Abstract

PURPOSE

In 2012, the French African Pediatric Oncology Group established the African School of Pediatric Oncology (EAOP), a training program supported by the Sanofi Espoir Foundation’s My Child Matters program. As part of the EAOP, the pediatric oncology training diploma is a 1-year intensive training program. We present this training and certification program as a model for subspecialty training for low- and middle-income countries.

METHODS

A 14-member committee of multidisciplinary experts finalized a curriculum patterned on the French model Diplôme Inter-Universitaire d’Oncologie Pédiatrique. The program trained per year 15 to 25 physician participants committed to returning to their home country to work at their parent institutions. Training included didactic lectures, both in person and online; an onsite practicum; and a research project. Evaluation included participant evaluation and feedback on the effectiveness and quality of training.

RESULTS

The first cohort began in October 2014, and by January 2019, 72 participants from three cohorts had been trained. Of the first 72 trainees from 19 French-speaking African countries, 55 (76%) graduated and returned to their countries of origin. Four new pediatric oncology units have been established in Niger, Benin, Central African Republic, and Gabon by the graduates. Sixty-six participants registered on the e-learning platform and continue their education through the EAOP Web site.

CONCLUSION

This training model rapidly increased the pool of qualified pediatric oncology professionals in French-speaking countries of Africa. It is feasible and scalable but requires sustained funding and ongoing mentoring of graduates to maximize its impact.

INTRODUCTION

According to a global report by the WHO, chronic diseases are responsible for > 60% of all deaths worldwide, with 80% of these deaths occurring in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In adults, cancer is the second leading cause of death but could be reduced by at least 40% if preventive measures were in place.1 Pediatric cancer is not preventable, but early correct diagnosis and high-quality treatment lead to 80% cure rates for children who develop cancer.2

A 2017 study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the International Association of Cancer Registries showed that the global occurrence of childhood cancer has increased by 13% since the 1980s, which indicates a rising need for improved pediatric oncology services.3 This trend will have profound effects in Africa because the African population today represents 16.4% of the world population (1.2 of 7.3 billion), is the fastest growing continent, and is estimated to reach 25% of the global population by 2050. In addition, 41% of Africans are < 15 years of age compared with 26% of people in the rest of the world.4

In 2019, Ward et al5 estimated that there were 397,000 incident cases of childhood cancer worldwide in 2015 of which only 224,000 were diagnosed. This finding suggests that 43% of childhood cancer cases were undiagnosed globally, with substantial variation by region that ranged from 3% in Western Europe and North America to 57% in western Africa. By taking into account population projections, Ward et al5 estimated that there will be 6.7 million cases of childhood cancer worldwide from 2015 to 2030.

To address the increasingly urgent and specific need for pediatric oncology in French-speaking African countries, a group of physicians and volunteers created the French African Pediatric Oncology Group (GFAOP) in 2000 led by Jean Lemerle, MD.6 The group aimed to improve health care quality and access in French-speaking African countries by establishing pilot units. The pilot units emphasized the need for pediatric oncology health care provider training because some clinicians who work in French-speaking African countries had not received such specialized or formal training.7 The proposed educational programs designed for western populations are costly and increase the risk of brain drain because salaries are higher and working conditions are better. Furthermore, the training program must be incorporated into a more comprehensive and efficient global pediatric oncology health care program.

In 2012, the GFAOP established the African School of Pediatric Oncology (EAOP). This project is supported primarily by the Sanofi Espoir Foundation as part of the My Child Matters program.8 Other supporters include the Lalla Salma Foundation for Cancer Prevention and Treatment, the Moroccan Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, the Gustave Roussy Institute’s School of Cancer, and the Moroccan parents association Avenir.

Initially, the EAOP began with offering intensive, unaccredited courses in pediatric oncology, but feedback from both directors and participants stated a need for more in-depth training and prompted the GFAOP to develop a formal pediatric oncology training program with the following objective: To provide physicians in French-speaking African countries with standardized pediatric oncology knowledge and skills to raise the level of competency in physicians working with children with cancer.9 This article describes the framework of the diploma program and reports the results of the first three cohorts.

METHODS

Training Committee

The first step in this process was the establishment of a training committee (TC). The EAOP TC included renowned faculty members with pediatric oncology experience in LMICs. The committee comprised 14 members with different backgrounds (10 pediatric oncologists, two radiation therapists, one pathologist, one pediatric surgeon) and nationalities (seven Moroccan, five French, two American).

The TC’s mission was to develop the training objectives and core curriculum for the Pediatric Oncology Diploma, evaluate and select the trainers, validate objectives and practical training sites, assist in the selection of program participants, approve research topics, and evaluate participants’ written examinations and research projects. The TC was supervised by the EAOP training program directors. The first TC task was to develop the pilot curriculum.

Curriculum Building

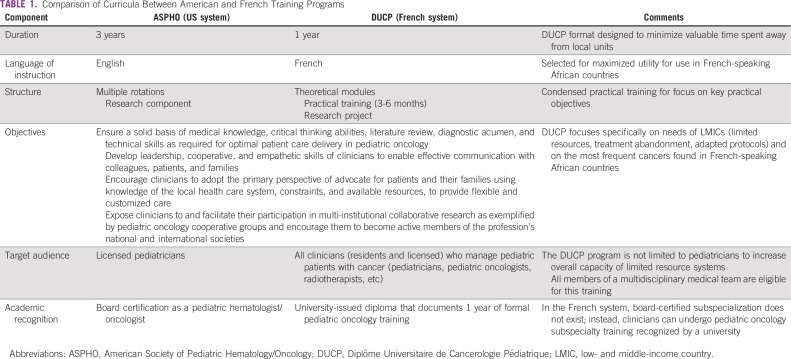

To select the most appropriate training model for French-speaking African countries, the EAOP began with comparing the French and American systems of specialized pediatric oncology training. Because participants were often the sole pediatric oncology practitioners in their regions, priority was given to a program that enabled participants to gain the most critical skills with the least amount of time spent away from their local positions. Thus, in accordance with the needs, resources, and limitations of clinicians in French-speaking African countries, the French model Diplôme Inter-Universitaire d’Oncologie Pédiatrique was selected.10 The curriculum objectives were also concordant with the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.11 Table 1 lists and compares curricula between American and French training programs. As a result of this process, the EAOP established in 2014 the first formal program of its kind in Africa: a 1-year diploma program in pediatric oncology known as the Diplôme Universitaire de Cancerologie Pédiatrique (DUCP). The program was delivered in French to ensure participants’ maximal comprehension.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Curricula Between American and French Training Programs

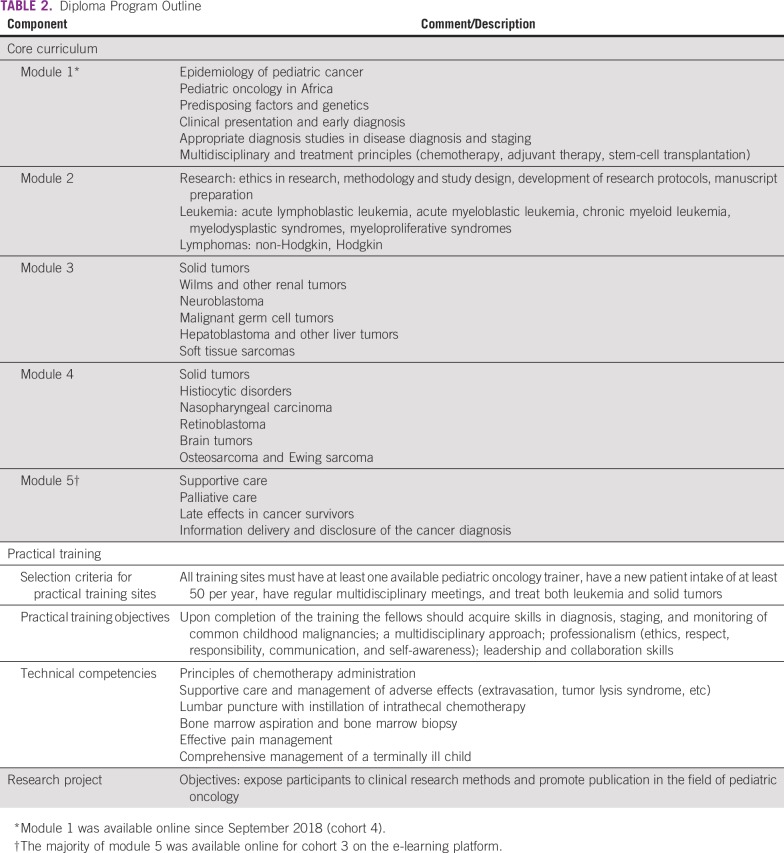

Table 2 lists an outline of the training program. After developing the training program, the TC began the process of curriculum recognition. The committee developed the program curriculum in compliance with the Mohammed V University and Paris-Sud University criteria for a diplôme universitaire program. The curriculum was submitted for recognition by the two universities as a formal training program in pediatric oncology.

TABLE 2.

Diploma Program Outline

Participant Selection

Upon a call for application through the GFAOP and the Moroccan national pediatric oncology network, the training program admitted 15 to 25 new fellows per year. The target audience included French-speaking African clinicians from various specialties in managing children with cancer (pediatric oncologists, pediatricians, radiation therapists, pediatric surgeons, etc). The applicants were required to provide a curriculum vitae, letter of intent, and letter of recommendation from their head of department. All participants had to express commitment to returning to their institutions to serve in pediatric oncology. Most of the selected participants (70%) received financial support from the GFAOP through the My Child Matters program, which covered transportation, lodging, university registration fees, and a per diem. Approximately 20% of selected participants were unable to join the program because of financial constraints. The total cost of each cohort is approximately 60,000 euros.

Development of e-Learning Component

In the second year of the program, the e-learning platform was developed to reduce the duration of required onsite learning and to enhance and supplement the independent learning component. All lectures were recorded separately for use specifically in the e-learning platform, which was implemented during cohort 3. The online training system was part of a systemic vision that mixed face-to-face and distance learning (so-called blended learning), which alternated face-to-face sessions organized in Rabat with distance learning through the e-learning platform.12

Development of Evaluation Tools

Evaluation of participants.

After didactic courses and clinical practical training, each participant had to pass an examination to demonstrate their knowledge base and clinical skills in pediatric oncology. The examination included one clinical case and three written questions related to specific cancers, supportive care, palliative medicine, and so forth. The 6-month practical training included evaluation for professional behavior and clinical competencies on the basis of a rubric that covered the practical training objectives (Table 2). The research project required a formal presentation and was evaluated on the relevance of the topic to daily practice, methods quality and accuracy, data collection and analysis, clarity of results, and insightful interpretation and discussion. Participants were offered mentorship in their research projects from the 24 trainers and practical training facilitators. Success in the training program depended on board approval that covered three main sections: theoretical knowledge, clinical practice/practical training, and research project evaluation.

Program feedback survey.

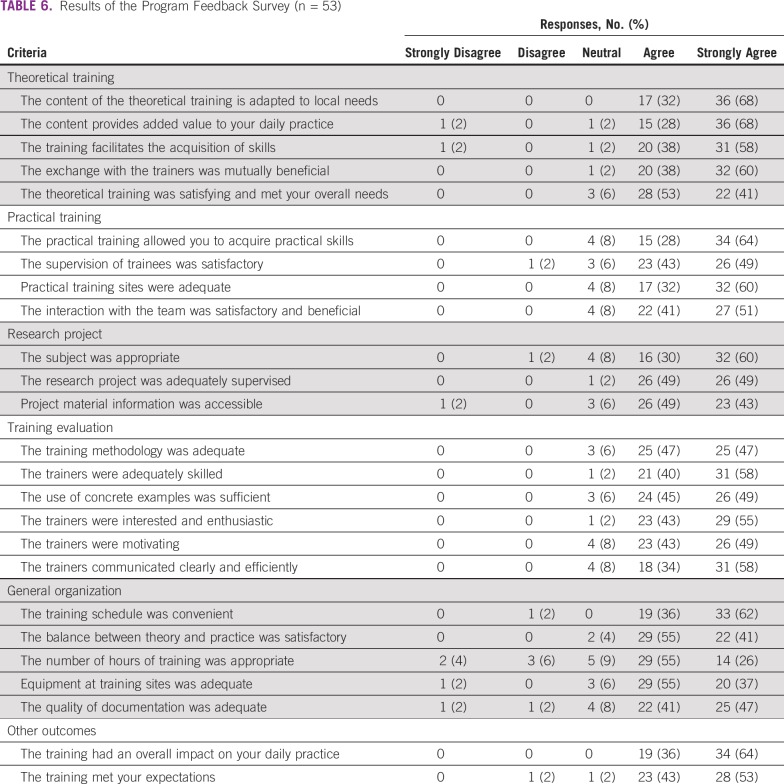

After completion of their training, all participants were asked to complete an anonymous feedback survey of 40 items (Table 6) on effectiveness and quality of training. Participants could respond using a 6-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Descriptive statistics were calculated as proportions of response options.

TABLE 6.

Results of the Program Feedback Survey (n = 53)

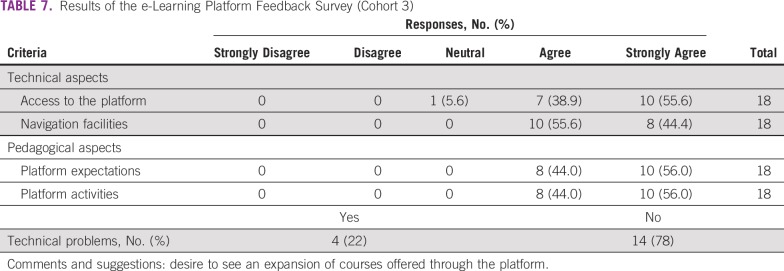

e-Learning feedback form.

After the launch of the e-learning curriculum in cohort 3, participants’ satisfaction was assessed using a short survey with five open-ended questions. The survey evaluated technical and pedagogical aspects of the platform.

RESULTS

The Pilot Curriculum

Outline of curriculum.

Table 2 lists an outline of the pediatric oncology diploma training program. The topics covered are similar to most pediatric oncology training programs available globally, but the content of the DUCP curriculum was specifically adapted to African LMICs by prioritizing the most curable diseases encountered in these countries, focusing on supportive care, and developing the multidisciplinary team. The curriculum emphasized the importance of using adapted protocols, such as GFAOP-adapted protocols,13,14 International Society of Paediatric Oncology Paediatric Oncology in Developing Countries protocols,15 and other published protocols with a proven record in LMICs.16 Other issues specific to pediatric oncology in LMICs, such as treatment abandonment, early diagnosis, and coping with limitations in resources, were also addressed.16,17

The duration of training was 12 months and comprised didactic lectures (120 hours given in five 3-day intensive sessions), 6 months of onsite practical training, and the completion of a research project that required a formal presentation at the end of the year. Research topics were selected on the basis of the recommendations of the TC with input from the participant. Each topic was required to have practical applications and to add value to the participant’s local or regional context. The practical training allowed the participants to acquire the competencies listed in Table 2. More than 24 trainers from different institutions were voluntarily involved in this program without compensation (transportation and lodging were covered by participant registration fees).

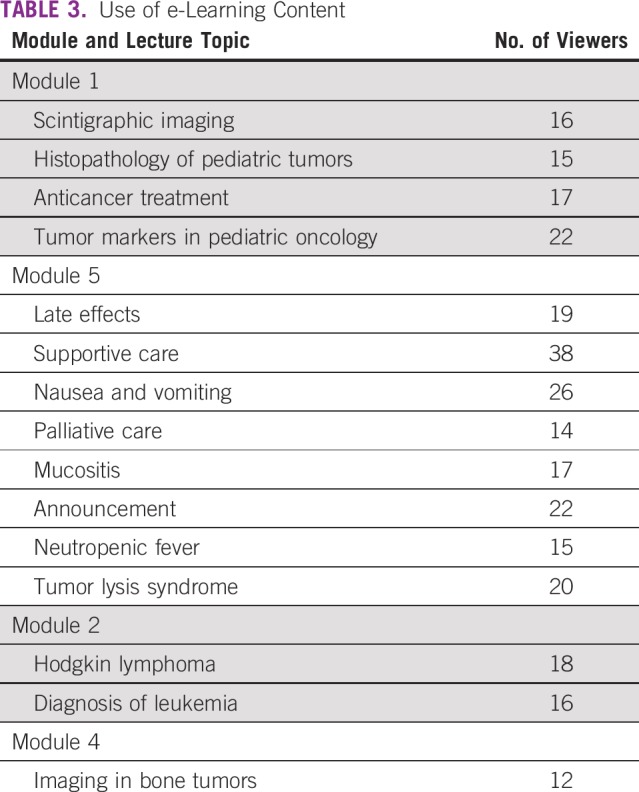

The e-learning component.

The e-learning platform12 includes recorded lectures for modules 1 through 5 that became available during the course of the program, with module 5 available as of September 2018 in time for use by cohort 3. Access was limited to program participants and to individually authorized persons. As of January 2019, the platform was accessed by 66 users: 10 trainers, 44 participants from cohort 2 and 3, three platform administrators, and nine visitors. The platform content included relevant literature (26 articles), one clinical case, and online lectures (Table 3). The total volume of courses recorded is 12 hours.

TABLE 3.

Use of e-Learning Content

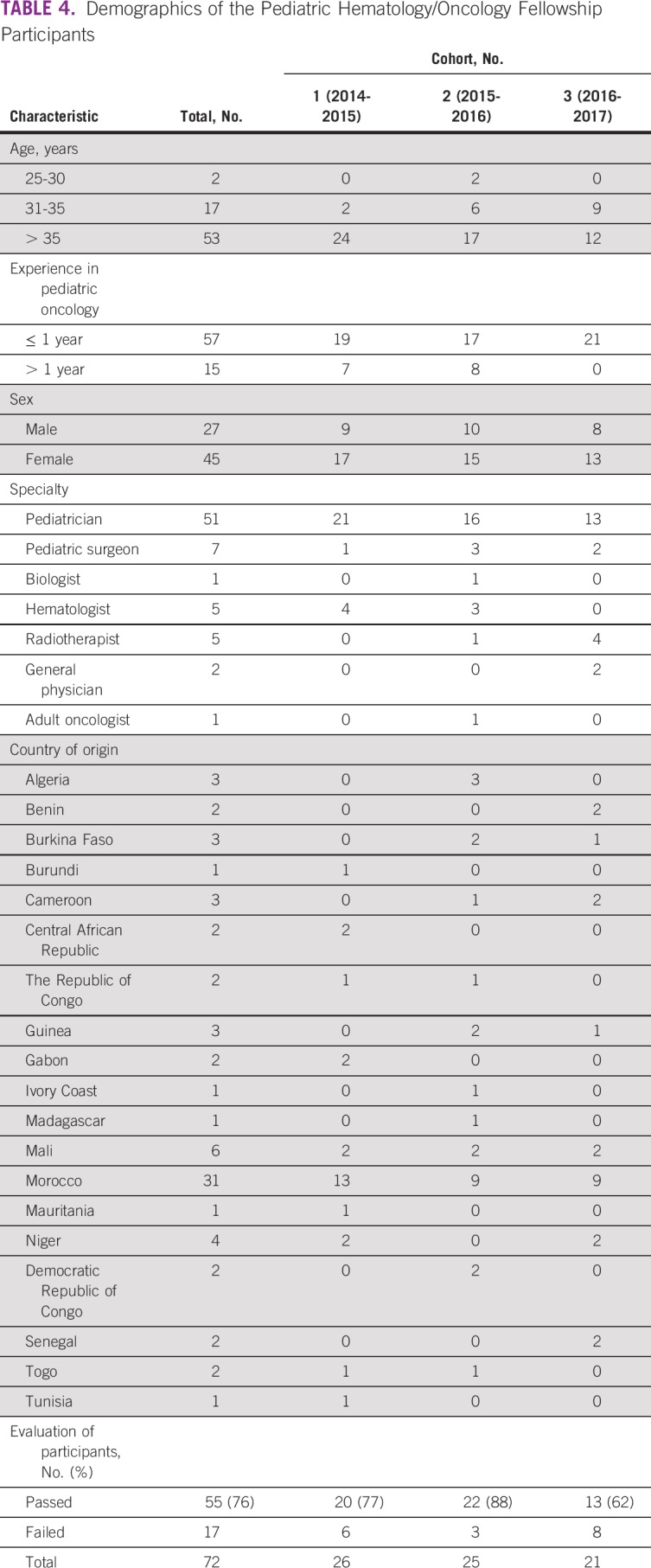

Demographics of Program Participants

Table 4 lists the demographics of program participants. From October 2014 to October 2017, we recruited 72 participants in three cohorts (26 in cohort 1, 25 in cohort 2, and 21 in cohort 3). The age of program participants decreased with each cohort, from 7.6% of participants age < 35 years in cohort 1 to 32% in cohort 2 and 43% in cohort 3. Cohorts 1 and 2 had a greater number of clinicians with previous pediatric oncology experience; all 21 participants in cohort 3 entered the program with no prior experience in pediatric oncology. Participants were from 19 French-speaking African countries and from a variety of specialties (mainly pediatrics, pediatric surgery, and radiotherapy; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Demographics of the Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Participants

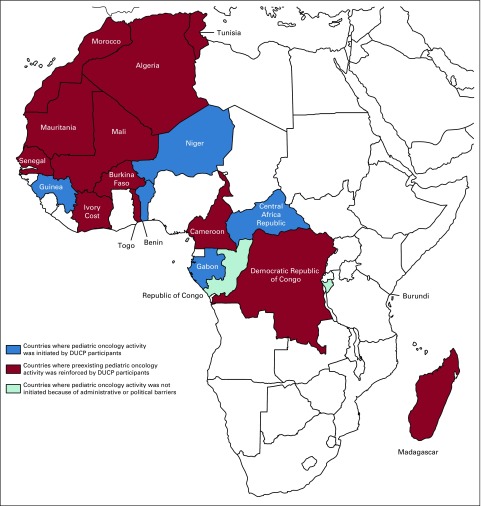

Upon completion of the DUCP program, the participants from Benin, Central African Republic, Gabon, and Niger were the first clinicians to begin practicing pediatric oncology in their countries. The diploma contributed to the administrative and peer recognition of participants as qualified physicians and promoted the initiation of pediatric oncologic activity in their respective countries with GFAOP support. Figure 1 shows the countries that were represented in the program and the pediatric oncology units created by DUCP participants.

FIG 1.

Map of Africa that shows the countries with participants in the Diplôme Universitaire de Cancerologie Pédiatrique (DUCP) program.

Evaluation

Participant evaluation.

Among the 72 participants in the DUCP program, 55 successfully completed the program; four withdrew from the program; and 13 did not complete one or more evaluations, including 11 who did not complete the research project largely because of administrative factors and, in one case, political instability. Among the participants who did not complete the research project, five were also unable to complete their practicum. One participant presented a final research project, but it was rejected by the review committee, and one participant did not pass the written examination.

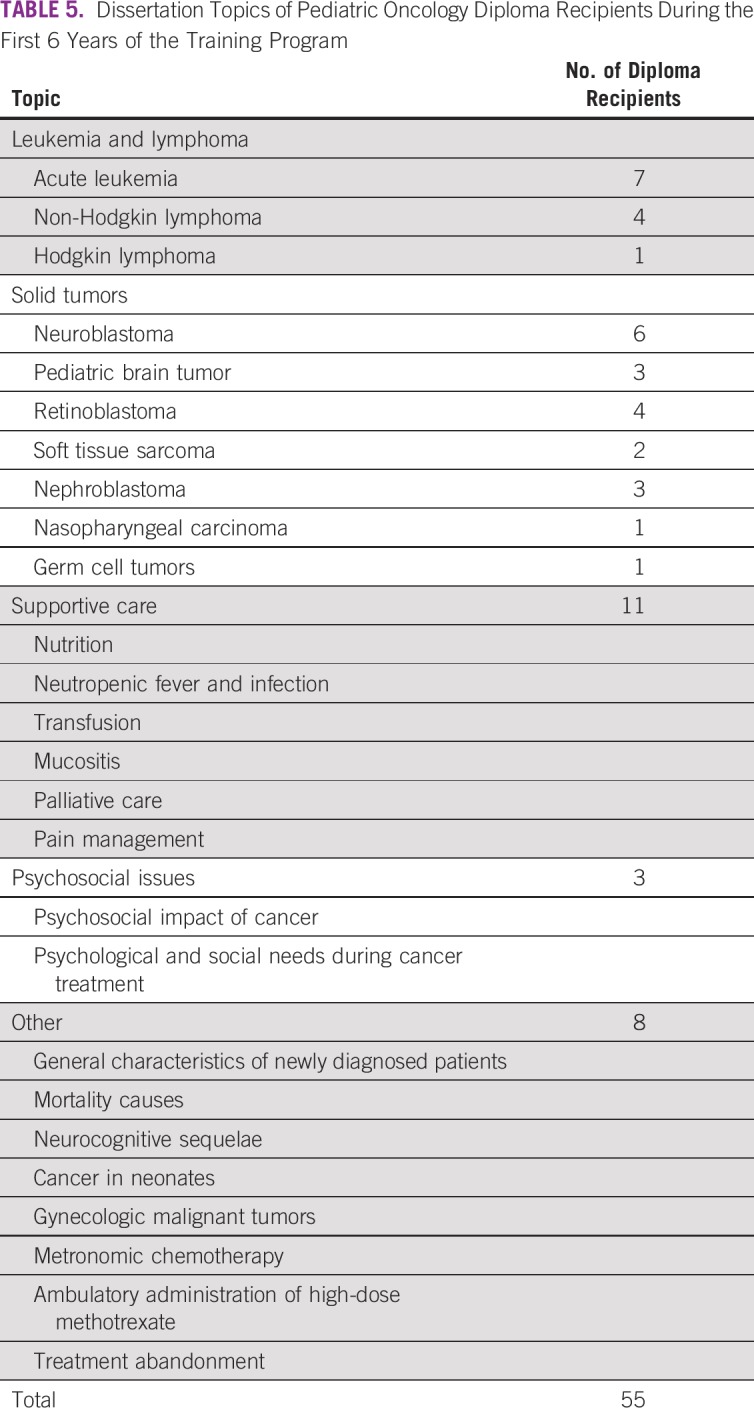

The selected topics for the clinical research projects primarily concerned the adaptation of pediatric oncology treatment to LMICs, the prevention of treatment abandonment, and international collaboration, consistent with issues important for pediatric oncology in LMICs. Clinical controlled trials were mainly evaluations of single-arm treatment protocols through clinical data collection, analysis of disease characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Table 5 lists the selected research topics.

TABLE 5.

Dissertation Topics of Pediatric Oncology Diploma Recipients During the First 6 Years of the Training Program

Projects were originally scheduled for completion within a 12-month period; the deadline was extended to 18 months to accommodate requests for extra time. Four projects were presented as posters and one as an oral presentation during International Society of Paediatric Oncology meetings.19-22 Two research articles are currently in the publication process.

The majority of the practical training was conducted in Moroccan general pediatric oncology units (54 participants) that met the practical training site criteria, with the exception of training for one participant in Tunisia and three in Algeria who were permitted to train in preapproved selected units. The 14 remaining participants (seven pediatric surgeons, five radiotherapists, one biologist, and one adult oncologist) trained in their respective specialties at locations that treat children with cancer, while regularly attending multidisciplinary meetings. Nine participants were unable to complete their practical training. Five pediatric surgeons completed a 6-month additional practicum in Europe (four in France, one in Belgium), and four pediatric oncologists completed a 2-month additional practicum in France.

Program feedback survey.

Fifty-three participants responded to the end-of-training survey. In general, the respondents were satisfied in all aspects of the program. The majority of respondents who included a written comment expressed a desire for additional time in the theoretical component as well as additional time and resources allocated to the research project. The final comments were related to challenges in the research project, such as inappropriate or unfeasible topic selection, lack of access to patient information needed for the project, and similar practical obstacles. Some clinicians not specialized in pediatric oncology (surgeons, radiotherapists) expressed a desire to have more-tailored theoretical training for their specialties (Table 6).

E-learning platform feedback (cohort 3).

Eighteen participants from cohort 3 responded to the e-learning platform survey (Table 7). Most agreed or strongly agreed to items related to technical and pedagogical aspects of the platform. Twenty-two percent of respondents reported technical problems related to Internet access and speed. Written comments included a desire to see an expansion of courses offered through the platform.

TABLE 7.

Results of the e-Learning Platform Feedback Survey (Cohort 3)

Success Stories

The two participants from the Central African Republic were the first clinicians to practice pediatric oncology in the country. One was referred to the program by a Central African Republic–based nongovernmental organization (the Bangui Childhood Cancer Association). The second, a political refugee who was in residency for pediatrics in Morocco, was recruited by the program and approved by the Bangui Hospital. The two trained together in cohort 1 and have both since returned to the Central African Republic and begun working together to create a pediatric oncology unit in Bangui, which has been accepted as part of the GFAOP network.

The clinic of an experienced Moroccan pediatric oncologist from cohort 1 has since been approved as a practical training site for the DUCP program. This graduate mentored five participants from cohorts 2 and 3. Of 55 participants who completed the program, 54 (98%) returned to their respective countries to develop local pediatric oncology programs.

DISCUSSION

In a region with limited infrastructure, resources, and quality training facilities, it was an impressive feat to coordinate the necessary funding, human resources, and academic framework to launch and execute a long-term academic program. Working together, we overcame many logistical challenges, such as coordinating partners from > 20 nationalities, more than five nongovernmental organizations, and two universities. Of note, the diploma is now considered a prerequisite for initiating any pediatric oncology activity in French-speaking African countries. An analogous program for Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa was established in 2016 in Uganda as part of the Global Hematology-Oncology Programs of Excellence program of Texas Children’s Hospital.23

The EAOP was able to recruit 72 participants from 19 African countries for the DUCP program. Before admission to the program, many participants were performing pediatric oncology tasks with limited, informal training that was largely on the basis of observational learning. After completion of the diploma program, many were able to reinforce their existing centers and, in some cases, establish satellite units outside the referral center. In the latest cohorts, the participants were younger than those of the first cohort, and none had prior pediatric oncology work experience. Eight participants from countries without previous pediatric oncology facilities were able to return and establish the first pediatric oncology units in their countries with support and ongoing mentoring from their GFAOP colleagues. Moreover, the multidisciplinary nature of the participants promoted a holistic approach to patient treatment and emphasized the value of nursing when developing pediatric cancer services.

Trained clinicians are referring new participants to the program on the basis of this success. Priority is given to those who are supported by their government and who have a secure position in their home country after their training to ensure the sustainability of the program.

The theoretical training was delivered in French, and the practical training component was shortened to maximize learning while minimizing the impact on the participants’ local facilities during the participants’ time away from home to receive the Morocco-based components of the training. The program included a research component to ensure that it furthered knowledge in the field and to develop analytical thinking skills needed for continuous quality improvement at the participants’ own pediatric cancer units.

Participants found the theoretical training to be too condensed and expressed a desire for less-compact sessions spread over 4 days instead of 3. In response, we developed an e-learning platform to reduce the intensity of the face-to-face sessions and to allow more class time for deeper discussion and case studies.

Overall, we experienced very few challenges during the practical training and received positive feedback from program participants and their mentors. Despite practical training in Morocco, the non-Moroccan participants were able to overcome language barriers with Arabic-speaking patients with limited French because of team integration and support from their many bilingual colleagues.

Participants were also required to select a topic and conduct a research project. We found that the participants were not adequately prepared to conduct academic research and complete the writing component. It became apparent that they required basic training and additional development in many specialized skills needed to successfully conduct research (ie, research methods, data management, statistical analysis, research ethics, writing skills, communication, professionalism).24-26 For participants who elected to conduct their research in Morocco, they experienced delays once they returned to their home countries because they found difficulties in accessing information and communicating with their Moroccan-based mentors. Participants who opted to conduct research in their home institutions faced delays as well because they could not begin their studies before the practical training component had been completed. These delays resulted in most participants finding themselves unable to complete their projects within the originally allocated 12 months. The program was unofficially extended to 18 months in the first three cohorts and has been officially extended for cohort 4 onward. Because of these factors plus the language barrier, as most pediatric oncology journals use English, only two participants have prepared their research projects for peer-reviewed publication. In addition, a need exists for more in-depth training on publication requirements.

The establishment of the e-learning platform has been another major success of the program because it has given EAOP the opportunity to use this tool to access existing resources. In following its commitment to the development of e-learning resources, the GFAOP recorded lectures for many years but did not have access to an online platform to host and share them. The establishment of the online platform represents EAOP’s first successful endeavor in the field of distance learning. The content of the platform has continued to expand and improve, and DUCP program participants have successfully accessed the materials during the home-based parts of the training.

The introduction of lectures through the e-learning platform has demonstrated the potential for increased use of this method and should be actively promoted in learning environments. Increased learner engagement in using the platform can be improved by sending regular notifications. Once the platform was established, we could focus on the quality of the recordings because professional recording allows participants to focus on the material. In addition, we hope to make the information available through a smart phone application in the future.

To address the lack of Internet access in some of the most remote pediatric oncology units, we are working to provide the e-learning content on compact disc. Use of the DUCP e-learning platform also benefits participants by teaching them how to navigate the Internet; find information from abroad using the available online resources; and use other e-learning platforms, such as St Jude’s Children Research Hospital’s Cure4Kids, which offers seminars in several languages, mainly English.27,28

A new community of pediatric oncologists has formed since the DUCP program participants connected during training. This group is anticipated to keep networking, sharing experiences, and working together in research programs both nationally and internationally.

The first challenge for the sustainability of the program is keeping the partners engaged and invested. Secondly, we need to continue to recruit relevant participants, even if pediatric oncology numbers are limited in Africa. We project that in the near future, our participant pool may diminish, and we may need to adjust the content to different specialties. Finally, we require continued access to funding, although continued program success will lead to better recognition and financial support.

In conclusion, we successfully created and implemented a dual-university accreditation program for pediatric oncology training in French-speaking African countries. Two thirds of participants completed the program, and 98% of them returned to their home countries to practice, including in Gabon, Central African Republic, Benin, and Niger, that had no pediatric oncology program before the DUCP program. We have built a community on social media that regularly shares updates to ensure follow-up. We have also designed a follow-up survey to evaluate participants’ experience of the program as well as their progress and development in the time since the training, which will be sent shortly. The e-learning French-language pediatric oncology platform remains as a durable educational asset for current and former program participants, and the program is ongoing with a fourth cohort having been recruited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to all the generous and committed partners who have voluntarily given their time and energy to this program. Trainers: Nazik Allali, Zaitouna El Hamany, Guy Leverger, François Doz, Odile Oberlin, Mohamed Khattab, Maria El Kababri, Abdellah Madani, Nicolas André, Hanane ElKacemi, Sanaa El Majjaoui, Mehdi Karkouri, Souha Sahraoui, Saadia Zafad, Soumia Zamiati, Mohamed Charif Chefchaouni, Abdessamad El Ouahabi, Samir Ahid, and Tarik El Madhi. GFAOP support group: Pierre Roger Machart, Benedicte De Charette, and Corinne Chalvon.

Footnotes

Presented at the 50th Annual Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, Kyoto, Japan, November 16-19, 2018.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Laila Hessissen, Catherine Patte, Carole Coze, Scott C. Howard, Amina Kili, Anne Gagnepain-Lacheteau, Mhamed Harif

Financial support: Anne Gagnepain-Lacheteau

Collection and assembly of data: Laila Hessissen

Data analysis and interpretation: Catherine Patte, Helene Martelli, Scott C. Howard, Amina Kili, Mhamed Harif

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jgo/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Scott C. Howard

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi, BTG, Amgen, Servier

Speakers’ Bureau: Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Servier

Anne Gagnepain-Lacheteau

Employment: Sanofi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Sanofi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO: Global status report on noncommunicable diseases, 2010. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf.

- 2.Lam CG, Howard SC, Bouffet E, et al. Science and health for all children with cancer. Science. 2019;363:1182–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Latest data show a global increase of 13% in childhood cancer incidence over two decades, 2017. https://www.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr251_E.pdf.

- 4. United Nations: World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, 2017. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html.

- 5.Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, et al. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: A simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:483–493. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groupe Franco-Africain d’Oncologie Pédatrique: GFAOP home page. http://www.gfaop.org.

- 7.Harif M, Traoré F, Hessissen L, et al. Challenges for paediatric oncology in Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:279–281. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard SC, Zaidi A, Cao X, et al. The My Child Matters programme: Effect of public-private partnerships on paediatric cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e252–e266. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hessissen L, Patte C, Leverger G, et al: The African School of Pediatric Oncology Initiative: Report from the French African Group of Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:292s, 2015 (abstr P212)

- 10. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2015.09.012. Vassal G, Landman-Parker J, Baruchel A, et al: Multidisciplinarity, education, and training in pediatric oncology-hematology [in French]. Arch Pediatr 22:1217-1222, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings C, Wechsler DS, Stine KC, et al. Consensus on a core curriculum in American training programs in pediatric hematology-oncology: A report from the ASPHO Training Committee. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24:503–512. doi: 10.1080/08880010701533645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groupe Franco-Africain d’Oncologie Pédiatrique: Diplôme Universitaire en Cancérologie Pediatrique e-learning platform. http://e-gfaop.org.

- 13.Traoré F, Sylla F, Togo B, et al. Treatment of retinoblastoma in sub-Saharan Africa: Experience of the paediatric oncology unit at Gabriel Toure Teaching Hospital and the Institute of African Tropical Ophthalmology, Bamako, Mali. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e27101. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harif M, Barsaoui S, Benchekroun S, et al. Treatment of B-cell lymphoma with LMB modified protocols in Africa--report of the French-African Pediatric Oncology Group (GFAOP) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1138–1142. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesseling P, Israels T, Harif M, et al. Practical recommendations for the management of children with endemic Burkitt lymphoma (BL) in a resource limited setting. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:357–362. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes FA, Thompson EI, Hustu HO, et al. The response of Ewing’s sarcoma to sequential cyclophosphamide and Adriamycin induction therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:45–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro RC, Steliarova-Foucher E, Magrath I, et al. Baseline status of paediatric oncology care in ten low-income or mid-income countries receiving My Child Matters support: A descriptive study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:721–729. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora RS, Eden T, Pizer B. The problem of treatment abandonment in children from developing countries with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:941–946. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benmiloud S, El Kababri M, Kili A, et al: Central nervous system relapse in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Experience of the Moroccan National Protocol (MARALL 2006). Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:101s, 2016 (abstr P0019)

- 20. El Kababri M, Ndakissa B, Kili A, et al: Mortality in a paediatric haematology oncology center (Rabat, Morocco). Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:278s, 2016 (abstr P0929) [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hessissen L, Khoubila N, Moudden L, et al: Pain management in Morocco: Report from The Moroccan Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:379s, 2015 (abstr 585)

- 22. Bouda C, Traore F, Atteby JJ, et al: A multicenter study for treatment of children with Burkitt lymphoma in sub Saharan paediatric units. A study of the “Groupe Franco Africain D’oncologie Pédiatrique” (GFAOP). Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:156s, 2015 (abstr O045)

- 23.Lubega J, Airewele G, Frugé E, et al. Capacity building: A novel pediatric hematology-oncology fellowship program in sub-Saharan Africa. Blood Adv. 2018;2:11–13. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018GS112742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denburg AE, Joffe S, Gupta S, et al. Pediatric oncology research in low income countries: Ethical concepts and challenges. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:492–497. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frugé E, Mahoney DH, Poplack DG, et al. Leadership: “They never taught me this in medical school.”. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:304–308. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181cf4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesselheim JC, Atlas M, Adams D, et al. Humanism and professionalism education for pediatric hematology-oncology fellows: A model for pediatric subspecialty training. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:335–340. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. St Jude’s Research Hospital: Cure4Kids home page. http://www.cure4kids.org.

- 28.Van Kirk Villalobos A, Quintana Y, Ribeiro RC. Cure4Kids for kids: School-based cancer education outreach. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;172:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]