Abstract

Background:

Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) may lead to an advanced stage of the disease and a poor prognosis. A psychoeducational intervention can be crucial in helping women with BC symptoms complete the examination procedures and reduce diagnosis delay of BC.

Objective:

To develop a psychoeducational intervention to reduce the delay of BC diagnosis among Indonesian women with BC symptoms.

Methods:

The development of the intervention included an inventory of crucial elements in developing psychoeducation through literature review as well as consultation with BC patients and healthcare providers. Additionally, we developed PERANTARA as the first pilot version of the self-help guided psychoeducational intervention. PERANTARA is an abbreviation for “Pengantar Perawatan Kesehatan Payadura”, which means an introduction to breast health treatment. The pilot feasibility study combined an expert review and a pilot testing in hospital settings. A semi-structured interview and the client satisfaction inventory were utilized to measure feasibility and acceptability of the intervention for Indonesian women with BC symptoms.

Results:

PERANTARA contained an oncologist’s explanation about BC and the BC survivors’ testimony to reduce the time to diagnosis. The pilot study results showed that most patients were satisfied with and trusted on PERANTARA.

Conclusion:

PERANTARA was feasible and acceptable for Indonesian patients with BC symptoms. The development framework suggested in this study can be applied to develop psychoeducational packages for other patients group, in particular, those interventional packages aimed at reducing diagnosis and treatment delays and non-adherence.

Keywords: Breast cancer, psychoeducation, time to diagnosis, oncology, Indonesia

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cause of cancer-related death among women, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Torre et al., 2015; Torre et al., 2016). In Indonesia, During the last decade, it has been shown that BC continues to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer and leading cause of cancer-related death among women, with an incidence rate of 40.3 and a mortality rate of 16.6 per 100,000 people (Ferlay et al., 2012). According to Dharmais Cancer Hospital (National Cancer Center in Indonesia), BC incidence and its mortality rate ranked top from 2010 to 2015 in comparison with any other types of cancer, and its prevalence is going to increase annually (Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia, 2016).

These reports on BC mortality rates are at odds with those in many high-income countries (HICs) since BC mortality rate has decreased in high-income countries probably due to increase of early BC symptoms awareness (both in healthcare providers and patients), early detection and diagnosis, and also increase of effective treatments availability (Denny et al., 2017). However, the prognosis for women with BC in LMICs is still poor because of the delays in diagnosis, treatment, or even both (Price et al., 2012; Unger-Saldana, 2014). The reasons for diagnosis and treatment delays are multifactorial (Freitas and Weller, 2015). There are patient-related factors such as lack of BC knowledge, belief in traditional treatment, and a negative attitude toward cancer diagnosis and/or treatment (Norsa’adah et al., 2011; Iskandarsyah et al., 2014a; Iskandarsyah et al., 2014b; Maghous et al., 2016). In addition, there are administrative problems as well as miscommunication between patients and health care providers that may hinder the process of scheduling and obtaining the diagnostic tests (Caplan, 2014; Unger-Saldana, 2014; Freitas and Weller, 2015).

Time to diagnosis, the interval time between the first clinical consultation and the time that BC is diagnosed and confirmed by the doctor, is critical in BC management (Caplan et al., 1996; Barber et al., 2004; Redaniel et al., 2015; Abu-Helalah et al., 2016). In Indonesia, about 60-70% women with BC appear to be already in an advanced stage (stage III-IV) when starting their treatments (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia, 2016). Furthermore, there is a fact that around 67% of women with BC symptoms who visit a hospital to consult for their breast abnormalities, tend to not continue with a thorough examination to obtain a definitive diagnosis (Sander, 2011). Therefore, promoting breast cancer awareness and adequate medical help-seeking behavior is essential for women at risk of BC to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment process and to achieve better prognosis (Khan et al., 2015; Denny et al., 2017).

A qualitative study on 50 Indonesian women with BC found that delay in seeking help and non-adherence to treatment were associated with lack of awareness and knowledge, patient’s perception about cancer as a dangerous deadly disease, believing cancer is incurable, emotional burden, unmet information needs, and trust in traditional healers. One of the crucial findings signified that most women described BC as a deadly and incurable disease, trusting on information obtained from stories and BC experiences of their relatives and neighbors, or mass media sources (e.g., magazines, newspapers, and television) (Iskandarsyah et al., 2014a; Iskandarsyah et al., 2014b; Azhar et al., 2016). Consequently, interventions to reduce time to diagnosis are needed to encourage women with BC symptoms to receive medical treatment immediately to achieve a better prognosis.

A cross-sectional study on 70 women with BC in Indonesia discovered that many of patients (41-86%) were not satisfied with the amount of written information about BC that they received (Iskandarsyah et al., 2013). Therefore, the use of concise and understandable educational materials (e.g., leaflets, posters, flipcharts table, and visualized storytelling) may complement the verbal explanations usually provided by the health care providers at clinics. Furthermore, the implementation of educational materials may be an appropriate solution in overcoming the lack of resources (e.g., experts, time, and finance).

To the best of our knowledge, evidence-based guided self-help psychoeducational interventions to reduce time to diagnosis are still lacking in Indonesia. Therefore, we developed PERANTARA, a self-help psychoeducational program, aiming at reducing the time to diagnosis. In the current study, we described the development of PERANTARA. we also reported a pilot study on its feasibility and acceptability for women with BC symptoms residing in Indonesia .

Materials and Methods

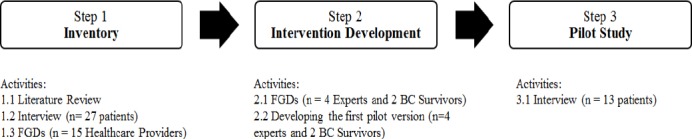

The development of PERANTARA consisted of three steps: 1) Inventory, 2) Intervention development, and 3) Pilot study See Figure 1, p 257.

Figure 1.

Intervention Development Framework

Inventory

A narrative literature review was conducted as an inventory step to ensure psychoeducation as a potential psychosocial intervention option for helping women with BC-related complaints, identify crucial elements for the intervention development, and to discover important issues or psychoeducation needs for women with BC symptoms. A narrative literature review is used to provide a comprehensive background to understand the current knowledge and highlight the importance of the new research (Cronin et al., 2008).

Furthermore, we conducted semi-structured interviews with women with BC (n= 27) and Focus Group Discussion (FGDs) with oncologists (n=5) and nurses (n=15) in the Hasan Sadikin Hospital Bandung. The patients’ age ranged from 30 to 69 years old. Fifteen (56%) patients had completed elementary school or had lower level of education. Nineteen (70%) patients were housewives or unemployed. Twenty-five (93%) patients were married, and the remaining two patients were widows. Twenty-six (96%) patients had health insurance provided by the government for people with low income, which was less than 2 million rupiahs a month. Both the interviews and FGDs addressed the following questions: (1) What would be a feasible way to tackle the reported diagnostic delay and adherence barriers? (2) Who should, can, and would you like to be involved in developing and implementing the interventions? (3) For which populations is it necessary to develop an intervention program?, and (4) What is a possible format of the intervention?

Intervention development

For developing PERANTARA, we involved experts from the field of health psychology, health communication, oncology, and audiovisual design. Three BC survivors were engaged in providing suggestions for the content, format, and utilization of the intervention packages. The intervention development comprised of the following two main activities:

1) Conducting FGD

FGDs with an oncologist, a health communication expert, two health psychology experts, and two BC survivors were held to review the intervention framework. The FGDs focused on the following issues: (1) The target population; (2) The person who delivers the contents; (3) The contents of the psychoeducation; (4) The delivery method; and (5) The delivery location.

2) Developing PERANTARA

One of the authors (HS) organized a series of collaborative work to develop the first pilot version of the psychoeducation package. The process started by writing a script as a guide to develop PERANTARA. After that, he collaborated with the audiovisual communication designers to prepare the printed material. The procedure included illustration drawing, layout making, lettering, and printing. In addition, he also cooperated with the audiovisual communication designer to develop the audiovisual storytelling. The process itself entailed video shooting, voice overtaking, music composing, animating motion graphic, and burning the DVD.

Pilot study

Participant

PERANTARA was pilot-tested on 13 patients to evaluate its feasibility for delivering in a controlled trial (Setyowibowo et al., 2017) and to gather preliminary information on its acceptability by patients. We recruited participants from Klinik Padjadjaran in Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia. The patients’ age ranged from 18 to 61 years old. Eight (62%) patients were women with BC symptoms, and five (38%) patients were women with BC. Five (38%) patients had completed elementary school, six (42%) patients had completed high school, and two (15%) had completed college level. Eight (62%) patients were housewives or unemployed. Nine (69%) patients had income less than 2 million rupiahs a month. Eight (57%) patients had health insurance provided by the government for people with low income. One patient refused to fill out a questionnaire after providing with the package of interventions because she underwent BC treatment one day before data collection and felt tired to continue the study.

Procedure

Eligible patients were invited to the hospital, informed about the details of the study, and oral and written informed consent was obtained from each of them. Patients who agreed to participate filled out the socio-demographic and medical history form, read and watched the intervention package, filled out the questionnaire , and responsed to the interview questions. This study was reviewed and approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital Bandung (RSHS) on December 23rd, 2013 (Document No: LB.04.01/A05/EC/127/XII/2013).

Instruments

A standard socio-demographic form was distributed to collect patients’ background data on ethnicity, age, marital status, religion, education level, employment status, income level, medical status, and insurance status. To assess feasibility and acceptability, we used the modified version of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ)-8 to fit the context of the use of the psychoeducation intervention (PERANTARA) in Indonesia. The original CSQ-8 has eight questions assessing the global client’s satisfaction in a clinical setting (Larsen et al., 1979; Matsubara et al., 2013). The patients respond to those items using a 4-point Likert scale, and the total scores range from 8 to 32. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. We applied the forward- and back-translation method to modify the CSQ-8. First, we translated the questionnaire from English to Indonesian, and then we translated it back into English. Afterward, we compared the original English version and the back-translation of the questionnaire to identify any discrepancies. After discussing any possible discrepancies, we achieved consensus and finalized the Indonesian version of the CSQ-8 that fitted the context of the use of PERANTARA. In this current study, the modified CSQ-8 achieved an acceptable reliability coefficient (α=.80).

We conducted open-ended interviews to obtain patients’ feedbacks on the intervention packages. The interviewer addressed the following questions: (1) How do you feel about this intervention package? (2) What is your opinion about the testimonies/stories conveyed by the survivors and the explanations conveyed by the doctors in this intervention package? (3) What is your opinion about the presentation of this intervention package (fonts, language, and image)?.

Data-analysis

The data from were analyzed qualitatively based on the Theoretical Thematic Analysis, a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). To analyze the qualitative data, we used a qualitative software program (NVIVO version 11.40). We first transcribed the interviews and FGDs. Two authors (HS and AI) created a coding directory independently (created nodes in NVIVO). After that, the nodes were compiled into main themes and presented in a coding matrix. The coding matrix was discussed until an agreement on the framework was achieved. Then, the verbatim material was coded and analyzed independently. Discussion meetings were organized to compare analyses, adapt the coding matrix and main themes, and analyze the data again before an agreement was met. Frequencies and percentages of participants mentioning a theme were calculated, and typical citations were noted. Descriptive statistics were used to describe participants and to summaries feedback on the intervention (using percentage).

Results

Inventory

As shown in Table 1, we retrieved 13 papers reporting research on psychoeducational interventions for a population that had psycho-social problems related to BC. In the papers we reviewed, the interventions were targeted at women with BC instead of focusing on women who were still uncertain about whether they had BC or not. Several methods to deliver psychoeducational programs were applied, both the self-help using psychoeducational material (written materials, audiovisual materials) as well as group delivery of psychoeducation. The psychoeducational programs were meant to increase knowledge on BC, increase satisfaction with information of BC and the treatment, reduce cancer worry, increase quality of life in women affected by BC, increase risk perception, and improve adjustment to BC diagnosis. According to findings of these studies, psychoeducation can be a potential psychosocial intervention option to help women with BC-related complaints. In addition, printed material and audiovisual materials can be the alternative delivery methods, especially when resources to deliver individual or group psychoeducation are limited (money, facilities, experts).

Table 1.

Overview of Studies Examining Educational Interventions in Women with BC Symptoms

| No | Study | Participants | Location | Interventions | Design | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fukui, et al. 2000 | BC patients (N=46) | Japan | Intervention Group: Facilitator-assisted (Group psycho-education, 1.5 hours weekly for 6 weeks) Control Group: the wait-list, no contact with the therapists until the intervention began. |

RCT | The Profile of Mood States (POMS) The Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MAC) scale The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

In the group psychoeducation group: significant reductions in of POMS total mood disturbance scores (p=.003), and increases in the POMS vigor scores (p=.002) and MAC fighting spirit scores (p=.003) post-intervention. No other differences between groups. |

| 2 | Jahraus, et al. 2002 | BC patients (N=79) | Canada | 1. Intervention Group: Self-help (Interactive video) 2. Control group: Facilitator-assisted (Individual and Group) |

Pre-Posttest, no control group | The Toronto Informational Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (TINQ-BC) Information-seeking activities: The Informational Styles Questionnaire (ISQ) |

The patient education program significantly increased the perceived knowledge adequacy scores: disease subscale (p = <.01), investigative subscale (p=<.01), treatments subscale (p = <.01), physical functioning (p = .01), psychosocial functioning (p = .01). No other differences between groups. |

| 3 | Appleton, et al. 2004 | Women who had received BC genetic risk counselling (N=163) | United Kingdom | Intervention Groups: Group 1: Scientific and psychosocial written self-help information related to familial risk of breast cancer Group 2: Scientific written self-help information related to familial risk of breast cancer 3. Control Group: standard care only |

RCT | Cancer Worry Scale (CWS) Objective knowledge of breast cancer risk-related topics Impact of Event Scale (IES) Perceived risk Perceived control |

There was a significant decrease in cancer worry ,i.e. a significant decrease in scores on the CWS from baseline to postintervention for Group 1 (z = 2.133, p =.033) and Group 3 (z = -2.449, p = .014). The total number of correct responses on the objective knowledge of BC significantly improved between baseline and postintervention for both Group 1 and Group 2 (z = -4.605, p =.000; z = -5.090, p = .000). |

| 4 | William, et al.2004 | BC patients (N=70) | United States | Intervention Group: Self-help (Audiotapes and written information) Control Group: Information about BC as usual |

RCT | The Self-care diary (SCD) The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Instrument (STAI) |

The self-help education intervention increased the use of recommended self-care behaviors for anxiety on the first SCD (p < .05). |

| 5 | Stanton, et al. 2005 | BC patients (N= 558) | United States | 1.Self-help standard written psychoeducation and peer-modeling videotape (VID) 2. Self-help standard written psychoeducation and peer-modeling videotape and two sessions with a trained cancer educator, and informational Workbook (EDU) 3. Self-help standard written psychoeducation Ccontrol) |

RCT | The four-item Short Form-36 (SF-36; subscales: Vitality, Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary. The Impact of Events Scale (IES-R) The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) Perceived Preparedness for Re-entry Scale |

VID produced significant improvement in Vitality subscale of SF-36 at 6 months relative to CTL (p = .018). No other differences between group. |

| 6 | Vallance, et.al. 2007 | BC Survivors (N=377) | Canada | Intervention group: Self-help 1. Print Material (PM) Group: written material. 2. Pedometer (PED) Group: Step Pedometer 3. Combination (COM) Group: written material and Step Pedometer CG: Standard recommendation to perform physical activities (PA), no additional intervention materials. |

RCT | The leisure score index (LSI) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) scale |

The BC specific materials and pedometer significantly improved the Quality of Life (p = .003). No other differences between group. |

| 7 | Burgess, et al. 2009 | Women at risk of developing BC (N=292) | United Kingdom | Core intervention: Self-help psychoeducation booklet) Boosted intervention: Self-help psychoeducation booklet followed by interview) |

Within-group before-and-after evaluation, no control group | Knowledge of BC symptoms, knowledge of risk, confidence to detect a change, and disclosure to someone close. The Lerman Breast Cancer Worry Scale |

At 1-month postintervention, both psychoeducational interventions increased the mean number of BC symptoms identified (p=.001) in the core intervention group (p=.001 and in the boosted intervention group (p=.001). No other differences between groups. |

| 8 | Capozzo, et al. 2010 | BC patients (N=29); | Italy | Facilitator-assisted (Group Psychoeducation) | Pre-Posttest, no control group | The Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale (Mini-MAC) | Reduction in anxious preoccupation subscale of Mini-MAC (p = .003). No significant changes on other subscales. |

| 9 | Dastan and Buzlu. 2012 | BC patients (N=76) | Turkey | Intervention groups: 1. Facilitator-assisted (Group psycho-education) 2. Self-help (Audiovisual information) Control group: usual care |

Pre-Post Test control group design |

The Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale (MACS) | At 6 months, group psychoeducation increased MACS subscales “fighting spirit,” (p = .000), and decreased “helplessness/hopelessness” (p = .000), “anxious preoccupation” (p = .000) and “fatalism” (p = 0.000). |

| 10 | Komatsu, et al. 2012 | BC patients (N= 82) | Japan | Intervention groups: 1.Self-help kit (written information and video) 2.Facilitator-assisted (Professional-led support groups) Control group: usual care |

Pre-Post Test control group design |

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Quality of Life (SF-36) |

Reduction in mental subscale score of SF-36 between the intervention and the control groups over the study period, but the effect size was small (F = 7

.48, p = .008, η2 = .004). No other differences between groups. |

| 11 | Sherman, et al. 2012 | BC patients (N = 249) | United States | Intervention groups: 1.Self-help (Videotapes); 2.Facilitator/Counselor assisted (Telephone Counseling) Control group: usual care |

RCT | The Profile of Adaptation to Life Clinical Scale (PAL-C) The Self-Report Health Scale (SRHS) The Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS) The Breast Cancer Treatment Response Inventory (BCTRI) |

Improvement within the telephone counselling group in PAL-C psychological well-being from baseline to adjuvant therapy, followed by a decrease from the adjuvant therapy phase to the ongoing recovery phase (p =.002). Higher side effect distress subscale of the BCTRI in intervention groups (p = .012) from post-surgery to ongoing recovery. No other differences between groups. |

| 12 | Jones, et al. 2013 | BC patients (N = 442) | Canada | Intervention group: Getting back on track (GBOT) Class Control group: Getting back on track (GBOT) Book. |

RCT, no inactive control | 1 The Knowledge Regarding Re-Entry Transition (a questionnaire specifically developed to cover the contents of GBOT curriculum) 2. The Perceived Preparedness for Re-Entry Scale (Stanton, et al. 2005) 3. The Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale 4. The Profile of Mood States Scale-Short Form (POMS-SF) 5. The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)-Health Distress Scale |

Group psychoeducational intervention significantly enhanced (p < .0001) the knowledge regarding the re-entry transition period and their feelings of preparedness for the re-entry phase (p < .0001). No other differences between groups. |

| 13 | Ram, et al. 2013 | BC patients (N = 34) | Malaysia | Facilitator assisted (Group psycho-education) | A cluster non-randomized trial | The WHO-five Well-being Index (1998 version) | The group psychoeducation improved the proportion of patients in the state of adequate well-being (p <.05) and reduced the proportion of depressed patients (p <.05). |

BC, Breast cancer; RCT, Randomize control trials

After consulting with women with BC and healthcare providers, we found seven themes, including (1) Target Population; (2) Content; (3) Delivery Method; (4) Delivery Agent; (5) Time Frame of Delivery; (6) Location; and (7) Possible barriers. The primary results per theme are described below.

1) Target population. Most of the BC patients (23 patients, 82.5%) recommended that the psychoeducational program should also be given to their caregivers (spouse, family, or their significant other). The healthcare providers (oncologists and nurses) also agreed that the psychoeducational program should be targeted at the caregivers too.

2) The content of the intervention. The patients stated that they needed to get more information from the experts regarding (a) breast cancer and it’s treatment (27 patients, 100%), (b) coping strategies and spirituality (25 patients, 92.6%), (c) nutrition and diet (16 patients, 59.3%), and (d) healthcare facilities and financial support (9 patients, 33,3%). The healthcare providers mentioned that patients needed to have sufficient understanding of their illness, so that these patients would immediately call for medical help and comply with the examination/diagnostic and treatment procedures.

3) Delivery method. Many participants (20 patients, 74.1%) believed that the delivery method should be interactive as well as informative using group discussion or individual consultation. Some of the patients (n= 14, 51.9%) suggested that psychoeducation materials, written and audiovisual, could be used as supplementary tools as long as they contained expert explanations and displayed visually attractive pictures but not too frightening ones. Several patients (n=7, 25.9%) suggested using the internet, even though they realized that some patients would need other people to help them in accessing the information on the internet.

4) Delivery agent (Facilitator). Both patients and healthcare providers agreed that healthcare provider should be delivery agents (facilitator). They mentioned that this might be a task of an oncologist (16 patients, 59.3%) and a nurse or a midwife (15 patients, 55.6%). Despite the fact that most of the patients understood that their oncologist or doctor had limited time to deliver the intervention, they still considered the oncologist as the key delivery agent.

5) The time frame of delivery. Both healthcare providers and patients recommended using this program when they were visiting the healthcare institution, at the first breast symptom before breast cancer diagnosis (19 patients, 70.4%), as well as during treatment (22 patients, 81.5%).

6) Location. Healthcare providers and some patients (14 patients, 51.9%) recommend nearby district hospitals as suitable locations for delivering psychoeducational programs.

7) Possible barriers. More than half of the patients (14 patients, 51,9%) considered their psychological conditions (anxiety, stress, fatigue) as potential barriers to engage in the intervention program. Some of the patients reported their financial problems (7 patients, 25.9%) and lack of communication facilities (3 patients, 11,1%) as potential obstacles against engaging in the intervention program. Approximately a quarter of the patients (8 patients, 29.6%) considered some characteristics of the care provider (communication skills, a limited amount of expert time and consultation) as possible challenges in the development and implementation of the intervention program. The care providers had a similar perspective toward these barriers. Moreover, they added that the educational / knowledge level of the patient was also important when developing and implementing an intervention program.

Intervention Development

The process of developing PERANTARA begins with FGDs involving an oncologist, health psychologists, a health communication expert, and BC survivors. The following were the results of the FGDs:

1) Who was the target population? The panel recommended patients as the target population of the psychoeducational intervention. Depending on the specific behavioral objective, interventions were delivered to the patient during her first visit to the hospital after finding BC symptoms, after BC diagnosis, or during treatment. Moreover, the caregiver was also considered to receive psychoeducation because the caregiver’s support would influence a patient’s health behavior.

2) Who should deliver the content? Potential psychoeducational intervention agents included oncologists, nurses, midwives, psychologists, social workers, or BC survivors. The oncologist was considered more credible due to his medical background, while the BC survivor was regarded more acceptable because of her experiences.

3) What were the contents? The psychoeducational program should provide both a simple scientific and medical explanation of BC symptoms and psychosocial support in order to stimulate the patients to immediately undergo the examination (diagnostic). This would enhance quick diagnose and treatment of the disease.

4) How to deliver the content? The selection of the delivery method was chosen according to demographic characteristics of the target population (middle-low education level, middle-low social, and economic status). Further, the limited availability of healthcare professionals and consultation time within the hospital was regarded. Therefore, the intervention was self-help, and support by practitioners was limited. Furthermore, the panel also recommended the use of attractive printed and audiovisual materials.

5) Where to deliver the program? Some locations were considered as potential places to deliver the psychoeducational package, including hospital, first line health services, and community activity center.

Based on these recommendations, the first author wrote a script (intervention blueprint) as guidance in developing an intervention package (PERANTARA). Critical elements in the intervention blueprint included title, format, language, target population, behavior objective, and main themes. (See Table 2. Intervention Blueprint). Based on this script, the PERANTARA package was developed with an audiovisual communication designer. The prototype was discussed with each of the research group members and, based on their feedback, the first pilot version of PERANTARA package was finalized.

Table 2.

Intervention Blueprint

| Title | Perantara: Pengantar Perawatan Kesehatan Payudara (Introduction To Breast Health Treatment) |

| Format | Table Flipchart |

| Language | Indonesia |

| Target Population | Female patients with breast cancer symptoms and newly diagnosed breast cancer. Demographic Status: middle to low level of education status, middle to low level of socio-economic status, live in the urban and rural area. |

| Behavior Objective | Reduce patient’s delay and improve patient’s adherence |

| Main Themes | |

| PERANTARA 1: Segera Periksa Ke Dokter (Immediately Consult The Doctor) |

Profile: Oncologist and Breast cancer survivor Early Detection and Breast Cancer Symptoms Risk Factor of Breast Cancer: Diet, Hormone and reproduction factor, Radiation exposure, Genetic factor, Women with history of breast cancer or non-cancerous breast lumps. Breast Examination Procedures: Physical examination, Biopsy, Breast imaging, Receptor test. Support to diminish treatment delay, seeking help from significant person, especially family and husband. |

| PERANTARA 2: Patuhi Rekomendasi Dokter (Comply Doctor’s Advice) |

Breast cancer treatment and its effects: Surgery, Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy, Hormone therapy. Patuhi Rekomendasi Dokter (Comply Doctor’s Advice) The choice of food, nutrition, and physical activity are recommended for breast cancer patients who are undergoing treatment. |

| Additional. | - Important list of address to gain support: informational, financial and emotional. - Personal notes: Complaints, questions asked, doctor’s advices and other important notes - Calendar, to write down the scheduling of examination and treatment process |

| Title | Kisah Nyata Dua Perempuan Tangguh |

| Format | Audiovisual Story Telling - DVD |

| Language | Indonesia |

| Target Population | Female patients with breast cancer symptoms and newly diagnosed breast cancer. Demographic Status: middle to low level of education status, middle to low level of socio-economic status, live in the urban and rural area. |

| Behavior Objective | Reduce patient’s delay and improve patient’s adherence |

| Scene (Key Message) | Description |

| Introduction | Introduction: Survivor’s Profile |

| Early Detection and Breast Cancer Symptoms | Breast Cancer Survivor’s Testimony: - Early Detection - Breast Cancer Symptoms |

| Support to reduce patient’s delay and increase adherence | Breast Cancer Survivor’s Testimony: - Support to dealing with bad news - Support to reduce patient’s delay - Support to increase adherence - Spirituality and Family Support |

PERANTARA is abbreviation for PENGANTAR PERAWATAN KESEHATAN PAYUDARA, which means introduction to breast health treatment. The word PERANTARA is in Indonesian language that means mediator or facilitator. The PERANTARA will be delivered using printable and audiovisual materials. These materials will be given to the patient at hospital.

Pilot Study

Qualitative Analysis

As demonstrated in Table 3 (Patient’s Opinion), patients stated that PERANTARA package was valuable and motivated them to undergo the medical procedure. Patients believed that the explanation given by the oncologist in PERANTARA was understandable and helpful. Furthermore, the patients stated that the narrative approach in presenting the information and utilization of a variety of images made PERANTARA clear and attractive

Table 3.

Patients’ Opinion

| Theme | Sub Theme |

|---|---|

| Usability How do you feel after using the PERANTARA? |

Helpful. Patients feel that PERANTARA is helpful because: improve their knowledge and awareness to continue the examination so that his complaint is promptly diagnosed and treated, and reduces anxiety and doubts to continue the examination and treatment. Patients feel that this intervention package is useful so they will recommend this package to others. Motivating. Patients feel motivated to use this package because it is attractive. Also, they also feel motivated to continue the examination and treatment after getting an explanation from the doctor and testimony from survivors in this package. |

| Source of Information What is your response to information provided by BC survivors and oncologists? |

Survivor. Patients feel that the true story of the BC Survivors found in the PERANTARA stirred their feelings because the women who have been diagnosed with cancer still have high spirits to undergo the process of examination and treatment. Also, they also feel touched because it turns out BC Survivor can still live their lives every day without feeling isolated. Therefore, they suggested that the survivors’ profiles could be added in the package. Oncologist. Oncologist’s advice was helpful and easy to understand. Patients stated that information about the diagnosis of breast cancer and its treatment was helpful knowledge. Also, information on risk factors and preventive action is valuable. |

| Presentation What is your opinion regarding the presentation/display of the PERANTARA? Use past tense to present patients’ opinions. I mean all you have written in the column named sub theme should be in past tense. |

Clarity. The language and images that used make the information more understandable. Patients recommend that fonts in the bubbles be enlarged and critical statements written in bold fontss. Attractiveness. The images and colors used make the PERANTARA more interesting and not boring. Alternatively, patients suggest using photos. |

Quantitative Analysis

As shown in Table 4 (Client’s Satisfaction Inventory), the large majority of patients (n=9; 75%) appeared to be satisfied with the help they had received from PERANTARA. According to patients, the quality of PERANTARA was good (n=8; 66,7%) and met their needs (n=6; 50%). Furthermore, we found that patients obtained the information they needed (n=6; 50%) and PERANTARA helped them to cope with their problems more effectively (n=7; 58,3%). Moreover, patients stated that they were willing to continue using PERANTARA (n=7; 58,3%) and to recommend this intervention packages to a friend who would need similar help (n=10; 83,3%).

Table 4.

Client’s Satisfaction Inventory

| Factors | Patient’s Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of the Materials | Poor | Fair (n=1, 8,3%) | Good (n=8, 66,7%) | Excellent (n=3, 25%) |

| Kind of Information | No, definitely | No, not realy (n=1, 8,3%) | Yes, generaly (n= 5, 41,7%) | Yes, definitely (n=6, 50%) |

| Met need | None of my needs have been met | Only a few of my needs have been met (n=2, 16,7%) | Most of my needs have been met (n=6. 50%) | Almost all my needs have been met (n=4, 33%) |

| Recommend to a friend | No,definitely | No, I don’t think so | Yes, I think so (n=2, 16,7%) | Yes, Definitely (n=10, 83,3%) |

| Amount of help | Quite Dissatisfied | Mildly Dissatisfied | Mostly Satisfied (n=9, 75%) | Very Satisfied (n=3, 25%) |

| Deal with problems | No, they seemed to make things worse | No, they really didn’t help | Yes, they helped (n= 5, 41,7%) | Yes, they helped a great deal (n=7, 58,3%) |

| Overall satisfaction | Quite Dissatisfied | Mildly Dissatisfied | Mostly Satisfied (n=8, 66,7%) | Very Satisfied (n=4, 33,3%) |

| Continue using the materials | No, definitely | No, I don’t think so | Yes, I think so (n=7, 58,3%) | Yes, Definitely (n=5, 41,7%) |

PERANTARA (self-help psychoeducation materials); Material 12 patients; Participant

Finalization

Based on the results of the pilot study, we made some revisions in the content and presentation of PERANTARA (Setyowibowo, 2017) . These revisions were made following consultation with an oncologist, a health communication expert, a health psychology expert, and BC survivors. The revisions were:

1) The printed materials were adapted (adapted in a form of Table Flipchart (See Table 5). The content of table flipchart consisted of: (1) What’s in my breast? a brief explanation of BC symptoms to enable patients to have an accurate understanding and motive them to seek help from oncologists as a reliable sources; (2) Why should I immediately consult a doctor? This part aimed to stimulate women to follow the examination procedure as soon as possible so that the disease can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible and to raise the patient’s awareness on her symptoms; and (3) You are not alone: the recommendation to seek support from significant persons and institutions is provided.

Table 5.

Final Script

| PERANTARA: Segera Periksa Ke Dokter Format: Table Flipchart Language: Indonesia |  |

| Target Population | Women with breast cancer symptoms (that can be presumed as related to breast cancer during the first visit to hospital). Demographic Status: middle to low level of education status, middle to low level of socio-economic status, live in the urban and rural area. |

| Behavior Objective | Reduce patient’s delay (Time to Diagnosis) |

| Key Content | |

|

Part 1 Profile. Oncologists. Breast Cancer Survivors |

|

Part 2. What’s on My Breast. A brief explanation of breast cancer symptoms for enabling the patients to have an accurate understanding and motivation to seek information/help from oncologists as a credible sources. |

|

Part 3. Why should immediately consult a Doctor? A stimulation to let the first breast examinations immediately be followed by a biopsy so that the disease can be diagnosed and treated early; and a brief explanation of breast examination procedure to raise the patient’s awareness on the their symptoms and willingness to follow the procedure. |

|

Part 4. You are not alone. Information showing that many people are around who care; Recommendation to seek support from significant persons and institutions. |

|

Personal Notes. Providing facilities (space) for patients to record some important things, for example: complaints, questions asked, doctor’s advices and other important notes |

| Title | KISAH NYATA DUA PEREMPUAN TANGGUH |

| Format | Audiovisual Story Telling - DVD |

| Language | Indonesia |

| Target Population | Female patients with breast cancer symptoms (that can be presumed as related to breast cancer during the first visit to a hospital). Demographic Status: middle to low level of education status, middle to low level of socio-economic status, live in the urban and rural area. |

| Behavior Objective | Reduce patient’s delay (Time to Diagnosis) |

| Short Description | The testimony of two survivors of breast cancer who shared their stories about their conditions, promoting active coping and seeking social support, and give recommendation to patients to consult a doctor immediately when they discover abnormalities in their breast. |

| Scene (Key Message) | |

| 1) Introduction. | |

| Sample script: “This is a true story of the struggles of two tough women, ever since they discovered any abnormalities in their breasts, until successfully through various challenges during the treatment process. Now, they are still actively working for the community and beloved family.” | |

| 2) Reduce delay. | |

| Sample script: “If we find the things that are suspicious, or anything different than usual, consult with a doctor or other health professionals, to assure what the problem is…” “Do not be too scared first because not all lumps are cancer. The important thing is consult to the doctor immediately to know the examination procedures.” | |

| 3) Coping with psychosocial issues. | |

| Sample script: “…When you go through the process of examination and treatment, probably will emerge feeling sad and lonely. You do not have to worry too much, because you are not alone. Many care about you! Ask your husband, family or friends to accompany you. Share stories, feelings and expectations need to be done…” “…My message to the family, especially to her husband, the emotional support to a spouse or who are undergoing examination or treatment of breast cancer is very important. Without the support of the husband, their spirit will fall." | |

| 4) Contacts | |

| Important list of address to gain support: informational, financial and emotional. | |

2) Audiovisual materials . We added brief summaries of the key messages given in the printed materials. Besides, we also added a profile photo of an oncologist and BC survivors to increase the credibility of the information sources. See Table 5 (Final Script) for the final outline of PERANTARA.

Discussion

In this study, we explained the process for the development of PERANTARA, a self-help psychoeducational material for Indonesian women with BC symptoms. Its development was an iterative process involving patients (women with BC symptoms, women with BC, and BC survivors), healthcare providers (nurses and oncologists), and a multi-disciplinary group (health psychologist, health communication, and audiovisual designer). First, we interviewed the patients since they were the potential target group for our intervention. Furthermore, we involved experts from various fields and BC survivors to review the intervention framework that we had designed based on the results gained in the inventory step. This was done since we had to consider the resources to develop and evaluate the intervention.

The PERANTARA development was based on data collected from previous studies investigating psychoeducational interventions in other populations. We found that using printed and audiovisual materials could be a potential option to deliver psychoeducation to women with BC-related complaints, especially when resources were limited in terms of money, facilities, and experts to provide face-to-face or group psychoeducation.

A strength of PERANTARA is the use of narrative storytelling to educate and to persuade women with BC symptoms to immediately undergo the examination process so that the disease can be immediately diagnosed and treated. The use of narratives is emerging as a strategy to educate, persuade, and prompt health behavior change. Some previous studies reported that delivery of health information through the use of narratives was intrinsically persuasive (Kreuter et al., 2007; Kreuter et al., 2010; Dahlstrom, 2014) and more acceptable for patients with low and adequate health literacy (Moran et al., 2016) and populations that had a strong oral tradition (Hinyard and Kreuter, 2007), such as Indonesia. It is noteworthy to mention that PERANTARA contained information about both medical and psychosocial issues related to BC symptoms and diagnosis procedure. It aimed to reduce diagnostic delays and to support patients with BC symptoms. Evaluation of the content by a BC survivor, an oncologist, and a health psychologist confirmed that the information was relevant for women with BC symptoms.

A limitation of this study was that we included a small sample of women with BC and BC symptoms who may not represent the larger population of women with BC symptoms in Indonesia. Therefore, we recommend conducting a clinical trial in order to evaluate the efficacy of PERANTARA in reducing the time to diagnosis of Indonesian women from the moment they discover BC symptoms.

The results indicated that most of the women with BC and BC symptoms who participated in the pilot study had positive reactions toward the intervention package and were willing to recommend PERANTARA to new patients with BC (symptoms).

This study provided a useful framework to develop and pilot test a newly psychoeducational intervention. Given that the results of the ongoing crossover-controlled trial were positive, our intervention can be applied within standard oncological care in Indonesia. With some adaptation, the PERANTARA might also be suitable for women diagnosed with BC who had delayed their treatment. Moreover, the development process of PERANTARA, as described in this study, can be used as a future template to develop psychoeducational materials for other patient groups. Future studies are recommended to develop some psychoeducational interventions to help the caregiver of BC patients to cope with their psychosocial challenges.

Statement conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the KWF Kankerbestrijding (the Dutch Cancer Society: number VU 2012-5572). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Abu-Helalah AM, Alshraideh AH, Al-Hanaqtah M, et al. Delay in presentation, diagnosis, and treatment for breast cancer patients in Jordan. Breast J. 2016;22:213–7. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleton S, Watson M, Rush R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a psychoeducational intervention for women at increased risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:41–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azhar Y, Achmad D, Lukman K, et al. Predictors of complementary and alternative medicine use by breast cancer patients in Bandung, Indonesia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2115–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.4.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber MD, Jack W, Dixon JM. Diagnostic delay in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:49–53. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess CC, Linsell L, Kapari M, et al. Promoting early presentation of breast cancer by older women: a preliminary evaluation of a one-to-one health professional-delivered intervention. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan L. Delay in breast cancer: implications for stage at diagnosis and survival. Front Public Health. 2014;2:87. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caplan LS, Helzlsouer KJ, Shapiro S, et al. Reasons for delay in breast cancer diagnosis. Prev Med. 1996;25:218–24. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capozzo MA, Martinis E, Pellis G, et al. An early structured psychoeducational intervention in patients with breast cancer: results from a feasibility study. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:228–34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c1acd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. Br J Nurs. 2008;17:38–43. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlstrom MF. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13614–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320645111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dastan NB, Buzlu S. Psychoeducation intervention to improve adjustment to cancer among Turkish stage I-II breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5313–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denny L, de Sanjose S, Mutebi M, et al. Interventions to close the divide for women with breast and cervical cancer between low-income and middle-income countries and high-income countries. Lancet. 2017;389:861–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31795-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN. 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012 [Online] 2012. Available: http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/pie_pop.asp?selection=224900&title=World&sex=2&type=0&window=1&join=1&submit=%C2%A0Execute%C2%A0 .

- 15.Freitas AG, Weller M. Patient delays and system delays in breast cancer treatment in developed and developing countries. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:3177–89. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320152010.19692014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukui S, Kugaya A, Okamura H, et al. A psychosocial group intervention for Japanese women with primary breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1026–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1026::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:777–92. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. Satisfaction with information and its association with illness perception and quality of life in Indonesian breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2999–3007. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. Consulting a traditional healer and negative illness perceptions are associated with non-adherence to treatment in Indonesian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014a;23:1118–24. doi: 10.1002/pon.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. Psychosocial and cultural reasons for delay in seeking help and nonadherence to treatment in Indonesian women with breast cancer: a qualitative study. Health Psychol. 2014b;33:214–21. doi: 10.1037/a0031060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahraus D, Sokolosky S, Thurston N, et al. Evaluation of an education program for patients with breast cancer receiving radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:266–75. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones JM, Cheng T, Jackman M, et al. Getting back on track: evaluation of a brief group psychoeducation intervention for women completing primary treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:117–24. doi: 10.1002/pon.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan TM, Leong JP, Ming LC, et al. Association of knowledge and cultural perceptions of Malaysian women with delay in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5349–57. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsu H, Hayashi N, Suzuki K, et al. Guided self-help for prevention of depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer. ISRN Nurs 2012. 2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/716367. 716367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:221–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, et al. Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maghous A, Rais F, Ahid S, et al. Factors influencing diagnosis delay of advanced breast cancer in Moroccan women. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:356. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2394-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsubara C, Green J, Astorga LT, et al. Reliability tests and validation tests of the client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ-8) as an index of satisfaction with childbirth-related care among Filipino women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:235. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia. October 2016 Breast Cancer Awareness Month. [Online] Jakarta: Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia; 2016. Available from URL: http://www.pusdatin.kemkes.go.id/resources/download/pusdatin/infodatin/InfoDatin-Bulan-Peduli-Kanker-Payudara-2016.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran MB, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, et al. A pilot test of the acceptability and efficacy of narrative and non-narrative health education materials in a low health literacy population. J Commun Healthc. 2016;9:40–8. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2015.1126995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norsa'adah B, Rampal KG, Rahmah MA, et al. Diagnosis delay of breast cancer and its associated factors in Malaysian women. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price AJ, Ndom P, Atenguena E, et al. Cancer care challenges in developing countries. Cancer. 2012;118:3627–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ram S, Narayanasamy R, Barua A. Effectiveness of group psychoeducation on well-being and depression among breast cancer survivors of Melaka, Malaysia. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19:34–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.110234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redaniel MT, Martin RM, Ridd MJ, et al. Diagnostic intervals and its association with breast, prostate, lung and colorectal cancer survival in England: historical cohort study using the clinical practice research datalink. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sander MA. Profil penderita kanker payudara stadium lanjut baik lokal maupun metastasis jauh di RSUP Hasan Sadikin Bandung (Profile of patients with advanced breast cancer both locally advanced and advanced stage metastases at Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung) Farmasains. 2011;1:2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Setyowibowo H, Sijbrandij M, Iskandarsyah A, et al. A protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a self-help psychoeducation programme to reduce diagnosis delay in women with breast cancer symptoms in Indonesia. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:284. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3268-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherman DW, Haber J, Hoskins CN, et al. The effects of psychoeducation and telephone counseling on the adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, et al. Outcomes from the Moving Beyond Cancer psychoeducational, randomized, controlled trial with breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6009–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unger-Saldana K. Challenges to the early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in developing countries. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:465–77. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of print materials and step pedometers on physical activity and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2352–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams SA, Schreier AM. The effect of education in managing side effects in women receiving chemotherapy for treatment of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:16–23. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E16-E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]