, beech and spruce in a temperate forest. Plant Soil. 2017;420:423–434. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3416-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rusch H, Rennenberg H. Black alder (Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn.) trees mediate methane and nitrous oxide emission from the soil to the atmosphere. Plant Soil. 1998;201:1–7. doi: 10.1023/A:1004331521059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBain MC, Warland JS, McBride RA, Wagner-Riddle C. Laboratory-scale measurements of N2O and CH4 emissions from hybrid poplars (Populus deltoides x Populus nigra) Waste Manag. Res. 2004;22:454–465. doi: 10.1177/0734242X04048832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Díaz-Pinés E, et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from stems of ash (Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Plant Soil. 2015;398:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2629-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevanto S, et al. Wintertime photosynthesis and water uptake in a boreal forest. Tree Physiol. 2006;26:749–757. doi: 10.1093/treephys/26.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolari P, et al. CO2 exchange and component CO2 fluxes of a boreal Scots pine forest. Boreal Environ. Res. 2009;14:761–783. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang C, Janzen HH, Cho CM, Nakonechny EM. Nitrous oxide emission through plants. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1998;62:35–38. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1998.03615995006200010005x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goshima N, et al. Emission of nitrous oxide (N2O) from transgenic tobacco expressing antisense NiR mRNA. Plant J. 1999;19:75–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakata M, Takahashi M, Zumft W, Sakamoto A, Morikawa H. Conversion of the nitrate nitrogen and nitrogen dioxide to nitrous oxides in plants. Acta Biotechnol. 2003;23:249–257. doi: 10.1002/abio.200390032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert KR, Bruhn A, Ambus P. Nitrous oxide emission from Ulva lactuca incubated in batch cultures is stimulated by nitrite, nitrate and light. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2013;448:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenhart K, et al. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from cryptogamic covers. Glob. Change Biol. 2015;21:3889–3900. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenhart K, et al. Nitrous oxide effluxes from plants as a potentially important source to the atmosphere. New Phytol. 2019;221:1398–1408. doi: 10.1111/nph.15455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu KW, Wang ZP, Chen GX. Nitrous oxide and methane transport through rice plants. Biol. Fert. Soils. 1997;24:341–343. doi: 10.1007/s003740050254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson EA, Keller M, Erickson HE, Verchot LV, Veldkamp E. Testing a conceptual model of soil emissions of nitrous and nitric oxides. BioScience. 2000;50:667–680. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0667:TACMOS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papen, H. et al. in Tree Species Effects on Soils: Implications for Global Change (eds Binkley, D. & Menyailo, O.) 165–172 (NATO Science Series IV-Earth and Environmental Sciences, Springer Netherlands, 2005).

- 29.Menyailo OV, Hungate BA, Zech W. The effect of single tree species on soil microbial activities related to C and N cycling in the Siberian artificial afforestation experiment—tree species and soil microbial activities. Plant Soil. 2002;242:183–196. doi: 10.1023/A:1016245619357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menyailo, O. V. & Hungate, B. A. in Tree Species Effects on Soils: Implications for Global Change (eds Binkley, D. & Menyailo, O. V.) 293–305 (NATO Science Series, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 2005).

- 31.Menyailo OV, Hungate BA. Tree species and moisture effects on soil sources of N2O: Quantifying contributions from nitrification and denitrification with 18O isotopes. J. Geophys. Res. 2006;111:G02022. doi: 10.1029/2005JG000058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kieloaho AJ, et al. Stimulation of soil organic nitrogen pool: The effect of plant and soil organic matter degrading enzymes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016;96:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker TS, Bais HP, Grotewold E, Vivanco JM. Root exudation and rhizosphere biology. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:44–51. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.019661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colmer TD. Long-distance transport of gases in plants: a perspective on internal aeration and radial oxygen loss from roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:17–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00846.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wassmann R, Aulakh MS. The role of rice plants in regulating mechanisms of methane emissions. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2000;31:20–29. doi: 10.1007/s003740050619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prendergast-Miller MT, Baggs EM, Johnson D. Nitrous oxide production by the ectomycorrhizal fungi Paxillus involutus and Tylospora fibrillosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011;316:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okiobe ST, Augustin J, Mansour I, Veresoglou SD. Disentangling direct and indirect effects of mycorrhiza on nitrous oxide activity and denitrification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019;134:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bender SF, et al. Symbiotic relationships between soil fungi and plants reduce N2O emissions from soil. ISME J. 2014;8:1336–1345. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bender SF, Conen F, Van der Heijden MGA. Mycorrhizal effects on nutrient cycling, nutrient leaching and N2O production in experimental grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015;80:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruhn D, Albert KR, Mikkelsen TN, Ambus P. UV-induced N2O emission from plants. Atmos. Environ. 2014;99:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.09.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornley JHM. Plant growth and respiration re-visited: maintenance respiration defined—it is an emergent property of, not a separate process within, the system—and why the respiration: photosynthesis ratio is conservative. Ann. Bot. 2011;108:1365–1380. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lintunen A, et al. Bursts of CO2 released during freezing offer a new perspective on avoidance of winter embolism in trees. Ann. Bot. 2014;114:1711–1718. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans DE. Aerenchyma formation. New Phytol. 2003;161:35–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arbellay E, Stoffel M, Bollschweiler M. Wood anatomical analysis of Alnus incana and Betula pendula injured by a debris-flow event. Tree Physiol. 2010;30:1290–1298. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sorz J, Hietz P. Gas diffusion through wood: implications for oxygen supply. Trees. 2006;20:34–41. doi: 10.1007/s00468-005-0010-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapuis-Lardy L, Wrage N, Metay A, Chotte JL, Bernoux M. Soils, a sink for N2O? A review. Glob. Change Biol. 2007;13:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lendzian KJ. Survival strategies of plants during secondary growth: barrier properties of phellems and lenticels towards water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:2535–2546. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pihlatie M, et al. Gas concentration driven fluxes of nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide in boreal forest soil. Tellus. 2007;59B:458–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0889.2007.00278.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mäkisara, K., Katila, M., Peräsaari, J. & Tomppo, E. in Natural Resources and Bioeconomy Studies 10/2016 (Natural Resources Institute Finland, 2016).

- 50.Dobrovolny L. Density and spatial distribution of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) regeneration in Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karsten) stands in the central part of the Czech Republic. IForest-Biogeosciences Forestry. 2016;9:666–672. doi: 10.3832/ifor1581-008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ge ZM, et al. Impacts of changing climate on the productivity of Norway spruce dominant stands with a mixture of Scots pine and birch in relation to water availability in southern and northern Finland. Tree Physiol. 2011;31:323–338. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowatte S, et al. Emissions of nitrous oxide from the leaves of grasses. Plant Soil. 2014;374:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1879-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simpson IJ, Edwards GC, Thurtell GW. Micrometeorological measurements of methane and nitrous oxide exchange above a boreal aspen forest. J. Geophys. R. 1997;102:29331–29341. doi: 10.1029/97JD03181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eugster W, et al. Methodical study of nitrous oxide eddy covariance measurements using quantum cascade laser spectrometery over a Swiss forest. Biogeosciences. 2007;4:927–939. doi: 10.5194/bg-4-927-2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nicolini G, Castaldi S, Fratini G, Valentini R. A literature overview of micrometeorological CH4 and N2O flux measurements in terrestrial ecosystems. Atmos. Environ. 2013;81:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Högberg P, Näsholm T, Franklin O, Högberg MN. Tamm review: on the nature of the nitrogen limitation to plant growth in Fennoscandian boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017;403:161–185. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aber J, et al. Nitrogen saturation in temperate forest ecosystems—hypotheses revisited. Bioscience. 1998;48:921–934. doi: 10.2307/1313296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butterbach-Bahl K, Gasche R, Willibald G, Papen H. Exchange of N-gases at the Hoglwald Forest—a summary. Plant Soil. 2002;240:117–123. doi: 10.1023/A:1015825615309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kreutzer K, Butterbach-Bahl K, Rennenberg H, Papen H. The complete nitrogen cycle of an N-saturated spruce forest ecosystem. Plant Biol. 2009;11:643–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pirinen, P. et al. Tilastoja Suomen Ilmastosta 1981–2010 (Climatological Statistics of Finland 1981–2010) 1–96 (Finnish Meteorological Institute Reports 2012/1, Helsinki, 2012).

- 61.Maier M, Machacova K, Lang F, Svobodova K, Urban O. Combining soil and tree-stem flux measurements and soil gas profiles to understand CH4 pathways in Fagus sylvatica forests. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018;181:31–35. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201600405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pihlatie M, et al. Comparison of static chambers to measure CH4 emissions from soils. Agr. For. Meteorol. 2013;171–172:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pumpanen J, et al. Respiration in boreal forest soil as determined from carbon dioxide concentration profile. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2008;72:1187–1196. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2007.0199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ilvesniemi H, et al. Water balance of a boreal Scots pine forest. Boreal Environ. Res. 2010;15:375–396. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hari, P. et al. in Physical and Physiological Forest Ecology (eds Hari, P., Heliövaara, K. & Kulmala, L.) 471–487 (Springer Science, 2013).

- 66.Rannik Ü, Keronen P, Hari P, Vesala T. Estimation of forest–atmosphere CO2 exchange by eddy covariance and profile techniques. Agr. For. Meteorol. 2004;126:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2004.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mammarella I, et al. Relative humidity effect on the high-frequency attenuation of water vapor flux measured by a closed-path eddy covariance system. J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech. 2009;26:1856–1866. doi: 10.1175/2009JTECHA1179.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Machacova, K. et al. Summer fluxes of nitrous oxide from boreal forest. In Global Change: A Complex Challenge, Conference Proceedings, 78–81 (Global Change Research Center, Brno, 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.