Abstract

Background

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease that causes chronic, watery diarrhoea. Microscopic colitis is usually effectively treated with budesonide, but some patients are refractory. Data on alternative treatments are sparse.

Aims

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively evaluate outcome of microscopic colitis patients receiving anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy at our centre.

Methods

Treatment results, including side effects, for all microscopic colitis patients receiving anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy were registered at week 12 and at end of follow-up. Clinical remission was defined as a mean of <3 stools and <1 watery stools/day/week and clinical response as a 50% reduction of mean stool frequency/day/week. Induction and maintenance treatment was either adalimumab or infliximab.

Results

The study cohort comprised 18 patients; mean age at diagnosis was 47 years (range 19–77). Ten and eight patients, respectively, received adalimumab and infliximab as first-line anti-tumour necrosis factor; seven patients received second-line anti-tumour necrosis factor due to non-response, loss of response or side effects. At week 12, 9/18 patients had achieved remission, 6/18 were responders and 3/18 were non-responders. Of the nine remission patients, 3/18 (16%) had long-lasting clinical remission post-induction therapy alone. Five patients (28%) (one first-line, four second-line anti-tumour necrosis factor) were in remission and one patient (6%) responded to maintenance treatment; follow-up was mean 22 (range 4–60) months. Six patients (33%) had minor, reversible side effects.

Conclusions

Over half of budesonide-refractory microscopic colitis patients can achieve clinical remission or response on anti-tumour necrosis factor agents. Prospective studies are mandatory to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatments in budesonide-refractory microscopic colitis.

Keywords: Microscopic colitis, biological treatment, budesonide refractory, collagenous colitis, lymphocytic colitis

Introduction

Microscopic colitis (MC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that consists of two subgroups: collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). MC is characterized by chronic, watery non-bloody diarrhoea and macroscopically normal or nearly normal colonoscopy. It is diagnosed by typical histopathological findings and is mostly observed in middle-aged female patients. It has been recognized as a common IBD with incidence rates rising to approximately 25/100,000 inhabitants in certain geographic areas.1,2 Although MC is not linked to increased mortality rate, patients’ quality of life (QoL) is significantly decreased even when in remission.3

The pathogenesis of MC has been associated with drugs (e.g. PPI, NSAIDs, SSRI),4 environmental factors5 (e.g. smoking) and microbial dysbiosis.6 Furthermore, faecal stream diversion studies have led to the hypothesis that an unknown luminal agent is involved in the inflammation.7 The few immunological studies available in MC have shown an increased Th18 and a mixed Th1/Th17 cytokine expression.9 On a cellular level increased percentages of proliferating, memory, cytotoxic and helper T cells are present.10 Even though increased levels of mucosal tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and TNF-α gene polymorphisms are associated with increased susceptibility for MC; the mechanism of action of TNF-a in MC is unknown.11

Empirical data have shown that some patients with MC can be successfully treated with antidiarrhoeal treatment (loperamide, cholestyramine). However, budesonide is the only treatment tested in numerous randomised controlled studies and it has proven to be highly effective in inducing remission in both CC12–14 and LC15,16 with remission rates of roughly 80%. However, approximately 60%13,17 of these responders experience a relapse after budesonide cessation which indicates that the disease course is not changed.

When budesonide treatment fails, immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate and thiopurines have been tested. The use of methotrexate has produced conflicting data with one study reporting treatment response in 16/19 patients18 and in another study remission in 7/12 patients,19 while in a third study none of the nine patients achieved remission.20 It can be speculated that the different results are attributed to different patient cohorts (e.g. budesonide refractory vs dependant patients), the prospective or retrospective design of the studies, the form of administration and, finally, the criteria for defining remission or response. However, in general, methotrexate has not become a mainstream treatment. Case series from three European centres, as well as one American centre, have shown that thiopurine treatment (duration for a median of four months) in MC can lead to remission in approximately 40% of cases (76% with simultaneous budesonide which was tapered in two months),19 but a high percentage of patients experience side effects eventually leading to discontinuation of treatment.19,21

Finally, many patients can be refractory to budesonide and to the aforementioned therapies. In one cohort study from Spain, the fraction of individuals that were considered refractory to diverse medical therapy (cholestyramine, mesalazine, prednisone, budesonide, antibiotics and azathioprine) was 1.3%22 of the total MC patient population. It is well established that biological treatments have become the standard treatment for moderate to severe IBD. In MC, fewer data are available but small case series (3–4 patients),22–24 the largest study including 10 patients,19 with budesonide-refractory MC patients treated with anti-tumour necrosis factors (anti-TNFs) have shown favourable outcomes. We are presenting our single-centre retrospective case series of MC patients’ refractory to budesonide who have received anti-TNF treatment.

Methods

This is a retrospective study looking at all well-known patients that were attached to the out-patient clinic in Linköping University Hospital. Patients that still had active disease despite maintenance treatment with 6–9 mg budesonide for at least eight weeks were defined as being budesonide-refractory. The Hjortswang criteria were used to define disease activity, accordingly, patients experiencing more than a mean of ≥3 stools or a mean of ≥1 watery stool per day/week were considered to have active MC while those experiencing a mean <3 and a mean <1 watery stools per day/week were considered to be in remission.25 Response was defined as ≥50% decrease in stool frequency and <50% improvement was defined as non-response. The histological criteria for LC were an inflammation of the lamina propria and >20 lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells, and for CC a thickened subepithelial collagen band >10 µm had to be present. Clinical data, demographics, histology, laboratory results and the type of anti-TNF agent were collected retrospectively through the electronic medical data system. The induction treatment for adalimumab (ADA) was 160/80/40 mg at weeks 0, 2, 4; the maintenance dose was initially 40 mg every other week but could be adjusted to either 80 mg every other week or 40 mg weekly. The induction treatment for infliximab (IFX) was 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and maintenance 5 mg/kg every eight weeks. All patients were followed until 1 October 2018.

The study was approved by the ethical review board in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2012/216-31; dated 24 August 2012) and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

Statistical analyses

Data are mainly descriptive. Continuous data are expressed as mean and range. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies.

Results

Our patient group consisted of 18 patients, 16 with CC (88%) and two with LC (12%). Their demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. All patients had budesonide-refractory MC with an active disease according to the Hjortswang criteria at the time of anti-TNF treatment. All included patients had negative transglutaminase antibodies except one patient who was diagnosed with coeliac disease many years before the MC diagnosis and had normal histology (duodenum) and negative transglutaminase antibodies on a gluten free diet. All drugs that have the potential to induce or trigger MC were paused prior to anti-TNF therapy without any symptom relief.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF)-treated patients with microscopic colitis (MC).

| MC (n = 18) | |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 14 (78) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (range) | 47 (19–77) |

| Age at start of first anti-TNF, mean (range) | 50 (20–80) |

| Disease duration (months), mean (range) | 48 (4–96) |

| Follow-up of adalimumab first line (months), mean (range) | 69 (34–95) |

| Follow-up of adalimumab second line (months), mean (range) | 10 (6–15) |

| Follow-up of infliximab first line (months), mean (range) | 14 (6–20) |

| Follow-up of infliximab second line (months), mean (range) | 52 (36–68) |

| Number of stools/day active disease, mean (range) | 10 (4–20) |

| Number of watery stools/day active, mean (range) | 8 (3–15) |

| Previous medication, n (%) | |

| Budesonide | 18 (100) |

| Bile acid binders | 13 (72) |

| Loperamide | 13 (72) |

| Methotrexate | 4 (22) |

| Thiopurines | 5 (28) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 11 (61) |

| Former smoker | 4 (22) |

| Non smoker | 3 (17) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| COPD | 2 (11) |

| Psoriasis | 2 (11) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | 1 (6) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 1 (6) |

| Raynaud's disease | 1 (6) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 3 (17) |

| TIA or stroke | 2 (11) |

| Hypertension | 2 (11) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 2 (11) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (6) |

| Mild kidney failure (GFR > 60 ml/min) | 1 (6) |

| Cervix dysplasia treated with diathermia | 2 (11) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma in situ | 1 (6) |

| Concomitant medication at 12 weeks and follow-up, n (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 0 (0) |

| Immunomodulatorsa | 0 (0) |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Including azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate.

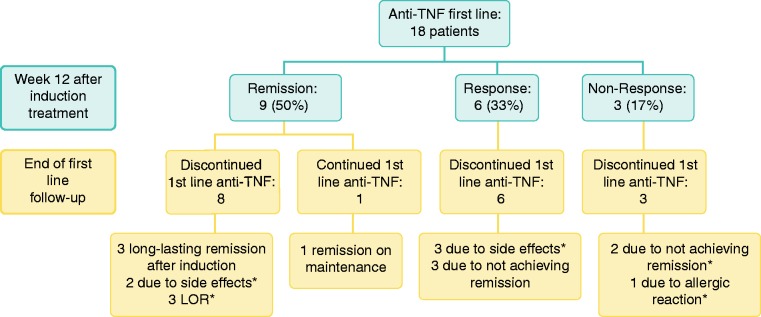

First-line anti-TNF agents

In total 18 patients received first-line anti-TNF agents as first biological treatment. At week 12, nine patients had achieved clinical remission (50%), six a clinical response (33%) and three were non-responders (17%). The results of induction treatment at week 12 and the last follow-up of first-line anti-TNF are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

First-line anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in microscopic colitis (MC). Results after induction treatment of eight patients with infliximab (IFX) (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6) at week 12 and 10 patients with adalimumab (ADA) at week 12 after 160/80/40 mg treatment at weeks 0, 2, 4 as well as at end of follow-up. End of follow-up for adalimumab (ADA); mean 69 (range 34–95) months. End of follow-up for IFX; mean 14 (range 6–20) months. * Patients switched to second-line anti-TNF. LOR: loss of response.

Subcategories

IFX as first anti-TNF

Eight of the 18 patients described above received IFX as first treatment. At week 12, five patients had achieved clinical remission (63%), two had a clinical response (25%) and one was a non-responder (12%). It must be noted that the non-responder received only one IFX dosage due to an allergic reaction with urticaria, and one of the responders discontinued IFX after two induction dosages due to the side effects of joint pain and fever. The other responder discontinued IFX after induction because of lack of remission and did not wish to continue with IFX or try ADA. Of the five patients that achieved remission at week 12, one was in remission after induction treatment only (end of follow-up: week 17), one patient was in remission on IFX maintenance every eight weeks (end of follow-up: week 25), two patients had loss of response (LOR) due to anti-drug-antibodies at week 17 and week 80, respectively, and one patient developed side effects (paraesthesia and pruritus) and IFX was discontinued at week 36. All side effects were mild and resolved after treatment was stopped. Budesonide was tapered off within three weeks from IFX induction treatment for all patients. End of first-line follow-up for IFX was mean 14 (range 6–20) months.

ADA as first-line anti-TNF

Ten of the 18 patients described above started with ADA as their first biological treatment. At week 12, four patients had achieved remission (40%), four were responders (40%) and two were non-responders (20%). Out of the four patients that achieved remission, two stopped treatment after induction and remained in remission until last follow-up at 65 and 91 months, respectively. One patient maintained on 80 mg every other week remained in remission for 60 months, but thereafter experienced LOR and is now being considered for loop-ileostomy due to intractable symptoms (no trough levels or anti-drug antibodies were measured). The last patient achieving remission on induction treatment had a relapse after three months and presented with intermittent rise in liver enzymes of unknown origin (all laboratory tests were negative) so ADA was not reintroduced. This patient recovered without any remaining rise in liver function. Of the four patients that were responders at week 12, two patients had to stop treatment after only two further dosages of ADA because of side effects (vomiting and nausea). All side effects resolved after treatment was discontinued. The remaining two patients that were responders did not achieve remission on maintenance and were discontinued from ADA treatment at week 52. The two non-responders received all three ADA induction doses. All patients were tapered off budesonide within two weeks after the start of ADA induction treatment. End of first-line ADA follow-up; mean 69 (range 34–95) months.

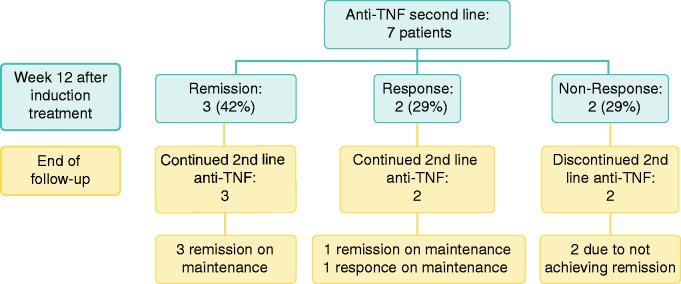

Switch within class to second anti-TNF treatment

Seven patients were switched to second-line anti-TNF agents; two from ADA to IFX and five from IFX to ADA. At week 12, three patients had achieved clinical remission (42%), two had a clinical response (29%) and two were non-responders (29%). The results of induction treatment at week 12 and the last follow-up are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Second-line (switch) anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) treatment in microscopic colitis (MC). Results after induction treatment -two patients infliximab (IFX) (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6) at week 12 and five patients ADA at week 12 after 160/80/40 mg treatment at weeks 0, 2, 4 as well as at end of follow-up. End of follow-up for ADA; mean 10 months (range 6–15 months). End of follow-up for IFX was mean 52 (range 36–68) months.

Subcategories

IFX second line

As mentioned above, from the 10 patients that initially received ADA, two patients (one non-responder and one patient in remission who developed side effects) were subsequently switched to IFX. Neither of these two patients were responders or achieved remission. Both had intractable symptoms leading to a very poor QoL, which resulted in a loop-ileostomy in each case. End of follow-up was mean 52 (range 36–68) months.

ADA second line

Of the eight patients that initially received IFX, five patients (one non-responder, one responder and three who were initially in remission, but two patients had LOR and one patient had an allergic reaction) were switched to ADA. Of these five patients who switched from IFX to ADA induction treatment, three (60%) had achieved remission and two (40%) were responders at week 12. At the end of follow-up (mean 10 (range 6–15) months), four patients were in remission on ADA maintenance (three on 40 mg every week and one on 40 mg every other week) and one was a responder on maintenance treatment (40 mg every week).

Discussion

Despite budesonide being very effective in a large percentage of MC patients there are sparse data available regarding appropriate therapies for refractory individuals. To our knowledge, this is the largest published case series of budesonide-refractory patients receiving anti-TNF treatment. Our results show that half of these patients can achieve remission and one-third are responders with first-line anti-TNF treatment at week 12. Three patients (16%) had a long-lasting clinical remission (years) after induction therapy alone and one patient had long-term remission on first-line anti-TNF. During the study, seven patients were switched to a second anti-TNF induction treatment due to LOR, side effects or non-response; and three (42%) achieved remission, two (29%) were responders and two (29%) were non-responders. At the end of follow-up (mean 22 (range 6–68) months) of both anti-TNF regimes, five patients (28%) were in remission and one patient (5%) was a responder on maintenance treatment. These data indicate that anti-TNF treatment can be a reasonable option in budesonide-refractory patients.

To date, experience with anti-TNF treatment in MC is limited; with a risk for selection bias as cases with a positive outcome are more likely to be reported. In the most recent study by Cotter et al., 10 MC patients were treated with anti-TNF demonstrating that 40% of patients achieved clinical remission and 40% gave a response.19 These results are strikingly similar to ours, possibly because the same disease activity criteria were used. However, direct comparison is hampered as the authors did not specify budesonide refractoriness or MC subgroup type, used mostly IFX (8/10 patients) and the follow-up period was much shorter, with a median of four months compared to 22 months in our cohort.19

Our longer follow-up also made it possible to study LOR over time and whether there was a need for second-line anti-TNF. Three patients experienced LOR after a mean 28 months on the first-line anti-TNF maintenance treatment and were switched. Unfortunately, antibody and drug trough levels were not obtained regularly (only in two patients) so no conclusions can be drawn for the LOR. In total, seven patients switched anti-TNF agent and five patients experienced remission or response. So far, no patient on second-line anti-TNF maintenance treatment (mainly ADA) with a mean follow-up time of 10 months has had LOR or side effects. However, in our study it became apparent, when embarking on anti-TNF maintenance treatment, that many patients need a higher dose or shorter interval to maintain remission; adjustments that were purely based on clinical judgement.

An interesting finding in our study is the fact that three patients (16%) remained in long-lasting remission after receiving induction therapy alone. In IBD, successful induction treatment with anti-TNF is usually followed by maintenance treatment, since stopping anti-TNF in refractory patients without any other ongoing maintenance therapy is associated with high risk of relapse.26 However, in MC our results indicate that it could be reasonable to stop after induction therapy with close patient follow-up and wait and see.

It is also noteworthy that the mean age of our patients is 47 years, which is clearly younger than the average MC population. In a previous study it was demonstrated that age <60 years is a risk factor for clinical relapse.17 Furthermore, our cohort had a very high rate of current and previous smokers which is known to be a risk factor for MC. As a mean, smokers receive a diagnosis of MC 10 years earlier, have more watery diarrhoea and are less likely to respond to budesonide treatment than non-smokers.27,28 However, we did not see any correlation between smoking status and response to anti-TNF treatment.

Physicians are still hesitant to prescribe anti-TNF agents to MC patients because older age is considered a risk factor for anti-TNF therapy and can increase the risk of developing serious side effects. Moreover, it is more likely that elderly patients have other comorbidities, which could turn out to be a hindrance for such therapy. However, none of our patients, as indicated in Table 1, had other diseases such as cancer, heart or kidney failure which could have increased the risk for severe side effects under anti-TNF therapy. Since anti-TNF has no labelled indication for MC, and MC is a benign disease, doctors could be more prone to discontinue the drug as soon side effects arise. In our cohort, side effects occurred in six out of 18 patients (33%), but fortunately no serious consequences occurred and all symptoms resolved after treatment was discontinued. These results are in concordance with other smaller cohorts of MC patients given anti-TNF.22,24

The strength of this case series is the comparably large size of a relatively homogeneous group of MC patients, all of whom were budesonide-refractory. The strict use of the Hjortswang criteria allowed better characterisation of activity and remission, and provided the basis for a clearer interpretation of the results. All patients were treated at the same centre by the same gastroenterologist who documented all clinical findings and side effects. Since it is less probable that randomised controlled studies of biological drugs in MC will be performed in the future due to the difficulty of enrolling sufficient patients, the value of such case series is important in clinical decision-making.

On the other hand, the retrospective nature of our study with its inherent limitations such as potential selection bias and inability to control cofounding factors is a clear weakness of the study. Also we could not retrieve missing data and there was lack of specific documentation (e.g. QoL was not carried out systematically). LC patients were not equally represented making it questionable whether our results can be generalised. However, LC and CC can normally not be distinguished from a clinical and therapeutic point of view. We also have not followed up our patients with biopsies during treatment so we have no data about the effect anti-TNF might have on the thickness of the subepithelial collagen layer or the inflammation in the lamina propria. Finally, as patients were included consecutively, the duration of follow-up was inevitably shorter in some cases.

In conclusion, anti-TNF treatment seems to be effective and safe in more than half of patients and can be considered in budesonide-refractory MC patients. As these patients have a very poor QoL, and we believe it is justifiable to initiate biological treatment with the aim of improving QoL and avoiding surgery. When initiating anti-TNF therapy in MC patients, the same routines and precautions should be followed as in classic IBD. There should be a special focus on comorbidity and contraindications, especially in the elderly, which could increase the risk for severe side effects and decisions, should be made on an individual basis. If available, drug monitoring should be applied as LOR can occur and switching to a second anti-TNF agent might be necessary. In our experience, MC patients on anti-TNF maintenance quite frequently require higher doses or the time intervals have to be shortened in order for patients to remain in clinical remission. Prospective randomised studies are mandatory but difficult to realise due to limited numbers of patients. Also combining anti-TNF with immunomodulators to avoid anti-drug antibody production should be tested in the future.

Acknowledgements

All authors were involved and active in the study concept and design as well as writing and drafting of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

AM has received research grant from Ferring, consultancies from Tillotts, Ferring, Dr Falk Pharma and Vifor. All other authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was issued by the regional Ethics committee, Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2012/216-31).

Funding

This study was funded by an Grant, Region Östergötland, Sweden and a Grant, Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden.

Informed consent

All patients have given informed consent to enter the trial.

References

- 1.Münch A, Aust D, Bohr J, et al. Microscopic colitis: Current status, present and future challenges Statements of the European Microscopic Colitis Group. J Crohn’s Colitis 2018; 6: 932–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonderup OK, Hansen JB, Teglbjaerg PS, et al. Long-term budesonide treatment of collagenous colitis: A randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Gut 2009; 58: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyhlin N, Wickbom A, Montgomery SM, et al. Long-term prognosis of clinical symptoms and health-related quality of life in microscopic colitis: A case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonderup OK, Fenger-Grøn M, Wigh T, et al. Drug exposure and risk of microscopic colitis: A nationwide Danish case-control study with 5751 cases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 1702–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth B, Gustafsson RJ, Jeppsson B, et al. Smoking- and alcohol habits in relation to the clinical picture of women with microscopic colitis compared to controls. BMC Womens Health 2014; 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer H, Holst E, Karlsson F, et al. Altered microbiota in microscopic colitis. Gut 2015; 64: 1185–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Järnerot G, Tysk C, Bohr J, et al. Collagenous colitis and fecal stream diversion. Gastroenterology 1995; 109: 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagkalidis PP, Gibson PR, Bhathal PS. Microscopic colitis demonstrates a T helper cell type 1 mucosal cytokine profile. J Clin Pathol 2007; 60: 382–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumawat AK, Strid H, Tysk C, et al. Microscopic colitis patients demonstrate a mixed Th17/Tc17 and Th1/Tc1 mucosal cytokine profile. Mol Immunol 2013; 55: 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumawat AK, Strid H, Elgbratt K, et al. Microscopic colitis patients have increased proportions of Ki67+ proliferating and CD45RO+ active/memory CD8+ and CD4+8+ mucosal T cells. J Crohn’s Colitis 2013; 7: 694–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koskela RM, Karttunen TJ, Niemelä SE, et al. Human leucocyte antigen and TNFα polymorphism association in microscopic colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miehlke S, Heymer P, Bethke B, et al. Budesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 978–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baert F, Schmit A, D’Haens G, et al. Budesonide in collagenous colitis: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with histologic follow-up. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonderup OK, Hansen JB, Birket-Smith L, et al. Budesonide treatment of collagenous colitis: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial with morphometric analysis. Gut 2003; 52: 248–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miehlke S, Madisch A, Karimi D, et al. Budesonide is effective in treating lymphocytic colitis: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 2092–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pardi DS, Ramnath VR., Loftus EV, et al. Lymphocytic colitis: Clinical features, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2829–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miehlke S, Madisch A, Voss C, et al. Long-term follow-up of collagenous colitis after induction of clinical remission with budesonide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riddell J, Hillman L, Chiragakis L, et al. Collagenous colitis: Oral low-dose methotrexate for patients with difficult symptoms: Long-term outcomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 22: 1589–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotter TG, Kamboj AK, Hicks SB, et al. Immune modulator therapy for microscopic colitis in a case series of 73 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Münch A, Bohr J, Vigren L, et al. Lack of effect of methotrexate in budesonide-refractory collagenous colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2013; 6: 149–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Münch A, Fernandez-Banares F, Munck LK. Azathioprine and mercaptopurine in the management of patients with chronic, active microscopic colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esteve M, Mahadevan U, Sainz E, et al. Efficacy of anti-TNF therapies in refractory severe microscopic colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2011; 5: 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pola S, Fahmy M, Evans E, et al. Successful use of infliximab in the treatment of corticosteroid dependent collagenous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 857–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Münch A, Ignatova S, Ström M. Adalimumab in budesonide and methotrexate refractory collagenous colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012; 47: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hjortswang H, Tysk C, Bohr J, et al. Defining clinical criteria for clinical remission and disease activity in collagenous colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 1875–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis E, Mary J, Vernier–Massouille G, et al. Groupe D’etudes Thérapeutiques Des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Maintenance of remission among patients with Crohn’s disease on antimetabolite therapy after infliximab therapy is stopped. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 63–70.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigren L, Sjöberg K, Benoni C, et al. Is smoking a risk factor for collagenous colitis? Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 1334–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Münch A, Tysk C, Bohr J, et al. Smoking status influences clinical outcome in collagenous colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016; 10: 449–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]