Abstract

Setting:

Nineteen health facilities in rural, southeastern Malawi.

Objective:

To describe the implementation and results of a 6-week intervention to accelerate human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) case finding.

Design:

Six HIV testing strategies were simultaneously implemented. Routinely collected data from Ministry of Health registers were used to determine the number of HIV tests performed and of new cases identified. The weekly averages of the total number of tests and new cases before and during the intervention were compared. Testing by age group and sex was described. The percentage yield of new cases was compared by testing strategy.

Results:

Of 29 703 HIV tests conducted, 1106 (3.7%) were positive. Of the total number of persons tested, 69.5% were women and 75.5% were aged >15 years. The yield of positive test results was 3.5% among women, 4.3% among men, 4.4% among those aged >15 years and 1.5% among those aged ⩽15 years. The average weekly number of tests increased 106.7% from 3337 to 6896 (P = 0.002). The average weekly number of positive cases identified increased 51.9% from 158 to 240 (P = 0.017). The testing strategy with the highest yield resulted in a 6.0% yield; the lowest was 1.3%. The yield for all strategies, except one, was highest in adult men.

Conclusion:

A multi-strategy approach to HIV testing and counseling can be an effective means of accelerating HIV case finding.

Keywords: HIV, case finding, HTC, Malawi

Abstract

Contexte:

Dix-neuf structures de santé dans le sud-est rural du Malawi.

Objectif:

Décrire la mise en œuvre et les résultats d'une intervention de 6 semaines visant à accélérer la recherche de cas de virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH).

Schéma:

Six stratégies de test VIH ont été simultanément mises en œuvre. Des données recueillies en routine à partir des registres du Ministère de la santé ont été utilisées afin de déterminer le nombre de tests VIH réalisés et les nouveaux cas identifiés. Les moyennes hebdomadaires du nombre de tests et des nouveaux cas ont été comparées avant et après l'intervention. Les tests ont été décrits par tranche d'âge et par sexe. Le rendement en pourcentage des nouveaux cas a été comparé en fonction de la stratégie de test.

Résultats:

Ont été réalisés 29 703 tests VIH ; 1106 (3,7%) ont été positifs. Sur le nombre total de tests, 69,5% ont été réalisés chez des femmes et 75,5% chez des personnes de plus de 15 ans. Le rendement a été de 3,5% chez les femmes, de 4,3% chez les hommes, de 4,4% chez les plus de 15 ans et de 1,5% chez les moins de 15 ans. Le nombre moyen hebdomadaire de tests a augmenté de 106,7% passant de 3337 à 6896 (P = 0,002). Le nombre moyen hebdomadaire de cas positifs identifiés a augmenté de 51,9% passant de 158 à 240 (P = 0,017). La stratégie de test ayant le rendement le plus élevé a abouti à un rendement de 6,0% ; le rendement le plus faible a été de 1,3%. Pour toutes les stratégies sauf une, le rendement a été le plus élevé chez les hommes adultes.

Conclusion:

Une approche à multiples stratégies au HTC peut être un moyen efficace d'accélérer identification des cas de VIH.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Diez y nueve establecimientos rurales de salud en el sureste de Malawi.

Objetivo:

Describir la ejecución y los resultados de una intervención de 6 semanas, encaminada a acelerar la búsqueda de casos de infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH).

Método:

Se introdujeron de manera simultánea seis estrategias de pruebas del VIH. Se utilizaron los datos ordinarios recogidos en los registros del Ministerio de Salud, con el fin de determinar el número de pruebas del VIH realizadas y de nuevos casos detectados. Se compararon los promedios semanales del total de pruebas y de casos nuevos antes de la intervención y durante la misma. Se describen las pruebas por grupo de edad y sexo. Las estrategias de pruebas se compararon en función del rendimiento en la detección de casos nuevos.

Resultados:

Se realizaron 29 703 pruebas del VIH, de las cuales 1106 fueron positivas (3,7%). De todas las pruebas, el 69,5% correspondió a las mujeres y el 75,5% a las mujeres mayores de 15 años. El rendimiento diagnóstico fue de 3,5% en las mujeres, 4,3% en los hombres, 4,4% en los mayores de 15 años y 1,5% en las personas de 15 años o menos. El promedio de pruebas realizadas por semana aumentó un 106,7%, de 3337 a 6896 (P = 0,002). El promedio del número de casos positivos detectados cada semana aumentó un 51,9%, de 158 a 240 (P = 0,017). La estrategia más eficaz ofreció un rendimiento de 6,0%; el rendimiento más bajo fue 1,3%. Todas las estrategias, con la excepción de una, aportaron el rendimiento más alto en los hombres adultos.

Conclusión:

Un enfoque multiestratégico de las pruebas diagnósticas y la orientación sobre el VIH es un medio eficaz de acelerar la búsqueda de casos de infección por el VIH.

In 2014, UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome), set forth the goal of ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.1 To assist countries in achieving this goal, the 90-90-90 targets were established: by 2020, 90% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) will know their status, 90% of PLHIV will receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of PLHIV on ART will have viral suppression.2

Identification of PLHIV is the critical first step on the pathway to achieving epidemic control. In 2017, the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) released a new strategy, emphasizing acceleration of optimized, high-yield HIV testing and counseling (HTC) and treatment approaches and establishing ambitious targets for identifying PLHIV (case finding).3 When testing strategies are appropriately targeted, conducting fewer tests (‘low volume’) should result in increased identification of PLHIV compared to less targeted approaches in which all clients accessing a service delivery point are offered testing (‘high volume’), and testing yield is lower.

In Malawi, where 27.3% of PLHIV are unaware of their HIV status, the Malawi National Strategic Plan for HIV/AIDS 2015–2020 focuses on HIV testing as a gateway to reaching the 90-90-90 targets.4 In line with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations,5,6 the plan emphasizes a scale-up of facility-based testing and a shift in community-based testing to focus on key and vulnerable populations, including family members of PLHIV.7 Despite these calls for a strategic mix of service delivery models, there is a paucity of literature describing the impact of simultaneous implementation of multiple HTC approaches within routine program delivery and the contribution of each strategy to overall case finding.

In August 2017, the Baylor College of Medicine Children's Foundation-Malawi's Tingathe Program8 developed and implemented the Surge, an innovative approach to optimize and accelerate (‘surge’) identification of PLHIV. A United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded project, Tingathe supports the Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) by deploying lay health workers, including HIV diagnostic assistants (HDAs), to health facilities in Central and Southern Malawi.9 The program has been described in detail in the referenced publications. The Surge involved the simultaneous implementation of multiple testing strategies, enhanced supervision by senior staff, increased physical testing space, and rapid data feedback over a 6-week period. The aim of the Surge was to rapidly increase the HIV testing yield and identification of PLHIV in response to ambitious targets and timelines in a thoughtful and effective manner. This paper describes the implementation and impact of the Surge in Mangochi District, Malawi.

METHODS

Setting and program description

Tingathe (‘yes we can’) is a program funded by USAID via PEPFAR that utilizes lay health workers to conduct HTC and ensure delivery of comprehensive HIV services at health facilities and in the community.8,10,11 The Surge was implemented in Mangochi, a rural district in Southeastern Malawi with a population of over 1.1 million, an adult HIV/AIDS prevalence of 9.6% in 2017,12 and a proxy linkage to treatment rate of 89%. Tingathe has supported Mangochi District since 2014. The Surge was implemented in 19 Tingathe-supported health facilities over 6 weeks from August to September 2017. This was a descriptive longitudinal evaluation of routine program implementation. The study population included all clients accessing HIV testing services.

Description of the intervention

The Surge design included 1) the development of a package of six testing strategies to optimize testing coverage and yield; five of the strategies were employed at all 19 sites, while evening testing was employed only at the two sites with inpatient services (Table 1); 2) the deployment of enhanced supervision utilizing a paired approach by temporarily relocating experienced supervisors from other districts to offer one-on-one mentorship and support to new supervisors; 3) increased physical testing space by strategically placing tents at high patient-volume facilities; 4) the creation of a robust Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) coding system to track testing strategies (Table 1), and weekly feedback reports depicting case identification by strategy and progress towards case identification targets at facility and district level. Testing strategy codes were recorded in each facility's HTC registers for every test performed. Performance feedback was provided daily from district- to facility-level teams using online messaging. Weekly feedback was provided through meetings and facility information sheets. Feedback reports were reviewed weekly by Tingathe leadership at facility, district and central level, and used to evaluate the effectiveness of each strategy and to adjust interventions accordingly; and 5) the orientation of the facility (including HDAs and clinical staff) to the testing package and M&E system.

TABLE 1.

Strategies for identifying PLHIV deployed at 19 health facilities during the Tingathe Surge testing initiative, Malawi, August–September 2017

| Strategy (register code) | Description |

|---|---|

| Minimum package of interventions for all surge facilities | |

| PITC | Clients at inpatient (adult, pediatric, NRU, labor wards, TB) and outpatient (antenatal clinic, STI clinic, family planning clinic, outpatient nutritional therapeutic program, supplemental feeding program) service delivery points are screened for HTC eligibility (never been tested or tested negative >3 months prior) by health care providers and offered on-site HIV testing |

| Enhanced OPD | After a health talk about the advantages of knowing one's HIV status, OPD clients' health passports are screened for the date of last HTC and signs of HIV-associated illness; those who choose to access testing services are fast-tracked to see the clinician |

| ICT | Clients in the active ART cohort and all HTC clients are screened for untested family members/sexual contacts; untested contacts are invited by the index client to return for testing through a passive referral approach by providing a Family Referral Slip to contacts who are unaware of their HIV status |

| Weekend testing days (WT) | HIV testing is offered during the weekend at inpatient and outpatient settings to ensure PITC and VCT access. An emphasis is placed on Weekend Facility-Based Testing ‘Family Testing Days’, in which weekend fast-tracked testing is available for those referred by ICT clients |

| Mobile clinic outreach testing (OUT) | Clients are offered testing during regularly scheduled outreach clinics in which routine clinical services are provided on a rotating basis in the community (i.e., antenatal clinic, family planning clinics, under-5 clinics, voluntary medical male circumcision clinics) |

| Targeted community testing events (TCT) | Specially organized community testing events targeting hard-to-reach populations or workplaces. Events are structured to facilitate testing at convenient times and locations for populations with known high prevalence rates such as sex workers, fishermen, prisoners, policemen, bicycle taxi drivers, as well as for clients with less access to testing (e.g., men). Events are coordinated through partnership with other organizations and influential leaders of key populations, who provide directed messaging prior to events to ensure that targeted populations (vs. the general public) access testing. During these events, clients who have not previously undergone testing or those considered to be high risk for acquiring HIV according to the Malawi HTC guidelines are offered HIV testing |

| Other (OTH) | Includes any additional voluntary patient-initiated counseling and testing |

| Additional interventions for facilities with inpatient services | |

| Inpatient testing during evening hours (ET) | Carried out in large facilities with inpatient wards, this supplementary service provides access to PITC services for clients, guardians, and VCT clients during evening hours, preventing a backlog of patients requiring testing in the morning or patients being discharged without access to testing services |

PLHIV = people living with the human immunodeficiency virus; PITC = provider initiated testing and counseling; NRU = nutritional rehabilitation unit; TB = tuberculosis; STI = sexually transmitted infections; HTC = HIV testing and counseling; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; OPD = outpatient department screening; ICT = index case testing; ART = antiretroviral therapy; VCT = voluntary counseling and testing.

Prior to the Surge, all facilities provided HTC services, but implementation of various case finding strategies was inconsistent, with missed opportunities for HIV testing and inconsistent review of site performance to inform programming. The Surge helped to standardize the services, ensuring strategies were employed consistently across facilities, and to rigorously evaluate implementation to assess the effectiveness and contribution of each strategy to overall case finding. Tingathe lay health workers were responsible for conducting HIV screening and testing, linkage to treatment and care, and documentation in registers. Eligibility for HIV testing was defined by MOH policy,13 and testing was offered to those with signs and symptoms of HIV disease, those who had never been tested or had tested negative >3 months previously. A positive HIV test was followed by ART initiation for all in accordance with Malawi MOH national treatment guidelines, which adopted Test and Treat in 2016.14 The program tools and standard operating procedures are available at info@tingathe.org.

Data collection and analysis

Tingathe program data are collected monthly from health facility registers, collated, and analyzed for program reporting purposes. During the Surge, de-identified aggregate data from HIV testing registers were collected and reported weekly to measure progress and inform decision-making. To assure data quality, weekly Surge reports were compared to routinely collected monthly reports, and discrepancies were resolved by rechecking the source register. Coding was implemented at the beginning of the Surge. All tests recorded in HTC registers were given a code (Table 1) to indicate testing strategy. Testing acceptance rates are not recorded as routine program data.

Prior to the Surge, routinely collected data included number and outcome of HIV tests administered per month but did not include the test date; calculation of the exact weekly averages in the weeks before the Surge was therefore not possible. A weekly ‘pre-surge’ average was calculated based on combined tests administered in May, June, and July 2017, divided by the number of weeks in that period. As Surge data collection systems were optimally functioning from Week 3 of the Surge, data from Weeks 3–6 were analyzed for this paper.

The data were cleaned and consolidated using Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). The total number of tests, positive results, and yield (positive results divided by total number of tests) were tabulated by sex and age. Weekly averages for tests and positive cases identified were calculated for the pre-Surge and Surge periods. To compare the mean weekly values before and during the Surge, a paired sample t-test was performed using SPSS v20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The total number of tests, positives, and yield were tabulated by testing strategy code.

Patient-level linkage-to-care data were not collected. As a proxy linkage estimate, we used the number of new ART initiations divided by the number of new PLHIV identified for the given time period.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the National Health Science Research Committee (Lilongwe, Malawi) and the Baylor College of Medicine Institution Review Board (Houston, TX, USA) under a protocol granting review of routine Tingathe program data. Because all data were routine programmatic facility-level data, with no individual information collected, patient-level consent was not obtained.

RESULTS

In total, 29 703 HIV tests were conducted, 1106 of which were positive (3.7% overall testing yield, 90% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–7.5) (Table 2). Of the total number of tests, 69.5% were carried out among women and 75.5% were among those aged >15 years. The HIV-positive testing yield was 3.5% (713/20 639) among women, 4.3% (393/9064) among men, 4.4% (994/22 434) among those aged >15 years, and 1.5% (112/7269) among those aged ⩽15 years.

TABLE 2.

Testing yield (new positives/total number of tests) for each testing strategy during the Tingathe Surge by age group and sex

| Age group, years | 1–9 years | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | 20–24 years | 25–49 years | ⩾50 years | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | F % (n/N) | M % (n/N) | % (n/N) | |

| PITC | 1.1 (1/94) | 6.3 (5/79) | 1.4 (16/1136) | 0 (0/86) | 1.6 (12/761) | 1.5 (10/684) | 2.5 (46/1842) | 1.7 (4/237) | 4.7 (116/2489) | 6.5 (36/551) | 4.8 (5/105) | 9.6 (8/83) | 3.2 (259/8147) |

| Enhanced OPD | 0.7 (2/268) | 2.8 (5/181) | 1.6 (14/872) | 1.2 (3/251) | 2.2 (18/809) | 1.0 (7/706) | 3.0 (45/1487) | 2.7 (9/337) | 6.8 (185/2710) | 10 (113/1130) | 4.0 (28/694) | 6.9 (27/392) | 4.6 (456/9837) |

| ICT | 2.6 (3/115) | 1.2 (1/86) | 5.4 (2/37) | 2.4 (1/42) | 3.2 (7/221) | 3.3 (6/184) | 13.5 (5/37) | 5.1 (2/39) | 14.0 (12/86) | 13.5 (10/74) | 9.7 (3/31) | 17.9 (7/39) | 6.0 (59/991) |

| WT | 1.3 (3/237) | 0 (0/105) | 0.6 (2/309) | 1.1 (1/93) | 1.3 (3/231) | 1.4 (3/214) | 3.7 (11/296) | 2.4 (2/82) | 7.6 (37/489) | 8.9 (23/258) | 1.6 (1/63) | 4.6 (3/65) | 3.6 (89/2442) |

| OUT | 1.0 (4/399) | 0.7 (1/149) | 0.9 (4/450) | 1.3 (2/157) | 1.4 (3/207) | 0.6 (1/166) | 1.1 (4/355) | 3.1 (4/130) | 3.6 (21/584) | 6.9 (18/261) | 3.7 (5/136) | 5.1 (4/79) | 2.3 (71/3073) |

| TCT | 0 (0/248) | 1.9 (2/106) | 0.3 (1/388) | 0.3 (1/ 368) | 0.6 (1/175) | 2.8 (4/142) | 3.5 (13/373) | 1.6 (5/307) | 2.7 (20/736) | 4.5 (22/485) | 5.9 (11/188) | 6.1 (11/180) | 2.5 (91/3696) |

| ET | 0 (0/4) | 0 (0/2) | 0 (0/43) | 0 (0/4) | 0 (0/18) | 0 (0/16) | 0 (0/38) | 12.5 (1/8) | 1.6 (1/61) | 4.5 (1/22) | 0 (0/7) | 0 (0/16) | 1.3 (3/239) |

| Other* | 5.4 (2/37) | 0 (0/10) | 1.7 (2/116) | 1.6 (1/64) | 5.3 (2/38) | 9.1 (2/22) | 5.6 (11/198) | 2.1 (2/94) | 7.6 (29/382) | 10.3 (24/234) | 5.1 (2/39) | 2.3 (1/44) | 6.1 (78/1278) |

| Total | 3.3 (46/1402) | 4.6 (33/718) | 0.4 (15/3351) | 1.3 (14/1065) | 1.7 (41/2460) | 0.4 (9/2134) | 2.9 (135/4626) | 2.4 (29/1234) | 5.6 (421/7537) | 8.2 (247/3015) | 4.4 (55/1263) | 6.8 (61/898) | 3.7 (1106/29703) |

*Voluntary testing.

F = female; M = male; PITC = provider initiated testing and counseling; OPD = outpatient department screening; ICT = index case testing; WT = weekend testing; OUT = mobile clinic outreach; TCT = targeted community testing; ET = evening hours testing.

The average weekly number of tests performed increased 106.7% during the Surge from 3337 to 6896 (P = 0.002). Weekly testing increases were higher among women (112% increase) than men (75% increase), and higher among children aged <15 years (182% increase) than among those aged ⩾15 years (115%). The average weekly number of positive cases identified increased 51.9%, from 158 to 240 (P = 0.017). The testing yield decreased from 4.7% to 3.5%.

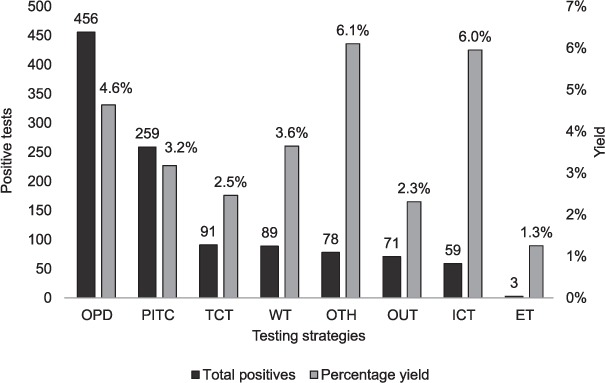

Of the strategies employed and coded in the HTC register, patient-initiated testing (VCT) (coded as ‘OTH’) had the highest yield (6.1%). Index case testing (ICT) resulted in the next-highest yield (6.0%) across sex and age categories, followed by outpatient department (OPD) testing (4.6%) (Figure). Evening testing (ET) resulted in the lowest yield (1.3%), although the yield was considerably higher among adult men (2.9%) than among women and children (<1%) (Table 2). The yield for all strategies, except ICT, was highest in adult men. OPD testing resulted in the largest number of clients tested (n = 9837), and the identification of the highest number of PLHIV (n = 456), followed by provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC) (8147 tested, 259 newly identified PLHIV). All testing strategies resulted in more women tested than men (Table 3). The highest proportion of women (78.9%) underwent PITC, while the highest proportion of men (46.8%) underwent ICT. A total of 10 276 young adults (aged 15–24 years) received HTC, 214 of whom were identified as PLHIV (2.1%), the majority of whom were female (Table 4).

FIGURE.

Total persons living with HIV identified and testing yield during the Tingathe Surge by testing strategy. OPD = outpatient department screening; PITC = provider-initiated testing and counseling; TCT = targeted community testing events; WT = weekend testing; OTH = other voluntary patient-initiated testing; OUT = mobile outreach clinic testing; ICT = index case testing; ET = evening testing.

TABLE 3.

Total number of tests administered, testing yield, and proportion of women and men tested for each testing strategy during the Tingathe Surge

| Testing strategy | Tests N | Women tested n (%) | Yield in women % | Men tested n (%) | Yield in men % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider-initiated testing and counseling | 8147 | 6427 (78.9) | 3.0 | 1720 (21.1) | 3.7 |

| Enhanced outpatient department screening | 9837 | 6840 (69.5) | 4.3 | 2997 (30.5) | 5.5 |

| Index case testing | 991 | 527 (53.2) | 6.1 | 464 (46.8) | 5.8 |

| Weekend testing days | 2442 | 1625 (66.5) | 3.5 | 817 (33.5) | 3.9 |

| Mobile clinic outreach | 3073 | 2131 (69.3) | 1.9 | 942 (30.7) | 3.2 |

| Targeted community testing | 3696 | 2108 (57.0) | 2.2 | 1588 (43.0) | 2.8 |

| Testing during evening hours | 239 | 171 (71.5) | 0.6 | 68 (28.5) | 2.9 |

| Other/voluntary testing | 1278 | 810 (63.4) | 5.9 | 468 (36.6) | 6.4 |

| Total | 29703 | 20639 (69.5) | 3.5 | 9064 (30.5) | 4.3 |

TABLE 4.

Testing yield (new positives/total tests) for adolescents and young people (15–24 years) for each testing strategy by sex during the Tingathe Surge, Malawi

| Women % (n/N) | Men % (n/N) | Total % (n/N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider initiated testing and counseling | 2.1 (62/2978) | 1.2 (4/323) | 2.0 (66/3301) |

| Enhanced outpatient department screening | 2.5 (59/2359) | 2.0 (12/588) | 2.4 (71/2947) |

| Index case testing | 9.5 (7/74) | 3.7 (3/81) | 6.5 (10/155) |

| Weekend testing days | 2.1 (13/605) | 1.7 (3/175) | 2.1 (16/780) |

| Mobile clinic outreach | 1.0 (8/805) | 2.1 (6/287) | 1.3 (14/1092) |

| Targeted community testing | 1.8 (14/761) | 0.9 (6/675) | 1.4 (20/1436) |

| Testing during evening hours | 0.0 (0/81) | 8.3 (1/12) | 1.1 (1/93) |

| Other/voluntary testing | 4.1 (13/314) | 1.9 (3/158) | 3.4 (16/472) |

| Total | 2.2 (176/7977) | 1.7 (38/2299) | 2.1 (214/10276) |

The number of new clients initiating ART increased 26.5% during the Surge, from a weekly average of 147 to 186 (P = 0.025). Over the 4-week period, 787 PLHIV were initiated on ART: 505 were female (64.2%), 282 were male (35.8%); 82 were aged <15 years (10.4%), and 705 were aged ⩾15 years (89.6%). While overall ART initiation increased, using this number as a proxy for linkage to care (number of new ART initiates/number of new PLHIV), weekly linkage decreased from 93.0% (147/158) before the Surge to 77.5% (186/240) during the Surge. The demographics of new initiates by age and sex did not significantly differ pre- and post- Surge.

Thirteen targeted community testing (TCT) events took place during the 4 weeks of the Surge (Table 5). The highest yield event involved testing Mangochi Prison inmates.

TABLE 5.

Description of targeted community testing events conducted during the Tingathe Surge, Malawi, August–September 2017

| Target population | Events n | Tested n | PLHIV identified n | Yield % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prison inmates | 1 | 53 | 4 | 8 |

| Factory/estate workers | 2 | 832 | 44 | 5 |

| Client support groups | 4 | 569 | 10 | 2 |

| Fisher folk | 5 | 801 | 33 | 4 |

| Police officers | 1 | 32 | 1 | 3 |

PLHIV = people living with the human immunodeficiency virus.

DISCUSSION

Implementation of the Surge demonstrated that rapid scale-up of a multi-strategy approach to case finding in a programmatic setting is feasible and resulted in a dramatic increase in testing and the number of PLHIV identified. The intervention also revealed that no single strategy resulted in both a high testing yield and a large number of new PLHIV identified. VCT remains an important, high-yield access point for case identification. Targeted strategies such as ICT had higher yield for case finding, but lower yields in terms of new cases identified due to lower numbers of clients tested. Higher-volume strategies such as OPD and PITC, where large numbers of clients were offered HTC, resulted in lower yields than ICT but resulted in more PLHIV identified. To optimize the identification of PLHIV, both high-yield, low-volume and high-volume, lower-yield strategies were required.

Contributions of testing strategies

Finding a balance between high-yield and high-volume strategies is critical to optimizing case identification. The ideal balance varies among facilities and is likely dependent upon size and the specific population(s) served.

Due to the high likelihood of infection among sexual partners of HIV-infected persons, ICT is a priority and should be optimized. ICT as a strategy implemented during the Surge had the highest yield, yet was low volume, contributing only 3.3% of the total tests conducted and 5.3% of new diagnoses. Yield among clients aged >15 years who underwent ICT was slightly higher than the estimated district-level HIV prevalence of 10.1%.12 ICT approaches that include provider-assisted partner notification and community-based follow-up have demonstrated increased testing uptake in similar settings,15 and would likely increase the number of PLHIV identified if this strategy is used.

PITC provides ready access to HTC for patients seeking inpatient and outpatient care at service delivery points in which determination of HIV status is a critical element of the diagnostic workup. Providing HTC in OPDs makes it possible to identify PLHIV earlier in their course of disease.16,17 PITC and OPD testing are high-volume, low-yield strategies. Yields from PITC and OPD testing were lower than ICT; however, nearly two thirds of the total PLHIV identified during the Surge came from PITC and OPD testing. Ensuring that HIV testing is offered on an opt-out basis for these patients remains a priority.

Additional strategies (ET, weekend testing, mobile clinic outreach testing and TCT) were deployed to increase testing access for clients (particularly men and key populations) by offering extended hours and geographic alternatives to facility-based testing. These strategies varied in yield and contribution to overall case identification. WT was the highest-yielding strategy among men and women aged 25–49 years, suggesting that offering testing services outside of routine facility hours improves access for this cohort. The TCT strategy was employed to target key populations who might not otherwise access testing by providing services at customized times and locations. TCT resulted in a large volume of HIV testing, and, despite a relatively low yield, remains an important means of reaching first-time testers and hard-to-reach populations who may not present at a health facility.18–21 Uptake of extended hours and community testing was likely limited by low awareness of service availability due to the brief nature of the Surge intervention. Improved community awareness of these services would likely increase testing uptake for these strategies and further extend access for populations with geographic and time limitations.

While a robust cost-analysis was not performed, it should be noted that implementation of the Surge required reallocation of resources for training, supervision, monitoring feedback, and procurement of tents for additional testing space. TCT events accrued the most additional expenses for transportation, personnel (drivers), and venues.

Testing in young women

Only one half of HIV-infected young adults aged 15–24 years in Malawi are currently aware of their status,4 and many young people are reluctant to seek testing services as they do not consider themselves at risk.22 During the Surge, new HIV infections were diagnosed in 176 women aged 15–24 years, representing almost one fourth of the women identified. ICT was the highest yield strategy for this group, although it only identified seven new PLHIV. By contrast, PITC had low yield, but resulted in 62 new young women with HIV identified due to the large number of tests performed during antenatal screening.

Testing in men

Men are less likely to be tested for HIV than women in sub-Saharan Africa,23 and tend to access testing services later in the course of the disease. Community-based testing strategies may be more effective in reaching men.18 Our data support this, with a high percentage of men accessing testing through TCT compared to other strategies: 43% of those tested through TCT were men, vs. 31% of men tested overall. Testing the partners of newly diagnosed women is also an effective way to increase the number of men tested, particularly when partner notification is assisted by health care workers.24 During the Surge, ICT resulted in the highest percentage of men accessing testing. This suggests that enhancing assisted partner notification coupled with TCT strategies might increase case finding among men.

The success of the Surge was attributed to several key factors: 1) the establishment of clear definitions for multiple strategic testing approaches and identification of a minimum baseline package of strategies for all facilities; 2) regular organized supervision; 3) increased testing space; and 4) routine data reviews resulting in timely adjustment of approaches tailored to specific facility needs.

As a result of the Surge findings, sustained modifications were made to Tingathe programming. Various testing strategies were prioritized and de-prioritized depending on site-specific factors affecting success, with many sites discontinuing non-targeted TCT activities. Index case testing was further scaled up beyond the 19 Surge sites.

Looking forward: continuing to optimize case identification

As the number of undiagnosed PLHIV decreases globally, a focus on case identification approaches targeting those at highest risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV will be critical to ensuring continued progress. In addition to ensuring HIV testing access through traditional approaches such as PITC, OPD testing, ICT, and VCT, layering in innovative approaches should allow for further targeted testing. Incorporating HIV recency testing into testing programs alongside optimized ICT strategies may allow for the identification of clients at highest risk for transmission, and in turn, the identification of newly infected sexual partners and the prevention of new infections.25 Increasing access to testing for hard-to-reach populations through extended hours and community testing may be supplemented by innovative strategies such as facility- and community-based self-testing, in which a client can perform an HIV test and interpret the result in private.26

Limitations of the study

As coding of test by strategy was initiated during the Surge period, comparisons of yield and the number of PLHIV identified by specific strategy pre- vs. during-Surge was not possible. as the data represent the number of HIV tests rather than individual client results, we were unable to account for repeat testing, but we do not believe this significantly impacts the reported outcomes. Furthermore, the Surge was a short and intensive intervention over a 6-week period, with analyzable data for only 4 weeks, limiting our ability to draw definitive conclusions, as well as limiting our ability to increase community awareness of services. While the objective of this paper was to describe the short-term impact of a rapid, brief intervention to improve case finding, it will be important to describe the longer-term effects. Finally, because patient-level data were not collected, we were unable to definitively describe linkage to care, but used the number of new ART initiations as a proxy for linkage, likely underestimating true linkage to care.

CONCLUSION

The Tingathe Surge was a multi-strategy approach to case finding that allowed for a methodical yet rapid approach to optimize testing yield and identification of PLHIV by defining a minimum package of recommended interventions. The Surge demonstrated that a balance between low yield but high volume, and high yield but low volume strategies with organized supervision, increased testing space, and ongoing review of performance data accelerated the identification of PLHIV.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clients and health workers in participating facilities, the Malawi Ministry of Health (Lilongwe) for its partnership, and the Baylor College of Medicine Children's Foundation Malawi (Lilongwe) for its support.

This study was made possible by support from the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR, Washington, DC, USA) through USAID (Washington, DC, USA) under the Cooperative Agreement Technical Support for PEPFAR Programs in Southern Africa (TSP), (AID-674-A-16-00003). MHK was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Bethesda, MD, USA) (K01 TW009644). The contents of this article are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders, including the NIH, USAID and the US Government.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS World AIDS Day report: fast-track- ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS 90–90–90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Agency for international Development PEPFAR Strategy for accelerating HIV/AIDS epidemic control (2017–2020) Washington, DC, USA: USAID; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malawi Ministry of Health Malawi Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment 2015–2016. Lilongwe, Malawi: MOH; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Service delivery approaches to HIV testing and counseling (HTC): a strategic HTC programme framework. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malawi Ministry of Health National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS 2015–2020. Lilongwe, Malawi: MOH; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M H, Ahmed S, Buck W C et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 2) doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17389. 17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flick R J, Simon K R, Nyirenda R et al. The HIV diagnostic assistant—early findings from a novel HIV testing cadre in Malawi. AIDS. 2019;33(7):1215–1224. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed S, Kim M H, Dave A C et al. Improved identification and enrolment into care of HIV-exposed and -infected infants and children following a community health worker intervention in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18 doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19305. 19305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M H, Ahmed S, Preidis G A et al. Low rates of mother-to-child HIV transmission in a routine programmatic setting in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064979. e64979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malawi National Statistics Office Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–2016. Lilongwe, Malawi: NSO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malawi Ministry of Health Malawi HIV testing services guidelines. Lilongwe, Malawi: MOH; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malawi Ministry of Health Clinical management of HIV in children and adults. Lilongwe, Malawi: MOH; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalal S, Johnson C, Fonner V et al. Improving HIV test uptake and case finding with assisted partner notification services. AIDS. 2017;31(13):1867–1876. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalal S, Lee C W, Farirai T et al. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling: increased uptake in two public community health centers in South Africa and implications for scale-up. PLoS One. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027293. e27293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kayigamba F R, Bakker M I, Lammers J et al. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in Rwanda: acceptability among clinic attendees and workers, reasons for testing and predictors of testing. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095459. e95459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma M, Barnabas R V, Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men's engagement in the HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002262. e1002262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meehan S A, Draper H R, Burger R, Beyers N. What drives ‘first-time testers’ to test for HIV at community-based HIV testing services? Public Health Action. 2017;7(4):304–306. doi: 10.5588/pha.17.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meehan S A, Naidoo P, Claassens M M, Lombard C, Beyers N. Characteristics of clients who access mobile compared to clinic HIV counselling and testing services: a matched study from Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:658. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0658-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S77–S85. doi: 10.1038/nature16044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price J T, Rosenberg N E, Vansia D et al. Predictors of HIV, HIV risk perception, and HIV worry among adolescent girls and young Wwomen in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2018;77(1):53–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Agency for International Development Demographic patterns of HIV testing uptake in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, USA: USAID; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hensen B, Taoka S, Lewis J J, Weiss H A, Hargreaves J. Systematic review of strategies to increase men's HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(14):2133–2145. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Surveillance of recent HIV infections: using point-of-care recency tests to rapidly detect and respond to recent infections. Washington, DC, USA: PEPFAR; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization HIV self-testing. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. [Google Scholar]