Abstract

A 1-day-old child was brought to the clinic for evaluation of enlarged right eye (OD). On examination, OD showed buphthalmos with diffuse scleral melanocytosis, fleshy blackish-brown extrascleral mass with corneal extension, and secondary glaucoma. Anterior segment evaluation revealed darkly pigmented iris and fundus evaluation OD revealed a darkly pigmented choroidal lesion. The left eye was within normal limits. A clinical diagnosis of choroidal melanocytoma with ocular melanocytosis was made. Enucleation OD followed by orbital implant was performed. Histopathology showed features of diffuse ocular melanocytosis involving limbus, iris, ciliary body, choroid, sclera, optic nerve head, optic nerve sheath, along with choroidal melanocytoma with extrascleral tumour extension. We presume that choroidal melanocytoma may have arisen from ocular melanocytosis.

Keywords: paediatric oncology, glaucoma

Background

Ocular (oculodermal) melanocytosis is a congenital condition characterised by dermal pigmentation along the first and second divisions of the trigeminal nerve such as the ocular coats and periocular skin.1 It has been well established in literature that ocular melanocytosis predisposes to uveal malignant melanoma.2–11 Melanocytoma is a low-grade pigmented tumour arising from the melanocytes.1 Though considered a different entity from melanocytosis, they are believed to be the two extremes of the same congenital process of proliferation of pigmented cells. Histologically, melanocytosis shows spindle shaped cells whereas melanocytoma reveals polygonal cells. The occurrence of congenital uveal melanocytoma is extremely rare with only two published case reports. Herein, we describe a case of congenital choroidal melanocytoma with associated ocular melanocytosis.

Case presentation

A 1-day-old boy was evaluated for darkly pigmented and enlarged right eyeball since birth. He was delivered by an uncomplicated caesarean section. On examination, the right eye showed buphthalmos while the left appeared normal, and the dazzle reflex was positive in both eyes. Examination under anaesthesia revealed scleral melanocytosis along with a darkly pigmented extrascleral mass from 10 o’ clock to 8 o’ clock in the right eye with extension onto the cornea (figure 1A). Cornea was hazy in the pupillary axis. Left eye was normal. Intraocular pressures recorded using a Perkins tonometer were 28 mm Hg and 12 mm Hg in the right eye and left eye, respectively. Fundus examination showed a cup:disc ratio of 0.6:1 in the right eye with a darkly pigmented choroidal lesion. The left eye had a cup:disc ratio of 0.3:1 with healthy retina.

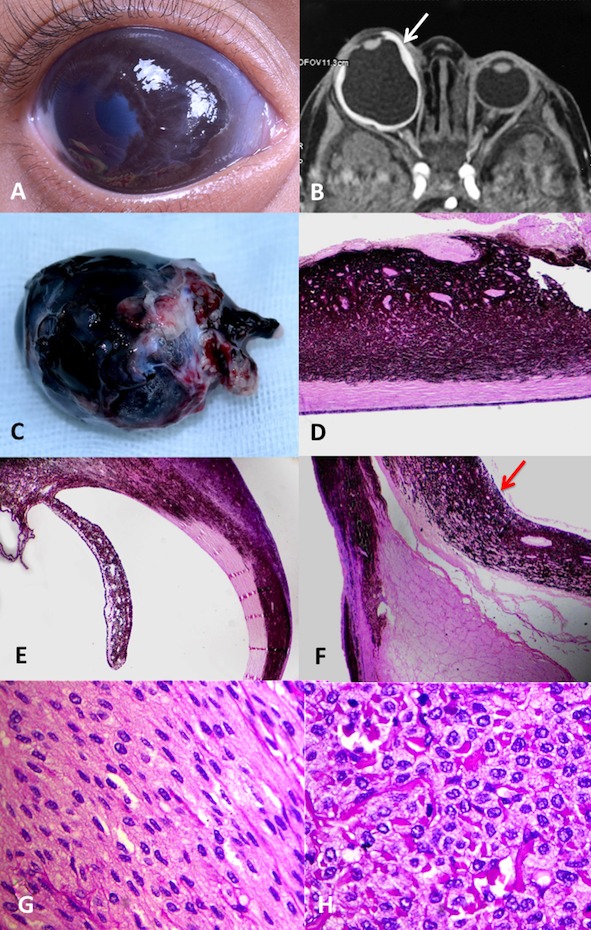

Figure 1.

Examination revealed (A) buphthalmic right globe with diffuse ocular pigmentation and fleshy episcleral mass nasally. (B) MRI orbit revealed enlarged and irregular right globe with thickened ocular coats (white arrow). (C) Enucleation of the right eye revealed diffuse pigmented episcleral mass with pigmentation of optic nerve sheath (black arrow). (D) Histopathology revealed choroidal melanocytoma with extrascleral tumour extension (H&E), 2 × magnification) and (E) diffuse ocular melanocytosis involving sclera and uvea with corneal and (F) optic nerve sheath extension of choroidal melanocytoma (red arrow) (H&E, 2 × magnification). (G) Photomicrograph showing the area of melanocytosis with proliferation of spindle cells (H&E, bleach section, 40 × magnification). (H) Photomicrograph showing the area of melanocytoma with proliferation of epithelioid cells without mitosis or necrosis (H&E, bleach section, 40 × magnification). A final diagnosis of right eye congenital choroidal melanocytoma with diffuse ocular melanocytosis was made.

Investigations

B-scan ultrasonography showed an enlarged right globe with an axial length of 32.55 mm with posterior staphyloma and choroidal thickening. Ultrasound biomicroscopy did not reveal any ciliary body mass. MRI revealed a disfigured and enlarged right globe with diffuse thickening of ocular coats (figure 1B).

Differential diagnosis

The choroidal lesion was presumed to be a choroidal melanocytoma due to its darkly pigmented nature and absence of exudative retinal detachment. However possibility of a congenital choroidal melanoma or a diffuse choroidal nevus could not be ruled out. A clinical diagnosis of right eye ocular melanocytosis with congenital choroidal melanocytoma and secondary glaucoma was made.

Treatment

The child was initially observed with topical antiglaucoma medications. Three months later, owing to uncontrolled glaucoma, right eye enucleation was performed and a 19 mm polymethyl methacrylate orbital implant was placed.

Outcome and follow-up

Gross examination (figure 1C) showed darkly pigmented sclera in its whole extent along with pigmentation of cornea, optic nerve sheath and proximal portion of all recti muscles except the lateral rectus. A fleshy blackish-brown mass was noted over the sclera and corneal surface. Histopathological examination (figure 1D–F) revealed heavily pigmented spindle shaped tumour cells in limbus, iris, ciliary body, choroid, sclera, optic nerve head, meningeal covering and focally in extrascleral soft tissue indicating widespread melanocytosis. Pigmented tumour cells replaced the choroid in its full thickness. There were two areas of prominent choroidal thickening. Bleached sections of these areas revealed plump polyhedral cells with abundant cytoplasm and small uniform nuclei. There was no evidence of atypia, necrosis or mitotic figures. Staining for Ki-67 showed a proliferation index of less than 1%. Based on histopathological findings, a final diagnosis of choroidal melanocytoma arising from congenital ocular melanocytosis was made. The child is doing well at 3 months follow-up.

Discussion

Ocular (oculodermal) melanocytosis is a congenital condition, most commonly unilateral and is characterised by hyperpigmentation of the uvea, sclera, episclera, optic disc, conjunctiva and optic nerve. It results from incomplete migration of melanocytes from the neural crest1 12 Observed first in the mid-nineteenth century by Ota13 and Tanino,14 it was histologically described by Reese in 1925.15 Gonder et al estimated the prevalence of this condition to be 0.38% in Caucasians and 0.14% in the African-American population.16 The lower prevalence in the black population could be owing to the difficulty in distinguishing the plump polyhedral nevus cells from normal heavily pigmented uveal melanocytes.

Melanocytomas are benign neoplasms arising from the melanocytes, which are embryologically derived from the neural crest cells.1 Due to the presence of abundant pigmented cells in the leptomeninges these tumours are commonly found in the posterior cranial fossa and cervical spine.17 Intraocular melanocytoma comprises of optic disc and uveal melanocytomas. The exact incidence of these intraocular lesions is unknown. This may be due to overlapping clinical features wherein a uveal melanocytoma has been diagnosed as choroidal nevus or a melanoma.18 Uveal melanocytoma is a deeply pigmented variant of uveal nevus known to occur in any part of the uveal tract. Rarely isolated orbital melanocytomas have been described.19 Patients with melanocytoma typically present in the third to the fifth decade. The occurrence of congenital uveal melanocytoma is extremely rare. Our literature search reveals only two cases of congenital uveal melanocytoma.20 21 Both cases describe neonates presenting with gradually progressive proptosis since birth due to melanocytoma involving the eye and the orbit.20 21 In our case, the melanocytoma was limited to the choroid in the setting of diffuse ocular melanocytosis.

Zimmerman described histological similarities between melanocytoma and ocular melanocytosis stating that melanocytoma was more a tumour-like accumulation of normal appearing uveal melanocytes.1 Shields et al also stated that melanocytoma and ocular melanocytosis, though considered as different entities, may be different expressions of the same congenital process.22 Gass et al also suggested that choroidal thickening in ocular melanocytosis comprises cells similar to those seen in melanocytoma.23 However, WHO classification of primary central nervous system melanocytic lesions includes focal and diffuse forms. Focal forms are meningeal melanocytoma and malignant melanoma while diffuse forms are diffuse melanocytosis and melanomatosis. Melanocytoma and melanocytosis are considered as different histological entities, where melanocytosis shows spindle cells with widespread parenchymal invasion and melanocytoma is a focal form which shows polygonal nevus cells.24 25 Synchronous occurrence of meningeal melanocytoma and oculodermal melanocytosis is rare, with only 12 cases reported in literature so far. Keng-Liang Kuo et al analysed these cases and concluded that these two entities when present synchronously, are located ipsilaterally and supratentorially. Inspite of the common origin from the neural crest, they are fundamentally different. When a patient with oculodermal melanocytosis presents with an intracranial lesion, primary melanocytic lesions should be considered first.26 In our patient, there was widespread melanocytosis since birth with only two focal areas of choroidal melanocytoma, thus we presume that melanocytoma in our case arose from the ocular melanocytosis.

Diffuse choroidal melanocytoma can mimic diffuse choroidal melanoma.27 28 In a setting of ocular melanocytosis, diffuse uveal melanoma is not uncommon. Diffuse choroidal melanomas are characterised by diffuse choroidal thickening with surface lipofuscin deposition and associated retinal detachment. In a study of 8101 patients with uveal melanoma, 1.5% were young patients aged 20 years or less, the youngest being 3 years of age.29 In this series, there were no cases of congenital choroidal melanoma. Extensive literature review revealed only seven reports of congenital ocular melanoma30–36 with a tendency to be diffuse in newborns. In our patient, there was no associated retinal detachment or surface lipofuscin deposition, and the lesion was blackish-brown in colour which led to a clinical diagnosis of choroidal melanocytoma.

Melanocytomas are typically stationary lesions and can be observed. However, 10%–15% can show mild growth and undergo spontaneous necrosis. In addition, presence of complete ocular melanocytosis is a well-documented risk factor for developing uveal malignant melanoma.11 Thus, close clinical follow-ups are extremely essential to document growth and detect transformation into melanoma. In our case, though the clinical diagnosis was choroidal melanocytoma, enucleation was performed after a brief period of observation in view of poor visual potential and uncontrolled secondary glaucoma.

Learning points.

Ocular melanocytosis is a risk factor for choroidal melanocytoma.

Buphthalmos and secondary glaucoma may be the presenting feature of congenital choroidal melanocytoma.

Routine fundus examination is mandatory in all cases of ocular melanocytosis to rule out uveal melanocytoma/melanoma.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM helped with planning, conduct and first draft. SJ helped with planning and reporting. SK helped with conception and design, and interpretation of data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Zimmerman LE. Melanocytes, melanocytic nevi, and MELANOCYTOMAS. Invest Ophthalmol 1965;4:11–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albert DM, Scheie HG. Naevus of Ota with malignant melanoma of the choroid. Report of a case. Arch Ophthalmol 1963;69:774–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yanoff M, Zimmerman LE. Histogenesis of malignant melanomas of the uvea. 3. The relationship of congenital ocular melanocytosis and neurofibromatosis in uveal melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol 1967;77:331–6. 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020333007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Makley TA, King CM. Malignant melanoma in melanosis oculi. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1967;71:638–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sabates FN, Yamashita T. Congenital melanosis oculi complicated by two independent malignant melanomas of the choroid. Arch Ophthalmol 1967;77:801–3. 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020803018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frezzotti R, Guerra R, Dragoni GP, et al. . Malignant melanoma of the choroid in a case of naevus of Ota. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1968;52:922–4. 10.1136/bjo.52.12.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohandessan M, Fetkenhour C, O'Grady R. Malignant melanoma of choroid in a case of nevus of Ota. Ann Ophthalmol 1979;11:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seelenfreund MH, Freilich DB. Ocular melanocytosis and malignant melanoma. NY State J. Med 1979;79:916–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamamoto T. Malignant melanoma of the choroid in the nevus of Ota. Ophthalmologica 1969;159:1–10. 10.1159/000305882 10.1159/000305882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Halasa A. Malignant melanoma in a case of bilateral nevus of Ota. Arch Ophthal 1970;84:176–8. 10.1001/archopht.1970.00990040178010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonder JR, Shields JA, Albert DM, et al. . Uveal malignant melanoma associated with ocular and oculodermal melanocytosis. Ophthalmology 1982;89:953–60. 10.1016/S0161-6420(82)34694-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC. Melanocytoma (hyperpigmented magnocellular nevus) of the uveal tract: the 34th G. Victor Simpson lecture. Retina 2007;27:730–9. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318030e81e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ota M. Nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris. Tokyo Med J 1939;63:1243–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ota M, Tanino H. Ube rein in Japan sehr Haufig vorkommende nafus form, navus fusco-caeruleus ophtalmomaxillaris and ihre beziehungen zu Der augenmelanomse. Jap J Derm Urol 1939;45:119–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reese AB. Melanosis oculi. A case with microscopic findings. Am J Ophthalmol 1925;8:865–70. 10.1016/S0002-9394(25)90920-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. . Ocular melanocytosis. A study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology 1982;89:950–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rahimi-Movaghar V, Karimi M. Meningeal melanocytoma of the brain and oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota): case report and literature review. Surg Neurol 2003;59:200–10. 10.1016/S0090-3019(02)01052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Esmaili DD, Mukai S, Jakobiec FA, et al. . Ocular melanocytoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2009;49:165–75. 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31819248d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tregnago AC, Furlan MV, Bezerra SM, et al. . Orbital melanocytoma completely resected with conservative surgery in association with ipsilateral nevus of Ota: report of a case and review of the literature. Head Neck 2015;37:E49–55. 10.1002/hed.23828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Char DH, Crawford JB, Ablin AR, et al. . Orbital melanocytic hamartoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;91:357–61. 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90290-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bajaj MS, Khuraijam N, Sen S. Congenital melanocytoma manifesting as proptosis with multiple cutaneous melanocytic nevi and oculodermal melanosis. Arch Ophthal 2009;127:936–9. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC, et al. . Malignant melanoma arising from a large uveal melanocytoma in a patient with oculodermal melanocytosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:990–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. M. Gass JD. Problems in the differential diagnosis of choroidal nevi and malignant melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol 1977;83:299–323. 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90726-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamasaki O, Nakahara T, Sakamoto S, et al. . Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma. Neurol Med Chir 2002;42:504–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gupta A, Ahmad FU, Sharma MC, et al. . Cerebellopontine angle meningeal melanocytoma: a rare tumor in an uncommon location. J Neurosurg 2007;106:1094–7. 10.3171/jns.2007.106.6.1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuo K-L, Lin C-L, Wu C-H, et al. . Meningeal melanocytoma associated with nevus of Ota: analysis of twelve reported cases. World Neurosurg 2019;127:e311–20. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shields JA, Eagle RC, Shields CL, et al. . Diffuse choroidal melanocytoma simulating melanoma in a child with ocular melanocytosis. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2010;4:164–7. 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181a91d56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haas BD, Jakobiec FA, Iwamoto T, et al. . Diffuse choroidal melanocytoma in a child. A lesion extending the spectrum of melanocytic hamartomas. Ophthalmology 1986;93:1632–8. 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33519-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shields CL, Kaliki S, Arepalli S, et al. . Uveal melanoma in children and teenagers. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology 2013;27:197–201. 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Broadway D, Taylor D, Lang S, et al. . Congenital malignant melanoma of the eye. Cancer 1991;67:2642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Posnick JC, Chen P, Zuker R, et al. . Extensive malignant melanoma of the uvea in childhood: resection and immediate reconstruction with microsurgical and craniofacial techniques. Ann Plast Surg 1993;31:265–70. 10.1097/00000637-199309000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greer CH. Congenital melanoma of the anterior uvea. Arch Ophthal 1966;76:77–8. 10.1001/archopht.1966.03850010079015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palazzi MA, Ober MD, Abreu HFH, et al. . Congenital uveal malignant melanoma: a case report. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 2005;40:611–5. 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pukrushpan P, Tulvatana W, Pittayapongpat R. Congenital uveal malignant melanoma. J Aapos 2014;18:199–201. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rai A, Al-Jaradi M, Burnier M, et al. . Congenital choroidal melanoma in an infant. Can J Ophthalmol 2011;46:203–4. 10.3129/i10-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singh AD, Schoenfield LA, Bastian BC, et al. . Biscotti cv congenital uveal melanoma? Surv Ophthalmol 2016;61:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]