Abstract

Objective

Non-specific musculoskeletal pain is common in subjects destined to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA). We evaluated psoriatic patients with arthralgia (PsOAr) compared with psoriasis alone (PsO) and healthy controls (HCs) using ultrasonography (US) to investigate the anatomical basis for joint symptoms in PsOAr and the link between these imaging findings and subsequent PsA transition.

Methods

A cross-sectional prevalence analysis of clinical and US abnormalities (including inflammatory and structural lesions) in PsOAr (n=61), PsO (n=57) and HCs (n=57) was performed, with subsequent prospective follow-up for PsA development.

Results

Tenosynovitis was the only significant sonographic feature that differed between PsOAr and PsO (29.5% vs 5.3%, p<0.001), although synovitis and enthesitis were numerically more frequent in PsOAr. Five patients in PsOAr and one in PsO group developed PsA, with an incidence rate of 109.2/1000 person-years in PsOAr vs 13.4/1000 person-years in PsO (p=0.03). Visual Analogue Scale pain, Health Assessment Questionnaire, joint tenderness and US active enthesitis were baseline variables associated with PsA development.

Conclusion

Tenosynovitis was associated with arthralgia in subjects with psoriasis. Baseline US evidence of enthesitis was associated with clinical PsA development in the longitudinal analysis. These findings are relevant for enriching for subjects at risk of imminent PsA development.

Keywords: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriatic arthralgia, pain, ultrasound, preclinical phase

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Patients with psoriasis have a period of non-specific joint symptoms (ie, arthralgia) before psoriatic arthritis (PsA) development, but the anatomical basis for such arthralgia remains to be defined.

What does this study add?

Tenosynovitis could be an important contributor to non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms in psoriatic patients with arthralgia (PsOAr).

Clinically, PsOAr patients were more prone to develop PsA with longitudinal evaluation and the baseline sonographic detection of enthesitis was associated with clinical PsA development.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

PsOAr patients could be a subgroup of psoriatic patients in which a strict rheumatological monitoring or disease interception with psoriasis directed therapy could be envisaged.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common and potentially debilitating arthropathy that can occur in up to a third of patients with psoriasis.1 It is well established that joint damage can occur early in the course of PsA, so early disease recognition is imperative. Given that psoriasis predates PsA by a decade or more, then skin involvement offers the opportunity to investigate risk factors and predictors of PsA development.2 The incidence of PsA in different psoriasis cohorts is between 0.3% and 3.5% per annum.2 3 In rheumatoid arthritis, anti citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)+ cases have a preclinical phase of disease characterised by clinically suspected arthralgia4 and imaging studies have shown that this phase of disease is associated with synovitis and tenosynovitis.5 6

In PsA, it was clinically recognised that the complex of symptoms, experienced by patients in their preclinical phases of disease, is heterogeneous, from fatigue and depressive symptoms to arthralgia. However, prospective studies focussing on symptoms suspicious for PsA development are still lacking. Recently, Eder et al showed in a longitudinal cohort of psoriasis that cases destined to developed PsA had antedating non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms, without distinct findings suggestive for PsA on physical examination.7 The anatomical basis for joint pain in the preclinical phase of PsA is not yet understood, and musculoskeletal ultrasonography (US) could be a reliable modality to detect musculoskeletal inflammatory lesions in these patients with psoriasis.8–11 Moreover, this sonographic-determined inflammation appears to regress under systemic therapy for skin disease raising the possibility that skin-directed therapy may prevent arthritis development.12 However, the current inability to accurately enrich for imminent PsA means that the question of PsA prevention strategies remains in its infancy.13

In this study we explored, by means of US, the anatomical basis for arthralgia in subjects with psoriasis. We followed up this patient group looking at the rate of PsA development in patients with psoriasis with and without arthralgia and linked this to baseline imaging findings. Our findings confirmed that arthralgia in subjects with psoriasis is associated with PsA development with our imaging data showing important roles for baseline imaging-determined tenosynovitis or enthesitis on both symptoms and disease evolution.

Methods

Study population

Patients with psoriasis and age-matched randomly selected healthy controls (HCs) were recruited from rheumatology and dermatology clinics from seven centres in Italy. The HCs were non-blood relatives of enrolled patients or dermatological patients with other skin disease. Before enrolment all subjects were evaluated by rheumatologists in order to exclude inflammatory arthritis and/or spondylitis, either current or in the past (ie, current or negative history of arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis or inflammatory back pain) (box 1). Patients with psoriasis were divided in psoriasis cases with arthralgia (PsOAr) and without arthralgia (PsO). The PsOAr was defined as recent onset (≤12 months) of non-inflammatory joint and/or entheseal pain, without current or past inflammatory signs/symptoms, and with Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria for a diagnosis of PsA not being fulfilled (box 1).14 Concomitant osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia were also excluded. Previous or current use of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or small molecules, and the use, within 3 months from enrolment, of conventional synthetic DMARDs, steroid therapy (oral and intra-articular), retinoids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (chronically) were stated as exclusion criteria. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in box 1. All patients gave oral and written informed consent for all procedures, which were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Age ≥18 years

Current cutaneous psoriasis and/or nail psoriasis diagnosed by a dermatologist

Negative history of arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis or inflammatory back pain

Absence of clinical signs of osteoarthritis* and/or fibromyalgia†

Absence of signs of active arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis or inflammatory back pain atenrolment, evaluated by rheumatologist

Exclusion criteria

Satisfaction of CASPAR criteria

Use of conventional synthetic DMARDs, steroid therapy (oral and intra-articular), retinoids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (chronically)within 3 months from enrolement

Previous or actual use of bDMARDs or small molecules (eg, Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor [PDE4i])

*The clinical diagnosis of osteoarthritis was ruled out by a rheumatologist.†Fibromyalgia was tested by ACR criteria (Wolfe et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 May;62(5):600–10)

Study design

The study consisted of two phases: (a) cross-sectional prevalence analysis of clinical and US abnormalities in PsOAr compared with PsO and HCs; (b) prospective analysis looking for the development of PsA. The diagnosis of PsA was clinical and made by rheumatologists, blinded to previous US results, if CASPAR criteria were fulfilled. In the prospective follow-up, all psoriasis participants were reassessed every 6 months or according to clinical practice. Patients were instructed to contact the rheumatologist prior to their scheduled assessment if they developed inflammatory symptoms (eg, worsening of joint pain, morning stiffness). In the prospective phase, only patients with psoriasis with a follow-up of at least 3 months were included for final analysis. In order to increase the validity and reliability of the results, the participants satisfied prerequisites: (1) expertise in early PsA and in combined dermatological-rheumatological assessment; (2) availability of a high-level US machine including high-level US probes (>14 MHz); (3) reliability exercise on US static images with a kappa statistics value >0.7 compared with ‘gold-standard’ scorers (AZ, AI) (table 1).

Table 1.

Ultrasonographic definitions of inflammatory and damage lesions and agreement between sonographers expressed by Kappa value

| Ultrasonographic lesion | Definition |

| Grey scale (GS) synovitis | GS synovitis was evaluated by including its two components (ie, joint effusion and synovial membrane hypertrophy), which was assessed according to the OMERACT definitions.26 In GS, the two components of synovitis (ie, joint effusion and synovial hypertrophy) was scored together according to a 4-point semi-quantitative assessment as follows: synovitis: grade 0=no synovitis; grade 1=minimal synovitis (below or at the level of bony joint line); grade 2=moderate synovitis (above level of bony joint line but without full distension of joint capsule); grade 3=severe synovitis (above level of bony joint line with distension of joint capsule which will appear convex).27 28 |

| Power Doppler (PD) synovitis | PD synovitis was scored by using a semi-quantitative 4-point scale, as follows: grade 0=no flow within the synovium; grade 1=up to three single spots signals or up to two confluent spots signals or one confluent spot+up to two single spots signals; grade 2=PD signals covering <50% of the area of the synovium; grade 3=PD signals in >50% of the area of the synovium.29 |

| Joint erosion | Erosions were defined as intra-articular discontinuity of the bone surface that is visible in two perpendicular planes.26 |

| Joint osteoproliferation | The OMERACT definition of osteophyte (osteoproliferation at the joint margins) was used.30 |

| GS tenosynovitis | GS tenosynovitis was defined on GS as abnormal anechoic and/or hypoechoic (relative to tendon fibres) tendon sheath widening, which can be related to both the presence of tenosynovial abnormal fluid and/or hypertrophy. On GS, tenosynovitis was graded according to a 4-point semi-quantitative scoring system as follows: grade 0=normal; grade 1=minimal; grade 2=moderate; grade 3=severe. Both longitudinal and transverse planes were performed in order to confirm the findings.31 |

| PD tenosynovitis | PD tenosynovitis was defined as the presence of peritendinous Doppler signal within the synovial sheath, seen in two perpendicular planes, excluding normal feeding vessels (ie, vessels at the mesotenon or vinculae or vessels entering the synovial sheath from surrounding tissues) only if the tendon shows peritendinous synovial sheath widening on B-mode. A 4-point semi-quantitative scoring system (ie, grade 0=no Doppler signal; grade 1=minimal; grade 2=moderate; grade 3=severe) can be used to score pathological peritendinous Doppler signal within the synovial sheath.31 |

| Enthesitis | Enthesitis was defined in accordance with the recently published OMERACT definitions and the registered elementary lesions will be: hypoechogenicity of the enthesis (hypoechoic tendon with loss of the normal fibrillar pattern); increased thickness of tendon at its insertion*; enthesophyte (a step up bony prominence at the end of the normal bone contour); calcifications; bone erosion at the enthesis; PD activity at enthesis <2 mm from the bone insertion.17 |

| Bursitis | Bursitis will be defined as an abnormal distension of the bursal wall, due to local effusion and/or synovial proliferation. PD signal was evaluated as present/absent.32 |

| Peritendinits of the extensor tendon on metacarpophalangeal joint | The presence of peritenon extensor tendon inflammation was investigated by dorsal scans at the level of all fingers of both hands. This abnormality was defined as a hypoechoic swelling of the soft tissues surrounding the extensor digitorum tendons, with or without peritendinous PD signal.33 34 |

OMERACT, Outcome Measures in Rheumatology.

| Sonographer | Observed agreement | Expected change agreement | Kappa value |

| 1 | 0.88 | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| 2 | 0.90 | 0.37 | 0.85 |

| 3 | 0.97 | 0.37 | 0.95 |

| 4 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.72 |

| 5 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.92 |

Kappa value=(observed agreement–expected change agreement)/(1–expected change agreement).

*Entheseal thickening measured at 2 mm proximal to the bony contour (abnormality definitions: quadriceps tendon >6.1 mm, proximal and distal patellar ligament >4 mm, Achilles tendon >5.29 mm, plantar aponeurosis >4.4 mm).32

Clinical assessment

For each patient, we recorded demographic data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol intake and comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, uveitis, depression, neoplastic disease, cardiovascular disease). Articular and entheseal examination, including tender joints count (68 joints) and tender entheses count at six entheses, as defined by Leeds Enthesitis Index, plus quadriceps patellar insertion, proximal and distal patellar insertion and plantar fascia was performed by a rheumatologist. Articular regions that had suffered from prior bone fractures or had undergone surgical procedures were excluded from the clinical examination. Each patient completed a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for musculoskeletal pain and a Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) to document physical function. Psoriasis subtype, nail involvement, age at disease onset and previous medications for cutaneous or nail psoriasis were recorded. Severity of psoriasis and nail involvement were scored according to the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), respectively.

Ultrasonographic assessment

All sonographers were rheumatologists with experience (≥5 years) in US examinations of PsA and blinded to diagnosis and clinical findings. To standardise and reach an agreement on the US definitions a meeting was organised before the starting of the study. In addition, all sonographers had a booklet with standard US imaging instructions. Reliability exercise on static images was performed before the start of the study (table 1). US analysis was performed in the same day of clinical examination and focused in a longitudinal and transverse scan of 42 regions encompassing the following: metacarpophalangeal, proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the hands, wrists, knees, metatarsophalangeal joints, 12 entheses (Achilles, quadriceps, proximal and distal patellar, plantar aponeurosis and common extensor tendon entheses), the 2 retro-calcaneal bursae and 32 tendons (extensor digitorum tendons of the hands, flexor digitorum tendons of the hands and extensor tendon compartments of the wrist). As for clinical examination, articular regions that had suffered from prior bone fractures or had undergone surgical procedures were excluded from the US examination. The sites to be scanned and US definitions of inflammatory lesions (ie, synovitis, tenosynovitis, enthesitis, peritenon extensor tendon inflammation and bursitis) and damage lesions (ie, joint erosions, entheseal erosions, enthesophytes and articular osteoproliferation) were defined according to a previous protocol9 15 16 and are presented in table 1. Active synovitis was defined if both articular grey scale (GS) synovitis (GS ≥2) and intra-articular power Doppler (PD) signal (PD ≥1) were detected. Active enthesitis was defined by the lack of the homogeneous fibrillar pattern in the enthesis (<2 mm from the cortical bone) with loss of the tightly packed echogenic lines after correcting for anisotropy with concomitant PD signal at bone insertion (<2 mm from the cortical bone).9 17

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were presented as the mean and SD, median and IQR. Categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between independent means were analysed using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test while, to test the difference between groups, accurate Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables were used. In the longitudinal analysis, the incidence rates were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. This is the first study to assess the anatomic basis for arthralgia and their linkage with PsA development in subjects with psoriasis by means of US. Considering the sample size, possible number of events and the wide range of clinical and US predictors this analysis was considered exploratory. A predictive model for PsA development was not feasible, therefore the association between groups based on the presence of event (ie, PsA development) was made. Data management and analysis were performed using REDCap and R software.

Results

Cross-sectional study

Sixty-one PsOAr, 57 PsO and 57 HCs were included from 7 Italian centres for the cross-sectional analysis. All underwent full clinical and US examinations: a total number of 7350 joints and 2100 entheses were scanned.

Patient characteristics

The mean (±SD) age in years was 50.49 (±12.27) in PsOAr, 50.65 (±16.62) in PsO and 47.91 (±13.03) in HCs, without significant differences between groups (table 2). PsO group comprised a lower percentage of female (49.1%) compared with HCs (69.6%) (p=0.03), and with PsOAr (55.7%) (p=0.58). As expected, the body mass index (BMI) was significantly higher in PsOAr (26±4.8) and PsO (25±3.95), while in HCs was 23±3.67 (p=0.001 and 0.002, respectively). Depression and hypertension were more frequent in PsOAr cohort than in HCs, but without differences between psoriasis cohorts. Considering the musculoskeletal complaint, PsOAr, compared with PsO, had a higher VAS pain (4±2.35 vs 2±2.39, p<0.001), tender joints count (2.98±4.7 vs 0.49±0.98, p<0.001) and tender enthesis count (0.64±1.14 vs 0.09±0.34, p<0.001) (table 2). All these variables were also significantly higher in PsOAr compared with HCs. No significant differences emerged between PsO and HCs for VAS pain (2±2.39 vs 2±2, p=0.97), tender joints count (0.49±0.98 vs 0.37±1.1, p=0.13) and tender enthesis count (0.09±0.34 vs 0.02±0.13, p=0.17) (table 2). PASI and NAPSI scores were similar between PsOAr and PsO.

Table 2.

Baseline features of the study cohorts

| HCs (n=57) | PsO (n=57) | PsOAr (n=61) | P value PsOAr vs PsO vs HCs |

P value PsO vs HCs |

P value PsOAr vs HCs |

P value PsOAr vs PsO |

|

| Baseline data | |||||||

| Age, mean (±SD) | 47.91 (±13.03) | 50.65 (±16.62) | 50.49 (±12.27) | 0.44 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (69.64%) | 28 (49.12%) | 34 (55.74%) | 0.08 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Smoking, n (%) | 8 (14.55%) | 17 (29.82%) | 5 (8.2%) | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.008 |

| BMI, mean (±SD) | 23 (±3.67) | 25 (±3.95) | 26 (±4.8) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.96 |

| Family history of PsA, n (%) | 1 (1.75%) | 9 (16.07%) | 7 (11.48%) | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.062 | 0.59 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (3.51%) | 3 (5.26%) | 5 (8.2%) | 0.61 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 6 (10.53%) | 11 (19.3%) | 19 (31.15%) | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.007 | 0.20 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 4 (7.02%) | 4 (7.02%) | 11 (18.03%) | 0.10 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Depression, n (%) | 1 (1.75%) | 3 (5.26%) | 9 (14.75%) | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.017 | 0.13 |

| Patient-reported symptoms and baseline clinical examination | |||||||

| VAS pain (0–10), mean (±SD) | 2 (±2) | 2 (±2.39) | 4 (±2.35) | <0.001 | 0.97 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HAQ, mean (±SD) | 0 (±0.21) | 0 (±0.48) | 0 (±0.39) | <0.001 | 0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tender joints count, mean (±SD) | 0.37 (±1.1) | 0.49 (±0.98) | 2.98 (±4.7) | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tender enthesis count, mean (±SD) | 0.02 (±0.13) | 0.09 (±0.34) | 0.64 (±1.14) | <0.001 | 0.17 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PASI, mean (±SD) | n.a. | 3.79 (±3.29) | 4.34 (±5.65) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.92 |

| NAPSI, mean (±SD) | n.a. | 9.07 (±8.50) | 8.48 (±7.95) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.76 |

Joints tenderness was evaluated in 68 joints. Tender entheses count was evaluated in six sites of LEI plus bilateral quadriceps patellar insertion, proximal and distal patellar insertion and plantar fascia.

Values in bold signifies p value ≤0.05.

BMI, body mass index; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HC, healthy control; LEI, Leeds enthesitis index; n.a., not applicable; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis alone; PsOAr, psoriatic patients with arthralgia; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

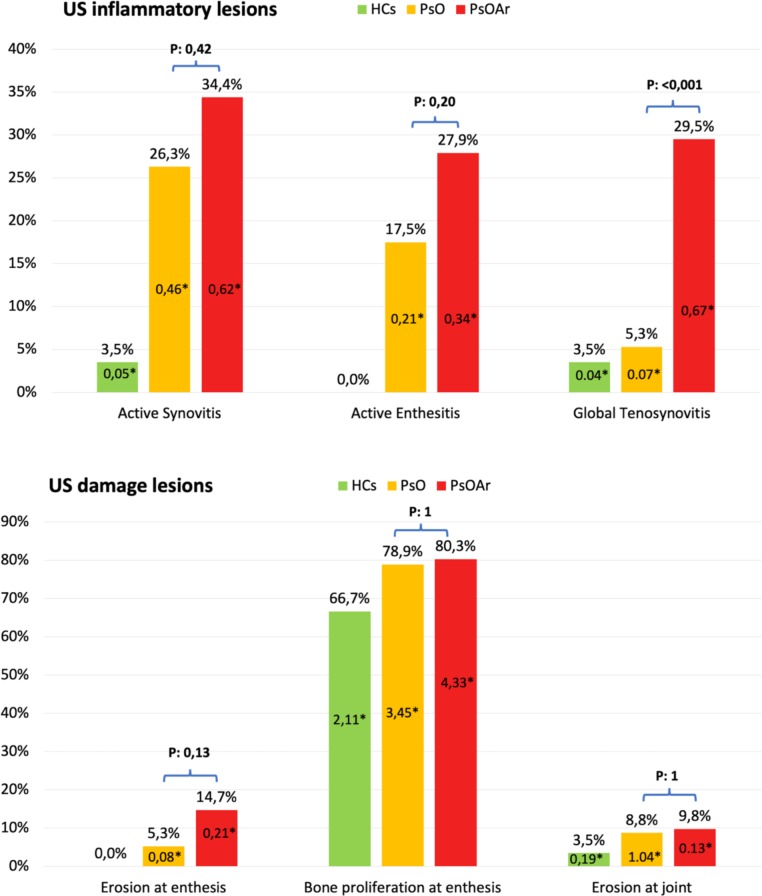

Ultrasonographic inflammatory features

In the PsOAr cohort, 18 out of the 61 (29.5%) patients showed tenosynovitis in at least one region as evaluated by GS (grade 1 in 17/18 patients and grade 2 in 1/18), compared with 3 out of the 57 PsO patients (5.3%) (p<0.001) and 2/57 (3.5%) in HCs, all grade 1 for PsO and HCs (figure 1). Conversely, no significant difference was found between cohorts when tenosynovitis was analysed for PD. The presence of at least one active region of synovitis and active enthesitis, although more frequent in PsOAr compared with PsO (34.4% vs 26.3% and 27.9% vs 17.5%, respectively) did not significantly differ (p=0.42 and 0.2, respectively). In addition, no other significant differences between PsOAr and PsO were found as regard bursitis or peritendinitis. Active synovitis and active enthesitis significantly differed between both PsOAr versus HCs and PsO versus HCs (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of ultrasonographic lesion in HCs, PsO and PsOAr expressed as percentage of patients with at least one feature and as the mean number (*) of US lesion per patient. HC, healthy control; PsO, psoriasis alone; PsOAr, psoriatic patients with arthralgia; US, ultrasonography.

Ultrasonographic structural/damage features

In PsOAr, 9 out of the 61 patients (14.7%) showed at least one entheseal erosion compared with 3 out of the 57 PsO patients (5.3%) (p=0.13) and none of the HCs (p=0.003) (figure 1).

The mean number of enthesophyte per patient was significantly different comparing cases with HCs (4.33±2.84 in PsOAr and 3.45±2.7 in PsO vs 2.11±2.17 in HCs, p<0.01), but was not substantially different between PsOAr and PsO (figure 1). No significant differences between the three cohorts were found for articular erosions and osteoproliferation (figure 1).

Correlation between the sonographically detected inflammation and the baseline clinical variables

In the PsOAr cohort, both patients with US determined active synovitis and active enthesitis had higher NAPSI value (13.7±7.74 vs 5.07±6.18, p=0.01 and 13.4±8.4 vs 5.3±5.9, p=0.03, respectively) (table 3). This was not observed in the PsO cohort, where only the age (ie, older) was associated with active synovitis (58.9 years±11.4 vs 47.7 years±17.3, p=0.02) (table 3) and entheseal hypoechogencity and/or thickening (55.8 years±17.9 vs 48.4 years±15.8, p=0.04). Evaluating together PsOAr and PsO (n=118), US determined active enthesitis was found more frequently in non-smoker patients (21.9% vs 7.4%, p=0.009) but also in enthesopathy (ie, entheseal hypoechogencity and/or thickening) regardless entheseal PD signal (25.9% vs 4.8%, p=0.002). A similar result was close to statistical significance also for active synovitis (p=0.07); furthermore, the presence of US active enthesitis was associated with higher VAS pain (3.7±2.4 vs 2.6±2.5, p=0.03).

Table 3.

Association between sonographic detected active synovitis and enthesitis with baseline clinical data

| Event | Nonevent | P value | Event | Non-event | P value | |

| Active synovitis in PsO (n=57) | Active synovitis in PsOAr (n=61) | |||||

| Age, mean (±SD) | 58.93 (±11.14) | 47.69 (±17.35) | 0.019 | 51.05 (±10.03) | 50.2 (±13.41) | 0.74 |

| Female, n (%) | 5 (33.33%) | 23 (54.76%) | 0.23 | 10 (47.62%) | 24 (60%) | 0.42 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 3 (20%) | 14 (33.3%) | 0.483 | 0 | 5 (12.5%) | 0.18 |

| BMI, mean (±SD) | 26.52 (±3.32) | 25.05 (±4.12) | 0.195 | 26.73 (±4.5) | 25.48 (±4.96) | 0.23 |

| Alcohol, n (%) (daily intake) | 0 | 0 | 0.817 | 0 | 0 | 0.47 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (6.67%) | 2 (4.76%) | 1 | 2 (9.52%) | 3 (7.5%) | 1 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2 (13.33%) | 9 (21.43%) | 0.709 | 6 (28.57%) | 13 (32.5%) | 1 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.52%) | 0.564 | 4 (19.05%) | 7 (17.5%) | 1 |

| HAQ, mean (±SD) | 0.17 (±0.28) | 0.21 (±0.53) | 0.886 | 0.23 (±0.22) | 0.43 (±0.45) | 0.14 |

| VAS, mean (±SD) | 1.57 (±1.99) | 1.96 (±2.53) | 0.885 | 4.02 (±2.72) | 3.65 (±2.15) | 0.84 |

| PASI, mean (±SD) | 4.57 (±4.15) | 3.53 (±2.94) | 0.489 | 4.42 (±2.76) | 4.30 (±6.80) | 0.09 |

| NAPSI, mean (±SD) | 9.17 (±5.62) | 9.03 (±9.43) | 0.390 | 13.7 (±7.74) | 5.07 (±6.18) | 0.014 |

Values in bold signifies p value ≤0.05.

| Active enthesitis in PsO (n=57) | Active enthesitis in PsOAr (n=61) | |||||

| Age, mean (±SD) | 57.2 (±11.78) | 49.26 (±17.26) | 0.2 | 54.18 (±6.93) | 49.07 (±13.6) | 0.16 |

| Female, n (%) | 2 (20%) | 26 (55.32%) | 0.079 | 10 (58.82%) | 24 (54.55%) | 1 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 1 (10%) | 16 (34.04%) | 0.153 | 1 (5.88%) | 4 (9.09%) | 0.06 |

| BMI, mean (±SD) | 26.39 (±3.34) | 25.23 (±4.07) | 0.309 | 29.95 (±3.73) | 25.9 (±5.2) | 0.58 |

| Alcohol, n (%) (daily intake) | 0 | 0 | 0.955 | 0 | 0 | 0.87 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 | 3 (6.38%) | 1 | 2 (11.76%) | 3 (6.82%) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2 (20%) | 9 (19.15%) | 1 | 4 (23.53%) | 15 (34.09%) | 0.54 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 0 | 4 (8.51%) | 1 | 4 (23.53%) | 7 (15.91%) | 0.48 |

| HAQ, mean (±SD) | 0.35 (±0.94) | 0.17 (±0.32) | 0.684 | 0.34 (±0.3) | 0.37 (±0.42) | 0.87 |

| VAS, mean (±SD) | 2.56 (±2.52) | 1.73 (±2.37) | 0.254 | 4.35 (±2.17) | 3.56 (±2.4) | 0.18 |

| PASI, mean (±SD) | 4.52 (±2.58) | 3.65 (±3.41) | 0.153 | 3.86 (±2.69) | 4.53 (±6.46) | 0.59 |

| NAPSI, mean (±SD) | 8 (±7.05) | 9.31 (±8.86) | 0.903 | 13.44 (±8.43) | 5.29 (±5.94) | 0.03 |

BMI, body mass index; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsO, psoriasis alone; PsOAr, psoriatic patients with arthralgia; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Longitudinal study

One hundred and two patients (54 in PsOAr and 48 in PsO cohort), with full clinical data and with a follow-up of at least 3 months, were included. The mean time of follow-up was 309.6±113.6 days (median 312, IQR 233–354 days) in PsOAr and 566.2±187.6 days (median 617.5, IQR 601–674 days) in PsO. Five patients in PsOAr cohort and one patient in PsO developed PsA, with an incidence rate of 109.2/1000 person-years in PsOAr and 13.4/1000 person-years in PsO (p=0.03). Patients which developed PsA had significantly higher VAS pain at baseline (5.92±2.01 vs 2.63±2.35, p=0.004), HAQ (0.44±0.22 vs 0.26±0.38, p=0.03), joints tenderness (6.8±10.87 vs 1.74±3.16, p=0.03). Sonographically determined active enthesitis (0.67±0.52 vs 0.27±0.55, p=0.03) was also associated with disease evolution (table 4). However, tenosynovitis which was most strongly linked to non-specific symptoms at baseline was not linked to PsA development in these cohorts (table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the baseline clinical and US variables between patients (with a follow-up of at least 3 months) without development of PsA and those developed PsA

| PsO+PsOAr without PsA development (n=96) | PsO+PsOAr with PsA development (n=6) | P value | |

| Age, mean (±SD) | 50.23 (±15.25) | 59.17 (±8.75) | 0.15 |

| Female, n (%) | 54 (56.25 %) | 3 (50 %) | 1 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 18 (18.75 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.62 |

| BMI, mean (±SD) | 25 (±4.29) | 28 (±3.16) | 0.08 |

| Family history of PsA, n (%) | 14 (14.74 %) | 1 (16.67 %) | 1 |

| VAS pain (0–10), mean (±SD) | 2.63 (±2.35) | 5.92 (±2.01) | <0.01 |

| HAQ, mean (±SD) | 0.26 (±0.38) | 0.44 (±0.22) | 0.03 |

| Tender joints count, mean (±SD) | 1.74 (±3.16) | 6.8 (±10.87) | 0.03 |

| Tender enthesis count, mean (±SD) | 0.29 (±0.60) | 1 (±2.45) | 0.96 |

| Active synovitis, n* (%) | 20 (20.83 %) | 2 (33.33 %) | 0.61 |

| Active synovitis, mean joint number (±SD) | 0.3 (±0.68) | 1 (±1.67) | 0.31 |

| Active enthesitis, n† (%) | 21 (21.88 %) | 4 (66.67 %) | 0.03 |

| Active enthesitis, mean entheseal number (±SD) | 0.27 (±0.55) | 0.67 (±0.52) | 0.03 |

| GS tenosynovitis, n‡ (%) | 19 (19.8%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 |

| GS tenosynovitis, mean (±SD) | 0.41 (1.07) | 0.25 (1.22) | 0.97 |

Values in bld signifies p value ≤0.05.

*Number of patients with at least one active synovitis.

†Active enthesitis.

‡Tenosynovitis in GS.

BMI, body mass index; GS, grey scale; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HC, healthy control; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis alone; PsOAr, psoriasis patients with arthralgia; US, ultrasonography; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Discussion

This is the first study to perform a combined clinical and US analysis on the transition phase of PsA, here defined as PsOAr. Through the prospective assessment, the PsOAr cohort showed a significantly higher incidence rate of PsA compared with PsO, consistent with the previous clinical observations that non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms were a risk factor for PsA development.7 18 We found that sonographically determined synovitis, enthesitis and tenosynovitis were numerically more frequent in the PsOAr group compared with PsO. However, only tenosynovitis, evaluated in GS, showed a strong significant association with baseline PsOAr. This evidence suggests that tenosynovitis could be an important contributor to non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms in patients with psoriasis, while synovitis and enthesitis may also occur without symptoms. Although the numbers were small, our study suggests that sonographically determined enthesitis was linked to the future evolution of PsA, while tenosynovitis was not. This detection supports the cardinal role of enthesitis observed in experimental models of PsA and in also some imaging studies.13 19 Moreover, previous observations showed that accessory pulley as mini-entheses may provide a mechanistic link between enthesitis and tenosynovitis but further work is needed.20 21 In this study, it is interesting to note that psoriatic nail involvement correlated with subclinical inflammation, but only in the arthralgia cohort. Higher NAPSI values were indeed found in PsOAr patients with sonographically determined active synovitis and active enthesitis, confirming the nail involvement as a marker of musculoskeletal inflammation in patients with psoriasis.22 23 In this PsO cohort, as already described in patients with psoriasis without musculoskeletal complaints, age was associated with active synovitis.9 24

Furthermore, the positive correlation found between US enthesitis and non-smoking status seems to suggest a relationship between smoking status and the development of sonographically detected entheseal inflammation. This observation supports the apparent paradox in which smoking could favour psoriasis but could be inversely associated with PsA among patients with psoriasis.13 25

The limitations of this study included the small numbers and relative short follow-up, but the findings are in agreement with previous literature.7 18 Moreover, the evaluation of arthralgia as present versus absent without reporting the anatomical sites of arthralgia will need to be addressed in future studies. These findings need replication in bigger cohorts, also with the aim of constructing a predictive model for development of PsA, which was not feasible due to the low number of events (ie, PsA development) and the wide range of possible clinical and US predictors. In conclusion, these preliminary results identified and stratified, using both clinical and ultrasound, a subgroup of patients with psoriasis more prone to develop PsA, that is, PsOAr, in which a strict rheumatological monitoring or disease interception with psoriasis directed therapy could be envisaged.

Footnotes

Contributors: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the version published: all authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted according to a protocol approved by the Local Ethical Committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Ritchlin C. Psoriatic disease--from skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2007;3:698–706. 10.1038/ncprheum0670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ogdie A. The preclinical phase of PSA: a challenge for the epidemiologist. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1481–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, et al. . Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:233–9. 10.1002/art.24172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Steenbergen HW, Aletaha D, Beaart-van de Voorde LJJ, et al. . EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:491–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kleyer A, Krieter M, Oliveira I, et al. . High prevalence of tenosynovial inflammation before onset of rheumatoid arthritis and its link to progression to RA—A combined MRI/CT study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:143–50. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zabotti A, Finzel S, Baraliakos X, et al. . Imaging in the preclinical phases of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Jul 2019]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. . The development of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:622–9. 10.1002/art.39973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zabotti A, Bandinelli F, Batticciotto A, et al. . Musculoskeletal ultrasonography for psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis patients: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology 2017;56:1518–32. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zuliani F, Zabotti A, Errichetti E, et al. . Ultrasonographic detection of subclinical enthesitis and synovitis: a possible stratification of psoriatic patients without clinical musculoskeletal involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:593–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tinazzi I, McGONAGLE D, Biasi D, et al. . Preliminary evidence that subclinical enthesopathy may predict psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:2691–2. 10.3899/jrheum.110505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gisondi P, Tinazzi I, El-Dalati G, et al. . Lower limb enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without clinical signs of arthropathy: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:26–30. 10.1136/ard.2007.075101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Savage L, Goodfield M, Horton L, et al. . Regression of peripheral subclinical enthesopathy in therapy-naive patients treated with ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a fifty-two-week, prospective, open-label feasibility study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:626–31. 10.1002/art.40778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scher JU, Ogdie A, Merola JF, et al. . Preventing psoriatic arthritis: focusing on patients with psoriasis at increased risk of transition. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019;15:153–66. 10.1038/s41584-019-0175-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. . Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zabotti A, Piga M, Canzoni M, et al. . Ultrasonography in psoriatic arthritis: which sites should we scan? Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1537–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Canzoni M, Piga M, Zabotti A, et al. . Clinical and ultrasonographic predictors for achieving minimal disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis: the upstream (ultrasound in psoriatic arthritis treatment) prospective observational study protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021942 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Balint PV, Terslev L, Aegerter P, et al. . Reliability of a consensus-based ultrasound definition and scoring for enthesitis in spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: an OMERACT us initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1730–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faustini F, Simon D, Oliveira I, et al. . Subclinical joint inflammation in patients with psoriasis without concomitant psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2068–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacques P, Lambrecht S, Verheugen E, et al. . Proof of concept: enthesitis and new bone formation in spondyloarthritis are driven by mechanical strain and stromal cells. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:437–45. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tinazzi I, McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, et al. . ‘Deep Koebner’ phenomenon of the flexor tendon-associated accessory pulleys as a novel factor in tenosynovitis and dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:922–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McGonagle D, Tan AL, Watad A, et al. . Pathophysiology, assessment and treatment of psoriatic dactylitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019;15:113–22. 10.1038/s41584-018-0147-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ash ZR, Tinazzi I, Gallego CC, et al. . Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:553–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aydin SZ, Castillo-Gallego C, Ash ZR, et al. . Ultrasonographic assessment of nail in psoriatic disease shows a link between onychopathy and distal interphalangeal joint extensor tendon enthesopathy. Dermatology 2012;225:231–5. 10.1159/000343607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naredo E, Moller I, de Miguel E, et al. . High prevalence of ultrasonographic synovitis and enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis: a prospective case-control study. Rheumatology 2011;50:1838–48. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eder L, Shanmugarajah S, Thavaneswaran A, et al. . The association between smoking and the development of psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:219–24. 10.1136/ard.2010.147793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wakefield RJ, Balint PV, Szkudlarek M, et al. . Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2485–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scheel AK, Hermann K-GA, Kahler E, et al. . A novel ultrasonographic synovitis scoring system suitable for analyzing finger joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2005;52:733–43. 10.1002/art.20939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Szkudlarek M, Court-Payen M, Jacobsen S, et al. . Interobserver agreement in ultrasonography of the finger and toe joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2003;48:955–62. 10.1002/art.10877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. D'Agostino M-A, Boers M, Wakefield RJ, et al. . Exploring a new ultrasound score as a clinical predictive tool in patients with rheumatoid arthritis starting abatacept: results from the appraise study. RMD Open 2016;2:e000237 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammer HB, Iagnocco A, Mathiessen A, et al. . Global ultrasound assessment of structural lesions in osteoarthritis: a reliability study by the OMERACT ultrasonography group on scoring cartilage and osteophytes in finger joints. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:402–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naredo E, D'Agostino MA, Wakefield RJ, et al. . Reliability of a consensus-based ultrasound score for tenosynovitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1328–34. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hirji Z, Hunjun JS, Choudur HN. Imaging of the Bursae. J Clin Imaging Sci 2011;1:22 10.4103/2156-7514.80374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gutierrez M, Filippucci E, Salaffi F, et al. . Differential diagnosis between rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: the value of ultrasound findings at metacarpophalangeal joints level. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1111–4. 10.1136/ard.2010.147272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zabotti A, Salvin S, Quartuccio L, et al. . Differentiation between early rheumatoid and early psoriatic arthritis by the ultrasonographic study of the synovio-entheseal complex of the small joints of the hands. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:459–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Balint PV, Kane D, Wilson H. Ultrasonography of entheseal insertions in the lower limb in spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:905–10. 10.1136/ard.61.10.905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]