Abstract

Background:

Health literacy is an issue that is influenced by social determinants and improved by community-based initiatives. Enhancing health literacy can lead to patient engagement, appropriate use of health care, and improved health outcomes. Understanding the community stories by working with vulnerable populations, such as English language learners (ELL), can help inform other health literacy projects on how to enable ELL immigrants to be involved in their health care.

Brief Description of Activity:

“Health in the English Language” was an 8-week course based on the social view of health literacy that was created and taught by university students. This curriculum was implemented at the Alaska Literacy Program (ALP) during the summer of 2018 in Anchorage, Alaska. Course participants were adult ELL.

Implementation:

Throughout the summer, the course curriculum was adapted to fit students' needs. Course participants completed open-ended evaluations during the class, and feedback was obtained via interviews with leaders in the community and leaders at ALP. Community organizations were brought into the classroom using resource sheets and an end-of-course community health fair.

Results:

Student evaluations identified important themes of managing health care and medications, as well as learning new words. Feedback from ALP and community partners highlighted active teaching styles and how the course benefited the community. The results reflect the impact the course had on increasing student confidence, knowledge, and skills to interact with health care providers. The course created a culture that facilitated the ability of immigrant community members to access health resources. The feedback received demonstrated the importance of university students partnering with nonprofits to create effective health literacy programs that are community centered.

Lessons learned:

Similar programs can be replicated using community and university partnerships to address health literacy problems. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2019;3(Suppl.):S79–S87.]

Plain Language Summary:

The course “Health in the English Language” was created to teach English and skills to understand health information to English language learners. The course leaders worked with community-based organizations. A variety of content, such as going to the doctor's office, reading medication labels, describing symptoms, and staying healthy, was included.

Health literacy is essential for personal and community empowerment to overcome barriers to health (Nutbeam, 2000). Community partnerships and social interactions can enhance health literacy for English language learners (ELL) when integrated into adult literacy education programs (Santos, Handley, Omark, & Schillinger, 2014). The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2008) defines health literacy as “the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions.” People lacking listening, numeracy, and reading skills to engage actively in their health care have worse health outcomes (Squiers, Peinado, Berkman, Boudewyns, & McCormack, 2012). Approximately 80 million Americans have limited health literacy, correlating with greater numbers of hospitalizations and use of emergency care, and lower rates of medication adherence and vaccinations (Berkman, Sheridan, Donahue, Halpern, & Crotty, 2011). Health literacy is also highly dependent on socioeconomic and education levels (Feinberg et al., 2016). Disparities in social status can exacerbate obstacles to health care, such as limited access to care and financial resources (Freedman et al., 2009). Positive health behaviors therefore are limited by social factors. Improving health literacy can enhance self-management abilities, increase use of preventive services, and address health inequalities (Stevens, 2015).

Health Literacy in ELL Populations

Low health literacy often is associated with age, education, and ethnicity (Logan et al., 2015). However, health literacy interventions fail to consider the poor health outcomes immigrants and adult ELL face due to communication barriers and low health literacy (Tsoh et al., 2016). Given the importance of health education initiatives in health promotion, health literacy lessons for immigrant populations require culturally appropriate programming and materials (Fernández-Gutiérrez, Bas-Sarmiento, Albar-Marin, Paloma-Castro, & Romero-Sanchez, 2018). Some strategies attempt to focus on groups that are actually diverse but are linguistically or ethnically homogenous, such as Spanish speakers in the United States and Chinese immigrants in Canada. These programs aim to bypass the language barrier and communicate information effectively by using bilingual teachers (Mas, Mein, Fuentes, Thatcher, & Balcázar, 2013) and materials formatted for a singular cultural context or health topic (Taylor et al., 2008; Tsoh et al., 2016).

Fernández-Gutiérrez et al. (2018) recommend that health literacy programming, especially educational modules for immigrant populations, incorporate input from partner organizations for culturally competent community health practices. Knowledge of students' social practices can help tailor a health literacy curriculum to the social environment. Use of community support has been found to improve health knowledge in populations, particularly older adults (De Wit et al., 2017). Health literacy interventions that are culturally appropriate tend to improve the health status and comprehension levels of ELL students (Tsoh et al., 2016).

Social View of Health Literacy

ELL settings can address health disparities in under-served immigrant populations such as those with limited schooling and literacy, as well as those who are elderly or lack legal documentation (Santos et al., 2014). This can be accomplished using either the social or functional views of health literacy. The functional view emphasizes the set of reading and writing skills one uses to improve health outcomes (Heijmans, Waverijn, Rademakers, van der Vaart, & Rijken, 2015). The social view, on the other hand, expands on this by equipping students to participate in a complex health care system while learning about opportunities to improve their health (Santos et al., 2014).

The social view of health literacy could be applied by creating community partnerships and classroom activities that are relevant to meeting students' health needs (Estacio, 2013). Social skills are known to affect the ways in which people are able to gather and understand information through communication in everyday life interactions (Sørensen et al., 2012). Thus, the sociocultural approach to literacy and communication helps students navigate the health care system by teaching students about health components using actual materials such as prescriptions, registration forms, and online information (Mas et al., 2013).

Moreover, health education efforts can motivate target populations to solve health problems and empower communities through consistent feedback and resources that build community relationships (McCormack, Thomas, Lewis, & Rudd, 2017). Understanding the social context, and therefore the culture in which students live, can assist in developing a health literacy intervention that is appropriate for populations facing low health literacy. Collaborations between education and health care have been encouraged to empower ELL students to work with their communities to be healthy (Taylor et al., 2008). This article describes a university student partnership with the Alaska Literacy Project (ALP) and the Anchorage, Alaska, community in the summer of 2018 to examine the experiences of ELL students at ALP and stake-holders involved in a course entitled “Health in the English Language.”

Description of Activity

Two university undergraduate students (J.S. and A.S) designed a health literacy course as a new offering for the summer of 2018. The course was available to students at ALP, a nonprofit organization in Anchorage, Alaska committed to “changing lives through literacy.” The organization's work consists of recruiting, training, and supporting volunteer instructors from the community to teach language skills to adult learners. ALP provides classes in a variety of literacy levels and topics, such as Career Pathway and Voices of Freedom, to offer students opportunities to be independent and engaged community members. The university student partnership with ALP began in October 2017 and was fostered through frequent online meetings between the university students and ALP staff during a 7-month period. The partnership was solidified when the two university students spent 8 weeks in Anchorage, Alaska leading the Health in the English Language class in the summer of 2018.

The student body at ALP included men and women of different ethnicities (Table 1). The majority of ALP students were of Hispanic/Latino (47.4%) or Asian descent (27.4%), women (79.4%), and ages 25 to 59 years (81.7%). Literacy levels of students were evaluated by ALP using the Test for Adult Basic Education (TABE), and oral English proficiency and literacy proficiency were evaluated using Basic English Skills Test (BEST) Plus and BEST Literacy, respectively (Table 2). When students tested out of both BEST Plus and BEST Literacy, they then completed the TABE for an additional assessment (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2019a; Center for Applied Linguistics, 2019b; Data Recognition Corporation, 2018). Students were enrolled in classes based on their literacy level, schedule, and personal goals. Literacy levels for the ALP summer 2018 participants were classified as English as a Second Language (ESL) low beginning (34.9%), ESL beginning literacy (22.3%), and ESL high beginning (13.7%); and ESL intermediate low (6.3%), ESL intermediate high (8%), and ESL advanced (0.5%). The remaining ALP students (14.3%) were classified as non-ESL, because they were assigned TABE literacy levels. The literacy levels for the majority of students at ALP were ESL low beginning, ESL beginning literacy, and ESL high beginning.

Table 1.

Alaska Literacy Project Students' Ethnicity and Gender by Age Groups for Summer 2018

| Age Group, years | Ethnicity | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska Native | Asian | Black/African-American | Hispanic/Latino | Pacific Islander | White | ||||||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | ||

| 16–18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 19–24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 25–44 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 31 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 78 |

| 45–59 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 65 |

| ≥60 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Total | 0 | 1 | 4 | 44 | 9 | 14 | 18 | 65 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 175 |

Note. F = female; M = male. Data courtesy of Alaska Literacy Program; used with permission.

Table 2.

Alaska Literacy Project Students' Test for Adult Basic Education, BEST Plus, and BEST Literacy Test Measures by Ethnicity and Gender for Summer 2018

| Functioning Level | Ethnicity | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Alaska Native | Asian | Black/African-American | Hispanic/Latino | Pacific Islander | White | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| ABE beginning literacy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ABE beginning basic | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ABE intermediate low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ABE intermediate high | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| ASE low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| ASE high | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL beginning literacy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 39 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL low beginning | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 61 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL high beginning | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 24 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL intermediate low | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL intermediate high | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| ESL advanced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Total | 0 | 1 | 4 | 44 | 9 | 14 | 18 | 65 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 175 |

Note. The Alaska Literacy Program assesses its students annually with either the Test for Adult Basic Education (TABE) or the Basic English Skills Test (BEST) Plus and BEST literacy examinations. TABE results yield Adult Basic Education (ABE) functioning levels, whereas BEST Plus and BEST Literacy show Adult Secondary Education (ASE) and English as a Second Language (ESL) functioning levels. F = female; M = male. Data courtesy of Alaska Literacy Program; used with permission.

The Health in the English Language course was offered as an intermediate literacy course at ALP to foster health literacy and cultivate a community network to enhance well-being. A total of 25 students registered for the course and were present intermittently throughout the duration of the course; an average of 14 students were present at each session during the scheduled class times. Five ALP students joined the course after registration. The class was held twice a week with 90-minute sessions for 8 weeks. A typical lesson used handouts with key health-related vocabulary, resources from relevant local services (e.g., contact information of local clinics and urgent cares), and interactive, hands-on group activities.

Lesson plans, class worksheets, and materials were created by two of the authors (J.S. and A.S.) during the 2017–2018 school year. Both students were motivated to address health literacy after learning, through coursework, about the challenges and consequences faced by immigrants with low health literacy. The university students, or course leaders, shared a passion for community interventions and designed the Health in the English Language course to improve health literacy. They initiated the project out of their own interests and did not receive course credit. University faculty assisted the students in securing funding, refining the idea, and identifying a community partner organization. Student-specific grant opportunities from the Georgetown University Social Impact and Public Service Fund, Georgetown University International Relations Association, Georgetown University Research Opportunities Program, and Theta Foundation provided the students with funding for the project. ALP provided the undergraduate students with ELL teaching training materials and advised the students on effective teaching strategies throughout the creation of the curriculum.

The course leaders (J.S. and A.S.) used input from community members, including ALP leadership, volunteers, and colleagues at partner organizations, to design the lesson plans and interactive class activities. The course leaders also identified local services in Anchorage that promote healthy behaviors, such as the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) working to prevent diabetes, to determine available community resources aimed at improving health literacy. Engaging with community partners enacted the social view of health literacy by integrating relevant partners and community resources within curricular content.

Implementation

Curriculum Development

Development of The Health in the English Language curriculum began with exploring the Healthy Alaskans 2020 Scorecard (Alaska Department of Health and Social Services and Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, 2017) and Health Literacy: Guidance and Tools (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). These sources identified leading health problems and served as the initial platform to build curriculum topics. Further exploration indicated these topics alone were not enough to support the attainment of general and transferable abilities to provide usability across the lives of course participants to support health and well-being for themselves and their families. Active learning with interactive opportunities and helping people identify strategies that will work for them in health care situations was more helpful than cognitive domain learning (Papen, 2008).

Initial classes addressed using and understanding the health care system, including scheduling appointments, going to the doctor, explaining symptoms, and taking medications, to provide common language and gain comfort with the teachers and classmates. Subsequent classes discussed nutrition, physical activity, mental health, first aid, oral health, vaccinations, and health insurance. Using community resources and engaging with social networks on many of these areas aimed to strengthen health literacy (Papen, 2008).

To integrate the social view of health literacy and adapt the curriculum to suit the ALP students, community feedback was solicited through meetings with community health leaders, such as Providence Hospital staff and Peer Leader Navigators (PLNs). PLNs are students who graduated from ALP and assist other students with adjusting to life in Alaska. The PLNs helped course leaders create relevant, helpful class materials. Course leaders also reached out to community organizations that address health and wellness in Anchorage; these included recreational programs, social groups, grocery stores, farmers' markets, clinics, pharmacies, and municipal services. Each organization was identified to have a mission that aligned with improving the health of Anchorage residents. Eight community organizations participated in the end-of-term health fair, with others offering additional giveaways and food for the event. The use of multiple health resources aimed to connect class concepts to real-world applications.

Lesson Structure

Each lesson included a 15-minute warm-up and review, a 60-minute main activity, and a 15-minute closing and reflection. Class warm-up involved highlighting vocabulary and information students should recall from prior classes. Students used definitions and said the word out loud to practice pronunciation. The main activity was dedicated to new concepts and words, and often incorporated station and partner work for application. Navigating various literacy levels required teachers to provide creative resources for the students in the form of visuals, movements, and objects; for example, lessons included individual and small group station activity with questions about actual over-the-counter and prescription medications rather than passive learning with printed labels. Students were encouraged to work with one another and reach out to the teacher if they were struggling. Class concluded with open-ended feedback evaluations, and students were asked to record their responses about how they felt about certain topics or tell the course leaders some of the ideas they learned during the class, using Teach-Back techniques.

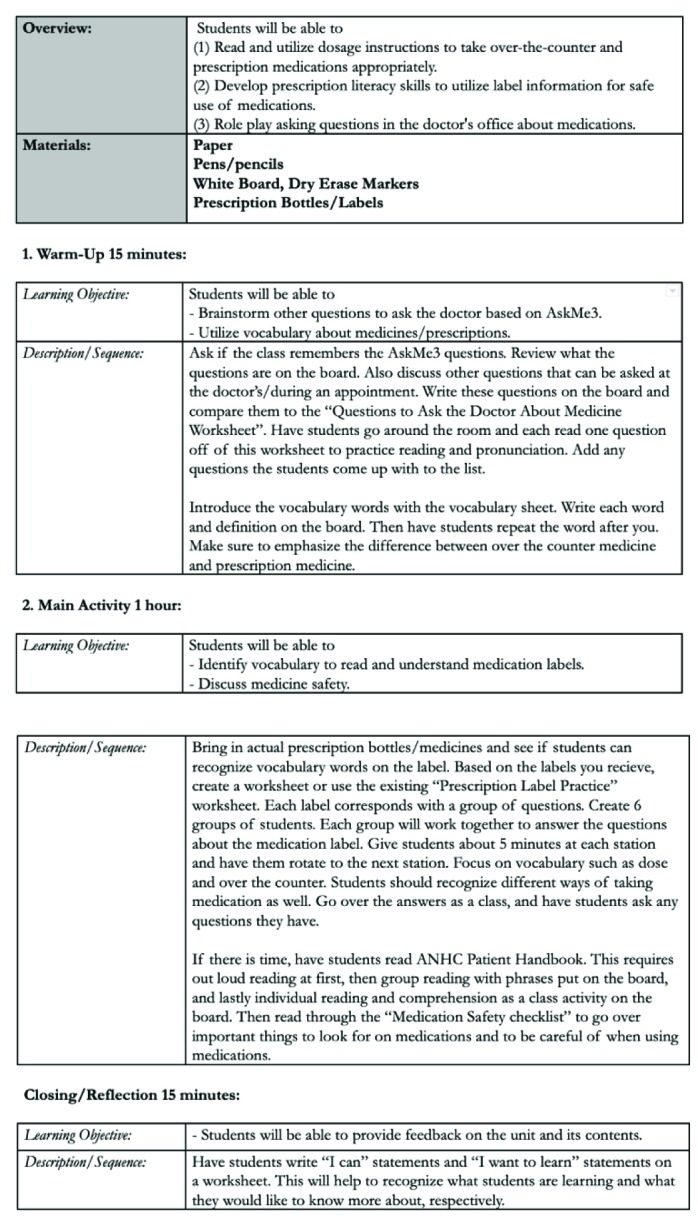

Figure 1 shows a lesson plan for day 4 of the class. The class began with brainstorming questions that could be asked at an appointment to clarify medical information with new vocabulary surrounding over-the-counter and prescription medicines (warm-up). Students then completed a station activity in which they had to answer questions about the medicine displayed in different parts of the classroom (main activity). The class concluded with students responding on a worksheet to prompts about their learning (closing and reflection).

Figure 1.

Example of a lesson plan from the Health in the English Language course at Alaska Literacy Program.

Evaluation Methods

Evaluation worksheets were given to students to provide feedback throughout the course. Participants also were asked to provide open-ended feedback for formative assessment to help facilitators adjust their teaching plan, review content, or address student questions every 2 weeks. The formative evaluation worksheets asked students to complete phrases such as “I can . . .” and “I want to learn more about . . .” Mid-course evaluation involved individual responses to a “3-2-1” activity in which students listed three things they just learned, two things they considered interesting, and one question they still had about course content. Final course feedback asked students to indicate the most meaningful topic for them.

Student responses from the evaluations reflected increased satisfaction for interactive class sessions. After receiving this feedback, teachers incorporated online research in the classroom by having students explore descriptions, symptoms, and treatments of mental health disorders such as seasonal affective disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. For the class session on exercise, students were provided with examples of easy physical stretches and activities to meet fitness goals. Teachers also implemented movement, such as class stretching or mindfulness exercises, into class lessons.

At the end of the course, responses to student class session and interviews of key stakeholders were analyzed. Interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed with key stakeholders at ALP (i.e., executive director, student services coordinator, and program manager). In addition, a health literacy nurse leader at Providence Hospital in Anchorage who provided training for the PLNs was interviewed.

Qualitative analysis of key stakeholder interviews, student statements obtained from end-of-class worksheet responses, and mid-course and final course evaluations were performed by three members of the Health in the English Language project team. Initially, data were coded independently by each of the researchers to identify themes. Thematic analysis using Van Manen's (1990) approach of identifying specific phrases then was used. Dependability of results was achieved through independent research review and examination of themes by the research team to develop consensus.

Results

The purpose of the project was to implement the social view of health literacy in a community-centered health literacy curriculum for ELL students at ALP. Evaluative methods and community member statements demonstrated the experiences of the students, ALP, and the community. In-class evaluation indicated potential impacts on the students, and interviews with key stakeholders provided feedback on the significance of the Health in the English Language course on the community.

Based on the analysis of student end-of-class worksheet responses and evaluation, themes emerged in student learning outcomes. The main themes that students reported in “I can . . .” statements were managing health care and medications, and learning new words. “I want to learn . . .” statements consisted of the same themes as “I can . . .” statements, with the addition of making healthy eating decisions. Students reported managing health care and medications as the most important topic. Final course feedback found that the least favorite topics in the class were physical activity and first aid. Students showcased their confidence by being able to answer evaluation prompts using new words and concepts. In addition, they were able to engage in conversation on topics. This was highlighted at the health fair when they talked one-on-one with community partners.

Staff members and community partners provided feedback about the program by describing its ability to affect student knowledge and confidence, ALP, and the Anchorage community. Linda Shepard, a nurse from Providence hospital, said that “the hands-on nature of the curriculum . . . [was] very engaging.” The course was able to address students' needs and capture student interests simultaneously. Student Support Coordinator Amy Facklam said students from the course told her “that what they learned was important to them” because they were able to practice both health literacy and English. Students were engaged in active learning experiences that aimed to increase their knowledge of healthy behaviors.

According to ALP Executive Director, Polly Smith, the course brought “new energy to a program that lost the joy and value in teaching health literacy.” She also mentioned the fact that “the energy [the course leaders] brought rein-vigorated the students” and ultimately influenced people at ALP to learn more about promoting healthy behaviors. Facklam said the course “was a benefit to the community because [the course leaders] reached out to the community and brought their attention to students at ALP who aren't getting the health care they should or aren't aware of how to get the health care they should.” Because of the course, ALP became aware of the issue of health literacy.

The Health in the English Language course also affected the greater Anchorage community. Marisol Vargas, a Program Manager and former ALP student, emphasized the course leaders' use of the PLNs. Vargas noted PLNs were able to provide a perspective of people who “learned the language and . . . see it another way. When [one's] first language is English, [he or she] might not see things in a similar way.” Working with PLNs was a way in which the course leaders were able to interact with people in Anchorage and understand their lives. Many PLNs thanked the program leaders for implementing the program and listening to feedback.

The course concluded with a health fair that included the following community health organizations: Anchorage Neighborhood Health Center, Planned Parenthood, YMCA, Anchorage Project Access, Providence Hospital, Anchorage City Health Department, and Women, Infant, and Children nutrition program. The organizations came into the classroom for the health fair, which allowed course participants to interact with them. These organizations recognized the need to work with ALP students in the future as well as how to work with ELL students and immigrant communities to promote healthy behaviors. ALP Executive Director Polly Smith recognized that students learning about the community also were able to share their knowledge with their families, creating a “ripple effect” and allowing the course to expand “far beyond the individual” in spreading health knowledge. The social view of health literacy not only provided students and community organizations benefits from direct engagement, but also allowed for a gain in health knowledge by people involved indirectly.

Overall, the Health in the English Language course was able to involve all students, which Student Support Coordinator Amy Facklam described as extremely important when teaching adults. She said partnering with university students enabled ALP to take “a very difficult concept and give students a place to use it . . . in the real world.” Many of the staff members at ALP also mentioned having the course serve as a model that can be replicated elsewhere. The key informant interviews, in conjunction with the student evaluations, exhibited an increase in health literacy awareness and knowledge.

Lessons Learned

ALP students and staff, community organizations, and course leaders identified community engagement and partnerships with community services that support health as powerful learning tools for health literacy. The practical application provided participants with real-life examples of how they and people in their social network can be healthy. The integration of a university-sponsored community program benefited the course participants, community organizations, and the university students.

ALP students were given the opportunity to learn English through the lens of health, which allowed them to improve both their English language skills and health care knowledge. Students learned everyday life skills, such as eating healthy and exercising, reading prescription and nutrition labels, and scheduling medical appointments. The use of outside resources in the classroom allowed for relatability and skill-building during class sessions. Students received contact information of health resources related to each class topic so that they could access community health organizations. Providing resources directly to students through classroom interaction therefore enabled direct communication and allowed students to apply their skills in real-life settings. Working with the community to develop the course greatly expanded the student benefits of the course.

The community partners contributed to the program's success through their interest in adult basic education, recognition of the unique needs of ELL students, and willingness to address health literacy levels. This was seen through the community organizations not only learning from their experience at the health fair, but also gaining ideas for future local health programming to address the needs of ALP's students. The connections made helped health organizations in Anchorage recognize ALP as a valuable partner. In the future, the course plans to integrate Anchorage community partners into lessons in the classroom on a weekly basis to work with the students, understand their learning needs, and serve as an ongoing resource. The community gained awareness of ALP's students and were able to engage them effectively on the issue of health illiteracy. Upon returning home from Alaska, the students and faculty wrote this manuscript and presented their work and lessons learned to other Georgetown University students.

The pilot program was successful in forging a partnership between university students and community members in Anchorage. To sustain and build on the relationship with ALP, two new undergraduates were recruited and were trained to go to Anchorage, Alaska during the summer of 2019 to implement the curriculum and further develop partnerships with community organizations. The university students anticipate using the knowledge gained from this experience in their health care careers.

The undergraduate students who taught the course gained valuable skills in program design and implementation, evaluation, community building, curriculum planning, and project execution. They also learned about community health education efforts. The students applied what they learned in the classroom to the real-world setting by creating an effective health intervention to address the problem of health literacy. The course leaders were able to deliver excitement and energy toward the health literacy topics through a curriculum plan tailored to ALP students' particular needs.

Overall, this university and community partnership accomplished its goal of expanding health literacy knowledge among students, nonprofit organizations, and community organizations. Community involvement was a main pillar of success of this program. Coupled with interactive activities, the course was both effective and exciting for ELL students. Course participants were able to learn valuable skills in a lively, community-oriented fashion, which expanded their knowledge of health topics and available resources. All of the organizations involved benefited through exposure and knowledge, which expanded overall community health because the students and community partners were able to share class information with other people in their social network.

ALP used the health literacy program to expand its focus on both comprehension of English and health, as well as its connections with community organizations to improve student health outcomes. The health literacy program described in this article can be replicated by other university students to expand their knowledge and create meaningful experiential learning opportunities positively affecting communities facing health disparities. The curriculum used was successful and can be adapted by other literacy organizations to fit the culture and characteristics of their community. We hope the Health in the English Language course continues at ALP in the future and expands to other organizations dedicated to improving literacy in communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Alaska Literacy Program (ALP); ALP staff members Polly Smith, Amy Facklam, and Marisol Vargas; and Linda Shepard, a health literacy expert at Providence Hospital, Anchorage, Alaska.

References

- Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. (2018). Healthy Alaskans 2020 scorecard. Retrieved from http://hss.state.ak.us/ha2020/assets/HA2020_Scorecard_2018.pdf

- Berkman N. D. Sheridan S. L. Donahue K. E. Halpern D. J. Crotty K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97–107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Applied Linguistics. (2019a). BEST literacy. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/aea/bl/

- Center for Applied Linguistics. (2019b). BEST Plus 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/aea/bp/.

- Data Recognition Corporation. (2018). Tests of Adult Basic Education. Retrieved from https://tabetest.com

- De Wit L. Fenenga C. Giammarchi C. di Furia L. Hutter I. de Winter A. Meijering L. (2017). Community-based initiatives improving critical health literacy: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health, 18, 40. 10.1186/s12889-017-4570-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacio E. V. (2013). Health literacy and community empowerment: It is more than just reading, writing and counting. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(8), 1056–1068. 10.1177/1359105312470126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I. Frijters J. Johnson-Lawrence V. Greenberg D. Nightingale E. Moodie C. (2016). Examining associations between health information seeking behavior and adult education status in the U.S.: An analysis of the 2012 PIAAC Data. PloS One, 11(2), e0148751. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Gutiérrez M. Bas-Sarmiento P. Albar-Marin M. J. Paloma-Castro O. Romero-Sanchez J.M. (2018). Health literacy interventions for immigrant populations: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 65(1), 54–64. 10.1111/inr.12373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D. A. Bess K. D. Tucker H. A. Boyd D. L. Tuchman A. M. Wallston K. A. (2009). Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 446–451. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans M. Waverijn G. Rademakers J. van der Vaart R. Rijken M. (2015). Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance for self-management. Patient Education & Counseling, 98(1), 41–48. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan R. A. Wong W. F. Villaire M. Daus G. Parnell T. A. Willis E. Paasche-Orlow M. K. (2015). Health literacy: A necessary element for achieving health equity. Retrieved from National Academy of Medicine website: https://nam.edu/perspectives-2015-health-literacy-a-necessary-element-for-achieving-health-equity/

- Mas F. S. Mein E. Fuentes B. Thatcher B. Balcázar H. (2013). Integrating health literacy and ESL: An interdisciplinary curriculum for Hispanic immigrants. Health Promotion Practice, 14(2), 263–273. 10.1177/1524839912452736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack L. Thomas V. Lewis M. A. Rudd R. (2017). Improving low health literacy and patient engagement: A social ecological approach. Patient Education & Counseling, 100(1), 8–13. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–267. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion. (2008). America's health literacy: Why we need accessible health information. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website: https://health.gov/communication/literacy/issuebrief/

- Papen U. (2008). Literacy, learning and health—A social practices view of health literacy. Literacy & Numeracy Studies, 16(2), 19–34. 10.5130/lns.v0i0.1275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M. G. Handley M. A. Omark K. Schillinger D. (2014). ESL participation as a mechanism for advancing health literacy in immigrant communities. Journal of Health Communication, 19(Suppl. 2), 89–105. 10.1080/10810730.2014.934935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K. Van den Broucke S. Fullam J. Doyle G. Pelikan J. Slonska Z. Brand H. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 80. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squiers L. Peinado S. Berkman N. Boudewyns V. McCormack L. (2012). The health literacy skills framework. Journal of Health Communication, 17(Suppl. 3), 30–54. 10.1080/10810730.2012.713442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens S. (2015). Preventing 30-day readmissions. Nursing Clinics of North America, 50(1), 123–137. 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V. M. Coronado G. Acorda E. Teh C. Tu S.-P. Yasui Y. Hislop T. G. (2008). Development of an ESL curriculum to educate Chinese immigrants about hepatitis B. Journal of Community Health, 33(4), 217–224. 10.1007/s10900-008-9084-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh J. Y. Sentell T. Gildengorin G. Le G. M. Chan E. Fung L. C. Nguyen T.T. (2016). Healthcare communication barriers and self-rated health in older Chinese American immigrants. Journal of Community Health, 41(4), 741–752. 10.1007/s10900-015-0148-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]