Abstract

Transcriptional regulation of Laminin expression during embryogenesis is a key step required for proper ECM assembly. We show, that in Drosophila the Laminin B1 and Laminin B2 genes share expression patterns in mesodermal cells as well as in endodermal and ectodermal gut primordia, yolk and amnioserosa. In the absence of the GATA transcription factor Serpent, the spatial extend of Laminin reporter gene expression was strongly limited, indicating that Laminin expression in many tissues depends on Serpent activity. We demonstrate a direct binding of Serpent to the intronic enhancers of Laminin B1 and Laminin B2. In addition, ectopically expressed Serpent activated enhancer elements of Laminin B1 and Laminin B2. Our results reveal Serpent as an important regulator of Laminin expression across tissues.

Subject terms: Extracellular matrix, Morphogenesis, Gene regulation

Introduction

Laminins are heterotrimeric proteins found in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and are major components of all basement membranes (BMs). These proteins self-assemble into a cell-associated network and interact with cell-surface molecules such as integrin receptors and other ECM components. Laminin heterotrimers are composed of three distinct subunits (α, β, and γ) that yield a cross-shaped structure. The Drosophila genome encodes two distinct α-subunits (Laminin A, LanA; Laminin Wing blister, LanWb), as well as one β- (Laminin B1, LanB1) and one γ-subunit (Laminin B2, LanB2)1,2. Each heterotrimer is formed by initial dimerization of ß- and γ-subunits via disulfide-bonding and subsequent incorporation of α-subunits, followed by the secretion and binding of the final receptor at the cell surface3–6. There, Laminins perform several functions in higher organisms, ranging from cell adhesion to migration processes during development7–9. Experiments using mammalian cell culture revealed that α-subunits can be secreted independently, whereas the secretion of β/γ proteins needs simultaneous expression of both10, indicating a common regulatory mechanism for them. Moreover, loss of LanB1 and LanB2 pointed to a dependency of both proteins for heterotrimeric Laminin-secretion in Drosophila7,8,11.

While Laminins and their roles in BM self-assembly are well investigated in mammalian cell culture, the regulation of this process is poorly understood. With respect to the single ß-/γ-subunits, Drosophila seems to be a suitable model to study Laminin gene regulation in vivo, since mammalian genomes contain twelve distinct Laminin subunits12. Due to the strong expression of Laminins in Drosophila hemocytes and fat body cells, as well as the observation of severe endodermal defects in Laminin mutant embryos, we focused our analysis on the main transcriptional regulator of these tissues in Drosophila, the GATA-transcription factor Serpent (Srp, dGATAb). Srp is involved in the differentiation of several tissues derived from different germ layers, such as mesoderm derived fat body and blood cells, endodermal midgut primordia, and the amnioserosa13. Notably, these are tissues in which the Laminin subunits B1 and B2 also play an important role during morphogenesis7,8,14.

Results

Reporter gene expression for LanB1 and LanB2

During late embryonic stages, most of the Laminin proteins present in the ECM of tissues are synthesized and secreted by hemocytes and the fat body. However, during early embryonic development, Laminin expression is not detected in hemocytes or the fat body, indicating that during this stage Laminin proteins are produced by the tissues themselves (Figs 1 and 2). We selected the Drosophila genes Laminin B1 and Laminin B2, encoding the unique Laminin ß- and γ-subunit, owing to their postulated co-expression7,8,15,16, to characterize gene expression of early embryonic tissues and late embryonic secretion. Both genes show small upstream (upstream enhancer, UE) and large intronic (intronic enhancer, IE) enhancers. Bioinformatic analysis of the large first introns revealed several conserved regions in these enhancers, indicating the presence of cis-regulatory modules (CRMs). Only LanB2 displayed an additional small conserved region in the corresponding UE. Therefore, we generated reporter constructs by fusing the derived CRMs of both Laminin genes to GFP, analyzed the derived tissue-specific expression and compared it to the described mRNA and protein distribution (Supplementary Table S1 and Figs 1 and 2).

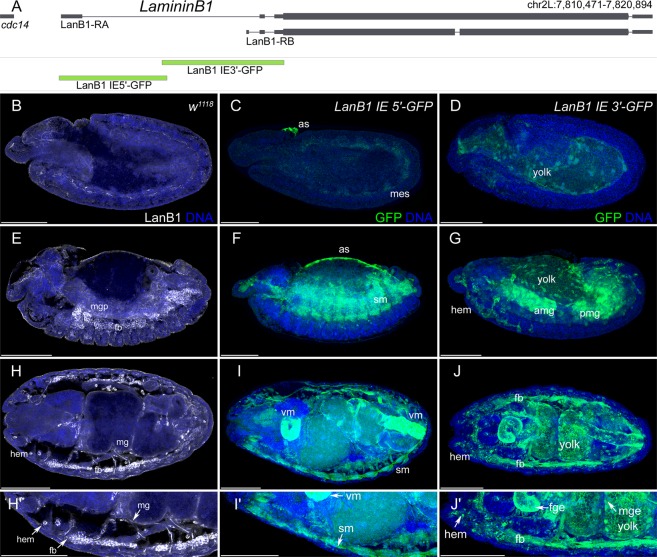

Figure 1.

Embryonic expression of LanB1 reporter gene constructs. (A) Schematic representation of the LanB1 genetic region and the derived reporter constructs. (B,E,H,H′) Protein distribution of LanB1 (white) in white1118 (w1118) embryos. (C,F,I,I′) Reporter gene expression (green) of the LanB1 IE 5′-GFP construct. (D,G,J,J′) Reporter gene expression (green) of the LanB1 IE 3′-GFP construct. (B–D) Embryos at stage 11 (lateral view), (E–G) embryos at stage 14 (lateral view), (H–J) embryos at stage 16 (dorsal view) and (H′-J′) higher magnification of the embryos in (H–J). (B-J′) DNA staining in blue. Abbr.: as: amnioserosa, amp and pmg: anterior and posterior midgut primordia, fb: fat body, fge: foregut epithelium, hem: hemocytes, mes: mesoderm, mge: midgut epithelium, sm: somatic muscles, vm: visceral muscles. Scale Bars = 100 µm.

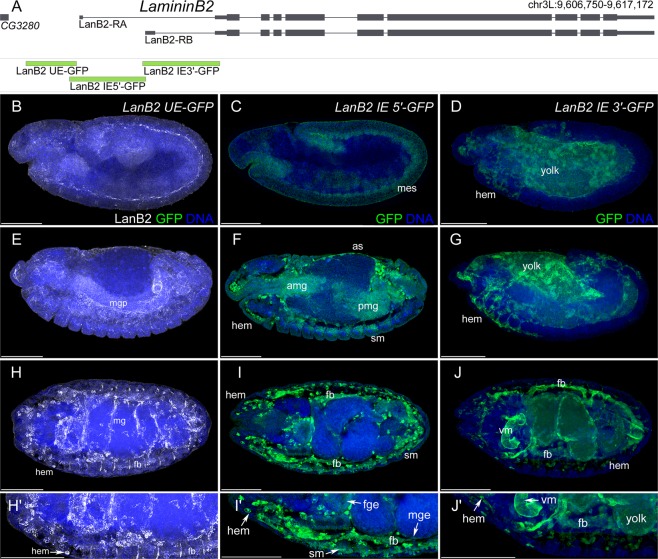

Figure 2.

Embryonic expression of LanB2 reporter gene constructs. (A) Schematic representation of the LanB2 genetic region and the derived reporter constructs. (B,E,H,H′) Reporter gene expression (green) of the LanB2 UE-GFP construct and LanB2 protein distribution (white). (C,F,I,I′) Reporter gene expression (green) of the LanB2 IE 5′-GFP construct. (D,G,J,J′) Reporter gene expression (green) of the LanB2 IE 3′-GFP construct. (B–D) Embryos at stage 11 (lateral view), (E–G) embryos at stage 14 (lateral view), (H–J) embryos at stage 16 (dorsal view) and (H′–J′) higher magnification of the embryos in (H–J). (B–J′) DNA staining in blue. Abbr.: as: amnioserosa, amp and pmg: anterior and posterior midgut primordia, fb: fat body, fge: foregut epithelium, hem: hemocytes, mes: mesoderm, mge: midgut epithelium, sm: somatic muscles, vm: visceral muscles. Scale Bars = 100 µm.

The IE 5′ constructs of both Laminins revealed expression in the early mesoderm as well as in the amnioserosa (LanB1 IE 5′ in Fig. 1C,F and LanB2 IE 5′ in Fig. 2C,F, amnioserosa not visible in 2 C). At the end of embryogenesis, expression was found in the mesoderm derived somatic muscles (LanB1 IE 5′ in Fig. 1I,I′ and LanB2 IE 5′ in Fig. 2I,I′) and the visceral muscles (LanB1 IE 5′ in Fig. 1I,I′ and LanB2 IE 3′ in Fig. 2J,J′). Additional expression in endodermal midgut primordia was displayed for the LanB1 IE 3′ (Fig. 1G) as well as LanB2 IE 5′ (Fig. 2F) construct.

Laminin reporter gene expression in hemocytes and fat body cells could be detected from early differentiation and was observed for the LanB2 IE 5′ construct (LanB2 IE 5′ in Fig. 2F,I,I′) as well as in both 3′ constructs (LanB1 IE 3′ in Fig. 1G,J,J′ and LanB2 IE 3′ in Fig. 2G,J,J′). Both Lan IE 3′ constructs showed further expression in some cells of the peripheral nervous system, in the dorsal median cells (both not shown) and the yolk (LanB1 IE 3′ in Fig. 1D,G,J,J′ and LanB2 IE 3′ in Fig. 2D,G,J,J′). The LanB1 IE 3′ construct displayed additional expression in salivary glands and Malpighian tubules (both not shown). Although the LanB2 UE region contains a small conserved region (Supplementary Fig. S2), the analysis revealed no embryonic reporter gene expression, indicating no CRMs for embryonic expression in this UE. In summary, the reporter constructs reflect the complete known embryonic expression of LanB1 and LanB2 (Supplementary Table S1), so that all CRMs promoting embryonic expression should also be included.

The comparative Laminin B1 and B2 protein distribution appeared initially in a layer between the mesoderm and ectoderm of embryos at the fully elongated germ band stage and was continued in the somatic and visceral mesoderm as well as in the endodermal midgut primordia. At the end of embryogenesis, LanB1 and LanB2 covered most tissues and were strongly secreted by fat body and blood cells (LanB1 in Fig. 1H,H′ and LanB2 in Fig. 2H,H′7,8). In conclusion, every tissue in which LanB1 and LanB2 could be detected at the end of embryogenesis seemed to express Laminin itself for its own initial BM assembly.

In silico prediction of putative Srp-binding sites in LanB1 and LanB2

In order to identify transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, we searched for potential regulators controlling LanB1 and LanB2 expression using transcription factor binding profile databases17,18. Conservation scores (PhastCons datasets of 14 insect species)19 were used to identify and eliminate the false positive transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) enriched in the non-coding regions, based on the assumption that binding sites essential for Laminin expression are strongly conserved across insect phylogeny. We found an overrepresentation of potential binding sites for Srp20,21 in the intronic enhancers (IE) of LanB1 and LanB2, and one additional hit in the upstream enhancer (UE) of LanB2. These binding sites showed strong conservation scores and were located partially in conserved regions, but also at loci, where only the binding sites displayed peaks of conservation (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2).

LanB1 and LanB2 reporter gene expression in srp mutant background and upon tissue-specific srp knockdown

To test whether expression of LanB1 and LanB2 depends on the GATA-factor Serpent (Srp), we analyzed Laminin reporter gene expression in hypomorphic srpneo45 mutant embryos, in which only the differentiation of hemocytes is affected, and in srp3 null mutant embryos13,22 (Fig. 3).

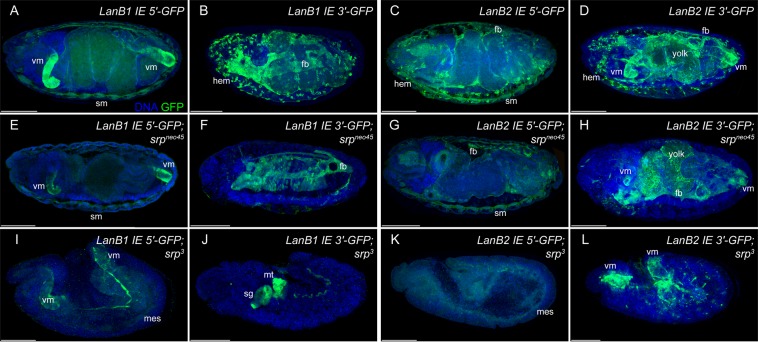

Figure 3.

Reporter gene expression in srp mutant background. Reporter gene expression of LanB1 and LanB2 intronic enhancer regions (A–D) displayed in the genetic background of hypomorphic (srpneo45) (E–H) and amorphic (srp3) (I–L) srp alleles. Abbr.: fb: fat body, fg: foregut, hem: hemocytes, hg: hindgut, mes: mesoderm, mt: Malpighian tubules, sg: salivary glands, sm: somatic muscles, vm: visceral muscles. Scale bars = 100 µm.

In srpneo45 mutants, hemocytes were missing and within reporter gene expression of hemocytes, whereas expression in all other tissues was still observed (Fig. 3E–H). In contrast, in srp3 embryos the fat body and the amnioserosa remain undifferentiated and the hemocytes as well as endoderm primordia were missing13,23–26. Only residual reporter gene expression could be detected in the progenitor cells of the visceral and somatic mesoderm (Fig. 3I,K,L), in some cells of the PNS (Fig. 3L), and in the rudiments of salivary glands and Malpighian tubules (Fig. 3J). This remaining reporter gene expression in srp mutant embryos revealed additional srp-independent Laminin regulation.

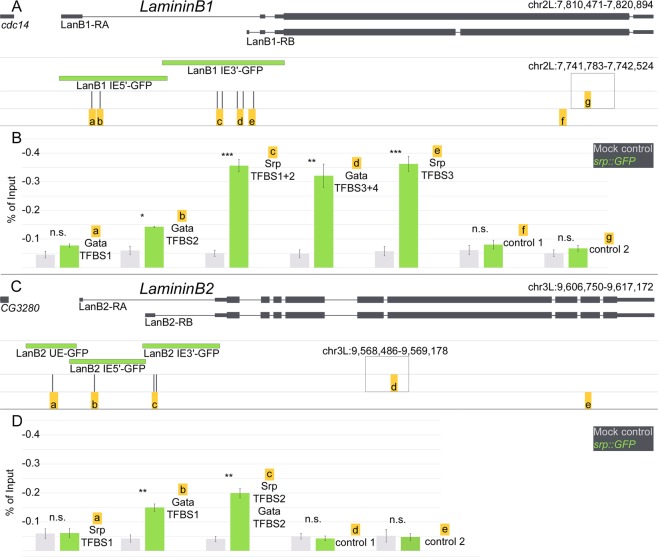

Srp binds directly to the intronic enhancers of LanB1 and LanB2

The experiments described above indicate a potential regulatory role of Srp for LanB1 and LanB2 expression. In order to test a direct binding ability of Srp to LanB1/LanB2, we performed ChIP analysis followed by subsequent qPCR. For LanB1 expression, we analyzed the Srp enrichment at five genomic regions, with seven predicted GATA/Srp-binding sites (Supplementary Fig. S1, with marked genomic location). At the locus, represented by the LanB1 IE 5′ construct, we checked two GATA-transcription factor binding sites (GATA-TFBS 1 and GATA-TFBS 2) for enrichment. The results showed only a slight increase of Srp compared to the control (Fig. 4B; GATA-TFBS 1: control 0.05% of input (referred hereafter as %), Srp::GFP 0.08%; GATA-TFBS 2: control 0.03%, Srp::GFP 0.14%), whereas the enrichment of Srp at the locus represented by LanB1 IE 3′ was considerably higher than that in the control (Fig. 4B Srp-TFBS 1 + 2: control 0.03%, Srp::GFP 0.36%; GATA-TFBS 3 + 4: control 0.02%, Srp::GFP 0.32%; Srp-TFBS 3: control 0.03%, Srp::GFP 0.36%). The negative controls demonstrated that control primers amplify ChIP-DNA with a slight variation, but do not show enrichment over input (Fig. 4B control 1: control 0.06%, Srp::GFP 0.08%; control 2: control 0.05%, Srp::GFP 0.07%). Taken together, these results display a weak enrichment of Srp for the GATA-TFBS 2, located at LanB1 IE 5′, and a high significant enrichment of Srp in the LanB1 IE 3′ region. This was also evident in the context of reporter gene expression of these constructs (Fig. 1), because LanB1 IE 5′ display Srp-regulated Laminin expression only in the amnioserosa (Fig. 1C,F). This tissue persists just in the first half of embryogenesis and undergoes programmed cell death thereafter25. Therefore, just a small fraction of cross-linked cells could influence the enrichment of Srp in this approach. In contrast, LanB1 IE 3′ showed a high Srp enrichment and strong reporter gene expression in the endoderm, hemocytes and fat body, whose determination and differentiation depends on Srp activation (Figs 1 and 3).

Figure 4.

ChIP-qPCR reveals Srp-binding sites in the CRMs of LanB1 and LanB2. (A,C) Schematic representation of (A) LanB1 and (C) LanB2 transcripts, derived reporter constructs (green) and predicted GATA/Srp-binding sites with amplified regions beneath (yellow boxes with lowercase letters). The higher boxes indicate additionally amplified control regions outside of the displayed genomic loci. (B,D) qPCR amplified DNA of ChIP experiments with srp::GFP (green) and mock control (white1118, gray) genotypes illustrated as percentage of input. Samples are generated as independent biological replicates (n = 3). Welch’s two-sample t-test with adjusted p-values, ***p < 0.001, **p = 0.005, non-significant (n.s.) = p > 0.05. Mean ± SEM.

For analysis of LanB2 regulation, we investigated three genomic loci, including four potential GATA- and Srp-binding sites (Supplementary Fig. S2, with marked genomic location). The first Srp-binding site is located in the upstream enhancer (Srp-TFBS 1), one is found in the 5′ region of the intronic enhancer (GATA-TFBS 1), and two potential binding sites are located in the 3′ region of the intronic enhancer (Srp-TFBS 2 and GATA-TFBS 2; Fig. 4C). The ChIP analysis detected no enrichment of Srp in the upstream enhancer (Srp-TFBS 1: control 0.06%, Srp::GFP 0.06%), whereas both loci in the intronic enhancer showed a significant enrichment of Srp protein (GATA-TFBS 1: control 0.02%, Srp::GFP 0.15% for LanB2 IE 5′; Srp-TFBS 2 + GATA-TFBS 2: control 0.03%, Srp::GFP 0.20% for LanB2 IE 3′). These data are in agreement with the previous reporter gene analysis (Fig. 2), as we did not find any reporter gene expression of LanB2 UE in the embryo, while LanB2 IE 5′ and LanB2 IE 3′ displayed Srp-dependent Laminin expression patterns (Fig. 2).

Taken together, the strong Srp enrichment in both regions of LanB2 intronic enhancer constructs and the strong enrichment found in LanB1 IE 3′ indicate that hemocyte and fat body regulation show the strongest effect for Srp binding. In addition, the enrichment in the LanB1 IE 5′ region indicates a regulatory role of Srp for Laminin expression in the amnioserosa.

Ectopically expressed srp activates Laminin reporter gene expression

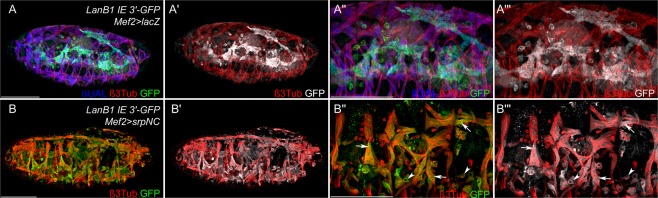

To test whether Srp is able to induce LanB1 and LanB2 expression, we expressed srp27 ectopically in all muscle cells using the mef2-GAL4 driver in the background of our LanB1 IE 3′ (Fig. 5) and LanB2 IE 3′ (Supplementary Fig. S3) constructs, which displayed no myogenic expression (Figs 1J,J′ and 2J,J′). At the end of embryogenesis, the somatic musculature builds a specific stereotypical pattern. These myotubes were characterized by persistent mef2 expression (revealed by mef2-GAL4 driven UAS-lacZ, Fig. 5A,A″) and a characteristic cell shape in control animals (Fig. 5A,A″′). LanB1 IE 3′ GFP reporter gene expression in control embryos was restricted to fat body and hemocytes, whereas ectopically expressed srp induced reporter activity was detected in several somatic muscles (arrows, Fig. 5B″,B″′) and unfused myoblasts (Fig. 5B″,B″′), displaying ectopic activation of CRMs from LanB1 IE3′. Similar results were obtained with the LanB2 IE 3′ GFP reporter (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 5.

Myogenic srp expression leads to ectopic Laminin reporter activation and disrupted myogenesis. (A,A″′) Control animals show GFP reporter gene expression of LanB1 IE 3′ (A,A″ in green, A′,A″′ white) and Mef2-GAL4 driven UAS-lacZ activity (A,A″ blue) with anti-ß3Tubulin as muscles marker (red). (B,B″′) Ectopic expression of UAS-srpNC with Mef2-GAL4 is sufficient for Laminin reporter gene activation in somatic muscles (arrows) and unfused myoblasts (arrowheads), leading to disrupted myogenesis. GFP reporter gene expression (B,B″ green; B′,B″′ white) and anti-ß3Tubulin (red). Scale bars = 100 µm.

This gain-of-function experiments demonstrated that srp expression is sufficient for LanB1 and LanB2 enhancer activation. Interestingly, ectopic expression of srp led to a massive disruption of myoblast fusion, reminiscent of several myoblast fusion mutants28–31. So even at the end of morphogenesis, unfused myoblasts and disarranged fused muscles were clearly visible all over the somatic and the visceral mesoderm (Fig. 5B,B″′), indicating an important role of tissue-specific Srp expression and subsequent gene regulation.

Discussion

Laminins are crucial components for BM construction. Our results indicate a common tissue-specific expression of LanB1 and LanB2. We also identified cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) for this tissue-specific expression. The expression of the Laminin β/γ subunits is essential for subsequent di- and trimerization, and reflects the onset of earliest ECM assembly.

Laminins are expressed in all germ layers (this study7,8,15,16) and an initial Laminin network exists prior to further ECM component secretion (this study32), which is responsible for complex developmental processes such as cell migration and organogenesis7,8,33,34, suggesting complex regulatory mechanisms. While the loss of Laminin reporter gene expression in srp mutants (Fig. 3) could also be explained by lack of differentiation of these tissues, ectopic activation of Srp in muscle cells (Fig. 5) indicates a regulatory role for Laminin expression. Based on the identified CRMs (Fig. 4), our results indicate that Srp the main GATA-transcription factor in Drosophila, act as Laminin regulator in distinct tissues and germ layers (Figs 1, 2, 5). In this context, it seems evident that Srp, owing to its expression in multiple tissues, is also able to regulate Laminin expression in a variety of tissues.

While, in Drosophila, Srp is the single most important GATA-factor for development, in vertebrates, multiple GATA-orthologues play important and tissue-specific roles during differentiation24. In this context, it seems interesting that Srp binds at the predicted GATA-TFBS (b in Fig. 4B,D), as this binding site was found with a PWM for mouse GATA1. The role of Srp for hemocyte/blood cell differentiation may be conserved throughout vertebrate development35. Therefore, it appears that there is a Srp-binding site closely related to the vertebrate GATA1-TFBS, while the Srp-TFBS reported here is similar to the vertebrate GATA4- and GATA6-TFBS17.

In cultured mouse embryonic stem cells, forced vertebrate GATA4 and GATA6 expression strongly enhances and silences laminin-1 production, respectively36,37. These experiments reveal no direct regulatory role of GATA-factors for Laminin regulation, but in the context of this study, it would be interesting to investigate, which GATA-factor takes over the regulatory role of Srp in vertebrates. Interestingly, the reciprocal loss of GATA4 or GATA6 in epithelium-derived tumor cells reveals a subsequent loss of Laminin expression38. In the context of our results and with the assumption that GATA-factors in vertebrates take over the role of Laminin regulation, it makes sense that epithelial cells show a strong expression of GATA-factors.

A recent study supports this notion, revealing a common role of Srp and human GATA4/6 in epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT)39. Although, functions in epithelial maintenance and EMT seems to contradict each other, Laminin activation is required in mesenchymal cells for the migration-related processes8,40. As the presence of Srp disturbs the epithelial character in Drosophila39,41, we assume that the initial Laminin activation by Srp is essentially required in all Srp-dependent tissues, and that subsequent Laminin regulation for epithelial tissue assembly and maintenance must be ensured by other GATA-factors. Maintenance of gene expression in the differentiated midgut epithelium has already been demonstrated for dGATAe42, along with the fact that amnioserosa differentiation is dependent on dGATAa/pannier43,44.

Material and Methods

Fly stocks and genetics

Flies were grown under standard conditions45 and crosses were performed at 25 °C or 29 °C (for GAL4/UAS experiments). Staging of embryos was done according to46. The following mutations and fly stocks were used in this study: as control or wild-type stocks we employed white1118 or balanced sibling embryos. We use mef2-GAL4 (BDSC 27390), UAS-mCherry.NLS (BDSC 38425), UAS-lacZ (BDSC 1777), srp3 (BDSC 2485), srpneo45 (BDSC 59020), srp::GFP (VDRC 318053) and UAS-srpNC27.

Fluorescence antibody staining

Antibody staining of Drosophila embryos was essentially performed as described in47. The following primary antibodies were used in their specified dilutions: mouse anti-Green fluorescent protein (GFP, 1:250, Roche Diagnostics), rabbit anti-Green fluorescent protein (GFP, 1:500, abcam), guinea-pig anti-β3tubulin (ß3Tub, 1:600048), rabbit anti-LamininB1 (LanB1, 1:40049) and rabbit anti-LamininB2 (LanB2, 1:40049). Alexa Cy-coupled secondary antibodies were purchased from Dianova and Jackson ImmunoResearch, and Hoechst 55380 from Sigma Aldrich. Embryos were embedded in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech) before visualization under Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

Generation of transgenic GFP reporter flies

Genomic DNA from wildtype Drosophila melanogaster was used for PCR amplification of respective sequences (LanB1 IE 5′ forward: CGAGTACGGATTCCCCACTG AAG; LanB1 IE 5′ reverse: CCGGCACTAGAAATGTTCTGAAAC; LanB1 IE 3′ forward: CAGTGGTCAGTCGCGAGGAA LanB1 IE 3′ reverse: CGATAAGCCGCAGCTCCAAC; LanB2 UE forward: CACGGGAAATTAAATGACGCGCCAA; LanB2 UE reverse: AGTGAAACTCTGTACTCTGCGCTCA; LanB2 IE 5′ forward: CGCAAGTACTCCAACCAGATCCGAC; LanB2 IE 5′ reverse: CTGATA CTGGAACTTACACCCCGCG; LanB2 IE 3′ forward: GAATGTGGTGTGTGTATGTGTGCGC; LanB2 IE 3′ reverse: GGTTGTACTTTGGTGTCTCGCTCG). The PCR fragments were sequenced, cloned into pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega) and subcloned into pH-Pelican-GFP vector50. Standard P-element transformation into w1118 embryos was performed by BestGene Inc. and the Renkawitz-Pohl lab.

Bioinformatics

Evolutionary conservation in non-coding regions of LanB1 and LanB2 were identified by using PhastCons datasets of 14 insect species19. The intergenic regions upstream of the first transcription start site and the intronic sequences of LanB1 and LanB2 were analyzed by CIS-BP Database (PWMs log Odds, Threshold: 0.8)18 and JASPAR (Threshold: 0.8)17 for potential TFBSs. Further manually separations were performed according to the conservation score19 in the UCSC genome browser51 using BDGP R5 dm3.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

For preparation of chromatin, crosslinked 0–24 h old embryos (w1118 and srp::GFP) were used. Embryos were collected and dechorionated as described in45. Fixation was performed as previously described52. For sonification embryos were treated with a Branson 250 with four bursts for 30 s and 20–40% power in 3 ml RIPA buffer and 0.5 ml acid-washed glass beads (Sigma, G8772). Chromatin purification was performed as in53. 1 ml chromatin extract were preabsorbed with 20 µl Protein A/G agarose beads (Merck, IP05), while anti-GFP (Abcam, ab290, 1:500) antibody was incubated with 20 µl agarose beads in 1 ml RIPA buffer at 4 °C for one hour with an overhead shaker. The preabsorbed chromatin extract was incubated with the antibody-coupled agarose beads over night at 4 °C with an overhead shaker. DNA was purified with spin columns and used as template for qPCR.

Real-time PCR

ChIP samples and 1% input were used for one 15 µl PCR reaction. Analyses were performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (Biorad). The results were presented as percentage of input of precipitated chromatin. The following primers were used: LanB1-GATA-TFBS1 (forward: ACTCCTTCTCCCTGCCTATTCT, reverse: CGGATGCGAAGGAGTGGAAA); LanB1-GATA-TFBS2 (forward; TTGTGGCACACTGCCTCTTT, revers: GGCATTTGAAGCCCTTGCC); LanB1-Srp-TFBS1 + 2 (forward: AAAACTTGGGTTCTTATCTCACCG, reverse: TTCTTATGAAGATTTCGACGGG); LanB1-GATA-TFBS3 + 4 (forward: ACTGATAAAAACAGCGATCCAACG, reverse: CCGACTACTCTCAATATAAGGTCCC); LanB1-Srp-TFBS3 (forward: TGGTACGAGACGAAAATAAATCGG, reverse: GCTTCTATCATCACTGTAAACCGC); LanB1-control1 (forward: AATCAAGCAAGTGGGAGCGA, reverse: CCAGACTGACCGAGGTGTTC); LanB1-control2 (forward: ATGGCCCAACCCACTTTTCA, reverse: TGCTAATCGCGCACAAACAA); LanB2-Srp-TFBS1 (forward: ATGAAACCGAAAGTGCGGC, reverse: AGCTGGACTCTCTGCTCTACT); LanB2-GATA-TFBS1 (forward: TCGACTTGTTGTTGCTGCCT, reverse: CGGGAAACACTCCGTCACAT); LanB2-TFBS-GATA-TFBS2-Srp-TFBS2 (forward: TTTCGAACCGTAAAGAGCCCA, reverse: AAGTCCTATGTTTATCAATGGCACC); LanB2-control1(forward: TCATTGTGGCGGTTTCCTGT, reverse: GCCTGATCCTTCTTGCTGGT); LanB2-control2 (forward: ATGAATTTGGAAGCGTGGCG, reverse: CGCCTGTAGCCCGGATAAAA).

Statistical analysis

R 3.5.1 was used for statistical analysis54.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC, NIH P40OD018537), Lynn Cooley, Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC, NIH 2P40OD010949-10A1), Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), Marc Haenlin and Christian Klaembt for materials and fly stocks. We are grateful to Sabina Huhn in the Renate Renkawitz-Pohl lab for plasmid injection. We thank Nikola-Michael Prpic-Schaeper for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. A.H.: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/DFG (Ho-2559/5-1).

Author contributions

U.T. Investigation, methodology, conceptualization, visualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing original draft, writing review and editing. M.C.B. Investigation, data curation, conceptualization and visualization. M.B. Supervision. A.H. Investigation, conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, funding acquisition, project administration, writing review and editing.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-52210-9.

References

- 1.Timpl R, Brown JC. Supramolecular assembly of basement membranes. BioEssays. 1996;18:123–132. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell Adh. Migr. 2013;7:56–63. doi: 10.4161/cam.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita A, Sugimoto E, Kitagawa Y. Post-translational assembly and glycosylation of laminin subunits in parietal endoderm-like F9 cells. Biochem. J. 1985;229:259–264. doi: 10.1042/bj2290259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumagai C, Kadowaki T, Kitagawa Y. Disulfide-bonding between Drosophila laminin β and γ chains is essential for α chain to form αβγ trimer. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:211–216. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto A, Aoki M, Ichihara S, Kitagawa Y. α-, β- or γ-chain-specific RNA interference of laminin assembly in Drosophila Kc167 cells. Biochem. J. 2001;360:167–172. doi: 10.1042/bj3600167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters BP, et al. The biosynthesis, processing, and secretion of laminin by human choriocarcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:14732–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbano JM, et al. Drosophila laminins act as key regulators of basement membrane assembly and morphogenesis. Development. 2009;136:4165–4176. doi: 10.1242/dev.044263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfstetter G, Holz A. The role of LamininB2 (LanB2) during mesoderm differentiation in Drosophila. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:267–282. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0652-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollfelder D, Frasch M, Reim I. Distinct functions of the laminin β LN domain and collagen IV during cardiac extracellular matrix formation and stabilization of alary muscle attachments revealed by EMS mutagenesis in Drosophila. BMC Dev. Biol. 2014;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-14-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurchenco PD, et al. The chain of laminin-1 is independently secreted and drives secretion of its - and -chain partners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:10189–10194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petley-Ragan LM, Ardiel EL, Rankin CH, Auld VJ. Accumulation of Laminin Monomers in Drosophila Glia Leads to Glial Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Disrupted Larval Locomotion. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:1151–1164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1797-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domogatskaya A, Rodin S, Tryggvason K. Functional Diversity of Laminins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:523–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuter R. The gene serpent has homeotic properties and specifies endoderm versus ectoderm within the Drosophila gut. Development. 1994;120:1123–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narasimha M, Brown NH. Novel Functions for Integrins in Epithelial Morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montell DJ, Goodman CS. Drosophila substrate adhesion molecule: sequence of laminin B1 chain reveals domains of homology with mouse. Cell. 1988;53:463–73. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montell DJ, Goodman CS. Drosophila laminin: sequence of B2 subunit and expression of all three subunits during embryogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:2441–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan A, et al. JASPAR 2018: Update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles and its web framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D260–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weirauch MT, et al. Determination and Inference of Eukaryotic Transcription Factor Sequence Specificity. Cell. 2014;158:1431–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siepel, A. & Haussler, D. Phylogenetic Hidden Markov Models. In Statistical Methods in Molecular Evolution 325–351, 10.1007/0-387-27733-1_12 (Springer-Verlag, 2005).

- 20.Zhu LJ, et al. FlyFactorSurvey: a database of Drosophila transcription factor binding specificities determined using the bacterial one-hybrid system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D111–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whyatt DJ, deBoer E, Grosveld F. The two zinc finger‐like domains of GATA‐1 have different DNA binding specificities. EMBO J. 1993;12:4993–5005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson CR, Szauter P. Cytogenetic analysis of chromosome region 89A of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation of deficiencies and mapping of Po, Aldox-1 and transposon insertions. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:11–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00286176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abel T, Michelson AM, Maniatis T. A Drosophila GATA family member that binds to Adh regulatory sequences is expressed in the developing fat body. Development. 1993;119:623–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehorn KP, Thelen H, Michelson AM, Reuter R. A molecular aspect of hematopoiesis and endoderm development common to vertebrates and Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:4023–4031. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank LH, Rushlow C. A group of genes required for maintenance of the amnioserosa tissue in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1343 LP–1352. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meister M, Lagueux M. Drosophila blood cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2003;5:573–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waltzer L, Bataillé L, Peyrefitte S, Haenlin M. Two isoforms of serpent containing either one or two GATA zinc fingers have different roles in Drosophila haematopoiesis. EMBO J. 2002;21:5477–5486. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamp J, et al. Drosophila Kette coordinates myoblast junction dissolution and the ratio of Scar-to-WASp during myoblast fusion. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:3426–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.175638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaipa BR, et al. Dock mediates Scar- and WASp-dependent actin polymerization through interaction with cell adhesion molecules in founder cells and fusion-competent myoblasts. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:360–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schäfer G, et al. The Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) is essential for myoblast fusion in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2007;304:664–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger S, et al. WASP and SCAR have distinct roles in activating the Arp2/3 complex during myoblast fusion. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1303–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsubayashi Y, et al. A Moving Source of Matrix Components Is Essential for De Novo Basement Membrane Formation. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:3526–3534.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Sánchez BJ, et al. Drosophila Embryonic Hemocytes Produce Laminins to Strengthen Migratory Response. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarnitzky T, Volk T. Laminin is required for heart, somatic muscles, and gut development in the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 1995;169:609–18. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pevny L, et al. Erythroid differentiation in chimaeric mice blocked by a targeted mutation in the gene for transcription factor GATA-1. Nature. 1991;349:257–260. doi: 10.1038/349257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujikura J, et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells is induced by GATA factors. Genes Dev. 2002;16:784–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.968802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Futaki S, Hayashi Y, Emoto T, Weber CN, Sekiguchi K. Sox7 plays crucial roles in parietal endoderm differentiation in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells through regulating Gata-4 and Gata-6 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10492–503. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10492-10503.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capo-chichi CD, et al. Anomalous expression of epithelial differentiation-determining GATA factors in ovarian tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4967–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell K, Whissell G, Franch-Marro X, Batlle E, Casanova J. Specific GATA Factors Act as Conserved Inducers of an Endodermal-EMT. Dev. Cell. 2011;21:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urbano JM, Domínguez-Giménez P, Estrada B, Martín-Bermudo MD. PS Integrins and Laminins: Key Regulators of Cell Migration during Drosophila Embryogenesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell K, Lebreton G, Franch-Marro X, Casanova J. Differential roles of the Drosophila EMT-inducing transcription factors Snail and Serpent in driving primary tumour growth. PLOS Genet. 2018;14:e1007167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okumura T, Matsumoto A, Tanimura T, Murakami R. An endoderm-specific GATA factor gene, dGATAe, is required for the terminal differentiation of the Drosophila endoderm. Dev. Biol. 2005;278:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winick J, et al. A GATA family transcription factor is expressed along the embryonic dorsoventral axis in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1993;119:1055–65. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heitzler P, Haenlin M, Ramain P, Calleja M, Simpson P. A genetic analysis of pannier, a gene necessary for viability of dorsal tissues and bristle positioning in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;143:1271–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashburner, M. Drosophila. A laboratory handbook. Dros. A Lab. handbook (1989).

- 46.Campos-Ortega José A., Hartenstein Volker. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1997. Stages of Drosophila Embryogenesis; pp. 9–102. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller H.-Arno J. Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2008. Immunolabeling of Embryos; pp. 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leiss D, Gasch A, Mertz R, Renkawitz-Pohl R. β3 tubulin expression characterizes the differentiating mesodermal germ layer during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1988;104:525–531. doi: 10.1242/dev.104.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumagai T, et al. Screening for Drosophila Proteins with Distinct Expression Patterns during Development by use of Monoclonal Antibodies. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;64:24–28. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barolo S, Carver LA, Posakony JW. GFP and beta-galactosidase transformation vectors for promoter/enhancer analysis in Drosophila. Biotechniques. 2000;29:726, 728, 730, 732. doi: 10.2144/00294bm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spivakov M, et al. Analysis of variation at transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila and humans. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R49. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orlando V, Jane EP, Chinwalla V, Harte PJ, Paro R. Binding of trithorax and Polycomb proteins to the bithorax complex: dynamic changes during early Drosophila embryogenesis. EMBO J. 1998;17:5141–50. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orlando V, Strutt H, Paro R. Analysis of Chromatin Structure byin VivoFormaldehyde Cross-Linking. Methods. 1997;11:205–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available at, https://www.r-project.org/ (Accessed: 29th November 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.