Abstract

DNA methylation at CpG sites is an essential epigenetic mark that regulates gene expression during mammalian development and diseases. Methylome refers to the entire set of methylation modifications present in the whole genome. Over the last several years, an increasing number of reports on brain DNA methylome reported the association between aberrant methylation and the abnormalities in the expression of critical genes known to have critical roles during aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, the role of methylation in understanding neurodegenerative diseases has been under focus. This review outlines the current knowledge of the human brain DNA methylomes during aging and neurodegenerative diseases. We describe the differentially methylated genes from fetal stage to old age and their biological functions. Additionally, we summarize the key aspects and methylated genes identified from brain methylome studies on neurodegenerative diseases. The brain methylome studies could provide a basis for studying the functional aspects of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Aging, Alzheimer’s disease, Brain methylome, CpG island, DNA methylation, Epigenetic clock, Neurodegenerative diseases

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetic processes are characterized by their ability to regulate gene expression by altering the chromatin structure or its associated proteins in a manner independent of alterations in DNA sequences. Epigenetic modifications can be categorized into two groups as DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation, histone modifications.

DNA methylation was first identified in the early 1950s as the best understood modifications among the epigenetic processes (1, 2). 5-methylcytosine (5mC) is often referred to as the fifth base of the DNA code. DNA methylation involves covalent attachment of a methyl group (CH3) to the fifth position of carbon in the cytosine within CG dinucleotides with resultant formation of 5mC. The symmetrical CG dinucleotides are also called as CpG, due to the presence of phosphodiester bond between cytosine and guanine. The human genome contains short lengths of DNA (~1,000 bp) in which CpG is commonly located (~1 per 10 bp) in unmethylated form and referred as CpG islands; they commonly overlap with the transcription start sites (TSSs) of genes. In human DNA, 5mC is present in approximately 1.5% of the whole genome and CpG base pairs are 5-fold enriched in CpG islands than other regions of the genome (3, 4). CpG islands have the following salient features. In the human genome, more than 60% of mammalian gene promoters are enriched with CpG islands. The CpG islands are generally hypomethylated in every tissue during all stages of development. In the human brain, the methylation of CpG dinucleotides fluctuates largely across the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and pons (5). DNA methylation levels are gradually enhanced in the human cerebral cortex at many genomic loci at the time of maturation and aging. In addition, both hypermethylation at HOXA1, PGR, and SYK loci and hypomethylation at S100A2 loci are observed in cortical neurons of aged samples (6). This bidirectional methylation variation during lifespan indicates that methylation levels are regulated dynamically in differentiated neurons.

The role of DNA methylation in gene expression depends on the genomic CpG location. Methylation at gene promoter or enhancer region is inversely correlated with gene expression (7, 8) whereas gene body methylation is positively associated with transcription (9–11). The repression of transcription by DNA methylation is explained by two mechanisms, a) methylated cytosine in CpG dinucleotide is identified by 5-methylcytosine-binding transcription factor (MeCP2), that recruit co-repressor protein complexes such as mSin3A and histone deacetylases thereby causing gene repression (12), b) hypermethylation blocks the recognition of transcription factor NRF1 binding sites and result in transcription repression (13). It is not surprising to note that DNA methylation controls several processes including gene expression in X-chromosome inactivation (14), genomic imprinting (15, 16), long-term memory formation (17), carcinogenesis (18), and virus, transposons or retrovirus silencing (19) to ensure genomic stability (20).

The transfer of methyl groups to the DNA from donor S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) is catalyzed by a group of enzymes referred to as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). The DNMT1, DNMT2, and DNMT3 enzymes are the key members of the DNMT family (21). During development, tissue-specific DNA methylation patterns are established by de novo DNA methyltransferases such as DNMT3A and DNMT3B (22). Subsequently, DNA methylation is sustained during cell division by DNMT1 (23). The DNMT3A and DNMT3B are essential for methylation at CpG and non-CpG positions (24). The evidence proves that there is a context-dependent expression of these enzymes depending on the cell type and the brain regions. For example, the differentiated neurons and oligodendrocytes exhibit high endogenous expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A but same is not the case with astroglia (25). Post-mortem human brain shows differential expression of these enzymes in the layers III and V of the cortex (6, 26).

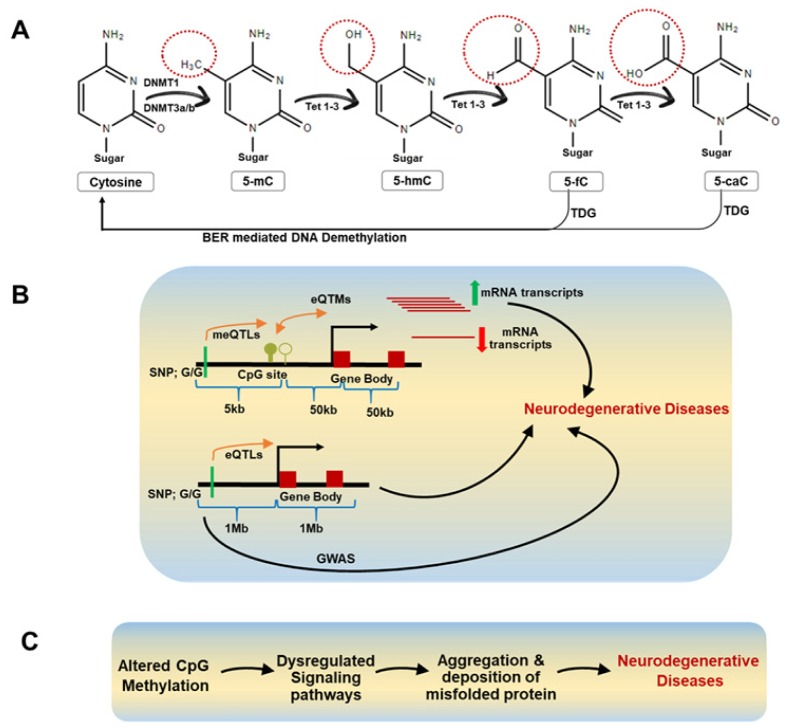

Demethylation of DNA can be achieved by either passive or active ways. DNA methylation marks are maintained in a bonafide manner by the catalytic activity of DNMT1 and ubiquitin-like plant homeodomain and RING finger domain 1 (UHRF1) on the hemimethylated newly replicated DNA. Loss of DNMT1 and UHRF1 activity results in passive DNA demethylation. Alternatively, the concept of active DNA demethylation defined as the elimination of 5mC in a replication free manner was discovered a decade ago. The two seminal papers discovered that Ten-eleven translocation family of protein dioxygenases (TET1-3) are responsible for active demethylation leading to the production of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) that is highly present in neurons and embryonic stem (ES) cells (27, 28). Tet proteins acts on 5 methylcytosine leading to sequential oxidation with subsequent generation of 5-hmC, 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (5-caC) (29, 30). The 5-hmC is also called as the sixth letter of the DNA code. Eventually, 5-fC and 5-caC are specifically identified and excised by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG). TDG has the ability to catalyze the glycosidic bond between the base and deoxyribose sugar of DNA resulting in abasic sites, which are eventually replaced with unmethylated cytosines by base excision repair (BER) mechanism (Fig. 1A) (31, 32). In addition, DNA repair enzymes such as GADD45 and AID/APOBEC also mediate active demethylation (33–35). Embryonic stem (ES) cells exhibit high expression levels of Tet1 and Tet2 and low expression levels of Tet3 (36). In the adult brain, all the Tet enzymes are equally expressed (37). TET 1/2 double knockout in ES cells leads to developmental defects like mid-gestation abnormalities with perinatal lethality (38).

Fig. 1.

DNA methylation and its consequences. (A) DNA methylation and TET mediated DNA demethylation. Cytosine (C) is methylated at 5th carbon of the pyrimidine ring by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) to form 5-methylcytosine (5-mC). Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET1-3) enzymes sequentially act on 5mC to generate 5 hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5-fC), and finally 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC). The 5fC and 5caC are excised directly by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG). The resulting abasic sites, which are generated by TDG since it has the ability to catalyze the glycosidic bond between the base and deoxyribose sugar of DNA, are eventually replaced with unmethylated cytosines by base excision repair (BER). (B) Relationship between SNP, CpG site, eQTLs, mQTLs, and neurodegenerative diseases. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have identified several Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) which indicate differences in the inheritance of diseases. The single base pair changes in the DNA sequence can affect the gene expression levels and referred to as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs). Methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs) are the individual DNA sequence variation at specific loci that can cause changes in DNA methylation patterns of CpG sites. Significant correlation of methylation mark with gene expression is termed as expression Quantitative Trait Methylations (eQTMs). Recent studies have shown that eQTLs, meQTLs, and eQTMS are linked with neurodegenerative diseases. (C) Differential CpG methylation and its association with neurodegenerative diseases.

The single base pair changes in the DNA sequence, which can influence the levels of gene expression, are called an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs). Methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs) are the individual DNA sequence variation at specific loci that can cause changes in DNA methylation patterns of CpG sites (Fig. 1B). The meQTLs have been found to overlap with eQTLs and exhibit similar biological mechanism by which the DNA sequence variation affects both expression and methylation. The presence of meQTLs at regulatory sequences can result in altered binding of transcription factors thereby leading to changes in transcription events. Importantly, the meQTL can have an impact on gene regulation based on developmental stage and environment. Traditionally, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations are known to linked to differences in inheritance to a range of diseases. Similarly, recent researches have shown that meQTLs can also act as biomarkers for the diagnosis of various diseases.

Analysis of DNA methylation aimed at quantifying the total amount of 5-methylcytosine in the genome is termed as global methylation analysis and elucidation of the methylation status of the specific gene loci is called as local methylation analysis. The bisulfite sequencing is the benchmark for the local methylation analysis, although the amplification of long DNA fragments is hard due to DNA fragmentation. Restriction enzyme-based assay depends on the usage of the methylation-sensitive enzyme, HpaII, and methylation insensitive enzyme, MspI at gene-specific loci. The hypermethylation and hypomethylation at specific gene loci have been associated with various diseases (39). Profiling of methylation at base pair level throughout the genome is termed as methylome. The selection of method for analysis of DNA methylation landscape of the genome depends on the examination of the CpG, CpH (H = A, C, or T), and 5-hmC modifications. The whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) where the denatured DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite followed by PCR and sequencing the amplified DNA provides information about single-base pair resolution methylation status. The WGBS can detect the CpG and CpH methylation status, but exhibit an inability in differentiating between 5mC and 5-hmC. The Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing (TABseq), which can identify 5-hmC at single-base resolution, overcome the drawback associated with WGBS. TABseq involves the treatment of genomic DNA with β-glucosyltransferase followed by recombinant Tet1 and bisulfite treatment. The reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) is a high-throughput technique that involves the combination of both methylation insensitive restriction enzymes and bisulfite sequencing to enrich the CpG-containing regions of the genome. The application involves digestion of DNA samples with MspI and attachment of the digested ends with adapters followed by ligation. Final steps involve bisulfite conversion, PCR amplification, library preparation, and sequencing. RRBS reveals the methylation status of DNA but not the levels of CpG vs. 5-hmC. Affinity enrichment-based analysis employs affinity purification involving methyl-CpG-binding domain protein1 (MBD1), which recognizes and binds with methylated CG sites, or immunoprecipitation of the sonicated DNA with antibodies specific to 5mC or 5-hmC. The enriched fragment libraries are generated and sequenced to identify DNA modification of interest (40).

GENOME-WIDE STUDIES ADDRESSING THE BRAIN METHYLOME DURING AGING

The process of aging is associated with numerous alterations at the cellular and molecular levels, such as cell senescence, telomere shortening, stem cell exhaustion, and gene expression changes. Epigenomic remodeling is also changed during the lifespan, suggesting that changes in DNA methylation form a vital element of the aging process.

Initial studies reported that there are approximately 45,000 CpG islands per haploid genome in humans and 37,000 in the mouse (41). Approximately half of the mammalian gene promoters are linked with one or more CpG islands and are often free of methylation (42–44). The examination of CpG islands in genomic DNA of human blood, muscle, and spleen showed differential methylation at HOXC gene cluster, whereas the HOXC gene cluster is not differentially methylated in brain tissue. In addition, the level of CpG islands methylation in the brain is lower than the blood, spleen, and muscle (45), which shows certain gene clusters exhibit tissue specific methylation pattern.

The changes in DNA methylation in blood have been reflected in brain regions and other tissues. In general, most of the tissues follow the pattern of rapid changes in DNA methylation in early life followed by a gradual decrease later in life. The analysis of human postmortem brain from adult subjects of different ages has led to the identification of such changes. The analysis of CpG methylation in the human prefrontal cortex (PFC) of fetal and elder samples with a focus on 50 promoter regions showed that both sex and age play important roles in DNA methylation at CpG islands on the X chromosome. Importantly, NNAT (neuronatin) expression in the PFC development drops significantly, as it progresses from the fetal to adult stage whereas DNA methylation showed the reverse pattern. Genes involved in schizophrenia and autism (DRD2, NOS1, NRXN1, and SOX10) showed active age-relevant methylation variation during development from fetal to postnatal life although the study was unable to differentiate between methyl and 5-hmC which are abundantly present in the brain (46). The chronological age measures the time passed since birth whereas biological age measures the biological state of an individual. Biological age is loosely defined and used to estimate tissue and organ functional decline, risk of disease linked with age, morbidity, and mortality. Biological age is also termed as physiological age, organismal age or phenotypic age. The biological aging of the same tissues can vary across individuals with the same chronological age. The DNA methylation analysis studies involving various regions of the brain at different ages demonstrate a correlation with chronological age. The examination of the DNA methylation in 387 human brain regions aged from 1 to 102 years revealed that DNA methylation sites (such as PIPOX, DPP8, RHBDD1, FLJ21839, PTGER3 genes) are highly associated with chronological age (47). The above studies are also supported by the finding that alterations in DNA methylation at clusters of CpG sites across multiple tissues including blood and brain are usually related to aging. The DNA methylation patterns of blood mimic the brain during aging (48). Previous reports showed a global decline in DNA methylation, whereas site-specific examination depicted a higher variability in methylation levels in blood cells with aging. These studies also suggest that the loss of regulation of maintenance of DNA methylation occurs over the years. Recent genome-wide investigations in newborns and centenarians demonstrate a more specific pattern; the majority of intergenic CpG sites had a hypomethylation mark, whereas most of the CpG islands remain hypermethylated with aging (49).

The application of machine learning methods to predict biological age based on site-specific DNA methylation alteration has led to the proposal of the term “epigenetic clock” (50, 51). The epigenetic clock predicts the age of human cells, tissues, and organs across individuals based on methylation at specific CpG sites (52). The epigenetic clock predicts biological age more efficiently than chronological age. Hannum’s clock based on methylation at 71 CpGs was analyzed in adult human whole blood to determine the biological age. The Horvath’s clock is based on methylation status at 353 CpGs tested in various sources of cells, tissues, and organs across the lifespan. The age-associated methylation of CpGs profiled in blood, kidney, and skeletal muscle samples hold also true in the brain. Interestingly, CpGs linked with tissue-specific gene expression are hidden from common methylation changes with age (53). The methylation levels at CpG sites of MLH1, TP53, somatostatin (SST), KLF14, methyl-CpG binding domain protein 4 (MBD4), NEK4, JAKMIP3, STEAP2, and ELOVL2 have been reported to be significantly connected with the chronological age of individuals, proving the occurrence of aging-related methylation changes in an expected pattern (51). In addition, genes with promoter hypermethylation have been reported to be enriched in Polycomb group targets (50). Most recently, Levine et al. (2018) analyzed DNA methylation data from human blood against a multi-system estimation of biological age, or phenotypic age, to set up an epigenetic clock referred to as DNAm (DNA methylation) PhenoAge comprising of 513 CpG sites (54). The measures of phenotypic age included 10 clinical markers of tissue function, immune function, and chronological age. DNAm PhenoAge is more efficient than the earlier epigenetic clocks of DNAm age predictors for expecting occurrence of disease and death. In summary, DNAm PhenoAge depending on DNAm status represents organismal age and functional ability of many tissues and organ systems, apart from what could be described by chronological time. In spite of that, both Hannum’s clock and DNAm PhenoAge are applicable to adult blood samples but exhibit an inability in estimating accurate age in children and in non-blood tissues (54). Several biological functions common to genes with described epigenetic alterations in aging are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

GO analysis using the Enrichr tool for the CpG genes obtained from Horvath’s clock, Hannum’s clock, and DNAm PhenoAge with described methylation alterations in aging

| Gene Ontology | GO Terms | P-value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Process | Negative regulation of programmed cell death | 3.0E-04 | DDR1;LTK;FOXE3;PRKAA2;GLO1;FHL2;PSEN1;HSP90B1;CASP3;RPS6KA1;EPHB1;NGFR; CDSN; WFS1;MGMT;RHBDD1;BNIP3;INSR;PLK2;PLK1;FZD9;NR1H4;DHCR24;MMP9; HYPK;GREM1; SUPV3L1; SFRP1;WT1;DDAH2;CAT;IL6ST;FXN;BIRC2 |

| Unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic process | 4.72E-04 | ALOX5;ALOX5AP;SCD5;DEGS1;ALOX12 | |

| Endocrine system development | 9.5E-04 | WT1;SIX1;GLI2;WNT4;DKK3;STRA6 | |

| Adrenal gland development | 9.5E-04 | WT1;WNT4;DKK3;STRA6 | |

| N-acetylneuraminate metabolic process | 9.54E-04 | AMDHD2;NPL;ST3GAL1;GNE | |

| Metanephric mesenchyme development | 1.4E-03 | WT1;BASP1;SIX1;WNT4 | |

| Heart development | 2.5E-03 | MYBPC3;CXADR;INSR;PDGFB;CACYBP;TBX5;GLI2;SCUBE1;WT1;FLRT3;MYL2;PLCE1; ZFPM1; DAND5;STRA6 | |

| Lipoxin biosynthetic process | 2.6E-03 | ALOX5;ALOX5AP;ALOX12 | |

| Response to fatty acid | 2.6E-03 | GLDC;PDK4;UCP1;NR1H4 | |

| Cell morphogenesis | 4.6E-03 | GREM1;CYFIP1;RELN;CAPZB;CDH1;RHOH;NOX4;CDH9 | |

| Molecular Function | G-protein coupled receptor binding | 8.2E-04 | CALCA;PDCD6IP;USP20;WNT5B;WNT8B;ADM;REEP1;POMC;SFRP1;UCN2;BAMBI;PENK; CCRL2;GNAS;WNT4 |

| Protein homodimerization activity | 9.5E-04 | GLDC;HM13;ODC1;NPR3;CAMK2A;PDGFB;CIB2;PVR;CDH9;SYNE1;CD79A;CREB3L3; FLRT3;CDH1;OXCT1;SNX9;ANXA9;MAP3K5;S100A10;PDCD6IP;SLC30A8;CDSN;RBPMS; S100A1;BNIP3;ZBTB16; EPHX2;CRTAM;FZD9;CIDEA;NAGA;CACYBP;NR2F2;SNF8;SDCBP2; GREM1;SUPV3L1;ALDH1A3; CENPF;SP1;APOC2CAT;S100A6;TLR9;CHMP4C;MAP3K10; IL6ST | |

| Tropomyosin binding | 3.4E-03 | CALD1;TMOD3;S100A6;LMOD1 | |

| U1 snRNA binding | 4.0E-03 | RBPMS;SNRPB2;PRPF8 | |

| Ether hydrolase activity | 5.8E-03 | EPHX2;EPHX3;ALOX12 | |

| Aspartic-type endopeptidase activity | 1.4E-02 | BACE1;CASP3;HM13;PSEN1 | |

| Sialyltransferase activity | 1.4E-02 | ST8SIA2;ST3GAL4;ST6GALNAC4;ST3GAL1 | |

| RNA stem-loop binding | 2.1E-02 | RBPMS;SNRPB2;LARP6 | |

| Retinoid binding | 2.2E-02 | RXRA;CRABP2;CRABP1;NR2F2 | |

| Frizzled binding | 2.4E-02 | SFRP1;WNT5B;BAMBI;WNT8B;WNT4 |

GO, gene ontology; The significant terms with multiple genes at the biological process and molecular function characterization levels are shown. P-values show the statistical significance of the enrichment of gene ontology terms with analyzed genes.

Epigenetic drift refers to a large number of CpG methylation changes that act as a biomarker for age within an individual but are not uniform across the individuals. Epigenetic drift has been connected to a multitude of age-related status that includes cell type or organ, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, gender, body mass index (BMI), lifestyle, and demographic variables (55). The 30 anatomic tissues of super centenarians (people who have attained the age of 110 years or older) showed that cerebellum ages more slowly than other parts of the human body. Interestingly, the genetic and transcriptional studies concluded that RNA helicase genes highly expressed in the cerebellum slows the aging rate of supercentenarians (56). Methylation data from human cortex predicted age-related neurodegeneration. Further, accelerated epigenetic age has been reported as heritable and to exhibit a significant association with amyloid load, diffuse plaques, and decline in working memory (57).

Davies et al. (2012) employed methylated DNA immunoprecipitation along with ultra-deep sequencing (Me-DIP) to analyse the methylome in human samples collected from various brain regions and blood. Interestingly, the study revealed that tissue specific-differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were prominently enriched near genes involved in functionally relevant neurobiological pathways, including BDNF, BMP4, CACNA1A, CACA1AF, EOMES, NGFR, NUMBL, PCDH9, SLIT1, SLITRK1, and SHANK3. Although, the number of individual samples analyzed was relatively small and all the samples were received from donors older than 75 years, which may not fully depict patterns of DNA methylation observed earlier in life (58). Spiers et al. (2015) analyzed the genome-wide patterns of methylation level in 179 human fetal brain samples from 23 to 184 days post-conception and identified that the status of DNA methylation is significant changed during fetal brain development at > 7% of sites, with an enrichment of loci becoming hypomethylated with fetal age (59). The analysis showed that comethylated loci (methylated genes shared among the phenotypic traits such as days post-conception (DPC) and sex) linked with fetal age are interestingly enriched with genes having a role in neurodevelopmental processes. The developmentally differentially methylated positions (dDMPs) showed enrichment within the gene body, and these sites displayed DNA hypomethylation with age. Interestingly, DNA methylation at the gene body often enhanced the gene expression. Most of the gender variations in the brain methylome exhibited at an early stage in fetal development and was stable across the lifetime. The researchers identified 61 sites indicating gender-specific DNA methylation trajectories during brain development. Notably, RBPJ involved in neurogenesis and neuronal maturation was identified as the top-ranked gene. Fetal brain dDMPs are located in the vicinity of genetic loci of autism-associated genes (i.e. NRXN1 and SHANK) and schizophrenia-associated gene like PPP1R16B (59).

Seminal studies conducted by Lister et al. (2013) concluded that DNA methylation plays a vital role in the development and maturation of neuron in mammalian developing and adult mammalian brain (60). The researchers analyzed the DNA methylation dynamics at ~1 billion cytosines in the genome by genome-wide single-base resolution profiling and 5-hmC signature by TAB-Seq in the frontal cortex of humans and mice at key developmental stages. They found that mCH (mCH/CH, H = A, C, or T) methylation level accumulation initially mimics the elevation in synapse density in human middle frontal gyrus regions and further continues to rise from the age of 5 and 16 years during which synaptic pruning occurs. A higher ratio of mCH is shown in neurons in comparison to glial cells. However, ~80% percentage methylation has been detected at the CG site of the neurons compared to the CH site (~2–6%). Higher levels of mCH modification was detected at X-chromosomal genes that escape X-chromosome inactivation in females. In addition, 5-hMC marks enriched at neuronal and astrocyte gene bodies at the fetal stage are hyper-hydroxymethylated at adult stage and guide the development of the frontal cortex (60).

In summary, differentially methylated genes identified from three epigenetic clocks were associated with various biological processes and molecular functions resulting in control of the aging process (Table 1). It is hypothesized that further experimental investigations in addition to the present statistical model and analysis might possibly formulate ways to retard biological aging by focusing on the age-linked DNA methylation levels.

DNA METHYLATION ALTERATIONS IN NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

In the last decade, the importance of DNA methylation in the functioning of the central nervous system has gained immense attention (61–68). Numerous studies have investigated patterns of DNA methylation at various cellular stages such as stem cells and terminally differentiated cells like neurons and glia. A few research groups have focused their attention on pathological stages of neurodegenerative diseases. In the subsequent sections, we aim to discuss recent findings of DNA methylomes in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, ALS/FTD, Huntington Disease, and Multiple sclerosis.

DNA methylome in Alzheimer’s disease

Presently, there are 46.8 million dementia cases worldwide and the number is expected to rise to 74.7 million in 2030. Health care burden of dementia in 2015 exceeded $818 billion (USD) and this figure is projected to reach $2 trillion by 2030. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most familiar cause of dementia, which is characterized by the degeneration of neurons. The presence of extraneural amyloid plaque (Aβ) and intraneural neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) are the hallmarks of the disease (69). To date, around 270 gene mutations have been identified as the cause of familial AD that includes APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes. The gene mutations account only for ~5% of all AD cases, therefore it is hypothesized that the study of epigenetic changes induced by environmental factors might provide an explanation for remaining cases (70). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified almost 20 genetic loci linked with increased susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) (71). Several studies also support the linear model of amyloid hypothesis which postulates that Aβ deposition initiated neurotoxicity is mediated by hyperphosphorylated Tau resulting in dementia (72). Despite the three decades of focus on β-Amyloid cascade hypothesis, there exists huge evidence, which implies that this theory alone is insufficient to explain the pathogenesis of AD. To find the primary cause of the disease, the methylation changes in the brain needs to be unified with the cellular signaling network. It is necessitated to identify the methylation changes in the brain that control the initiation and progression of neurodegeneration in connection with diverse cellular signaling pathways. Herein, we describe the key aspects of several human brain methylome studies conducted in AD patients.

Simultaneous studies published by two independent groups have provided the first complete DNA methylome of AD. These two independent studies found four unique hypermethylated genes i.e. ANK1, RHBDF2, RPL13, and CDH23 (67, 68). Jager et al. (2014), demonstrated a significant correlation between 71 of the 415,848 investigated CpGs with a load of AD pathology in autopsied brains (67). In addition, the researchers linked six of the hypermethylated genes (ANK1, DIP2A, RHBDF2, RPL13, SERPINF1, and SERPINF2) to AD susceptibility network and stated implication of DNA methylation alterations in the onset of AD. The CpGs such as cg22883290 in the BIN1 locus and cg02308560 in the ABCA7 locus linked with AD is independent of their associated SNPs rs744373 (BIN1) and rs3764650 (ABCA7) respectively. Lunnon et al. (2014), examined AD methylome of multiple tissues from four different human post-mortem brain cohorts (68). The researchers found a DMR in the ANK1 gene that was associated with early effects of Aβ or NFT pathology in the entorhinal cortex but not in the cerebellum, a region largely resistant to neurodegeneration in AD. Technically, the two-way strategy was applied to overcome the false positives: the elimination of probes prone to be affected by common SNPs and the statistical filtering of maximal sample outliers in individual probe data that are commonly caused by rare SNPs. Although the previously mentioned DNA methylomes have revealed interesting conclusions, the reported studies have few limitations such as the specific cell-type buildup was not considered while examining specific cortical areas and the studies lacked information about representation of distinct aspects of brain substructure based on the differentiation of the neurons and glial cells. Both the studies used Illumina 450K array for methylation. The 450K array consists exclusively of CpGs associated with disease candidate genes, which only detects ~2% of the CpGs found in the human genome and the array lacks efficiency in discriminating between CpG and 5-hMC, which have conflicting effects on gene expression (73).

To address these limitations, Sanchez-Mut et al. (2017), studied single-nucleotide resolution by applying WGBS on the gray matter from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex Brodmann area 9 of normal and neurodegenerative disorders cases (74). Previous studies in AD identified four common hypermethylated genes (ANK1, RHBDF2, RPL13 and CDH23) (67, 68). Sanchez-Mut et al. confirmed these findings for ANK1 and RHBDF2 in AD, and for ANK1 in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) at single nucleotide resolution. It was also reported that AD, DLB, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Down’s syndrome (DS) have common aberrant DNA methylation profile marked by the presence of the abnormal CpG methylation status of a group of shared genes involved in various signaling pathways. It is hypothesized that the DNA methylome studies on neurodegenerative disorders might provide insights about common features exhibited at cell biology and clinical stages from DNA methylation perspective. As half of the AD cases have α-synuclein inclusions, PD and DLB brains revealed the presence of Aβ plaques and NFT (75); α-synuclein inclusions were frequently reported in DS (74, 76).

In support of prior AD methylome studies, Yu et al. (2015) examined the relationship between brain DNA methylation in 28 known AD loci and the molecular markers of AD, Aβ or NFT density. Interestingly, the researchers found that 60.4% of AD cases showed a positive association between DNA methylation in SORL1, ABCA7, HLA-DRB5, SLC24A4, and BIN1 gene locus and pathological AD (66). Since SNPs are known to affect methylation quantitative trait loci and expression quantitative trait loci, both cis and trans, in human brain, further researches are needed to corroborate the finding that disturbances in DNA methylation along with SNPs play crucial roles in the pathological process of AD (Fig. 1B) (77, 78).

To further explore whether methylation at CpG sites located on AD susceptibility gene regions is associated with Aβ burden, the study involving 740 brain samples by Illumina 450K array reported that the observed methylation changes are independent of AD-associated genetic variants in BIN1, CLU, MS4A6A, ABCA7, CD2AP, and APOE loci. The higher methylation of CpGs in ABCA7, CD2AP, CLU, and MS4A6A loci were stated to be associated with Aβ plaque (79).

Studies investigating the role of DNA methylome in neurodegenerative diseases like AD are still at the commencement stage. Further biochemical and in vivo assay will help in understanding the function of aberrantly methylated genes concerning origin and advance of AD. In addition, futuristic studies should consider the effect of aberrant DMR on chromatin structure that is accountable for AD pathogenesis. Finally, it is a big question to answer whether reshaping the epigenome can yield the development of AD in the animal model.

In conclusion, many methylome studies in AD brain have demonstrated that DNA methylation changes at a few common gene loci play a critical role. These studies are encouraging since DMR in ANK1, RHBDF2, Bin1, and ABCA7 loci are linked with the formation of Aβ plaque. Identification of the implications of DNA methylation changes at identified CpG loci on cellular signaling pathways needs to be investigated in the future.

Parkinson’s disease (PD)

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is identified as the most frequently occurring neurodegenerative disorder after AD. Approximately, 7 to 10 million people worldwide are predicted to be affected by PD. Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed by the early symptoms of bradykinesia, muscular rigidity, rest tremor, postural and gait impairment, and late symptoms include postural instability, freezing of gait, falls, dysphagia, and speech defects (80). Pathologically, PD is characterized by the formation of intraneuronal inclusions called Lewy bodies, composed of α-synuclein (α-syn), along with degeneration of dopaminergic neurons mainly in the substantia nigra. Familial cases of PD, directly affecting ~15% of all cases have been reported to be caused by mutations in the LRRK2, PARK7, PINK1, PRKN, or SNCA genes (81). PD develops from a complex interaction of genetics and environment. PD is now considered as a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder that initiates years before the appearance of symptoms. DNA methylation patterns are modified by environmental factors and can be inherited through cell division. Possibly, environmental factors may cause alterations in DNA methylation patterns, which determine the individual genetic susceptibility to PD. In addition to the acquired mutations in one gene or a group of genes involved in the progress of several disorders, DNA methylation alterations have been found to contribute essentially to their development. Therefore, it is not surprising to note that deregulation of DNA methylation can be critical for the onset of PD.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified several PD risk loci in the cerebellum and frontal cortex of post mortem PD brains, namely PARK16, GPNMB, and STX1B genes that were associated with differential DNA methylation (82). To investigate DNA methylation alterations in PD, an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) was performed. The examination of cortex and putamen regions from PD patients using Illumina 27K array showed hypomethylation of the CYP2E1 gene and up-regulation of mRNA levels of CYP2E1 in PD cortex samples (63). Masliah et al. (2013), examined genome-wide DNA methylation in frontal cortex and blood samples from PD patients (83). The researchers found a unique methylation pattern of genes previously known to be associated with PD. Notably, consistent methylation changes in brain and blood, indicating that blood tissue can mimic DNA methylation changes in the brain, was demonstrated. DNA methylation might be used as a promising biomarker for Parkinson’s disease (83). The meta-analysis of Parkinson’s disease GWAS across 13,708 cases found six new risk loci associated with DNA methylation or mRNA expression. The risk allele (A) at rs199347 on chromosome 7 was linked with an elevated transcription of NUPL2 as well as with hypomethylation. The risk allele (T) at rs823118 on chromosome 1 was linked with lower expression of NUCKS1 and higher transcription of RAB7L1 as well as with hypermethylation at PM20D1 in both frontal cortex and cerebellar regions. The authors suggest the need for future experimental and deep sequencing studies to understand the complex nature of this region (84). Importantly, the brain methylation alterations in a group of genes in PD brain might provide a novel biomarker as well as a therapeutic target for small molecule discovery and development for PD.

In summary, since there exists only a few human brain methylome studies in PD and differentially methylated genes commonly found among different studies are not many, future studies must focus on the association of DNA methylation variation with the occurrence of pathological hallmarks of PD.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/fronto temporal dementia (ALS/FTD)

ALS and FTD are two lethal neurodegenerative diseases with an occurrence of 30,000 cases alone in the US leading to comorbidity in about 50% of cases. FTD and ALS are investigated as a part of a common spectrum and share similar neurodegenerative pathways (85). Symptoms of FTD include dementia, commonly portrayed as behavioral, personality, and speech problems caused by degeneration of frontal and temporal cortical neurons. ALS patients exhibit reduced control over voluntary movements caused by progressive degeneration of lower motor neurons and loss of upper motor neurons resulting in muscle wasting. FTD is the second most prevalent dementia after AD. The finding of numerous mutations in two dozen genes explained the involvement of several pathways in the development of ALS/FTD, while the pinpointing of hexanucleotide repeat expansion (HRE) in C9orf72 accounted for up to 80% of familial ALS-FTD (86).

The HRE mutation in C9orf72 is hypothesized as the cause of disease pathogenesis involving three mechanisms: 1) The HRE mutation in C9orf72 may cause a reduction in the expression of its mRNA in the allele harboring hexanucleotide repeat (haploinsufficiency); 2) RNA foci with transcribed G4C2 repeats may cause sequestration of RNA-binding protein(s); and 3) RANT (repeat-associated non-ATG mediated translation) aggregates may lead to accumulation of toxic RNA and protein pathologies. Aberrant effects of unstable DNA elements targeting the genome have been reported to be neutralized by suppression of the incorrect gene expression via CpG methylation. C9orf72 promoter is hypermethylated in 30% of mutation carriers in cis with the HRE carriers resulting in decreased accumulation of RNA foci and RANT aggregates in human brains. These results suggest that hypermethylation of C9orf72 promoter inhibits downstream consequences linked with the HRE (87). Multivariate regression model studies also stated that C9orf72 promoter methylation levels are associated with the following features, 1) they are heritable, 2) are linked with a shorter repeat size, 3) stable across time and tissue types, and 4) linked with extended survival in FTD patients (88, 89).

Recent methylome study carried out in ALS/FTD with few patient samples has potentially demonstrated the beneficial effects of CpG methylation in ALS/FTD. It is believed that further studies with a large number of samples might implicate the association of methylation with other mutated genes in ALS/FTD.

Huntington disease

In western countries, Huntington’s disease (HD) has been reported in 10.6–13.7 person per 100,000 people. The affected individuals display cognitive decline with sleep disturbances, weight loss, and emotional disturbance followed by involuntary movement disorder (Chorea). The disorder can typically manifest between infancy and senescence (90). HD is a progressive autosomal dominant neurological disorder caused by CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion of the huntingtin (HTT) gene. The CAG repeat lengths of ≥ 40 units are translated into polyglutamine strand of the pathogenic HTT protein. Mutant HTT is resistant to protein turnover and highly penetrant resulting in cellular toxicity and neurodegeneration (91). Approximately, 60–70% of the variability in the age of onset identified in HD cases showed an inverse correlation with CAG repeat length. Another ~30% of the variability in the age of onset may be contributed to genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors (92). Therefore, alteration in DNA methylation is considered to affect HTT gene expression by changing the transcription of the HTT promoter.

Adenosine A2A receptor (ADORA2A), a G-protein-coupled receptor is abundantly expressed in basal ganglia, while its expression levels are markedly decreased in HD. Examination of putamen of 10 HD patients showed hypermethylation of CpG islands and decreased 5-hmC in the 5′UTR region of ADORA2A. Thus, hypermethylation of ADORA2A is the molecular mechanism behind the decreased expression of A2AR in HD (93). EWAS (epigenome-wide association study) analyses in the cortex of small HD samples revealed the lowest evidence of alterations in HD-related DNA methylation. However, DNA methylation may be linked with the age of disease onset in HD cortex samples. Intriguingly, the researchers observed a site-specific decrease in the differences in DNA methylation at the HTT proximal promoter specifically at CTCF-binding site; the CTCF site displayed increased occupancy in cortex tissue, which is responsible for cortex-specific HTT expression (92). However, these studies had several limitations; 1) it is possible that HD-relevant DNA methylation alterations are present at sites beyond the analyzed sites, 2) as CAG repeat expansion leads to HD mutation; it is possible that the expanded HD CAG repeats in human cortex will be influenced by aberrant non-CpG methylation, and 3) a small number of diseased samples.

It is impulsive to reach a conclusion on the role of DNA methylation in HD based on the findings of a couple of studies. Well-designed methylome studies in HD cases might yield novel therapeutic target for developing a treatment strategy for HD.

Multiple sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune, chronic inflammatory, and demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. MS affects approximately 2.5 million people worldwide, especially young adults and women. The physical symptoms include fatigue, mobility challenges, bladder or bowel problems, tremor, vision problems, problems with coordination, and cognitive difficulties (94). MS is characterized by the presence of lesions in the CNS with focal destruction of myelin, which is considered as a pathological hallmark of MS. However, the surrounding normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) shows the abnormalities such as edema, axonal damage, and reactive gliosis which contributes to progressive brain atrophy (95). GWAS have identified MS susceptibility loci; however, their functional importance related to MS pathogenesis is still unexplained. The factors such as the occurrence of SNPs in monozygotic twins is relatively low. High susceptibility of women, geographic risk of developing MS, and the influence of migration on disease onset suggest that the epigenetic changes play important roles in the pathogenesis of MS.

Earlier reports revealed increased citrullination of histone H3 and acetyl-H3 in NAWM of MS brain (96, 97) and mentioned the prospect that DNA methylation alterations might regulate gene expression. Interestingly, NAWM derived from MS brain analysis showed hypermethylation of oligodendrocyte and neuronal function-related genes BCL2L2, HAGHL, and NDRG1 and reduced transcript levels. In addition, hypomethylation was observed in cysteine proteases such as LGMN and CTSZ along with an increase in their transcript levels (98).

CONCLUSION

This review presents a comprehensive summary of the human brain DNA methylome during aging and neurological diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases are multifactorial and associated with age, environmental, and genetic factors. The human DNA brain methylome studies have opened a new door for understanding the CNS diseases. The recent development of techniques assists in finding accurate levels of different DNA methylation modification throughout the genome. The reported studies suggest the followings. 1) The DNA methylation alterations happen initially in the disease process, 2) DNA methylation alterations alone or in combination with disease-specific SNPs can enhance disease susceptibility (Fig. 1C), and 3) DNA methylation changes can be correlated with misfolded proteins of the neurodegenerative diseases in specific brain regions. The key features of human DNA methylome studies are discussed in Table 2. The identified gene loci may potentially help in understanding the cause and early diagnosis of CNS diseases, and development of small molecules for treatment. Although, the DNA methylome studies in neurodegenerative diseases are in their beginning stage; they are providing a novel path towards new research direction. The in vitro and in vivo models of already identified CpG loci in neurodegenerative diseases are hypothesized to support the investigations of biochemical and functional aspects. The application of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons, genome editing techniques, and humanized animal models in future studies are proposed to help in further deepening our knowledge of these diseases.

Table 2.

Overview of human brain DNA methylome studies involving neurodegenerative diseases

| Disease | No of DMR | Examples of nearest genes | Brain Region | Sample Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 71 | ANK1, CDH23, DIP2A, RHBDF2, RPL13, SERPINF1 and SERPINF2 | Entorhinal, temporal, and prefrontal cortex | 708 | 67 |

| 100 | ANK1, MIR486, PCBD1, SLC15A4, SIRT6, MEST, MLST8, ZNF512, TMX4 | Entorhinalcortex, superior temporal gyrus and prefrontal cortex | 104 | 68 | |

| 5 | SORL1, ABCA7, HLA-DRB5, SLC24A4, BIN1 | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 740 | 66 | |

| 6 | BIN1, CLU, MS4A6A, ABCA7, CD2AP, and APOE | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 740 | 79 | |

| Parkinson’s Disease | PARK16, GPNMB, STX1B, STBD1 | Frontal cortex and Cerebellum | 292 | 82 | |

| CYP2E1, Catalase, LOC148811, LOC84245 | Putamen and cortex | 6 | 63 | ||

| 6 | FLJ32569, NOTCH4, SLC44A4, GPNMB, KIAA1267, STX1B2, SLC4A11 | Frontal cortex and cerebellar regions | 292 | 84 | |

| ALS/FTD | C9orf72 | Cerebellum | 4 | 87 | |

| Huntington Disease | ADORA2A | Putamen | 10 | 93 | |

| Methylated binding site in the HTT proximal promoter for the CTCF transcription factor | Cortex | 10 | 92 | ||

| Multiple Scelerosis | Hypomethylated: 495 | AKAP6, CX3CL1, GATA3, LRRC27, MBL2, ARHGAP22, CTSZ, MGAT, BCL2L2, SBF1, | Normal appearing white matter | 28 | 98 |

| Hypermethylated: 439 | SLC47A2, CRY2, NDRG |

DMR, Differentially Methylated Regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the 2019 Research Fund of the University of Seoul.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wyatt G. Recognition and estimation of 5-methylcytosine in nucleic acids. Biochem J. 1951;48:581. doi: 10.1042/bj0480581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotchkiss RD. The quantitative separation of purines, pyrimidines, and nucleosides by paper chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1948;175:315–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird AP. DNA methylation and the frequency of CpG in animal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:1499–1504. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Illingworth RS, Gruenewald-Schneider U, Webb S, et al. Orphan CpG islands identify numerous conserved promoters in the mammalian genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladd-Acosta C, Pevsner J, Sabunciyan S, et al. DNA methylation signatures within the human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1304–1315. doi: 10.1086/524110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegmund KD, Connor CM, Campan M, et al. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS One. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyes J, Bird A. Repression of genes by DNA methylation depends on CpG density and promoter strength: evidence for involvement of a methyl-CpG binding protein. EMBO J. 1992;11:327–333. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh CL. Dependence of transcriptional repression on CpG methylation density. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5487–5494. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.8.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent L, Wong E, Li G, et al. Dynamic changes in the human methylome during differentiation. Genome Res. 2010;20:320–331. doi: 10.1101/gr.101907.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauch TA, Wu X, Zhong X, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP. A human B cell methylome at 100– base pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:671–678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812399106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, et al. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domcke S, Bardet AF, Ginno PA, Hartl D, Burger L, Schübeler D. Competition between DNA methylation and transcription factors determines binding of NRF1. Nature. 2015;528:575. doi: 10.1038/nature16462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gartler SM, Riggs AD. Mammalian X-chromosome inactivation. Annu Rev Genet. 1983;17:155–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.17.120183.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reik W, Collick A, Norris ML, Barton SC, Surani MA. Genomic imprinting determines methylation of parental alleles in transgenic mice. Nature. 1987;328:248. doi: 10.1038/328248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swain JL, Stewart TA, Leder P. Parental legacy determines methylation and expression of an autosomal transgene: a molecular mechanism for parental imprinting. Cell. 1987;50:719–727. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day JJ, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation and memory formation. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1319. doi: 10.1038/nn.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Counts JL, Goodman JI. Alterations in DNA methylation may play a variety of roles in carcinogenesis. Cell. 1995;83:13–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jähner D, Stuhlmann H, Stewart CL, et al. De novo methylation and expression of retroviral genomes during mouse embryogenesis. Nature. 1982;298:623. doi: 10.1038/298623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh CP, Chaillet JR, Bestor TH. Transcription of IAP endogenous retroviruses is constrained by cytosine methylation. Nat Genet. 1998;20:116. doi: 10.1038/2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermann A, Gowher H, Jeltsch A. Biochemistry and biology of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2571–2587. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruenbaum Y, Cedar H, Razin A. Substrate and sequence specificity of a eukaryotic DNA methylase. Nature. 1982;295:620. doi: 10.1038/295620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:215. doi: 10.1038/nn.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng J, Zhou Y, Campbell SL, et al. Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a maintain DNA methylation and regulate synaptic function in adult forebrain neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:423. doi: 10.1038/nn.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veldic M, Caruncho H, Liu W, et al. DNA-methyltransferase 1 mRNA is selectively overexpressed in telencephalic GABAergic interneurons of schizophrenia brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:348–353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637013100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu M, Hon GC, Szulwach KE, et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell. 2012;149:1368–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Lu X, Lu J, et al. Thymine DNA glycosylase specifically recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine-modified DNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:328. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rai K, Huggins IJ, James SR, Karpf AR, Jones DA, Cairns BR. DNA demethylation in zebrafish involves the coupling of a deaminase, a glycosylase, and gadd45. Cell. 2008;135:1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhutani N, Brady JJ, Damian M, Sacco A, Corbel SY, Blau HM. Reprogramming towards pluripotency requires AID-dependent DNA demethylation. Nature. 2010;463:1042. doi: 10.1038/nature08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhutani N, Burns DM, Blau HM. DNA demethylation dynamics. Cell. 2011;146:866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santiago M, Antunes C, Guedes M, Sousa N, Marques CJ. TET enzymes and DNA hydroxymethylation in neural development and function—how critical are they? Genomics. 2014;104:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito S, D’alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawlaty MM, Breiling A, Le T, et al. Combined deficiency of Tet1 and Tet2 causes epigenetic abnormalities but is compatible with postnatal development. Dev Cell. 2013;24:310–323. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyward FD, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation in memory formation: emerging insights. Neuroscientist. 2015;21:475–489. doi: 10.1177/1073858415579635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antequera F, Bird A. Number of CpG islands and genes in human and mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11995–11999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Consortium IHGS. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ioshikhes IP, Zhang MQ. Large-scale human promoter mapping using CpG islands. Nat Genet. 2000;26:61. doi: 10.1038/79189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Illingworth R, Kerr A, DeSousa D, et al. A novel CpG island set identifies tissue-specific methylation at developmental gene loci. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Numata S, Ye T, Hyde TM, et al. DNA methylation signatures in development and aging of the human prefrontal cortex. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernandez DG, Nalls MA, Gibbs JR, et al. Distinct DNA methylation changes highly correlated with chronological age in the human brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1164–1172. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horvath S, Zhang Y, Langfelder P, et al. Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R97. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyn H, Li N, Ferreira HJ, et al. Distinct DNA methylomes of newborns and centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10522–10527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14:3156. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell. 2013;49:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung SE, Shin KJ, Lee HY. DNA methylation-based age prediction from various tissues and body fluids. BMB Rep. 2017;50:546–553. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.11.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Day K, Waite LL, Thalacker-Mercer A, et al. Differential DNA methylation with age displays both common and dynamic features across human tissues that are influenced by CpG landscape. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-9-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10:573. doi: 10.18632/aging.101414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:371. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horvath S, Mah V, Lu AT, et al. The cerebellum ages slowly according to the epigenetic clock. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:294. doi: 10.18632/aging.100742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levine ME, Lu AT, Bennett DA, Horvath S. Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:1198. doi: 10.18632/aging.100864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spiers H, Hannon E, Schalkwyk LC, et al. Methylomic trajectories across human fetal brain development. Genome Res. 2015;25:338–352. doi: 10.1101/gr.180273.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science. 2013;341:1237905. doi: 10.1126/science.1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bakulski KM, Dolinoy DC, Sartor MA, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation differences between late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal controls in human frontal cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:571–588. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rao J, Keleshian V, Klein S, Rapoport S. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer’s disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e132. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaut O, Schmitt I, Wüllner U. Genome-scale methylation analysis of Parkinson’s disease patients’ brains reveals DNA hypomethylation and increased mRNA expression of cytochrome P450 2E1. Neurogenetics. 2012;13:87–91. doi: 10.1007/s10048-011-0308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanchez-Mut JV, Aso E, Panayotis N, et al. DNA methylation map of mouse and human brain identifies target genes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2013;136:3018–3027. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanchez-Mut JV, Aso E, Heyn H, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the phosphatase DUSP22 mediates PKA-dependent TAU phosphorylation and CREB activation in Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus. 2014;24:363–368. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu L, Chibnik LB, Srivastava GP, et al. Association of Brain DNA methylation in SORL1, ABCA7, HLA-DRB5, SLC24A4, and BIN1 with pathological diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:15–24. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1156. doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lunnon K, Smith R, Hannon E, et al. Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1164. doi: 10.1038/nn.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bae JR, Kim SH. Synapses in neurodegenerative diseases. BMB Rep. 2017;50:237–246. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.5.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delgado-Morales R, Esteller M. Opening up the DNA methylome of dementia. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:485. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giri M, Zhang M, Lü Y. Genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease: an overview and current status. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:665. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S105769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cho S, Ahn E, An H, et al. Association of miR-938G> A polymorphisms with primary ovarian insufficiency (POI)-related gene expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1255. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lord J, Cruchaga C. The epigenetic landscape of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1138. doi: 10.1038/nn.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanchez-Mut JV, Heyn H, Vidal E, et al. Human DNA methylomes of neurodegenerative diseases show common epigenomic patterns. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e718. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galpern WR, Lang AE. Interface between tauopathies and synucleinopathies: a tale of two proteins. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:449–458. doi: 10.1002/ana.20819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lippa CF, Schmidt ML, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Antibodies to α-synuclein detect Lewy bodies in many Down’s syndrome brains with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:353–357. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<353::AID-ANA11>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Eijk KR, de Jong S, Boks MP, et al. Genetic analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression levels in whole blood of healthy human subjects. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:636. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gibbs JR, van der Brug MP, Hernandez DG, et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chibnik LB, Yu L, Eaton ML, et al. Alzheimer’s loci: epigenetic associations and interaction with genetic factors. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2:636–647. doi: 10.1002/acn3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet. 2015;386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trinh J, Farrer M. Advances in the genetics of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:445. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Consortium IPsDG and 2 WTCCC. A two-stage meta-analysis identifies several new loci for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Masliah E, Dumaop W, Galasko D, Desplats P. Distinctive patterns of DNA methylation associated with Parkinson disease: identification of concordant epigenetic changes in brain and peripheral blood leukocytes. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1030–1038. doi: 10.4161/epi.25865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nalls MA, Pankratz N, Lill CM, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:989. doi: 10.1038/ng.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Belzil VV, Katzman RB, Petrucelli L. ALS and FTD: an epigenetic perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:487–502. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1587-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu EY, Russ J, Wu K, et al. C9orf72 hypermethylation protects against repeat expansion-associated pathology in ALS/FTD. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:525–541. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1286-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Russ J, Liu EY, Wu K, et al. Hypermethylation of repeat expanded C9orf72 is a clinical and molecular disease modifier. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1365-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xi Z, Rainero I, Rubino E, et al. Hypermethylation of the CpG-island near the C9orf72 G4C2-repeat expansion in FTLD patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5630–5637. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McColgan P, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:24–34. doi: 10.1111/ene.13413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bates GP, Dorsey R, Gusella JF, et al. Huntington disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15005. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Souza RA, Islam SA, McEwen LM, et al. DNA methylation profiling in human Huntington’s disease brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2013–2030. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Villar-Menéndez I, Blanch M, Tyebji S, et al. Increased 5-methylcytosine and decreased 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels are associated with reduced striatal A 2A R levels in Huntington’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2013;15:295–309. doi: 10.1007/s12017-013-8219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Faguy K. Multiple sclerosis: An update. Radiol Technol. 2016;87:529–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lindberg RL, De Groot CJ, Certa U, et al. Multiple sclerosis as a generalized CNS disease—comparative microarray analysis of normal appearing white matter and lesions in secondary progressive MS. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;152:154–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pedre X, Mastronardi F, Bruck W, López-Rodas G, Kuhlmann T, Casaccia P. Changed histone acetylation patterns in normal-appearing white matter and early multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3435–3445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4507-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mastronardi FG, Wood DD, Mei J, et al. Increased citrullination of histone H3 in multiple sclerosis brain and animal models of demyelination: a role for tumor necrosis factor-induced peptidylarginine deiminase 4 translocation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11387–11396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3349-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huynh JL, Garg P, Thin TH, et al. Epigenome-wide differences in pathology-free regions of multiple sclerosis–affected brains. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:121. doi: 10.1038/nn.3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]