Abstract

Objective:

The human insula is increasingly being implicated as a multimodal functional network hub involved in a large variety of complex functions. Due to its inconspicuous location and highly vascular anatomy, it has historically been difficult to study. Cortico-cortical evoked potentials (CCEPs), utilize low frequency stimulation to map cerebral networks. They were used to study connections of the human insula.

Methods:

CCEP data was acquired from each sub-region of the dominant and non-dominant insula in 30 patients who underwent stereo-EEG. Connectivity strength to the various cortical regions was obtained via a measure of root mean square (RMS), calculated from each gyrus of the insula and ranked into weighted means.

Results:

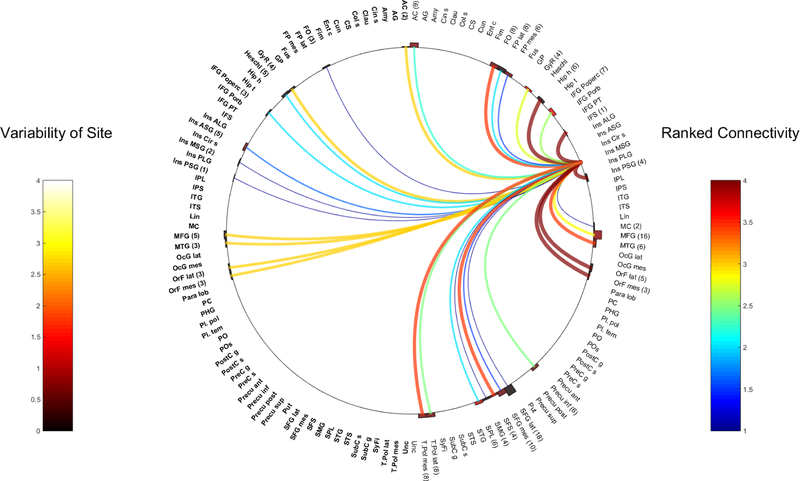

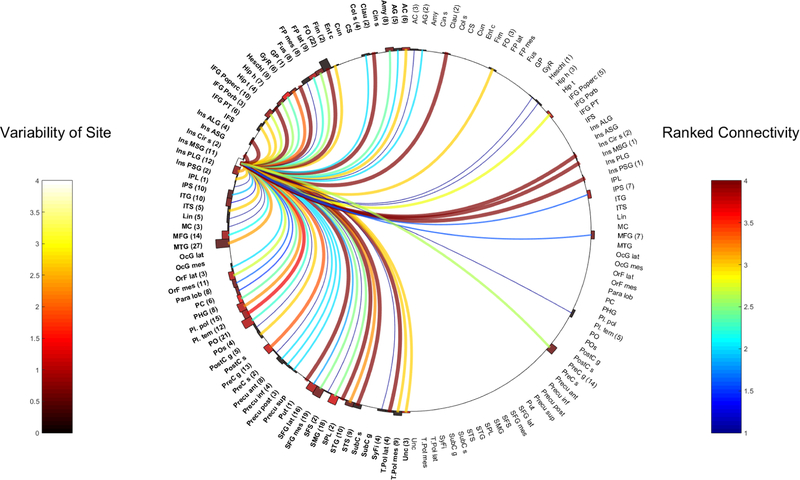

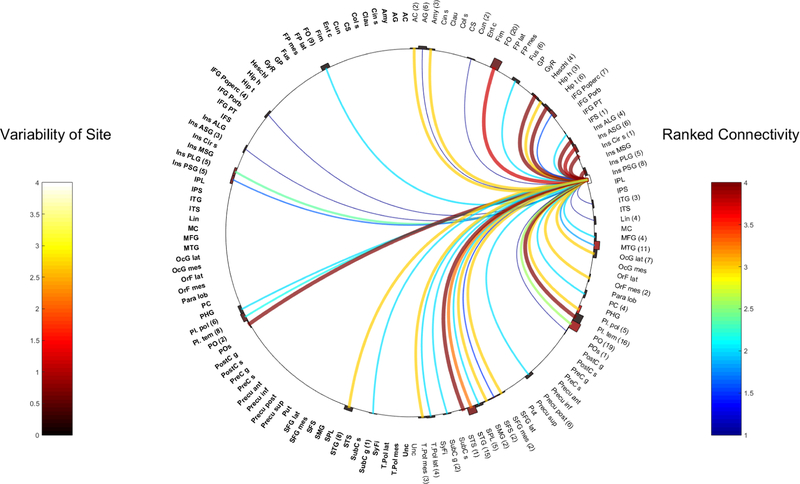

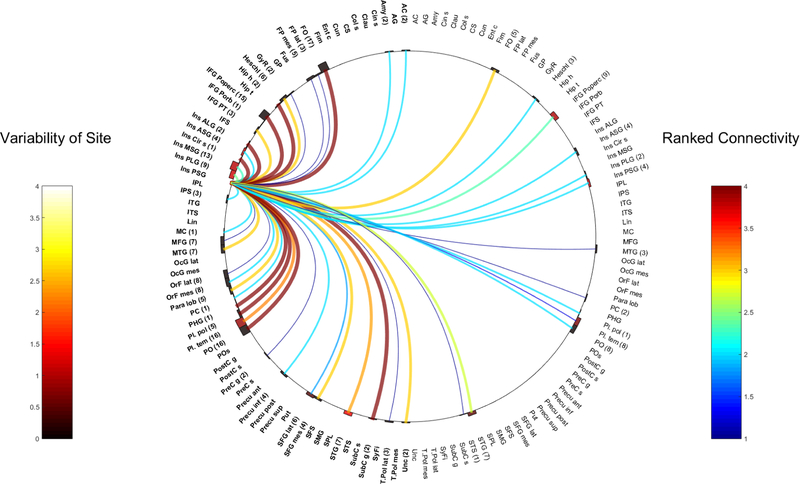

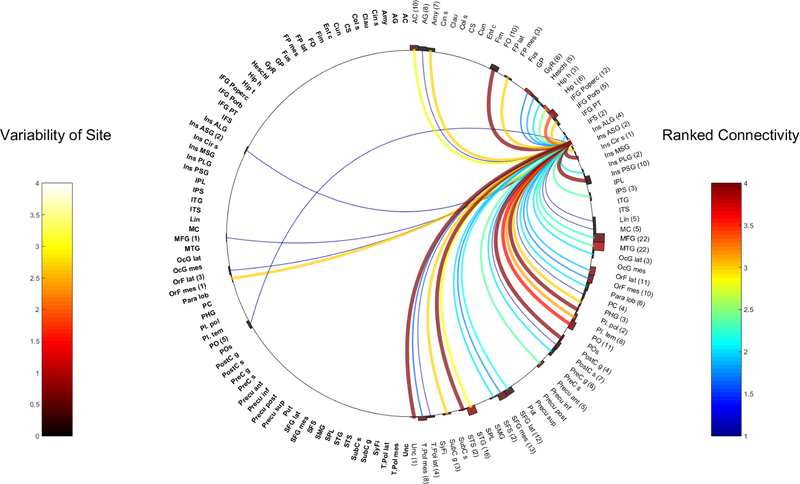

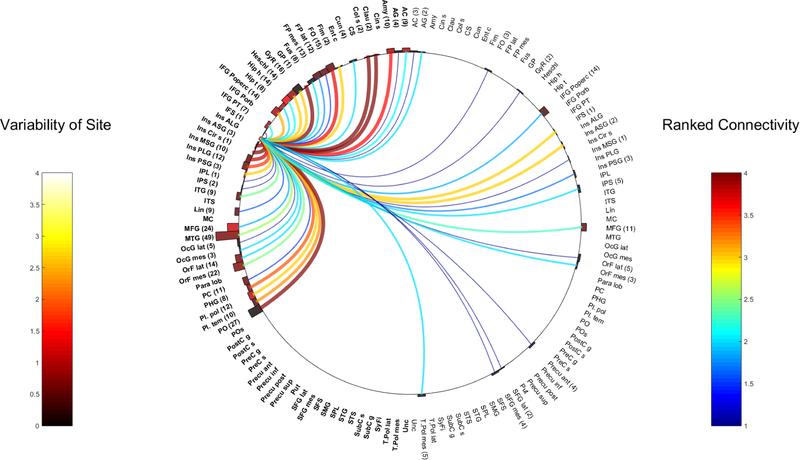

The results of all cumulative CCEP responses for each individual gyrus were represented by circro plots. Forty-nine individual CCEP pairs were stimulated across all the gyri from the right and left insula. In brief, the left insula contributed more greatly to language areas. Sensory function, pain, saliency processing and vestibular function were more heavily implicated from the right insula. Connections to the primary auditory cortex arose from both insula regions. Both posterior insula regions showed significant contralateral connectivity. Ipsilateral mesial temporal connections were seen from both insula regions. In visual function, we further report the novel finding of a direct connection between the right posterior insula and left visual cortex.

Significance:

The insula is a major multi-modal network hub with the cerebral cortex having major roles in language, sensation, auditory, visual, limbic and vestibular functions as well as saliency processing. In temporal lobe epilepsy surgery failure, the insula may be implicated as an extra temporal cause, due to the strong mesial temporal connectivity findings.

Keywords: brain networks, connectivity, cortico-cortical evoked potentials, epilepsy, insula, stereo-EEG

INTRODUCTION

Over the recent years, technological advances in noninvasive neuroimaging have further expanded a fundamental concept in neuroscience, namely, that the nervous system is an interconnected and intercommunicating network of neurons [1]. Unraveling these networks has provided the basis of the human connectome; a comprehensive description of the structural connectivity of the brain [2]. Within this structural connectome, lies a plasticity and hierarchy, designated by systems neuroscience as functional connectivity-statistically inter-dependent brain regions during which integration results in specific neurophysiological events and effective connectivity which refers to the influence of one neural system exerting its influence over another [3].

Cortico-cortical evoked potentials “CCEPs”, is a relatively novel in vivo brain mapping technique, utilizing low frequency stimulation, in patients undergoing invasive monitoring for refractory epilepsy [4]. CCEP mapping represents a form of evoked effective connectivity. Here, there is a causal influence between brain regions, where one region may influence another but not vise-versa. For example, stimulation at one site (independent measure) may result in evoked responses (dependent measure) at distant sites, but this relationship may not be reciprocal. Unlike functional connectivity, effective connectivity is a direct measure of this influence.

CCEPs have significant properties including notable spatial-temporal resolution, the ability to sample across distributed networks and the ability to accurately localize the stimulation site [5]. CCEPs have been previously utilized to define networks pertaining to language [4], limbic [6] and motor systems [7] as well as preferential excitability of seizure onset regions [8,9].

The human insula has been viewed as an enigmatic cortical region. This is partly due to its anatomical location nestled behind the frontal, temporal, and parietal opercular cortices and dense surrounding vascular network which has made it historically a challenge to study [10,11]. The adult anterior insula comprises three anterior short gyri (anterior, middle and posterior), separated from the posterior insula by a central insula sulcus. The posterior insula comprises the two long gyri (anterior and posterior) [12,13].

Despite covering only 2% of the cerebral cortex, the insula acts as a highly diverse functional highway implicated in a vast number of homeostatic, cognitive and affective processes. These include; vestibular, visceromotor and viscerosensory functions, somatomotor, pain and temperature, motor association, ocular motor, language, limbic integration, auditory function and also spans the realms of cognition including memory, body awareness, emotion and self recognition [14,15].

How the insula is able to integrate and be involved in such a wide array of functions has prompted attempts to uncover its connectivity networks. Initially such discoveries were based on tracer injection studies and dissection in both humans and primates [16–8]. With the advent of diffusion tractography and advanced fMRI algorithms, further insula connections were observed in vivo [19–21].

Given the significant efferent output from the insula, it comes as no surprise that it may potentially be able to mimic epilepsies arising from any lobe of the brain and also account for epilepsy surgery failure in temporal, frontal and parietal lobe epilepsy surgery [22–25]. Thus, the importance of sampling the insula by intracranial electrodes in lesion-negative refractory epilepsy is increasingly being recognized.

Despite this however, there are still only a handful of reports using CCEP methodology, which has attempted to describe the connections of the human insula [26–29].

In this study, CCEP data of individual gyri in the dominant and non-dominant insula was analysed, in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery with Stereo-Electroencephalography. Maps of connectivity measures, based on the averaged root mean square (RMS) values, were generated highlighting the connectivity strength of various cortical regions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all inclusion/exclusion criteria, whether inclusion/exclusion criteria were established prior to data analysis, all manipulations, and all measures in the study.

This retrospective analysis utilized 192 patients who underwent SEEG evaluation in 2014 (99 patients) or 2015 (93 patients) for epilepsy surgery. SEEG electrodes were typically 6 to 16 contacts, 2.5mm long, 0.8mm diameter, separated by 2 mm of space. Placement into the insula was either in an orthogonal or oblique manner depending on the desired coverage. Patients with electrode contacts in either of the insula regions were selected (n= 71). CCEPs were performed with the patient on full medications at the end of the evaluation.

Of the 71 patients, 42 patients had CCEPS performed in either insula region. To standardize inter-regional connectivity, patients with previous epilepsy surgery, insula abnormalities on MRI or seizure onset in the insula, were excluded (9 patients). A further 3 patients were excluded because there was ambiguity as to whether the electrode was sampling the insula or an adjacent structure (e.g. operculum). In total, 30 patients were selected for ongoing analysis.

The methods for obtaining CCEPs at our center have previously been outlined [4]. Stimulation was performed with the Grass S88 stimulator (Warwick, RI, USA) using an automated interface in Nihon-Kohden software. A paradigm using 1Hz stimulation with 0.3msec square wave pulses of alternating polarity between two adjacent electrode contacts located in the desired anatomical region was utilized. 30 trails were performed at 2mA, 4mA and 6mA intensities and 60 trials at the 8mA setting. This stimulation protocol is safe and would not cause localized tissue injury [30]. Stimulus intensity was truncated if after discharges or seizures had occurred.

Anatomical analysis and determining regions of interest

The anatomical location of each electrode contact, for every stereo-EEG case, had previously been tabulated for clinical use. Confirmation of electrode placement for all 30 patients was re-reviewed using the CT and MRI reconstructions assembled via the Curry Neuroscan software (Compumedics, USA), prior to any CCEP analysis. In particular, the insula contacts were analysed for their location with the insula itself. Any contacts that were extra-cerebral, placed in white matter or showed continued artifact, were removed from analysis. An aggregate of all the electrode contacts, across all 30 patients, superimposed onto a standardized MNI-space template, is shown in supplementary figures 11 and 12

CCEP analysis

The raw SEEG electrode CCEP averaged data was extracted from the 256-channel montage display of the Nihon Kohden digital EEG machine (NeuroWorkbench version 05–20; Nihon Kohden America, Inc., CA, USA). These raw CCEP-SEEG epoch files were then reviewed in MATLAB (MATLAB, Matworks Inc.). Synchronization pulses were captured in the NK software to define the precise time of the stimulation event. The evoked response, sampled at 1000Hz, was then bandpass filtered at 1–300Hz and notch filtered at 60Hz. The selected time window parameters included a 100msec baseline period prior to stimulation onset and 400msec time window following the onset of stimulation. Averaged evoked potentials acquired at stimulation amplitudes of 2, 4, 6 and 8mA were analyzed.

CCEP responses using subdural grid recordings have been reported to comprise two peaks-an early N1 and late N2 negative response. However in SEEG, there are often inconsistencies in the CCEP morphology, in part due to electrodes located within sulci or traversing grey and white matter [31]. Rather than relying on the latency or amplitude of the response, analysis of the root mean square (RMS) is utilized to quantify its strength. The RMS (quadratic mean) is a statistical measure of signal amplitude, representing the average absolute deviation of a signal in time, performed by taking the square root of the sum of the squared terms. We compared the ratio of the baseline RMS value at 100ms before a stimulation pulse and compared this to the RMS value at 10 to 300 milliseconds after stimulation. A kurtosis method (threshold setting at 8) was utilized to reject stimulation artifact, but not large evoked responses [32]. Rejected items were manually analyzed to confirm the presence of a stimulation artifact and not an exaggerated evoked potential.

Responses to CCEP stimulation were based on RMS values. These were calculated upon the averaged evoked potentials and baselines, consistent with prior CCEP methodology [4,6]. Electrode contacts were grouped by anatomical region of interest (ROI), with results in the same ROI averaged in order to give a connectivity summary for that ROI. It was assumed that stimulations from the same anatomical area would activate the same network, therefore if multiple stimulations were performed within the same gyri in a patient, results were averaged across stimulations. These results were ranked into Quartile Values (QV) for each ROI for the stimulated gyri, giving values of 4 (maximal) to 1. To allow for comparison between patients, weighted means (WM) were computed for RMS quartile values, which took into account the number of trials incorporated in the QV. Standard deviation of results across patients for each QV were also computed to see if the spread was large for an ROI. QVs were shown on specialized circro plots, which captured the connections of the stimulated gyri. Since this research was exploratory in nature, there were no hypotheses tested, and therefore, the standard deviation can be thought of as a reliability check for results, with larger spreads considered less reliable. Epileptic contacts were also left in the analysis for completeness.

Circle maps

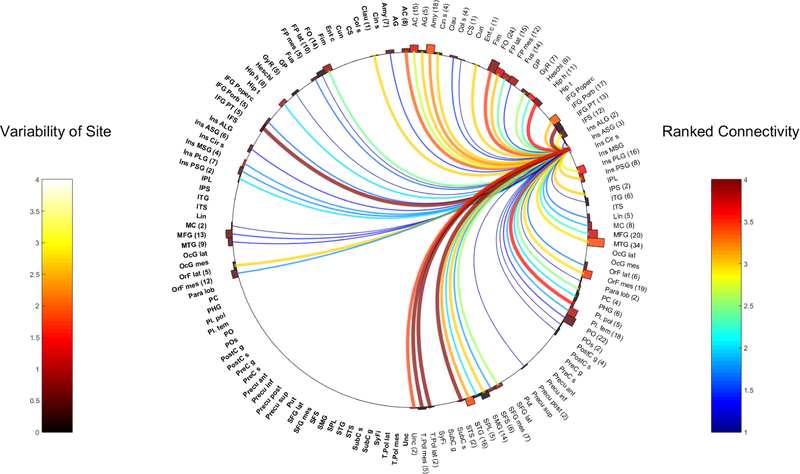

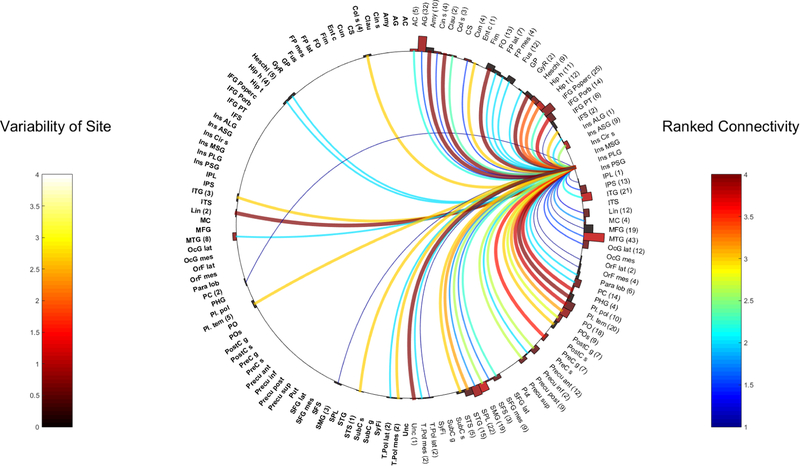

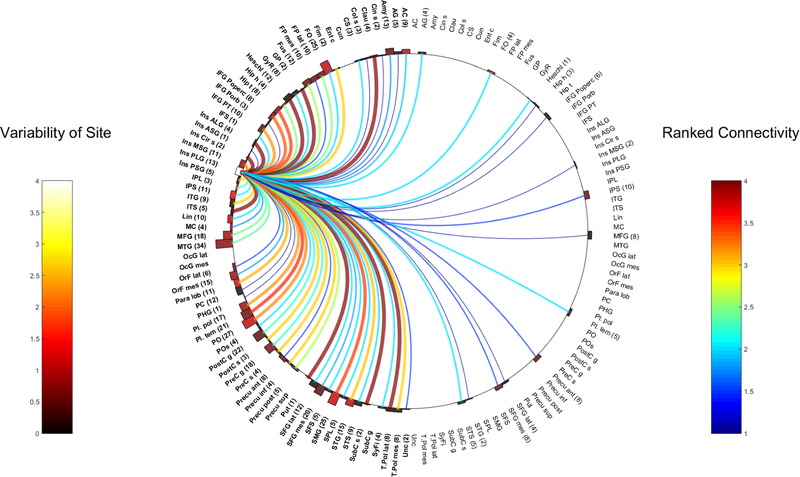

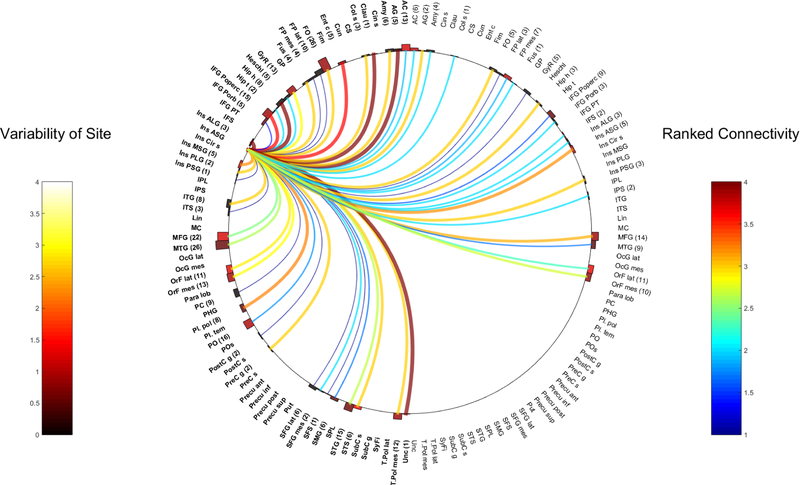

Circro plots denote the projections of the stimulation site graphically and were created using a modified open source toolbox (https://github.com/bonilhamusclab/circro). The plots are organized so that right hand anatomical sites, representing the right hemisphere, are in bold, and left hemisphere anatomical sites placed on the left. Total anatomical sites differed slightly between the various gyri stimulated as there was variability in sampling across patients, due to individualized hypotheses in Stereo-EEG.

The number following the anatomical site indicates how many contacts and patients were sampled during stimulation of a particular insula gyrus. Heights of columns on the circle border illustrate the number of electrode contacts sampled graphically, and the colour highlights the standard deviation of the responses across patients, which may be thought of as a reliability measure since no statistical analysis could be performed. Lines between sites show the strength of connectivity between ROIs, with colours representing the WM of QV’s. The thickness of the line indicates the relative number of electrode contacts sampled at the response site, normalized by the number of contacts in the most sampled site on each plot. The colour bars on left and right show the scales for both standard deviation and weighted mean of quartile values. Because of the number of connections, a circro plot for each insula gyri was created.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the patient demographics for all 30 patients. Dominant language areas were in the left hemisphere for all patients, including the 3 patients who were left handed and shown to be left dominant by WADA testing. Right and left gyri are denoted by and “R-” and “L-” prefix, respectively. Due to the volume of the data, only significant connections with a weighted mean QV greater than 3 are discussed, as these connections are considered to be the most robust. Circro plots are shown for each individual gyrus in figures 1–10 with anatomical abbreviations provided in Table 2. The complete data set is available in supplementary Table 3, with all the total number of all electrodes sampling all anatomical regions provided in supplementary Table 4.

Table 1:

Patient Demographics

| Age/hand | Age Onset | SEEG Seizure focus | MRI | FDG-PET | SPECT | Insular Contact | Insula 50Hz Stimulation | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19y/RH | 7y | Left Middle Frontal Gyrus (MFG) | Mild dysplasia L hippocampus | Bitemporal hypometabolism without asymmetry. | Hyperperfusion in L dorsal lateral central, adjacent frontal opercular, and posterior insula. | L MSG | Throat sensation (dry) | Left MFG resection |

| 21y/R H | 9y | Left orbitofront al and mesial temporal | Slight asymmetric enlargement of L amygdala | Reduced FDG activity in b/l mesial temporal lobes including mesial temporal regions. | N/A | L ALG | N/A | Left orbitofrontal and temporal |

| L MSG | N/A | |||||||

| 20y/R H | 14y | Left Middle temporal gyrus (MTG) | Unremarkable | Hypometabolism in L lateral anterior temporal lobe. | B/l Hyperperfusion in cluster areas of L temporal, frontal and parietal region. | L ALG | N/A | Left temporal lobectomy |

| 28y/R H | 5m | Not localizable | Unremarkable | Bitemporal & L parietal hypometbolism. | Hyperperfusion in R posterior frontal, R temporal, and L anterior parietal lobe | L MSG | N/A | NA |

| L PSG | N/A | |||||||

| L PLG | N/A | |||||||

| 34y/R H | 24y | Left temporal | Unremarkable | B/l moderate hypometabolism in mesial temporal lobes | N/A | L ASG | N/A | Left temporal lobectomy |

| 43y/R H | 5y | Right frontal operculum | R frontal opercular cortical malformation, b/l hippocampal volume loss | Mild hypometabolism in b/l anterior medial temporal regions | Hyperpefusion in R posterior insular region or R dorsal lateral central region | R ALG | L hand burning | Frontal operculum |

| L ASG | N/A | |||||||

| 39y/R H | 18y | Right frontal operculum | Unremarkable | B/l hypometabolism in anterior mesial temporal regions, more on the R side | N/A | R PLG | L hand tingling | Frontal operculum |

| R ASG | Nil | |||||||

| R ASG | Nil | |||||||

| 49y/R H | 22y | Bilateral orbitofront | Encephalomalacia in L frontal lobe | Left frontal hypometabolism | N/A | R MSG | N/A | NA |

| 61y/R H | 10y | Left temporal | Unremarkable | Severe hypometabolism in L mesial temporal lobe | Hyperperfusion in cluster area of L basal frontal or L lateral deep parietal region | L MSG | Difficulty reading | L lateral temporal lobectomy |

| L PLG | Painful electric shock in R calf | |||||||

| L ALG | Loss of verbal fluency | |||||||

| L PLG | N/A | |||||||

| 20y/R H | 5y | Right pars orbitalis | Unremarkable | Mild bitemporal and focal hypometabolism in R mid to anterior dorsomedial frontal cortex. | Hyperperfusion in both hemispheres in R posterior dorsal medial frontal, R posterior basal medial temporal and L mid cingulate gyrus. | R ASG | N/A | Right pars orbitalis |

| 12y/R H | 4m | Right Superior Frontal Gyrus (SFG) | Unremarkable | Mild-moderate bitemporal hypometabolism. | No dominant foci of ictal hyperperfusion. | R MSG | N/A | Right superior frontal resection |

| R MSG | N/A | |||||||

| 30y/L H | 10y | Right temporal | Unremarkable | B/l temporal hypometabolism more pronounced on the R | N/A | R ALG | N/A | Right temporal lobe resection |

| R MSG | N/A | |||||||

| 27y/R H | 17y | Right Superior Frontal Gyrus (SFG) | Unremarkable | Bitemporal hypometabolism | N/A | R Circ S | N/A | Right superior frontal resection |

| 36y/L H | 1y | Right superior and Middle frontal gyrus | Unremarkable | Mild b/l temporal and frontal parasaggital hypometabolism | Hyperperfusion in L medial parietal and occipital regions | R Circ S | Whole body parasthesias | Right frontal resection |

| 38y/R H | 31y | Right neocortical temporal lobe | Unremarkable | Hypometabolism with mild asymmetry in R anterior medial basal temporal region | Hyperperfusion in R superior temporal, frontal operculum and posterior insula | R PLG | Left hemibody parasthesias | Right temporal lobe resection |

| 20y/R H | 9y | Multifocal | B/L schizencephaly and pachygyria in the parietal regions. | N/A | Hyperperfusion in bilateral temporal, opercular regions and left posterior insular region | R ASG | N/A | No surgery |

| R PSG | N/A | |||||||

| L PSG | R hand tingling | |||||||

| 53y/R H | 35y | Left mesial temporal region | Questionable asymmetric cortical thickening of inferior margin of L anterior temporal pole | Asymmetric hypometabolism involving L anterior temporal lobe, L orbitofrontal and L insula regions | N/A | L ASG | N/A | Left temporal lobectomy |

| 25y/R H | 4.5y | Multifocal regions | L hippocampus MTS, abnormal sulcation at rectus gyrus and anterior interior frontal lobe | Severe hypometabolism Left hemisphere | Hyperperfusion in L mid to anterior temporal regions extending to the L insular region. Also in L anterior medial frontal regions extending to the R mid cingulate gyrus. | L PSG | Nil | No surgery |

| L ALG | Nil | |||||||

| 28y/R H | 19y | Right Temporal | Heterotopic gray matter in R medial temporal lobe | Bitemporal hypometabolism | Hyperperfusion in L posterior basal frontal region, b/l insula and dorsal central regions | R MSG | N/A | Right temporal lobectomy |

| 35y/R H | unkno wn | Right mesial temporal region | Unremarkable | B/l temporal, parietal and occipital hypometabolism. R temporal asymmetry | N/A | R ASG | N/A | Right anterior temporal lobectomy |

| 32y/R H | 4y | Left Parietal Operculum | Unremarkable | Bitemporal hypometabolism without asymmetry. Mild hypometabolism in L parietal operculum region. | Hyperperfusion in L parietal operculum, L medial occipital, L lateral temporal and occipital regions | L PLG | Whole body sensation | No surgery |

| 54y/R H | 25y | Right temporal region | Unremarkable | Focal hypometabolism in R mesial R temporal | N/A | R PLG | N/A | Right temporal lobectomy |

| 31y/R H | 8m | Right Angular gyrus | Unremarkable | Bitemporal hypometabolism with asymmetry in R mesial temporal, R orbitofrontal, R anterior parasagittal frontal, R parietal operculum | Hyperperfusion in R basal medial temporal occipital junction | R PLG | N/A | Right parietal resection |

| 52y/R H | 5y | B/L temporal | Unremarkable | Diffuse cortical hypometabolism, | N/A | R ASG | N/A | Neuropace |

| L ASG | ||||||||

| 24y/R H | 15y | Right temporo-occipital regions | Unremarkable | Bitemporal hypometabolism with R lateral temporal asymmetry | Hyperperfusion in R lateral temporal parietal region | R PLG | Auditory- high pitch sound | Right temporo-occipital resection |

| 69y/R H | unknown | Left Mesial temporal | Unremarkable | N/A | Hyperperfusion in L posterior lateral temporal region | L PLG | R foot painful stabbing sensation | Left temporal lobectomy |

| L MSG | N/A | |||||||

| 45y/R H | 5y | Right temporal lobe | Bilateral hippocampal symmetric hyperintensity in T2/FLAIR with mild volume loss. | Diffuse hypometabolism in b/l temporal lobes more pronounced on the R. | Hyperperfusion in both hemispheres in areas of R posterior basal frontal regions and R mid deep medial frontal region | R ASG | Nil | Right temporal lobectomy |

| R PLG | Warm feeling and parasthesias in both arms | |||||||

| 17y/L H | 6y | Right planum temporale and parietal operculum | Unremarkable | Hypometabolism of b/l parietal lobes more pronounced in the superior, parasagittal regions and bilateral temporal lobes more pronounced on the L | N/A | R ALG | L arm numbness | No surgery |

| 23y/R H | 14y | Left orbitofront al | Unremarkable | L frontal and temporal hypometabolism | N/A | L PLG | N/A | L orbitofrontal |

| 27y/R H | 10y | R hemisphere multifocal epilepsy | Subependymal heterotopia along atrium of R lateral ventricle. Thickened cortex in R frontal operculum | Hypermetabolism in R anterior supramarginal gyrus | N/A | R PLG | N/A | Neuropace |

| R PSG |

Patient data collectionAbbreviation - y: year, m: month, R: R, L: L, N/A: not applicable, FCD: focal cortical dysplasia, RH: R-handed, LH: L-handed, b/l: bilateral, ASG: Anterior short gyrus, MSG: Middle short gyrus, PSG: Posterior short gyrus, ALG: Anterior long gyrus, PLG: Posterior long gyrus

Fig. 1.

Right ASG

Fig. 10.

Left PLG

Table 2:

| AC- Anterior Cingulate | Hip t- Hippocampal tail | MTG- Middle temporal gyrus | Precu post- Precuneus posterior |

| AG- Angular Gyrus | IFG PO- Inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis | OcG lat- Occipital gyrus lateral | Precu sup- Precuneus superior |

| Amy- Amygdala | IFG POrb- Inferior frontal gyrus pars orbitalis | OcG mes- Occipital gyrus mesial | Put- Putamen |

| Cin s- Cingulate Sulcus | IFG PT- Inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis | OrF lat- Orbitofrontal lateral | SFG lat- Superior frontal gyrus lateral |

| Clau- claustrum | IFS- Inferior frontal sulcus | OrF mes- Orbitofrontal mesial | SFG mes- Superior frontal gyrus mesial |

| Col s- Collateral Sulcus | Ins ALG- Insula anterior long gyrus | Para lob- Paracentral lobule | SFS- Superior frontal sulcus |

| CS- Central Sulcus | Ins ASG- Insula Anterior short gyrus | PC- Post Cingulate | SMG- Supramarginal gyrus |

| Cun- Cuneus | Ins Cir s- Insula circular sulcus | PHG- Parahippocampal gyrus | SPL- Superior parietal lobule |

| Ent c- Entorinhal cortex | Ins MSG- Insula middle short gyrus | Pl. pol- Planum polare | STG- Superior temporal gyrus |

| Fim- Fimbriae | Ins MSG- Insula middle short gyrus | Pl. tem- Planum Temporale | STS- Superior temporal sulcus |

| FO- frontal operculum | Ins PSG- Insula posterior short gyrus | PO-Parietal Operculum | SubC s- Subcentral sulcus |

| FP lat- Frontal pole (lateral) | IPL- Inferior parietal lobule | PO s- Parieto-occipital sulcus | SubC g- Subcentral gyrus |

| FP mes- Frontal pole (mesial) | IPS- Inferior parietal sulcus | PostC g- Post central gyrus | SyFi- Sylvian Fissure |

| Fus- Fusiform | ITG- Inferior temporal gyrus | PostC s- Post central sulcus | T.Pol lat- Temporal pole lateral |

| GP- Globus pallidus | ITS- Inferior temporal sulcus | PreC g- Precentral gyrus | T.Pol mes- Temporal pole mesial |

| GyR- Gyrus Rectus | Lin- Lingula | PreC s- Precentral sulcus | Unc- Uncus |

| Heschl- Heschl’s gyrus | MC- Mid cingulate | Precu ant- Precuneus anterior | |

| Hip h- Hippocampal head | MFG- Middle frontal gyrus | Precu inf- Precuneus inferior |

The Anterior Short Gyrus (ASG)

Six patients had CCEPs in the R-ASG, with one patient having two electrode pairs located within the R-ASG, totaling 7 separate pairs of CCEP stimulations. A total of 639 electrode contacts in 76 bilateral grey matter regions were analyzed. 457 contacts were located in the right hemisphere across 46 anatomical areas, while 182 contacts in the left hemisphere accounted for 30 anatomical regions.

Five pairs of electrodes from the L-ASG had CCEP responses obtained from 5 patients. A total of 430 electrodes were analyzed across 67 regions of the brain, with 125 contacts in the right hemisphere, across 28 anatomical areas and 305 contacts in the left hemisphere derived from 39 regions.

Figures 1 and 2 represent all the various connections of the insula ASG across these contacts.

Fig. 2.

Left ASG

Ipsilateral connections:

Frontal connections:

Both ASG had strong connections to the frontal opercular regions (right-24 contacts, WM 3.5 and left 26 electrodes, WM 3). Both areas were also strongly connected to the inferior frontal gyrus-pars opercularis (right-22 electrodes, WM 4 and left-15 electrodes, WM 3.6).

Differences between the right and left ASG were seen in connections to the following: Lateral pre-frontal areas. The R-ASG connections were strongly represented in the inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis (PT) and orbitalis (PO) (13 and 17 electrodes respectively) and also in the lateral frontal pole (15 contacts). In contrast the L-ASG had only a very weak connection to pars orbitalis (WM 1.4, 5 electrodes) and to the entire frontal pole contacts (WM 1 in a total of 14 electrodes from mesial to lateral). No IFG pars triangularis representation was available on the left.

The L-ASG also strongly linked to the primary motor area (2 contacts). This was not seen with the right.

Temporal connections:

Shared strongly connected common efferents from the right and left ASG, were seen in the following temporal lobe locations:

Mesial temporal areas (R-ASG: uncus (2 contacts), hippocampal head (11 contacts), amygdala and entorhinal cortex (18 and 1 contacts respectively), and L-ASG: hippocampal head (8 contacts), uncus (1 contact,), entorhinal cortex (5 contacts), amygdala and collateral sulcus (6 and 3 contacts respectively))

temporal pole (R-ASG; mesial to lateral 7 contacts), L-ASG; mesial temporal pole (12 contacts)

temporal neocortical areas (R-ASG; superior temporal sulcus (STS) 2 contacts and superior temporal gyrus (STG) 16 contacts). L-ASG; STS (6 electrodes).

temporal operculum (anterior) (R-ASG; planum polare (5 contacts), L-ASG planum polare (8 contacts)

Differences in the strength of connectivity was found between the L-ASG which was seen to have a strong connections in the basal temporal region (fusiform gyrus (4 contacts, WM 3), ITG (8 contacts, WM 3) while the R-ASG was poorly connected to these areas (fusiform, 14 contacts, WM 1.4 and ITG 6 contacts WM 1).

Parietal connections:

Both ASG were highly connected to the angular gyrus

Differences included the R-ASG being strongly connected with the lateral parietal connections (R-ASG; supramarginal gyrus (SMG), 14 contacts and intraparietal sulcus (IPS), 2 contacts). The L-ASG however had a poor connection to the left SMG (WM 1.7, 6 contacts) and no electrodes sampling the IPS.

Other regions

The L-ASG strongly connected to the ipsilateral claustrum (1 contact), This was not sampled on the right.

Contralateral connections:

Contralateral connections from the R-ASG were to the left IFG PT (5 contacts), claustrum (1 contact), lateral orbitofrontal region (5 contacts) and the left anterior cingulate (8 contacts). Of note, the right anterior cingulate also had contralateral connectivity via the L-ASG but less so (WM 2, 6 contacts)

The L-ASG had a very strong contralateral connection to the right anterior precuneus (1 contact). Contralateral strong connectivity was also seen in the angular gyrus (2 contacts), frontal operculum (5 contacts), hippocampal head (3 contacts), inferior frontal sulcus (IFS) and the STS (2 electrodes each).

In comparison, the R-ASG also showed a moderately strong connection to the opposite frontal operculum, however, not clearly as strong (WM 2.4 but with a SD of 0.8 in 14 electrodes). The contralateral connection from R-ASG to left hippocampal head was also seen to be present but modest (8 contacts, WM 2). The R-ASG lacked sampling in the contralateral (left) precuneus and angular gyrus.

Intra and inter-insula connectivity:

R-ASG was strongly connected to the ipsilateral PSG (8 contacts). Contralateral connections were modest.

The L-ASG is most strongly connected to the ipsilateral ALG (WM 4, 3 electrodes), MSG (WM 3.2, 5 contacts), PLG (WM 3, 2 contacts) and shows strong contralateral connectivity to the R-ASG (WM 3.2, 5 contacts) and R-PSG (WM 3, 3 contacts).

The Middle Short Gyrus (MSG)

Four patients had CCEPs performed in the R-MSG, with one patient having 2 pairs of electrodes placed orthogonally, giving a total of 5 stimulated CCEP pairs. In total, 218 grey matter electrodes were analyzed in 40 anatomical regions. This was divided into 149 electrode contacts in the right hemisphere across 21 anatomical sites and 69 contacts in the left hemisphere representing 19 individual anatomical areas.

Five pairs of L-MSG CCEPs were tested across 5 patients. In total, 538 electrode contacts were analyzed from 78 regions of the brain. 92 contacts were placed in the right hemisphere across 21 anatomical regions and 446 contacts in the left hemisphere across 57 areas.

Figures 3 and 4 represent the right and left MSG.

Fig. 3.

Right MSG

Fig. 4.

Left MSG

Ipsilateral connections:

Frontal connections:

Both MSG were strongly connected to their respective frontal operculae (R-MSG: 8 contacts and L-MSG 22 contacts).

Differences in connectivity were seen in the following connections:

Anterior Cingulate (AC)-The L-MSG was strongly connected to the AC (6 contacts).

Orbitofrontal regions-the R-MSG was strongly connected to the right mesial to lateral orbitofrontal regions (8 contacts in total). The L-MSG had a descending ipsilateral connectivity strength from mesial (WM 2.7, SD 1, 11 electrodes) to lateral (WM 2, 3 contacts) and unknown contralateral orbitofrontal connection.

Gyrus rectus and IFG- the L-MSG was strongly connected to the following areas; Gyrus rectus (6 contacts), IFG- PO & PT (3 and 6 contacts respectively). On contrast, the R-MSG was not as robustly connected to the ipsilateral IFG PO (WM 2.7, SD 1.3, 7 contacts) and gyrus rectus (WM 2.6, SD 1.3, 4 contacts).

Other- The R-MSG also was strongly connected to the ipsilateral IFS (only 1 contact) and SFS (4 contacts). The status of these connections from the left MSG is unknown. The L-MSG strongly connected to the left motor cortex (13 contacts), which was not sampled on the right.

Temporal connections

Both MSG connected strongly to the temporal poles (R-MSG 8 contacts, L-MSG 4 contacts), and middle temporal gyrus (MTG) (R-MSG 6 contacts and L-MSG 27 contacts).

The R-MSG had strong connections to the hippocampal head (6 contacts, SD 0), whereas the left was weaker (WM 2.6, SD 0.5, 7 contacts) although the connection to the hippocampal tail and fimbriae were stronger (WM 4 and 3, SD 0 respectively).

Furthermore, L-MSG stimulation showed strong responses in the ipsilateral temporal operculum (planum polare and temporale 12 and 15 contacts respectively), the STG (10 contacts), ITS (5 contacts), uncus (3 contacts) superior temporal sulcus (9 contacts).

These areas were not sampled on the right.

Parietal connections

The L-MSG also had a strong bilateral connection to the superior parietal lobules, whereas the R-MSG was only modestly connected to its own side (WM 2, SD1, 6 electrodes).

The L-MSG strongly connected the ipsilateral primary sensory cortex (5 contacts). This was not represented on the right.

Other regions:

L-MSG showed strong connections to the subcortical structures (globus pallidus and putamen) and to both (ipsilateral and contralateral) claustra. The connectivity of the R-MSG to these areas is unknown.

Contralateral connections:

Differences in frontal lobe connectivity were seen in both MSG as follows: The L-MSG also showed a strong connection to the right frontal operculum (WM 3, SD 0, 3 contacts) and to the right IFG PO (WM 2.8, SD 0.98, 5 contacts) although this was not mirrored from the right (R-MSG to left FO WM 1, SD 0, 3 contacts and IFG PO WM 2,SD 0, 3 contacts).

The R-MSG was seen to strongly connect the left AC (2 contacts), but a poor connection ipsilaterally (WM 2.2, SD 0.6, 9 contacts). In contrast, the L-MSG had a very weak connection to the right AC (WM 1, SD 0, 3 contacts). The R-MSG also projected to the whole left orbitofrontal region (6 contacts mesial to lateral) and to the gyrus rectus (WM 3, 4 electrodes). A stronger connection to the left MFG (WM 3, SD0, 5 contacts) was seen from the R-MSG, than ipsilaterally (WM 2.9, SD 0.8, 16 electrodes).

Contralateral connections to the left MTG from the R-MSG were also significant (3 electrodes).

As mention, the L-MSG also had strong connectivity to the contralateral superior parietal lobule and claustrum.

Intra and inter-insula connectivity:

R-MSG was strong connected with the ipsilateral PSG (WM= 4, 4 contacts).

L-MSG showed strong connections (WM 3–4) in the ipsilateral ALG (4 contacts), MSG (11 contacts), PSG (2 contacts), PLG (12 contacts). Strong contralateral connections were seen in the right MSG (1 contact), and PSG (1 contact).

The Posterior Short Gyrus (PSG)

3 patients had CCEPs stimulated from the R-PSG. In total 253 grey matter electrodes were tested from 46 locations in the brain. 202 electrodes were found in the right hemisphere, representing 36 distinct areas. Stimulations of the R-PSG to 51 electrodes regions in the left hemisphere were present, representing 10 distinct anatomical sites. In the L-PSG, 3 pairs of CCEPs across 3 patients were recorded, spanning 252 contacts in 48 brain regions. 57 electrode contacts had been placed in the right hemisphere spanning 13 anatomical regions, while 195 electrodes where place in the left hemisphere across 35 anatomical areas.

Figures 5 and 6 represent connections from both PSG.

Fig. 5.

Right PSG

Fig. 6.

Left PSG

Ipsilateral connections:

Frontal connections:

Both PSG had strong connectivity to the frontal operculum (R-PSG WM 3.75, 20 electrodes, L-PSG WM 4, 17 electrodes) and the mesial SFG (R-PSG WM 3, 2 contacts; L-PSG WM 3, 4 contacts).

Differences between the PSG included the following areas:

Anterior Cingulate (AC)-The R-PSG was strongly connected to the right AC (2 contacts), whereas the left AC was only moderately well connected by the left PSG (WM 2, SD 0, 2 contacts).

Orbitofrontal gyrus-the R-PSG strongly connected to the mesial orbitofrontal gyrus (2 contacts), which was weaker on the left (WM 2, SD 0, 8 electrodes)

L-PSG to paracentral lobule (5 contacts) and left subcentral gyrus (2 contacts) was strong. The connection of R-PSG to right subcentral gyrus was present but weaker (WM 2, 2 contacts) and unknown for the paracentral lobule.

Temporal connections:

The temporal operculum is very highly connected by the PSG on both sides (Heschl’s gyrus: R-PSG WM 4, 4 contacts; L-PSG WM 3, 6 contacts. Planum temporale: R-PSG WM 4, 16 contacts; L-PSG 3.25, 16 contacts and planum polare: R-PSG WM 3, 5 contacts and L-PSG WM 4, 5 contacts).

The mesial temporal structures comprising the amygdala, hippocampus and mesial temporal pole showed strong efferents from the R-PSG (all WM 3, 3 contacts each). The L-PSG also had strong links to the hippocampus (WM 4, 2 contacts) and uncus (WM 3, 2 contacts) but only a modest connection to the amygdala (WM 2, 2 contacts). The mesial temporal pole region on the left was not represented.

The temporal neocortical areas of the STG and STS were strongly connected by the R-PSG (WM 3.3 and 4 and contacts 15 and 1 respectively) and the STG and MTG by the L-PSG (WM 3.1 and 3 and 7contacts each respectively). In contrast, the R-PSG to ipsilateral MTG was however modestly connected (WM 1.8, SD 0.8, 11 electrodes)

Parietal connections:

The R-PSG connected strongly to the ipsilateral SMG (2 contacts). The connection for L-PSG was not sampled. The L-PSG had a very strong ipsilateral connection to the ipsilateral parietal operculum (WM 4, 16 contacts), whereas the right PSG connection was not as strong (WM 2.6, 19 electrodes)

Other regions:

The R-PSG was strongly linked to the lateral occipital gyrus (7 contacts). The left was unknown.

Contralateral connections:

The R-PSG was highly connected to the contralateral (left) parietal operculum (PO) (WM 4, 2 contacts), whereas the L-PSG had a modest connection only to the right PO (WM 2, 8 contacts, SD 0). Conversely, the L-PSG had a strong connection to the right (contralateral) FO (WM 3, 5 contacts), whereas the right PSG to the left FO was weaker (WM 2, 9 contacts).

Both the PSG’s were well connected to the contralateral STG, although the right was stronger (R-PSG to left STG-WM 3, 8 contacts and L-PSG to right STG- WM 2.7, 7 contacts).

Intra and inter-insula connectivity:

Stimulation of the R-PSG resulted in the strongest connectivity (WM= 4) in the ipsilateral insula contacts comprising the ASG, ALG and PLG. A strong connection was also seen to the left PLG (5 contacts)

The L-PSG connectivity was mainly to ipsilateral ALG. Only moderate connections (WM 2) were seen to the right ASG, PLG and PSG.

The Anterior Long Gyrus (ALG)

Four pairs of electrodes, from 4 patients had CCEP stimulation from the R-ALG. 304 electrode contacts were studied from 47 anatomical regions. 292 electrode contacts highlighted 42 separate anatomical areas in the right hemisphere, while 12 electrode contacts were placed in the left hemisphere across 5 anatomical regions.

Five pairs of L-ALG CCEP responses were acquired from 5 patients, spanning 559 electrodes from 68 regions of the brain. 70 electrodes were implanted in the right hemisphere across 17 anatomical areas and 487 in the left hemisphere across 51 anatomical regions.

Figures 7 and 8 show the connectivity of both ALG

Fig. 7.

Right ALG

Fig. 8.

Left ALG

Ipsilateral connections:

Frontal connections:

Both ALG were strongly linked to the frontal opercular regions (R-ALG WM 4, 10 contacts; L-ALG WM 3.6, 15 electrodes).

The L-ALG was highly linked to the ipsilateral gyrus rectus (WM 3, 16 contacts), the precentral gyrus (WM 3.6, 13 contacts) and sulcus (WM 3 but only 1 contact). The R-ALG however, only showed a weaker connectivity to these regions (right Gyrus Rectus WM 1.7, SD 0.9, 6 contacts and right pre-central gyrus WM 2, SD 0, 6 electrodes) R-ALG strongly connected to the ipsilateral IFG pars orbitalis (POrb) (5 contacts), the subcentral gyrus (3 contacts) and mesial frontal pole (3 contacts). On the left, the connection to mesial frontal pole was much weaker (WM 1.8, SD 0.4, 13 electrodes) and those to the subcentral gyrus and IFG POrb were unknown.

Temporal connections:

Both ALG had strong ipsilateral connections to mesial temporal areas including the uncus (R-ALG WM 4, 1 contact; L-ALG WM 3.2 6 contacts), amygdala (R-ALG WM 3, 7 contacts; L-ALG WM 3.6 10 contacts) and parahippocampal gyrus (R-ALG WM 3, 3 contacts; L-ALG WM 3.4 and 8 contacts). L-ALG additionally revealed major efferents to the collateral sulcus (WM 4, 2 contacts) and fimbria (WM 3, 2 contacts) although these were not sampled from the right.

Lateral temporal contacts showed a difference between the two regions. Firstly, the L-ALG showed significant efferents to the lateral temporal pole (WM 3, 6 contacts) and the STG (WM 3.3, 11 contacts). Conversely, the R-ALG displayed a slightly less strong connection to STG (WM 2.9, 16 contacts) and very weak connections to the lateral temporal pole (WM 1, 4 contacts). The R-ALG showed strong connections to the STS (WM 4, 2 contacts), which was weaker from the L-ALG (WM 2, 2 contacts).

Both ALG were also highly connected to their respective temporal opercular regions (right ALG- planum polare and temporale (WM 3.2 and 4 and 2 and 4 electrodes respectively. L-ALG- planum temporale and polare (WM 3.2 and 3, 10 and 12 electrodes respectively). It is worth noting that the L-ALG strongly connected to Heschl’s gyrus (WM 3, 14 contacts) whereas the R-ALG connection to ipsilateral Heschl’s was weaker (WM 1.8, SD 0.4, 5 contacts).

Parietal connections:

Both ALG were highly connected to their corresponding parietal operculum (R-ALG-WM 3.6, 11 contacts; L-ALG WM 4, 27 contacts).

The R-ALG connected strongly to the ipsilateral primary sensory cortex (4 contacts). Interestingly, there was almost no connection seen from the L-ALG to this area (WM 1, SD 0, 2 contacts)

The L-ALG showed strong connectivity to the ipsilateral posterior precuneus (4 contacts). The R-ALG was also connected to precuneus (anterior) but moderately so (WM 2.4, SD 0.5, 5 electrodes)

Other areas:

The L-ALG was strongly connected to the ipsilateral claustrum and globus pallidus. These connections were unknown from the right.

Contralateral connections:

R-ALG connected to the left mesial orbitofrontal region and L-ALG to the right inferior frontal sulcus (both areas single contacts). The left ALG was also strongly connected to the right ASG (WM 3, 2 contacts).

Intra and inter-insula connectivity

CCEP analysis in the R-ALG revealed highly connected areas in the right (10 contacts). L-ALG connections were best in ipsilateral ASG (WM 4, 3 contacts), MSG (WM 3.8, 10 contacts) and PSG (WM 3, 3 contacts).

The Posterior Long Gyrus (PLG)

Six pairs of CCEPs from 6 patients were recorded from the R-PLG. In total, 556 contacts from 64 anatomical regions were analyzed. 515 electrode contacts were located in the right hemisphere in 52 areas and 41 electrodes in the left hemisphere in 12 anatomical regions.

Six pairs of L-PLG CCEPs were performed in 5 patients, spanning 648 electrodes over 77 regions of the brain. 70 electrodes in the right hemisphere in 14 anatomical areas and 578 electrodes were located in the left hemisphere across 63 anatomical areas. Figures 9 and 10 outline the full connectivity profiles from both these regions.

Fig. 9.

Right PLG

Ipsilateral connections:

Frontal connections:

Both PLG demonstrated strong ipsilateral connections to the primary motor region (R-PLG WM 3.6, 7 contacts to the right precentral gyrus. L-PLG WM 3, 4 contacts to the precentral sulcus. Of note, no precentral sulcus contact was available on the right, and the precentral gyrus contact on the left showed a weaker connection (WM 2.2, SD 0.6, 18 contacts).

The R-PLG also had a strong connection to the frontal operculum (WM 4, 13 contacts), although the left PLG wasn’t as strongly connected (WM 2, SD 1.0, 25 contacts).

The L-PLG was well connected to the IFG-P Operc and IFG-PT (WM 3.4 and 3.2 and 8 and 10 contacts respectively) with poor connectivity to IFG POrb (WM 1, 3 contacts). In contrast, the R-PLG showed strong connectivity with IFG-POrb (WM 3.8, 14 electrodes), moderate connectivity with IFG-PO (WM 2.3, SD 0.7, 25 electrodes) and very poor connectivity with IFG PT (WM 1, SD 0, 6 electrodes).

The R-PLG was well connected to the ipsilateral IFS (WM 3, 2 contacts), but the L-PLG was a weak connection in only 1 representative contact (WM 2)

Temporal connections:

Both PLG shared similar qualities being highly connected to the temporal operculum (R-ALG- WM 3.8–4, Heschl’s gyrus (9 contacts), planum polare and temporale (10 and 20 contacts respectively)); L-ALG- WM 3.2–4, planum temporale (21 contacts), Heschl’s gyrus (12 contacts) and planum polare (17 contacts)

Both regions also demonstrated links to certain mesial temporal areas but to varying degrees. Strong links were seen from the R-PLG to the ipsilateral amygdala (WM 4, 10 contacts), uncus (WM 4, 1 contact), parahippocampal gyrus (WM 3.8, 4 contacts), entorhinal cortex (WM 3, 1 contact) and the hippocampus (WM 3.3, head and tail 23 contacts total). However, the L-PLG only showed a strong connection to the tail of hippocampus (WM 3.5, 8 contacts) and the more anterior mesial temporal connections were weaker (hippocampal head (WM 2.5, 4 contacts, SD 0.8), amygdala (WM 1.8, 13 contacts), uncus (WM 1.5, 8 contacts), parahippocampal gyrus (WM 1, 1 contact)). Both PLG also strongly connected to the ipsilateral STG (R-PLG WM 3., L-PLG WM 3,15 contacts each). The R-PLG also highlighted strong efferents to the STS (WM 3, 15 contacts), while the left side was less well connected to the this region (WM 2, 9 contacts) The L-PLG strongly connected with the temporal pole (WM 4, 16 contacts in total, stronger connections lateral to mesial), ITG and ITS (WM 3 and 4, 9 and 5 contacts respectively). In comparison, connection to the ITG from the R-PLG was modest (WM 2.1, 21 contacts) and a poor to the temporal pole (WM 2 for mesial part and WM 1 for the lateral part in total of 4 contacts)

Parietal connections:

Both PLG were also highly connected to the parietal opercular regions (R-PLG WM 3.2, 9 contacts and L-PLG WM 3.2, 27 contacts).

The R-PLG was strongly connected to the ipsilateral sensory cortex (WM 3, 7 contacts). The L-PLG showed strong connectivity to the left postcentral sulcus (WM 3, 3 contacts) but a weaker connection to the postcentral gyrus (WM 2.2, 22 contacts,)

The L-PLG was strongly connected to the supramarginal gyrus (WM 2.6, 25 contacts), whereas the right PLG was moderately well connected (WM 2.6, SD 1.1, 19 electrodes). Connectivity of the L-PLG to the inferior precuneus was strong (WM 3, SD 0, 4 electrodes) but weaker from the R-PLG (WM 2, 2 contacts)

Other regions

Both PLG were also highly connected to the claustrum (WM 4, 2 contacts from right and 4 from the left)

The L-PLG had very strong bonds (WM4) with the subcortical areas (globus pallidus and putamen), representation of these areas on the right was absent.

The left PLG connected strongly to the paracentral lobule (WM 3.1, 11 contacts), whilst the right PLG had a weaker connection to the right paracentral lobule (WM 2, 6 contacts).

Contralateral connections:

The R-PLG was the highly connected to the contralateral lingula (WM 4, 2 contacts, SD 0), the temporal regions (collateral sulcus (WM3, 4 contacts), ITG (WM 3, 3 contacts), temporal pole (WM 3, 2 contacts)), including the temporal operculum (planum temporale-WM 3, 5 contacts). Contralateral connections from the L-PLG to the right planum temporale, STG and STS were weak.

Interestingly, the left PLG had a bilateral projection to the frontal opercular regions with an equally connected moderate value (WM 2).

Intra and inter-insula connectivity:

Strong intra-insula contacts from the L-PLG were seen in the ipsilateral ALG, MSG and PSG. Ipsilateral intra-insula connections from the R-PLG, were weaker and included the right ASG (WM 2.6, 9 contacts) and the ALG (WM 2, 1 contact). Contralateral L-PLG to the right MSG was present but weak (WM 1).

Contralateral insula connections from the right were not sampled.

DISCUSSION

CCEPs of the individual gyri in the human insula in both hemispheres, highlight the extensive and complex networks arising from each sub-region of this cortical area. These efferent connections explain why the insula is a major integrative hub and so highly involved in a large number of important functions.

Language function and the Insula

The insula is increasingly being recognized as having a major role in the language network [33–36]. Cortical regions involved in language function are complex and involve two major modalities (i) regions for speech articulation and motor control-including Broca’s region (IFG pars opercularis and triangularis) and the primary motor cortex and (ii) language association areas, comprising widespread cortical regions including the temporal pole, primary auditory cortex, fusiform gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, angular gyrus and the superior, middle and basal temporal gyri [37] and the SMA [38].

Our work shows strong connectivity to both language motor and association areas, from the dominant insula. What is striking is the finding of maximal language efferents from each opposing pole of the insula, meaning that the ASG sends long efferents to the posterior brains regions and the PLG conversely, connects more anterior brain regions. The ASG and PLG both relay connections to the basal temporal language areas (ITG and fusiform) and parietal language areas (angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus).

Speech articulation and motor control have been shown to involve the precentral gyrus of the insula [33,39–43] as well as the recognized inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s) and primary motor area. Cortical stimulation studies in the insula, resulting in speech disturbances, have also helped confirm this [44–45]. The obtained CCEP results provide insight into this mechanism, showing that the left ASG and MSG are strongly connected with IFG-pars opercularis and with the primary motor cortex. However, we further report involvement of the posterior insula. The ALG also connects to the primary motor cortex and along with the PLG, both are strongly linked to IFG pars opercularis, and pars triangularis. These regions also show strong connectivity to the primary auditory cortex, a key language association area that modulates functional connectivity during motor speech [46]. This posterior insula-auditory-speech motor network that we describe, is implicated in studies of deaf individuals, utilizing lip-reading and articulatory-based cues, which show grey matter hypertrophy in the posterior insula [47].

The insula PSG also shows a similar connectivity pattern. Although it is well connected to the auditory cortex and Broca’s areas, it is conversely not strongly connected to the primary motor cortex. This may explain the recent study, arguing against the specific role of the precentral gyrus of the insula in articulation [48]. Rather it suggests that the role is in fact a modulation of articulation in combination with the IFG pars operculum, a role that is also shared by the SMA [38]. Our own work shows that the PSG is strongly connected to these regions too.

Language association regions are also highly connected by the dominant insula, with the lateral temporal language areas receiving strong projections from the importation of the insula namely MSG, PSG and ALG. The temporal pole is also highly connected from both anterior and posterior insula regions (ASG, MSG, ALG and PLG), which correlates well with primate studies, where these strong connections are attributed to a limbic integrating system for complex, preprocessed visual and auditory information with the insula [16].

Stimulation findings have previously reported speech disturbances arising from both insula, particularly during stimulation of the MSG [45]. Our study may explain these findings to some degree given that the non-dominant insula projects to contralateral language areas (namely R-ASG to left pars triangularis; R-MSG to left MTG, R-PSG to left STG and R-PLG to the left temporal pole). We observe that while the right MSG has moderate connections to left language networks, it is also highly connected from the left MSG. The right anterior insula has shown to be an important mediator in speech and language function [36] but also strongly activated during non-lyrical singing (non-lyrical tune) [49]. While we did not find strong intra-insular connectivity from the right to left MSG, the right MSG was still fairly well connected to the ipsilateral Heschel’s gyrus and primary motor cortex. We hypothesis that in situations such as non-lyrical singing, the left MSG may enhance the right, or even suppress the left, in order to engage non-verbal language function.

We report that the intra-insular connectivity of the dominant insula appears to have a “closed-loop” like connectivity. The anterior insula structures are highly connected in a “downstream-upstream” gradient (ASG to MSG, ALG, PLG; MSG to PSG, ALG, PLG; PSG to ALG, PLG; ALG to all and PLG to ALG, PSG, MSG). It remains to be elucidated how and if such connectivity has a role to play in language function.

Sensation: Pain, Interceptive awareness and somatosensory afferents

Multimodal information processing networks across sensorimotor, emotional and homeostatic domains are increasingly being attributed to the insula [50–51]. Although some studies suggest an asymmetry in function, with the right/non-dominant insula being attributed to negative affect, hunger survival, avoidance behaviors [52], cardiac control [53] and also in pain [54], such lateralization of valence is not so clearly defined at present [55–56]. Our own study, however, reveals an asymmetry in connectivity. The right insula, at least for somatosensory function, has more ipsilateral and contralateral connections than the left. This may be due to earlier development of the right hemisphere, making developmental connections more complete [50], especially in the context of patients with epilepsy, where pathological activity may impair plasticity, thus our results may be bias with respect to lateralization.

Sensory integration appears to follow a hierarchy within the insula in a “bottom-up”/posterior-to-anterior axis, whereby sensory inputs to the posterior insula are propagated to the mid-insula region for homeostatic processing and then onto the anterior regions for saliency processing [54,57–60]. Our research supports the existence of this axis to a degree; especially as both posterior insula regions (ALG and PLG) are highly connected to the ipsilateral anterior gyri. We also demonstrate that the left posterior intra-insula contacts are more widely connected to their ipsilateral short gyri than on the right. The left ALG is also strongly connected to both the ASG. These additional connections from the left may provide an explanation as to why the left hemisphere shows dominance for positive emotional stimuli in the anterior and mid insula regions and during the perception of emotion in others, despite both posterior insula regions being activated in both cases [54]. Having developed later in embryological terms, the left insula may be responsible for higher cognitive situational assessment, and thus support the notion that the right insula is a default network concerned mainly with “negative” emotional processing (hunger, avoidance, pain) to ensure species survival [53]. Further evidence comes from the findings that the right anterior insula becomes activated by emotionally aversive stimuli and harm avoidance behavior [61] and that dysfunction of this system may be the key in everyday anxiety disorders [62].

Pain processing is also a role ascribed to the insula along with the anterior cingulate region (AC), the parietal operculum (SII), the primary sensory cortex (S1) and the limbic structures including the amygdala, hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex and precuneus [63–65]. Of these regions, the AC is thought to be more specific to pain processing [66–68] compared to SII, where historical stimulation failed to produce nociceptive experiences [69].

Specifically, the MSG has been implicated in pain processing with stimulation studies [70]. The CCEP studies support this finding given that both MSG are highly connected to the left AC with additional cross connectivity from the right ASG. The right AC appears to be less well connected by the insula receiving inputs mainly from the right PSG. Connectivity of the right anterior insula to the AC has been shown to be important in bladder control and urgency [71]. Another CCEP study did not find evidence of connections from the insula to anterior cingulate [29].

Insula to cingulate connections involve Von Economo neuronal (VENs) networks, specialized neurons present in the anterior cingulate and frontoinsular cortices [72], which are more abundant on the right side [73]. If we extend our findings, of the dual efferent innervation of the left AC, further afield, in neurology, it may provide addition insight into the neurological illness of fronto-temporal dementia (FTD). In this disorder, decreased VEN densities are a pathological marker [74] but only patients with right-sided FTD present with behavioural disturbances [75]. This is presumably since the right AC only receives a paucity of ipsilateral insula connections, resulting in a frontal disconnection syndrome, whereas the left is relatively protected by the benefit of bilateral innervation.

The right and left MSG and PSG also show strong connections to mesial temporal and frontal limbic areas as well as SI and SII as well as the novel finding of the right PSG connecting to the contralateral SII, which supports the hypothesis that the mid-posterior insula is in fact a multimodal homeostatic or interoceptive area [76].

We highlight the strong connectivity of both posterior insula regions to S1 and SII, confirming their role in the sensory network. This was also demonstrated through fMRI [77]. Significant connectivity of the posterior insula regions to their respective amygdala and hippocampi were seen, but with additional right posterior insula cross-connections to the contralateral left orbitofrontal region. Studies in anger responses have shown increased activity in the right posterior insula and STG and to a lesser degree the left posterior insula and hippocampus [78].

We hypothesize that the posterior insula may itself have independent emotional sensory processing capabilities rather just a relay to the anterior insula for processing.

The precuneus has also shown to be part of the sensory network, especially in visuo-tactile texture matching in fMRI studies in healthy volunteers [79]. The precuneus and mesial limbic regions are connected via the insula, although only one study has demonstrated this in humans [80]. Our research demonstrates this connection of the left posterior insula (ALG and PLG) and left ASG being strongly connected to the ipsilateral precuneus and also the mesial limbic networks.

Interoceptive awareness (conscious awareness of inner bodily signals) [51] is mediated by the right anterior insula to higher-order areas of visceral representation such as the orbitofrontal cortex [81–82]. The CCEP data highlight the right MSG and PSG efferents to the ipsilateral orbitofrontal cortex and the novel finding that the right anterior (ASG) and posterior insula (ALG) are also highly integrated with the left (contralateral) orbitofrontal region. The left insula is not as well connected to either orbitofrontal area and this may explain why previous CCEP studies may have failed to show insula-orbitofrontal connectivity [29] or that only the left ASG has some connection to the orbitofrontal regions [83].

The insula-orbitofrontal networks are attributed to processing the final evaluation of reward or punishment implicated by a certain stimuli [84]. An example of this network at play comes from the sensation of taste. A recent fMRI study implicated the left MSG and ALG as the determinants of pleasantness of taste, and the right ALG and PLG being involved in taste concentration processing, in a male-only cohort [85]. Our connectivity study confirmed the findings of insula-orbitofrontal connectivity to be present, but weak, from the left and absent from the right. However, a partial explanation may be due to our cases being of mixed sex.

Vision

Few studies in the human insula have reported direct links between the visual cortex and insula. Recently, high-resolution tractography studies have reported, for the first time in humans, ipsilateral connections between the insula lobe and the visual cortex as well as parietal and temporal visual association areas (supramarginal and angular gyri, fusiform gyrus, cuneus and precuneus) [80]. The insula, with respect to visual function, is thought to act as a cross modal cortical integrator for stimulus perception [86–87] as well as visual consciousness [88]. The latter also requires parietal integration (precuneus and lateral parietal cortex) as part of the default mode network [89].

Our study supports such findings and adds a novel dimension to the literature. Firstly, it appears that connectivity from the left insula, to visual association areas is more ubiquitous, although this may be due to limited sampling between insula and occipital regions within our database. The ASG on both sides were found to be more highly connected to structures implicated in the ventral visual stream [90], including the fusiform gyrus (left ASG), the inferior temporal gyrus (left ASG), the angular gyrus (both) and the intra-parietal sulcus and supra-marginal gyrus (right ASG respectively). This may explain why dysfunction of the anterior insula has recently been implicated in migraine with aura [91]. The right posterior short gyrus also shows strong connectivity between the lateral occipital cortex and supra-marginal gyrus with respect to the visual integration from the right insula.

One finding, unreported to date, is the strong contralateral connectivity from the right posterior long gyrus to the left lingula and inferior temporal gyrus, with weak ipsilateral connections to these same areas. These findings may provide clues in the specific role of the right PLG in visuospatial navigation, namely that activation of visual cortex and motion-sensitive areas (such as the inferior temporal gyrus) are associated with a deactivation of the right posterior insula [92], whereas in the blind, the opposite is true and imagined locomotion activates the posterior insula [93], which may act as an alternative sensorimotor region when vision is impaired or limited (e.g. navigating at night)

Hearing:

The insula is an integral part of the auditory system, along with the primary auditory cortex (Heschl’s Gyrus), the planum temporale and lateral superior temporal gyrus [94]. Connectivity studies in monkeys support the involvement of the posterior insula as an important auditory region [95]. Our CCEP findings confirm strong connections to Heschl’s gyrus from the right (PSG and PLG) and left insula (PSG, ALG, PLG). Interestingly, the right ALG was not well connected to the ipsilateral Heschl’s and left sided insula connections appeared more extensive when compared with the right. Planum temporale was strongly connected ipsilaterally from both mid-posterior insula regions (PSG, ALG and PLG on the right and MSG, PSG, ALG and PLG) and the lateral superior temporal gyrus as similarly connected by the posterior long gyri on both sides and additionally by the posterior short gyrus on the left. Impairment of these mid-posterior insula connections has previously been implicated in music aversion in dementia [96].

A novel finding in our CCEP research is the finding of connectivity from both PLG to the contralateral Heschl’s, in both hemispheres, along with MSG from the right and PSG from the left. This may explain the reported findings of contralateral ear hypoacusis during posterior insula stimulation [64].

Furthermore, the anterior insula showed weaker connections to Heschl’s but stronger connections to secondary auditory areas, suggesting they may have an integrative role in auditory processing, as previous suggested in stroke studies of the insula [97].

Intra and inter-insula connectivity:

Connectivity between the two insula lobes has been reported to occur from both anterior and posterior regions in animal studies [98–99] but is sparsely reported in humans. Using CCEPs one study in humans, could not find proof of connectivity between the posterior insula regions [29]. In another single case report, utilizing latency as a connectivity marker, the anterior insula regions on both sides were found to be linked (right PSG to left PSG and left MSG and left PSG to right PSG) [28]. The same study could not however confirm contralateral connectivity from the posterior insula.

Our own results highlight strong cross-connectivity mainly from the left ASG, MSG and ALG and only moderate connections from the right ASG and PSG. The PSG appear to be the major hubs between anterior and posterior insula regions within each respective insula. Additionally, the polar opposites of each insula do show connectivity (ASG to PLG and vice versa) although this is only a moderately strong connection within the right insula but a stronger connection from the left.

Limbic connectivity and epilepsy

Surgical failure in patients diagnosed with temporal lobe epilepsy is increasingly being attributed to a failure of recognition of the insula as an epileptogenic zone due to the significant connections to the mesial temporal regions [25,69,100]. Our own findings confirm the significant connections to the mesial temporal structures from all gyri of the right insula. The left insula similarly showed full connectivity to the hippocampus but the amygdala received connections from the ASG, PSG and ALG only. The left ASG was also strongly connected to the right hippocampus. This may explain why patients with left sided temporal lobe epilepsy exhibit greater white matter damage [101], especially as both hippocampi are highly connected to their ipsilateral insula [6].

Structural imaging studies have shown strong connectivity of the amygdala and temporal pole by the anterior insula in the human and macaque monkey [14,19,20,101]. Conversely, prior CCEP studies in humans showed the reverse situation with connectivity of the amygdala with posterior but not anterior insula connections [29]. Similarly, this study showed hippocampal connections from all the insula except PSG. In our results, the right temporal pole was connected by the right ASG and MSG while the left temporal pole received connections from the ASG, MSG, ALG and PLG. Cross connectivity from the right PLG was also seen to the left temporal pole. The strong connectivity to this region from both insula may explain why it is also implicated in language and naming [102].

Vestibular

The insula has been implicated in vestibular function, particularly the right insula. Some studies have implicated both anterior and posterior insula regions [103], whereas others have implicated the poster-superior part in conjunction with the adjacent parietal opercular region, termed the parieto-insula vestibular cortex [104–105]. Cortical stimulation studies in epilepsy patients undergoing SEEG have confirmed vestibular sensations in the posterior insula [106]. While the extended vestibular network is still not well established [105], cortical stimulation studies in humans have also implicated the superior and middle temporal gyri, inferior parietal lobule, intraparietal sulcus and angular gyrus [107–110]. This multi-lobar involvement has also been confirmed by animal studies [111–112]. Neurons comprising the vestibular cortex are multisensory incorporating optokinetic and somatosensory stimuli [113].

Our results show connectivity to the vestibular network mainly from the right insula with bilateral connectivity from the right anterior insula (ASG, MSG and PSG). What is particularly pertinent is the finding that both posterior long gyri are well connected to the STG and parietal opercular regions and that it is the right PSG, which connects the STG and parietal opercular regions on both sides. Vestibular stimulation, during fMRI, highlighted increased neural activity in the posterior insula and STG [114], but conversely during visual stimulation of a rotating stimulus bilateral insula blood flow decrease was observed on PET [115]. The right PSG also has contralateral connections to the left PLG, which in turn has strong connections to most of the left insula. As the PSG has been shown to have afferents from all types of vestibular receptors [116], we propose that it may be a major hub for sensory switching reciprocal inhibition, allowing for a change in the dominant sensory system, depending on the prevailing sensory mode.

CONCLUSION

CCEPs of both human insulae efferents confirm this structure to be a major multi-modal network hub within the cerebral cortex. The sheer amount of connections explains the complex neurophysiological function and that it is a key region involved in both functional and effective connectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under award R01NS089212. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

No part of the study procedures was pre-registered prior to the research being conducted.

MATLAB codes that were used to process CCEPs, raw post processed data and stimulation numbers are provided as excel spreadsheets (https://osf.io/vbu39/quickfiles). In addition, the conditions of our ethics approval do not permit public archiving of anonymised study data. Readers seeking access to the raw stimulation EEG data should contact the Epilepsy Centre or the local ethics committee at the Cleveland Clinic, Main Campus, Ohio, USA. Access can be granted only to named individuals in accordance with ethical procedures governing the reuse of sensitive clinical data.

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kirsty Rickett (Library services, University of Queensland), Matthew Woolfe and Mr. Don Murray.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friston KJ (2009) Modalities, modes, and models in functional neuroimaging. Science 326:399–403. 10.1126/science.1174521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sporns O, Tononi G, Kötter R (2005) The human connectome: A structural description of the human brain. PLoS Comput Biol 1:e42 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friston KJ (2011) Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect 1:13–36. 10.1089/brain.2011.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto R, Nair DR, LaPresto E, et al. (2004) Functional connectivity in the human language system: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Brain J Neurol 127:2316–2330. 10.1093/brain/awh246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller CJ, Honey CJ, Mégevand P, et al. (2014) Mapping human brain networks with cortico-cortical evoked potentials. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 10.1098/rstb.2013.0528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Enatsu R, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Bulacio J, et al. (2015) Connections of the limbic network: a corticocortical evoked potentials study. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav 62:20–33. 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto R, Nair DR, LaPresto E, et al. (2007) Functional connectivity in human cortical motor system: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Brain J Neurol 130:181–197. 10.1093/brain/awl257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enatsu R, Piao Z, O’Connor T, et al. (2012) Cortical excitability varies upon ictal onset patterns in neocortical epilepsy: a cortico-cortical evoked potential study. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol 123:252–260. 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lega B, Dionisio S, Flanigan P, et al. (2015) Cortico-cortical evoked potentials for sites of early versus late seizure spread in stereoelectroencephalography. Epilepsy Res 115:17–29. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Türe U, Yaşargil MG, Al-Mefty O, Yaşargil DC (2000) Arteries of the insula. J Neurosurg 92:676–687. 10.3171/jns.2000.92.4.0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanriover N, Rhoton AL, Kawashima M, et al. (2004) Microsurgical anatomy of the insula and the sylvian fissure. J Neurosurg 100:891–922. 10.3171/jns.2004.100.5.0891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Türe U, Yaşargil DC, Al-Mefty O, Yaşargil MG (1999) Topographic anatomy of the insular region. J Neurosurg 90:720–733. 10.3171/jns.1999.90.4.0720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guenot M, Isnard J, Sindou M (2004) Surgical anatomy of the insula. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg 29:265–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Augustine JR (1996) Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 22:229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nieuwenhuys R (2012) The insular cortex: a review. Prog Brain Res 195:123–163. 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesulam M-M, Mufson EJ (1985) The Insula of Reil in Man and Monkey. In: Peters A, Jones EG (eds) Association and Auditory Cortices Springer; US, pp 179–226 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ (1982) Insula of the old world monkey. III: Efferent cortical output and comments on function. J Comp Neurol 212:38–52. 10.1002/cne.902120104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mufson EJ, Mesulam MM (1982) Insula of the old world monkey. II: Afferent cortical input and comments on the claustrum. J Comp Neurol 212:23–37. 10.1002/cne.902120103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cauda F, D’Agata F, Sacco K, et al. (2011) Functional connectivity of the insula in the resting brain. NeuroImage 55:8–23. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerliani L, Thomas RM, Jbabdi S, et al. (2012) Probabilistic tractography recovers a rostrocaudal trajectory of connectivity variability in the human insular cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 33:2005–2034. 10.1002/hbm.21338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomassini V, Jbabdi S, Klein JC, et al. (2007) Diffusion-weighted imaging tractography-based parcellation of the human lateral premotor cortex identifies dorsal and ventral subregions with anatomical and functional specializations. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 27:10259–10269. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2144-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isnard J, Guénot M, Ostrowsky K, et al. (2000) The role of the insular cortex in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 48:614–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryvlin P (2006) Avoid falling into the depths of the insular trap. Epileptic Disord Int Epilepsy J Videotape 8 Suppl 2:S37–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryvlin P, Kahane P (2005) The hidden causes of surgery-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy: extratemporal or temporal plus? Curr Opin Neurol 18:125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen DK, Nguyen DB, Malak R, et al. (2009) Revisiting the role of the insula in refractory partial epilepsy. Epilepsia 50:510–520. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afif A, Minotti L, Kahane P, Hoffmann D (2010b) Anatomofunctional organization of the insular cortex: a study using intracerebral electrical stimulation in epileptic patients. Epilepsia 51:2305–2315. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almashaikhi T, Rheims S, Ostrowsky-Coste K, et al. (2014b) Intrainsular functional connectivity in human. Hum Brain Mapp 35:2779–2788. 10.1002/hbm.22366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lacuey N, Zonjy B, Kahriman ES, et al. (2016) Homotopic reciprocal functional connectivity between anterior human insulae. Brain Struct Funct 221:2695–2701. 10.1007/s00429-015-1065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almashaikhi T, Rheims S, Jung J, et al. (2014a) Functional connectivity of insular efferences. Hum Brain Mapp 35:5279–5294. 10.1002/hbm.22549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merrill DR, Bikson M, Jefferys JG. Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of efficacious and safe protocols. J Neurosci Methods 2005. February 15;141(2):171–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prime D, Rowlands D, O’Keefe S, Dionisio S. Considerations in performing and analyzing the responses of cortico-cortical evoked potentials in stereo-EEG. Epilepsia 2018. January;59(1):16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Vugt MK, Sederberg PB, Kahana MJ (2007) Comparison of spectral analysis methods for characterizing brain oscillations. J Neurosci Methods 162:49–63. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dronkers NF (1996) A new brain region for coordinating speech articulation. Nature 384:159–161. 10.1038/384159a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chee MWL, Soon CS, Lee HL, Pallier C (2004) Left insula activation: a marker for language attainment in bilinguals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15265–15270. 10.1073/pnas.0403703101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guenther FH (2006) Cortical interactions underlying the production of speech sounds. J Commun Disord 39:350–365. 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh A, Duerden EG, Pang EW (2014) The role of the insula in speech and language processing. Brain Lang 135:96–103. 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ardila A, Bernal B, Rosselli M (2016) How Extended Is Wernicke’s Area? Meta-Analytic Connectivity Study of BA20 and Integrative Proposal. Neurosci J 2016:4962562 10.1155/2016/4962562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]