Abstract

Methanobactins (Mbns) are ribosomally-produced, post-translationally modified peptidic copper-binding natural products produced under conditions of copper limitation. Genes encoding Mbn biosynthetic and transport proteins have been identified in a wide variety of bacteria, indicating a broader role for Mbns in bacterial metal homeostasis. Many of the genes in the Mbn operons have been assigned functions, but two genes usually present, mbnP and mbnH, encode uncharacterized proteins predicted to reside in the periplasm. MbnH belongs to the bacterial diheme cytochrome c peroxidase (bCcP)/MauG protein family, and MbnP contains no domains of known function. Here, we performed a detailed bioinformatic analysis of both proteins and have biochemically characterized MbnH from Methylosinus (Ms.) trichosporium OB3b. We note that the mbnH and mbnP genes typically co-occur and are located proximal to genes associated with microbial copper homeostasis. Our bioinformatics analysis also revealed that the bCcP/MauG family is significantly more diverse than originally appreciated, and that MbnH is most closely related to the MauG subfamily. A 2.6 Å resolution structure of Ms. trichosporium OB3b MbnH combined with spectroscopic data and peroxidase activity assays provided evidence that MbnH indeed more closely resembles MauG than bCcPs, although its redox properties are significantly different from those of MauG. The overall similarity of MbnH to MauG suggests that MbnH could post-translationally modify a macromolecule, such as internalized CuMbn or its uncharacterized partner protein, MbnP. Our results indicate that MbnH is a MauG-like diheme protein that is likely involved in microbial copper homeostasis and represents a new family within the bCcP/MauG superfamily.

Keywords: metalloprotein, bioinformatics, metal homeostasis, heme, crystal structure, diheme cytochrome c peroxidase, MauG, MbnH, methanobactin

Introduction

Natural products that sequester and import vital and toxic metal ions play important roles in maintaining metal homeostasis in many species. Most well-studied are bacterial small molecules that bind ferric iron and are known as siderophores (iron “carriers”) (1). In recent years, similar molecules that bind other metals have been discovered and characterized (2). One of these is a family of copper-binding compounds called methanobactins (Mbn)5 (3, 4), which are produced from ribosomally synthesized peptides. All Mbns contain post-translational modifications that include nitrogen-containing heterocycles (oxazolones and pyrazinedione/diols) and neighboring thioamide/enethiol groups, and many have other less widespread modifications including “N-terminal” carbonyl groups (5, 6), intramolecular disulfide bonds (3, 6), and sulfonated threonines (7, 8). Of these functional groups, the N-heterocycles and thioamides provide ligands that chelate a copper ion. Mbns bind both CuI and CuII with high affinity (binding constants of 1019–21 m−1 for CuI and 1011–14 m−1 for CuII) (7–9); upon binding, the latter is quickly reduced to CuI via an unknown mechanism.

Under copper-limited conditions, some methanotrophs, bacteria that metabolize methane under aerobic conditions, produce and secrete Mbn (3, 10, 11) to acquire copper for their primary metabolic enzyme, particulate methane monooxygenase (12). Copper-bound Mbn (CuMbn) is then re-internalized by an active transport process that requires a TonB-dependent transporter, MbnT, and may also involve at least one periplasmic binding protein (13–15). The mechanism by which copper is released from Mbn is not yet understood, but has recently been suggested to involve conformational changes that make the bound CuI more accessible (9). Oxidation of CuI to the lower affinity CuII, analogous to FeIII reduction to FeII during iron removal from some siderophores, has also been proposed as a means of copper liberation from CuMbn (9, 16). Given the high affinity of Mbn for copper, the release mechanism is likely to be complex.

The operons responsible for Mbn biosynthesis, transport, and regulation have been identified (17), and their component genes are significantly down-regulated under copper-replete conditions (18). Many of the Mbn operon genes have been assigned functions on the basis of genetic, bioinformatic, and biochemical studies (14, 15, 18–20). Two genes that are present in most Mbn operons but that remain unassigned are mbnP and mbnH (17). The respective proteins, MbnP and MbnH, referred to in the TIGRFAM database as the “metallo-mystery pair” (7), were originally identified as putative periplasmic proteins in Myxococcus xanthus (21), and later as members of the Ms. trichosporium OB3b and Azospirillum sp. B510 Mbn operons (7). MbnH is a member of the bacterial diheme cytochrome c peroxidase (bCcP)/MauG family (PF03150) and more specifically the AZL_007930/MXAN_0977 subfamily (TIGR04039). Members of the bCcP subfamily consist of periplasmic homodimeric enzymes that detoxify H2O2 by reducing it to H2O using a pair of high- and low-spin heme cofactors (22). By contrast, the periplasmic MauG enzyme utilizes its dual heme groups, also consisting of one high-spin and one low-spin heme, to generate a highly reactive bis-FeIV catalytic intermediate, which is used to oxidize two tryptophans to form a tryptophan tryptophylquinone cofactor in the methylamine dehydrogenase (MADH) precursor protein (preMADH) (23). MbnP has been assigned its own family (TIGR04052) and contains no previously identified domains.

MbnPH pairs are encoded in four of five families of Mbn operons, and the tight association between mbnPH and Mbn operons has remained evident as more operons have been identified (4). The mbnP and mbnH genes are also coregulated with mbnT genes in response to copper, both within Mbn operons and in other genomic contexts (15, 18, 24). Given this apparent association with CuMbn uptake and the lack of other conserved candidate genes in the Mbn operon, these two proteins have been suggested to play a role in copper release from Mbn (16). To begin investigating this hypothesis, we have performed comprehensive bioinformatic analysis of both proteins and have biochemically, structurally, and spectroscopically characterized MbnH from Ms. trichosporium OB3b. Our data do not support a bCcP-like peroxidase role for MbnH, but are potentially consistent with the hypothesized roles for MbnH and MbnP in copper-related processes, including copper release from CuMbn.

Results and discussion

Bioinformatic analysis of the bCcP/MauG diheme cytochrome c oxidase family

MbnH belongs to the bCcP/MauG family (PF03150). Although most members of the PF03150 family are annotated as bCcPs or MauGs, bioinformatics analysis indicates that this family is considerably more diverse than both early studies (25) and more recent analyses suggest (26). Construction of an SSN with a stringent cutoff of 1e-90 (Fig. 1, Fig. S1 and File S1) encompassing all members of the PF03150 family in the UniProt database allowed us to analyze this larger family and to identify how MbnH proteins fit into this broader context. The bCcPs and MauGs form clusters that are clearly separate from other diheme enzymes. There are two distinct MauG clusters encompassing the canonical Paracoccus denitrificans (27) and Methylobacterium (28) enzymes, respectively; reflecting this difference, the TIGRFAM MauG family (TIGR03791/IPR022394) detects only the Methylobacterium enzymes. Both clusters include many homologs that are not encoded by genes in mau operons. The bCcPs form a third distinct group, including the well-studied enzymes from P. denitrificans (29), Nitrosomonas europaea (29), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (30, 31).

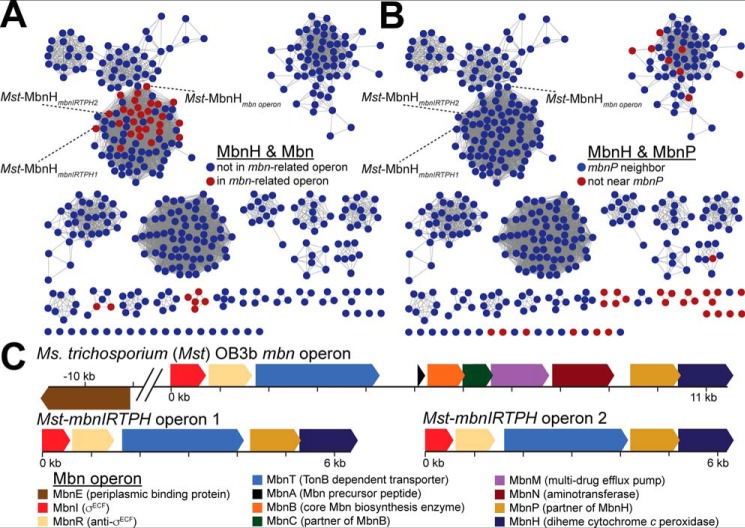

Figure 1.

Sequence similarity network for MbnH. An E-value of 1e-125 was used as a cutoff for edge generation, and sequences with 100% identity were clustered into single nodes. A, a subset of mbnH genes are located in mbn-related operons including MettrDRAFT_3427 in Ms. trichosporium OB3b, the focus of this paper (labeled Mst-MbnHmbn operon). Two additional copper-repressed operons encoding only Mbn import and regulatory machinery (mbnIRTPH) are also present in this species and are labeled Mst-MbnHmbnIRTPH1 and Mst-MbnHmbnIRTPH2. B, most mbnH genes are not in mbn operons, but most are within two genes of an mbnP homolog. C, the copper-repressed Ms. trichosporium OB3b mbn operon that encodes an mbnPH pair. The two additional copper-repressed mbnIRTPH operons encoding only Mbn import and regulatory machinery are also pictured.

Most members of the PF03150 superfamily, including MbnH, do not belong to these two families. MbnH forms a distinct subgroup, but analysis at different E-value cutoffs indicates it is most closely related to the MauG subfamily when compared with other protein groups within the bCcP/MauG superfamily. Several additional clusters are identifiable, including clusters associated with YhjA, the TIGR03981 enzymes, homologs of SPOA0271, and the recently discovered BthA (26) (Fig. S1). Perhaps most relevant to the association of MbnH with Mbn operons, the CorB subfamily includes CorBs from Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z and Methylomicrobium album BG8 as well as MCA2590 from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). This distinct and divergent group encompasses MauG-like diheme enzymes that post-translationally modify a target tryptophan into a kynurenine on a partner protein (CorA or MopE), producing an unusual high-affinity copper-binding site (32, 33). Both the diheme enzyme and its target protein are repressed under copper-replete conditions, and the post-translationally modified CorA and MopE are proposed to play a role in copper acquisition (34, 35). The SPOA0271 system similarly involves post-translational modification of tryptophans in a copper-binding partner protein. Of the 9 identifiable families in the bCcP/MauG superfamily, there are thus at least four families (CorB, Mex-MauG, Pde-MauG, and SPOA0271) involved in tryptophan modification and three (CorB, MbnH, and SPOA0271) with known connections to copper binding or regulation.

Bioinformatic analysis of MbnH

Comparison of MbnH sequences to sequences from other PF03150 subfamilies yields important information (Fig. S2 and File S3). Two heme-binding CXXCH motifs are observed, and a conserved tyrosine is predicted to act as the axial ligand for the second heme, consistent with the coordination sites of MauG. All residues involved in calcium coordination are conserved, as is a tryptophan predicted to mediate interheme electron transfer. A predicted signal peptide identified by SignalP (36) suggests that consistent with other superfamily members, MbnHs are secreted to the periplasm.

The association between Mbn production and mbnH genes is clear but not reciprocal: most mbn operons contain mbnH genes, but most mbnH genes are not located within Mbn operons (Fig. 1A). However, an analysis of genomic neighborhoods (Figs. S2, S4, and S5) in the trimmed datasets of mbnH and mbnP genes supports a high rate of co-occurrence between mbnP and mbnH. 93.11% of mbnP genes are within two genes of mbnH, and 92.06% of mbnH genes are within two genes of mbnP (Fig. 1B). MbnPH pairs are predominantly encoded in proteobacterial genomes, but a subset are intriguingly found in cyanobacteria and spirochaetes, phyla that are not currently known to produce Mbns (Fig. S5). Although mbnP genes (annotated as members of the TIGR04052 family) are described as having a conserved four-cysteine motif, investigation of sequence conservation among MbnP family members indicates that these uncharacterized proteins are better described as periplasmic proteins with six highly conserved cysteines and two highly conserved histidines. Notably, this pattern of residue conservation is compatible with a role in metal (and specifically copper) binding. MbnP proteins also have a highly conserved WXW motif (Fig. S6).

The mbnPH pairs are frequently associated with outer membrane importers: over 22.66% are adjacent to genes encoding TonB-dependent transporters (37), and another 15.18% are near genes encoding β-barrel outer membrane importers of hydrophobic compounds (38), variously described as members of the poorly characterized COG4313 (38–40) or PF13557/“phenol-MetA degradation pathway” families (Fig. S4B). Other transporter families are also represented, including other outer membrane β-barrel proteins, and widespread but poorly annotated members of the porin superfamily, estimated at ∼36% abundance after manual examination of a quarter of mbnH genome neighborhoods. However, the association with copper-exporting P-type ATPases noted in the TIGRFAM description does not appear to be a major feature of the broader family.

An association with copper is also apparent (Fig. 1C and Fig. S4A). Copper-responsive gene regulation has been observed previously for both the mbn operon and nonoperon mbnPH pairs in Ms. trichosporium OB3b (15, 18). Mbns in other species are also predicted to constitute chalkophores involved in copper uptake, and so it is notable that there are several sets of neighboring genes connected to copper homeostasis and cuproenzyme assembly. Beyond the 6.54% of mbnPH pairs that are in Mbn operons, 4.44% are near copC(D) genes encoding a putative inner membrane copper uptake system and 16.36% are near genes encoding DUF461/PCuAC proteins, which are putative periplasmic copper chaperones (41–43).

Biochemical and structural characterization of MbnH

Heterologous expression of MbnH from Ms. trichosporium OB3b in Escherichia coli resulted in soluble protein that was readily purified (Fig. S7). Size exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering-quasi elastic light scattering (SEC-MALS-QELS) analysis of purified MbnH revealed that the protein exists as a monomer in solution (Fig. S8). MbnH was co-expressed with cytochrome c maturation (ccm) proteins to improve loading of its c-type heme cofactors (44) under aerobic conditions. The electronic absorption spectrum of as-isolated MbnH exhibits a peak at 404 nm, which is consistent with the presence of ferric (FeIII) heme (Fig. 2A).

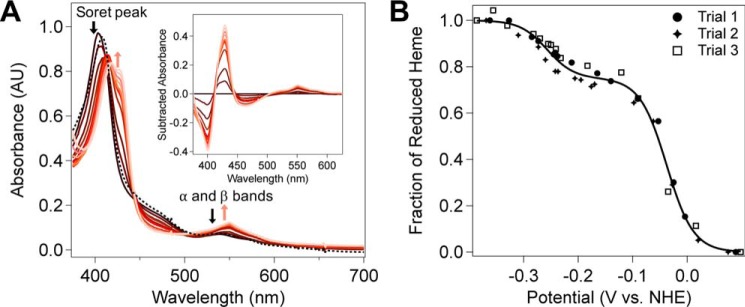

Figure 2.

Redox titration of Ms. trichosporium OB3b MbnH. A, absorption spectra of ∼9 μm MbnH (black) in 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, and ∼9 μm FMN as the hemes are converted to the reduced form (pink) by the addition of sodium dithionite. Full reoxidation of reduced heme (black, dashed line) was accomplished by exposure to air. Inset shows the difference spectra. B, the Em values for each heme were determined by plotting the fraction of reduced heme against the potential. The fraction of reduced heme was determined by tracking the spectral changes at 550 nm. The data from three distinct experiments (illustrated with filled circles, filled crosses, and open squares) are overlaid and were included in the fit analysis. The solid line represents the best fit using Equation 1, which describes a species with two redox active components. From the fit, the midpoint potential for the first species is −38 ± 2 mV and the midpoint potential for the second species is −257 ± 5 mV. The fit value for the number of electrons (n) was 1.04 ± 0.0788, and the fraction of reduced heme attributed to the first redox active center, a (Equation 1), was 0.749 ± 0.0126. The potential was measured against Ag/AgCl and converted to NHE by the addition of 198 mV.

A single crystal of MbnH was obtained, and the structure was determined to 2.6 Å resolution with phasing information provided by the iron anomalous signal at 1.722003 Å (Table 1). There are two molecules of MbnH (chains A and B) per asymmetric unit, and the final model consists of residues 25–374 for chain A and 25–374 for chain B (although residues 147–171 of chain B could not be modeled) (Fig. 3A). The two molecules can be superimposed with a root mean square deviation of 0.354 Å. Several interchain hydrogen bonds involving residues Glu-A219, His-A225, Glu-B314, Arg-B329, and Asp-B342 are present in the asymmetric unit, but the interface is minimal, consistent with the monomeric state of MbnH in solution. The two MbnH molecules are also linked by a non-iron atom that remains unmodeled (Fig. S9). The overall-fold resembles that of other bCcP/MauG superfamily members, including MauG. Superposition of MbnH molecule A with MauG from the P. denitrificans MauG/preMADH complex (45) yields a root mean square deviation of 2.44 Å over 284 Cα atoms, with differences confined largely to flexible loop regions (Fig. S9). However, unlike Pde-MauG, which has only been crystallized in the presence of preMADH, the MbnH structure has been obtained in the absence of a substrate.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics for MbnH

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.722003 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.6 (2.69–2.60) |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 71.56, 85.76, 133.6 |

| α, β, γ | 90°, 90°, 90° |

| Completeness | 99.1 (99.3) |

| I/σI | 21.15 (4.75) |

| Linear R-factor | 0.148 (0.846) |

| Square R-factor | 0.137 (0.925) |

| Rmeas | 0.152 (0.871) |

| Rpim | 0.035 (0.202) |

| R/Rfree | 0.233/0.297 |

| Rfree test set | 2000 reflections (8.05%) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 26.1 |

| Fo, Fc correlation | 0.89 |

| Number of atoms | 5457 |

| Average B, all (Å2) | 27 |

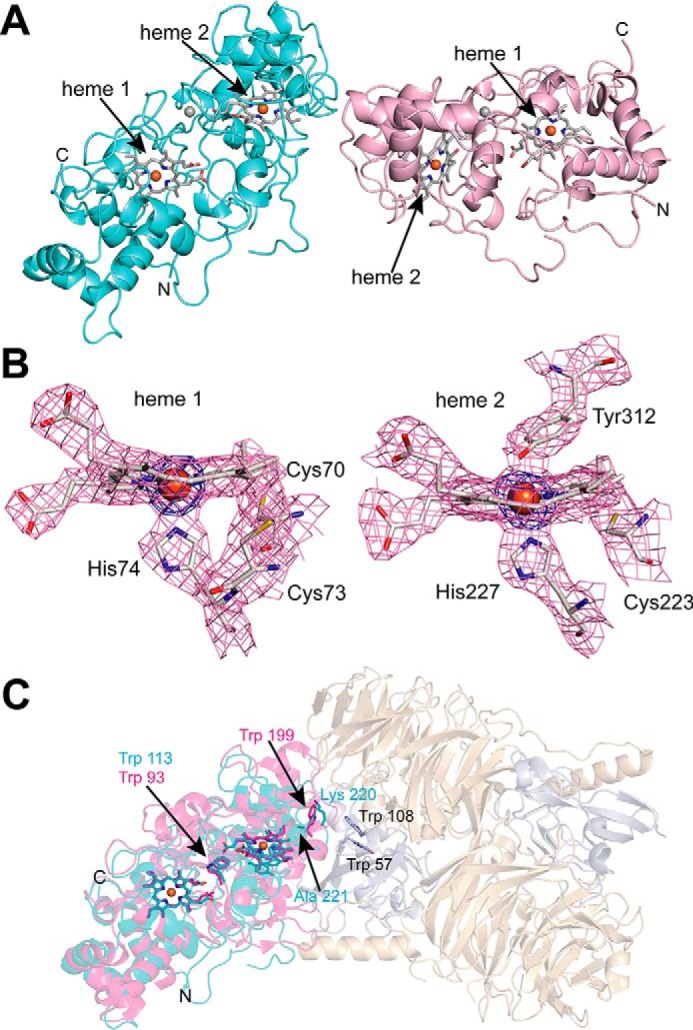

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of Ms. trichosporium OB3b MbnH. A, cartoon depiction of the two MbnH molecules in asymmetric unit with heme groups shown as sticks and Ca2+ ions as spheres (gray). B, heme groups and coordinating protein ligands along with associated electron density maps (2Fo − Fc, pink, contoured at 1.2 σ; iron anomalous, blue, contoured at 6σ) in chain A of MbnH. C, superposition of MbnH chain A (cyan) and chain A (magenta) of the P. denitrificans MauG/preMADH complex (PDB code 3L4M, preMADH subunits shown in wheat and gray). Key residues discussed in the text are shown as sticks.

Each monomer houses two c-type heme groups (heme 1 and heme 2, Fig. 3B) and an atom modeled as Ca2+ (Fig. 3A, gray spheres) that is positioned approximately midway between the heme groups. A conserved tyrosine residue, Tyr-312 (Fig. S3), serves as an axial ligand to the six-coordinate heme (heme 2, Fig. 3B). This tyrosine is conserved in all members of the superfamily known to perform post-translational modifications; the two large families that are predicted to consist of peroxidases instead contain a methionine ligand (46). This methionine elevates the redox potential of the six-coordinate heme compared with the five-coordinate heme, permitting the formation of a mixed-valent active state capable of effecting electron transfer. The axial tyrosine ligand in MbnH is also observed in the low-spin, six-coordinate heme of MauG (45), in which it permits stabilization of a bis-FeIV intermediate that is used to oxidize tryptophan residues in the substrate protein, preMADH (23, 47). A conserved tryptophan, Trp-113, lies between the two hemes; this residue has been proposed to mediate electron transfer in other superfamily members (48–53) (Fig. 3C), barring the recently-discovered BthA subfamily (26) (Fig. S1).

Interestingly, in the superposition of MbnH molecule A with the MauG/preMADH complex, MbnH molecule B is positioned roughly at the location of the preMADH protein (Fig. 3C). This observation, combined with the relative disorder of molecule B (25 more residues are missing from the final model of chain B), may indicate that MbnH interacts with another protein such as MbnP or even a large ligand such as CuMbn using this surface. In the P. denitrificans MauG/preMADH complex, a tryptophan residue from MauG (Trp-199, Pde-MauG numbering), located between heme 2 and the preMADH modification site, is proposed to facilitate electron transfer to the modification site (Trp-57 and Trp-108 in preMADH) (Fig. 3C), although this residue is not conserved in any bCcP/MauG families beyond the subset of Paracoccus MauG homologs found within authentic mau operons (Fig. S2) (51, 54). The structurally equivalent position in MbnH is occupied by residues Lys-220 and Ala-221 (Fig. 3C, Fig. S10), and there are no tryptophan residues, conserved or nonconserved, in the vicinity. Residue Tyr-198, which is located near the putative interaction surface, is ∼20 Å away from heme 2, but could form an electron transfer pathway to heme 2 via Tyr-195 and Tyr-216 (Fig. S11). All three of these tyrosine residues are highly, although not universally, conserved in MbnH proteins. Notably, Methylobacterium extorquens MauG and its homologs have a highly conserved tryptophan residue at the position of Tyr-198 (Fig. S3).

Spectroscopic characterization of MbnH

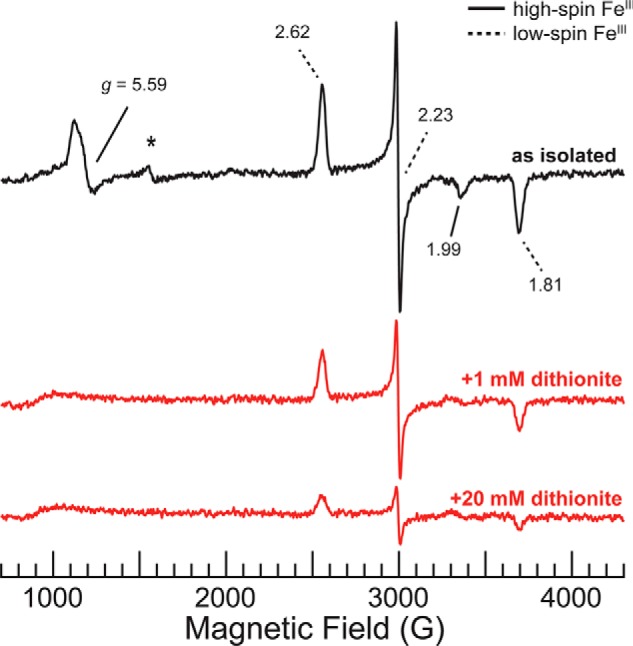

The two heme groups in MbnH were further characterized by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. We identified one high-spin FeIII heme with axial g-tensor (g⊥ = 5.59, g‖ = 1.99) and one low-spin FeIII heme (g1 = 2.62, g2 = 2.23, g3 = 1.81) (Fig. 4). The MbnH EPR spectrum is markedly different from those of bacterial diheme peroxidases, which all exhibit characteristic signals of the highly-anisotropic low-spin (HALS) FeIII (g1 ∼ 3.4, g2 ∼ 2.0, g3 ∼ 0.6) type (22, 55–58). An EPR signal attributable to highly-anisotropic low-spin FeIII was not observed for MbnH even when conducting the EPR measurements at ∼4 K (Fig. S12), where such signals are best detected. Instead, the MbnH EPR spectrum bears a striking resemblance to that of MauG. The MauG spectrum exhibits signals from one high-spin FeIII heme (g⊥ = 5.57, g‖ = 1.99; attributed to the five-coordinate heme with an axial His ligand), and one low-spin FeIII heme (g1 = 2.54, g2 = 2.19, g3 = 1.87; attributed to the six-coordinate heme with His and Tyr axial ligands) (58, 59). Given the nearly identical g-values of the two hemes in MbnH and MauG, we also assign the high-spin FeIII resonance to the five-coordinate heme (heme 1) and the low-spin FeIII resonance to the six-coordinate heme (heme 2).

Figure 4.

X-band continuous wave (CW) EPR spectra of 190 μm as isolated MbnH (black) and MbnH reduced with 1 mm or 20 mm dithionite (red). Solid black lines indicate g-values assigned to heme 1, and dotted black lines indicate g-values assigned to heme 2. Asterisk denotes resonance attributable to a small amount of high-spin “junk” FeIII, g = 4.3. Conditions used were: 9.364–9.365 GHz microwave frequency, 80 ms time constant, 12.5 G modulation amplitude, 120 s scan time, temperature 20 K, and 10 scans per spectrum.

Like MauG, but unlike bCcPs (23), ascorbate does not reduce either heme of MbnH, as shown by the identical electronic absorption spectra before and after treatment (Fig. S13). However, addition of 1 eq (∼9 μm) of sodium dithionite to the isolated MbnH initially results in a red shift of the Soret peak to ∼415 nm with a small shoulder at 430 nm (Fig. 2A), consistent with partial reduction of FeIII heme to the FeII state (27). Upon the addition of excess sodium dithionite (1 mm), the absorption spectrum exhibited a further bathochromic shift and formation of a more pronounced shoulder at 430 nm (Fig. 2A), consistent with further reduction of FeIII heme to the FeII state.

Interestingly, the UV-visible spectrum of the partially-reduced MbnH is nearly identical to those of the Pde-MauG T67A and E113Q variants with ≥1 e− equivalent of dithionite, but not that of WT Pde-MauG with any amount of dithionite (60, 61). Partial reduction of WT Pde-MauG with dithionite results in an equilibrium of mixed valence FeII–FeIII and FeIII–FeII states due to redox cooperativity between the two heme cofactors (59, 62, 63). Addition of excess dithionite results in a fully reduced FeII–FeII state. In contrast, treatment of T67A Pde-MauG with ≥1 e− eq of dithionite results in a mixed-valent, localized low spin heme FeIII, high spin heme FeII state (61).

A comparison of the distal pocket in MbnH to that in Pde-MauG reveals one notable difference in heme environment: Pde-MauG residue Thr-67 is replaced by an alanine in MbnH. In Pde-MauG, Thr-67 has been implicated in the overall stability of the protein and in modulating the redox cooperativity between the two heme cofactors (60, 61, 63, 64). This residue is proposed to help maintain a hydrophobic environment in the proximal pocket and restrict the movement of the high-spin heme.

EPR was used to evaluate whether the presence of alanine in MbnH leads to similar reduction behavior to that observed in the T67A Pde-MauG mutant. The EPR spectrum of 190 μm MbnH reduced with 1 mm dithionite shows complete reduction of heme 1 to the EPR-silent FeII state, whereas the heme 2 signal remains prominent with unaltered g-values (Fig. 4). We estimate that this dithionite treatment thus converted ∼50% of the FeIII–FeIII form to a mixed-valent, localized FeII-heme 1/FeIII-heme 2 state, suggesting that complete reduction of the second heme would be possible. Indeed, addition of 20 mm dithionite fully reduced heme 1 and reduced ∼80% of the heme 2 EPR signal (Fig. 4).

We then monitored the change in absorbance at 550 nm during dithionite addition to determine the midpoint potentials of MbnH. Initial attempts to fit the data using the Nernst equation yielded poor fits (Fig. S14), but a better fit was obtained using a modified Nernst equation that describes the behavior of a system containing two redox active components. This fit revealed an average midpoint reduction potential of −38 ± 2 mV versus NHE at pH 7.5 (Fig. 2B and Fig. S15), which is notably higher than the Em1 reported for MauG (-159 ± 10 mV versus NHE) (63). The second midpoint potential, Em2, was determined to be −257 ± 5 mV versus NHE, which is more similar to the reported Em2 for MauG (−244 ± 5 mV versus NHE).

The biphasic reduction behavior exhibited in Fig. 2B can be interpreted in terms of a roughly statistical distribution of heme incorporation into heme sites 1 and 2 (i.e. four equally populated MbnH populations: A (apo), B (heme 1 loaded, heme 2 apo), C (heme 1 apo, heme 2 loaded), and D (both hemes loaded)) with redox cooperativity exhibited between the heme sites, as seen in MauG. In such a scenario, the high reduction potential phase, which accounts for the majority of the total MbnH heme reduction, is attributable to reduction of the fully diheme-loaded (exhibiting redox cooperativity) and exclusively heme 1-loaded MbnH (because the high spin heme will exhibit a higher reduction potential), namely populations B+D. This higher reduction potential phase accounts for roughly triple the total MbnH heme reduction as that seen for the low potential phase, population D, exactly as one would expect for this low potential phase being attributable to exclusively heme 2-loaded MbnH in the aforementioned statistical distribution.

MbnH activity assays

MbnH was investigated for general peroxidase and cytochrome c-specific activities. Using H2O2 as the oxidant and the dye o-dianisidine as the electron donor, the absorbance maximum for the oxidized dye at 460 nm was monitored for 1800 s after addition of MbnH (horseradish peroxidase was used as a positive control). Although reaction of MbnH was slow, an increase at 460 nm suggests that MbnH, like horseradish peroxidase, exhibits general peroxidase activity (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Electronic absorption spectra monitoring the peroxidase activity of MbnH. A, reaction of 20 nm MbnH with 100 μm o-dianisidine and 1 mm H2O2 reveals gradual oxidation of the dye, as indicated by the rise in absorbance at 460 nm. B, the same reaction as in A performed with 0.3 nm horseradish peroxidase rather than MbnH also reveals oxidation of o-dianisidine. C, reaction of 50 nm MbnH with 5 μm reduced horse heart cytochrome c and 1 mm H2O2 shows no change to the absorption peak of α-band the ferrocytochrome c at 550 nm and indicates no oxidation of horse heart cytochrome c.

However, activity tests of MbnH using reduced horse heart cytochrome c as the electron donor produced no change in the optical spectrum of ferrocytochrome c, indicating that MbnH does not exhibit cytochrome c-specific activity (Fig. 5C). By contrast, P. denitrificans cytochrome c peroxidase catalyzes the oxidation of horse heart ferrocytochrome c at a rate of 62,000 min−1 (29). The behavior of MbnH is consistent with what has been reported for MauG (27) and suggests that MbnH is not a typical cytochrome c peroxidase, functioning to detoxify H2O2. Interestingly, upon reaction with H2O2, MbnH does develop a nIR peak at 960 nm within seconds, as observed for both Pde-MauG (23, 60, 64) and BthA (26) (Fig. S16). This feature has been attributed to a charge resonance stabilization involving both hemes and the intervening tryptophan residue.

Conclusions

The bioinformatics, structural, spectroscopic, and activity data presented here indicate that MbnH is a MauG-like diheme protein that represents a new family in the increasingly diverse bCcP/MauG diheme cytochrome c peroxidase superfamily. The MbnH family is distinct in both sequence and genomic context from the other 8 identified families (Fig. S1). MbnH additionally exhibits redox properties that are distinct from bCcPs, Pde-MauG, and Bth-BthA. It has a more positive reduction potential, it is not reduced by ascorbate, it can form a mixed valent state upon partial reduction, and both hemes can ultimately be reduced to the FeII state. MbnH is likely not a peroxidase and instead may catalyze modification of a yet-to-be-identified substrate. As proposed previously, MbnH might modify CuMbn to facilitate copper release. Another intriguing possibility is that the uncharacterized partner protein, MbnP, may be the substrate that is post-translationally modified by MbnH. This pair might resemble the CorA/MopE system, in which the MauG-like enzyme CorB modifies a conserved tryptophan in CorA/MopE to form the high-affinity copper ligand kynurenine (32, 65). By analogy, one or more modified tryptophans in MbnP could bind copper and perhaps play a role in copper release from CuMbn. In support of this model, there are two very highly conserved tryptophan residues in MbnPs, Trp-174 and Trp-176 in the Ms. trichosporium OB3b MbnP found in the mbn operon (Fig. S5). Strikingly, this WXW motif is only absent in mbnP genes that are not located next to mbnH genes, whereas conservation of the similarly highly conserved cysteine and histidine motifs is not correlated with the presence of adjacent mbnH genes (Fig. S5, A–C). Future studies will focus on addressing this hypothesis. Regardless, the characterization of MbnH as a MauG-like enzyme adds a new subclass to the large and diverse bCcP/MauG family and constitutes an important step toward resolving the roles of the “metallo-mystery pair (7).”

Experimental procedures

Bioinformatics

The PF03150 sequence similarity network (SSN) was constructed on February 26, 2019 as described previously (15), using the EFI-EST (66, 67) web interface and allowing analysis of all proteins in the UniProt database (2019-01) and the InterPro database (72) annotated as PF03150 family members. Metadata were obtained for all 16,517 input sequences (File S2). An E-value cutoff of 1e-90 was used for edges in the final SSN, and sequences with greater than 95% identity were clustered into single nodes, resulting in a network with 10,883 nodes (Files S1–S3). Nodes were preliminarily identified as members of a given family on the basis of their annotation (subfamily-specific InterPro or TIGRFAM membership or SwissProt annotation) and on the basis of experimental evidence; this information was added to the metadata file and incorporated into the SSN for visualization. Unique annotations included IPR01538 (DHOR) and IPR023893 (TIGR03981). Genome neighborhoods for members of the MauG and CorB families were investigated further, using the EFI-GNT webtool (67, 68) to identify bCcP/MauG superfamily members with genomic neighborhoods consistent with their putative roles (66, 67). These were further used to confirm the identities of members of the BthAB, CorB, Mex-MauG, Pde-MauG, MbnH, SPOA0271, and TIGR03981 subfamilies. (YhjA and bCcP family members do not have broadly conserved genomic neighbors.) To analyze sequence conservation, protein sequences belonging to representative nodes from all 9 identified clusters were used to generate cluster-specific Hidden Markov models (HMMs) using hmmbuild, and all cluster sequences were then aligned against those cluster-specific models. Consensus logos were assembled from positions present in the models. Core genomic neighborhoods for those 9 clusters were also identified using the EFI-GNT webtool.

To investigate MbnH, protein sequences from all genes annotated as members of the TIGR04039 family were downloaded from the JGI/IMG database (69) on 2019.06.19 along with metadata (File S2). 954 initial sequences were trimmed on the basis of length (sequences >470 or <330 amino acids were not used) or lack of a complete genomic neighborhood (±5 genes upstream and downstream of mbnH). An SSN was generated for the trimmed MbnH sequences using the EFI/EST web interface (66). Sequences with 100% identity were clustered into single nodes, decreasing overrepresented sequences, particularly those from Leptospira isolates, and a cutoff E-value of 1e-125 was used for edge construction (File S3), yielding a network with 428 representative nodes. Clustering patterns did not differ using 95 or 90% cutoffs for representative node choice. Additional information (such as proximity to MbnP) was added to the metadata file for visualization in the sequence similarity network. Sequences from EFI nodes were aligned against the TIGR04039 HMM using hmmalign (70, 71). Hierarchical clustering of mbnH genes (from representative EFI-generated nodes) and their genomic neighborhood was performed as described previously (72). Traits analyzed included TIGRFAM or PFAM families found within 5 genes in either direction of >2.5% of mbnH genes.

Initial construction and analysis of sequence similarity networks for MbnP proceeded in the same way as described for MbnH, including download of 973 initial protein sequences, collection of metadata (File S2), and construction of a sequence similarity network (File S4), except that the TIGR04052 family was used to identify MbnP homologs, length cutoffs were used to remove sequences with fewer than 245 or greater than 380 residues, and a less stringent E-value cutoff (1e-60) was used, yielding a network with 455 representative nodes. As with MbnH, clustering patterns did not differ using 95 or 90% cutoffs for representative node choice, and truncated sequences (210 amino acids or less) or fused proteins (>400 amino acids) were removed. Sequences from EFI nodes were originally aligned against the TIGR04052 HMM using hmmalign, but some areas with high conservation were not part of that model. To generate an improved HMM, a trimmed input file of EFI-EST–generated representative nodes at 40% identity was aligned using MAFFT (in L-INS-I mode) (72). This alignment was used to construct a new HMM via hmmbuild, and hmmalign was used to align the sequence database against this improved model to generate a sequence logo and calculate the conservation of specific residues of interest (File S5). Information regarding the conservation of specific residues (and the presence of mbnH within two genes of mbnP) was added to the SSN metadata and visualized. 60 sequences from the trimmed MAFFT alignment were extracted using HHfilter and used to generate predicted topology for the MbnP family, using Ali2D (73, 74).

Protein expression and purification

To heterologously overexpress MbnH, the gene from Ms. trichosporium OB3b was initially cloned into a pSGC vector containing an N-terminal hexa-histidine (His6) affinity tag. However, soluble expression was only obtained by cloning the codon-optimized mbnH gene (MettrDRAFT_3427) into the MCS-2 site of a pCDFDuet-1 vector, retaining the native signal peptide and adding a C-terminal strep tag. The neighboring mbnP gene (MettrDRAFT_3426) was also codon-optimized and inserted into MCS-1. We did not obtain soluble MbnP from this construct, but MbnH exhibited increased stability, so all data reported herein were obtained from this construct. To improve incorporation of c-type hemes in MbnH during aerobic expression, the modified pCDFDuet-1 vector was cotransformed with a pEC86 vector (containing the cytochrome c maturation or ccm genes) (44) into BL21 (DE3) cells. Transformants were initially cultured in LB media at 37 °C supplemented with 70 μg/ml of spectinomycin and 34 μg/ml of chloramphenicol, and then transferred to ZYM-5052 autoinduction media (75). At an A600 of 0.7–1, the temperature of the shaking incubator was lowered to 18 °C for 12–18 h to permit protein expression.

Proteins were purified using a combination of affinity, ion exchange, and size-exclusion chromatographies, as described previously (15). Briefly, lysate containing MbnH was loaded onto a Strep-Tactin column (IBA), and protein was eluted by addition of a buffer containing 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm desthiobiotin. Purification by size exclusion chromatography was performed using a Superdex 200 column (XK 16/100, GE Life Sciences), and protein was stored in 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, and 100 mm NaCl at 7.5 °C. We were able to achieve ∼50% overall heme loading in the purified protein as determined by ICP-MS.

SEC-MALS-QELS

SEC-MALS-QELS was performed on purified MbnH to determine its molar mass in solution. An Agilent 1260 series HPLC outfitted with a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Life Sciences) was used for SEC, and a Wyatt DAWN HELEOS II multi-angle static light scattering detector, a Wyatt QELS dynamic light scattering detector, and a Wyatt T-rEx differential refractive index detector were used for MALS-QELS. 50 μl of 188 μm protein stock in 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl buffer was injected onto the column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Protein elution was detected by monitoring the absorbance at 280 nm. Data analysis and molecular weight determination were performed in Astra (Wyatt) 5.3.4, and the chromatograms were plotted using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software).

Spectroscopic sample preparation and data collection

All optical spectra were acquired inside a Coy anaerobic chamber using an Agilent 8453 spectrometer outfitted with a Peltier temperature controller. Samples were prepared anaerobically in degassed buffers containing 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, and 100 mm NaCl. Midpoint reduction potential values of MbnH were determined by potentiometric titrations inside the anaerobic chamber using a solution containing MbnH and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) as a redox mediator. Sodium dithionite was used as the reductant and added in increments directly to the cuvette from 0.5, 1, 10, or 100 mm stock solution. Reductant was added up to a final concentration of 1.6 mm to ensure the titration occurred over the full potential range of each heme. Each time reductant was added to the cuvette, potentials were measured directly in the quartz cuvette using a two-electrode system with a glassy carbon working electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode connected to a multimeter. All potentials were converted to NHE by the addition of 198 mV to the measured potentials. Oxidation of reduced MbnH was achieved by removal of the protein from the anaerobic chamber to oxidize in air over 1 h. This experiment was performed in triplicate, and the fraction of MbnH reduced for each trial was plotted as a function of potential. The midpoint reduction potentials were determined by fitting the combined data set to a modified Nernst equation (Eq. 1) that includes the behavior of a system with two redox active centers. In this equation “a” represents the fraction of the total absorbance change attributable to the first redox active center and “a-1” is the fraction of absorbance change attributed to the second redox active center.

| (Eq. 1) |

Protein samples for EPR spectroscopy were concentrated to 200 μm protein, prepared as described above, and then transferred into a Wilmad quartz X-band EPR tube (Sigma) and frozen in liquid nitrogen within the Coy anaerobic chamber. Samples were stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis. All spectra were acquired on a Bruker ESP-300 X-band spectrometer with a liquid helium flow Oxford Instruments ESR-900 cryostat.

MbnH activity assays

A dye-linked assay utilizing o-dianisidine (Sigma) as an electron donor was performed to probe peroxidase activity of MbnH. A reaction mixture containing 20 nm MbnH (in 0.15 m citric phosphate buffer, pH 5) and 100 μm o-dianisidine was monitored at 460 nm after the addition of 1 mm H2O2. A separate reaction using horseradish peroxidase served as a positive control for oxidation of the dye. Cytochrome c-specific activity was assessed in a reaction of 50 nm MbnH with 5 μm ascorbate-reduced horse heart cytochrome c (Sigma) and 1 mm H2O2, wherein a decrease in the intensity of α-band at 550 nm indicates the oxidation of ferrocytochrome c.

Crystallization and structure determination

One crystal of MbnH was obtained from sparse-matrix screen in a condition that contained 0.05 m BisTris, pH 6.5, 45% (v/v) polypropylene glycol P400 (MCSG III, B6); the crystal was never reproduced despite numerous attempts over many months. This crystal was frozen using the mother liquor containing 20% ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant. Data were acquired at the LS-CAT beamline (21-ID-D) at the Advanced Photon Source, and data reduction was performed using HKL2000 (76). Phases were determined using Phenix AutoSol and iron anomalous data collected at 1.722003 Å, and an initial model was built using Phenix AutoBuild (77). Improvements to the model, as well-as inclusion of the c-type heme groups were performed manually in Coot (77), and the structure was refined with Phenix Refine and REFMAC5 (77, 78). Anomalous difference maps were generated in Phenix GUI (78) and figures were prepared with MacPyMOL (Schrödinger LLC).

Author contributions

G. E. K., L. M. K. D., and A. C. R. conceptualization; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., and S. C. data curation; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., and S. C. formal analysis; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., and M. O. R. validation; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., S. C., and A. C. R. investigation; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., B. M. H., and A. C. R. visualization; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., and M. O. R. methodology; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., B. M. H., and A. C. R. writing-original draft; G. E. K., L. M. K. D., A. C. M., M. O. R., B. M. H., and A. C. R. writing-review and editing; B. M. H. and A. C. R. supervision; B. M. H. and A. C. R. funding acquisition; A. C. R. resources; A. C. R. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a United States Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor Grant 085P1000817.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM118035 (to A. C. R.), GM111097 (to B. M. H.), and F32GM110934 (to L. M. K. D.), and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Enrichment Program grant (to L. M. K. D.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S16 and Files S1–S5.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 6E1C) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- Mbn

- methanobactin

- bCcP

- bacterial diheme cytochrome c peroxidase

- CuMbn

- copper-bound methanobactin

- Ms

- Methylosinus

- preMADH

- methylamine dehydrogenase (MADH) precursor protein

- SEC-MALS-QELS

- size exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering-quasi elastic light scattering

- SSN

- sequence similarity network

- Em

- midpoint potential

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- HMM

- Hidden Markov model.

References

- 1. Wilson B. R., Bogdan A. R., Miyazawa M., Hashimoto K., and Tsuji Y. (2016) Siderophores in iron metabolism: from mechanism to therapy potential. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 1077–1090 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kenney G. E., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2018) Chalkophores. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 645–676 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim H. J., Graham D. W., DiSpirito A. A., Alterman M. A., Galeva N., Larive C. K., Asunskis D., and Sherwood P. M. (2004) Methanobactin, a copper-acquisition compound from methane oxidizing bacteria. Science 305, 1612–1615 10.1126/science.1098322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenney G. E., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2018) Methanobactins: maintaining copper homeostasis in methanotrophs and beyond. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 4606–4615 10.1074/jbc.TM117.000185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behling L. A., Hartsel S. C., Lewis D. E., DiSpirito A. A., Choi D. W., Masterson L. R., Veglia G., and Gallagher W. H. (2008) NMR, mass spectrometry and chemical evidence reveal a different chemical structure for methanobactin that contains oxazolone rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12604–12605 10.1021/ja804747d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kenney G. E., Goering A. W., Ross M. O., DeHart C. J., Thomas P. M., Hoffman B. M., Kelleher N. L., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2016) Characterization of methanobactin from Methylosinus sp. LW4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11124–11127 10.1021/jacs.6b06821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krentz B. D., Mulheron H. J., Semrau J. D., Dispirito A. A., Bandow N. L., Haft D. H., Vuilleumier S., Murrell J. C., McEllistrem M. T., Hartsel S. C., and Gallagher W. H. (2010) A comparison of methanobactins from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b and Methylocystis strain SB2 predicts methanobactins are synthesized from diverse peptide precursors modified to create a common core for binding and reducing copper ions. Biochemistry 49, 10117–10130 10.1021/bi1014375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El Ghazouani A., Baslé A., Gray J., Graham D. W., Firbank S. J., and Dennison C. (2012) Variations in methanobactin structure influences copper utilization by methane-oxidizing bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8400–8404 10.1073/pnas.1112921109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baslé A., El Ghazouani A., Lee J., and Dennison C. (2018) Insight into metal removal from peptides that sequester copper for methane oxidation. Chemistry 24, 4515–4518 10.1002/chem.201706035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiSpirito A. A., Zahn J. A., Graham D. W., Kim H. J., Larive C. K., Derrick T. S., Cox C. D., and Taylor A. (1998) Copper-binding compounds from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3606–3613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Téllez C. M., Gaus K. P., Graham D. W., Arnold R. G., and Guzman R. Z. (1998) Isolation of copper biochelates from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b and soluble methane monooxygenase mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 1115–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sirajuddin S., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2015) Enzymatic oxidation of methane. Biochemistry 54, 2283–2294 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balasubramanian R., Kenney G. E., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2011) Dual pathways for copper uptake by methanotrophic bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37313–37319 10.1074/jbc.M111.284984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gu W., Farhan Ul Haque M., Baral B. S., Turpin E. A., Bandow N. L., Kremmer E., Flatley A., Zischka H., DiSpirito A. A., and Semrau J. D. (2016) A TonB-dependent transporter is responsible for methanobactin uptake by Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 1917–1923 10.1128/AEM.03884-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dassama L. M., Kenney G. E., Ro S. Y., Zielazinski E. L., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2016) Methanobactin transport machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 13027–13032 10.1073/pnas.1603578113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dassama L. M., Kenney G. E., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2017) Methanobactins: from genome to function. Metallomics 9, 7–20 10.1039/C6MT00208K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kenney G. E., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2013) Genome mining for methanobactins. BMC Biol. 11, 17 10.1186/1741-7007-11-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kenney G. E., Sadek M., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2016) Copper-responsive gene expression in the methanotroph Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Metallomics 8, 931–940 10.1039/C5MT00289C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kenney G. E., Dassama L. M. K., Pandelia M. E., Gizzi A. S., Martinie R. J., Gao P., DeHart C. J., Schachner L. F., Skinner O. S., Ro S. Y., Zhu X., Sadek M., Thomas P. M., Almo S. C., Bollinger J. M. Jr., et al. (2018) The biosynthesis of methanobactin. Science 359, 1411–1416 10.1126/science.aap9437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park Y. J., Kenney G. E., Schachner L. F., Kelleher N. L., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2018) Repurposed HisC aminotransferases complete the biosynthesis of some methanobactins. Biochemistry 57, 3515–3523 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhat S., Zhu X., Patel R. P., Orlando R., and Shimkets L. J. (2011) Identification and localization of Myxococcus xanthus porins and lipoproteins. PLoS ONE 6, e27475 10.1371/journal.pone.0027475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fülöp V., Watmough N. J., and Ferguson S. J. (2000) Structure and enzymology of two bacterial diheme enzymes: cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase and cytochrome c peroxidase. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 51, 163–204 10.1016/S0898-8838(00)51003-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geng J., Davis I., Liu F., and Liu A. (2014) Bis-Fe(IV): nature's sniper for long-range oxidation. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 19, 1057–1067 10.1007/s00775-014-1123-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gu W., and Semrau J. D. (2017) Copper and cerium-regulated gene expression in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 8499–8516 10.1007/s00253-017-8572-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atack J. M., and Kelly D. J. (2007) Structure, mechanism and physiological roles of bacterial cytochrome c peroxidases. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 52, 73–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rizzolo K., Cohen S. E., Weitz A. C., López Muñoz M. M., Hendrich M. P., Drennan C. L., and Elliott S. J. (2019) A widely distributed diheme enzyme from Burkholderia that displays an atypically stable bis-Fe(IV) state. Nat. Commun. 10, 1101 10.1038/s41467-019-09020-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y., Graichen M. E., Liu A., Pearson A. R., Wilmot C. M., and Davidson V. L. (2003) MauG, a novel diheme protein required for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis. Biochemistry 42, 7318–7325 10.1021/bi034243q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chistoserdov A. Y., Chistoserdova L. V., McIntire W. S., and Lidstrom M. E. (1994) Genetic organization of the mau gene cluster in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: complete nucleotide sequence and generation and characteristics of mau mutants. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4052–4065 10.1128/jb.176.13.4052-4065.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilmour R., Goodhew C. F., Pettigrew G. W., Prazeres S., Moura I., and Moura J. J. (1993) Spectroscopic characterization of cytochrome c peroxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochem. J. 294, 745–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rönnberg M., and Ellfolk N. (1979) Heme-linked properties of Pseudomonas cytochrome c peroxidase: evidence for non-equivalence of the hemes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 581, 325–333 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90252-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellfolk N., Rönnberg M., Aasa R., Andréasson L. E., and Vänngård T. (1983) Properties and function of the two hemes in Pseudomonas cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 743, 23–30 10.1016/0167-4838(83)90413-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Helland R., Fjellbirkeland A., Karlsen O. A., Ve T., Lillehaug J. R., and Jensen H. B. (2008) An oxidized tryptophan facilitates copper binding in Methylococcus capsulatus-secreted protein MopE. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13897–13904 10.1074/jbc.M800340200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson K. A., Ve T., Larsen O., Pedersen R. B., Lillehaug J. R., Jensen H. B., Helland R., and Karlsen O. A. (2014) CorA Is a copper repressible surface-associated copper(I)-binding protein produced in Methylomicrobium album BG8. PLOS One 9, e87750 10.1371/journal.pone.0087750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karlsen O. A., Berven F. S., Stafford G. P., Larsen Ø Murrell J. C., Jensen H. B., and Fjellbirkeland A. (2003) The surface-associated and secreted MopE protein of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) responds to changes in the concentration of copper in the growth medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 2386–2388 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2386-2388.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Larsen Ø., and Karlsen O. A. (2016) Transcriptomic profiling of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) during growth with two different methane monooxygenases. Microbiologyopen 5, 254–267 10.1002/mbo3.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Almagro Armenteros J. J., Tsirigos K. D., Sønderby C. K., Petersen T. N., Winther O., Brunak S., von Heijne G., and Nielsen H. (2019) SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 420–423 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wiener M. C. (2005) TonB-dependent outer membrane transport: going for Baroque? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 394–400 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Belchik S. M., Schaeffer S. M., Hasenoehrl S., and Xun L. (2010) A β-barrel outer membrane protein facilitates cellular uptake of polychlorophenols in Cupriavidus necator. Biodegradation 21, 431–439 10.1007/s10532-009-9313-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van den Berg B., Bhamidimarri S. P., and Winterhalter M. (2015) Crystal structure of a COG4313 outer membrane channel. Sci. Rep. 5, 11927 10.1038/srep11927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. LaBauve A. E., and Wargo M. J. (2014) Detection of host-derived sphingosine by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is important for survival in the murine lung. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003889 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dash B. P., Alles M., Bundschuh F. A., Richter O. M., and Ludwig B. (2015) Protein chaperones mediating copper insertion into the CuA site of the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase of Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 202–211 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Banci L., Bertini I., Ciofi-Baffoni S., Katsari E., Katsaros N., Kubicek K., and Mangani S. (2005) A copper(I) protein possibly involved in the assembly of CuA center of bacterial cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3994–3999 10.1073/pnas.0406150102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abriata L. A., Banci L., Bertini I., Ciofi-Baffoni S., Gkazonis P., Spyroulias G. A., Vila A. J., and Wang S. (2008) Mechanism of CuA assembly. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 599–601 10.1038/nchembio.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arslan E., Schulz H., Zufferey R., Kunzler P., and Thöny-Meyer L. (1998) Overproduction of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum c-type cytochrome subunits of the cbb3 oxidase in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 744–747 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen L. M., Sanishvili R., Davidson V. L., and Wilmot C. M. (2010) In crystallo posttranslational modification within a MauG/pre-methylamine dehydrogenase complex. Science 327, 1392–1394 10.1126/science.1182492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Poulos T. L. (2014) Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 114, 3919–3962 10.1021/cr400415k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li X., Fu R., Lee S., Krebs C., Davidson V. L., and Liu A. (2008) A catalytic di-heme bis-Fe(IV) intermediate, alternative to an Fe(IV)=O porphyrin radical. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8597–8600 10.1073/pnas.0801643105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fülöp V., Ridout C. J., Greenwood C., and Hajdu J. (1995) Crystal structure of the di-haem cytochrome c peroxidase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Structure 3, 1225–1233 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00258-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nóbrega C. S., Devreese B., and Pauleta S. R. (2018) YhjA: an Escherichia coli trihemic enzyme with quinol peroxidase activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859, 411–422 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoffmann M., Seidel J., and Einsle O. (2009) CcpA from Geobacter sulfurreducens is a basic di-heme cytochrome c peroxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 393, 951–965 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee Y., Boycheva S., Brittain T., and Boyd P. D. (2007) Intramolecular electron transfer in the dihaem cytochrome c peroxidase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chembiochem 8, 1440–1446 10.1002/cbic.200700159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Geng J., Dornevil K., Davidson V. L., and Liu A. (2013) Tryptophan-mediated charge-resonance stabilization in the bis-Fe(IV) redox state of MauG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9639–9644 10.1073/pnas.1301544110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Geng J., Davis I., and Liu A. (2015) Probing bis-Fe(IV) MauG: experimental evidence for the long-range charge-resonance model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 3692–3696 10.1002/anie.201410247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tarboush N. A., Jensen L. M., Yukl E. T., Geng J., Liu A., Wilmot C. M., and Davidson V. L. (2011) Mutagenesis of tryptophan199 suggests that hopping is required for MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16956–16961 10.1073/pnas.1109423108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Arciero D. M., and Hooper A. B. (1994) A di-heme cytochrome c peroxidase from Nitrosomonas europaea catalytically active in both the oxidized and half-reduced states. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 11878–11886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Prazeres S., Moura J.J., Moura I., Gilmour R., Goodhew C. F., Pettigrew G. W., Ravi N., and Huynh B. H. (1995) Mössbauer characterization of Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c peroxidase: further evidence for redox and calcium binding-induced heme-heme interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24264–24269 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Foote N., Peterson J., Gadsby P. M., Greenwood C., and Thomson A. J. (1985) Redox-linked spin-state changes in the di-haem cytochrome c-551 peroxidase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. J. 230, 227–237 10.1042/bj2300227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pulcu G. S., Frato K. E., Gupta R., Hsu H.-R., Levine G. A., Hendrich M. P., and Elliott S. J. (2012) The diheme cytochrome c peroxidase from Shewanella oneidensis requires reductive activation. Biochemistry 51, 974–985 10.1021/bi201135s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen Y., Naik S. G., Krzystek J., Shin S., Nelson W. H., Xue S., Yang J. J., Davidson V. L., and Liu A. (2012) Role of calcium in metalloenzymes: effects of calcium removal on the axial ligation geometry and magnetic properties of the catalytic diheme center in MauG. Biochemistry 51, 1586–1597 10.1021/bi201575f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Abu Tarboush N., Yukl E. T., Shin S., Feng M., Wilmot C. M., and Davidson V. L. (2013) Carboxyl group of Glu113 is required for stabilization of the diferrous and bis-FeIV states of MauG. Biochemistry 52, 6358–6367 10.1021/bi400905s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shin S., Feng M., Li C., Williamson H. R., Choi M., Wilmot C. M., and Davidson V. L. (2015) A T67A mutation in the proximal pocket of the high-spin heme of MauG stabilizes formation of a mixed-valent FeII/FeIII state and enhances charge resonance stabilization of the bis-FeIV state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 709–716 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fu R., Liu F., Davidson V. L., and Liu A. (2009) Heme iron nitrosyl complex of MauG reveals an efficient redox equilibrium between hemes with only one heme exclusively binding exogenous ligands. Biochemistry 48, 11603–11605 10.1021/bi9017544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li X., Feng M., Wang Y., Tachikawa H., and Davidson V. L. (2006) Evidence for redox cooperativity between c-type hemes of MauG which is likely coupled to oxygen activation during tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis. Biochemistry 45, 821–828 10.1021/bi052000n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shin S., Yukl E. T., Sehanobish E., Wilmot C. M., and Davidson V. L. (2014) Site-directed mutagenesis of Gln103 reveals the influence of this residue on the redox properties and stability of MauG. Biochemistry 53, 1342–1349 10.1021/bi5000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ve T., Mathisen K., Helland R., Karlsen O. A., Fjellbirkeland A., Røhr Å. K., Andersson K. K., Pedersen R. B., Lillehaug J. R., and Jensen H. B. (2012) The Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) secreted protein, MopE*, binds both reduced and oxidized copper. PLOS One 7, e43146 10.1371/journal.pone.0043146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gerlt J. A., Bouvier J. T., Davidson D. B., Imker H. J., Sadkhin B., Slater D. R., and Whalen K. L. (2015) Enzyme function initiative-enzyme similarity tool (EFI-EST): a web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 1019–1037 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gerlt J. A. (2017) Genomic enzymology: web tools for leveraging protein family sequence-function space and genome context to discover novel functions. Biochemistry 56, 4293–4308 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zallot R., Oberg N. O., and Gerlt J. A. (2018) “Democratized” genomic enzymology web tools for functional assignment. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 47, 77–85 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen I. A., Chu K., Palaniappan K., Pillay M., Ratner A., Huang J., Huntemann M., Varghese N., White J. R., Seshadri R., Smirnova T., Kirton E., Jungbluth S. P., Woyke T., Eloe-Fadrosh E. A., Ivanova N. N., and Kyrpides N. C. (2019) IMG/M v.5.0: an integrated data management and comparative analysis system for microbial genomes and microbiomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D666–D677 10.1093/nar/gky901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Finn R. D., Clements J., and Eddy S. R. (2011) HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37 10.1093/nar/gkr367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Finn R. D., Clements J., Arndt W., Miller B. L., Wheeler T. J., Schreiber F., Bateman A., and Eddy S. R. (2015) HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W30–W38 10.1093/nar/gkv397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lawton T. J., Kenney G. E., Hurley J. D., and Rosenzweig A. C. (2016) The CopC family: structural and bioinformatic insights into a diverse group of periplasmic copper binding proteins. Biochemistry 55, 2278–2290 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jones D. T. (1999) Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zimmermann L., Stephens A., Nam S. Z., Rau D., Kubler J., Lozajic M., Gabler F., Söding J., Lupas A. N., and Alva V. (2018) A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2237–2243 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Studier F. W. (2014) Stable expression clones and auto-induction for protein production in E. coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 1091, 17–32 10.1007/978-1-62703-691-7_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., and Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., and Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 10.1107/S0907444911001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.