Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterized by the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–dependent differentiation of lung fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, leading to excessive deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, which distort lung architecture and function. Metabolic reprogramming in myofibroblasts is emerging as an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of IPF, and recent evidence suggests that glutamine metabolism is required in myofibroblasts, although the exact role of glutamine in myofibroblasts is unclear. In the present study, we demonstrate that glutamine and its conversion to glutamate by glutaminase are required for TGF-β–induced collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts. We found that metabolism of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate by glutamate dehydrogenase or the glutamate-pyruvate or glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminases is not required for collagen protein production. Instead, we discovered that the glutamate-consuming enzymes phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 18A1 (ALDH18A1)/Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) are required for collagen protein production by lung fibroblasts. PSAT1 is required for de novo glycine production, whereas ALDH18A1/P5CS is required for de novo proline production. Consistent with this, we found that TGF-β treatment increased cellular concentrations of glycine and proline in lung fibroblasts. Our results suggest that glutamine metabolism is required to promote amino acid biosynthesis and not to provide intermediates such as α-ketoglutarate for oxidation in mitochondria. In support of this, we found that inhibition of glutaminolysis has no effect on cellular oxygen consumption and that knockdown of oxoglutarate dehydrogenase has no effect on the ability of fibroblasts to produce collagen protein. Our results suggest that amino acid biosynthesis pathways may represent novel therapeutic targets for treatment of fibrotic diseases, including IPF.

Keywords: fibroblast, pulmonary fibrosis, cellular metabolism, glutamine

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, fatal disease that has a median survival of 3.5 years and affects approximately 89,000 people in the United States (1, 2). A defining feature of IPF is the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–dependent differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts (3, 4). Upon TGF-β exposure, lung fibroblasts alter their gene expression profile with de novo expression of cytoskeletal and contractile proteins normally found within smooth muscle cells and of extracellular matrix proteins including collagen (5, 6).

Metabolic reprogramming in fibroblasts by TGF-β is an emerging mechanism required for myofibroblast differentiation and matrix production (7, 8). We have recently demonstrated that myofibroblasts use metabolism of glucose to support de novo production of glycine, a nonessential amino acid that constitutes over one-third of the primary structure of collagen protein (9, 10). Glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in blood, has recently been shown to be required for myofibroblast differentiation and collagen protein production; however, the mechanisms behind this requirement are not fully understood (11–13).

Glutamine and its conversion to α-ketoglutarate play an important anaplerotic role, replenishing the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) cycle and thus supporting cellular energy production and biosynthetic reactions (14, 15). This process, termed “glutaminolysis,” first involves the conversion of glutamine to glutamate by glutaminase (GLS). Glutamate is then converted to α-ketoglutarate by either glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD) or aminotransferases, including the glutamate-pyruvate transaminases (GPT1, GPT2), glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminases (GOT1, GOT2), or phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT1) (14, 15). In addition to anaplerotic reactions, glutamine-derived glutamate can support de novo proline synthesis through the action of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS), encoded by the ALDH18A1 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 18A1 gene), which converts glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C), which is then converted to proline by P5C reductases (PYCR1, PYCR2, and PYCRL) (16).

In the present study, we demonstrate that production of collagen protein in TGF-β–treated fibroblasts is dependent on glutamine and its conversion to glutamate by GLS. Surprisingly, glutamine did not contribute to cellular oxygen consumption, and oxidative metabolism of α-ketoglutarate by oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) is not required for collagen protein production. Instead, we found that glutamate metabolism through PSAT1 and ALDH18A1/P5CS is required for collagen protein production, suggesting a prominent role of glutamine in promoting amino acid biosynthesis for matrix production.

Methods

Fibroblast Culture

Normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLFs) (Lonza) were cultured as previously described (9). For most experiments, cells were serum starved in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Corning) containing 0.1% BSA, 25 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 6 mM glutamine for 24 hours before treatment with TGF-β (1 ng/ml; MilliporeSigma). We also tested the effect of different concentrations of glutamine (2–6 mM) in a separate set of experiments. For glutamine starvation experiments, cells were washed with PBS before replacement with Gibco glutamine-free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 0.1% BSA with or without 6 mM glutamine. N,N′-[thiobis(2,1-ethanediyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole-5,2-diyl)]bisbenzeneacetamide (BPTES) (Tocris Bioscience), CB-839 (Cayman Chemical), and aminooxyacetic acid (AOA) (Sigma-Aldrich) were added at the time of TGF-β treatment.

siRNA Knockdowns

For siRNA knockdowns, 1 × 106 normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLFs) were transfected with 250 pmol ON-TARGETplus siRNA (Dharmacon). Cells were plated on 10-cm dishes for 24 hours and then replated for experiments as described above. For a list of siRNAs used, see the data supplement.

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed, and electrophoresis was performed as we previously described (9). For a list of primary antibodies used, see the data supplement.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Plus (Zymo Research) and reverse transcribed using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Quantitative mRNA expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For a list of primers used, see the data supplement.

Metabolic Assays

NHLFs treated with TGF-β for 48 hours were replated onto Seahorse XFe24 plates (Agilent Technologies) at 3 × 104/well. Media were replaced with DMEM (Agilent Technologies) supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine (omitted for glutamine-free wells), and 1 mM pyruvate. Inhibitors used were oligomycin A (1 μM), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; 2 μM), and antimycin/rotenone (1 μM each).

Metabolomic analysis was performed on lysates from NHLFs treated with TGF-β or left untreated for 48 hours. Cells were plated on 10-cm dishes at 1.25 × 106 and treated as described above. Samples were processed by Human Metabolome Technologies America.

Lung Tissue Samples

Collection and use of human lung specimens was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Lung tissues from patients with IPF who underwent lung transplant and lung tissues from donors were used. Use of animals was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at the University of Chicago. C57BL/6J mice were intubated, and bleomycin (1 IU/kg; Fresenius Kabi) was intratracheally instilled. Mice were killed after 21 days.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t test for comparisons between two samples or by one-way ANOVA using Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Glutamine and GLS Are Required for TGF-β–induced Production of Collagen Protein in Lung Fibroblasts

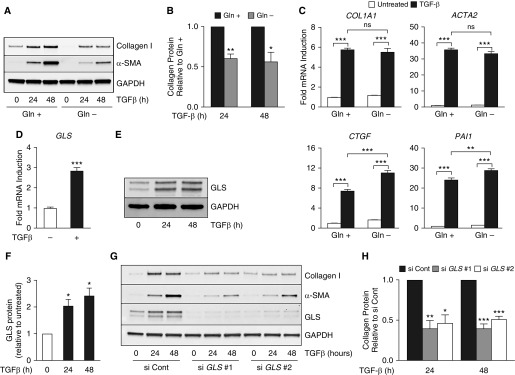

In agreement with recent reports (11), we found that culturing NHLFs in the absence of glutamine inhibited TGF-β–induced production of collagen protein and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Figures 1A and 1B). Collagen protein induction by TGF-β was similar at 6 mM and 2 mM glutamine. However, collagen induction was reduced at lower glutamine concentrations (Figure E1 in the data supplement). Notably, glutamine did not affect TGF-β–induced mRNA expression of COL1A1 (collagen type I, α1), ACTA2 (α-SMA) or that of the SMAD target genes CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) or PAI1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1), suggesting that signaling downstream of TGF-β receptor is not dependent on glutamine (Figure 1C). We found that the mRNA and protein expression of GLS, the first enzyme in the glutaminolysis pathway, was induced by TGF-β treatment in NHLFs, suggesting an important role for GLS in myofibroblast differentiation (Figures 1D–1F). We thus knocked down GLS using two independent siRNAs and treated the cells with TGF-β. GLS knockdown significantly reduced collagen protein accumulation downstream of TGF-β (Figures 1G and 1H). Similar results were seen in cells treated with the GLS inhibitors BPTES or CB-839 (Figure E2).

Figure 1.

Glutamine (Gln) and glutaminase (GLS) are required for transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–induced collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts. (A) Western blot analysis of collagen I and α-SMA protein concentrations in normal human lung fibroblasts (NHLFs) treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of Gln as indicated. (B) Quantification of collagen concentrations in A is normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the presence of Gln (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) qRT-PCR measurement of mRNA expression of COL1A1 (collagen type 1, α1); ACTA2 (α-SMA gene); CTGF (connective tissue growth factor); and PAI1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1). NHLFs were treated with TGF-β for 24 hours or left untreated in the presence or absence of Gln (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) mRNA expression of GLS measured by qRT-PCR. NHLFs were treated with TGF-β for 24 hours or left untreated (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (E) Western blot analysis of GLS protein concentrations in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (F) Quantification of collagen concentrations in E normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in untreated cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (G) Western blot analysis of collagen I, α-SMA, and GLS protein concentrations in control and GLS-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (H) Quantification of collagen concentrations in G normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. α-SMA = α-smooth muscle actin; ns = not significant; si Cont = non-targeting control siRNA.

GLUD, GPTs, and GOTs Are Not Required for Collagen Protein Production in Lung Fibroblasts

To act as an anaplerotic substrate, glutamate must be converted to the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate by either GLUD or aminotransferases (Figure 2A). Because GPTs (GPT1, GPT2) and GOTs (GOT1, GOT2) each have a mitochondrially localized enzyme (GPT2, GOT2), we focused on these enzymes in addition to GLUD as possible mechanisms by which glutamine contributes to anaplerosis in NHLFs. TGF-β induced the mRNA expression of GPT2, GOT1, and GOT2 in NHLFs (Figure 2B). Protein expression of these enzymes was also induced by TGF-β (Figure 2C). Conversely, GLUD protein expression was reduced by TGF-β treatment (Figure 2C). We were unable to detect GPT1 protein in lung fibroblasts using multiple antibodies (data not shown). To determine whether these enzymes are required for TGF-β–induced collagen protein production, we knocked down each enzyme using two independent siRNAs. Surprisingly, our results demonstrate that the expression of GLUD, GPT2, GOT1, or GOT2 is not required for myofibroblast differentiation or collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts (Figures 2D–2H).

Figure 2.

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD), glutamate-pyruvate transaminases (GPTs), and glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminases (GOTs) are not required for TGF-β–induced collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts. (A) Schematic representation of the biochemical reactions performed by GLUD, GPT, and GOT while converting glutamate to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG). (B) mRNA expression of GLUD, GPT1, GPT2, GOT1, and GOT2 measured by qRT-PCR. NHLFs were treated with TGF-β for 24 hours or left untreated (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) Western blot analysis of GLUD, GPT2, GOT1, and GOT2 protein concentrations in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (D–G) Western blot analysis of collagen I and α-SMA protein concentrations in control or GLUD- (D), GPT2- (E), GOT1- (F), and GOT2-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals (G). (H) Quantification of collagen concentrations in D–G normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Ala = alanine; Asp = aspartate; Glu = glutamate; OAA = oxaloacetate; Pyr = pyruvate.

PSAT1 Is Required for Collagen Protein Production in Lung Fibroblasts

Although knockdown of GPT or GOT enzymes had no effect on collagen protein production in NHLFs, we found that treatment of cells with the pan-transaminase inhibitor AOA (Aminooxyacetic acid) inhibited TGF-β–induced collagen protein accumulation (Figures 3A and 3B). Although there is no mitochondrial isoform of PSAT1, PSAT1 has been shown to be a significant source of cellular α-ketoglutarate in breast cancer cells as well as in mouse embryonic stem cells (17, 18). Furthermore, PSAT1 produces 3-phosphoserine, an intermediate of the de novo serine and glycine synthesis pathway, a pathway that we have previously shown is required for collagen protein production by myofibroblasts (9, 10) (Figure 3C). We found that PSAT1 mRNA and protein expression was significantly upregulated by TGF-β treatment in NHLFs (Figures 3D and 3E). Furthermore, knockdown of PSAT1 using two independent siRNAs inhibited collagen protein production downstream of TGF-β (Figures 3F and 3G). Similar results were found in primary lung fibroblasts obtained from two patients with IPF (Figures E3A and E3B).

Figure 3.

Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) is required for TGF-β–induced collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts. (A) Western blot analysis of collagen I and α-SMA protein concentrations in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals in the presence or absence of aminooxyacetic acid (AOA; 2 mM). (B) Quantification of collagen concentrations in A normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the absence of AOA (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) Schematic representation of the biochemical reaction performed by PSAT1 while converting glutamate to α-KG. (D) mRNA expression of PSAT1 measured by qRT-PCR. NHLFs were treated with TGF-β for 24 hours or left untreated (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (E) Western blot analysis of PSAT1 in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (F) Western blot analysis of collagen I, α-SMA, and PSAT1 protein concentrations in control and PSAT1-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (G) Quantification of collagen concentrations in F normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Conversion of Glutamate to Proline Is Required for Collagen Protein Production in Lung Fibroblasts

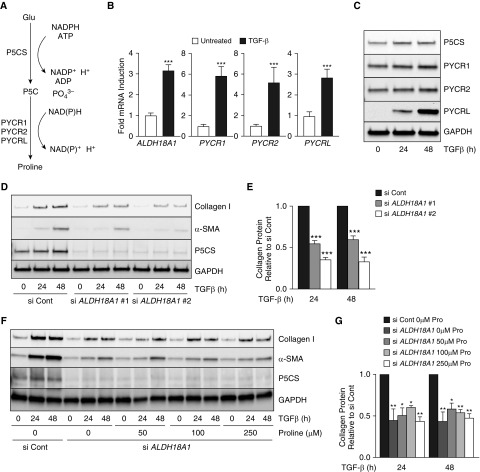

In addition to its role in anaplerosis, glutamate is an important precursor for proline, an amino acid that, together with glycine, constitutes more than 50% of the primary structure of collagen protein (16). Conversion of glutamate to proline requires the action of P5CS, encoded by the ALDH18A1 gene, which converts glutamate to P5C. P5C is then converted to proline by P5C reductases (PYCR1, PYCR2, and PYCRL) (Figure 4A). We found that mRNA and protein expression of all of the enzymes of the de novo proline synthesis pathway are upregulated by TGF-β treatment in NHLFs (Figures 4B and 4C). To determine whether conversion of glutamate to proline is required for collagen protein production by lung fibroblasts, we knocked down ALDH18A1 using two independent siRNAs. Knockdown of ALDH18A1 significantly inhibited collagen protein production induced by TGF-β (Figures 4D and 4E). Because our experiments were performed in DMEM, a medium that contains no proline, we cultured cells with ALDH18A1 knockdown in medium supplemented with increasing concentrations of proline within the physiological range. Supplementation with extracellular proline did not rescue collagen protein production in the absence of ALDH18A1, suggesting that de novo synthesis of proline is required to support collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts (Figures 4F and 4G). Similar results were found in primary lung fibroblasts obtained from two patients with IPF (Figures E3C and E3D).

Figure 4.

De novo proline synthesis is required for collagen protein production in lung fibroblasts. (A) Schematic representation of the biochemical reactions required for de novo proline production from Glu. (B) mRNA expression of ALDH18A1 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 18A1) or pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (PYCR1, PYCR2, or PYCRL) measured by qRT-PCR. NHLFs were treated with TGF-β for 24 hours or left untreated (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) Western blot analysis of P5CS (Δ-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase), PYCR1, PYCR2, and PYCRL protein concentrations in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (D) Western blot analysis of collagen I, α-SMA, and P5CS protein concentrations in control and ALDH18A1-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (E) Quantification of collagen concentrations in D normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (F) Western blot analysis of collagen I, α-SMA, and P5CS protein concentrations in control and ALDH18A1-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals in the presence of the indicated concentrations of proline. (G) Quantification of collagen concentrations in F normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. NADPH = reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Glutamine Metabolism Is Not Required to Support Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption in Lung Fibroblasts

Metabolic reprogramming in lung fibroblasts downstream of TGF-β is associated with increased mitochondrial oxygen consumption (8). Because glutamine is an anaplerotic substrate, we examined whether glutamine metabolism is required for increased mitochondrial oxygen consumption induced by TGF-β in NHLFs. Using the Mito Stress Test kit with the Seahorse XF24 analyzer (Agilent Technologies), we measured cellular oxygen consumption rate at baseline, coupled respiration (after injection of oligomycin A), and maximal respiration (after uncoupling with FCCP). Nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption was then subtracted after injection of antimycin A and rotenone. We found that TGF-β treatment increased basal mitochondrial oxygen consumption, whereas FCCP-stimulated maximal oxygen consumption rate was unaffected by TGF-β (Figures 5A and 5B). Interestingly, we found that culturing TGF-β–stimulated cells in the absence of glutamine had no effect on cellular oxygen consumption (Figures 5A and 5B). Similar results were seen when TGF-β–stimulated cells were treated with the GLS inhibitors (BPTES or CB-839) or with the aminotransferase inhibitor AOA (Figure E4).

Figure 5.

Glutaminolysis is not required to support mitochondrial oxygen consumption in lung fibroblasts. (A) Analysis of cellular oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for 48 hours or left untreated. OCR was measured in the presence or absence of Gln. Cells were treated with oligomycin A, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), and rotenone/antimycin (R+A) as indicated. (B) Average basal and maximal OCR values from A. (C) Western blot analysis of collagen I, α-SMA, and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) protein concentrations in control and OGDH-knockdown NHLFs treated with TGF-β for the indicated intervals. (D) Quantification of collagen concentrations in C normalized to TGF-β–induced protein concentrations in the control knockdown cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (E–G) Metabolomic analysis of cellular concentrations of (E) Gln and Glu and metabolites downstream of (F) PSAT1 and (G) P5CS in NHLFs treated with TGF-β for 48 hours or left untreated. (F) 3-Phosphoserine (3P-Ser), serine (Ser), and glycine (Gly). (G) P5C and proline (Pro). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

These results suggest that glutamine is not a major oxidative substrate in lung fibroblasts and that, instead, the primary role of glutamine metabolism in lung fibroblasts is to drive biosynthetic reactions promoting the synthesis of amino acids. Thus, we knocked down expression of OGDH, the mitochondrial enzyme required for oxidative conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinyl–coenzyme A in the TCA cycle. Although OGDH knockdown inhibited mitochondrial oxygen consumption as expected (Figure E5), OGDH expression was not required for collagen protein synthesis downstream of TGF-β (Figures 5C and 5D). To determine how TGF-β regulates cellular amino acid concentrations downstream of glutamine, we conducted metabolomic analysis of control and TGF-β–treated NHLFs. Consistent with increased glutamine uptake and GLS activity, we found that cellular concentrations of glutamine and glutamate were increased in TGF-β–treated cells (Figure 5E). We found that 3-phosphoserine, serine, and glycine, amino acids downstream of PSAT1, were induced by TGF-β (Figure 5F). Similarly, P5C and proline, downstream of P5CS, were also increased by TGF-β (Figure 5G). Together, our results demonstrate that amino acid biosynthesis pathways are key effectors of the fibrogenic response to TGF-β. We did not find any effect of PSAT1 or ALDH18A1 knockdown on cellular glycolytic rate, proliferation, or survival (Figure E6).

PSAT1 and P5CS Are Highly Expressed in Fibrotic Lungs

To determine the in vivo relevance for our findings, we performed Western blot analysis on lysates from lung tissues obtained from patients with IPF during lung transplant and from healthy donors through an organ procurement organization. We found elevated concentrations of PSAT1 and P5CS in lysates from patients with IPF compared with those from normal lungs (Figures 6A and 6B). To determine whether the expression of these enzymes was increased in experimental lung fibrosis, we analyzed PSAT1 and P5CS expression in whole-lung lysates from control mice as well as mice after bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. As with IPF lung samples, PSAT1 and P5CS concentrations were increased in fibrotic mouse lungs (Figures 6C and 6D).

Figure 6.

PSAT1 and P5CS expression are elevated in fibrotic lungs. (A) Western blot analysis of PSAT1 and P5CS protein expression in lung homogenates from lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and healthy donors. (B) Quantification of A normalized to healthy lung concentrations. (C) Western blot analysis of PSAT1 and P5CS protein expression in lung homogenates from mice 21 days after intratracheal instillation of either bleomycin or PBS as a vehicle control. (D) Quantification of C normalized to saline-treated mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The defining feature of IPF is the accumulation of myofibroblasts, the primary effector cell in fibrogenesis, responsible for deposition of extracellular matrix and progressive impairment of gas exchange due to replacement of alveoli with fibrotic tissue (1, 2). The altered matrix environment of fibrotic lungs has bioactive and mechanical properties that potentiate profibrotic signaling and promote further fibroblast activation in a feed-forward cycle (19–21). Thus, inhibiting matrix production by myofibroblasts has the potential to inhibit disease progression and possibly lead to resolution (22). Although most research has focused on the signaling mediators of fibrosis, the metabolic requirements for myofibroblast activation and matrix production have recently gained research attention. Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in blood, and glutamine metabolism contributes to multiple cellular functions, including TCA cycle anaplerosis and nonessential amino acid synthesis (14, 15). Recent reports have demonstrated a requirement for glutamine for myofibroblast differentiation and matrix production; however, the exact role of glutamine in myofibroblasts is poorly understood (11, 13).

In the present study, we provide evidence that the primary role of glutamine metabolism in myofibroblasts is to promote synthesis of the nonessential amino acids, including glycine and proline, which are the two most abundant amino acids in collagen protein. We found that conversion of glutamine to glutamate by GLS is required for collagen protein production induced by TGF-β. To promote anaplerosis, glutamate can then be converted to α-ketoglutarate by the action of GLUD or aminotransferases. GLUD catalyzes a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide–dependent deamination reaction that produces ammonia (Figure 2A) (23). By contrast, aminotransferases transfer the amino group of glutamate to a ketoacid, conserving the amino nitrogen and producing an amino acid (Figure 2A) (23). Recent evidence suggests that aminotransferase activity and conservation of the amino nitrogen of glutamate are required for biomass production in proliferating cancer cells (24). Our results demonstrate that TGF-β decreases the expression of GLUD in NHLFs and that GLUD is not required for collagen protein production downstream of TGF-β. Conversely, aminotransferase expression was increased by TGF-β, and a nonselective transaminase inhibitor, AOA, was sufficient to inhibit collagen production downstream of TGF-β. Among transaminases, loss of GOT or GPT did not affect collagen protein synthesis; however, loss of PSAT1 was sufficient to inhibit collagen protein synthesis. We have previously demonstrated that collagen protein production by NHLFs requires the de novo production of glycine, using carbon derived from glucose (9, 10). Our present findings suggest that both glucose and glutamine are important precursors for glycine synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Although GOT and GPT aminotransferases were not found to be required for collagen protein production in TGF-β–stimulated fibroblasts, it remains to be determined whether these enzymes promote other aspects of myofibroblast biology.

Proline, together with glycine, constitutes over 50% of the primary structure of collagen. Proline can be synthesized de novo from glutamate, and our results suggest that de novo production of proline is required for TGF-β–induced collagen protein production. TGF-β increases the expression of all of the enzymes of the de novo proline synthesis pathway in NHLFs. We found that knockdown of P5CS, the first enzyme required for proline synthesis from glutamate, is sufficient to inhibit collagen protein production by lung fibroblasts and that addition of exogenous proline is insufficient to rescue this effect. We have previously demonstrated that collagen protein production by NHLFs occurs independent of extracellular glycine (9). Why lung fibroblasts rely on de novo production of amino acids is unknown. NHLFs may lack the specific amino acid transporters for glycine or proline. Alternatively, because the synthesis of glycine and proline is linked with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate homeostasis, the de novo production of amino acids may benefit NHLFs through modulation of cellular redox balance (16, 25, 26).

Our results suggest that although glutamine metabolism may be essential for amino acid synthesis in NHLFs, it is dispensable as an oxidative substrate for the TCA cycle and does not significantly contribute to mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Neither glutamine depletion nor pharmacologic inhibition of GLS or aminotransferases was sufficient to inhibit basal or maximal oxygen consumption in NHLFs. Furthermore, expression of OGDH is not required for collagen protein production downstream of TGF-β. Although oxidative metabolism through OGDH is the primary mechanism by which α-ketoglutarate promotes TCA cycle flux, α-ketoglutarate can be metabolized reductively through isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1, IDH2), producing isocitrate (27). Although most prominent under conditions of mitochondrial impairment, reductive α-ketoglutarate metabolism is also observed in cells with functional mitochondria and contributes to cellular redox balance (28, 29). Interestingly, quiescent human dermal fibroblasts have been demonstrated to exhibit reductive α-ketoglutarate metabolism (30).

α-Ketoglutarate may also promote myofibroblastic phenotypes through the regulation of α-ketoglutarate–dependent dioxygenases such as proline hydroxylases and the Jumonji family of histone demethylases. Hydroxylation of collagen proline residues is required to stabilize the collagen triple helix, and exogenous α-ketoglutarate promotes collagen protein stability in NHLFs (11, 31). The histone demethylase JMJD3 (Jumonji domain-containing protein 3) catalyzes the α-ketoglutarate–dependent demethylation of H3K27me3 and has been shown to regulate the expression of antiapoptotic genes in IPF fibroblasts (12). Ultimately, carbon-labeling experiments will be required to determine the fate of metabolites produced from glutamine metabolism in TGF-β–treated fibroblasts. Our results provide evidence that glycine and proline biosynthesis are two major pathways by which glutamine supports myofibroblast differentiation and matrix production; however, we do not provide direct evidence of glutamine-derived metabolite flux through these pathways or incorporation into collagen protein. These experiments would also allow for determination of the contribution of alternative substrates such as branched chain amino acids (can be converted to glutamate) and ornithine (can be converted to P5C) to collagen protein synthesis. Additional studies will also be required to determine how glutamine deprivation or deficiency of PSAT1 and P5CS may affect cellular signaling pathways or transcriptional events, which contribute to myofibroblast differentiation. These indirect effects may explain why PSAT1 and P5CS knockdown reduced α-SMA expression.

In summary, our results demonstrate that glutamine and glutamate-derived amino acid biosynthesis are required for myofibroblast differentiation and collagen protein production in human lung fibroblasts. Our results support our previous finding of the importance of de novo serine and glycine synthesis for collagen protein production and also suggest that de novo proline synthesis may be a target for IPF therapy. We also shed light on the specific pathways of glutamine metabolism used by myofibroblasts. Although either GLUD or aminotransferases produce α-ketoglutarate from glutamate, the reaction catalyzed by aminotransferases conserves the amino group of glutamate. This may be important for highly synthetic cells such as myofibroblasts. Our results suggest that aminotransferases, and PSAT1 in particular, may represent targets for therapy of IPF and other fibrotic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01ES010524, U01ES026718, W81XWH-16-1-0711 (G.M.M.), and K01AR066579; an ATS Foundation unrestricted grant; and Respiratory Health Association grant RHA2018-01-IPF (R.B.H.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design: R.B.H. and G.M.M. Acquisition of data: R.B.H., E.M.O’L., L.J.W., Y.T., G.A.G., A.Y.M., and N.O.D. Analysis and interpretation of data: R.B.H., E.M.O’L., L.J.W., G.A.G., A.Y.M., N.O.D., and G.M.M. Manuscript writing: R.B.H., E.M.O’L., and G.M.M. Final approval of the manuscript: R.B.H., E.M.O’L., L.J.W., Y.T., G.A.G., and G.M.M.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0008OC on April 11, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J, Rotella P, Esser D. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:355–361. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:1028–1040. doi: 10.1038/nm.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolters PJ, Collard HR, Jones KD. Pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:157–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheppard D. Transforming growth factor beta: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:413–417. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-008AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scotton CJ, Chambers RC. Molecular targets in pulmonary fibrosis: the myofibroblast in focus. Chest. 2007;132:1311–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie N, Tan Z, Banerjee S, Cui H, Ge J, Liu RM, et al. Glycolytic reprogramming in myofibroblast differentiation and lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1462–1474. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0780OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard K, Logsdon NJ, Ravi S, Xie N, Persons BP, Rangarajan S, et al. Metabolic reprogramming is required for myofibroblast contractility and differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:25427–25438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.646984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigdelioglu R, Hamanaka RB, Meliton AY, O’Leary E, Witt LJ, Cho T, et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β promotes de novo serine synthesis for collagen production. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:27239–27251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamanaka RB, Nigdelioglu R, Meliton AY, Tian Y, Witt LJ, O’Leary E, et al. Inhibition of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:585–593. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0186OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge J, Cui H, Xie N, Banerjee S, Guo S, Dubey S, et al. Glutaminolysis promotes collagen translation and stability via α-ketoglutarate-mediated mTOR activation and proline hydroxylation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:378–390. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0238OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai L, Bernard K, Tang X, Hu M, Horowitz JC, Thannickal VJ, et al. Glutaminolysis epigenetically regulates antiapoptotic gene expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;60:49–57. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard K, Logsdon NJ, Benavides GA, Sanders Y, Zhang J, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Glutaminolysis is required for transforming growth factor-β1-induced myofibroblast differentiation and activation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:1218–1228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman BJ, Stine ZE, Dang CV. From Krebs to clinic: glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:619–634. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Venneti S, Nagrath D. Glutaminolysis: a hallmark of cancer metabolism. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;19:163–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phang JM, Liu W, Hancock CN, Fischer JW. Proline metabolism and cancer: emerging links to glutamine and collagen. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:71–77. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy K, et al. Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature. 2011;476:346–350. doi: 10.1038/nature10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang IY, Kwak S, Lee S, Kim H, Lee SE, Kim JH, et al. Psat1-dependent fluctuations in α-ketoglutarate affect the timing of ESC differentiation. Cell Metab. 2016;24:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker MW, Rossi D, Peterson M, Smith K, Sikström K, White ES, et al. Fibrotic extracellular matrix activates a profibrotic positive feedback loop. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1622–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI71386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, et al. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:693–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinković A, Liu F, Tschumperlin DJ. Matrices of physiologic stiffness potently inactivate idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:422–430. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0335OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodcock HV, Maher TM. The treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:16. doi: 10.12703/P6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBerardinis RJ. Proliferating cells conserve nitrogen to support growth. Cell Metab. 2016;23:957–958. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coloff JL, Murphy JP, Braun CR, Harris IS, Shelton LM, Kami K, et al. Differential glutamate metabolism in proliferating and quiescent mammary epithelial cells. Cell Metab. 2016;23:867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye J, Fan J, Venneti S, Wan YW, Pawel BR, Zhang J, et al. Serine catabolism regulates mitochondrial redox control during hypoxia. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1406–1417. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Hancock CN, Fischer JW, Harman M, Phang JM. Proline biosynthesis augments tumor cell growth and aerobic glycolysis: involvement of pyridine nucleotides. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17206. doi: 10.1038/srep17206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2011;481:385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du J, Yanagida A, Knight K, Engel AL, Vo AH, Jankowski C, et al. Reductive carboxylation is a major metabolic pathway in the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:14710–14715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604572113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang L, Shestov AA, Swain P, Yang C, Parker SJ, Wang QA, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature. 2016;532:255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature17393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemons JM, Feng XJ, Bennett BD, Legesse-Miller A, Johnson EL, Raitman I, et al. Quiescent fibroblasts exhibit high metabolic activity. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stegen S, Laperre K, Eelen G, Rinaldi G, Fraisl P, Torrekens S, et al. HIF-1α metabolically controls collagen synthesis and modification in chondrocytes. Nature. 2019;565:511–515. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0874-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.