Abstract

Background:

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common infectious diseases ranking next to upper respiratory tract infections. UTIs are often significantly associated with morbidity and mortality. The inappropriate administration of antibiotics to treat these infections increased infection resistance to antibiotics. The aim of this study is to determine the frequency of antibiotic resistance pattern in UTIs.

Methods:

We searched several databases including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, Iran Medex, Magiran, IranDoc, MedLib, and Scientific Information Database to identify the studies addressing antibacterial resistance patterns of the most common uropathogenic bacteria in UTIs in Iran. A total of 90 reports published from different regions of Iran from 1992 to May 2015 were involved in this study.

Results:

It is shown that the most common pathogen causing UTIs is Escherichia coli with 62%. The resistance among the isolates of E. coli was as follows: ampicillin (86%), amoxicillin (76%), tetracycline (71%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (64%), cephalexin (61%), and cefalothin (60%). The highest sensitivity among isolates of E. coli was as follows: imipenem (86%), nitrofurantoin (82%), amikacin (79%), chloramphenicol (72%), and ciprofloxacin (72%).

Conclusions:

The results of this study showed that the most common resistance are antibiotics that are commonly used. The most effective antibiotics for E. coli were imipenem, nitrofurantoin, amikacin, chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin. Considering this study, it had better, use less gentamicin, second-generation cephalosporins, and nalidixic acid in the initial treatment of infections caused by E. coli, and no use penicillins, tetracyclines, cotrimoxazole, and first-generation cephalosporins.

Keywords: Antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, urinary tract infections

Introduction

After respiratory infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs) as one of the most common bacterial infections are considered human. Several studies suggest that Gram-negative bacilli, including Enterobacteriaceae bacteria family, are the most common microorganisms in the appearance of UTIs. In the meantime, E. coli is causing more than 81% of cases of UTIs;[1,2] afterward, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Proteus, and Enterococci have identified as the causes of UTIs.[3] Quick and accurate diagnosis of UTI is very important to shorten the course of illness, as well as to prevent disease progression toward upper UTIs and renal impairment.[4] Resistances to antibiotics in different parts of the world due to genetic changes in strains, diversity in the use of antibiotics, and division in the availability to broad-spectrum of new antibiotics are different.[5] In many infectious diseases including UTIs, a physician needs to start the treatment before a definitive diagnosis of infection cause and antibiogram; therefore, to administer the appropriate antibiotic, the physician must have sufficient information about the probable cause of infection and antibiotic susceptibility;[6] hence, UTI agents and their antibiotic resistance are identified in each region to start treatment before culture and antibiotic sensitivity test results.[5,7] Studies to identify the pathogens responsible for UTIs and antibiotic resistance are significant to their specific therapy to eradicate the infectious agent.[8,9] According to the numerous studies in the field of bacterial drug resistance patterns of UTIs, for validating the results of this study to give more precise and valid results, the current study is carried out through systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

A database was built for the most common resistance pattern of bacteria that causes UTIs in Iran from 1991 to 2015 using internal and external databases, including Scientific Information Database, Magiran, IranDoc, IranMedex, MedLib, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Search was limited to research papers about the most common bacterial causing UTIs and their antibiotic resistance patterns that have published in Persian and English magazines. The keywords, titles, and abstracts were used by Boolean operator assistance. Keywords involved are UTIs, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance. Likewise, titles and search results were evaluated and their suitability was determined for potential inclusion in the study. Furthermore, the references of selected articles were examined. Related studies in the list of references for inclusion in the study were selected.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All cross-sectional or group studies were considered in relation to antibiotic resistance patterns of bacteria that cause UTIs. Study selection for inclusion in the assessment was done in three stages based on papers review: title, abstract, and full text. In some cases, due to ambiguity in the results of a study, the author should be contacted by for more information. Related studies involved the prevalence of bacteria causing UTIs and antibiotic resistance pattern. Studies excluded from the analysis in each of the following reasons: studies that had insufficient information, studies not included in epidemiological studies, studies not included in cross-sectional studies, and studies that have relation with other infections than UTIs. Furthermore, overview studies, summary of congresses, studies published in other languages except for Persian and Latin, systematic studies and meta-analyses, and repetitive publications were excluded from the analysis.

Data extraction

The data extracted from all studies were first author, publication year, study year, study location, sample size, average and age group, gender, type of insulation, urinary pathogen prevalence, bacterial factors, resistance to different antibiotics, antibiotic susceptibility test methods, and antibiotics susceptibility report criteria [Table 1]. Abstract and full-text search and examination were performed independently by two people, and if the results did not have any corresponding together, studies coexamined jointly to resolve the dispute.

Table 1.

General data and specifications reviewed articles in the meta-analysis

| First author | Publishing year | Study year | Location of study | Number of samples | The Prevalence of Pathogens (percent) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus | Enterobacter | Proteus | Pseudomonas | Acinetobacter | Citrobacter | Enterococci | Staphylococcus | Klebsiella | E. coli | |||||

| Molazadeh[74] | 1391 | 1383 | Western Azerbaijan | 1900 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 39.3 |

| Mohajeri[75] | 1390 | 1387 | Kermanshah | 1114 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 75 |

| Molazadeh[7] | 1393 | 91-92 | Fasa | 2484 | - | 5.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16.6 | 76.3 |

| Mosavian[76] | 1383 | 1382 | Ahvaz | 38 | - | 18 | - | 6 | - | - | - | 14 | 20 | 34 |

| Madani[77] | 1387 | 1358 | Kermanshah | 1815 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 45.4 | |

| Sorkhi[78] | 1384 | 1381 | Babol | 188 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59.5 | |

| Ghoutaslou[79] | 1384 | 91-92 | Tabriz | 213 | - | 5.2 | 9 | 4.2 | - | - | - | - | 10.3 | 79 |

| Norouzi[80] | 1379 | 1377 | Tehran | 313 | - | 1.6 | 12.7 | 5.9 | - | - | - | 3.2 | 4.6 | 53.5 |

| Alaie[81] | 1387 | 84-83 | Tehran | 510 | - | 2.4 | 7.6 | - | - | - | - | 6.1 | 9 | 72 |

| Torabi[82] | 1368 | 1385 | Zanjan | 118 | - | 3.9 | - | - | - | - | - | 15.9 | 17.3 | 48.4 |

| Hajizade[83] | 1382 | 1381 | Tehran | 150 | - | - | 4 | 5 | 8 | - | - | 19 | 10 | 50 |

| Eghbalian[84] | 1384 | 83-84 | Hamedan | 156 | - | 6.4 | 2.6 | - | - | 2.6 | - | 5.1 | 2.6 | 82 |

| Jarsiah[72] | 1393 | 90-91 | Tehran | 208 | - | - | 5.8 | 3.4 | - | - | - | 6.2 | 73.1 | |

| Mirmostafa[85] | 1392 | 1379 | Karaj | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | 3 | 83 | |

| Mobasher[86] | 1381 | 139 | Gorgan | 33 | - | - | 3 | 3 | - | 3 | - | 30.3 | 15.2 | 33.3 |

| Asgharian[87] | 1391 | 89-90 | Tenekanon | 307 | - | - | - | - | - | 84.6 | ||||

| Sharif[88] | 1378 | 74-76 | Kashan | 152 | - | 0.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14-Jul | 52 |

| Rahimi[89] | 1393 | 90-91 | Esfahan | 301 | - | 2.3 | 2 | 0.65 | 11.3 | 7.3 | 65.5 | |||

| Mokhtarian[90] | 1385 | 80-84 | GONABAD | 353 | - | - | 3.4 | - | - | - | - | 21.8 | 7.9 | 66 |

| Assefzadeh[91] | 1383 | 1386 | Ghazvin | 224 | - | 3.1 | 2.7 | 10.3 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 61.2 | |

| Tarhani[64] | 1382 | 80-81 | Khoram abad | 127 | - | 3.1 | 12.6 | - | - | 0.8 | - | - | 9.4 | 23.2 |

| Hamid-Farahani[92] | 1391 | 87-88 | Tehran | 456 | 8.6 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 3.3 | 22.1 | 13 | 60.3 |

| Mohammadi[93] | 1385 | 1380 | Falavarjan | 209 | - | 6.2 | 2.9 | 2.4 | - | - | 1.4 | 17.2 | 15.8 | 54.1 |

| Fahimi[94] | 1382 | 75-82 | Tehran | 120 | - | 0.5 | 1.1 | - | - | 2.8 | 2.9 | 61.1 | ||

| Saedi[95] | 1392 | 89-91 | Mashhad | 102 | - | - | - | 4.5 | 14.5 | - | 14.5 | 1.3 | 15.4 | 16.3 |

| Yazdi[96] | 1389 | 88-89 | Tehran | 444 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 55.4 |

| Yadollahi[97] | 1381 | 71-76 | Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari | 202 | - | 6.5 | 2.5 | 0.8 | - | - | - | 2.5 | 7.5 | 80 |

| Soleimani[98] | 1392 | 91-92 | Semnan | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70 |

| Moulana | 1392 | 87-88 | Babol | 770 | 12.1 | - | - | - | - | 5.9 | 8 | 17.9 | 48.6 | |

| Heidari-soreshjani[100] | 1392 | 90-91 | Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari | 74 | 4.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20.3 | - | 70.3 |

| Soltan Dallal[101] | 1390 | 88-89 | Tabriz | 400 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 47 | ||

| Yazdi[102] | 1392 | - | Tehran | 300 | 22.3 | - | - | - | - | - | 22.3 | 77.7 | ||

| Fesharakinia[103] | 1391 | 88-89 | Birjand | 100 | - | - | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 75 |

| Jalalpour[104] | 1388 | 1387 | Esfahan | 91 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15.4 | 84.6 | |

| Mohammadimehr[105] | 1390 | 86-87 | Tehran | 77 | - | 6.5 | 9.1 | 13 | 10.3 | 1.3 | - | - | 13 | 45.4 |

| Sahebnagh[106] | 1393 | 1392 | Tehran | 1123 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 |

| Safkhani[107] | 1393 | 1392 | Tehran | 136 | - | - | 4.4 | - | - | 1.5 | 8.8 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 51.5 |

| Soltan Dallal[101] | 1393 | 91-92 | Tehran | 400 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 24 | - |

| Asghari Moghadam[108] | 1393 | 89-90 | Tehran | 116 | - | - | - | 10.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mortazavi[109] | 1393 | 1391 | Yasouj | 200 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 61.5 | |||

| Asadi Manesh[5] | 1393 | 1391 | Yasouj | 145 | - | 3.5 | 6.2 | 2.8 | - | - | - | 3.4 | 10.3 | 72.4 |

| Dehbashi[110] | 1393 | 92-93 | Tehran | 522 | 10.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Savadkoohi[111] | 1392 | 89-90 | Babol | 128 | - | - | - | 4.1 | - | - | - | - | 3.1 | 8.9 |

| Sharif[112] | 1393 | 91-92 | Kashan | 180 | - | - | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 19.4 | 64.3 |

| Isvand[3] | 1393 | 1391 | Dezfool | 160 | 3.1 | 1.9 | - | 1.3 | - | 2.5 | - | 4.4 | 20.1 | 63.3 |

| Esmaeili[113] | 1392 | 90-91 | Hamedan | 141 | - | 10.7 | 7.1 | 7.9 | - | - | - | 8.5 | 61 | |

| Hosseini[114] | 1393 | 91-92 | Ghazvin | 12.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.6 | 61.1 |

| Shahraki[115] | 1393 | 1391 | Zahedan | 122 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.2 | - | |

| Bagheri[116] | 1393 | 90-91 | Gorgan | 111 | - | 26.1 | 6.3 | 13.5 | 1.8 | - | - | - | 40.5 | - |

| Molazade[117] | 1393 | 91-93 | Fasa | 283 | - | 5.7 | 5.7 | - | - | - | 6.4 | 14.5 | 64.3 | |

| Molazade[118] | 1393 | 91-92 | Fasa | 24-84 | - | 5.8 | 3.5 | 1.7 | - | - | - | - | 23.9 | 64.7 |

| Molaabaszadeh[119] | 1392 | 1390 | Tabriz Fasa | 5701 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 58.4 | |

| Farajnia[120] | 1388 | 86 | Tabriz | 676 | - | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.7 | - | - | 1.2 | 8 | 11.7 | 74.6 |

| Ahangarkani[121] | 1393 | 92-93 | Babol | 128 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 78 |

| Nasiri[122] | 1379 | 78-79 | Birjand | 111 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 65 |

| Savadkoohi[111] | 1386 | 82-83 | Babol | 160 | - | 11.9 | 3.1 | 6.3 | - | - | - | 6.5 | - | 70 |

| Panahi[123] | 1387 | 80-84 | Tehran | 28 | - | 17.9 | - | - | - | 17.9 | 43 | 21.4 | ||

| Esmaeili[124] | 1384 | 80-81 | Mashhad | 166 | - | 1.8 | 6 | 0.6 | - | 2.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 7.2 | 74.1 |

| Jalalpoor[125] | 1390 | 88-89 | Esfahan | 211 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | 64 |

| Jalalpoor[125] | 1390 | 88-89 | Esfahan | 167 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 52 |

| Zamanzad[126] | 1384 | 1383 | Shahre Kord | 100 | - | 2 | - | 6 | - | - | - | 12 | 38 | 42 |

| Zamanzad[126] | 1384 | 1383 | Shahre Kord | 100 | - | 6 | 4 | 2 | - | 1 | - | 7 | 16 | 58 |

| Norouzi[127] | 1385 | 1 | Jahrom | 351 | - | 3.7 | 56 | 1.4 | - | 1.2 | - | 0.84 | 10.7 | 80.3 |

| Abdolahi[128] | 1383 | 86-87 | Tehran | 5400 | 15.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | - | - | 0.8 | 2 | 14.1 | 8.8 | 44.5 |

Statistical analysis

With regard to the prevalence of antibiotic resistances and sample numbers that were obtained in each article, for calculating the variance of each study and combined with the amounts of various studies, the prevalence of binomial distribution and weighted average were used, respectively. However, weight was given to each study proportional to its variance inverse. Due to the large difference in prevalence in different studies (heterogeneity in studies) and know the significance of the homogeneity index (I2), the random-effects model was used in the meta-analysis.

Results

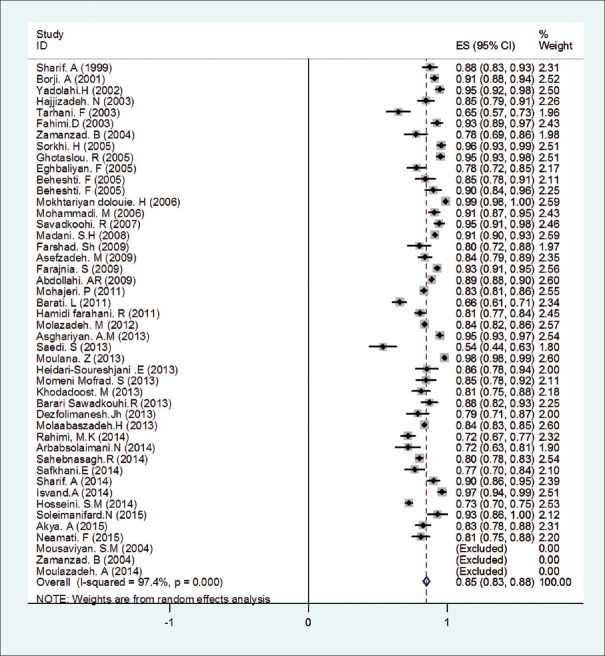

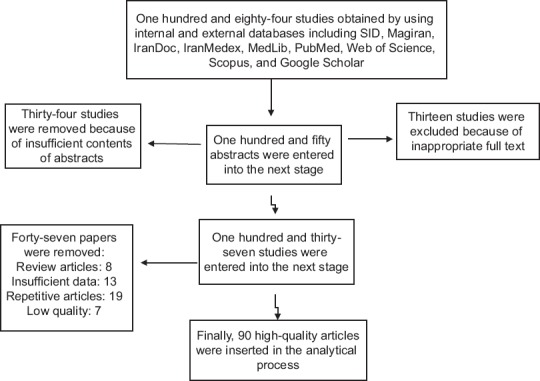

As a result of the initial search, 184 articles were obtained. In the next stage, 34 articles were rejected based on titles and abstracts assessment and the full-text 150 articles remained were studied. After this, 137 papers were selected to be involved the next stage. Then, 47 articles were eliminated (8 reviews, 19 duplicates, 7 low-quality articles, and 13 articles due to insufficient information). Finally, after a precise review of selected articles, 90 studies conducted in 1991–2015 have been entered in the meta-analysis [Figure 1]. General specifications and data sheet are depicted in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Studies entry to systematic review and meta-analysis

In reviewing studies in this meta-analysis, by a total number of urine samples collected in national and private laboratories, based on standard methods, 35,118 people with UTI (65.37% female and 34.63% male), also 78.40% of urinary infections were common outpatient and hospitalized patients were 21.60%.

Among the most common pathogens causing UTIs were E. coli, Klebsiella, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus with a frequency of 62%, 13%, 12%, and 11% took place the next ranks, respectively [Figure 2]. Other bacteria Enterococcus, Citrobacter, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Proteus, and Enterobacter had a marginal role in UTI with the frequency of 2% [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Resistances rate of Escolar isolates to Ampicillin based on a random-effects model. The midpoint of each piece represents an estimate of the prevalence, each piece represents a confidence interval of 15% in each study and diamond mark is indicative of all the studies in the whole country

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of bacteria causing UTIs examined in the meta-analysis

| P | Heterogeneity index I2 (%) | Confidence interval (CI%95) | Prevalence | The number of studies | Bacteria type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <.001 | 97.9 | 58-65 | 62% | 58 | E. coli |

| <.001 | 95.6 | 11-15 | 13% | 44 | Klebsiella |

| <.001 | 98 | 0.09-15 | 12% | 32 | Staphylococcus |

| <.001 | 96 | 0.06-16 | 11% | 6 | Streptococcus |

| <.001 | 91.5 | 0.04-0.07 | 05% | 12 | Enterococcus |

| <.001 | 26.4 | 0.01-0.02 | 01% | 14 | Citrobacter |

| <.001 | 79.6 | 0.03-10 | 06% | 5 | Acinetobacter |

| <.001 | 72.8 | 0.02-0.04 | 03% | 28 | Pseudomonas |

| <.001 | 82.6 | 0.03-0.04 | 04% | 28 | Proteus |

| <.001 | 93 | 0.04-0.07 | 05% | 28 | Enterobacter |

| <.001 | 91.6 | 1.2-2.4 | 1.76 | 15 | Other Species |

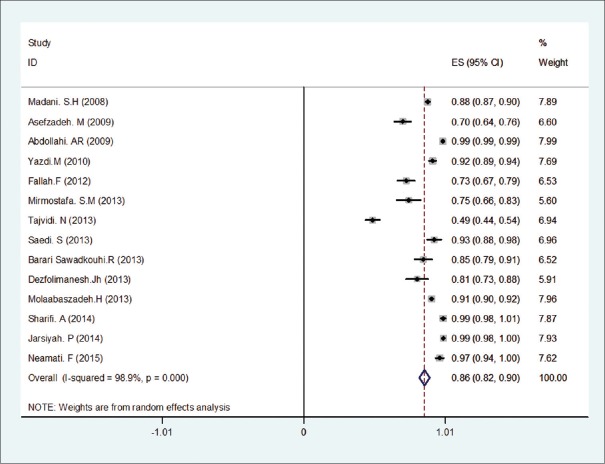

Resistance of E. coli to different antibiotics in the included studies at meta-analysis is summarized in Table 3. The analysis results of the most common resistance isolates causing UTIs to antibiotics are given in Table 4. As it can be seen, there is most resistance among E. coli isolates to ampicillin (86%) [Figure 2], amoxicillin (76%), tetracycline (71%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (64%), cephalexin (61%), and cefalothin (60%) antibiotics. Likewise, the lowest rate of resistance had been observed in imipenem (14%) [Figure 3], nitrofurantoin (18%), amikacin (21%), chloramphenicol (28%), and ciprofloxacin (28%) antibiotics, and the resistance of E. coli isolates as compared to other used antibiotics was as follows: gentamicin (32%), ceftriaxone (35%), cefazolin (48%), cefixime (45%), nalidixic acid (43%), cefotaxime (42%), and ceftazidime (40%).

Table 3.

E. coli resistance rate (%) to different antibiotics in the articles reviewed in the meta-analysis

| First Author | Chloramphenicol | Nitrofurantoin | Imipenem | Cefalotin | Cephalexin | Cefixime | Cefotaxime | Ceftriaxone | Ceftazidime | Nalidixic acid | Ciprofloxacin | Amikacin | Gentamicin | Tetracycline | Amoxicillin | Ampicillin | Cotrimoxazole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molazadeh[74] | - | 5.5 | - | 48.9 | - | - | - | - | - | 24.8 | 19 | - | 11.5 | - | - | 84 | 60.3 |

| Mohajeri[75] | - | 6.7 | - | 52 | 45.9 | 28.6 | 24.8 | 29 | 24.2 | 43.2 | 30.1 | 4.7 | 14.8 | 74.2 | 86 | 83.4 | 58.7 |

| Molazadeh[7] | - | 11.9 | - | 49 | - | 43.4 | - | 40 | - | 56 | 30.9 | - | 31 | - | - | - | 59.4 |

| Mosavian[76] | 47.1 | 29.8 | - | - | 94.1 | - | - | - | - | 11.8 | - | - | 23.5 | - | - | 100 | 35.3 |

| Madani[77] | - | 8.5 | 11.8 | 66.7 | 41.4 | 46.8 | 30.4 | 29.8 | 38.8 | 38.5 | 25.5 | 32.3 | 43.3 | - | - | 91.4 | 61.1 |

| Sorkhi[78] | - | 30 | - | - | 86 | - | - | 6 | - | 20 | - | 7.5 | 18.5 | - | - | 91 | 81 |

| GHoutaslou[79] | - | 26.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22.5 | 4.3 | 18.3 | 40 | - | - | 95.5 | 64.7 |

| Nourozi[80] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 78.1 |

| Alaie[81] | - | 20.6 | - | - | 62.8 | - | - | 17.2 | - | 16.4 | 9 | 6 | 15.4 | - | - | 78.9 | 66 |

| Torabi[82] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 57.4 |

| Hajizadeh[83] | - | 88 | - | 656 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | - | - | 50 | 85 | 72 |

| Eghbalian[84] | - | 12.5 | - | - | - | - | - | 34.4 | - | 25 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 25 | 75 | - | 78.1 | 34.4 |

| Jarsiah[72] | - | 0.7 | 0 | - | - | 33.1 | - | - | 34.7 | 55.8 | 28.2 | 9.1 | 14.9 | - | - | - | 65.5 |

| Mirmostafa[85] | 16.9 | 8.4 | 25.3 | 48.2 | 61.5 | - | 38.5 | 37.3 | 27.7 | 56.6 | 32.5 | 18 | 28.2 | 63.6 | 83 | - | 59 |

| Asgharian[87] | - | 63 | - | 76 | - | 97 | 97 | 64 | 99 | 84 | 52 | 81 | 54 | 91 | 96.5 | 95 | 83 |

| Sharif[88] | - | - | - | 51.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 87.7 | 56.3 |

| Rahimi[89] | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | 31 | 32 | - | 73 | 1 | - | 28 | - | - | 72 | 70 |

| Mokhtarian[90] | - | 39.3 | - | - | 73 | - | - | - | - | 44.6 | 9.4 | 36.9 | 50.2 | - | 100 | 99.1 | 62.2 |

| Assefzadeh[91] | - | 27.6 | 29.6 | - | - | - | - | 46.7 | - | - | 46.7 | 28 | 42 | - | - | 84.2 | 61.5 |

| Tarhani[64] | - | 11.8 | - | - | - | 4.7 | - | 3.1 | - | 7.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 9.4 | - | 63 | 65 | 54.3 |

| Hamid-Farahani[92] | - | 5 | - | - | - | 25.6 | - | - | - | - | 21.3 | - | 27.7 | - | - | 80.7 | 37 |

| Mohammadi[93] | 23.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 87.9 | 8.3 | 31.1 | 6.9 | 44.8 | 91 | 91 | 63.4 |

| Fahimi[94] | - | 5.9 | - | - | 37.1 | - | - | 2.9 | - | 5.9 | - | 5.9 | 11.8 | - | - | 92.9 | 75.3 |

| Saedi[95] | - | 7.6 | 7.2 | - | - | - | - | 38.4 | 38.4 | - | 15.3 | 7.6 | 23 | - | - | 53.8 | - |

| Yazdi[102] | - | - | 8.3 | - | - | - | 39.2 | - | 47.1 | 50 | 33.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yadollahi[97] | - | 40 | - | - | 95 | - | - | - | - | 68 | - | 80 | 6.9 | - | 9.5 | 95 | - |

| Soleimani[98] | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22 | 0 | 18 | - | - | 72 | 42 |

| Moulana[99] | - | 17.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21.7 | - | - | 98.4 | 69.3 |

| Heidari-soureshjani[100] | - | 5.2 | - | - | - | 37.5 | - | 43.9 | - | 78.8 | 46.5 | 7.7 | 10 | - | - | 85.7 | 42.4 |

| Soltan Dallal[101] | 14 | - | - | - | - | - | 43 | - | 42 | 35 | 56 | - | 29 | - | 82 | - | 65 |

| Fesharakinia[103] | - | 26.2 | - | - | 51.7 | 23.1 | - | 23.9 | 25.8 | 33.8 | - | - | 20.9 | - | - | - | 69.9 |

| Jalalpour[104] | - | 16.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 19.5 | 54.9 | 30.3 | - | 27.8 | - | - | - | 59.2 |

| Sahebnagh[106] | - | 2.2 | - | - | - | - | - | 42.5 | 27.3 | - | 48.7 | 0.5 | 24.1 | - | - | 80.3 | 61.4 |

| Safkhani[107] | - | 1.4 | - | - | - | - | - | 34.8 | 27 | - | 17.9 | 2.9 | 18.2 | - | - | 76.8 | 60 |

| Mohammadimehr[105] | - | - | - | - | - | - | 39 | - | 17.9 | 51.2 | 22.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Savadkoohi[111] | - | 7.6 | 15 | - | 49 | 35 | 28 | 35.4 | - | 51 | 28 | 9.5 | 19 | - | - | 87.5 | 62.3 |

| Sharif[112] | - | 49.1 | - | - | 78.9 | 54.4 | - | 41.2 | - | 25.4 | - | - | - | - | 88.6 | 90.4 | - |

| Isvand[3] | - | 11.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34.7 | 11.3 | - | 17.7 | - | - | 96.6 | 11.2 |

| Esmaeili[113] | - | 2.3 | - | - | - | - | - | 46.5 | - | 1.2 | 24.4 | - | 17.4 | - | 90.7 | - | 28 |

| Hosseini[114] | - | 23 | - | - | - | - | 18.6 | - | 25 | 46.6 | 15.9 | 20 | 22 | - | 79.9 | 72.6 | 48 |

| Molazade[117] | - | 21.5 | - | 62.3 | - | 57.2 | - | 43.5 | - | 52.4 | 17.2 | - | 31.4 | - | - | - | 66.5 |

| Molazade[118] | - | 16.4 | - | 64.1 | 69.6 | 61.6 | 66.7 | 56.6 | - | 66.8 | 36 | 10.2 | 34.4 | 62.1 | - | 100 | 68.7 |

| Molaabaszadeh[119] | - | 11 | 8 | - | - | - | 26.7 | 33 | - | 44 | 27 | 32 | 43.1 | 81 | - | 84 | 63.9 |

| Farajnia[120] | - | 12.9 | - | - | 24 | - | - | - | - | 6.3 | 6 | 2.2 | 3 | - | - | 93.1 | - |

| Ahangarkani[121] | - | - | - | - | - | 34 | - | - | - | - | 34 | - | - | - | - | - | 67 |

| Nasiri[122] | - | - | - | - | 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 86 | - | 65 |

| Savadkoohi[111] | - | 21.4 | - | - | 54.5 | - | - | 17.9 | - | 25 | - | 6 | 17 | - | - | 94.6 | 67 |

| Esmaeli[124] | - | 3.3 | - | 0 | 20.8 | 2.5 | 0 | 15 | - | 17.4 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 5.2 | - | - | - | 75.8 |

| Zamanzad[126] | - | 62 | - | 62 | - | - | - | - | - | 57 | - | - | 81 | - | - | 100 | 76.2 |

| Zamanzad[126] | - | 17.2 | - | 43 | - | - | - | - | - | 17.2 | - | - | 36.2 | - | - | 77.6 | 65.5 |

| Norouzi[127] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28.7 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 28.1 | - | - | - | 51 |

| Abdolahi[128] | - | 6 | 1 | - | - | - | 41 | - | - | - | - | 32 | 28 | - | - | 89 | - |

| Sharifi[129] | 7.5 | - | 0.8 | 100 | - | - | - | - | 41.6 | 48.3 | 28.3 | 5 | 20.8 | 55 | 76.6 | - | 62.5 |

| Borji[130] | - | 17.1 | - | - | - | - | - | 2.5 | - | 21.2 | 9.4 | - | 24.8 | - | - | 91.1 | 80.5 |

| Barati[131] | - | 3 | - | - | 23.6 | - | - | 13.5 | - | 28.6 | - | - | 8.9 | - | 53.4 | 65.9 | 47 |

| Farshad[132] | 35.4 | 3.1 | - | - | - | 19.7 | - | - | 10.4 | 25 | 8.3 | 3.1 | 15.6 | 70.8 | - | 80.2 | 76 |

| Tajvidi[133] | - | - | 29 | - | - | 39 | - | 30 | - | - | 30 | - | 22 | - | - | - | 51 |

| Ranjbaran[134] | 56 | 18 | - | - | - | - | 73 | 76 | 72 | - | 29 | 27 | 74 | 60 | 74 | - | 88 |

| Beheshti[135] | - | 1 | - | 47.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 33 | 26.2 | - | 16.4 | - | - | 84.5 | 64.1 |

| Beheshti[135] | - | 2.9 | - | 51 | - | - | - | - | - | 45.1 | 32.4 | - | 18.6 | - | - | 90.2 | 71.6 |

| Babaie[136] | - | 20 | - | - | - | 93.3 | - | 100 | 83.3 | - | 83.3 | 13.3 | 63.3 | 86.7 | 96.7 | - | 93.3 |

| Tashkori[137] | - | 12.3 | - | 58.9 | - | - | 28.1 | 30.1 | 27.4 | 39.7 | 21.9 | - | 15.6 | - | - | - | 62.3 |

| Momeni mofrad[65] | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | - | 55 | 1 | 39 | - | - | 85 | - |

| Naghavi[138] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 52 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nateghian[139] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 38.4 | - | - | - | - | 24 | - | - | - | - |

| Zibaei[140] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 82.8 | 43 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fallah[141] | 49 | 33.5 | 27.1 | 60 | - | - | - | - | 38.1 | 57.4 | 36.2 | 32.1 | 46.4 | - | 78 | - | 67.7 |

| Khodadoost[142] | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | 24.3 | 15.7 | - | 31.4 | - | 16.4 | - | - | 81.4 | 62.1 |

| Ghadiri[143] | - | - | - | - | - | 35.6 | - | 39.1 | - | 44.8 | - | 14.9 | 20.7 | - | - | - | 72.4 |

| soleimaifard[144] | - | 3.3 | - | - | - | 53.3 | - | 56.7 | - | 73.3 | 40 | 0 | 16.7 | - | - | 93.3 | - |

| Akya[145] | - | - | - | - | - | - | 46 | 45.2 | 26.1 | - | 37 | - | 24.7 | - | - | 83 | 57.5 |

| Dezfolimanesh[146] | - | - | 12.5 | - | - | - | 49.7 | 49.7 | 35.9 | - | 34.1 | 11.2 | 36.8 | - | - | 79.1 | 55.6 |

| Sedighi[147] | - | 6 | - | - | - | 44 | - | - | - | 60 | - | 2 | 18 | - | - | - | 70 |

| Neamati[148] | - | 17.3 | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | 56.7 | 49.3 | 71.3 | 61.3 | - | 40 | - | 16 | 81.3 | 64.7 |

| Sedighi[149] | - | 0 | - | - | - | 35 | - | 30 | - | 47 | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | 70 |

| Emam[150] | 13.3 | 34.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21.6 | 6.7 | 28.6 | 72.1 | - | - | - | 71.4 |

| Sedighi[149] | - | 0 | - | - | - | 35 | - | 30 | - | 47 | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | 7700 |

| Erfani[151] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 33.2 | - | 43.6 | - | 22.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Nakhaiemoghadam[152] | - | 1.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34.9 | 21.1 | - | 12.8 | - | - | - | 55.1 |

Table 4.

Sensitivity and resistance rate to different antibiotics in selected studies to the meta-analysis

| Antibiotic | Staphylococcus | Klebsiella | E. coli | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | Sensitivity | Resistance | Sensitivity | Resistance | Sensitivity | |

| Cotrimoxazole | 58 | 42 | 54 | 46 | 64 | 36 |

| Ampicillin | 87 | 13 | 80 | 20 | 85 | 15 |

| Amoxicillin | - | - | 76 | 24 | 76 | 24 |

| Tetracycline | - | - | 53 | 47 | 71 | 29 |

| Gentamicin | 49 | 51 | 38 | 62 | 32 | 68 |

| Amikacin | 41 | 59 | 27 | 73 | 21 | 79 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 20 | 80 | 19 | 81 | 28 | 72 |

| Nalidixic acid | 51 | 49 | 33 | 67 | 43 | 57 |

| Ceftazidime | - | - | 40 | 60 | 40 | 60 |

| Ceftriaxone | 66 | 34 | 40 | 60 | 35 | 65 |

| Cefotaxime | - | - | 38 | 62 | 42 | 58 |

| Cefixime | - | - | 53 | 47 | 45 | 55 |

| Cephalexin | 72 | 28 | 67 | 33 | 61 | 39 |

| Cefalotin | 43 | 57 | 55 | 45 | 60 | 40 |

| Imipenem | - | - | 13 | 87 | 14 | 86 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 42 | 58 | 42 | 58 | 18 | 82 |

| Chloramphenicol | - | - | 47 | 53 | 28 | 72 |

Figure 3.

Resistances rate of E.coli isolates to Imipenem based on a random-effects model. The midpoint of each piece represents an estimate of the prevalence, each piece represents a confidence interval of 15% in each study and diamond mark is indicative of all the studies in the whole country

In examining Klebsiella isolates, the lowest level of resistance to imipenem (13%), ciprofloxacin (19%), and amikacin (27%) were found. The resistance rate of Klebsiella isolates to other antibiotics was as follows: cefalothin (55%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (54%), tetracycline (53%), cefixime (53%), chloramphenicol (47%), nitrofurantoin (42%), ceftazidime (40%), ceftriaxone (40%), gentamicin (38%), cefotaxime (38%), and nalidixic acid (33%). In Staphylococcus isolates, the highest rate of resistance to ampicillin (87%), cephalexin (72%), and ceftriaxone (66%) antibiotics and the lowest rate of resistance to ciprofloxacin (20%) antibiotic was observed; furthermore, a resistance rate had also been seen in antibiotics of sulfamethoxazole (58%), nalidixic acid (51%), gentamicin (49%), cephalothin (43%), nitrofurantoin (42%), and amikacin (41%).

Discussion and Conclusions

In the current study, the prevalence rate of UTI in women was several times more than men (women,65.37% and men, 34.63%). In studies conducted in other parts of the world such as New York,[10] America,[11,12] Washington,[13] Portugal,[14] Mexico,[15] Nigeria,[16,17] Taiwan,[18] India,[19] and Pakistan,[20] the incidence of UTIs in women also was higher. The results of these studies are consistent with the results of our study, due to anatomical differences between men and women, including a short urethra and its external opening adjacent to the vagina and anus in women.[21,22]

The current study showed that Enterobacteriaceae family bacteria are the most common causes of UTIs; due to the presence of these bacteria in the digestive tract, a possible UTI may occur.[9] In the present study, E. coli was the most common pathogen that causes UTI; this result has to correspond to more studies in other parts of the world. E. coli prevalence reported 50%–80% in Asia (58% in Saudi Arabia,[23] 70% in India,[19] 75.3% in Turkey,[24] 65.9% in South Korea,[25] 74.8% in Bangladesh,[26]), 60.29% in Africa[27], 90%–-60% in Europe (64.5% in Portugal[14] and 85.9% in Russia[28]) 90%–75% in the USA,[29] and 76.6% in Brazil.[30] E. coli in the current and mentioned studies is the most common pathogen causing UTIs.

In other articles, other pathogens that cause UTIs more than E. coli have also been mentioned. In our study, Klebsiella was the second most common cause of UTIs; this result is consistent with the studies conducted in Australia,[31] South Africa,[32] Taiwan,[18] Bangladesh,[26] Pakistan,[20] and India.[33] However, in the studies conducted in South Korea and Europe, this had been reported that Enterobacter is the second UTI factor after E. coli.[25,34] In a study in Portugal on Enterobacter and Klebsiella bacteria, it has found that both bacteria have the same effect on UTIs after E. coli.[14] In regard to carried study in France, in urinary infections after E. coli, Gram-positive cocci were the most common cause of infection.[35] According to the current study and noted articles in this context, it is reported that the bacteria causing UTIs are approximately the same in the world. In general, E. coli are the most common bacteria. Then, Klebsiella, Staphylococcus, Enterobacter, and other species with slight differences in different geographical locations in the next category are placed. The resistance rate of E. coli and Staphylococcus ampicillin was 86% and 87%, respectively. In a study in South Korea, the resistance rates of E. coli and Klebsiella isolates to ampicillin were 6.63% and 99%, respectively.[25] In the same study in Taiwan, the rates of resistance in E. coli and Klebsiella were 100% and 70%, respectively.[18] E. coli resistance to ampicillin in studies conducted in Bangladesh was 80%,[36] Ethiopia 80%,[27] Mexico 79%,[37] UAE 72%,[38] Brazil 55%,[39] Turkey, 74%,[40] Greece 50%,[41] and America 48%.[42] Studies in North America, Canada, and Lebanon have reported similar results.[43,44,45] In the present and cited studies, the abundance of resistance to ampicillin was higher than other antibiotics. However, in the cited cases, as it can be seen, countries such as America, Brazil, and Greece had a lower rate of resistance than this study. The results of these studies suggest that antibiotics such as ampicillin are practically useless and even recommended not to be used for antibiogram.

In this study, the resistance rate of E. coli after ampicillin compared with amoxicillin (76%) and tetracycline (71%) higher. In a study in Ethiopia, the sensitivity of E. coli to amoxicillin was 15.4%, tetracycline was 17.8%, and ampicillin was 20%; for Klebsiella, it has been reported 30% to amoxicillin, 34.6% to tetracycline, and 8.1% to ampicillin.[26] In the same study as the current one, almost total resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, and tetracycline in the aforementioned isolates exists. The resistance to amoxicillin in urinary tract pathogens is similar to other studies that have conducted in other parts of the world, for example, the E. coli resistance to these antibiotics has been reported to be 85% in Ethiopia,[26] 67.5% in Senegal,[46] and 72% in India.[47] In Turkey, the rate of this resistance in separate studies had increased from 32.7% to 50% in 2009 and 2013.[24,48] In a Spanish study, E. coli antibiotic resistance at 2005, 2009, and 2011 was examined; the results showed that resistance to amoxicillin had increased from 4.5% in 2005 to 55.6% in 2011.[49] In a study in European countries, the resistance rate to amoxicillin was reported to be 48% in Poland and 60% in Belgium.[50] In all of these studies, the higher resistance to amoxicillin had reported, although the results of the current study similar to developing countries. Resistance to tetracycline in E. coli and Klebsiella isolates in Ethiopian[27] and Senegal[46] studies was similar to the present study. In this study, amoxicillin and tetracycline were taking place in another group of ineffective drugs. The reason for such resistance may be the somewhat irregular use of medication among patients, whether by prescription or willfulness, so they are not recommended as a treatment for UTI.

Cotrimoxazole is another antibiotic that is prescribed for UTI treatment. According to the results, all of the studied bacteria were resistant to the cotrimoxazole. E. coli resistance to cotrimoxazole in most developing countries illustrates similar results. For example, the rate of this resistance was 68.1% in Senegal,[46] 58% in Turkey,[24] and 53% in Lebanon.[45] Unlike the results of this study, some studies, especially that conducted on isolates of E. coli in developed countries, have reported low resistance to cotrimoxazole. For example, the rate of resistance in the studies conducted in Italy,[51] Canada,[44] Croatia,[52] America,[43] and Australia[31] was reported to be 27.1%, 22%, 20.59%, 21.3%, and 14.5%, respectively.

In the current study, based on resistance rate to antibiotics tetracycline and cotrimoxazole in uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), it can be said that the antibiotic resistance rate of in Iran is higher than some developed countries. This difference may be due to the strains of microorganisms, self-medication by patients, incomplete treatment course, prescribe inappropriate antibiotics by physicians, the dosage of medication, manufacturer-based drug quality, relying on empirical treatment regardless of culture and antibiotic susceptibility test results. Therefore, strict measures of clinical practitioners should be put at the head of affairs, for infection control and prevention from resistance spread.

Furthermore, in the present study, quinolone family antibiotics such as nalidixic acid ( first generation) and ciprofloxacin (second generation) were studied. In this study, resistance rates to nalidixic acid in E. coli, Klebsiella, and Staphylococcus were reported as 43%, 33%, and 51%, respectively, which shows the relatively high resistance. Regarding the past nalidixic acid in the first step used in treating UTIs, therefore, higher resistance is expected to these antibiotics than the other quinolone family antibiotics[51] that correspond with the findings of our study in this case. In Ethiopia, E. coli sensitivity rate to nalidixic acid, 86% reported[27] that toward the present study is higher but in Bangladesh has the lowest sensitivity (27%);[36] likewise, in Pakistan, resistance to nalidixic acid in urinary isolates of E. coli, 84.16% reported.[53] The results of these two studies are very different from the current study results that may be produced by overuse of cited drugs in developing countries without exact surveillance.

The high sensitivity to ciprofloxacin in all isolates (E. coli 72%, Klebsiella 81%, and Staphylococcus 80%) had been found. E. coli resistance to ciprofloxacin in the most done studies by other researchers reported, for example, resistance rates in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Senegal, India, South Korea, Turkey, Mexico, America, North America, Canada, Italy, and Germany about 5.5%–31.9%.[24,25,27,43,44,46,51,54,55,56,57,58] The resistance rate in urinary isolates of E. coli to ciprofloxacin in studies done in Pakistan and Bangladesh[36,53] was medium while in Lebanon with a frequency of 54% was too high. In this study, like many other studies, it has been determined that urinary tract pathogens have high sensitivity to quinolones and particularly ciprofloxacin that can be used as the first drug in the treatment of patients with UTI.[59] In Talon et al.'s study, fluoroquinolones had been recommended for the uncomplicated UTI treatment, especially when resistance to cotrimoxazole in a society does not exceed from 20% to 10%.[60] In general, this study illustrates that ciprofloxacin still can be used as the first-line therapy of UTIs in Iran.

Aminoglycosides are another group of antibiotics that are used in UTIs. In this study also, isolates resistant to amikacin and gentamicin were evaluated in this category. Resistance to amikacin in E. coli 21%, Klebsiella 27% and Staphylococcus 41% reported. Resistance to gentamicin in E. coli, Klebsiella, and Staphylococcus was reported to be 32%, 38%, and 49%, respectively. In most studies similar to our study, high sensitivity to amikacin was reported in UPEC. For example, E. coli sensitivity to amikacin in India was found to be 90.6%,[61] Saudi 93.7%,[61] South Korea 99.4%,[25] and Taiwan 100%.[18] Similarly, E. coli resistance to amikacin in Brazil was found to be 2%,[39] America 0%,[42] and China 11.7%.[62] In a study conducted in North America and Europe, E. coli sensitivity to amikacin was found to be about 98.5%–97.8%.[63] Klebsiella sensitivity to amikacin in South Korea was reported to be 95%[25] and Taiwan 100%,[18] which is consistent with our results.

In this study, founded relatively high sensitivity to gentamicin in E. coli, but sensitivity to gentamicin in Staphylococcus and Klebsiella obtained the average. E. coli sensitivity to gentamicin in South Korea was reported as 74.2%,[25] Taiwan 77%,[18] and Ethiopia 66%.[27] Likewise, in the study conducted in Europe, the resistance of E. coli to aminoglycosides was reported to be about 4.21%–5.2%.[64] These results are consistent with the results of our study. Klebsiella sensitivity to gentamicin in both South Korea[25] and Taiwan 95%[18] that toward to our study was higher, but in Ethiopia, 57.1% was reported,[27] which corresponds to the results of this study. In a study in China, most E. coli isolates resistance to gentamicin (95.1%) was also reported.[62] The reasons for the difference in the frequency of resistance to aminoglycosides in above studies than ours can be the various distributions of resistance genes in different geographical areas, consumption of antibiotics, and prescribing pattern. Gentamicin is one of the drugs that can be used as initial treatment of UTIs until the culture results prepared. One of the interesting features about old antibiotics such as gentamicin and amikacin is good penetration into the bacteria cell.[65] however, due to the increased use and availability of gentamicin, its resistance is greater than other aminoglycosides in many regions, and on the other hand, less resistance to amikacin, the frequency of resistance to these effective and inexpensive drugs varies from region to region. For these reasons, antimicrobial susceptibility testing required before treatment. The results of this study showed that amikacin could be used as the first-line therapy for the treatment of UTIs in Iran. However, in the case of gentamicin, since the resistance rate of these organisms to gentamicin in the present study obtained as 32%–49%, it is a kind of alarm for the spread of organisms resistant to these antibiotics and is recommended to be taken with caution.

In the present study, cephalexin and cefalotin (the first generation of cephalosporins) investigated. All isolates causing UTI were resistant to cephalexin. E. coli also had a high resistance to cefalotin, but Klebsiella and Staphylococcus had an intermediate resistant to these antibiotics. Furthermore, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, and cefixime (third-generation cephalosporins) investigated. The resistance rate of studied isolates to these group antibiotics was 65%–55%. Ethiopian,[27] Senegal,[46] and Lebanon[45] studies were consistent with the current study in this case. In these studies, intermediate resistance has reported in isolates of Escherichia to cephalosporins, but in the study of Taiwan, high sensitivity was observed in E. coli (cefazolin 81%, ceftriaxone 74%, and ceftazidime 89%) and also in isolates of Klebsiella (cefazolin 80%, ceftriaxone 85%, and ceftazidime 83%);[18] in South Korea, high sensitivity to cephalosporins was observed in E. coli (cefotaxime 89.4%, ceftazidime 89.2% and cephalotin 58.4%) and in Klebsiella (cefotaxime 78.8%, ceftazidime 77.8%, and cephalotin 70.5%)[25] has reported. A conducted study in Europe suggested E. coli resistance to the third generation of cephalosporins was around 19.2%–1.8%[64] and also low resistance has reported to these antibiotics in America.[57] In more advanced countries that have better performance in health and planning level, resistance to these antibiotics is less than Iran. Furthermore, in Greece, resistance to cefotaxime and ceftazidime 3.7% and 4% has been reported, respectively.[66] The different results of these studies than current study could be more accurate monitoring programs in that country and the unavailability of these drugs. This pharmaceutical group is the most common drugs in the treatment of infections, due to the high function and a wide range effect, but the results of this study and other studies indicative increasing resistance to these drugs in our country. In many countries such as Iran, this family of antibiotics is suitable as antimicrobial agents used in the treatment of UTIs, and this could be one of the main reasons for resistance to these antibiotics. Therefore, to avoid increasing resistance to this antibiotic group being used with caution and intransitive proceedings should be done.

In the present study, isolates were most sensitive to imipenem (86% in E. coli and 87% in Klebsiella). E. coli sensitivity to imipenem in Taiwan was 100%,[18] South Korea 100%,[25] India 98.89%,[55] Saudi Arabia 91.71%,[61] Turkey 93%,[24] and Europe and North America 99.7% and 99.8%,[63] respectively. Likewise, Klebsiella sensitivity to imipenem in Taiwan[18] and South Korea both was 100%[25] that these results were consistent with the results of this study. As mentioned above, the most effective antimicrobial agent was imipenem in this study that was consistent with the results of previous studies. This resistance reduction could be due to the limitation of drug usage in nosocomial infections, lack of necessary conditions (intravenous injection) in UTIs treatment in outpatients, lack of access to this drug, as well as being more expensive in compared with other drugs.[67]

In E. coli, highest sensitivity obtained to nitrofurantoin 82% after imipenem, but moderate sensitivity to these antibiotics was observed in Staphylococcus and Klebsiella isolates (58% each). In the United Kingdom[68] and extensive studies conducted in both America and Canada, very low resistance prevalence has been reported in urinary isolates of E. coli to nitrofurantoin (1.1% and 4%).[43,44] In studies conducted in China and Saudi Arabia, E. coli resistance rate to nitrofurantoin was 8% and 6.5%–2.4% reported, respectively.[69,70] The sensitivity of E. coli to nitrofurantoin in Ethiopia was 89.6%[27] and India 77.4% reported.[19] These studies are consistent with the present study. In this study, E. coli has a high sensitivity to chloramphenicol (72%), which is consistent with other studies.[19,24,27] According to the results of this study, the use of imipenem and nitrofurantoin antibiotics suggests because of their positive role has been evaluated by various articles. The UTIs are the most common infections seen in all parts of the world. However, the infection is not threatening, but if specific therapy is done, its side effects can be very severe.[21,71,72] The initial treatment of the infection is often experimental, and antibiotics selection depends on various factors such as intensity of symptoms, drug toxicity, and the effectiveness of treatment; however, the common types of urinary pathogens in the community and their susceptibility antimicrobial patterns are effective in antibiotic selection.[73] It is noteworthy that this antibiotic resistance of these bacterial agents is different in diverse parts of the world. Hence, in the treatment of urinary infections, antibiotic selection should be based on knowledge of the region, and international reports are not an appropriate choice for antimicrobial drug selection.[68,74] Due to the additive prevalence of resistance to antibiotics, early and timely diagnosis of the resistant bacterial isolates is considered necessary, to select appropriate treatment options and prevent the proliferation of resistance.

Limitations

The limitations of this study were the lack of resistance rate estimation in urinary uropathogenic for all antibiotics used in Iran, due to the lack of information in this field of compiled researches. Nonentity of calculation for antibiotic resistance rate in isolates that cause UTIs in males and females separately is one of the limitations of this study because only a limited number of resistance studies were calculated separately for these genders. In most studies, age category is one of the affecting factors on mentioned resistance rate; however, due to nonentity in mentioning of the age group in a large number of studies and also due to the lack of entity similar age groups in the number of other studies, we could not calculate the resistance rate in terms of age; another limitation of this study was the lack of determined resistance rate by type of patient admission because such information did not exist in large number of compiled studies.

Conclusions

According to the present study, E. coli was the most common cause of UTI, and after that, Klebsiella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterobacter rank the next category. The results of this study showed that resistance is likely to be against the most common used antibiotics. The most effective antibiotics for E. coli are imipenem, nitrofurantoin, amikacin, chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin. By considering the results of this study, less use of gentamicin, the second generation of cephalosporins and nalidixic acid recommended, on the other hand, consuming of the penicillin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and the first generation of cephalosporins prescribed in the initial treatment of infections caused by E. coli. For Klebsiella isolates that separate from urine samples, effective antibiotics are imipenem, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, and nalidixic acid. Similarly, the use of ampicillin and cephalexin is not recommended in this case. In the treatment of UTIs that caused by Staphylococcus, ciprofloxacin is prescribed and consumed. It is obvious that due to the more use of antibiotics, uncontrolled use, and antibiotics misuse, antibiotic resistance emerging control is essential and this is one of the most important factors affecting these phenomena and attempts should be made for proper use of antibiotics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cybulski Z, Schmidt K, Grabiec A, Talaga Z, Bociąg P, Wojciechowicz J, et al. Usability application of multiplex polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of microorganisms isolated from urine of patients treated in cancer hospital. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:296–303. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalilian S, Farahani A, Mohajeri P. Antibiotic resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infections out-patients in Kermanshah. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health. 2014;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isvand A, Yahyavi M, Asadi-Samani M, Kooti W, Davoodi-Jouneghani Z. The study of bacteriological factors and antibiotic resistance in women with UTI referred to the Razi laboratory in Dezful. Sci J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2014;22:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharifi A, Khoramrooz S, Khosravani S, Yazdanpanah M, Gharibpour F, Malekhoseini A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Escherichia coli isolated from patients with urinary tract infection (UTI) in Yasuj city during 1391-1392. J Armaghane Danesh Yasuj Univ Med Sci. 2014;19:337–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asadi Manesh FF, Sharifi A, Mohammad Hosini Z, Nasrolahi H, Hosseini N, Kalantari A, et al. Antibiotic resistance of urinary tract infection of children under 14 years admitted to the pediatric clinic of Imam Sajjad hospital, 2012. Armaghane Danesh. 2014;19:411–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copp HL, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL. National ambulatory antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric urinary tract infection, 1998-2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1027–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molazade A, Shahi A, Gholami M, Najafipour S, Jafari S, Mobasheri F, et al. The antibiotic resistance pattern of gram-negative Bacilli isolated from urine cultures of adult outpatients admitted to Vali Asr Hospital of Fasa Clinical Laboratory in 2012-13. J Jahrom Univ Med Sci. 2014;12:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moghadas A, Irajian G. Asymptomatic urinary tract infection in pregnant women. Iran J Pathol. 2009;4:105–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS. Study Guide for Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology-E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee G, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, et al. K: A Pathophysiologic Approach: Appleton and Lange. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Farmer P, Mark DB, Martin GJ, Roden DM, Dunaif AE, et al. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. Women's Health. 2008;39:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: No ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1–2. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griebling TL. Urinary tract infection in women. Urologic diseases in America. 2007;7:587–619. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linhares I, Raposo T, Rodrigues A, Almeida A. Frequency and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria implicated in community urinary tract infections: A ten-year surveillance study (2000-2009) BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Morúa A, Hernández-Torres A, Salazar-de-Hoyos J, Jaime-Dávila R, Gómez-Guerra L. Community-acquired urinary tract infection etiology and antibiotic resistance in a Mexican population group. Rev Mex Urol. 2009;69:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oladeinde BH, Omoregie R, Olley M, Anunibe JA. Urinary tract infection in a rural community of Nigeria. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:75–7. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dibua UM, Onyemerela IS, Nweze EI. Frequency, urinalysis and susceptibility profile of pathogens causing urinary tract infections in Enugu State, Southeast Nigeria. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56:55–9. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LF, Chiu CT, Lo JY, Tsai SY, Weng LS, Anderson DJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of hospitalized patients with community acquired urinary tract infections at a regional hospital in Taiwan. Healthc Infect. 2013;19:20–5. doi: 10.1071/HI13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George CE, Norman G, Ramana GV, Mukherjee D, Rao T. Treatment of uncomplicated symptomatic urinary tract infections: Resistance patterns and misuse of antibiotics. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:416–21. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.161342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalsoom B, Jafar K, Begum H, Munir S, ul Akbar N, Ansari JA, et al. Patterns of antibiotic sensitivity of bacterial pathogens among urinary tract infections (UTI) patients in a Pakistani population. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2012;6:414–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kothari A, Sagar V. Antibiotic resistance in pathogens causing community-acquired urinary tract infections in India: A multicenter study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:354–8. doi: 10.3855/jidc.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen R, Gillet Y, Faye A. Synthesis of management of urinary tract infections in children. Arch Pediatr. 2012;19(Suppl 3):S124–8. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(12)71285-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kader AA, Kumar A, Dass SM. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of gram-negative bacteria isolated from urine cultures at a general hospital. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2004;15:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yolbaş I, Tekin R, Kelekci S, Tekin A, Okur MH, Ece A, et al. Community-acquired urinary tract infections in children: Pathogens, antibiotic susceptibility and seasonal changes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:971–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DS, Choe HS, Lee SJ, Bae WJ, Cho HJ, Yoon BI, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and epidemiology of female urinary tract infections in South Korea, 2010-2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5384–93. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majumder MI, Ahmed T, Hossain D, Begum SA. Bacteriology and antibiotic sensitivity patterns of urinary tract infections in a tertiary hospital in Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2014;23:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abejew AA, Denboba AA, Mekonnen AG. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern of urinary tract bacterial infections in Dessie area, North-East Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:687. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stratchounski LS, Rafalski VV. Antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens isolated from adult patients with uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infections in the Russian Federation: Two multicentre studies, UTIAP-1 and UTIAP-2. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28(Suppl 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickerson AD, Carson CC. The treatment of urinary tract infections and use of ciprofloxacin extended release. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:519–32. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo DS, Shieh HH, Ragazzi SL, Koch VH, Martinez MB, Gilio AE, et al. Community-acquired urinary tract infection: Age and gender-dependent etiology. J Bras Nefrol. 2013;35:93–8. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20130016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamenski G, Wagner G, Zehetmayer S, Fink W, Spiegel W, Hoffmann K, et al. Antibacterial resistances in uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women: ECO·SENS II data from primary health care in Austria. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renuart AJ, Goldfarb DM, Mokomane M, Tawanana EO, Narasimhamurthy M, Steenhoff AP, et al. Microbiology of urinary tract infections in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukherjee M, Basu S, Mukherjee SK, Majumder M. Multidrug-resistance and extended spectrum beta-lactamase production in uropathogenic E. coli which were isolated from hospitalized patients in Kolkata, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:449–53. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4990.2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouza E, San Juan R, Muñoz P, Voss A, Kluytmans J. Co-operative Group of the European Study Group on Nosocomial Infections. A European perspective on nosocomial urinary tract infections I. Report on the microbiology workload, etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility (ESGNI-003 study). European study group on nosocomial infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:523–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldstein FW. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial strains isolated from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infections in France. Multicentre study group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:112–7. doi: 10.1007/s100960050440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharmin S, Alamgir F, Fahmida M, Saleh AA. Antimicrobial sensitivity pattern of uropathogens in children. Bangladesh J Med Microbiol. 2010;3:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abejew AA, Denboba AA, Mekonnen AG. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern of urinary tract bacterial infections in Dessie area, North-East Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narchi H, Al-Hamdan MA. Antibiotic resistance trends in paediatric community-acquired first urinary tract infections in the United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guidoni EB, Berezin EN, Nigro S, Santiago NA, Benini V, Toporovski J, et al. Antibiotic resistance patterns of pediatric community-acquired urinary infections. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:321–3. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702008000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolff O, Maclennan C. Evidence behind the WHO guidelines: Hospital care for children: What is the appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated urinary tract infections in children in developing countries? J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:150–2. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantadakis E, Tsalkidis A, Panopoulou M, Pagkalis S, Tripsianis G, Falagas ME, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of pediatric uropathogens in Thrace, Greece. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:549–55. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhanel GG, Hisanaga TL, Laing NM, DeCorby MR, Nichol KA, Weshnoweski B, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli outpatient urinary isolates: Final results from the North American Urinary Tract Infection Collaborative Alliance (NAUTICA) Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:468–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karlowsky JA, Lagacé-Wiens PR, Simner PJ, DeCorby MR, Adam HJ, Walkty A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in urinary tract pathogens in Canada from 2007 to 2009: CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3169–75. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00066-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daoud Z, Afif C. Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infections of Lebanese patients between 2000 and 2009: Epidemiology and profiles of resistance. Chemother Res Pract. 2011;2011:218431. doi: 10.1155/2011/218431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sire JM, Nabeth P, Perrier-Gros-Claude JD, Bahsoun I, Siby T, Macondo EA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in outpatient Escherichia coli urinary isolates in Dakar, Senegal. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2007;1:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishna S, Pushpalatha H, Srihari N, Nagabhushan S, Divya P. Increasing resistance patterns of pathogenic bacteria causing urinary tract infections at a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pharm Biomed Res. 2013;4:105–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aypak C, Altunsoy A, Düzgün N. Empiric antibiotic therapy in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections and fluoroquinolone resistance: A prospective observational study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2009;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez-Avial C, Rodríguez-Avial I, Hernández E, Picazo JJ. Increasing prevalence of fosfomycin resistance in extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli urinary isolates (2005-2009-2011) Rev Esp Quimioter. 2013;26:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Donk CF, van de Bovenkamp JH, De Brauwer EI, De Mol P, Feldhoff KH, Kalka-Moll WM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and spread of multi drug resistant Escherichia coli isolates collected from nine urology services in the Euregion Meuse-Rhine. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magliano E, Grazioli V, Deflorio L, Leuci AI, Mattina R, Romano P, et al. Gender and age-dependent etiology of community-acquired urinary tract infections. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:349597. doi: 10.1100/2012/349597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barisić Z, Babić-Erceg A, Borzić E, Zoranić V, Kaliterna V, Carev M, et al. Urinary tract infections in South Croatia: Aetiology and antimicrobial resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22(Suppl 2):61–4. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muhammad I, Uzma M, Yasmin B, Mehmood Q, Habib B. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and integrons in Escherichia coli from Punjab, Pakistan. Braz J Microbiol. 2011;42:462–6. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822011000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mbata T. Prevalenceand antibiogram of urinary tract infection among prison inmates in Nigeria. Internet J Microbiol. 2007;3:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nerurkar A, Solanky P, Naik S. Bacterial pathogens in urinary tract infection and antibiotic susceptibility pattern. J Pharm Biomed Sci. 2012;21:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gales AC, Sader HS, Jones RN SENTRY Participants Group (Latin America) Urinary tract infection trends in Latin American hospitals: Report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (1997-2000) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;44:289–99. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arredondo-García JL, Soriano-Becerril D, Solórzano-Santos F, Arbo-Sosa A, Coria-Jiménez R, Arzate-Barbosa P, et al. Resistance of uropathogenic bacteria to first-line antibiotics in Mexico city: A multicenter susceptibility analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2007;68:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pape L, Gunzer F, Ziesing S, Pape A, Offner G, Ehrich JH, et al. Bacterial pathogens, resistance patterns and treatment options in community acquired pediatric urinary tract infection. Klin Padiatr. 2004;216:83–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshikawa TT, Nicolle LE, Norman DC. Management of complicated urinary tract infection in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1235–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talan DA, Naber KG, Palou J, Elkharrat D. Extended-release ciprofloxacin (Cipro XR) for treatment of urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-Zahrani AJ, Akhtar N. Susceptibility patterns of extended spectrum ß-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in a teaching hospital. Pak J Med Res. 2005;44:64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao Y, Hu Y. The major aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme AAC(3)-II found in Escherichia coli determines a significant disparity in its resistance to gentamicin and amikacin in China. Microb Drug Resist. 2012;18:42–6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2010.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ti TY, Kumarasinghe G, Taylor MB, Tan SL, Ee A, Chua C, et al. What is true community-acquired urinary tract infection? Comparison of pathogens identified in urine from routine outpatient specimens and from community clinics in a prospective study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:242–5. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance Surveillance in Europe, 2009. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tarhani F, Kazemi AH, Abedini MR, Rashidi R. Antibiotic resistance in urinary tract infections in children hospitalized in Shahid Madani hospital Khorramabad during 2001-2002. Q Res J Lorestan Univ Med Sci. 2003;5:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Momeni Mofrad S, Goudarzi G, Shakib P, Nowroozi J. Prevalence of aac (3)-IIa gene among clinical isolates of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Delfan, Lorestan. Iran J Med Microbiol. 2013;7:20–6. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lutter SA, Currie ML, Mitz LB, Greenbaum LA. Antibiotic resistance patterns in children hospitalized for urinary tract infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:924–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.10.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nováková I, Kačániová M, Haščík P, Pavličová S, Hleba L. The resistance to antibiotics in strains of E. coli and Enterococcus sp. isolated from rectal swabs of lambs and calves. Sci Pap Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2009;42:322–6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qiao LD, Chen S, Yang Y, Zhang K, Zheng B, Guo HF, et al. Characteristics of urinary tract infection pathogens and theirin vitro susceptibility to antimicrobial agents in China: Data from a multicenter study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e004152. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Tawfiq JA. Increasing antibiotic resistance among isolates of Escherichia coli recovered from inpatients and outpatients in a Saudi Arabian hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:748–53. doi: 10.1086/505336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nickavar A, Sotoudeh K. Treatment and prophylaxis in pediatric urinary tract infection. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:4–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beyene G, Tsegaye W. Bacterial uropathogens in urinary tract infection and antibiotic susceptibility pattern in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21:141–6. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v21i2.69055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jarsiah P, Alizadeh A, Mehdizadeh E, Ataee R, Khanalipour N, Student P, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance model of Escherichia coli in urine culture samples at Kian hospital lab in Tehran. J Mazand Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chakupurakal R, Ahmed M, Sobithadevi DN, Chinnappan S, Reynolds T. Urinary tract pathogens and resistance pattern. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:652–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.074617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Molazadeh M, Mola Abbas Zadeh H, Mohammad Zadeh N. The pattern of sensitivity and resistance antibiotics in E. coli strains isolated from urine samples of pregnant women in Khoy and Salmas in West Azerbaijan province. Sci J Micro Biotech Islamic Azad Univ. 2012;4:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mohajeri P, Izadi B, Naghshi N. Evaluation of antibiotic sensitivity of E. coli isolated from urinary infections patients referred to Kermanshah Central Laboratory in 2008. Bimonthly J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2011;15:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mosavian SM, Mashali K. Study of bacterial urinary tract infection after catheterization and determine antibiotic resistance of bacteria isolated from patients. Sci J Hamedan Univ Med Sci. 2004;11:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Madani SH, Khazaee S, Kanani M, Shahi M. Antibiotic resistance pattern of E. coli isolated from urine culture in Imam Reza Hospital Kermanshah-2006. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2008;12:287–95. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sorkhi H, Jabbarian Amiri A, Askarian A. Escherichia coli and drug sensitivity in children with urinary tract infection. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2005;14:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ghoutaslou R, Abdoli OS, Mesri A. The in vitro activity of ciprofloxacin on isolated organisms from urinary tract infections in a pediatric hospital. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nourozi J, Mirjalili A, Azhdari A. Urinary infection in residents of Kahrizak Charity Foundation in Tehran during 1998. Feyz. 2000;13:104–9. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alaie V, Saleh Zadeh F. Clinical protests and antibiogram results in 510 children with urinary tract infection. J Ardebil Univ Med Sci. 2008;8:274–80. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torabi S, Falak-ul-Aflaki B, Moezzi F. In vitro Antimicrobial drug-resistance of urinary tract pathogens in patients admitted to Vali-e-Asr hospital wards. Zanjan Univ Med Sci J. 2007;15:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hajizade N, Kh D. Evaluation ofin vitro antimicrobial drug-resistance in Imam Khomini hospital. Iran J Pediatr. 2003;13:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eghbalian F, Usefi MR. Determining the frequency of the bacterial agents in urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients under 18 years old in Ekbatan hospital. J Army Univ Med Sci. 2005;3:635–70. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mirmostafa M, Hadadi A, Mozafari Sabet N. Plasmid profiles and antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli isolated from patients in different parts of the city of Karaj. NCMBJ. 2013;3:93–7. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mobasheri A, Tabaraie A, Ghaemi A, Mojerlou M, Vakili M, Dastforoshan M, et al. The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women admitted to hospital Dezyani-Gorgan. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2002;4:42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Asgharian A. Investigation of antibiotic susceptibility pattern of E. coli isolated from urinary culture related to patients in the west of the Mazandaran province, during from September 2010 to September 2011. Sci J Exp Anim Biol. 2011;1:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharif A, Adib M, Mousavi G, Sharif M, Ghavoshi G. The antibiotic resistance in bacterial agents of urinary tract infections in Kashan during 1995-1997. Feyz. 1999;9:41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rahimi MK, Falsafi S, Tayebi Z, Msoumi M, Ferasat PMR, Mirzaie A. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of human pathogenic bacteria isolated from patients with urinary tract infection. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mokhtarian H, Ghahramani M, Nourzad H. A study of antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infection. Q J Horiz Med Sci. 2006;12:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Assefzadeh M, Hagmanochehri F, Mohammadi N, Tavakoli N. Prevalence of pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in urine cultures of patients referred to Avesina medical center in Qazvin. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2009;13:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hamid-Farahani R, Tajik A, Noorifard M, Keshavarz A, Taghipour N, Hosseini S. Antibiotic resistance pattern of E. coli isolated from urine culture in 660 Army clinical laboratory center in Tehran 2008. J Army Univ Med Sci. 2012;10:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mohammadi M. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections. Med Sci J Azad Univ. 2006;16:95–9. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fahimi D, Rahbari Manesh A, Seifolahi A, Rezaei N. The survey of microorganisms causing urinary tract infections and their susceptibility to antibiotics in children referred to Bahrami Pediatrics Hospital, during 1996-2003. J Army Univ Med Sci. 2003;1:223–7. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saedi S, Chakerzehi A, Soltani N, Honarmand M, Yazdanpanah M, Ghazvini K, et al. Nosocomial urinary tract infections: Etiology, risk factors and antimicrobial pattern in Ghaem university hospital in Mashhad. J Paramed Sci Rehabil. 2013;2:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yazdi M, Nazemi A, Mir IM, Khataminejad M, Sharifi S, Babai Kochkasaraei M. The prevalence of beta-lactamase resistance genes SHV CTX-M TEM in E. coli isolated from urinary tract infection in Tehran. Med Lab J. 2010;4:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yadollahi H. Study of bacterial and antibiogram causes urinary tract infections in children of Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari province in 1992-1997. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2002;4:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Soleimani NA, Amini Z, Tajbakhsh E. The study of attachment factor and biofilm formation of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from patient with urinary tract infection of Semnan Province. Pajoohandeh J. 2014;18:332–6. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moulana Z, Asgharpour F, Ramezani T. Frequency of the bacterial causing agents in urinary tract infection and antibiotic pattern samples sent to Razi laboratory, Babol 2008-2009: A short report. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2013;12:489–94. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Heidari-Soureshjani E, Heidari M, Doosti A. Epidemiology of urinary tract infection and antibiotic resistance pattern of E. coli in patients referred to Imam Ali hospital in Farokhshahr, Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari, Iran. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;15:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Soltan Dallal M, Sharifi Yazdi M. Comparison of multiple antibiotic resistance patterns of Klebsiella bacteria groups causing urinary infections and determination of imipenem MIC in MDR strains. ZUMS J. 2014;22:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yazdi MK, Dallal MM. Prevalence study of Enterococus and staphylococci resistance to vancomycin isolated from urinary tract infections. Tehran Univ Med Sci. 2013;71:250–8. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fesharakinia A, Malekaneh M, Hooshyar H, Aval M, Gandomy-Sany F. The survey of bacterial etiology and their resistance to antibiotics of urinary tract infections in children of Birjand city. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2012;19:208–15. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jalalpoor S, Mobasherizadeh S. Frequency of ESBLs in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from hospitalized and out-patients with urinary tract infection in selective centers in Esfahan (2009-2010) Razi J Med Sci. 2011;18:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mohammadimehr M, Feizabadi M, Bahadori A. Antibiotic resistance pattern of Gram negative Bacilli Caused nosocomial infections in ICUs in Khanevadeh and Golestan hospital in Tehran-2007. Ann Mil Health Sci Res. 2011;8:283–90. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sahebnagh R, Saderi H, Boroumandi S. Comparison of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from urine of adult patients with regard to gender, age and kind of admission. Daneshvar Med J. 2015;114:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Safkhani E, Saderi H, Boroumandi S, Faghihzadeh E, Akhavi Rad S, Moosavi SM. Bacteria isolated from urine of children with different sex and ages. Daneshvar Med J. 2014;113:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Asghari Moghadam N, Rasoulzade R, Hosseini Moghadam SM, Seifi M, Pourshafie MR, Talebi M. Isolation and identification of antibiotic resistance and study of genotyping of P. aeruginosa causing urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients in Shohada and Labbafinejad Tehran hospitals. J Isfahan Univ Med Sci. 2014;32:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mortezavi R, Khosravani S, Naghavi N. Molecular analysis of gene frequencies of TEM, CTX-M and SHV in beta-lactam antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli isolated from urinary tract infections in Yasuj hospitals. Armaghane Danesh. 2014;19:233–41. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dehbashi S, Pourmand M, Mahmoudi M, Mashhadi R. Molecular identification of Streptococcus agalactiae using gbs1805 gene and determination of the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of isolates. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2015;17:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Savadkoohi R, Sorkhi H, Poyrnasrollah M, Khalilian E, Mahdi Pour E. Antibiotics resistance of bacteria causing urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients in University hospital Amirkola – Babol between 84-1381. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2007;12:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sharif M, Nouri S. The prevalence and pattern of antibiotic resistance organisms causing urinary tract infections in children. Shahid Beheshti Kashan hospital, 2012-2013. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2014;19:51–75. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Esmaeili R, Hashemi H, Moghadam Shakib M, Alikhani M. Bacterial etiology of urinary tract infections and determining their antibiotic resistance in adults hospitalized in or referred to the Farshchian hospital in Hamadan. Sci J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2013;21:281–7. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hosseini M, Farhangara E, Yousefi Masheof R, Parsavash P. Prevalence and determining of antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from urine culture of patients hospitalized (Qazvin) Med Lab J. 2014;8:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shahraki S, Bokaiean M, Rigi S. Antibiotic resistance pattern and prevalence of ESBLs in Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary isolates. Med Lab J. 2014;8:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bagheri H, Najafi F, Behnampour N, Ghaemi E. Frequency of multi-drug resistance (MDR) in Gram negative bacteria from urinary infection in Gorgan, 2011-12. Med Lab J. 2015;8:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Molazade A, Shahi A, Najafipour S, Mobasheri F, Norouzi F, Abdollahi Kheirabadi S, et al. Antibiotic resistance pattern of bacteria causing urinary tract infections in children of Fasa during the years 2012 and 2014. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2015;4:493–9. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Molazade A, Gholami M, Shahi A, Najafipour S, Mobasheri F, Ashraf Mansuri J, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance pattern of isolated gram-negative bacteria from urine culture of hospitalized patients in different wards of Vali-Asr Hospital in Fasa during the years 2012 and 2013. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2014;4:275–83. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Molaabaszadeh H, Hajisheikhzadeh B, Mollazadeh M, Eslami K, Mohammadzadeh Gheshlaghi N. Study of sensibility and antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infection in Tabriz city. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2013;3:149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Farajnia S, Alikhani MY, Ghotaslou R, Naghili B, Nakhlband A. Causative agents and antimicrobial susceptibilities of urinary tract infections in the Northwest of Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ahangarkani F, Rajabnia R, Shahandashti EF, Bagheri M, Ramez M. Frequency of class 1 integron in Escherichia coli strains isolated from patients with urinary tract infections in North of Iran. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27:10–2. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.27.10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nasiri MZ. Survey on the sensitivity of E. coli to amoxicillin and co-trimoxazole in urinary infections. Asrar J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2000;7:38–42. [Google Scholar]