Abstract

Common bile duct (CBD) stones are a frequent problem in Chinese populations, and their incidence is particularly high in certain areas (Wang et al., 2013). In recent years, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have been the main surgical procedures for CBD stones, although each has different advantages and disadvantages in the treatment of choledocholithiasis (Loor et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017). For patients with large stones, a dilated CBD, especially concurrent gallstones, LCBDE is the preferred and most economical minimally invasive procedure (Koc et al., 2013). However, a T-tube is often placed during LCBDE to prevent postoperative bile leakage; this is associated with problems such as bile loss, electrolyte disturbance, and decreased gastric intake (Martin et al., 1998). In addition, the T-tube usually must remain in place for more than a month, during which time the patient’s quality of life is seriously compromised. Many skilled surgeons currently perform primary closure of the CBD following LCBDE, which effectively speeds up rehabilitation (Hua et al., 2015). However, even in sophisticated medical centers, the incidence of postoperative bile leakage still reaches ≥10% (Liu et al., 2017). Especially for a beginner, bile leakage remains a key problem (Kemp Bohan et al., 2017). Therefore, a safe and effective minimally invasive surgical approach to preventing bile leakage during primary closure of the CBD after LCBDE is still urgently needed.

Keywords: Choledochoscope, Gastroscope, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE), Nasobiliary drainage

Common bile duct (CBD) stones are a frequent problem in Chinese populations, and their incidence is particularly high in certain areas (Wang et al., 2013). In recent years, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have been the main surgical procedures for CBD stones, although each has different advantages and disadvantages in the treatment of choledocholithiasis (Loor et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017). For patients with large stones, a dilated CBD, especially concurrent gallstones, LCBDE is the preferred and most economical minimally invasive procedure (Koc et al., 2013). However, a T-tube is often placed during LCBDE to prevent postoperative bile leakage; this is associated with problems such as bile loss, electrolyte disturbance, and decreased gastric intake (Martin et al., 1998). In addition, the T-tube usually must remain in place for more than a month, during which time the patient’s quality of life is seriously compromised. Many skilled surgeons currently perform primary closure of the CBD following LCBDE, which effectively speeds up rehabilitation (Hua et al., 2015). However, even in sophisticated medical centers, the incidence of postoperative bile leakage still reaches ≥10% (Liu et al., 2017). Especially for a beginner, bile leakage remains a key problem (Kemp Bohan et al., 2017). Therefore, a safe and effective minimally invasive surgical approach to preventing bile leakage during primary closure of the CBD after LCBDE is still urgently needed.

Many nasobiliary drainage (NBD) and biliary stent placement techniques have been developed to minimize bile leakage after primary closure of the bile duct following LCBDE (Dietrich et al., 2014). These techniques include preoperative/intraoperative ERCP and NBD tube placement and intraoperative biliary stent implantation (Yi et al., 2015; Gupta, 2016; Lee and Yoon, 2016). These have effectively lowered the incidence of bile leakage. Based on the intraoperative ERCP NBD tube placement technique, we developed a laparoscopic NBD tube placement via gastroscopy combined with choledochoscopy because gastroscopy is a more common and proficient technique than duodenoscopy. In this study, combined gastroscopic and choledochoscopic transabdominal nasobiliary drainage (GC-NBD) was applied during primary closure of the bile duct following LCBDE by surgeons who had no previous experience with primary closure. No bile leakage was observed in our series. Compared with other techniques, this procedure has low technical requirements and good reliability; it can be widely carried out in the surgical departments of county hospitals.

In total, 22 eligible patients (14 men, 8 women; age range, 46–81 years; mean age, (65.30±20.23) years) from July 1 2017 to Oct. 30 2017 were enrolled in our study. The inclusion criteria were the presence of gallstones and CBD stones as confirmed by ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and a CBD diameter of >1 cm. The exclusion criteria were the inability to tolerate general anesthesia during routine preoperative examination, acute cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, concurrent intrahepatic bile duct stones, and flocculent or sandy stones in the bile duct. The patients’ clinical data including age, sex, operating time, blood loss, postoperative complications, hospitalization expenses, and postoperative hospital stay were collected and analyzed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients

| Demographic feature | Value |

| Age (year) | 65.30±20.23 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 14 |

| Female | 8 |

| Operating time (min) | 150.00±48.00 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 35.00±12.60 |

| Complication | 0 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (d) | 6.87±1.04 |

| Hospitalization expenses (CNY) | 21 134.68±995.32 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (n=22) or number

Eight surgeons participated in this study and were responsible for cholecystectomy+CBD lithotomy+primary closure of the CBD. A surgeon with experience in conventional LCBDE+T-tube drainage served as the main operator and was mainly responsible for performing the cholecystectomy, CBD incision for stone extraction, and primary suture of the CBD. Other surgeons performed primary closure for the first time.

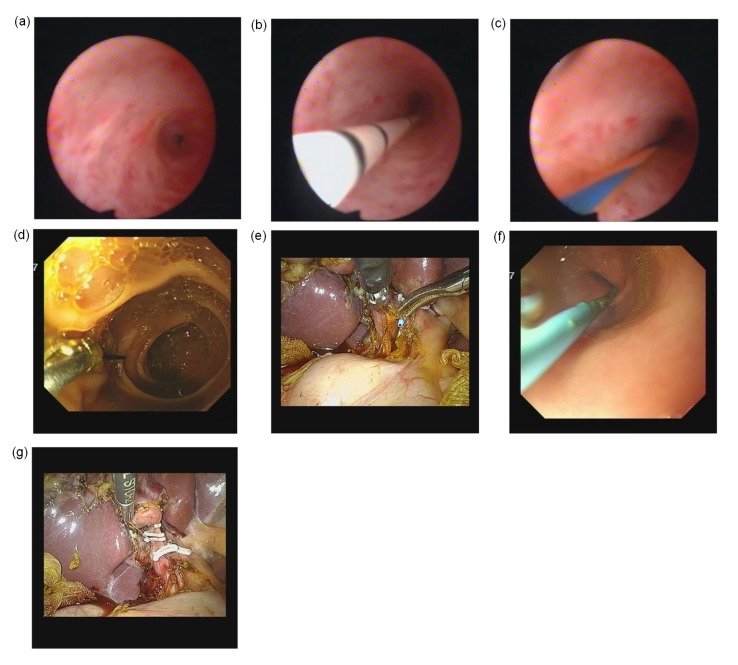

The surgical procedure involved seven steps (Fig. 1). (1) Establish pneumoperitoneum. The gallbladder triangle was separated, and the cystic artery was then clipped and transected; the cystic duct was also clipped. (2) The CBD was cut open and the CBD stones were completely removed by rinsing, clamping, or using a choledochoscopic basket. The intrahepatic bile duct and the lower end of the CBD were explored by choledochoscopy to confirm the absence of residual stones. (3) A guidewire was inserted into the duodenum opposite the papilla. (4) Pneumoperitoneum was stopped, and the gastroscope was inserted into the descending part of the duodenum. The head of the guidewire was clamped outside the gastroscope cavity. (5) Pneumoperitoneum was established to withdraw the choledochoscope. The NBD tube was inserted alongside the guidewire via the laparoscopic trocar. The tube was advanced into the duodenum along the guidewire under direct laparoscopic vision, and the head of the NBD tube was then placed into the common hepatic duct. The guidewire was slowly pulled out of the gastroscope cavity under direct gastroscopic vision. (6) The head of the NBD tube was held in the peritoneal cavity. The tail of the NBD tube was then pulled outside the nasal duct with the gastroscope, and the head of the tube was placed into the common hepatic duct. The CBD incision was sutured in a continuous pattern. (7) The cystic duct was transected, and the gallbladder was removed. Finally, the drainage tube was placed and the surgical incision sutured.

Fig. 1.

Surgical procedure

(a) The stones in the common bile duct were completely removed with a choledochoscope. A second examination was performed to confirm whether any residual stones were present in the bile duct. (b, c) Insertion of guidewire (c) via a tube (b) into the duodenum through the papilla under choledochoscopic vision. (d) The gastroscope was inserted into the duodenum to grasp the guidewire. (e) The head of the nasobiliary drainage tube was placed into the common hepatic duct under gastroscopic vision. (f) Gastroscopic placement of nasobiliary drainage tube in stomach. (g) Laparoscopic primary closure of common bile duct

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. All participants or their guardians gave written consent for their medical information to be used for scientific research.

The planned operations were successfully completed in all patients. No operation was converted to open surgery or T-tube drainage. The procedures lasted 130 to 210 min (mean, (150±48) min). The intraoperative blood loss volume was 5 to 50 mL (mean, (35.0±12.6) mL). All patients were discharged successfully, and no complications occurred. The abdominal drainage tube was withdrawn 3 to 5 d after surgery, and the NBD tube was removed 5 to 8 d after surgery. No one had bile leakage. Cholangiography was performed before removal of the NBD tube, and the absence of residual stones was confirmed. The contrast medium smoothly entered the duodenum. The postoperative hospital stay was 6 to 9 d, and the total cost of hospitalization was between 18 623 and 23 123 CNY.

In China, laparoscopic choledochoscopy (LC) combined with intraoperative ERCP to treat CBD stones has only been performed in a small number of general hospitals and has not become a routine procedure for CBD stones because of its need for highly skilled surgery. At present, the rate of primary closure following LCBDE remains low even in several top general hospitals in our province. T-tube placement during LCBDE remains a routine practice in most surgical settings. Compared with the applied ERCP+LC/LCBDE two-stage surgery and laparoscopic intraoperative ERCP, LCBDE+GC-NBD has the following advantages. (1) The technical requirement of gastroscopy is much lower than that of duodenal endoscopy. LCBDE+GC-NBD can be performed in many county hospitals. (2) LCBDE+GC-NBD is a one-stage operation, which speeds up the patient’s recovery, shortens the hospital stay, and reduces medical expenses. (3) The whole procedure is performed under general anesthesia, which makes the patients more comfortable compared with ERCP. (4) Intraoperative endoscopic NBD (ENBD) is performed without cutting open the papilla. It reduces endoscopic sphincterotomy-related complications such as perforation, bleeding, and pancreatitis.

Yin et al. (2017) reported the application of the LCBDE+intraoperative ENBD+primary closure of the CBD in the treatment of CBD stones. In their study, NBD was performed via gastroscopy and choledochoscopy for the first time. A total of 211 consecutive patients underwent LCBDE+intraoperative ENBD (Group A), and the other group underwent preoperative ERCP+subsequent LC (Group B). The incidence of postoperative bile leakage was 1.9% (4/211) in Group A, showing no significant difference when compared with Group B. However, Group A was significantly superior to Group B in terms of hospitalization time, hospitalization expenses, and the overall treatment-associated complication rate.

In a study by Xu et al. (2016), biliary stent drainage was used in LCBDE with primary closure which had a similar function to NBD. However, secondary bacterial infections may occur after biliary stent placement; therefore, the application of biliary stents in LCBDE remains controversial (Dietrich et al., 2014). Intraoperative biliary stenting is not in accordance with sterile surgical principles and is correlated with postoperative biliary tract infection. The safety of the primary suture of the CBD following biliary stenting requires further investigation in clinical studies with large samples. Therefore, this procedure has not been widely performed in the surgical setting.

Liu et al. (2017) retrospectively analyzed bile leakage after primary closure following LCBDE in 141 patients. The authors found that the incidence of postoperative bile leakage was 11.3% (16/141) and occurred more frequently in patients with a CBD diameter of <1 cm (up to 31.6%) and in the operation performed by inexperienced surgeons. The surgeons’ experience was a key factor influencing the success rate of primary closure following LCBDE. For surgeons who are beginners, preoperative or intraoperative NBD can effectively reduce or avoid the occurrence of postoperative bile leakage. Although most surgeons in the study had not performed primary closure following LCBDE before they participated in this project, they successfully completed the primary closure, and no bile leakage occurred postoperatively. It is very important that bile leakage can be confirmed by intraoperative saline injection or nasal cholangiography via NBD. A few interrupted stitches can be placed in such cases if necessary.

In the current study, using the same method described by Yin et al. (2017), we performed primary closure following LCBDE+intraoperative ENBD in 18 patients. No bile leakage was noted. The abdominal drainage tube was withdrawn 3 to 5 d after surgery, and the NBD tube was removed 5 to 8 d after surgery. The postoperative hospital stay was 6 to 9 d. This procedure has been applied in some county hospitals, indicating that it has low technical requirements and is highly feasible and reliable. For surgeons who are beginners in performing primary closure following LCBDE, combined gastroscopic and choledochoscopic transabdominal NBD may be a key technique for preventing postoperative bile leakage and thus warrants further clinical application.

Footnotes

Project supported by the Foundation Project for Medical Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (Nos. 2019ZH022 and 2018KY478) and the Zhejiang Province Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project (No. LGF19H180021), China

Contributors: Song-mei LOU, Zheng-rong WU, Gui-xing JIANG, Hua SHEN, Yi DAI, Yue-long LIANG, Li-ping CAO, and Guo-ping DING performed the surgery. Min ZHANG performed data analysis and edited the manuscript. Song-mei LOU and Guo-ping DING contributed to study design, writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and, therefore, have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Song-mei LOU, Min ZHANG, Zheng-rong WU, Gui-xing JIANG, Hua SHEN, Yi DAI, Yue-long LIANG, Li-ping CAO, and Guo-ping DING declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

References

- 1.Dietrich A, Alvarez F, Resio N, et al. Laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones: transpapillary stenting or external biliary drainage? JSLS. 2014;18(4):e2014–00277. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta N. Role of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration in the management of choledocholithiasis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(5):376–381. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i5.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua J, Lin SP, Qian DH, et al. Primary closure and rate of bile leak following laparoscopic common bile duct exploration via choledochotomy. Dig Surg. 2015;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000368326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp Bohan PM, Connelly CR, Crawford J, et al. Early analysis of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration simulation. Am J Surg. 2017;213(5):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koc B, Karahan S, Adas G, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography plus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2013;206(4):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Yoon YC. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration using V-Loc suture with insertion of endobiliary stent. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(6):2530–2534. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu DB, Cao F, Liu JF, et al. Risk factors for bile leakage after primary closure following laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Surg, 17:1. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12893-016-0201-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loor MM, Morancy JD, Glover JK, et al. Single-setting endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and cholecystectomy improve the rate of surgical site infection. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(12):5135–5142. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin IJ, Bailey IS, Rhodes M, et al. Towards T-tube free laparoscopic bile duct exploration: a methodologic evolution during 300 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg. 1998;228(1):29–34. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang B, Guo ZY, Liu ZJ, et al. Preoperative versus intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with gallbladder and suspected common bile duct stones: system review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2454–2465. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu YK, Dong CY, Ma KX, et al. Spontaneously removed biliary stent drainage versus T-tube drainage after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(39):e5011. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi HJ, Hong G, Min SK, et al. Long-term outcome of primary closure after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration combined with choledochoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25(3):250–253. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin P, Wang M, Qin RY, et al. Intraoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage over primary closure of the common bile duct for choledocholithiasis combined with cholecystolithiasis: a cohort study of 211 cases. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(8):3219–3226. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Zha WZ, Wu XD, et al. Three modalities on management of choledocholithiasis: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;44:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]