Abstract

Oxygen extraction (OEF), oxidative metabolism (CMRO2), and blood flow (CBF) in the brain, as well as the coupling between CMRO2 and CBF due to cerebral autoregulation are fundamental to brain's health. We used a clinically feasible MRI protocol to assess impairments of these parameters in the perfusion territories of stenosed carotid arteries. Twenty-nine patients with unilateral high-grade carotid stenosis and thirty age-matched healthy controls underwent multi-modal MRI scans. Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) yielded absolute CBF, whereas multi-parametric quantitative blood oxygenation level dependent (mqBOLD) modeling allowed imaging of relative OEF and CMRO2. Both CBF and CMRO2 were significantly reduced in the stenosed territory compared to the contralateral side, while OEF was evenly distributed across both hemispheres similarly in patients and controls. The CMRO2-CBF coupling was significantly different between both hemispheres in patients, i.e. significant interhemispheric flow-metabolism uncoupling was observed in patients compared to controls. Given that CBF and CMRO2 are intimately linked to brain function in health and disease, the proposed easily applicable MRI protocol of pCASL and mqBOLD imaging might serve as a valuable tool for early diagnosis of potentially harmful cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic states with the final aim to select clinically asymptomatic patients who would benefit from carotid revascularization therapy.

Keywords: Carotid stenosis, arterial spin labeling, multi-parametric quantitative blood oxygenation level dependent imaging, perfusion, cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption

Introduction

Cerebral blood flow (CBF), oxygen consumption (CMRO2), and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) are all fundamentally important indicators of brain metabolism and function. These hemodynamic and metabolic parameters may be altered in patients with steno-occlusive disease of the internal carotid artery due to a reduction of perfusion pressure in the vasculature distal to the stenosis.1 Impairments of these cerebral hemodynamic parameters in patients with high-grade carotid stenosis have been shown to predict risk for stroke,2,3 chronic vascular brain damage4,5 and cognitive impairment.6–8 Furthermore, the coupling between CMRO2 and CBF due to cerebral autoregulation plays a vital role to sustain brain homeostasis9 and might also be impaired in patients with stenosis of the brain supplying arteries. Identifying stenosis patients with dysfunctional cerebral hemodynamics and oxidative metabolism is thus crucial as these impairments are potentially reversible by surgical treatment.10–12 Assessing hemodynamic parameters and their coupling to metabolism appears especially important in clinically asymptomatic patients (i.e. without stroke-like symptoms) as only some of them clearly benefit from revascularization procedures in comparison to best medical treatment alone.13 Therefore, reliable quantification of cerebral perfusion and oxygen metabolism is needed for selecting patients without obvious neurological symptoms but harmful perfusion states to prevent further brain damage and stroke.

Current techniques for assessing CBF, OEF, CMRO2 and flow-metabolism coupling include positron emission tomography (15O-PET) and MRI-based techniques. Current gold standard is PET, because it provides estimates of CBF, OEF, and CMRO2 from 15O-PET, but for quantitative assessment, an additional measure of cerebral blood volume (CBV) is also needed.14 However, clinical applicability of PET is fairly limited due to its high complexity, invasiveness, cost, restricted availability, low spatial resolution, and radiation exposure. To overcome these limitations, non-invasive MRI-based techniques such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) and calibrated blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) imaging methods combined with hyperoxic and hypercapnic breathing challenges have been suggested to estimate hemodynamic and metabolic parameters.15 Disadvantages of calibrated BOLD techniques are the limited availability of gas control systems, high expenditure as well as discomfort during carbon dioxide applications in some patients and consequently high drop-out rates of patients from studies. A more tolerable and easy to implement MRI protocol relies on quantification of the BOLD effect.16–19 Multi-parametric quantitative BOLD (mqBOLD) imaging relies on separate measurements of transverse relaxation times (T2, T2*) and dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC)-based CBV to detect regional changes in the relation between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin.20,21 Thus mqBOLD imaging together with CBF from pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) allows for the calculation of semi-quantitative OEF and CMRO2 maps.21–23

We hypothesized that stenosis-related hemodynamic impairments in unilateral, clinically asymptomatic patients will induce asymmetric changes of hemodynamics and oxidative metabolism as well as interhemispheric flow-metabolism coupling. Therefore, in this study, we compared respective parameters and flow-metabolism coupling between cerebral territories of the affected and unaffected carotid arteries as well as between the right and left hemisphere in controls. The current study uses an easily applicable MRI protocol including pCASL and mqBOLD imaging in patients with clinically asymptomatic, unilateral high-grade carotid stenosis and healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 30 healthy elderly (17 females, mean of age 70.3 ± 4.8 years) and 29 patients (9 females, mean age 70.3 ± 7.0 years) with an asymptomatic, one-sided high-grade extracranial carotid artery stenosis (confirmed by duplex ultrasonography; all > 70% according to the NASCET criteria24) participated in this prospective study. The study was approved by the medical ethical board of the Klinikum rechts der Isar, in line with Human Research Committee guidelines of Technische Universität München. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the standard protocol approvals. Patients were recruited in the outpatient clinic for carotid stenoses of the Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery and Angiology of the Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, and healthy participants by word-of-mouth advertisement. Examination of every participant included medical history, basic screening for neurological and psychiatric diseases, and an MRI scan. Exclusion criteria for entry into the study were any neurological, psychiatric, or systemic diseases, clinically remarkable structural MRI (e.g. territorial stroke lesions, bleedings, or a history of brain surgery), visual impairments, severe chronic kidney disease, and MRI contraindications.

Concerning the final sample contributing to results, 6 patients and 6 healthy controls had to be excluded due to severe imaging artifacts in at least one MRI modality (by JG, SK, and CP in consensus) resulting in all analyses being conducted on 23 patients and 24 healthy participants. Table 1 reports sample characteristics in those including co-morbidities with particular focus on cerebro-vascular diseases.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

| Patients (n = 23) | Controls (n = 24) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 69.9 ± 7.5 | 70.1 ± 5.0 | 0.91 |

| Female sex (No.) (%) | 10 (43.5) | 15 (63) | 0.19 |

| Stenotic degree (% NASCET crit.) | 81.1 ± 8.0 | – | |

| No. right-/left-sided stenosis | 15/8 | – | |

| Smoking (No.) (%) | 11 (47.8) | 8 (33.3) | 0.31 |

| Mean pack-years in smokers | 35.7 ± 21.1 | 19.5 ± 16.5 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension (No.) (%) | 20 (87)a | 13 (54)a | 0.01 |

| Mean BP (mmHg, sys./dias.) | 160 ± 22a/87 ± 11 | 142 ± 20a/85 ± 7 | 0.01/0.40 |

| Body mass index | 26.1 ± 4.4 | 26.4 ± 3.1 | 0.81 |

| Diabetes (No.) (%) | 5 (22) | 2 (8) | 0.20 |

| Medication (No. of Pat.) (%) | |||

| Antiplatelets | 23 (100)a | 5 (21)a | <0.01 |

| Statins | 17 (74)a | 5 (21)a | <0.01 |

| Antihypertensives | 17 (74)a | 9 (38)a | 0.01 |

| CHD/PAOD (No.) (%) | 12 (52)a | 5 (21)a | 0.03 |

Note: Two-sample t-test for age, BP, and body mass index. Chi-squared test for remaining group comparisons.

Significant group differences p ≤ 0.05.

BP: blood pressure; CHD: coronary heart disease; PAOD: peripheral artery occlusive disease.

Imaging data acquisition

Scanning was performed on a clinical 3T Philips Ingenia MR-Scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) using a 16-channel head/neck-receive-coil. The protocol included structural MRI (MP-RAGE and FLAIR), pCASL to assess CBF, mqBOLD imaging with T2*- and T2-mapping to obtain R2′ (= ) and DSC MRI to generate relative CBV (rCBV) maps. Additionally, a contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the neck and the aortic arch vessels was performed. None of the healthy elderly showed relevant stenoses of the brain supplying arteries according to MRA.

The MRI scanning parameters were as follows:

MP-RAGE

TI/TR/TE/α=1000 ms/2300 ms/4 ms/8°; 170 slices covering the whole brain; FOV 240 × 240×170 mm3; voxel size 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3, acquisition time 5 min 59 s.

FLAIR

TR/TE/α=4800 ms/289 ms/90°; 183 slices covering the whole brain; FOV 250 × 250×183 mm3, acquisition size: 1.12 × 1.12 × 1.12 mm3 (reconstructed voxel size 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3), Turbo spin-echo (TSE) factor 167, inversion delay 1650 ms, acquisition time 4 min 34 s.

pCASL

All parameters were set according to the recommendations of the ISMRM perfusion study group.25 The labeling plane was individually planned on the basis of a phase contrast angiography (PCA) of the neck to ensure perpendicular labeling of a straight segment of both internal carotid arteries at least 2 cm distal to the stenosis. Label duration 1800 ms; post label delay 2000 ms; segmented 3D GRASE readout; four background-suppression pulses and proton density weighted (PDw) scan for normalization; TR/TE/α = 4377 ms/7.4 ms/90°; 16 slices; 3 dynamics; acquisition voxel size: 2.75 × 2.75 × 6.0 mm3 (reconstructed voxel size 2.73 × 2.86 × 6.0 mm3), TSE factor 19, EPI factor 7, acquisition time 5 min 41 s. A signal reduction of 25% was assumed due to four background-suppression pulses.26,27

mqBOLD imaging

All parameters were set as described previously.21 T2*-mapping: multi-echo-GRE, 12 echoes, TEmin = ΔTE = 5 ms, TR = 1950 ms, α = 30°, voxel size 2 × 2×3 mm3, 30 slices using an exponential excitation pulse for correction of magnetic background gradients28,29 and duplicate acquisition of k-space center to facilitate motion correction.30 T2-mapping: multi-echo-GraSE, 8 echoes, TEmin = ΔTE = 16ms, TR = 8971 ms, voxel size 2 × 2×3 mm3, 30 slices.

DSC MRI

DSC data were obtained during a bolus injection of a weight-adjusted Gd-DOTA bolus (concentration: 0.5 mmol/ml, dose: 0.1 mmol/kg, at least 7.5 mmol per subject, flow rate: 4 ml/s, injection 7.5 s after DSC imaging started) using single-shot GE-EPI, TR = 1513 ms, TE = 30ms, α = 60°, 80 dynamic scans, FOV 224 × 224×100 mm3, gap 0.35 mm, voxel size 2 × 2×3.5 mm3, 26 slices.

Imaging data preprocessing and calculation of parameter maps

For all processing procedures, we used custom MATLAB programs (MATLAB R2014a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, UCL, London, UK).

rCBV maps

DSC data were filtered using a 3D Gaussian spatiotemporal filter-kernel of 3-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) with time as the third dimension. All rCBV maps were calculated using integration of ΔR2*-curves (i.e., R2* = 1/T2*) and normalization of the mean white matter CBV to 2.5% as described previously.21,31

CBF maps

Label and control images were motion corrected, averaged, subtracted and normalized by a PDw-image.25 Resulting CBF maps were smoothed by an FWHM 3D Gaussian kernel of 5 mm.

Before analyzing CBF maps for perfusion lateralization, they were controlled for arterial transit time (ATT) artifacts, i.e. artifacts that occur when most of the labeled blood has not yet reached the capillary bed at the time point of signal read-out. This was conducted in two steps: First, unsmoothed CBF maps were visually inspected by an experienced neuroradiologist (JG), who screened for significant signal increases in precapillary arterioles and for signal drop-outs, especially in typical watershed areas. None of the CBF-maps had evidence of ATT artifacts. Second, to quantify contributions of ATT artifacts to the perfusion signal, the spatial coefficient of variation of the unsmoothed CBF-maps was analyzed. This measure was found to correlate with ATT artifacts and can therefore be used as an indicator for this kind of artifact.32 The coefficients of variation were compared both between hemispheres and between groups. Spatial covariance was not significantly different between groups (mean patients/controls: 38.71 ± 1.2/39.13 ± 2.2; two-sample-t-test: p = 0.88) and was not significantly increased on the side of the stenosis (mean affected/unaffected side: 38.3 ± 1.1/37.6 ± 1.5, paired t-test: p = 0.58), suggesting that ATT artifacts were not biasing the observed CBF reductions.

Relative OEF and CMRO2 maps

T2 and T2* maps were smoothed using a 3D Gaussian filter-kernel of 3 mm FWHM and transverse susceptibility-related relaxation rate maps (R2′) were calculated. Note that R2′ represents the reversible susceptibility-weighted relaxation component (e.g. static magnetic field inhomogeneity, slow diffusion regime) that is given by the difference of relaxation rates of gradient echo and spin echo (R2′ = ).33,34 In calibrated fMRI, the product of R2′ with TE describes the parameter M (i.e. maximal BOLD signal), whereas in mqBOLD imaging, R2′ leads to estimation of relative OEF (rOEF) according to Hirsch et al.21

| (1) |

with proton gyromagnetic ratio (γ = 2.675×108 s−1 T−1), susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and deoxygenated blood (Δχ = 0.924×10−7), and magnetic field strength (B0 = 3T). Relative CMRO2 (rCMRO2) was then derived via

| (2) |

with the arterial oxygen content according to An et al.35

Data analysis

All maps were normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space using SPM12. We excluded frontobasal and temporopolar regions (i.e. gray matter regions 11, 20, 25, 30, 34, 36, 38; see Table S1) because of susceptibility artifacts especially in T2* and rCBV parameter maps and the basal ganglia (regions 47-55) due to known iron deposits in these regions.

To validate pCASL-derived absolute CBF in the remaining gray matter regions, we compared values from 9 young healthy subjects (mean age 25.8 ± 3.2 years, 4 female) to CBF values assessed by 15O-water-PET in 13 young male subjects (26.1 ± 3.8 years) from another study36 across the same regions. To this end, mean CBF values were extracted within these regions in each hemisphere's anterior circulation using vascular territory maps of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries (Figure 2(a)).37 Maps of CBF, rOEF and rCMRO2 from patients were flipped along the mid-sagittal plane so that all hemispheres ipsilateral to the stenosis (i.e. affected side) were located on the same side and could be compared to the contralateral side (which was assumed to be the unaffected side). In controls, we compared the right versus the left hemisphere.

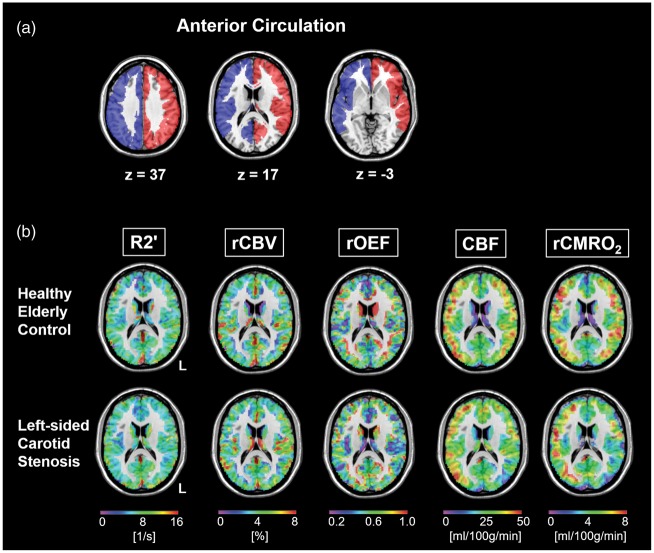

Figure 2.

Multi-parametric imaging in carotid stenosis. (a) Template of combined vascular territories of the anterior and middle cerebral artery defining the left (red) and right (blue) anterior circulation as shown earlier.37 (b) Parameter maps of R2′, rCBV, rOEF, CBF and rCMRO2 in a healthy elderly control (top row) and a left-sided carotid stenosis patient (bottom row) within gray matter in MNI space. All parameters are reasonably symmetric in the healthy subject. However, in the patient, there are reductions of CBF and rCMRO2 on the side of the stenosis, whereas R2′, rCBV and the resulting rOEF maps are quite symmetrical.

To estimate the relation between rCMRO2 and CBF for each hemisphere and to compare these individual relations between hemispheres, we linearly fitted the respective mean rCMRO2 versus CBF values across regions in each hemisphere of each participant by applying the polynomial curve fitting function (‘polyfit’) in MATLAB. Individual ratios of the fitting curves’ slopes were calculated by dividing the right by the left side's slope in controls and the affected by the unaffected hemisphere's slope in patients, respectively. In the following, this ratio is referred to as ‘interhemispheric rCMRO2-CBF coupling’.

MATLAB's ‘statistics and machine learning toolbox’ and SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, version 24.0) were used for statistical analyses. Generally, p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

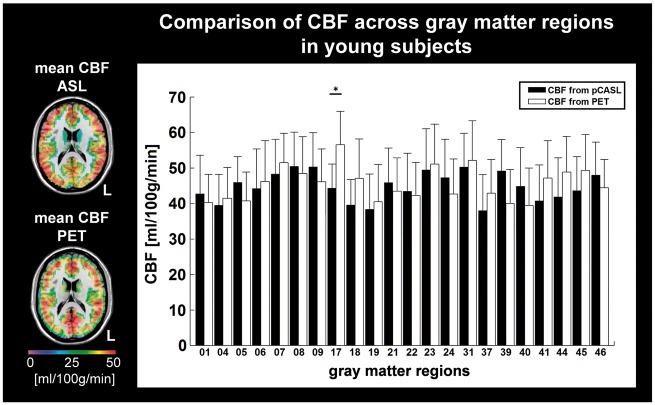

To validate the applied pCASL sequence across different brain regions, we compared absolute CBF values derived from pCASL in 9 young subjects to CBF values derived from 15O-water-PET in 13 other young healthy subjects across gray matter regions. CBF values of both modalities showed good agreement except for the visual cortex (area 17), where pCASL yielded significantly lower values (two sample t-test: p = 0.011, Figure 1). The discrepancy between 15O-water-PET and pCASL in visual cortex, which lies mainly in the territory of the posterior cerebral artery, has also been reported by others.38 This suggests that CBF measures derived by the applied pCASL are reliable in the investigated gray matter regions within the anterior circulation (Figure 2(a)).

Figure 1.

Calibration of pCASL-based CBF. Left inset: Maps of mean CBF in gray matter derived from pCASL in 9 young healthy subjects (top) and from 15O-water-PET in 13 young subjects (bottom) overlaid on a T1-weighted image in MNI space, thus allowing parcellation of gray matter space into several neuroanatomical areas (Table S1). Comparison of mean CBF from pCASL (black bars) and PET (white bars) shows good correspondence of absolute values except for region 17 (visual cortex). This discrepancy between 15O-water-PET and pCASL in visual cortex has been reported.38 *Two-sample t-test: p < 0.05.

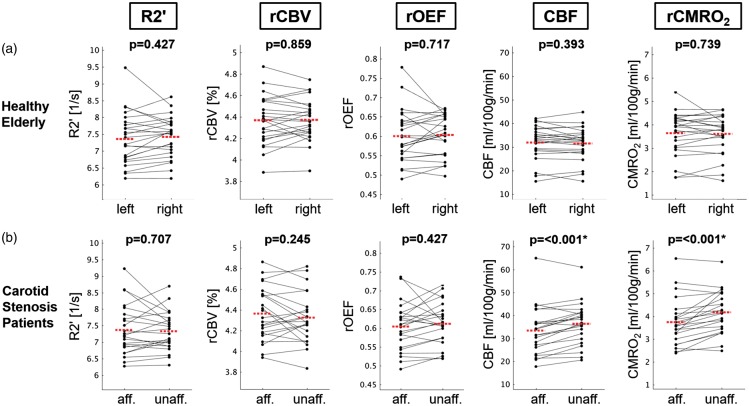

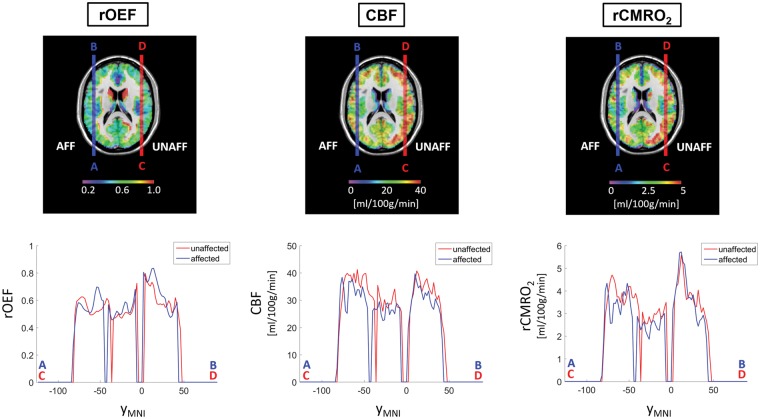

Within the validated anterior circulation regions, we compared absolute values of R2′, rCBV, rOEF, CBF and rCMRO2 (Figure 2(b)), which did not differ between patients and elderly controls on a global scale (Table 2). However, patients showed significantly reduced CBF and rCMRO2 values in the territory of the stenosed carotid artery compared to the contralateral territory (paired t-test: each p < 0.001; Figures 3 and 4). rOEF values did not differ significantly between the affected and unaffected side (Figures 3 and 4), indicating that rCMRO2 reductions on the side of the stenosis were mainly driven by CBF reductions.

Table 2.

Global hemodynamic and metabolic parameters in the anterior circulation of patients and controls.

| Patients (n = 23) | Controls (n = 24) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior circulation | |||

| R2′ [1/s] | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 7.4 ± 2.5 | 0.78 |

| rCBV [%] | 4.3 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 0.58 |

| rOEF | 0.61 ± 0.28 | 0.60 ± 0.26 | 0.62 |

| CBF [ml/100 g/min] | 34.9 ± 11.9 | 31.7 ± 9.4 | 0.07 |

| rCMRO2 [ml/100 g/min] | 4.0 ± 2.4 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 0.08 |

Note: All values in mean±SD, p-values of two-sample t-tests. R2′: transverse relaxation rate R2′ = 1/T2* – 1/T2; rCBV: relative cerebral blood volume; rOEF: relative oxygen extraction fraction; CBF: cerebral blood flow; rCMRO2: relative cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen.

Figure 3.

Comparison of averaged hemodynamic and metabolic parameters within the anterior circulation in healthy controls and patients. Paired scatter plots depicting mean R2′, rCBV, rOEF, CBF and rCMRO2 values between the (a) left versus right hemispheres in control subjects, and (b) affected (i.e. ipsilateral to the stenosis) versus unaffected (i.e. contralateral) sides of the anterior circulation in patients, respectively. Significant intra-subject side differences were observed only for CBF and rCMRO2 in patients (paired t-test, p < 0.001 for both parameters). The red dashed line indicates the mean parameter values of the respective side.

Figure 4.

Profiles of parameter maps in the affected versus unaffected hemispheres in patients. Maps of rOEF, CBF and rCMRO2 from patients were flipped along the mid-sagittal axis so that all hemispheres ipsilateral to the stenosis (i.e. affected side) were located on the same side and could be compared to the contralateral side (which was presumed to be the unaffected side). Top row shows the patients' averaged rOEF, CBF and rCMRO2 maps normalized to MNI space. The blue and red vertical lines across the images indicate the affected and unaffected hemispheres, respectively, where the profile A–B is on the affected side and the profile C–D is on the unaffected side. Bottom row: Exemplary profiles of affected (blue) and unaffected (red) hemispheres were created within an axial slice at MNI coordinate z=17 along the y-direction (yMNI) at x=−48 (affected side, blue lines and corresponding plots from A–B profile in the top row) and x=48 (unaffected side, red lines and corresponding plots from C–D profile in the top row).

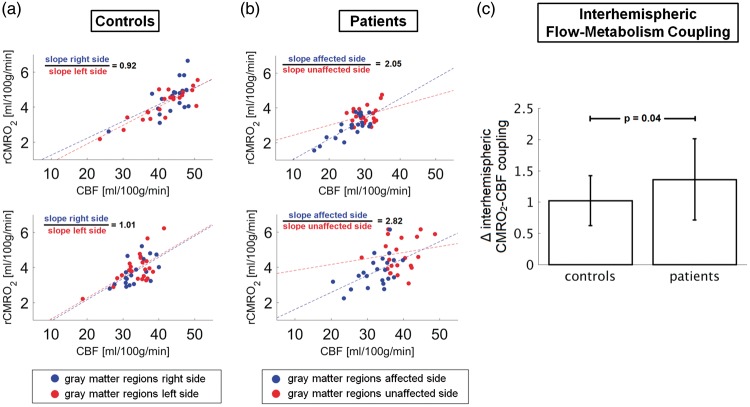

To further investigate imbalances of interhemispheric flow-metabolism coupling, we calculated the slopes of mean rCMRO2 versus mean CBF across regions for each hemisphere in each individual subject (Figure 5(a) and (b)). The mean slope in the affected/unaffected hemispheres in patients was 0.11 ± 0.04/0.09 ± 0.04 ([ml O2/ml blood], paired t-test: p = 0.023); in controls, the mean slope in the right/left hemisphere was 0.11 ± 0.04/0.11 ± 0.04 (paired t-test: p = 0.611). Individual interhemispheric coupling ratios were different between patients and controls, clearly deviating from unity in patients (mean±SD ratio of slopes in patients/controls: 1.36 ± 0.65/1.02 ± 0.40, two-sample t-test: p = 0.04, Figure 5(c)). These findings indicate imbalances of metabolic and perfusion coupling between hemispheres in unilateral carotid stenosis patients with alterations especially on the presumably unaffected side.

Figure 5.

Interhemispheric flow-metabolism coupling. Comparison of rCMRO2-CBF coupling across gray matter areas in the left (red) and right (blue) hemispheres in (a) two exemplary controls and (b) two representative patients. In (a), the rCMRO2-CBF coupling values in controls are shown for the left and right hemispheres, with red and blue circles, respectively. In (b), the rCMRO2-CBF coupling values in patients are shown for the affected (i.e. ipsilateral to the stenosis which is the right hemisphere) and unaffected hemispheres (i.e. contralateral to the stenosis which is the left hemisphere), with blue and red circles, respectively. Note that the slope ratios of the linear fitting curves for the rCMRO2-CBF coupling in each hemisphere differ more in patients (2.05 and 2.82, which correspond to 38% difference between the two patients) compared to the control subjects (0.92 and 1.01, which correspond to 10% difference between the two subjects). (c) The individual rCMRO2-CBF couplings (i.e. ratios between the fitting slopes shown in (a) and (b)) were significantly different between controls and patients (two-sample t-test: p = 0.04).

Discussion

To investigate hemodynamic and oxidative metabolic changes as well as alterations of flow-metabolism coupling due to unilateral high-grade carotid stenoses in clinically asymptomatic patients, we examined patients and healthy controls by an easily applicable MRI protocol including pCASL and mqBOLD imaging to estimate rCBV, rOEF, CBF, and rCMRO2. We found relative reductions of CBF and rCMRO2 in the affected versus the unaffected perfusion territories of the carotid arteries in patients, whereas rCBV and rOEF were unchanged. Critically, interhemispheric rCMRO2-CBF coupling was disrupted in individual patients. These results provide first evidence that high-grade carotid stenoses produce subtle but measurable effects on ipsilateral blood flow, oxidative metabolism and their coupling, even in patients without obvious neurological symptoms. The fact that these interhemispheric rCMRO2-CBF coupling ratios are measurable by MRI bears promise for future clinical application.

We revealed relative reductions of CBF and rCMRO2 in the carotid territories on the side of the stenosis compared to the unaffected side in patients, while R2′, rCBV and consequently rOEF (see equation (1)) remained stable between hemispheres (Figure 3). This finding is in line with a previous study using the mqBOLD approach in patients with severe intracranial artery stenosis demonstrating ipsilateral CBF and CMRO2 reductions, while oxygen saturation remained presumably unchanged.22 OEF increases have been reported when CBF drops below 50% in the affected side compared to the opposite side,39 which was not observed in our patient cohort (maximum relative decrease 11.6%, mean±SD = 7.6 ± 3.3%). Given stable rOEF across hemispheres, the rCMRO2 decrease on the affected side was mainly driven by CBF reductions (see equation (2)). However, absolute global values of CBF and rCMRO2 did not differ between groups (Table 2), which has also been reported by others,40 suggesting that reductions of perfusion and metabolism due to the stenosis are subtle and were evident only when comparing hemispheres within individual patients.

To further investigate the relationship of altered CBF and rCMRO2 in patients, we estimated the mean rCMRO2-CBF coupling for each hemisphere by fitting the respective parameters across different brain regions, i.e. the validated gray matter regions in the anterior circulation territory. We assessed asymmetry effects induced by unilateral carotid stenoses on rCMRO2-CBF coupling by calculating the ratio of the fitting curve slopes in the affected versus the unaffected sides in patients and the right versus the left sides in controls, respectively. Interhemispheric ratios in patients compared to controls clearly deviated from unity (mean±SD ratio of slopes in patients/controls: 1.36 ± 0.65/1.02 ± 0.40, Figure 5(c)), suggesting that high-grade stenosis not only causes absolute decreases of blood flow and oxidative metabolism but also induces asymmetric changes of their coupling at baseline. Importantly, the individual coupling slopes in carotid stenosis patients were significantly reduced in the supposedly unaffected hemisphere when compared to the affected hemisphere, the latter of which did not significantly differ from coupling slopes in healthy controls. This finding indicates that one-sided high-grade carotid stenosis leads to complex alterations of the cerebral autoregulation mechanism that might also involve the contralateral hemisphere, e.g. by shifting of blood flow from one brain hemisphere to the other via the circle of Willis, referred to as steal phenomenon.41 Several activation studies using calibrated fMRI compared evoked changes in blood flow and oxygen metabolism (ΔCBF/ΔCMRO2) and found that CBF and CMRO2 change in a near-stoichiometric manner over a wide dynamic range of activity,42,43 which can be explained by an effective diffusivity of oxygen that varies with perfusion.44 The fact that blood flow mainly regulates oxygen supply underlines the importance of an intact flow-metabolism coupling for normal brain function. Flow-metabolism coupling has been shown to be region and age dependent45 and to be impaired in diseases such as traumatic brain injury, ischemic stroke, hypertension, and Alzheimer's disease.46–48 Asymmetries between hemispheres of such coupling – as we found here in unilateral carotid stenosive disease – might therefore be an indicator of impaired autoregulation processes comprising mechanisms, utilizing mediators such as nitric oxide, astrocytes, and ion channels. Flow-metabolism uncoupling might therefore result in an inability to regulate oxygen delivery in relation to the oxidative metabolic requirements of the nerve cells and ultimately lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, neuronal death, and brain tissue atrophy.47,49 Restoration of normal flow-metabolism coupling might consequently provide a potential therapeutic target to prevent further brain damage.

There are hints that the harmful effects of chronic hypoperfusion and hypoxemia can cause brain damage and cognitive impairments. Confluent as compared to punctate leukoaraiosis is associated with cerebral hypoperfusion.4 Confluent white matter lesions are specifically linked with cognitive symptoms as reduced mental processing speed and memory performance.6–8 These findings suggest that chronic cerebral hypoperfusion is critical for brain damage ultimately leading to cognitive decline. And indeed, there is increasing evidence that suggest stenosis-associated impaired hemodynamics are relevant for cognition.50–52 Several studies investigated the effect of interventions in carotid stenosis patients on cognition with controversial results. Some report improvement of cognitive function,53–60 others did not find any or even adverse effects.61–63 However, studies investigating therapeutic effects in patients stratified into risk groups for future stroke and cognitive impairment according to their cerebral hemodynamics are sorely missing. A thorough cerebral hemodynamic assessment – as we proposed here – including rOEF, CBF, rCMRO2 as well as rCMRO2-CBF coupling might provide additional biomarkers of brain health to evaluate the risk for future events and cognitive decline. However, whether the relative reductions of CBF and rCMRO2 on the side of the stenosis as well as an interhemispheric rCMRO2-CBF uncoupling, as we revealed here, cause structural or cognitive impairments and could therefore serve as valuable biomarkers to select patients for carotid revascularization needs to be elucidated in future studies.

This study has several strengths, but also some limitations. A clear strength is the simultaneous multi-parametric assessment of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation parameters in one-sided extracranial carotid stenosis, which allows the evaluation of specific stenosis-related hemodynamic effects within subjects. A limitation, however, is that the pCASL-derived CBF might also be reduced due to an increased ATT on the side of the stenosis. To minimize this effect, we used several strategies. We applied a relatively long post-label delay and visually checked for typical ATT artifacts. Furthermore, we found no side difference in the spatial covariance of CBF signal, which has been shown to be an indicator for ATT artifacts.32 Furthermore, as labeling efficiency is dependent on flow velocity, which can be increased distal to a stenosis, label efficiency might be reduced. To prevent this, a PCA survey was used to position the labeling plane at least 20 mm cranial to the stenosis, where mean flow velocity is not supposed to be significantly increased.64 Morevoer, there is a high variability of carotid perfusion territories due to anatomical variants of the Circle of Willis and also recruitment of collaterals due to stenosis-associated reduced perfusion pressure. The applied masks of the anterior circulation according to Tatu et al.37 can therefore just serve as an approximation of the individual perfusion territory and does not account for individual vascular territory variations or shifts. Finally, the basal ganglia as well as frontobasal and anterior temporal regions within the anterior circulation are prone to susceptibility artifacts interfering with MRI-derived parameter maps based on T2*-weighted imaging such as mqBOLD and pCASL. Therefore, we excluded these regions and validated pCASL-derived CBF values in younger subjects by 15O-water-PET in the remaining gray matter regions of the anterior circulation. Both pCASL- and PET-derived CBF values showed high correspondence except for area 17, where pCASL yielded lower CBF, which has also been observed by others.38 However, only small parts of area 17 lie within the applied anterior circulation mask and therefore this systematic error only marginally impacts our results.

Conclusion

We found that CBF and rCMRO2 on the side of the stenosis were reduced compared to the contralateral side, whereas rCMRO2-CBF coupling significantly differed between the both hemispheres in patients. Given that CBF and CMRO2 as well as their coupling are intimately linked to brain metabolism and function in health and disease, the proposed easily applicable MRI protocol including mqBOLD, DSC, and pCASL might serve as a valuable tool to select patients, who may benefit from a more aggressive treatment in order to prevent chronic brain damage and cognitive decline.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Flow-metabolism uncoupling in patients with asymptomatic unilateral carotid artery stenosis assessed by multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging by Jens Göttler, Stephan Kaczmarz, Michael Kallmayer, Isabel Wustrow, Hans-Henning Eckstein, Claus Zimmer, Christian Sorg, Christine Preibisch and Fahmeed Hyder in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project numbers PR 1039/6-1 and SO 1336/4-1 and further supported by the Faculty of Medicine of the Technische Universität München (grant to JG: KKF E12), by the Dr.-Ing. Leonhard Lorenz-Stiftung (grant to JG: 915/15), by a postdoc fellowship for JG of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (SK). FH was supported by NIH grants (R01 MH-067528, R01 NS-100106, P30 NS-052519).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors' contributions

JG, SK, CP, and FH designed the study, acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the article. MK, IW, HHE, CZ, CS made a substantial contribution to the acquisition or analysis and interpretation of data, and critically revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Yundt KD, et al. Variability of cerebral blood volume and oxygen extraction: stages of cerebral haemodynamic impairment revisited. Brain 2002; 125(Pt 3): 595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Grubb RL, Jr, et al. Comparison of PET oxygen extraction fraction methods for the prediction of stroke risk. J Nucl Med 2001; 42: 1195–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, et al. Significance of increased oxygen extraction fraction in five-year prognosis of major cerebral arterial occlusive diseases. J Nucl Med 1999; 40: 1992–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ten Dam VH, van den Heuvel DM, de Craen AJ, et al. Decline in total cerebral blood flow is linked with increase in periventricular but not deep white matter hyperintensities. Radiology 2007; 243: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sam K, Crawley AP, Poublanc J, et al. Vascular dysfunction in leukoaraiosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 2258–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt R, Ropele S, Enzinger C, et al. White matter lesion progression, brain atrophy, and cognitive decline: the Austrian stroke prevention study. Ann Neurol 2005; 58: 610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Heuvel DM, ten Dam VH, de Craen AJ, et al. Increase in periventricular white matter hyperintensities parallels decline in mental processing speed in a non-demented elderly population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt R, Petrovic K, Ropele S, et al. Progression of leukoaraiosis and cognition. Stroke 2007; 38: 2619–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson EC, Wang Z, Britz G. Regulation of cerebral blood flow. Int J Vasc Med 2011; 2011: 823525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai N, Hatakeyama T, Okauchi M, et al. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism measurements using positron emission tomography on the first day after carotid artery stenting. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 23: e55–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIntosh BJ, Sideso E, Donahue MJ, et al. Intracranial hemodynamics is altered by carotid artery disease and after endarterectomy: a dynamic magnetic resonance angiography study. Stroke 2011; 42: 979–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang TY, Liu HL, Lee TH, et al. Change in cerebral perfusion after carotid angioplasty with stenting is related to cerebral vasoreactivity: a study using dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MR imaging and functional MR imaging with a breath-holding paradigm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 1330–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spence JD, Song H, Cheng G. Appropriate management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2016; 1: 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Martin WR, et al. Brain oxygen utilization measured with O-15 radiotracers and positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med 1984; 25: 177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulte DP, Kelly M, Germuska M, et al. Quantitative measurement of cerebral physiology using respiratory-calibrated MRI. Neuroimage 2012; 60: 582–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, He X. Blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD)-based techniques for the quantification of brain hemodynamic and metabolic properties – theoretical models and experimental approaches. NMR Biomed 2013; 26: 963–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christen T, Bolar DS, Zaharchuk G. Imaging brain oxygenation with MRI using blood oxygenation approaches: methods, validation, and clinical applications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1113–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone AJ, Blockley NP. A streamlined acquisition for mapping baseline brain oxygenation using quantitative BOLD. Neuroimage 2017; 147: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Quantitative BOLD: mapping of human cerebral deoxygenated blood volume and oxygen extraction fraction: default state. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christen T, Schmiedeskamp H, Straka M, et al. Measuring brain oxygenation in humans using a multiparametric quantitative blood oxygenation level dependent MRI approach. Magn Reson Med 2012; 68: 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch NM, Toth V, Forschler A, et al. Technical considerations on the validity of blood oxygenation level-dependent-based MR assessment of vascular deoxygenation. NMR Biomed 2014; 27: 853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouvier J, Detante O, Tahon F, et al. Reduced CMRO(2) and cerebrovascular reserve in patients with severe intracranial arterial stenosis: a combined multiparametric qBOLD oxygenation and BOLD fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2015; 36: 695–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gersing AS, Ankenbrank M, Schwaiger BJ, et al. Mapping of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen using dynamic susceptibility contrast and blood oxygen level dependent MR imaging in acute ischemic stroke. Neuroradiology 2015; 57: 1253–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke 1991; 22: 711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: a consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutsaerts HJ, Steketee RM, Heijtel DF, et al. Inter-vendor reproducibility of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling at 3 Tesla. PLoS One 2014; 9: e104108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia DM, Duhamel G, Alsop DC. Efficiency of inversion pulses for background suppressed arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 2005; 54: 366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch NM, Preibisch C. T2* mapping with background gradient correction using different excitation pulse shapes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: E65–E68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baudrexel S, Volz S, Preibisch C, et al. Rapid single-scan T2*-mapping using exponential excitation pulses and image-based correction for linear background gradients. Magn Reson Med 2009; 62: 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magerkurth J, Volz S, Wagner M, et al. Quantitative T*2-mapping based on multi-slice multiple gradient echo flash imaging: retrospective correction for subject motion effects. Magn Reson Med 2011; 66: 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kluge A, Lukas M, Toth V, et al. Analysis of three leakage-correction methods for DSC-based measurement of relative cerebral blood volume with respect to heterogeneity in human gliomas. Magn Reson Imaging 2016; 34: 410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutsaerts HJ, Petr J, Vaclavu L, et al. The spatial coefficient of variation in arterial spin labeling cerebral blood flow images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 3184–3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kida I, Kennan RP, Rothman DL, et al. High-resolution CMR(O2) mapping in rat cortex: a multiparametric approach to calibration of BOLD image contrast at 7 Tesla. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20: 847–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu CY, Herman P, Coman D, et al. Brain region and activity-dependent properties of M for calibrated fMRI. Neuroimage 2016; 125: 848–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An H, Lin W, Celik A, et al. Quantitative measurements of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen utilization using MRI: a volunteer study. NMR Biomed 2001; 14: 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyder F, Herman P, Bailey CJ, et al. Uniform distributions of glucose oxidation and oxygen extraction in gray matter of normal human brain: No evidence of regional differences of aerobic glycolysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 903–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatu L, Moulin T, Vuillier F, et al. Arterial territories of the human brain. Front Neurol Neurosci 2012; 30: 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K, Herzog H, Mauler J, et al. Comparison of cerebral blood flow acquired by simultaneous [15O]water positron emission tomography and arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1373–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie S, Hui LH, Xiao JX, et al. Detecting misery perfusion in unilateral steno-occlusive disease of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery by MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1504–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Vis JB, Petersen ET, Bhogal A, et al. Calibrated MRI to evaluate cerebral hemodynamics in patients with an internal carotid artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sam K, Small E, Poublanc J, et al. Reduced contralateral cerebrovascular reserve in patients with unilateral steno-occlusive disease. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 38: 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoge RD, Atkinson J, Gill B, et al. Linear coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in activated human cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 9403–9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyder F, Kennan RP, Kida I, et al. Dependence of oxygen delivery on blood flow in rat brain: a 7 tesla nuclear magnetic resonance study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000; 20: 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyder F, Shulman RG, Rothman DL. A model for the regulation of cerebral oxygen delivery. J Appl Physiol 1998; 85: 554–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiarelli PA, Bulte DP, Gallichan D, et al. Flow-metabolism coupling in human visual, motor, and supplementary motor areas assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 538–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ostergaard L, Engedal TS, Aamand R, et al. Capillary transit time heterogeneity and flow-metabolism coupling after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1585–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girouard H, Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol 2006; 100: 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venkat P, Chopp M, Chen J. New insights into coupling and uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and metabolism in the brain. Croat Med J 2016; 57: 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marlatt MW, Lucassen PJ, Perry G, et al. Alzheimer's disease: cerebrovascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and advanced clinical therapies. J Alzheimers Dis 2008; 15: 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silvestrini M, Paolino I, Vernieri F, et al. Cerebral hemodynamics and cognitive performance in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Neurology 2009; 72: 1062–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balestrini S, Perozzi C, Altamura C, et al. Severe carotid stenosis and impaired cerebral hemodynamics can influence cognitive deterioration. Neurology 2013; 80: 2145–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buratti L, Viticchi G, Falsetti L, et al. Thresholds of impaired cerebral hemodynamics that predict short-term cognitive decline in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 180–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antonopoulos CN, Kakisis JD, Sfyroeras GS, et al. The impact of carotid artery stenting on cognitive function in patients with extracranial carotid artery stenosis. Ann Vasc Surg 2015; 29: 457–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen YH, Lin MS, Lee JK, et al. Carotid stenting improves cognitive function in asymptomatic cerebral ischemia. Int J Cardiol 2012; 157: 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grunwald IQ, Supprian T, Politi M, et al. Cognitive changes after carotid artery stenting. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grunwald IQ, Papanagiotou P, Reith W, et al. Influence of carotid artery stenting on cognitive function. Neuroradiology 2010; 52: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin CJ, Chang FC, Chou KH, et al. Intervention versus aggressive medical therapy for cognition in severe asymptomatic carotid stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1889–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan Y, Yuan Y, Liang L, et al. Influence of carotid artery stenting on cognition of elderly patients with severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery. Med Sci Monit 2014; 20: 1461–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon BA, Sohn SW, Cheon SM, et al. Effect of carotid artery stenting on cognitive function in patients with carotid artery stenosis: a prospective, 3-month-follow-up study. J Clin Neurol 2015; 11: 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Q, Zhou M, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of carotid endarterectomy on cerebral reperfusion and cognitive function in patients with high grade carotid stenosis: a perfusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 50: 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chida K, Ogasawara K, Suga Y, et al. Postoperative cortical neural loss associated with cerebral hyperperfusion and cognitive impairment after carotid endarterectomy: 123I-iomazenil SPECT study. Stroke 2009; 40: 448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Rango P, Caso V, Leys D, et al. The role of carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy in cognitive performance: a systematic review. Stroke 2008; 39: 3116–3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heller S, Hines G. Carotid stenosis and impaired cognition: the effect of intervention. Cardiol Rev 2017; 25: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Filardi V. Carotid artery stenosis near a bifurcation investigated by fluid dynamic analyses. Neuroradiol J 2013; 26: 439–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Flow-metabolism uncoupling in patients with asymptomatic unilateral carotid artery stenosis assessed by multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging by Jens Göttler, Stephan Kaczmarz, Michael Kallmayer, Isabel Wustrow, Hans-Henning Eckstein, Claus Zimmer, Christian Sorg, Christine Preibisch and Fahmeed Hyder in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism