Abstract

Objective:

Platinum compounds have been widely used as a primary treatment for many types of cancer. However, resistance is the major cause of therapeutic failure for patients with metastatic or recurrent disease, thus highlighting the need to identify novel factors driving resistance to Platinum compounds. Metadherin (MTDH, also known as AEG-1 and LYRIC), located in a frequently amplified region of chromosome 8, has been consistently associated with resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, though the precise mechanisms remain incompletely defined.

Methods:

The mRNA of FANCD2 and FANCI was pulled down by RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation. Pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles were prepared using the nanoprecipitation method. Immunocompromised mice bearing patient-derived xenograft tumors were treated with pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles, cisplatin and a combination of the two.

Results:

MTDH, through its recently discovered role as an RNA binding protein, regulates expression of FANCD2 and FANCI, two components of the Fanconi anemia complementation group (FA) that play critical roles in interstrand crosslink damage induced by platinum compounds. Pristimerin, a quinonemethide triterpenoid extract from members of the Celastraceae family used to treat inflammation in traditional Chinese medicine, significantly decreased MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI levels in cancer cells, thereby restoring sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy. Using a patient-derived xenograft model of endometrial cancer, we discovered that treatment with pristimerin in a novel nanoparticle formulation markedly inhibited tumor growth when combined with cisplatin.

Conclusions:

MTDH is involved in post-transcriptional regulation of FANCD2 and FANCI. Pristimerin can increase sensitivity to platinum-based agents in tumors with MTDH overexpression by inhibiting the FA pathway.

Introduction

DNA damaging agents such as platinum compounds have been widely used as a primary treatment for many types of cancer including endometrial cancer, the most frequent gynecologic malignancy[1]. However, resistance is one of the major causes of therapeutic failure for patients with metastatic or recurrent disease, thus highlighting the need to identify novel factors driving resistance to platinum compounds[2]. Of the current genes identified in a frequently amplified region of chromosome 8, metadherin (MTDH, also known as AEG-1 and LYRIC) is a master regulator of cellular functions and is consistently associated with resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic agents, including platinum compounds[3, 4]. Moreover, MTDH amplification is associated with metastasis and poor overall survival in multiple tumor types[5, 6]. MTDH promotes cancer cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in part by activating classical oncogenic pathways, including Ras, myc, NFκB and PI3K/AKT[7].

Recently, our group uncovered a novel function for MTDH as an RNA-binding protein[8]. The association of MTDH with mRNAs has the potential to regulate drug resistance by controlling post-transcriptional processing of multiple proteins. Indeed, two independent studies revealed that MTDH binds to mRNAs that encode several Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway proteins[8, 9]. The FA pathway plays a critical role in DNA repair following interstrand crosslink damage induced by platinum compounds[10]. Studies in patients with mutations in FA pathway proteins demonstrate that, while there is increased risk for cancer development, tumors harboring these mutations respond well to chemotherapy. We hypothesized that down-regulation of the FA pathway by targeting MTDH has the potential to increase sensitivity to platinum-based DNA damaging agents. The objective of this study was to elucidate the role of MTDH on FA pathway regulation and resistance to platinum compounds.

Material and Methods

Analysis of MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI in TCGA data

UCSC Xena browser (https://xena.ucsc.edu) is a public hub with detail online instruction that was used to analyze the correlation of MTDH amplification with MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI expression in endometrial cancer and breast cancer patients in TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas)[11]. Gene expression was determined by comparing transcript-level expression of MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI based on the RNA-sequencing data in the TCGA dataset. MTDH amplification was determined by analyzing copy number variation (CNV) for MTDH after removal of germine CNVs.

Cell line and culture conditions

Hec50 uterine serous carcinoma cells were kindly provided by Dr. Erlio Gurpide in 1991 (New York University). KLE uterine serous carcinoma cells and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection in 2009 (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Hec50 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and penicillin/streptomycin. KLE cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Cell line authentication is performed yearly for all studied lines using the CODIS marker testing. (BioSynthesis, Lewisville, TX). Mycoplasma testing is also performed annually by the University of Iowa DNA Sequencing Core facility. Cells were used no more than 10 passages from thawing to the completion of all experiments.

Western blotting

Cells were scraped into ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS with protease inhibitor) and sonicated three times. Lysates were then centrifuged at 12000 x g for 15 min at 4°C and protein was quantified by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were separated on 10% or 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels then transferred to a nitrocellulose blotting membrane, which was blocked with 5% nonfat milk and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Anti-FANCD2 (1:2000, #NB 200–182) and anti-FANCI (1:500, #ab74332) were obtained from Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA). Anti-RAD51 (1:1000, #8875), anti-LC3B (1:1000, #3868) and anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:1000, #9661) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-β-actin (1:10000, #A5441) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-MTDH (1:250, #517220) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas). Membranes were further incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies at 1: 10000( #7076 and #7074, Cell Signaling Technology) at room temperature for 2 h. Protein bands were detected using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc system, and densitometry was analyzed with BioRad Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For the mice tissue, tissues were dissected on ice, grinded with a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and transferred 20 mg tissue powder to 1.5ml Eppendorf tube in 1ml of ice-cold RIPA buffer and homogenize using electric homogenizer. Lysates were then centrifuged at 12000 x g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected in fresh tube on ice. Protein samples were analyzed with SDS-PAGE gels as described above.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was determined by WST-1 assay. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (1X104 cells per well) then treated with cisplatin (Fresenius Kabi Oncology Ltd, Haryana, India) or the combination of cisplatin with pristimerin in solution (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Cell viability was evaluated using the cell proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured with a micro-plate reader (BioRad). Data were calculated as percent (%) viability relative to untreated control, which was set at 100%.

XTT assay

Cells expressing scrambled sgRNA and multiple MTDH knockout clones were seeded into 96-well plates (1X103 cells per well). Cell growth was monitored by measuring daily over 5 days by XTT assay. XTT (GoldBio, St Louis, MO) solutions were made fresh each day by dissolving XTT in cell culture medium at 1 mg/ml. PMS (Sigma) was made up as a 100 mM solution in phosphate buffered saline and used at a final concentration of 25µM.PMS was added to the XTT solution immediately before use and cells were incubated for 1–2 hours at 37°C. The reaction was placed on a shaker for a short period of time to mix the dye in the solution. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm immediately.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Hec50 cells were seeded on coverslips then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Coverslips were rinsed 3 times with 1ml PBS and incubated with 80% ice-cold methanol for 1 h, followed by permeabilization for 25–30 min with 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells were blocked with 3% BSA then incubated with specific antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Anti-MTDH (1:100, #14065), anti-phospho-histone H2AX (Ser139) (1:400, #9718) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Then, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology) at room temperature for 2 h; nuclei were stained using mounting solution with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Visualization was performed on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope.

Animal Studies

All animal studies were performed under animal protocols #7051085 approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Iowa City, IA). MTDH knockout mice were generated as described previously[12]. Male mice at 20 weeks of age were euthanized and the spleen, brain and liver were removed and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, sonicated in ice-cold RIPA buffer and then protein was extracted for Western blotting. A patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model of endometrial cancer (PDX1) has been previously described [13]. NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) immunodeficient female mice at 8 weeks of age were injected with passage 3 of PDX1 tumor tissue (10mg/100µl medium) into the right flank subcutaneously. The mice were randomly divided into 4 groups, with 5 mice per drug treated group, and 4 mice comprised the empty nanoparticle control group. Treatment was started on day 15 after engraftment of cells. The dose of pristimerin delivered in nanoparticles was 3mg/kg for each mouse and was administered by intravenous injection (IV) injection twice a week for a total of 4 weeks. The dose of cisplatin was 2.5mg/kg for each mouse and was administered by intraperitoneal (IP) injection twice a week for a total of 4 weeks. After 2 weeks of treatment, tumors were measured weekly using calipers, and volumes were calculated using the formula length x width2 /2.

MTDH silencing by CRISPR editing

MTDH expression knockout using CRISPR/Cas9 was achieved as described previously[14]. The sgRNA CAAAACAGTTCACGCCATGA targeted the coding region of the MTDH gene at 97686713 to 97686733 (Sequence ID: NC_000008.11 at Homo sapiens chromosome 8, GRCh38.p12). The sgRNA was cloned into lentiCRISPRv1 (Addgene Plasmid 49535, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). The viral vectors were produced in HEK293T cells following the manufacturer’s protocol. Endometrial cancer cells of Hec50 were infected with the lentivirus and cultured in the presence of puromycin. Single cell clones were selected by limiting dilution. MTDH deletion was confirmed by qPCR and by Western blotting.

Preparation of pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles

Pristimerin-loaded Poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles were prepared using the nanoprecipitation method as described previously[15]. Briefly, 2 mg of pristimerin and 20 mg of 75:25 Poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (Lactel Absorbable Polymers, Birmingham, AL) were dissolved in 3.4 ml of acetone, sonicated for 10 min (Branson® 5200), and then mixed with 0.6 ml of 97% ethanol. This organic solution was added drop wise into a stirred aqueous solution prepared by mixing 20 ml distilled water with 0.6 ml of 1% (w/v) D-α-Tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (Sigma Aldrich). The organic solvent in the nanoparticle suspension was evaporated under reduced pressure of 50 mBar for 6 h using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Laborota 4000-efficient). Nanoparticles were then washed 4 times using Amicon ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (MW cutoff = 100 kDa (EMD Millipore)) by centrifugation at 500 g for 20 min (Eppendorf® centrifuge 5804 R). Pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles were freshly prepared before each experiment.

Quantification of pristimerin loading

In order to determine pristimerin loading per mg of nanoparticles, freshly prepared pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles were frozen overnight and then lyophilized using a Labconco freeze dryer (FreeZone 4.5). Known amounts of lyophilized pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles were dissolved in acetonitrile, and then pristimerin loading was quantified using high performance liquid chromatography (HLPC, Waters, 2690 separations module) equipped with an ultraviolet detector (Waters, 2487 Dual λ absorbance detector) using 425 nm as the detection wavelength. The column was a Symmetry Shield™ RP 18, 5μm, 4.6 × 150 mm. Isocratic elution was carried out using a mobile phase consisting of a mixture of methanol and ultrapure water + 0.1 % (v/v) phosphoric acid (80:20) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with 10 µl as the injection volume. A standard curve of known concentrations of pristimerin solution in acetonitrile was generated and used to determine pristimerin loading in the nanoparticles.

Drug loading and encapsulation efficiency (%EE) were calculated from equations 1 and 2, respectively. In the equations, nanoparticles are abbreviated as “NPs.”

| (1) |

| (2) |

Pulldown of MTDH-associated RNAs by Flag tagged MTDH-fragments

MTDH fragments were established by cloning PCR products in pCMV6 vector (Origene, Rockville, MD) and transfected to Hec50 cells with MTDH short hairpin RNA knockdown[8]. Magna RIPTM (RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation) kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and real time PCR were used to pull down MTDH-associated RNAs and to identify mRNAs that associate with MTDH per the manufacturer’s protocol as previously described[8]. Antibody against MTDH (40–6500, 5µg/1ml, ThermoFisher, Inc., Waltham, MA) or FLAG antibody M2 (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used to pull down MTDH-associated mRNAs, and anti-IgG (5 µg/1ml, Millipore, Bedford, MA) was used as a negative control. FANCD2 and FANCI were detected by RT-qPCR. 18srRNA was used as control. Primer details are provided in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan Meier analysis was used to determine the association of MTDH amplification with survival in endometrial cancer TCGA dataset. Two-sided paired t-tests were used to compare test sets with controls. Two-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between control and treatment over a range of doses or times. P values are denoted as follows: “*” <0.05, “**”< 0.01, “***” <0.001, “****” <0.0001.

Results

MTDH depletion causes a reduction in FANCD2 and FANCI proteins

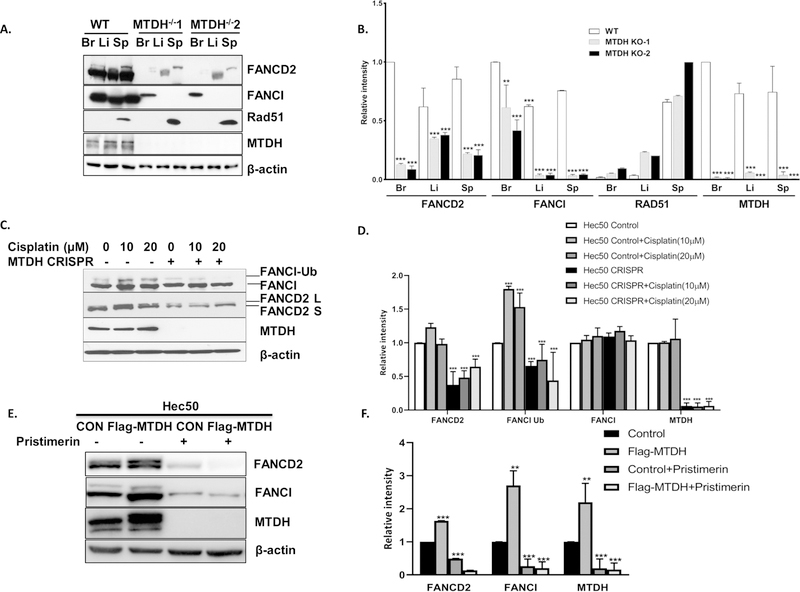

Our previous work established that MTDH binds mRNAs corresponding to FANCD2 and FANCI proteins[8]. This observation has been confirmed by analyzing FANCD2 and FANCI in GEO dataset GSE110260 by deep sequencing of MTDH-associated transcripts, which were precipitated by an anti-MTDH antibody after protein and mRNA crosslinking[9]. Of note, several regions within the FANCI and FANCD2 mRNA sequences pulled-down by MTDH antibody were found in GSE110260 (Table S2). To determine whether MTDH contributes to changes in FANCD2 and FANCI expression at the protein level, we examined expression of FANCD2, FANCI and other DNA repair proteins in tissues from MTDH knockout mice, which were generated by homozygous deletion of exon 3 in the Mtdh gene. A dramatic reduction of FANCD2 and FANCI was detected in the liver, brain and spleen from MTDH knockout mice, though expression of other DNA repair proteins such as Rad51 remained unchanged (Fig. 1A and 1B). Similarly, in endometrial cancer cells with genetic deletion of MTDH by CRISPR/Cas9 technology, we observed a marked reduction in FANCD2 protein expression as well as mono-ubiquitin conjugated FANCD2 in control and 10µM and 20µM cisplatin treated cells and a marked reduction of mono-ubiquitin conjugated FANCI in 10µM and 20µM cisplatin treated cells (Fig. 1C and 1D). Monoubiquitin-conjugated FANCD2 and FANCI may be used as a biomarker to determine if the FA pathway is competent or deficient and to predict sensitivity to DNA crosslinking therapeutic agents[16]. Reduction of monoubiquitin-conjugated FANCD2 and FANCI proteins indicates the reduction of activation of the FA repair pathway [17, 18]. In endometrial cancer cells with MTDH overexpression, a marked increase in FANCD2 and FANCI and mono-ubiquitin conjugated FANCD2 and FANCI was observed (Fig. 1E and 1F). By contrast, MTDH deletion and MTDH overexpression had no effect on mRNA levels on of FANCD2 and FANCI (Fig. S1), suggesting that the effect of MTDH on FA pathway protein expression is at the post-transcriptional level.

Fig. 1. FA family proteins FANCD2 and FANCI are significantly reduced in MTDH knockout mice and MTDH-depleted cancer cells and increased in MTDH overexpressed cancer cells.

(A) Expression of FANCD2 and FANCI protein was detected and quantified by Western blotting in the brain (Br), liver (Li) and spleen (Sp) from wild type mice and two MTDH homozygous knockout mice (MTDH KO1 and MTDH KO2). Rad51 and β-actin were also analyzed by Western blotting as controls for other DNA repair proteins and loading. (B) Quantification of Western blots in (A). With the exception of Rad51, all data are relative to wide type brain. For Rad51 data are relative to MTDH−/− 2 spleen. (C, D) FANCD2, FANCI and MTDH were detected and quantified by Western blotting in parental Hec50 cells and MTDH CRISPR knockout Hec50 cells in the absence or presence of DNA damage via cisplatin for 24 h. Labels denote ubiquitinated (Ub) FANCI and the long (L) and short (S) isoforms of FANCD2. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E,F) FANCD2, FANCI and MTDH were detected and quantified by Western blotting in empty vector transfected Hec50 cells and MTDH overexpressed Hec50 cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. Each figure is representative of three independent experiments.

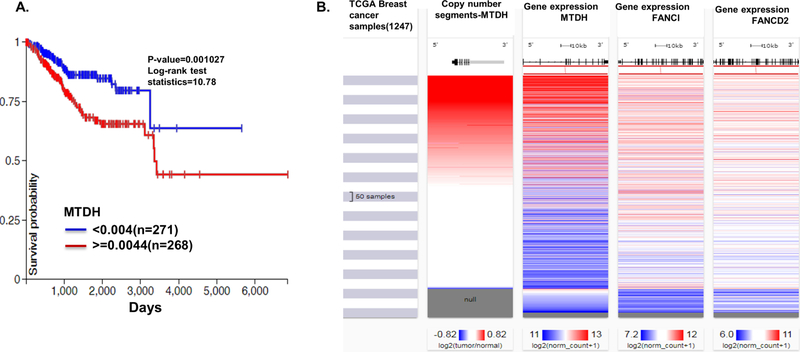

Analysis of the expression of MTDH and FANCI in endometrial and breast cancer patients

MTDH amplification negatively correlates with overall survival in breast cancer patients[5]. Using TCGA dataset for endometrial cancer, we substantiated that MTDH amplification is also associated with poor survival in endometrial cancer (Figure 2A). To analyze whether MTDH expression is correlated with FANCD2 and FANCI in TCGA dataset, we found that amplification and increased expression of MTDH also positively correlated with the expression of FANCI and FANCD2 in the TCGA dataset for breast cancer (Fig. 2B). A positive correlation of MTDH with FANCD2 and FANCI at mRNA level was also observed in endometrioid endometrial cancer patients (Table S2).

Fig. 2. Analysis of the expression of MTDH and FANCI in endometrial and breast cancer patients.

(A) MTDH amplification portends worse prognosis for endometrial cancer. Kaplan Meier analysis of MTDH copy number gain (after removal of germline copy number variants) as a measure of MTDH amplification in TCGA dataset for endometrial cancer. Blue: low MTDH copy number; red: high MTDH copy number, indicative of gene amplification. (B) MTDH amplification positively correlates with expression of FANCD2 and FANCI in breast cancer. Heat maps for MTDH copy number variations and gene expression of MTDH, FANCI, and FANCD2 in TCGA dataset for breast cancer.

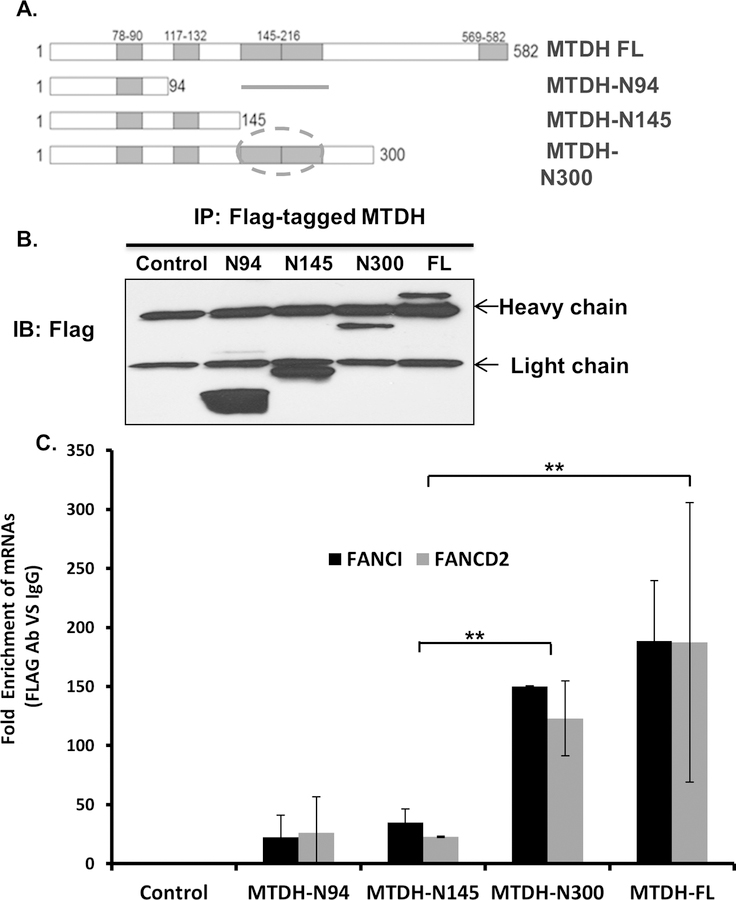

Identification of the region in MTDH that associates with FANCD2 and FANCI mRNAs

Our previous study showed four putative RNA binding regions in MTDH[8]. To identify the specific region in MTDH that binds mRNAs, FLAG-tagged fragments of MTDH were transiently expressed in Hec50 cells in which endogenous MTDH was knocked down (Fig. 3A, B). Protein extracts were subjected to anti-FLAG antibody pull-down followed by RT-qPCR to detect MTDH-bound FANCI and FANCD2 mRNAs. We found that residues 145–216 were essential for the association of MTDH with FANCD2 and FANCI mRNAs (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Identification of the region in MTDH that associates with FANCD2 and FANCI mRNAs.

(A) Schematic representation of full length MTDH and truncated MTDH constructs which contain different RNA binding domains. Circle denotes the region in MTDH that binds mRNAs (residues 145–260). (B) Immunoblot for flag-tagged MTDH fragments. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag, followed by Western blotting with anti-Flag antibody. (C) RNA immunoprecipatation of MTDH-associated mRNAs followed by RT-qPCR for FANCI and FANCD2. Data are presented as the fold enrichment of MTDH-bound FANCI and FANCD2 mRNA following immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag relative to IgG. Error bars represent the relative rate of enrichment of FANCD2 and FANCI from three independent experiments, P<0.01.

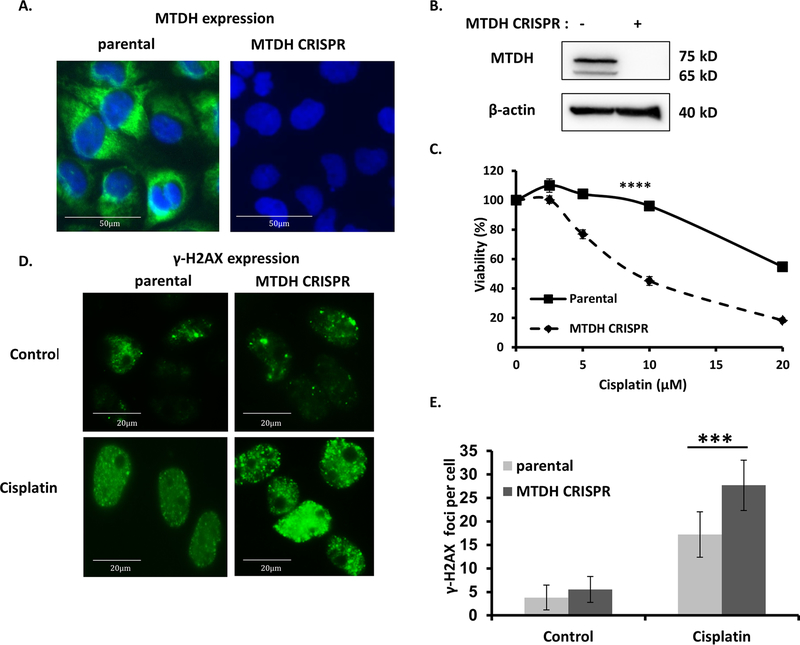

MTDH silencing increases γ-H2AX foci formation and sensitivity to cisplatin in cancer cells

The FA pathway plays a critical role in the repair of DNA cross-link damage induced by chemotherapeutic agents including cisplatin[19]. Consistent with previous reports[8], MTDH deficiency significantly increased sensitivity to the DNA damaging agent cisplatin (Fig. 4A–C). No difference of cell proliferation between cancer cells expressing scrambled sgRNA and cancer cells with multiple MTDH knockout clones by expressing MTDH sgRNA (Fig. S2). We next directly tested the impact of MTDH on DNA damage repair by assessing γ-H2AX foci formation, a standard biomarker to denote an increase in DNA damage[20]. Formation of cisplatin-induced γ-H2AX foci was significantly increased in MTDH-deficient Hec50 cells (Fig. 4D, E). From these data, we conclude that MTDH is required to repair cisplatin induced DNA damage.

Fig. 4. MTDH depletion increases sensitivity to cisplatin and accumulation of DNA damage in cancer cells.

(A) Fluorescent imaging of MTDH (green) and nuclei (blue, DAPI) in control and MTDH CRISPR knockout cancer cells. (B) Western blot confirming deletion of MTDH using CRISPR/Cas9 in Hec50 cells. β-tubulin is the loading control. (C) Sensitivity to cisplatin was examined in parental and MTDH CRISPR knockout Hec50 cells by the WST-1 assay from three independent experiments. ****P<0.0001 by two-way ANOVA. (D) Immunostaining was used to detect γ-H2AX foci in parental and MTDH CRISPR knockout Hec50 cells without treatment or treatment with 5 µM cisplatin for 16 h. (E) Quantification of γ-H2AX foci in cancer cells. Data are representative of 300 cells from three independent experiments, ***P<0.001.

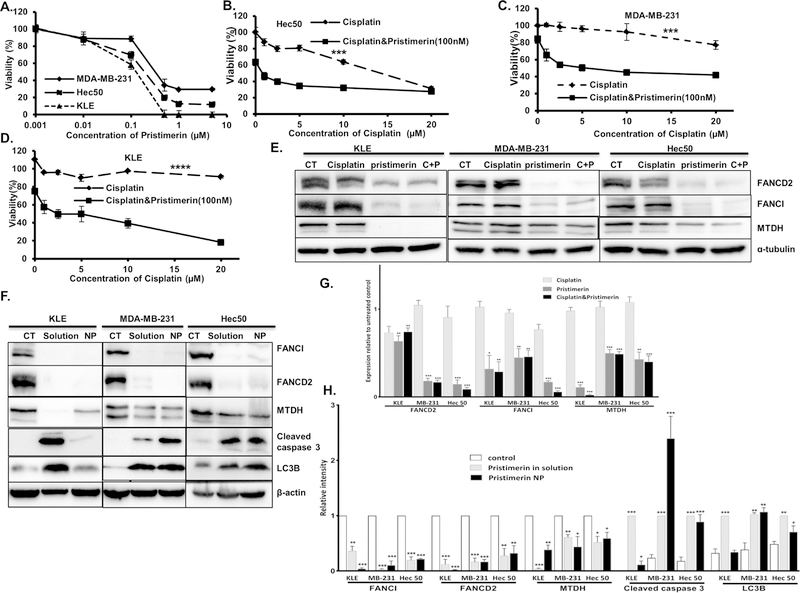

Pristimerin increases cisplatin sensitivity by downregulating MTDH

Directly targeting MTDH through genetic manipulation is not currently feasible in patients. Therefore, we next sought to identify novel small molecules that can decrease MTDH expression. A recent study in lung cancer cells found that celastrol, a natural agent, promotes proteasomal degradation of FANCD2, thereby increasing sensitivity to DNA crosslinking agents[21]. We found that celastrol can also reduce MTDH and FANCI protein levels in cancer cells (Fig. S3). However, celastrol is a leptin sensitizer and leads to weight loss in obese mice[22]. To avoid weight loss in cancer patients, we tested another compound with a similar quinonemethide triterpenoid structure, pristimerin, which has shown promising in tumor growth inhibition in preclinical study [23]. We first established that pristimerin decreases viability of Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cells, with IC50 values below 1 µM (Fig. 5A). Overexpression of MTDH was not protective of pristimerin-induced cell death (Fig. S4). No change of sensitivity to pristimerin was observed in scrambled sgRNA or multiple clones with MTDH depletion by sgRNA against MTDH (Fig.S5). At doses as low as 100 nM, pristimerin increased sensitivity to cisplatin in all three cancer cell lines (Fig. 5B–D). Importantly, pristimerin(in solution) decreased MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI protein levels when used as a single drug or in combination with cisplatin in all three tested cell lines (Fig. 5E). Overexpression of MTDH does not inhibit pristimerin induced decrease of MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI (Fig. 1E and 1F). These data demonstrate that treatment with pristimerin is a potential therapeutic approach to overcome the effects of high MTDH expression.

Fig. 5. Pristimerin increases cisplatin sensitivity in Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cancer cells.

(A) Viability of Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cells after treatment with pristimerin for 72 h was determined using WST-1 assay. (B-D) Viability of Hec50 (B), MDA-MB-231 (C) and KLE (D) cells after treatment with cisplatin alone or in combination with the indicated dose of pristimerin for 72 h was determined using WST-1 assay, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA. (E) Pristimerin decreased MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI protein levels when used as a single drug (1µM) or in combination with cisplatin (5µM) in Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cell lines. CT: untreated control; C+P: cisplatin + pristimerin. (F) Comparison of the effect of pristimerin in solution(1µM) and loaded into nanoparticles (NP) (40µM) on expression of MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI and induction of the apoptotic marker cleaved caspase 3 and the autophagy marker LC3 in Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cells. β-actin: loading control; CT: untreated. (G) Quantification of Western blots in (E). (H)Quantification of Western blots in (F) With the exception of cleaved caspase 3 and LC3B, all data are relative to control. For cleaved caspase 3 and LC3B data are relative to pristimerin in solution. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

Quantification and characterization of pristimerin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles

Similar to previous reported poor solubility and pharmacokinetics of celastrol[24], pristimerin in solution did not induce significant tumor growth inhibition in our preliminary study in PDX mouse model of endometrial cancer(data not shown). We therefore used a nanoparticle-based delivery approach to improve the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of pristimerin. Pristimerin was loaded into PLGA nanoparticles based on our previous studies[15]. The amount of pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles was quantified by HPLC. The drug loading and encapsulation efficiency of pristimerin were 168.70 ± 40.56 µg/mg and 101.22 ± 24.38%, respectively. Particles were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which demonstrated that the particle morphology is spherical with a smooth surface. The average particle size was 99.11 ± 18.30 nm (Fig. S6A). The zeta potential measured by the dynamic light scattering method was −46.82 ± 6.64 mV (Fig. S6B).

Nanoparticle-delivered pristimerin inhibits MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI in cancer cells

We first established that pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles reduced protein expression of MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI to levels similar to those achieved using pristimerin in solution in cell models (Fig. 5F). In addition, protein levels of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress biomarker CHOP, the apoptosis biomarker cleaved caspase 3 and the autophagy biomarker LC3B were all increased by treatment of Hec50, MDA-MB-231 and KLE cells with pristimerin in solution and pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles (Fig. 5F and Fig. S7). Pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles induce similar level of cleaved caspase 3, LC3B and CHOP expression compared to the pristimerin in solution in MDA-MB-231 and Hec50 cells, but less in KLE cells. These data substantiate the efficacy of nanoparticle-delivered pristimerin in downregulating MTDH as well as implicating the involvement of ER stress, apoptosis and autophagy in the mechanism of cell death in response to pristimerin.

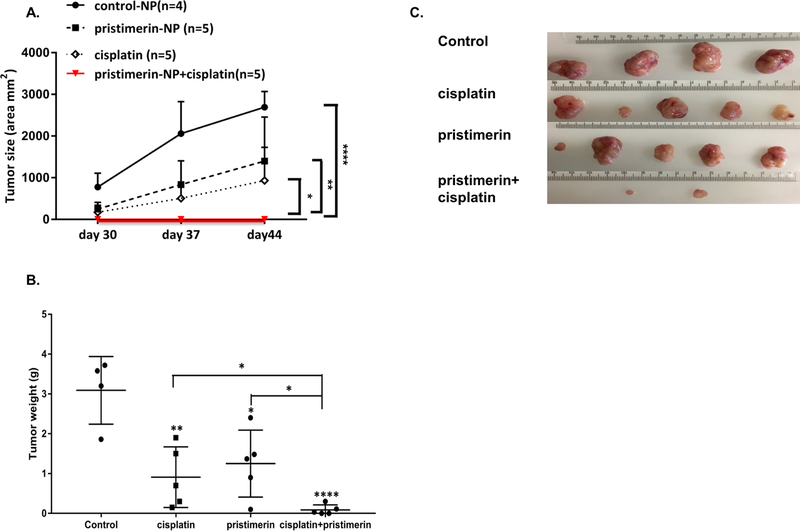

Cisplatin combined with pristimerin inhibits tumor growth in a patient-derived xenograft mouse model

To investigate the effects of pristimerin on tumor growth, we next performed studies in a PDX model of serous endometrial cancer. This model, denoted PDX1 herein, was previously developed by implanting a fresh surgically resected endometrial tumor specimen into the subcutis of immunocompromised mice[13]. PDX1 tumors are subsequently passaged in mice. We confirmed high expression of MTDH in this model, with levels similar to those observed in Hec50 cells (Fig. S8). Next, immunocompromised mice bearing PDX1 tumors were divided into four different treatment groups: control (empty) PLGA nanoparticles, cisplatin, nanoparticle-loaded pristimerin and the combination of cisplatin with pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles. Treatment with cisplatin or pristimerin alone significantly inhibited tumor growth as compared to control PLGA nanoparticles (p<0.05). However, the combination of cisplatin and nanoparticle-loaded pristimerin further decreased the tumor growth (p<0.001 compared to all other groups, Fig. 6A), with a corresponding reduction in tumor weight at 30 days after treatment (p<0.001) (Fig. 6B, C). Similar to Celastrol, pristimerin also caused weight loss in mice treated with nanoparticle-loaded pristimerin alone or in combination with cisplatin (Fig. S9). These data validate pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles as a potential treatment to restore sensitivity to cisplatin in tumors with MTDH upregulation.

Fig. 6. Nanoparticle-delivered pristimerin increases cisplatin sensitivity in a PDX model of endometrial cancer.

(A) Growth curves for tumor volumes in PDX1 mice. Treatment began on day 15 post-implantation of PDX1 and continued for 4 weeks. Pristimerin (NP): nanoparticle-loaded pristimerin, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA. (B) Tumor weight was determined at the completion of treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. control by Student’s t-test. (C) Images of tumor size at the completion of treatment. Note that pristimerin+cisplatin caused complete tumor regression in 3 of the 5 mice.

Discussion

Platinum compounds are some of the most effective broad-spectrum anti-cancer chemotherapeutic drugs[25]. They function by inducing DNA cross-linking damage in cancer cells in a wide range of cancer types. Unfortunately, drug resistance occurs gradually and frequently in patients whose tumors were initially sensitive to platinum agents[2]. One mechanism of resistance is an increased ability of cancer cells to repair platinum-induced DNA damage[26]. DNA interstrand-crosslink damage is mainly recognized by proteins in the FA pathway and subsequently repaired by the homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway[27]. The majority of studies of FA-mediated DNA repair in cancer focus on inactivating mutations in FA genes. Indeed, the 17 FA genes in the FA pathway are frequently mutated across 68 DNA sequence datasets of non-Fanconi Anemia human cancers, at a rate in the range of 15 to 35%[28]. BRCA2 is among these 17 genes, and studies in ovarian cancer demonstrate that tumors with mutations in BRCA2 are initially sensitive to platinum compounds due to loss of DNA repair capabilities[29].

Here we report that this canonical DNA repair mechanism can also be co-opted to drive chemoresistance. Specifically, we find that overexpression of MTDH up regulates FANCD2 and FANCI by interacting with and promoting translation of FANCD2 and FANCI mRNAs. By upregulating these DNA repair proteins, MTDH induces significant resistance to DNA-damaging agents by endowing cancer cells with an enhanced ability to repair damaged DNA. Consistent with our findings, others have found that FANCD2 expression is up regulated and correlates with poor outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma[30]. Despite a loss of protein expression, we did not detect any changes in mRNA levels of FANCD2 or FANCI in MTDH-deficient cells. Hence, we conclude that MTDH regulates FA family proteins at the post-transcriptional level. Consistent with this interpretation, MTDH has been found to bind to several target sequences in the coding region and 3-terminal untranslated region of FANCI (Table S3 herein and reference[9] ).

Since MTDH regulates the expression of a cadre of FA pathway factors through its novel RNA binding properties, we hypothesized that MTDH would be a good therapeutic target by which to increase sensitivity to platinum compounds. Currently, no MTDH specific inhibitors are available due to the lack of canonical catalytic domains in MTDH. The discovery that pristimerin can efficiently reduce expression of MTDH and FA pathway proteins provides a potential solution to repurpose this anti-inflammatory drug as a novel agent to combine with chemotherapy. Pristimerin is a natural triterpenoid isolated from the Celastraceae and Hippocrateaceae plant families and is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine as an anti-inflammatory medication[31]. Multiple preclinical studies in a wide range of cancer types, including breast cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer and pancreatic cancer, confirm the anti-tumor activity of pristimerin[23]. Mechanistic studies have suggested that the anti-inflammatory activity of pristimerin is accomplished through inhibition of the well-known pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB via inhibition of the NF-κB inhibitor IKK[32]. In addition, pristimerin has been shown to inhibit chymotrypsin-like protease activity [33], suggesting that pristimerin is a dual proteasome and NF-κB inhibitor. Of note, NF-κB regulates expression of MTDH by binding to the promoter of the MTDH gene[34]. Therefore, we speculate that pristimerin accomplishes the reduction of MTDH expression by interfering with NF-κB-mediated transcription of this gene.

To enhance drug solubility, stability and accumulation in the tumor, a nanoparticle formulation was used to deliver pristimerin to tumors in vivo[15]. Nanoparticles have been extensively utilized for delivering therapeutic and diagnostic agents. Nanoparticles offer a superior dissolution profile of their payload due to their unique size range that governs a vast increase in the exposed surface area to the dissolution medium[35]. Nanoparticles prepared from natural or synthetic polymers modify drug release and create a sustained or controlled release profile[36]. The specific nanoparticle formulation used to deliver pristimerin, which consists of PLGA at a monomer ratio of 75:25 and TPGS surfactant, improves therapeutic efficacy of pristimerin through enhanced drug uptake and accumulation. TPGS has a unique ability to inhibit P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux transporter, a transporter that is highly overexpressed in many cancers[37, 38], which can extrude drug substances out of the cells, reducing their intracellular concentration and effect. Many studies indicated that pristimerin is a substrate to P-gp, therefore loading pristimerin in NPs containing TPGS would enhance its intracellular accumulation through inhibiting its efflux[39]. Our lab has recently demonstrated that loading a substrate to P-gp efflux transporter in NPs prepared with TPGS significantly improved the substrates intracellular accumulation once compared to its soluble form[40]. Regarding cancer treatment, nanoparticles less than 200 nm in diameter offer superior accumulation at the tumor site due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.

In conclusion, our data support the role of MTDH overexpression as a mechanism that leads to resistance to chemotherapy via its novel RNA binding function. We also demonstrate that inhibition of MTDH expression leads to a significant reduction in FA DNA repair proteins, and this effect can be phenocopied by treating with pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles. Thus, our data provide a unique foundation for the future interrogation of these novel nanoparticles as a therapeutic strategy to improve chemosensitivity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Endometrial cancer patients with high copy number of MTDH show poor outcome

Inhibition MTDH increases DNA damage induced γ-H2Ax foci formation and sensitivity to Cisplatin

MTDH binds with mRNAs encoding for FANCD2 and FANCI

Pristimerin-loaded nanoparticles inhibits MTDH, FANCD2 and FANCI to increase sensitivity to cisplatin

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIH grant numbers R01CA184101 (XM and KKL), R37CA238274 (SY) and R01CA99908 (KKL). XM was supported by an Oberley award from The Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center (HCCC) and Developmental Research Program (DRP) grant of Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) NIH grant number P50CA174521. AKS was supported by the Lyle and Sharon Bighley Chair of Pharmaceutical Sciences. KE was supported by the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education for a graduate fellowship award. HCCC at the University of Iowa is supported by National Cancer Institute Award P30CA086862.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

KWT and DD are co-founders of Immortagen, Inc. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors. All other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Brabec V, Kasparkova J. Modifications of DNA by platinum complexes. Relation to resistance of tumors to platinum antitumor drugs. Drug resistance updates 2005;8:131–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Muggia FM. Recent updates in the clinical use of platinum compounds for the treatment of gynecologic cancers. Seminars in oncology 2004;31:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meng X, Thiel KW, Leslie KK. Drug resistance mediated by AEG-1/MTDH/LYRIC. Advances in cancer research 2013;120:135–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Song Z, Wang Y, Li C, Zhang D, Wang X. Molecular Modification of Metadherin/MTDH Impacts the Sensitivity of Breast Cancer to Doxorubicin. PloS one 2015;10:e0127599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hu G, Chong RA, Yang Q, Wei Y, Blanco MA, Li F, et al. MTDH activation by 8q22 genomic gain promotes chemoresistance and metastasis of poor-prognosis breast cancer. Cancer cell 2009;15:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moelans CB, van der Groep P, Hoefnagel LDC, van de Vijver MJ, Wesseling P, Wesseling J, et al. Genomic evolution from primary breast carcinoma to distant metastasis: Few copy number changes of breast cancer related genes. Cancer letters 2014;344:138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Emdad L, Das SK, Hu B, Kegelman T, Kang DC, Lee SG, et al. AEG-1/MTDH/LYRIC: A Promiscuous Protein Partner Critical in Cancer, Obesity, and CNS Diseases. Advances in cancer research 2016;131:97–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meng X, Zhu D, Yang S, Wang X, Xiong Z, Zhang Y, et al. Cytoplasmic Metadherin (MTDH) provides survival advantage under conditions of stress by acting as RNA-binding protein. The Journal of biological chemistry 2012;287:4485–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hsu JC, Reid DW, Hoffman AM, Sarkar D, Nicchitta CV. Oncoprotein AEG-1 is an endoplasmic reticulum RNA-binding protein whose interactome is enriched in organelle resident protein-encoding mRNAs. RNA 2018;24:688–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nakanishi K, Yang YG, Pierce AJ, Taniguchi T, Digweed M, D’Andrea AD, et al. Human Fanconi anemia monoubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005;102:1110–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Goldman M, Craft B, Kamath A, Brooks A, Zhu J, Haussler D. The UCSC Xena Platform for cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. bioRxiv 2018.

- [12].Meng X, Yang S, Zhang Y, Wang X, Goodfellow RX, Jia Y, et al. Genetic Deficiency of Mtdh Gene in Mice Causes Male Infertility via Impaired Spermatogenesis and Alterations in the Expression of Small Non-coding RNAs. The Journal of biological chemistry 2015;290:11853–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Luo W, Wu F, Elmaoued R, Beck BB, Fischer E, Meng X, et al. Amifostine enhancement of the anti-cancer effects of paclitaxel in endometrial cancer is TP53-dependent. International journal of oncology 2010;37:1187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kavlashvili T, Jia Y, Dai D, Meng X, Thiel KW, Leslie KK, et al. Inverse Relationship between Progesterone Receptor and Myc in Endometrial Cancer. PloS one 2016;11:e0148912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ebeid K, Meng X, Thiel KW, Do AV, Geary SM, Morris AS, et al. Synthetically lethal nanoparticles for treatment of endometrial cancer. Nature nanotechnology 2018;13:72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ulrich HD, Walden H. Ubiquitin signalling in DNA replication and repair. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2010;11:479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sims AE, Spiteri E, Sims RJ 3rd, Arita AG, Lach FP, Landers T, et al. FANCI is a second monoubiquitinated member of the Fanconi anemia pathway. Nature structural & molecular biology 2007;14:564–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nepal M, Che R, Ma C, Zhang J, Fei P. FANCD2 and DNA Damage. International journal of molecular sciences 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kim H, D’Andrea AD. Regulation of DNA cross-link repair by the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Genes & development 2012;26:1393–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nowsheen S, Wukovich RL, Aziz K, Kalogerinis PT, Richardson CC, Panayiotidis MI, et al. Accumulation of oxidatively induced clustered DNA lesions in human tumor tissues. Mutation research 2009;674:131–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang GZ, Liu YQ, Cheng X, Zhou GB. Celastrol induces proteasomal degradation of FANCD2 to sensitize lung cancer cells to DNA crosslinking agents. Cancer science 2015;106:902–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu J, Lee J, Salazar Hernandez MA, Mazitschek R, Ozcan U. Treatment of obesity with celastrol. Cell 2015;161:999–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yousef BA, Hassan HM, Zhang LY, Jiang ZZ. Anticancer Potential and Molecular Targets of Pristimerin: A Mini-Review. Current cancer drug targets 2017;17:100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Guo L, Luo S, Du Z, Zhou M, Li P, Fu Y, et al. Targeted delivery of celastrol to mesangial cells is effective against mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nature communications 2017;8:878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Desoize B, Madoulet C. Particular aspects of platinum compounds used at present in cancer treatment. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2002;42:317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tortorella L, Langstraat CL, Weaver AL, McGree ME, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Dowdy SC, et al. Uterine serous carcinoma: Reassessing effectiveness of platinum-based adjuvant therapy. Gynecologic oncology 2018;149:291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ceccaldi R, Sarangi P, D’Andrea AD. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2016;17:337–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shen Y, Lee YH, Panneerselvam J, Zhang J, Loo LW, Fei P. Mutated Fanconi anemia pathway in non-Fanconi anemia cancers. Oncotarget 2015;6:20396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sakai W, Swisher EM, Jacquemont C, Chandramohan KV, Couch FJ, Langdon SP, et al. Functional restoration of BRCA2 protein by secondary BRCA2 mutations in BRCA2-mutated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer research 2009;69:6381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Komatsu H, Masuda T, Iguchi T, Nambara S, Sato K, Hu Q, et al. Clinical Significance of FANCD2 Gene Expression and its Association with Tumor Progression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anticancer research 2017;37:1083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tong L, Nanjundaiah SM, Venkatesha SH, Astry B, Yu H, Moudgil KD. Pristimerin, a naturally occurring triterpenoid, protects against autoimmune arthritis by modulating the cellular and soluble immune mediators of inflammation and tissue damage. Clinical immunology 2014;155:220–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hui B, Yao X, Zhou Q, Wu Z, Sheng P, Zhang L. Pristimerin, a natural anti-tumor triterpenoid, inhibits LPS-induced TNF-alpha and IL-8 production through down-regulation of ROS-related classical NF-kappaB pathway in THP-1 cells. International immunopharmacology 2014;21:501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tiedemann RE, Schmidt J, Keats JJ, Shi CX, Zhu YX, Palmer SE, et al. Identification of a potent natural triterpenoid inhibitor of proteosome chymotrypsin-like activity and NF-kappaB with antimyeloma activity in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2009;113:4027–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sarkar D, Park ES, Emdad L, Lee SG, Su ZZ, Fisher PB. Molecular basis of nuclear factor-kappaB activation by astrocyte elevated gene-1. Cancer research 2008;68:1478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kelidari HR, Saeedi M, Akbari J, Morteza-semnani K, Valizadeh H, Maniruzzaman M, et al. Development and Optimisation of Spironolactone Nanoparticles for Enhanced Dissolution Rates and Stability. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017;18:1469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Breitenbach A, Li YX, Kissel T. Branched biodegradable polyesters for parenteral drug delivery systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2000;64:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Duhem N, Danhier F, Préat V. Vitamin E-based nanomedicines for anti-cancer drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2014;182:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Collnot E-M, Baldes C, Wempe MF, Kappl R, Hüttermann J, Hyatt JA, et al. Mechanism of Inhibition of P-Glycoprotein Mediated Efflux by Vitamin E TPGS: Influence on ATPase Activity and Membrane Fluidity. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2007;4:465–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhao X, Wu Y, Wang D. Effects of Glycyrrhizic Acid on the Pharmacokinetics of Pristimerin in Rats and its Potential Mechanism. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics 2018;43:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ebeid K, Meng X, Thiel KW, Do A-V, Geary SM, Morris AS, et al. Synthetically lethal nanoparticles for treatment of endometrial cancer. Nature Nanotechnology 2018;13:72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.