Abstract

Background

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a gram-negative bacterium and an oral commensal in dogs and cats, but occasionally causes serious infections in humans. Septicemia is one of the most fulminant forms, but diagnosis of C. canimorsus infection is often difficult mainly because of its very slow growth. C. canimorsus infective endocarditis (IE) is rare and is poorly understood. Since quite a few strains produce β-lactamase, antimicrobial susceptibility is pivotal information for adequate treatment. We herein report a case with C. canimorsus IE and the results of drug susceptibility test.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man had a dog bite in his left hand 3 months previously. The patient was referred to our hospital for fever (body temperature > 38 °C), visual disturbance, and dyspnea. Echocardiography showed aortic valve regurgitation and vegetation on the leaflets. IE was diagnosed, and we initially administered cefazolin and gentamycin assuming frequently encountered microorganisms and the patient underwent aortic valve replacement. C. canimorsus was detected in the aortic valve lesion and blood cultures. It was also identified by 16S ribosome DNA sequencing. Ceftriaxone were started and continued because disk diffusion test revealed the isolate was negative for β-lactamase and this case had cerebral symptoms. The patient successfully completed antibiotic treatment following surgery.

Conclusions

We diagnosed C. canimorsus sepsis and IE by extended-period blood cultures and 16S ribosome DNA sequencing by polymerase chain reaction, and successfully identified its drug susceptibility.

Keywords: Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Ceftriaxone, Drug susceptibility test, Infective endocarditis

Background

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a gram-negative bacillus found in saliva of healthy dogs and cats and is transmitted to humans principally through animal bites [1]. It can cause sepsis and other forms of infection. Here, we report a patient with sepsis and infective endocarditis (IE) caused by C. canimorsus. As C. canimorsus IE is rare and this microbe is difficult to culture, drug susceptibility is often unclear and its standard treatment regimen remains unestablished.

Case presentation

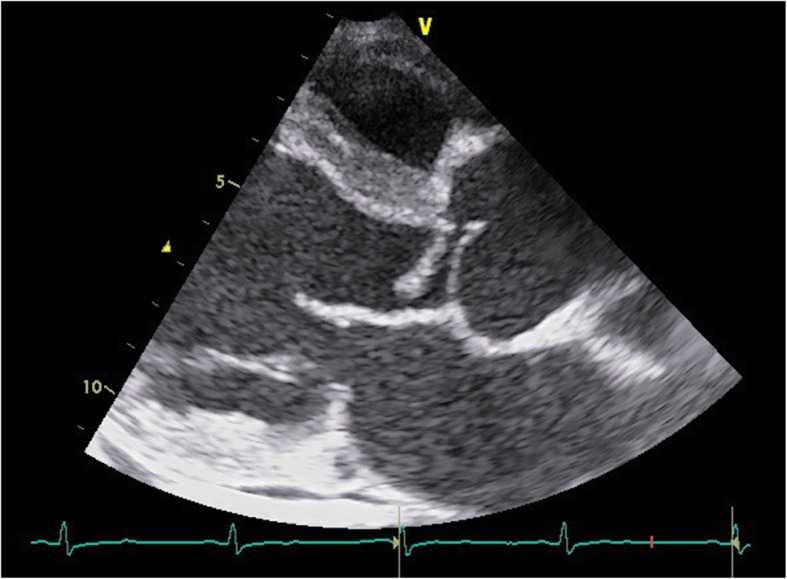

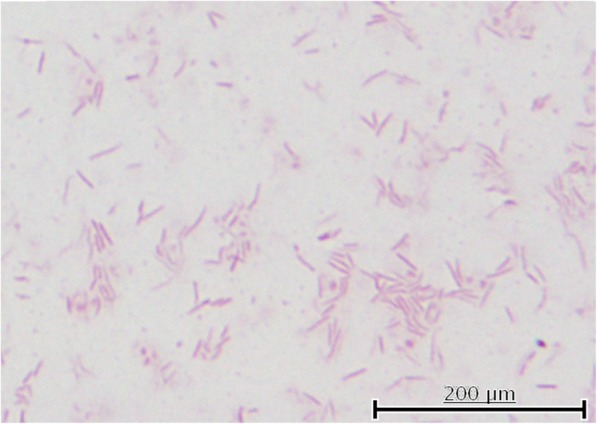

A 46-year-old man with a history of dog-bite in his left hand 3 months ago, developed fever (body temperature > 38 °C), visual disturbance, and dyspnea at rest. He had been otherwise healthy without significant medical history. He was tachycardic, and coarse crackle and diastolic heart murmur (Levine III) was audible. Laboratory test results were as follows: white blood cell count, 10,500/μL (59.8% neutrophils); hemoglobin level, 11.7 g/dL; brain natriuretic protein level, 689.2 pg/mL; and C-reactive protein level, 9.0 mg/dL (Table 1). Chest X ray showed pulmonary congestion and bilateral pleural effusion. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed no lesion in optic nerve and brain. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed moderate-to-severe aortic valve regurgitation and vegetation of 17-mm in size (Fig. 1). Seven days later, blood culture yielded Coagulase-negative staphylococci in one of four culture bottles. Although diagnosis of IE was not definitive according to Duke criteria [2], history of dog bites, his clinical course, and imaging studies suggested Staphylococcal IE. Following administration of cefazolin 6 g/day and gentamycin 3 mg/kg/day for a week, the patient underwent aortic valve replacement and resected aortic valve was negative for Staphylococci. A week following surgery, however, microorganism grew in two bottles of preoperative blood culture. This microorganism was cultured on blood agar, and gram staining of the colonies showed Capnocytophaga-like gram-negative bacilli (Fig. 2). 16S ribosome DNA sequencing both from blood and from resected heart valve identified C. canimorsus. Disk diffusion test revealed that the isolate was susceptible to almost all antimicrobial agents and did not produce β-lactamase (Table 2). The protocol of the disk diffusion test was as follows: A Brucella HK agar plate was seeded with a lawn of C. canimorsus using sterile cotton swabs. For the plate, antibiotic disks containing 10 IU of penicillin G, 10 μg/10 μg of sulbactam/ampicillin, 10 μg/100 μg of tazobactam/piperacillin, 30 μg of ceftriaxone, 10 μg of meropenem, 10 μg of gentamycin, 30 μg of amikacin, 5 μg of levofloxacin, 30 μg of minocycline, 250 μg of sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, 15 μg of clarithromycin, 2 μg of clindamycin were used with BD Sensi-Disc (BD Bioscience Co., USA) and dispensed on the agar surface. Both plates were incubated at 30 °C overnight and the diameter of each zone was measured in millimeters to evaluate susceptibility or resistance using the comparative standard method.

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| (A) Peripheal blood data | |

| Peripheral Blood | |

| WBC | 10,500 /μL |

| Neut | 59.8% |

| Lymp | 31.1% |

| Mono | 4.9% |

| Eosi | 3.9% |

| Baso | 0.3% |

| RBC | 430 × 106/μL |

| HCT | 42.0% |

| Hb | 11.7 g/dL |

| MCV | 97.7 fL |

| MCH | 32.3 pg |

| MCHC | 33.1 pg |

| PLT | 22.4 × 106/μL |

| (B) Chemistry data | |

| Chemistry | |

| TP | 6.3 g/dL |

| ALB | 4.0 g/dL |

| AST | 126 IU/L |

| ALT | 101 IU/L |

| LDH | 179 IU/L |

| γGTP | 24 U/L |

| BUN | 15 mg/dL |

| Cr | 0.71 mg/dL |

| Na | 142 mEq/L |

| K | 3.3 mEq/L |

| Cl | 107 mEq/L |

| CRP | 9.0 mg/dL |

| BNP | 689.2 pg/mL |

WBC white blood cells, Neut neutrophils, Lymp lymphocytes, Mono monocytes, Eosi eosinophils, Baso basophils, RBC red blood cells, HCT hematocrit, Hb hemoglobin, MCV mean cell volume, MCH mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, PLT platelet counts, TP total protein, ALB albumin, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase (upper limited: 211 IU/L), γ-GTP γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, Na sodium, K potassium, Cl chlorine, CRP C-reaction peptide, BNP brain natriuretic protein

Fig. 1.

Echocardiogram showing moderate-to-severe aortic valve regurgitation and vegetation of 17-mm in size

Fig. 2.

Capnocytophaga-like gram-negative bacilli on the aortic valve (× 1000)

Table 2.

Drug susceptibility shown by disk diffusion method

| Antimicrobial Agents | Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|

| Penicillin G | 32 |

| Sulbactam/Ampicillin | 36 |

| Tazobactam/Piperacillin | 38 |

| Ceftriaxone | 20 |

| Meropenem | 36 |

| Gentamycin | < 6 |

| Amikacin | < 6 |

| Levofloxacin | 34 |

| Minocycline | 40 |

| Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim | < 6 |

| Clarithromycin | 38 |

| Clindamycin | 34 |

Based on these results and symptoms, empirically selected combination of gentamycin and cefazolin was converted to ceftriaxone 4 g/day. The patient completed a total of 4 weeks of ceftriaxone. The patient has been doing well for 12 months after hospital discharge.

Discussion and conclusion

C. canimorsus is a less virulent pathogen. IE accounts for less than 2% of C. canimorsus bloodstream infection and is extremely rare [3]. Only 18 cases have been reported in the literatures since 1977 (Table 3) [4–10]. Patients were 52.8 years of age (range 24 to 73 years) on average and were predominantly male (80.0%). Affected valves were aortic in 11 (61.1%), tricuspid in six (33.3%), and mitral in four (22.2%). Nine patients (50.0%) were surgically treated, mostly using mechanical valves. Penicillin was given in eight (44.4%), and Cephalosporin in four (22.2%). Four patients (22.2%) had underlying cardiac diseases, and five (27.7%) were vulnerable to infection; alcohol abuse in four and chronic lymphocytic leukemia undergoing chemotherapy in one. Twelve of 18 patients (66.6%) had dog bite or close contact with dogs.

Table 3.

Infective endocarditis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus in literature

| No | Age/Sex | Animal contact | Underlying disease | Infected valve | Surgery (Methods) | Antibiotics | Complications | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND | Dog | ND | A | Yes (ND) | ND | ND | D | [4] |

| 2 | ND | ND | ND | A | No | ND | ND | S | |

| 3 | ND | ND | ND | M | No | ND | ND | S | |

| 4 | 64/M | Dog | ND | T, A | No | Penicillin + Erythromycin | ND | D | |

| 5 | 59/F | ND | CLL, Atrial myxoma, Steroid use | T | Yes (ND) | Cephalothin + Gentamicin | ND | D | |

| 6 | 39/M | Dog | Alcohol abuse | M | No | Ampicillin + Tobramycin | Glomerulonephritis. | S | |

| 7 | 24/M | Dog | None | A | No | Penicillin | ND | S | |

| 8 | 47/M | Dog | Alcohol abuse | T | Yes (ND) | Vancomycin + Gentamicin | ND | S | |

| 9 | 56/M | Dog | None | T | No | Penicillin + Gentamicin | ND | S | |

| 10 | 52/M | Dog | None | A | No | Penicillin + Aztreonam | ND | S | |

| 11 | 69/F | None | COPD | T | No | Penicillin | CHF | S | |

| 12 | 63/M | Dog | AVR (Mechanical valve) | A (Periannular abscess) | Yes (AVR, Tissue valve) | Penicillin | Anemia, CHF | S | |

| 13 | 41/F | Dog | Rheumatic mitral valve disease | M | Yes (MVR, Mechanical valve) | Ceftriaxone | ND | S | [5] |

| 14 | 42/M | Dog | Alcohol abuse | A | Yes (AVR, Mechanical valve) | Ceftriaxon + Gentamicin | ND | S | [6] |

| 15 | 55/M | Dog | COPD, Alcohol abuse, Intravenous drug user | A (Periannular abscess), T | Yes (AVR, Mechanical valve), (Aortoplasty) (Tricuspid valve repair) | Meropenem+ Ciprofloxacin | ND | S | [7] |

| 16 | 65/M | None | Dislipidemia | A (Periannular abscess) | Yes (Aortic root replacement, Mechanical valve) | Ampicillin + Gentamicin | Anemia, Renal insufficiency | S | [8] |

| 17 | 73/M | Dog | AVR (Mechanical valve), Diabetes, Renal insufficiency | A | No | Meropenem + Ciprofloxacin | Anemia | S | [9] |

| 18 | 43/M | Lion | None | A, M | Yes (AVR, Mechanical valve) (Mitral valve annuloplasty), (Coronary artery bypass grafting) | Ceftriaxone + Gentamicin + Vancomycin | None | S | [10] |

ND No Data, M Male, F Female, CLL Chronic Lymphocytic Lymphoma, COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, AVR Aortic valve replacement, A Aortic valve, M Mitral valve, T Tricuspid valve, MVR Mitral valve replacement, CHF Congestive heart failure, D Died, S Survived

C. canimorsus is a facultative anaerobe and grows slowly in blood culture bottles and on agar plates. It has fastidious requirements for growth (5-10% CO2) and efficient culture method has not yet been established. Diagnosis of C. canimorsus IE generally requires high indices of suspicion because clinical symptoms are non-specific and routine blood cultures are often negative. If a pet owner or an immunocompromised host develops IE and blood culture is initially negative, therefore, longer incubation or terminal subculture should be considered. In addition, Polymerase chain reaction and sequencing for 16S rDNA is useful to identify C. canimorsus [11, 12].

Since IE is a life threatening illness, antibiotic treatment often needs to be commenced before causative organism is identified. Aminoglycosides and/or β-lactam antibiotics are common empirical drugs of choice. However, almost all strains of C. canimorsus are resistant to aminoglycosides [13]. Decades ago, β-lactamase-producing Capnocytophaga was less than 2% [14], but recent papers suggest such strains have remarkably increased and account for 32% [15] or 79% [16]. So far, prognosis of C. canimorsus IE is poor chiefly due to delay in diagnosis and suboptimal drug choice. During treatment for C. canimorsus IE, therefore, addition of β-lactamase-inhibitor might be beneficial. In the present case, we chose Ceftriaxone soon after extended culture yielded gram negative bacilli. As disk diffusion test showed the strain was sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics, Ceftriaxone was continued until completion.

In conclusion, C. canimorsus is a fastidious and slow-growing microbe. C. canimorsus IE shows no specific findings but this pathogen should be kept in mind especially when pet owners show fever of unknown origin. Longer incubation along with some molecular biological diagnostic methods should be considered. Because diagnosis of C. canimorsus IE is often delayed and β-lactam tolerance is relatively common, its prognosis is not good. Prompt antimicrobial susceptibility test is essential.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IE

Infective endocarditis

Authors’ contributions

JS executed 16S rDNA sequencing, analyzed data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. KI contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and assisted in the writing of the manuscript. TM, KY, YN and HO (11th author) treated the endocarditis and bloodstream infection by surgery and using antimicrobial agents. MK, KO, SS and TK cultured the microorganisms and performed antimicrobial agent testing of C. canimorsus. SM, KI and HO (Corresponding author) finally approved the article. All authors have contributed to data collection and interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolve.

Authors’ information

Jun Sakai, MD (Saitama medical university, 2011), PhD (Saitama medical university, 2017).

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient data are disclosed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in this case report, and ethics committee of our institute approved submission and publication.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jun Sakai, Email: juntodoraemon@yahoo.co.jp.

Kazuhito Imanaka, Email: imanakaz@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Masahiro Kodana, Email: m_kodana@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Kana Ohgane, Email: o_kana@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Susumu Sekine, Email: sekine@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Kei Yamamoto, Email: yamakei_pc_mail@yahoo.co.jp.

Yusuke Nishida, Email: yushida0611@yahoo.co.jp.

Toru Kawamura, Email: toru@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Takahiro Matsuoka, Email: matsuoka@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Shigefumi Maesaki, Email: maesaki@saitama-med.ac.jp.

Hideaki Oka, Email: id-consult@hotmail.co.jp.

Hideaki Ohno, Phone: 81-49-228-3420, Email: hohno@saitama-med.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Bobo RA, Newton EJ. A previously undescribed gram-negative bacillus causing septicemia and meningitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;65:564–569. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/65.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the council on clinical cardiology, council on cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia, and the quality of care and outcomes research interdisciplinary working group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janda JM, Graves MH, Lindquist D, Probert WS. Diagnosing Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:340–342. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandoe JA. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:245–248. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frigiola A, Badia T, Lovato R, et al. Infective endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Ital Heart J. 2003;4:725–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wareham DW, Michael JS, Warwick S, Whitlock P, Wood A, Das SS. The dangers of dog bites. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:328–329. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayani O, Higginson LA, Toye B, Burwash IG. Man’s best friend? Infective endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e130–e132. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutance G, Labombarda F, Pellissier A, Legallois D, Hamon M, Bachelet C, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus endocarditis with root abscess in a patient with a bicuspid aortic valve. Heart Int. 2009;4(1):e5. doi: 10.4081/hi.2009.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalava-Karvinen P, Grönroos JO, Tuunanen H, Kemppainen J, Oksi J, Hohenthal U. Capnocytophaga canimorsus: a rare case of conservatively treated prosthetic valve endocarditis. APMIS. 2018;126:453–456. doi: 10.1111/apm.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry M. Double Native Valve Infective Endocarditis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus: First Reported Case Caused by a Lion Bite. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2018;2018:4821939. doi: 10.1155/2018/4821939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolieslager SM, Riggio MP, Lennon A, Lappin DF, Johnston N, Taylor D, Bennett D. Identification of bacteria associated with feline chronic gingivostomatitis using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Vet Microbiol. 2011;148:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross EL, Leys EJ, Gasparovich SR, Firestone ND, Schwartzbaum JA, Janies DA, Asnani K, Griffen AL. Bacterial 16S sequence analysis of severe caries in young permanent teeth. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4121–4128. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01232-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolivet-Gougeon A, Sixou JL, Tamanai-Shacoori Z, Bonnaure-Mallet M. Antimicrobial treatment of Capnocytophaga infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foweraker JE, Hawkey PM, Heritage J, Van Landuyt HW. Novel β-lactamase from Capnocytophaga sp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1501–1504. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roscoe DL, Zemcov SJ, Thornber D, Wise R, Clarke AM. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and β-lactamase characterization of Capnocytophaga species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2197–2200. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.10.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jolivet-Gougeon A, Buffet A, Dupuy C, Sixou JL, Bonnaure-Mallet M, David S, Cormier M. In vitro susceptibilities of Capnocytophaga to β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3186–3188. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.11.3186-3188.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.