Abstract

PURPOSE

Practice transformation in primary care is a movement toward data-driven redesign of care, patient-centered care delivery, and practitioner activation. A critical requirement for achieving practice transformation is availability of tools to engage practices.

METHODS

A total of 48 practices with 109 practice sites participate in the Garden Practice Transformation Network in Maryland (GPTN-Maryland) to work together toward practice transformation and readiness for the Quality Payment Program implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Practice-specific data are collected in GPTN-Maryland by practices themselves and by practice transformation coaches, and are provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. These data are overwhelming to practices when presented piecemeal or together, a barrier to practices taking action to ensure progress on the transformation spectrum. The GPTN-Maryland team therefore created a practice transformation analytics dashboard as a tool to present data that are actionable in care redesign.

RESULTS

When practices reviewed their data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services using the dashboard, they were often seeing, for the first time, cost data on their patients, trends in their key performance indicator data, and their practice transformation phase. Overall, 72% of practices found the dashboard engaging, and 48% found the data as presented to be actionable.

CONCLUSIONS

The practice transformation analytics dashboard encourages practices to advance in practice transformation and improvement of patient care delivery. This tool engaged practices in discussions about data, care redesign, and costs of care, and about how to develop sustainable change within their practices. Research is needed to study the impact of the dashboard on costs and quality of care delivery.

Key words: practice transformation; analytics data dashboard; quality indicators, health care; health information technology; value-based care; primary care; practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

Practice transformation is known to improve quality performance, efficiency, connectivity, patient-centered care delivery, and care coordination.1–5 The Garden Practice Transformation Network (GPTN) is working with practices in New Jersey, Maryland, and Puerto Rico as part of the Transforming Clinical Practices Initiative (TCPI).6 The Garden Practice Transformation Network in Maryland (GPTN-Maryland) provides coaching, mentoring, and assistance to 831 practitioners in the state to prepare them for transformation from fee-for-service to value-based payment by 2019. Each participating practice is assigned a practice transformation coach from the GPTN-Maryland team to personalize advice on improvement strategies using the TCPI Change Package to move practices through 5 phases of transformation.6 Practices are offered educational and collaborative opportunities to learn about practice transformation in continuing medical education programs offered by GPTN-Maryland.

This article reports the baseline state of practices at the outset of the GPTN-Maryland program and describes reception of the GPTN prac- tice transformation analytics dashboard as a practice engagement and transformation tool.

BACKGROUND

The GPTN-Maryland program office is located at the University of Maryland, Department of Family and Community Medicine. We obtained institutional review board approval from the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

The GPTN-Maryland team has important partnerships with the Maryland Health Care Commission for policy, administrative supports, and alignment with the Maryland State Medical Society (MedChi). The team includes a quality improvement advisor and 6 part-time practice transformation coaches. All coaches are trained in practice transformation, extraction of quality metrics, reporting and improvement, and business efficiency, including return on investment.7 Each coach was assigned up to 20 practices to support in practice transformation, quality improvement, and preparation for value-based programs under the Quality Payment Program.8 All practices were offered monthly live continuing medical education programs about the Quality Payment Program and value-based programs in the state of Maryland, in addition to personalized coaching using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) TCPI Change Package.6

CMS provides each TCPI practice their Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR) data, which are used to determine adjustments to Medicare fee-for-service payments under the Quality Payment Program for the following year.9 Engaging practices in discussions of their QRUR data presented a challenge to coaches. The GPTN-Maryland team therefore identified a critical need for a simple practice transformation analytics tool to engage practices in these discussions.

METHODS

Recruitment for GPTN-Maryland began in 2016 and was led by MedChi. A total of 375 physicians and other clinicians were recruited in 2016, a total of 453 in 2017, and a total of 3 in 2018. (For maps of primary and specialty care practices, see Supplemental Figure 1, available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S73/suppl/DC1/.)

Practice Pathway in GPTN-Maryland

Practices are recruited to enroll into the GPTN-Maryland program to move through the 5 phases of transformation, including a 6-part patient and family engagement initiative.6 The coach uses the data from the baseline assessment to develop a work plan with the practice leaders and to implement new workflows using the TCPI Change Package, and ultimately assists practices in graduating to an advanced payment model.

Practice Analytics Dashboard as a Transformation Tool

We extracted cost, utilization, readmissions, disease burden, and payment adjustment data from the QRUR to develop the practice transformation analytics dashboard.7 The dashboard also includes data collected by the practices about brand of electronic health record used, whether it is linked to the local health information exchange, patient and family engagement data, phase of practice transformation, and quality metrics data. These data will be refreshed annually from the Merit-based Incentive Payment System report card, and quality metrics will be refreshed twice per year. We used a colorful simple design when developing the display dashboard (Supplemental Figure 2, available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S73/suppl/DC1/).

Coaching Using the Analytics Dashboard

The first step was to visit the practice to discuss the practice transformation analytics dashboard with leadership. Once opportunities for improving care delivery and quality of care were identified using the dashboard, the coaches used the TCPI Change Package and other resources to determine appropriate strategies for improvement. In instances where the Change Package did not address a gap—for example, how to reduce high health care costs identified in the QRUR—the GPTN-Maryland leadership and quality improvement advisor used evidence-based interventions identified through literature reviews and their own experience of best practices in practice transformation. Coaches will share the refreshed quality metrics every 6 months and the Merit-based Incentive Payment System data annually hereafter.

RESULTS

Practice Enrollment

A total of 48 practices with 109 practice sites are participating in GPTN-Maryland: 21 primary care practices with a total of 30 sites, 23 specialty practices with 54 sites, and 4 federally qualified health centers (specialty practices) with 25 practice locations (Supplemental Figure 1, available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S73/suppl/DC1/). These participating practices have a total of 12,100 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries reflected in the CMS QRUR data.

Practice Transformation

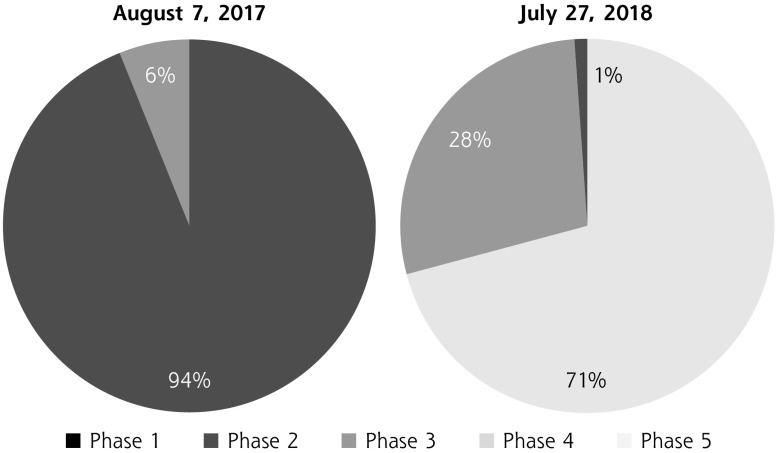

Figure 1 shows overall forward movement of practices through the phases of transformation using the practice transformation analytics dashboard over a 1-year period. There were large increases in the proportions of practices in phase 3 (from 6% to 28%) and phase 4 (from 0% to 71%), along with a concomitant decrease in the proportion in phase 2 (from 94% to 1%).

Figure 1.

Practice progression through transformation phases.

Notes: Phase 1: Setting practice goals for transformation. Phase 2: Using data to drive care delivery. Phase 3: Achieving progress on goals. Phase 4: Achieving benchmark status. Phase 5: Readiness to thrive as a business via pay for value.

Practice and Coach Response

Coaches presented the dashboard to each practice during a monthly site visit. Fully 96% of surveyed practices reported having previously reviewed their cost data in the QRUR (Table 1), which many found to be cumbersome. Practices reported that seeing their QRUR cost data in the dashboard format made it easier to understand.

Table 1.

GPTN-Maryland Practices’ Response to the Practice Transformation Analytics Dashboard

| Practice Type | Previously Reviewed QRUR Data | Had Favorable Response to Dashboard | Found Dashboard Data Actionable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes, No. (%) | No, No. (%) | Yes, No. (%) | No, No. (%) | Yes, No. (%) | No, No. (%) | |

| Primary care (n = 11) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (73) | 3 (27) | 6 (55) | 5 (45) |

| Specialty care (n = 14) | 13 (93) | 1 (7) | 10 (71) | 4 (29) | 6 (43) | 8 (57) |

GPTN-Maryland = Garden Practice Transformation Network in Maryland; QRUR = quality and resource use report.

On reviewing their dashboard overall, 72% of practices reported favorable responses to the data contained therein. Practices found the cost data to be of special interest, and 48% found the dashboard data to be actionable. Primary care practices were more likely than specialty care practices to find data actionable. One practice planned to develop an action plan to improve their key performance indicator data going forward. Another practice, however, reported that their electronic health record was not able to report accurate data, and they would not be able to show improvement from any actions they took.

As coaches used the dashboard in working with their practices, they reported finding it easier to relay the data at hand. The dashboard helped to structure the conversation with practices and identify areas where improvements could be made to reduce costs and improve key performance indicators. Additionally, coaches found the dashboard often promoted celebration as practices could see their QRUR cost savings, disease burden scores, and transformation progress in relation to those of their peers.

DISCUSSION

Practices in GPTN-Maryland have been coached in accessing and using data with varied degrees of uptake of these new practice workflows. Data review is one of the critical factors that leads to practice success in health system redesign and contributes to cost savings.4,10–12 Larger practices are more likely to have personnel dedicated to data generation and interpretation, whereas smaller practices are most likely to lack resources to review, interpret, and act on data that are mailed or placed on web servers for use.13 For effective engagement and action by practices, use of practice transformation tools to engage practices in quick reviews of actionable data is critical. Recent studies report that although transformation of practices creates additional work—including team building, data collection, reporting, and management—this work does not contribute to burnout.14–16

Data on patient and family engagement were included in the dashboard to highlight essential elements to success in developing therapeutic relationships with patients. Although patient and family advisory boards were not popular because of staffing challenges and time requirements, all practices were likely to include patient feedback in operations using patient portals, direct feedback, comment cards, and suggestion boxes.13

GPTN-Maryland practices will have the option in the future to participate in advanced payment programs, such as the Maryland Primary Care Program, that are part of the Total Cost of Care model.17 Practice engagement will be key to ensuring that ambulatory practices become partners in success in this model and participate in future payment models.18,19 The practice transformation analytics dashboard is one tool to support practice engagement in future advanced payment models.

In future research, observing changes in practice performance in GPTN-Maryland will further clarify the impact of the practice transformation analytics dashboard on the quality and cost of health care.

In conclusion, GPTN-Maryland is applying innovative approaches, including visual displays of practice transformation analytics data in dashboards, as tools to engage practices in transformation and in the delivery of patient-centered, value-based care. Future research is needed to ascertain how such practice tools affect patient care delivery, costs, quality, and experience.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melanie Cavaliere, MS, Program Manager for GPTN-Maryland, and the GPTN-Maryland Practice Transformation Coaches: Marsha Davenport, MD, MPH; Candice Morrison, MBA; Danielle Nugent; and Michelle Zancan, BSN, RN. We also thank David Sharp, PhD, for editorial suggestions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S73.

Funding support: This project was supported by subcontract number NJII 380G15 and funding opportunity number CMS-1L1-15-003 from the US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Disclaimer: The contents provided are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HHS or any of its agencies.

Previous presentations: Findings were previously presented at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; June 24-26, 2018; Seattle, Washington; and at the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting; November 9-13, 2018; Chicago, Illinois.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S73/suppl/DC1/).

References

- 1.Paustian ML, Alexander JA, El Reda DK, Wise CG, Green LA, Fetters MD. Partial and incremental PCMH practice transformation: implications for quality and costs. Health Serv Res. 2014; 49(1): 52–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal MB, Abrams MK, Bitton A, the Patient-Centered Medical Home Evaluators’ Collaborative Recommended core measures for evaluating the patient-centered medical home: cost, utilization, and clinical quality. The Commonwealth Fund; https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_data_brief_2012_1601_rosenthal_recommended_core_measures_pcmh_v2.pdf. Published May 2012 Accessed Apr 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012; 31(6): 1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David G, Saynisch PA, Smith-McLallen A. The economics of patient-centered care. J Health Econ. 2018; 59: 60–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro JL, Parchman ML, Meyers DS. Early evaluations of the medical home: building on a promising start. Am J Manag Care. 2012; 18(2): 105–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Transforming clinical practice initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/ Accessed Jul 13, 2018.

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Tools and resources for practice transformation and quality improvement. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/research-qi-practice/practice-transformation-qi.html Accessed Jul 13, 2018.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Quality payment program. https://qpp.cms.gov/ Accessed Jul 13, 2018.

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare FFS physician feedback program/value-based payment modifier. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/index.html Accessed Jul 13, 2018.

- 10.Aysola J, Schapira MM, Huo H, Werner RM. Organizational processes and patient experiences in the patient-centered medical home. Med Care. 2018; 56(6): 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stockdale SE, Rose D, Darling JE, et al. Communication among team members within the patient-centered medical home and patient satisfaction with providers: the mediating role of patient-provider communication. Med Care. 2018; 56(6): 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilello LA, Hall A, Harman J, et al. Key attributes of patient centered medical homes associated with patient activation of diabetes patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2018; 19(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul MM, Albert SL, Mijanovich T, Shih SC, Berry CA. Patient-centered care in small primary care practices in New York City: recognition versus reality. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017; 8(4): 228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman RE, Brown J, Stebbins P, et al. What matters in patient-centered medical home transformation: whole system evaluation outcomes of the Brown Primary Care Transformation Initiative. SAGE Open Med. 2018; 6: 2050312118781936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peikes D, Dale S, Ghosh A, et al. The Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: effects on spending, quality, patients, and physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018; 37(6): 890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu FM, Rubenstein LV, Yoon J. Team functioning as a predictor of patient outcomes in early medical home implementation. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018; 43(3): 238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Maryland Total Costs of Care model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/md-tccm/ Accessed Jul 10, 2018.

- 18.Burton RA, Lallemand NM, Peters RA, Zuckerman S, MAPCP Demonstration Evaluation Team Characteristics of patient-centered medical home initiatives that generated savings for Medicare: a qualitative multi-case analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018; 33(7): 1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns LR, Pauly MV. Transformation of the health care industry: curb your enthusiasm? Milbank Q. 2018; 96(1): 57–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]