Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common connective tissue disorder affecting the synovial joints. In patients with RA, involvement of the lungs occurs in 30%–40% of cases while pleural effusions occur in only 3%–5%. However, the majority of RA-associated pleural effusions are small, unilateral and asymptomatic. We present a case of massive bilateral pleural effusions in a patient with established rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan syndrome). Interestingly, the pleural effusion occurred following recent treatment for minimal change disease and atrial fibrillation.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, respiratory medicine

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disorder that commonly affects synovial joints. In certain susceptible individuals, exposure to coal, silica and/or asbestos can also lead to rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan syndrome).1 2 Although Caplan syndrome by itself generally does not require treatment, management is directed towards treating the extrapulmonary manifestations of RA.

In patients with RA, 30%–40% have associated lung disease, most commonly involving the interstitium, airways or pleura.3 The prevalence of pleural involvement is 50%–70% in autopsy studies, but symptomatic RA-associated pleural effusions occur in only 3%–5% of patients.4 5 While a few case reports have reported on pleural effusions in patients with pulmonary nodules, the majority of these pulmonary nodules are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally during or after thoracentesis.6–10 To our knowledge, this is the first case of a patient with well-established Caplan syndrome who developed massive bilateral pleural effusions >20 years after his initial diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old man with a history of RA complicated by Caplan syndrome (biopsy-proven silico-anthracotic pulmonary nodules), new-onset atrial fibrillation of 2-week duration and minimal change disease recently treated with steroids was admitted for persistent chest pain and shortness of breath. He described the pain as burning, substernal, non-radiating and worse on deep inspiration but denied any fever, chills, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or leg swelling. When lying down, the pain localised to his mid-lower back. Family history was negative for autoimmune diseases. He had no significant alcohol or smoking history. Interestingly, he had worked in shipyards during his military service and as a porter for >20 years thereafter.

While in the emergency department, he was afebrile, tachypneic, tachycardic and normotensive saturating 95% on 2 L nasal cannula. His cardiovascular exam revealed an irregularly irregular rhythm. Lung exam revealed diminished breath sounds in the left lung base. Extremities showed multiple RA nodules on extensor surfaces of his forearms. The remainder of his exam was unremarkable.

Investigations

Routine serum chemistries and complete blood count were largely within normal limits but an electrocardiogram revealed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. CT angiography was negative for pulmonary embolus and revealed a moderate-sized left pleural effusion, small right pleural effusion and multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules (consistent with his previous diagnosis of Caplan syndrome). He was started on apixaban and intravenous metoprolol with gradual improvement in his chest pain and control of his heart rate.

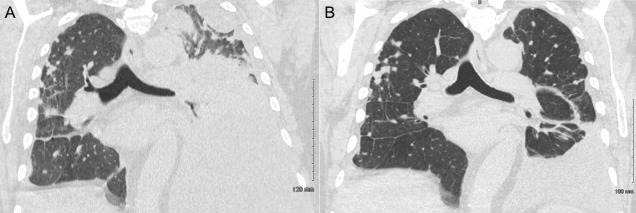

On hospital day 2, he still appeared dyspneic. Due to concern for infection, blood and urine cultures were drawn. His urine culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae for which he was started on ceftriaxone for coverage of a urinary tract infection and potential pneumonia. Overnight on hospital day 3, he acutely worsened and developed a new oxygen requirement with oxygen desaturations of 85%–95% on 5 L nasal cannula and decreased left lower lung sounds and increased mid-lower back pain. Laboratory studies revealed an elevated sedimentation rate (70 mm/hour, ref: 0–22 mm/hour) and highly elevated C-reactive protein (295 mg/L, ref: <3 mg/L). Repeat CT scan of the chest revealed an increased left-sided pleural effusion, mediastinal shift towards the right, complete consolidation of the left lower lobe with partial consolidation of the left upper lobe and a small right pleural effusion with associated atelectasis (figure 1A). At this point, rheumatology was consulted for assistance with management.

Figure 1.

Thoracentesis and intravenous steroids led to a significant reduction in RA-associated pleural effusion burden. (A) Chest CT before treatment revealed a large, multiloculated left pleural effusion occupying the majority of the left hemithorax with mediastinal shift towards the right and a small right pleural effusion. (B) Chest CT after thoracentesis and three doses of intravenous methylprednisolone 125 mg administered once daily revealed a marked reduction in the size of the left pleural effusion with a persistent small right-sided pleural effusion. RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

On hospital day 5, thoracentesis removed 2 L of straw-coloured pleural fluid and a pigtail catheter was placed in the pleural space to drain residual fluid. Pleural fluid analysis revealed many polymorphonuclear cells without any organisms, 13.8 x 109 cells/L (97% neutrophils), glucose <1 mmol/L, protein 45 g/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 2514 IU/L, cholesterol 2.5 mmol/L, rheumatoid factor 96 IU/mL (ref: <16 IU/mL); serum levels revealed glucose 6.8 mmol/L, protein 55 g/L, LDH 182 IU/L, cholesterol 2.6 mmol/L (table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of RA-associated pleural fluid revealed an exudative effusion

| Pleural fluid | Serum fluid | Ratio P/S | |

| LDH (IU/L) | 2514 (50–95) | 182 (100–190) | 13.8 (<0.6) |

| Protein (g/L) | 45 (10–20) | 55 (60–80) | 0.8 (<0.5) |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.5 (<1.6*) | 2.6 (<5.2) | – |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | <1 (4.1–5.9) | 6.8 (4.1–5.9) | – |

| Rheum factor (IU/L) | 96 (<16) | (<16) | – |

*Normal reference ranges in parentheses.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Differential diagnosis

The first step in the evaluation of patients with a pleural effusion is to determine if the effusion is transudative or exudative.11 In our case, the effusion was exudative by Light’s criteria.12 Most exudative effusions in the USA are caused by pneumonia, cancer or pulmonary embolism.11 Our patient had a negative CT angiography, which effectively ruled out pulmonary embolism. Moreover, our patient was afebrile, normotensive and had a normal leucocyte count, which lowered our suspicion for an infectious aetiology such as pneumonia. Since our suspicion for pneumonia and pulmonary embolism were lower on our differential, that left us considering cancer versus other rare aetiologies.

Given our patient’s extensive rheumatological history and work-related exposures from working in shipyards in the military, rheumatoid-associated pleural effusion and malignant pleural effusion were high on our differential. Typically, the pleural effusion seen in rheumatoid-associated pleural effusion has exudative features with a high rheumatoid factor titer, cholesterol (>1.7 mmol/L) and LDH (>700 IU/L) along with low glucose (<3.3 mmol/L) and pH levels (<7.2).13 In our case, pleural fluid analysis revealed a high rheumatoid factor titer; cytology did not reveal any evidence of malignancy. These laboratory features taken together confirmed our diagnosis of rheumatoid-associated pleural effusion.

Treatment

Thoracentesis of 2 L of pleural fluid was both diagnostic and therapeutic. In addition to thoracentesis, apixaban was withheld and the patient was treated with methylprednisolone 125 mg intravenous for 3 days (first dose started on hospital day 4).

Supplemental oxygen was removed on hospital day 6 and his oxygen-saturation remained >90% on room air for >24 hours. Bedside ultrasound on hospital day 7 revealed residual pleural effusions but he remained medically and haemodynamically stable.

On hospital day 8, final chest CT revealed a significant reduction in the left-sided pleural fluid effusion (figure 1B). He was later discharged the same day on prednisone 60 mg/day with a planned taper until his outpatient follow-up appointment with rheumatology.

Outcome and follow-up

At 6 months post-thoracentesis and methylprednisolone therapy, the patient has been doing well and has been living comfortably at his retirement home. He is being followed regularly as an outpatient by his rheumatologist who notes that his RA has been well controlled. There has been no evidence of recurrence of his pleural effusions.

Discussion

Although RA-associated pleural effusions are found in 50%–70% of autopsy studies, effusions that cause symptoms are rare and occur in only 3%–5% of patients (eg, pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea).4 14 Moreover, some studies have demonstrated that pleurisy and pleural effusions tend to occur as a late manifestation of RA, particularly in patients who have associated rheumatoid nodules, which interestingly, our patient had (Caplan syndrome).15

A few case reports have been published on RA-associated pleural effusions describing the characteristics of the effusion, clinical manifestations of the disease and steroid-based therapies, but to our knowledge, this is the first report of RA-associated pleural effusion occurring in a patient with previously established Caplan syndrome.13 16–18 Moreover, the pleural effusion developed in the setting of recent steroid withdrawal and atrial fibrillation.

Pleural effusion in the context of atrial fibrillation and beta-blocker administration is a well-established phenomenon.19 However, in this case, the pleural effusion is clearly favourable of a rheumatoid aetiology. Thus, prompt thoracentesis and treatment with intravenous steroids is of the utmost importance while awaiting definitive long-term therapy.

Learning points.

Massive pleural effusions can occur in patients with rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan syndrome), even if they have been stable/asymptomatic for many years prior.

Recent withdrawal of steroids and/or atrial fibrillation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may potentially trigger worsening of rheumatoid-associated pleural effusions.

Patients with suspected RA-associated pleural effusion should be evaluated via chest imaging and diagnostic/therapeutic thoracentesis followed by serum and pleural fluid analysis and cytology.

Analysis and cytology of RA-associated pleural effusions will reveal (1) an exudative effusion by Light’s criteria, (2) glucose <3.3 mmol/L, (3) elevated lactate dehydrogenase >700 U/L, (4) high rheumatoid factor titers and (5) inflammatory pleural fluid with a neutrophilic predominance.

Acute management with high-dose intravenous steroids and thoracentesis can lead to rapid symptomatic improvement; a gradual steroid-taper can be utilised while awaiting definitive long-term RA therapy with biologics.

Footnotes

Twitter: @PDittyMD

Contributors: YW conceived of the presented idea. YW and PCD contributed to the design, drafting and revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. YW and PCD agree to be accountable for the manuscript and to ensure that all questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of the manuscript are investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Schreiber J, Koschel D, Kekow J, et al. Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan's syndrome). Eur J Intern Med 2010;21:168–72. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Capitani EM, Schweller M, Silva CMda, et al. Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan's syndrome) with a classical presentation. J Bras Pneumol 2009;35:942–6. 10.1590/s1806-37132009000900017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischer A, du Bois R. Interstitial lung disease in connective tissue disorders. Lancet 2012;380:689–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61079-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shaw M, Collins BF, Ho LA, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:1–16. 10.1183/09059180.00008014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jurik AG, Davidsen D, Graudal H. Prevalence of pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship to some characteristics of the patients. A radiological and clinical study. Scand J Rheumatol 1982;11:217–24. 10.3109/03009748209098194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emmungil H, Yıldız F, Gözükara MY, et al. Rheumatoid pleural effusion with nodular pleuritis. A rare presentation of rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol 2015;74:72–4. 10.1007/s00393-014-1462-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tserkezoglou A, Metakidis S, Papastamatiou-Tsimara H, et al. Solitary rheumatoid nodule of the pleura and rheumatoid pleural effusion. Thorax 1978;33:769–72. 10.1136/thx.33.6.769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chabalko JJ. Acute rheumatoid pleurisy with effusion and demonstration of a rheumatoid nodule in the pleura. Del Med J 1984;56:649–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kimura K, Toyama K, Yoshida M, et al. [Rheumatoid nodule diagnosed by thoracoscopy using flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 1998;36:994–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones JS. An account of pleural effusions, pulmonary nodules and cavities attributable to rheumatoid disease. Br J Dis Chest 1978;72:39–56. 10.1016/0007-0971(78)90006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Porcel JM, Light RW. Diagnostic approach to pleural effusion in adults. Am Fam Physician 2006;73:1211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, et al. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med 1972;77:507–13. 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balbir-Gurman A, Yigla M, Nahir AM, et al. Rheumatoid pleural effusion. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006;35:368–78. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alunno A, Gerli R, Giacomelli R, et al. Clinical, epidemiological, and histopathological features of respiratory involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/7915340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bouros D, Pneumatikos I, Tzouvelekis A. Pleural involvement in systemic autoimmune disorders. Respiration 2008;75:361–71. 10.1159/000119051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chou C-W, Chang S-C. Pleuritis as a presenting manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis: diagnostic clues in pleural fluid cytology. Am J Med Sci 2002;323:158–61. 10.1097/00000441-200203000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corcoran JP, Ahmad M, Mukherjee R, et al. Pleuro-pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Respir Care 2014;59:e55–9. 10.4187/respcare.02597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stout J, Hayes D, Rojas-Moreno C, et al. Rheumatoid pleural effusions and trapped lung: an uncommon complication of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hosp Med 2015;7. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hooper C, Lee YCG, Maskell N, et al. Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults: British thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax 2010;65 Suppl 2:ii4–17. 10.1136/thx.2010.136978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]