Abstract

Background:

The cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) mutation, R222Q, neutralizes a positive charge in the domain I voltage sensor. Mutation carriers display very frequent ectopy and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).

Objectives:

To describe the effect of SCN5A R222Q on murine myocyte and Purkinje fiber electrophysiology, and identify underlying mechanisms.

Methods:

We generated mice carrying humanized wild-type (H) and mutant (RQ) SCN5A channels. We characterized whole heart and isolated ventricular and Purkinje myocyte properties.

Results:

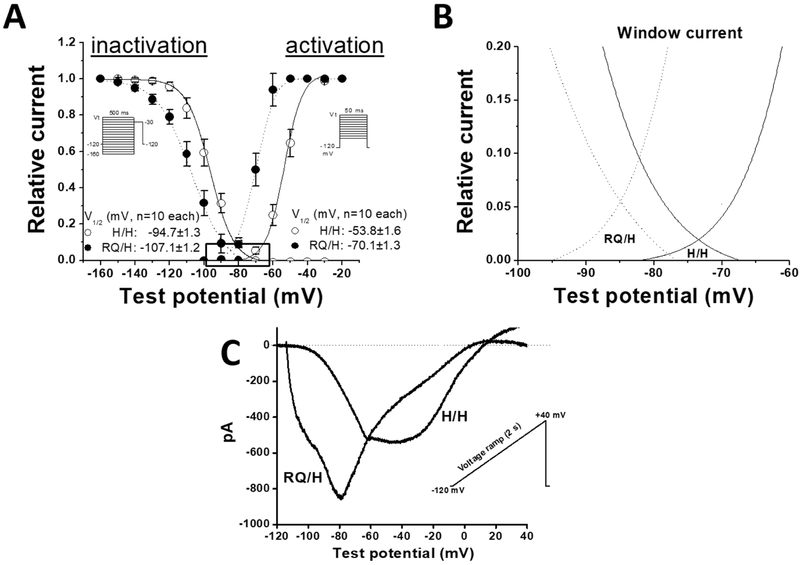

RQ/RQ mice were not viable. INa from RQ/H ventricular myocytes displayed increased “window current” and hyperpolarizing shifts in both inactivation and activation compared to H/H, as previously reported in heterologous expression systems. Surprisingly, action potentials were markedly abbreviated in RQ/H myocytes (APD90: 12.6±1.3 ms versus 29.1±1.0 ms in H/H, p<0.01, n=10 each). We identified a large. [K+]o-dependent outward gating pore current in RQ/H but not H/H myocytes, and decreasing [K+]o elicited EADs and triggered activity in isolated myocytes and ectopic beats in whole hearts. Further, RQ/H Purkinje cells displayed striking, consistent low voltage EADs. In vivo, however, RQ/H mice displayed little ectopy and contractile function was normal.

Conclusion:

While SCN5A R222Q increases plateau inward sodium current, action potentials were unexpectedly shortened likely reflecting an outward gating-pore current. Low extracellular potassium increased this pore current, and was arrhythmogenic in vitro and ex vivo.

Keywords: Dilated Cardiomyopathy, SCN5A, Channelopathy, Mouse models, sodium channels

Introduction

Variants in the pore-forming subunit of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 (encoded by SCN5A) cause diverse arrhythmia syndromes including Brugada and long QT syndromes, and rarely dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (1-5). Conduction slowing, atrial fibrillation, and frequent ventricular arrhythmia have all been implicated in SCN5A variants that cause DCM (1, 3, 4, 6, 7). The SCN5A mutation resulting in R222Q has been associated with frequent junctional or ventricular ectopic beats in six separate families and, in some cases, to DCM. Computational simulations and mapping in humans have suggested a Purkinje origin (8). Sodium channel blockers have been reported to suppress arrhythmias and improve left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (1, 8), although in one individual, LVEF was improved without any improvement in premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) (8).

In heterologous expression, R222Q (RQ) produces a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of the sodium channel, and an increase in window current in cells (1, 9, 10) which would be expected to increase action potential duration. In the present experiments, we found that in isolated mouse ventricular myocytes action potentials were markedly shortened and sensitive to low potassium in heterozygous mice compared to WT. Additionally, isolated RQ Purkinje cells displayed consistent early afterdepolarizations (EADs). INa in heterozygote isolated myocytes recapitulated the previously described gating behaviors, with the addition of an outward potassium-sensitive gating pore current.

Methods

Animal Model.

Using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange, we generated mice with the human SCN5A wild-type (H) or R222Q (RQ) alleles (11). For genotyping, a DNA fragment was first amplified with the primers 5’-GATTCTGGCTCGAGGCTTCTGC-3’ (forward) and 5’GAGGTGCCGTTCTTGAGCAGGT-3’ (reverse). Data were collected from both genders at 12 weeks (±3 days) or 6 months (±2 weeks). There was a significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in survivors of RQ/H x RQ/H matings (H/H 24; RQ/H 59; RQ/RQ 7; p=0.001), and RQ/RQ live birth pups died within the first week. Therefore, the results presented here compare H/H and RQ/H mice only. All studies using animals were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees at Vanderbilt University and were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (11), we generated mice with the human SCN5A wild-type (H) or R222Q (RQ) alleles. The transgenic mice are a knock in model as described previously (11). Briefly, Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange was used to replace the mouse SCN5A exon 2 with the full length human SCN5A cDNA. Since exon 2 contains the translational start site the mouse sodium channel is not expressed. All the mice we studied expressed human SCN5A on both alleles. For the heterozygous mice one allele was human WT and the other was the human sodium channel with the R222Q mutant. To generate RQ mice, we made a construct containing the human SCN5A cDNA with the RQ mutant and electroporated this construct into mouse stem cells containing the cassette acceptor site. Stem cells containing RQ were then selected for by antibiotic selection. RQ mutagenized stem cells were then injected into blastocysts to make chimeric mice. The chimeras were mated with mice devoid of any transgene. Pups from this mating were genotyped and those containing the RQ allele were bred with mice that were homozygous for the wild type human SCN5A gene.

Contactin-2-GFP mice generation.

In order to get 14 Purkinje cells, we crossed mice with humanized SCN5A, both WT and RQ, with contactin-2 mice from Glenn Fishman (12). Purkinje cells from SCN5A humanized WT (H) or heterozygous H/RQ, identifiable by green fluorescence, were then isolated for subsequent study.

Cardiomyocyte and Heart Isolation.

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation and euthanized by exsanguination. Each heart was excised and the ascending aorta was cannulated. For Langendorff perfusion experiments, hearts were exsanguinated and perfused with oxygenated Krebs buffer (in mmol/L; NaCl 119, NaHCO3 25, KH2PO4 1.2, MgCl2 1.0, CaCl2 1.8, glucose 10, Na-pyruvate 2.0. KCl was either 2.0 or 5.2 mM) through the aorta using gravity-flow retrograde-perfusion. HCl was used to adjust the solution pH to 7.4 and the perfusion temperature was kept at 37⁰C. Ventricular myocytes were isolated from 10 to 14 week-old mice by modifying a previously described collagenase/protease method (13). Briefly, hearts were perfused with collagenase (Worthington type II) and protease at 37°C then diced into small pieces and filtered through a 250 μm mesh. Cells were washed twice in a standard Tyrode solution containing 0.2 mmol/L of CaCl2 and resuspended in a solution containing 0.6 mmol/L of CaCl2. To isolate Purkinje cells, excised hearts were perfused with 1X perfusion buffer (mmol/L; NaCl 113, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 0.6, Na2HPO4 0.6, MgSO4-7H2O 1.2, NaHCO3 12, KHCO3 10, Taurine 30, HEPES buffer 10) for 4 minutes followed by digestion with 0.22mg/mL liberase (Roche) for 7-8 min at 37°C. Purkinje cells expressing a contactin2-GFP reporter (12) were isolated under a dissecting microscope. Cells were dissociated by pipetting gently in a perfusion buffer containing 10% FBS and 12 μM CaCl2 and strained through a 100mm cell strainer. The Purkinje cells were allowed to sediment for 8 minutes. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of PB containing 5% FBS and 12.5 μM CaCl2. 100mM of CaCl2 was added over 15 minutes to a final calcium concentration of 0.5mM. Cells were allowed to sediment for 8 minutes and resuspended in Minimum Essential Media (MEM) containing 0.6mM CaCl2.

Echocardiograms.

The Murine Cardiovascular Core at Vanderbilt University Medical Center recorded and analyzed transthoracic echocardiograms as previously described (14). Recordings were acquired by an individual blinded to the study conditions using a Vevo 2100 system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) with a 40-MHz transducer. Images were stored on cine loops for later blinded measurement. End-diastole and end-systole measurements were calculated in accordance with the leading-edge method of the American Society of Echocardiography (15). Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) and LV fractional shortening (FS) were automatically calculated by the Vevo 2100 standard measurement package. All measurements were performed and obtained in triplicate. Respiration peaks were excluded from the calculations.

Surface Electrocardiogram.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) leads I and II were recorded during light anesthesia using vapor titrated isoflurane as previously described (6). Following stabilization, ECG measurements were made manually using LabChart 7. For each parameter in an individual animal, three measurements at least 15 minutes apart were averaged. QRS duration was measured from the first deflection of the Q wave to the end of the S wave, which is the point of minimum voltage in the terminal phase of the QRS complex. QT interval was calculated from the beginning of the Q wave to the end of the T wave, defined as the point where the T wave merges with the isoelectric point. QTc was calculated from a formula developed for mice:

(16).

Voltage and Current Clamp.

Recordings of sodium and pore currents: Sodium current (INa) in mouse myocytes was recorded at room temperature. The external K+- and Ca2+-free NMDG solution contained (in mmol/L) NaCl 5, MgCl2 1.0, glucose 10, and HEPES 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The intracellular solution was (in mmol/L) NaCl 5, CsF 120, CaCl2 1.0, MgCl2 1.0, EGTA 10, TEA-Cl 10 and HEPES 10, pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. The overlapping potassium and chloride currents were eliminated by adding 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 500 μM) and 9-AC (30 μM), respectively. The gating pore current in cardiomyocytes was recorded with the same solutions, except for the addition of either 4 mM or 2 mM KCl to the external solution. Voltage clamp protocols are shown in Figures 1-3. In brief, peak sodium current (INa) was recorded using 50 ms pulses from the holding potential of −120 mV to +20 mV in 10 mV increments to generate the I-V curves of activation. Voltage dependence of inactivation was studied using 500 ms pre-pulses from −160 to −30 mV in 10 mV increments, followed by a 100 ms test pulse to −30 mV. The late sodium current (INa,L) was recorded with 200 ms pulsing from −120 mV to −30 mV and then measured at a time window of 195-198 ms before capacitance transient. The ramp/window current was recorded with a 2 sec slow ramp protocol from −120mV to +40 mV, which specifically examines the current without the need for a previously depolarizing pulse and allows the experiment to be conducted in a physiological extracellular sodium concentration of 135 mmol/L (17).

Figure 1: RQ/H mouse myocytes have larger peak cardiac sodium current (INa).

Raw current traces from A, H/H and B, RQ/H mouse ventricular myocytes (the voltage clamp protocol is shown as insert). C, I-V relations for INa activation in H/H and RQ/H. D, Ina inactivation time constants measured at variable test potentials. The insert shows two typical INa traces from H/H and RQ/H myocytes.

Figure 3: Gating Pore current present in RQ/H and action potential comparisons.

A, Lack of gating pore current in H/H myocytes. B, Gating pore current present in RQ/H myocytes. C, Ventricular AP traces recorded at a stimulation rate of 5 Hz in two H/H (in black) and RQ/H (in gray) myocytes. RQ/H myocytes show faster AP rising phase 0 and shorter AP duration. D, in silico AP comparisons with or without gating pore current using model described in Pandit et al. (18).

Action potential (AP) recordings.

In current-clamp mode, APs from isolated mouse ventricular myocytes and Purkinje cells were elicited by injection of a brief stimulus current (1-2 nA, 2-6 ms) at stimulation rates of 1 Hz and 0.1 Hz. For AP experiments, the bath (extracellular) solution was normal Tyrode’s, containing (in mmol/L): NaCl 135, KCl 4.0, CaCl2 1.8, and MgCl2 1.0, HEPES 5.0, glucose 10, with a pH of 7.4. The pipette-filling (intracellular) solution contained (in mmol/L): KCl 130, ATP-K2 5.0, MgCl2 1.0, CaCl2, 1.0, BAPTA 0.1 and HEPES 5.0, with a pH of 7.3 (adjusted by KOH). Ten successive AP traces elicited with a stimulation rate of 1 Hz were averaged for analysis of action potential durations at 90% repolarization (APD90). If needed, a slow stimulation rate of 0.1 Hz was also used for the experiments to observe potential arrhythmia-like action potentials. Data acquisition was carried out as previously described (17). Electrophysiological data were analyzed using pCLAMP version 9.2 software and the figures were prepared by using Origin 8.5.1 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Current-voltage relations for steady-state activation and inactivation were determined by fitting a Boltzmann function where I is the measured current, V is the applied voltage, Vh is the steady state V1/2 activation, and k is the slope factor, as previously described (17).

Action potentials in silico.

We used the myokit platform to model mouse action potentials from models generated by Pandit et al. (18). We adjusted the functional properties of INa to match those collected in RQ/H heterozygous ventricular myocytes and experimental I-V curves (Figure S1). K+ steady state efflux was adjusted to assess the dependence of pore current on resulting action potential phenotype, Ksteady state = 0.003 μS (normal) or 0.015 μS (with pore current).

Data analysis.

Results are represented as mean±SEM. For in vivo and ex vivo experiments, two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to compare groups. A p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Significance of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was calculated using a chi-square test (19).

Structural models of Nav1.5.

Homology model of Nav1.5 generated using American cockroach sodium channel NavPaS structure (20). Structure was visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics suite (Schrodinger, Portland, OR).

Results

H/RQ mice hearts have normal contractile function and only modest changes in ECG intervals.

In contrast to the human phenotype, heart rate, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVDD), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVSD), ejection fraction (EF), and fractional shortening (FS) were not different between the RQ/H and H/H genotypes (Figure S2). At six months, RQ/H mice had slightly shorter QRS, PR, and QTc intervals compared to H/H (Figure S2 and S3).

INa in RQ/H mouse myocytes recapitulates findings by heterologous expression.

Previous studies reported perturbed sodium channel function of SCN5A R222Q heterologously expressed in CHO cells (1, 9). In mouse ventricular myocytes, we recapitulate many of these functional defects: RQ/H myocytes had faster inactivation, negative shift in activation and inactivation, and increased “window” current at more negative potentials (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, RQ/H myocytes were slightly larger than H/H (larger cell capacitance 191.1± 8.2 pF RQ/H vs. 162.2±7.3 pF in H/H, n=10, p=0.017). The window current profile is similar to that observed previously (21). We do not observe positive currents during the ramp protocol, and we speculate that this represents the rapid inactivation of the (outward) gating pore current compared to the inward window current.

Figure 2: RQ/H affects sodium channel gating in mouse myocytes.

A, Current-voltage (I-V) relations for INa activation and inactivation in two groups of myocytes. B, Expanded from boxed crossover curve areas in panel A). C, Raw ramp current traces recorded with a ramp protocol under an external sodium concentration of 135 mM.

Shorter action potentials in RQ/H mice.

Unexpectedly, action potentials in RQ/H myocytes were strikingly shorter than that seen in H/H myocytes (Figure 3C): 12.6±1.3 ms (APD90, RQ/H) vs 29.1±1.0 ms (H/H, p<0.01, n=10 each). This result was unintuitive, given the apparent sodium current gain-of-function phenotype. Although the window current is increased in amplitude, it is also shifted to negative potentials (Figure 2), which would exert less influence on the AP until the late phase of repolarization (Figure 3D, dashed line).

ITO was unchanged in RQ/H and H/H and therefore not responsible for this outward cation current (Figure S4). Previous studies have reported charge-neutralizing mutations in the voltage sensor domain of the cardiac sodium channel can generate an outward cationic leak current, thought to permeate not through the canonical pore, but through a pathway adjacent to S4 termed a “gating pore” (22). As shown in Figure 3, gating pore current was readily recorded in RQ/H but not H/H myocytes. These data were acquired at an extracellular potassium ([K+]o) of 4mM, and in silico mouse action potential simulation reproduced this shorter action potential (Figure 3). Further, gating pore current was markedly increased with low [K+]o in RQ/H but not H/H myocytes (Figure 4). Lower [K+]o caused EADs and triggered activity (TA, Figure 5) in RQ/H but not H/H myocytes. In the cellular context, lower extracellular K+ induces prolonged action potentials due to a mechanism that ultimately results in increased late sodium current (23) (Figure 5F). In this context, the RQ/H cardiomyocyte exhibited a significant increase in arrhythmogenic features, most commonly triggered activity with afterdepolarizations (Figure S5), compared to H/H.

Figure 4: Low extracellular potassium increases pore gating current in RQ/H myocytes.

A, No pore gating current in H/H cells at 2 mM external potassium concentrations. B, Gating pore current in RQ/H cells at 2 mM external potassium concentrations. C, Summary of pore gating current I-V relations at 4 and 2 mM external potassium concentrations.

Figure 5: Low external potassium induced action potential abnormalities in H/H and R222Q (RQ/H) mouse ventricular cells.

A, In H/H myocytes, low external potassium (2 mM, or 2K) prolongs action potentials at 1 Hz. B, In RQ/H cells, low external potassium also caused action potential prolongation and increased triggered activity (indicated by small arrows) when the cells were being paced at 1 Hz. C-D, same as A-B but zoomed in to better observe action potential morphology. E, Percent ventricular ectopy in H/H (n=11) and RQ/H (n=11) isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts at 2 mM external potassium. F, Late sodium current increased by low external potassium in two groups of cells, equally for H/H and RQ/H.

Purkinje action potentials.

Purkinje fibers have been implicated in SCN5A R222Q carrier arrhythmogenesis (1, 8). In eight H/H Purkinje cells recorded, APs showed normal morphology without ectopic beats at 5 Hz, while in 4/6 of RQ/H Purkinje cells APs were short and variable with EADs arising at negative potentials, −60 mV (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of cardiac action potentials (APs) in H/H and RQ/H Purkinje cells.

A, APs recorded in H/H mouse cardiac Purkinje cell with normal rhythm. B, APs recorded in a RQ/H mouse cardiac Purkinje cell with low potential EADs. C, Superimposed APs from H/H and RQ/H Purkinje cells (shown from initial 15 ms of entire APs). D, Summary of APD50 and APD90 measured at 1 Hz in H/H and RQ/H Purkinje cells.

Rhythm abnormalities in RQ/H mice at low extracellular potassium.

No arrhythmias were observed with telemetry in 6-month-old awake-telemetered H/RQ and H/H mice. However, Langendorff-perfused hearts from H/RQ but not H/H mice exposed to low [K+]o (2 mM) did exhibit modest ventricular ectopy. Mean number of ectopic beats ± SEM for 11 cells each of RQ/H and H/H were 19% ± 8% and 0.5% ± 0.2% (p < 0.05), respectively.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to develop an in vivo model of the human SCN5A R222Q mutation to further probe the mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis in myocytes and Purkinje fibers. We showed that isolated RQ/H myocytes had a larger maximal INa conductance, hyperpolarizing shift in both activation and inactivation, and increased window current similar to previous reports in heterologous systems (1, 8). To our surprise, we found that RQ/H myocytes and Purkinje cells had shortened APD; RQ/H myocytes had a gating-pore current, a phenotype that augmented with lowered [K+]o; the in silico action potential reconstruction indicates this outward current can account for the action potential shortening. Despite these changes in sodium channel function assessed at the cellular level, R222Q mouse hearts had minimal manifestations in ECG parameters or junctional beats. However, there were several indications of SCN5A R222Q-induced dysfunction: 1) RQ/RQ mice did not survive past the first week of life (n = 7), 2) isolated RQ/H myocytes were larger than H/H cells, 3) in lower potassium RQ/H myocytes and Purkinje cells exhibited arrhythmogenic features, and 4) isolated RQ/H hearts exhibited ectopic beats in low external potassium.

RQ/H in cardiomyocytes at low extracellular potassium and in Purkinje cells displayed clear arrhythmogenic phenotypes. Given the most prominent features of RQ/H cells are the increase in sodium window current and the induced gating pore current, we speculate mechanisms resulting in the observed arrhythmogenic phenotypes are related to these channel electrophysiologic features. The Purkinje cell action potentials are especially interesting. Purkinje cells are more prone to EADs compared to cardiomyocytes (24), which may explain why we observe fewer late phase EADs in the cardiomyocyte context (Figure S5). In the Purkinje cell context, one possibility is that the increase in gating pore current increases the repolarization rate before Ca2+ stimulates an SR release. In this scenario, once the SR releases, the NCX reverses and stimulates a re-depolarization. (24, 25). Other channels could then be activated or otherwise contribute after SR release delays complete repolarization, possibly RQ SCN5A channels themselves, given the relatively low-voltage window current of the mutant channel (Figure 2).

DCM phenotype rarely segregates with individuals carrying SCN5A variants. Only four variants have been found in greater than five individuals that segregate with the DCM phenotype, R814W (4, 26, 27), D1275N (2, 4), T1247I (28), and M1245I (28). All of these variants are within the voltage sensors of the domains I-III, the domains responsible for channel opening (29), suggesting a possible common etiology (Figure 7). Moreau et al. suggest a cation pore current is the common modality and we recapitulate that current here (22). Additionally, Mathews et al. reported the voltage sensor charge neutralizing variant R222W in Nav1.4, the major voltagegated sodium channel present in skeletal muscle, causes hypokalemia induced periodic paralysis (30). However, this is not the sole generalizable mechanism since neither R814W and D1275N exhibit pore currents (6, 31). A gain in sodium current, like that reported here and for R814W, could produce the junctional beats observed clinically (1), however that would not explain the etiology of D1275N DCM, which we have reported results in disordered and very slow activation with obvious prolongation of QRS duration, possibly reflecting mislocalization of sodium channels within myocytes (6, 32). Taken as a whole, data accumulated to date indicate a heterogeneity in mechanisms that lead to SCN5A-linked DCM.

Figure 7: Nav1.5 protein molecule model with residues associated with DCM highlighted.

Homology model of Nav1.5 generated using American cockroach sodium channel NavPaS structure (20). Left, view from within membrane of SCN5A variants present in greater than five individuals and that segregate with the DCM phenotype, R814W (4, 26, 27), D1275N (2, 4), T1247I (28), and M1245I (28). Right, all variants fall within voltage-sensing modules I-III thought to be responsible for channel activation.

One additional surprising finding was the lack of any in vivo phenotype, despite these striking in vitro findings. One likely contributor is the very fast heart rate and/or high sympathetic tone in mice; clinical observation has noted that junctional beats increase during times of decreased heart rate (1, 8). Lower [K+]o elicited a modest phenotype ex vivo in isolated ventricular myocytes and would result in higher automaticity in Purkinje cells (33) and longer APD, the latter likely due to increase in late sodium current (Figure S5).

The totality of data in humans suggests frequent ectopy as the cause of DCM in the R222Q context (1-3). Our results support that hypothesis by reporting mice carrying SCN5A R222Q with infrequent ectopy and normal contractile function. We speculate that the rapid murine heart rate inhibited us from observing a more dramatic in vivo phenotype. Additionally, the presence of modulating common genetic variation, not investigated here, may also contribute to the overall observable phenotype. The channel electrophysiological data presented here are difficult to associate directly with the DCM phenotype consistently observed in heterozygous carriers of SCN5A R222Q; however, the consistency of aberrant cardiac sodium current, previously presented in heterologous expression systems and presented here in murine myocytes, suggests these electrophysiological defects are likely key contributors to the DCM phenotype.

Conclusions

In this study, we report isolated RQ/H mouse ventricular myocytes action potentials were shortened and sensitive to low potassium, isolated Purkinje cells had striking and regular early afterdepolarizations (EADs), and that both phenomena were influenced by the addition of a cation pore current. The lowering of extracellular potassium was found to be arrhythmogenic in vitro and ex vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Glen Fishman for providing contactin-2-GFP mice

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Bethesda, MD, USA, F32 HL137392 (LLD), K99 HL135442 (BMK), P50 GM115305 (DMR), and R01 HL118952 (DMR)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mann SA, Castro ML, Ohanian M, et al. R222Q SCN5A mutation is associated with reversible ventricular ectopy and dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:1566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNair WP, Sinagra G, Taylor MRG, et al. SCN5A mutations associate with arrhythmic dilated cardiomyopathy and commonly localize to the voltage-sensing mechanism. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:2160–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNair WP, Ku L, Taylor MRG, et al. SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation 2004;110:2163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson TM, Michels VV, Ballew JD, et al. Sodium channel mutations and susceptibility to heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2005;293:447–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershberger RE, Parks SB, Kushner JD, et al. Coding sequence mutations identified in MYH7, TNNT2, SCN5A, CSRP3, LBD3, and TCAP from 313 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2008;1:21–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe H, Yang T, Stroud DM, et al. Striking in vivo phenotype of a disease-associated human scn5a mutation producing minimal changes in vitro. Circulation 2011;124:1001–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezzina CR, Rook MB, Groenewegen WA, et al. Compound Heterozygosity for Mutations (W156X and R225W) in SCN5A Associated With Severe Cardiac Conduction Disturbances and Degenerative Changes in the Conduction System. Circ. Res. 2003;92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent G, Saal S, Amarouch MY, et al. Multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions: A new SCN5A-related cardiac channelopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:144–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair K, Pekhletski R, Harris L, et al. Escape capture bigeminy: Phenotypic marker of cardiac sodium channel voltage sensor mutation R222Q. Hear. Rhythm 2012;9:1681–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng J, Morales A, Siegfried JD, et al. SCN5A rare variants in familial dilated cardiomyopathy decrease peak sodium current depending on the common polymorphism H558R and common splice variant Q1077del. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2010;3:287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Hipkens S, Yang T, et al. Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange to rapidly and efficiently generate mice with human cardiac sodium channels. Genesis 2006;44:556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitra R, Morad M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:H1056–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rottman JN, Ni G, Brown M. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Ventricular Function in Mice. Echocardiography 2007;24:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation 1978;58:1072–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G. Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H747–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang T, Atack TC, Stroud DM, Zhang W, Hall L, Roden DM. Blocking Scn10a channels in heart reduces late sodium current and is antiarrhythmic. Circ. Res. 2012; 111:322–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit SV, Clark RB, Giles WR, Demir SS A mathematical model of action potential heterogeneity in adult rat left ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graffelman J Exploring Diallelic Genetic Markers: The HardyWeinberg Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen H, Zhou Q, Pan X, Li Z, Wu J, Yan N. Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science (80-. ). 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreau A, Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Delemotte L, Klein ML, Chahine M. Gating pore currents are defects in common with two Nav1.5 mutations in patients with mixed arrhythmias and dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015;145:93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau A, Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Chahine M. Biophysics, pathophysiology, and pharmacology of ion channel gating pores. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;5 April:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss JN, Qu Z, Shivkumar K. Electrophysiology of Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e004667 Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28314851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer V, Roman-Campos D, Sampson KJ, Kang G, Fishman GI, Kass RS. Purkinje Cells as Sources of Arrhythmias in Long QT Syndrome Type 3. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isenberg G, Borschke B, Rueckschloss U. Ca2+ transients of cardiomyocytes from senescent mice peak late and decay slowly. Cell Calcium 2003;34:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golbus JR, Puckelwartz MJ, Dellefave-Castillo L, et al. Targeted analysis of whole genome sequence data to diagnose genetic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TP, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, George AL. Divergent biophysical defects caused by mutant sodium channels in dilated cardiomyopathy with arrhythmia. Circ. Res. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priganc M, Zigova M, Boronova I, et al. Analysis of SCN5A Gene Variants in East Slovak Patients with Cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chanda B, Bezanilla F. Tracking Voltage-dependent Conformational Changes in Skeletal Muscle Sodium Channel during Activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews E, Labrum R, Sweeney MG, et al. Voltage sensor charge loss accounts for most cases of hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Neurology 2009;72:1544–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckermann TM, McLeod K, Murday V, Potet F, George AL. Novel SCN5A mutation in amiodarone-responsive multifocal ventricular ectopy-associated cardiomyopathy. Hear. Rhythm 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gui J, Wang T, Trump D, Zimmer T, Lei M. Mutation-specific effects of polymorphism H558R in SCN5A-related sick sinus syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gettes L, Surawicz B. Effects of low and high concentrations of potassium on the simultaneously recorded Purkinje and ventricular action potentials of the perfused pig moderator band. Circ. Res. 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.